XII. The Battle of the Somme

From September 15 to the Battle of the Ancre

Capture of Eaucourt—Varying character of German resistance—Hard trench fighting along the line—Dreadful climatic conditions—The meteorological trenches—Hazy Trench —Zenith Trench—General observations—General von Arnim’s report

Having described the Battle of Flers, which began upon September 15 and which extended over one, two, or three days according to the completeness of the local victory, or the difficulty of reaching any definite limit, we will now turn once more to the left of the line (always excepting Gough’s flanking army, which has been treated elsewhere), and we shall follow the deeds of the successive divisions in each sector up to the end of the operations. We will begin with the Third Corps, who abutted upon the Canadians in the Martinpuich sector, and covered the line up to Drop Alley, north-east of High Wood, where they joined up with the Fifteenth Corps.

The line on this western section was less active than on the right, where the great villages of Combles, Lesboeufs, and Morval were obvious marks for the advance. After the battle of September 15, the Twenty-third Division, relieving the Fifteenth, took its station at the extreme left of the line, just north of Martinpuich. To the right of the Twenty-third, occupying the Starfish and Prue system of trenches,

On their right was the First, who had relieved the Forty-seventh Division, the victors of High Wood, these three divisions, Twenty-third, Fiftieth, and First, now formed the Third Corps. Their fighting patrols were thrown well out during the days after the battle, and their front posts were as far north as Crescent Alley and Hook Trench. The general attack of September 25, which amounted to a considerable battle, did not seriously affect this portion of the line. The only operation of note before the^end of the month was an attack upon a farm in the front of their line by the 70th Brigade of the Twenty-third Division—a brigade which had greatly distinguished itself during the time it had fought with the Eighth Division upon July 1. This attack failed the first time, but it was repeated with success at dawn upon September 29, and the line moved forward to that limited extent. Another small advance was made by the First Division on the night of September 25, east of Eaucourt, when a piece of trench was carried by the gallantry of a platoon of the 2nd Rifles, consisting almost entirely of Rhodesian volunteers, samples of those wandering Britons who have played a part in this War which can never be chronicled. The way in which the distant sons, prodigal or otherwise, came back to the help of their hard-pressed mother is one of the most beautiful chapters in the history of the Empire.

The Flers front-line trench bends away from the British position as it trends towards the north-west, so that although it had been made good over a large portion in the Battle of Flers, it was still intact opposite the Third Corps. Upon October 1, however, it was attacked, and was taken without any great difficulty, though the Fiftieth in the centre had to fight hard for their section. The storming battalions, after re-forming, continued their advance, and occupied the line between Le Sars and Flers. The village of Eaucourt lay in their path, and was well guarded upon the west by uncut wire, but a tank rolled its majestic path across it and the shouting infantry crowded close behind. The 141st Brigade of the Forty-seventh Division, which had come back once again into the line, was the first to enter this village, which was the sixteenth torn by the British from the grip of the invaders since the breaking of the line, while the French captures stood at an even higher figure. There was a strong counter-attack upon Eaucourt during the night, accompanied by a shortage of bombs owing to the fact that the store had been destroyed by an unlucky shell. The Germans for the time regained the village, and the ruins were partly occupied by both armies until October 3, when the British line, once more gathering volume and momentum, rolled over it for the last time. It had been stoutly defended by men of a German reserve division, and its capture had cost us dear. One of the mysteries of the fighting at this stage was the very varied quality of the resistance, so that the advancing British were never sure whether they would find themselves faced by demoralised poltroons, capable of throwing up their hands by the hundred, or by splendid infantry, who would fight to the death with the courage of despair.

Having won Eaucourt, the next village which, faced the British line in this sector was Le Sars, immediately to the north-west. The advance upon this was carried out amid rain and slush which made military operations almost impossible. It was again found that the resistance was very spirited, but the place was none the less carried and consolidated upon October 7.

In the week preceding the final assault there was hard fighting, during which the 70th Brigade won its way forward into a favourable position for the attack. The 8th York and Lancasters particularly distinguished themselves by their gallantry in clearing by bombing the outlying German defences. Major Sawyer and Lieutenant de Burgh of that battalion winning the Cross for their fine leadership upon that occasion. The decisive attack was carried out by the other two brigades of the Twenty-third Division, which advanced upon the village, whilst the Forty-seventh Division made an attempt upon the formidable Butte of Warlencourt. The latter venture met with no success, but the former was brilliantly carried out. The advance was made by the 68th Brigade upon the right and the 69th upon the left, the Martinpuich-Warlencourt road being the dividing line between the two divisions. The attack was at 1:45 P.M., and in broad daylight the battalions concerned, notably the 12th and 13th Durhams and the 9th Yorks, clambered over their sodden sandbags and waded through the mud which separated them from the Germans. The numbers were so reduced that the companies formed only two weak platoons, but none the less they advanced very steadily. Captain Blake, leading the first company of Durhams, was shot dead; but another captain took over both companies and led them straight at the village, both the 12th Durhams and 9th Yorks reaching the sunken road in front of the houses at about the same moment. They worked their way down this and bombed many Germans in their dug-outs. Here, as elsewhere, experience proved that this system of taking refuge from shell-fire in deep burrows has very serious military disadvantages, not merely on account of the difficulty of getting out, but from the more serious objection that the men, being trained to avoid danger, continued to shrink from it when it was essential that they should rush out and face it. The yellow faces and flaccid appearance of our prisoners showed also the physical results of a troglodytic life.

A single tank which had accompanied the advance was set on fire by a shell, but the infantry pressed on undismayed, and well backed up by the 10th and 11th Northumberland Fusiliers and 8th Seaforths, they soon seized the whole village and firmly consolidated their position. The success was partly due to the fine handling of machine-guns, which turned the favourite weapon of the Germans against themselves. Five of these guns, 8 officers, and 450 men were taken during the operation.

The Forty-seventh Division, meanwhile, in attempting to make similar progress upon the right was held up by very heavy rifle and machine-gun fire. Immediately afterwards, this division, much worn by its splendid service, was taken out of the line, being replaced by the Ninth Scottish Division. Their companion Division, the Fifteenth, had come back upon their left. The weather now became so abominable and the mud so abysmal, that all prospect of farther progress in this section had to be abandoned.

The old prehistoric mark called the Butte of Warlencourt, which had long stood up as a goal in front of the British trenches, proved really to be the final mark of the advance until a new season should dawn.

Upon October 12 there was an attempt to get forward, but the conditions were impossible, and the results unsatisfactory. In this affair the gallant Ninth Division had considerable losses, their advance being conducted with the 26th Brigade upon the right and the South Africans upon the left. Some small gain was achieved by the former, but the latter were held up by a deadly machine-gun fire. The Thirtieth Division was upon the right of the Ninth at this period, and twice endeavoured to get forwards—once upon the 12th and once upon the 18th; but neither of these attempts had good success, partly owing to the very bad weather, and partly to the excellent resistance of the Sixth Bavarian Reserve Division, which is described by those who have fought against it as one of the very best divisions in the German army. On the 20th a fresh attack was made by the 27th Brigade with no success and heavy losses to the 6th Scottish Borderers. Early in November a renewed attempt was made by the Fiftieth Division to advance in this quarter, but the country was a morass and no progress was possible. The Canadians, Forty-eighth and Fiftieth Divisions, who held the Le Sars front, were condemned to inactivity. From that time onwards the line of the Third Corps was undisturbed, save for a strong counter-attack upon November 6, which neutralised a small advance made upon the 5th. Le Sars and Eaucourt were consolidated and continued to be the British advanced posts in this quarter. The conditions of mud and discomfort can only be described as appalling.

Having briefly traced the work of the Third Corps The from the action of September 15 to the coming of the of the winter, we shall now turn to the Fifteenth Corps upon the right and follow their operations from the same date. It will be remembered that the New Zealanders formed the left-hand division, and that they had advanced so finely that by the evening of September 16 they were up to, but not in, Goose Alley and Factory Corner, from which the) were within striking distance of the Gird System.

Before attacking this, however, it was necessary to get a firmer hold of Flers Trench, which in its western reaches was still in the hands of the Germans. It was a desperate business of bombing from traverse to traverse and overcoming successive barricades upon a very narrow front where a few determined men could hold up a company. This difficult business was taken in hand at 8:30 on the night of September 21 by the 2nd Canterbury Battalion, who advanced down the trench. It was a Homeric conflict, which lasted for the whole night, where men stood up to each other at close quarters, clearing away the dead and dying in order to make room for fresh combatants in the front line. Down Flers Trench and Drop Alley raged the long struggle, with crash and flare of bombs, snarl of machine-guns, shrill whistles from rallying officers, and shouts from the furious men. The New Zealand Black Watch had gained a portion of the trench, but the German reinforcements streamed down a communication trench which opened behind them, and found themselves between the two bodies of New Zealanders. It was a great fight, but by morning it had been definitely decided in favour of the men from oversea. The long section of Flers Trench was cleared and part of Goose Alley, opening out of it, was held. No less than 350 German dead were picked up, and a handful of prisoners were left with the victors. The New Zealand losses were about 150 of all ranks.

On September 25 the New Zealanders tightened their grip upon Goose Alley, which connects up the Flers and the Gird Systems of trenches. In the meantime the divisions upon their right were moving to the north-east of Flers towards the village of Guedecourt, which lay upon the farther side of the Gird Trenches. The actual attack upon the village was committed to the Twenty-first Division, who advanced on a two-brigade front, the 110th Leicester Brigade making straight for the village itself, while the 64th Brigade upon its right, strengthened by the inclusion of the 1st Lincolns, was ordered to occupy 1000 yards of front to the right. The two brigades were not equally fortunate. The Leicester brigade, by a fine advance, pierced the Gird Trench, and made their way beyond it. The 64th Brigade was held up by uncut wire, which they could not penetrate. The result was that the Leicesters, being heavily counter-attacked, and having their flanks open, were forced back as far as the Gird Trench, to which they clung. The position in the evening was a curious one, for we held the Gird Trench at two different points, but between them lay a stretch of 1000 yards still occupied by the Germans and faced with uncut wire. Orders reached the Divisional General during the night that at all costs the position must be carried. By a happy inspiration he sent for a tank from Flers, and ordered the Leicesters to bomb down Gird Trench in co-operation with the tank, which crawled along parapet. A strong point had been erected at the far end of the trench, and the Germans as they rushed away from the danger ran into a deadly machine-gun fire. The upshot was that a great number were killed, while 8 officers and 362 men were taken, with a loss to the attackers of 5 wounded. To add to the quaintness of the operation, an aeroplane flew low over the trench during its progress, helping with its bombs to make the victory complete. The result was far more than the capture of the trench, for the 64th Brigade, led by the Durhams, at once swept forward and captured their objective, while the 110th Brigade upon the left reached Guedecourt under happier auspices and remained in possession of the village.

Although the Gird line had been pierced at this point, it was held in its western length, and this was attacked upon September 27 by the New Zealanders and the Fifty-fifth Lancashire Territorial Division, both of which gained their objectives, so that the whole end of this great trench system from a point north of Flers passed definitely into the British possession.

On October 1 there was a fresh general advance which led to no great change in this part of the line, save that both the New Zealanders and the Twenty-first Division improved their position, the latter getting as far as Bayonet Trench. Shortly afterwards the New Zealanders were drawn out, having been 23 consecutive days in the line, and earned themselves a great reputation. “The division has won universal confidence and admiration,” said Sir Douglas Haig. “No praise can be too high for such troops.”

We now turn to the Fourteenth Corps, which filled the remainder of the British line up to the point of its junction with the French. During the battle the division of Guards had, as will be remembered, held the left of this line, but on the day after it was replaced for a short time by the Twentieth Division, whose 61st Brigade, especially the 7th Cornwalls and 12th King’s, were heavily engaged. The 60th Brigade had pushed up into the fighting line, and received a strong German counter-attack in the morning of the 17th, which broke down before the rifles of the 6th Shropshire Light Infantry. In the afternoon the 59th Brigade advanced upon the left and the 60th upon the right, closing in upon the Morval position. The 12th King’s Royal Rifles of the latter brigade was held up by a strong point and lost heavily, but the general effect was to bring the British line nearer to the doomed village. Twice upon the 18th, German counter-attacks swarmed down upon the exposed right flank of the 60th Brigade, but each time they were blown back by the fire of the 12th Rifle Brigade and the 12th Rifles. The 59th Brigade had made no progress, the two Rifle Brigade battalions (10th and 11th) having particularly heavy losses upon the 17th, but they were holding their line strongly. It was impossible to do more for the moment, for the Sixth Division upon their right was still hung up, as already described, by the Quadrilateral. Shortly after that obstacle had been overcome, the Guards took over once more from the Twentieth, and were ready in conjunction with the Sixth and Fifth Divisions for a serious advance upon Morval and Lesboeufs.

On September 22 the 3rd Guards Brigade was in touch with the Twenty-first Division upon the left, which was now holding Gird Trench and Gird Support as far north as Watling Street. On this day the 4th Grenadiers, reverting after centuries to the weapon which their name implies, were bombing their way up Gas Alley, which leads towards Lesboeufs. On the 23rd the Twenty-first on the left, the Guards in the centre, and the Sixth Division were advancing and steadily gaining ground to the north-east, capturing Needle Trench, which is an off-shoot from the Gird System. On the 24th the Germans counter-attacked upon the 16th Brigade, the blow falling upon the 1st Buffs, who lost four bays of their trench for a short period, but speedily drove the intruders out once more. The 14th Durham Light Infantry also drove off an attack. The Fifth Division was now coming up on the right of the Sixth, and played a considerable part in the decisive attack upon September 25.

On this date an advance of the four divisions on this section of the line carried all before it, the Twenty-first being north of Delville Wood, the 3rd Brigade of the Guards operating on the German trenches between Guedecourt and Lesboeufs, the 1st Brigade of Guards upon the left of the village of Lesboeufs, the Sixth Division upon the right of Lesboeufs, and the Fifth Division on Morval.

In this attack the 4th Grenadiers upon the extreme left of the Guards were badly punished, for the Twenty-first upon their left had been held up, but the rest came along well, the 1st Welsh forming a defensive flank upon the left while the other battalions reached their full objective and dug in, unmolested save by our own barrage. The 1st Irish and 3rd Coldstream, who were on the left of the 1st Brigade, also got through without heavy loss and occupied the trenches to the immediate north and north-east of Lesboeufs.

The 2nd Grenadiers, who led the right of the Brigade, with their supporting battalion the 2nd Coldstream, headed straight for the village, and were held up for a time by uncut wire, but the general attack upon the right was progressing at a rate which soon took the pressure off them.

The British infantry were swarming round Lesboeufs in the early afternoon, and about 3:15 the 1st West Yorks of the 18th Brigade penetrated into it, establishing touch with the Guards upon their left. They were closely followed by their old battle companions, the 2nd Durham Light Infantry. The German resistance was weaker than usual, and the casualties were not severe. On the Morval front the 15th Brigade of the Fifth Division, with the 95th Brigade upon their right, were making a steady and irresistible advance upon Morval. The 1st Norfolks and 1st Cheshires were in the front, and the latter battalion was the first to break into the village with the 1st Bedfords, 2nd Scots Borderers, and 16th Royal Welsh Fusiliers in close support. The 1st Cheshires particularly distinguished itself; and it was in this action that Private Jones performed his almost incredible feat of capturing single-handed and bringing in four officers and 102 men of the 146th Würtemberg Regiment, including four wearers of the famous Iron Cross. The details of this extraordinary affair, where one determined and heavily-armed man terrorised a large company taken at a disadvantage, read more like the romantic exploit of some Western desperado who cries “Hands up!” to a drove of tourists, than any operation of war. Jones was awarded the V.C, and it can have been seldom won in such sensational fashion.

Whilst the 15th Brigade of the Fifth Division attacked the village of Morval the 95th Brigade of the same division carried the German trenches to the west of it. This dashing piece of work was accomplished by the 1st Devons and the 1st East Surreys. When they had reached their objective, the 12th Gloucesters were sent through them to occupy and consolidate the south side of the village. This they carried out with a loss of 80 men. In the evening a company of the 6th Argylls, together with the 2nd Home Company Royal Engineers, pushed on past the village and made a strong point against the expected counter-attack; while the 15th Brigade extended and got into touch with the 2nd York and Lancasters of the Sixth Division upon their left. It was a great day of complete victory with no regrets to cloud it, for the prisoners were many, the casualties were comparatively few, and two more village sites were included by one forward spring within the British area. The Town Major of Morval stood by his charge to the last and formed one of the trophies. On the 26th the Germans came back upon the Guards at about one o’clock, but their effort was a fiasco, for the advancing lines came under the concentrated fire of six batteries of the 7th Divisional Artillery. Seldom have Germans stampeded more thoroughly. “Hundreds of the enemy can be seen retiring in disorder over the whole front. They are rushing towards Beaulencourt in the wildest disorder.” Such was the report from a forward observer. At the same time a tank cleared the obstacles in front of the Twenty-first Division and the whole line was straight again. The British consolidated their positions firmly, for it was already evident that they were likely to be permanent ones. The Guards and Fifth Division were taken out of the line shortly afterwards, the Twentieth Division coming in once more upon September 26, while upon September 27 the French took over part of the line, pushing the Twentieth Division to the left, where they took over the ground formerly held by the Twenty-first. Upon October 1 the 61st Brigade was ordered to push forward advanced posts and occupy a line preparatory to future operations. This was well carried out and proved of great importance when a week later attacks were made upon Cloudy and Rainbow Trenches.

Leaving this victorious section of the line for the moment, we must turn our attention to the hardworked and splendid Fifty-sixth Division upon their right, whose operations were really more connected with those of the French on their right than with their comrades of the Fourteenth Corps upon the left. By a happy chance it was the French division of the same number with which they were associated during much of the time. It will be remembered that at the close of the Flers action (September 15 and on), the Fifty-sixth Division was holding a defensive flank to the south, in the region of Bouleaux Wood, part of which was still held by the Germans. They were also closing in to the southwards, so as to co-operate with the French, who were approaching Combles from the other side. On September 25, while the Fifth were advancing upon Morval, the Fifty-sixth played an important part, for the 168th, their left brigade, carried the remainder of Bouleaux Wood, and so screened the flank of the Fifth Division. One hundred men and four machine-guns were captured in this movement. On the 26th, as the woods were at last clear, the division turned all its attention to Combles, and at 3:15 in the afternoon of that day fighting patrols of the 169th Brigade met patrols of the French in the central square of the town. The Germans had cleverly evacuated it, and the booty was far less than had been hoped for, but none the less its capture was of great importance, for it was the largest place that had yet been wrenched out of the iron grasp of Germany. After the fall of Combles the French, as already stated, threw out their left wing upon that side so as to take over the ground which had been covered by the Fifty-sixth Division, and afterwards by the Fifth Division.

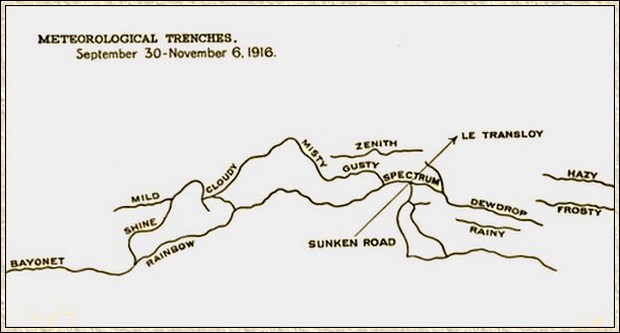

On September 30 the Fifty-sixth Division took over from the Guards, and again found itself upon the right of the British line, and in touch w4th the new dispositions of the French. On its left was the Twentieth Division, and on their left the Sixth. These three divisions now found themselves opposite to a long line of trenches, to which various meteorological names had been given, though the actual meteorological conditions at the time formed a greater obstacle than the defences in front of them. A simple diagram will show more clearly than any words how these formidable trenches lay with regard to the British advance.

Meteorological Trenches, September 30-November 6, 1916

It may well seem to the reader that the defenders are bound to have the best of the argument when they can thus exchange one line for another, and as quickly as they are beaten out of one set of strongholds confront their enemy with another one. No doubt so long as the lines are stoutly held this is true as regards the rate of advance. But as far as it concerns the losses which mark that vital attrition which was wearing Germany to the bone it was very different, These trenches were not like the old permanent fortifications where German officers in a 30-foot dug-out could smile over the caricatures in Ulk and smoke an indolent cigarette, while the impotent British shells pitted the earth-surface far above them. There was no such shelter in these hastily-constructed burrows, while the guns which raked and pounded them grew stronger and more numerous from day to day. Let the machine-gun do its worst, the heavy gun is still the master of the field, for the machine-gun can only levy its toll when circumstances favour it, while day or night the heavy gun is a constant dread. We have had to mourn the swathes of our dead in the open, but the Germans lay as thick amid the clay and chalk of the Picardy ditches. With fine manhood they clung to them and beat back our infantry where they could, but the tales of deserters, the letters found on the wounded, and the condition of the trenches when taken, all told the same story of terrible loss.

On October 7 there was an infantry attack upon this trench system in which the Forty-first, Twelfth, Twentieth, and Fifty-sixth Divisions, together with the French, all took part in the order named from the left. The weather was most execrable, and its vileness told entirely against the Allies, since it was they who had to move, and since the superior gun-power needed for a modern attack was largely neutralised by the difficulty in using aircraft observation. The attack was at 1:45 P.M., when the troops advanced under a heavy barrage along the whole sodden and slippery front. The results were unequal, though the infantry behaved everywhere with their wonted valour and perseverance.

The 122nd Brigade upon the extreme left of the attack could only get on about a hundred yards, so heavy was the fire; while the 124th to the right of them could do little better, and eventually dug in at a point 200 yards short of the Bayonet Trench, which was their immediate objective. Seventy officers and nearly 1300 men fell during this attack of the Forty-first Division, which was handicapped in many ways, for the men were weary, it was too cloudy for reconnaissance, the battalions were already depleted, and the enemy was fresh and unshaken. The success of the Twelfth Division upon the right of the Forty-first was little better. The 36th and 37th Brigades endured heavy losses, especially in the case of the two Royal Fusilier battalions and of the 6th Buffs, whose colonel greatly distinguished himself. In spite of every effort and considerable loss there were no permanent gains of importance at this point.

Things went better, however, with the Twentieth Division upon the right. The two brigades in the front line were the 61st upon the left and the 60th on the right. The leading battalions, counting from the left, were the 7th Yorks Light Infantry, 12th King’s Liverpool, 6th Oxford and Bucks, and 12th Rifle Brigade. The troops had to endure a considerable shelling before leaving their trenches, but it seemed only to add additional fire to their advance, which swept over the low ridge in front of them, and took a long stretch of Rainbow Trench. The right attack was slower than the left, as it ran into a dip of the ground in which the Germans had some cleverly-sited wire entanglement, unseen and untouched by our guns. Nothing daunted, the Oxford and Bucks proceeded to cut lanes through the wire under heavy fire, and one officer of the battalion had actually succeeded in crawling under it when he was shot at point-blank range from the German trench. The front line had now done its work and rested in Rainbow, while the second line — consisting, from the left, of the 7th Somersets, 7th Cornwalls, 6th Shropshires, and 12th Rifles—swept onwards in splendid form, capturing both Cloudy and Misty Trenches. There the victorious infantry dug themselves in on the forward slope of the ridge. The brigades were ahead of their comrades, with the result that their flanks were exposed, they suffered from enfilade fire, and it was necessary to form defensive flanks. Two counter attacks were made during the day, but both were beaten of!. The prisoners captured in this fine advance were 5 officers and 187 men, with 5 machine guns and 2 trench-mortars. By the morning of the 8th strong points had been made and the whole line was defiant of recapture.

The Fifty-sixth Division had advanced with equal valour upon the right and had made good progress, though its gains had not been so substantial as those of the Twentieth. The 167th Brigade had attacked upon the left and the 168th upon the right. They ended with the 7th Middlesex, their flank battalion upon the left in touch with the Twentieth . Division in Rainbow, while the London Scots on the extreme right were in touch with the French in Hazy Trench. The fighting was bitter, however, the men wearied, and the conditions abominable. All the battalions lost heavily, the 4th London being the chief sufferer, for it was on the left flank of the 168th Brigade and was held up by a particularly murderous machine-gun. In the evening a strong German counter-attack, rushing in upon Hazy Trench behind a thick shower of bombs, drove back both the 168th Brigade and the French to their own original line. For the time the advance had failed upon the right.

The 167th Brigade had held on to Rainbow and were now bombing their way down Spectrum. They held their ground there during the night, and on October 8 were still advancing, though the 3rd London coming up to reinforce ran into a heavy barrage and were sadly cut up. The British barrage was found to be practically useless because the guns had been brought up too near. The 169th Brigade had come up on the right and was hotly engaged, the London Rifle Brigade getting up close to Hazy and digging in parallel to it, with their left in touch with the Victorias. The Germans, however, were still holding Hazy, nor could it be said in the evening that the British were holding either of the more advanced trenches, Dewdrop or Rainy. In the evening the London Rifle Brigade were forced to leave their new trench because it was enfiladed from Hazy, and to make their way back to their old departure trenches as best they could, dragging with them a captured machine-gun as a souvenir of a long and bloody day’s work. On October 9 the British held none of the points in dispute in this section on the right, save only a portion of Spectrum. There was a pause in this long and desperate fight which was conducted by tired infantry fighting in front of tired guns, and which left the survivors of both sides plastered with mud from head to heel. When it was resumed, the two British divisions, the Twentieth and Fifty-sixth, which had done such long service in the line, and were greatly reduced, had been withdrawn. The Fourth Division had taken the place of the Londoners, while the Sixth, itself very worn, had relieved the Twentieth.

On October 12 both these divisions delivered an attack together with the French and with the Fifteenth Corps upon their left. The 14th Durham Light Infantry were in Rainbow on the left and were in touch with the 1st West Yorks of the 18th Brigade upon their right, but could find no one upon their left, while the German pressure was very strong. The 18th Brigade worked along Rainbow, therefore, until it got into touch with the Twelfth Division upon their left. The Twelfth Division had been lent the 88th Brigade of the Twenty-ninth Division, and this gallant body, so terribly cut up on July 1, had an instalment of revenge. They won their objective, and it is pleasant to add that the Newfoundlanders especially distinguished themselves. The 16th Brigade upon the right attacked Zenith Trench, the 2nd York and Lancaster leading the rush. The position could not be held, however, by battalions which were depleted by weeks of constant strain and loss. A report from a company officer says: “The few unwounded sheltered in trench holes and returned in the dusk. The fire was too strong to allow them to dig in. The Brigade line is therefore the same as before the attack.”

Whilst the Sixth Division had been making this difficult and fruitless attack the Fourth Division upon their right had been equally heavily engaged in this horrible maze of mud-sodden trenches, without obtaining any more favourable result. The 12th Brigade fought on the immediate right of the 16th, some of them reaching Spectrum, and some of them Zenith. The 2nd West Ridings and 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers were the heaviest sufferers, the latter holding a line of shell-holes in front of Spectrum where they were exposed to a terrible barrage. The 10th Brigade were on their right, and one battalion, the 1st Warwick, reached Foggy, but was unable to hold it under the crushing fire. By the evening of October 13, however, the whole of Spectrum had at last been seized, and the enemy, who attempted to bomb along it from Dewdrop, were repulsed. On October 18, the 88th Brigade again had a success, the 2nd Hants and 4th Worcesters doing particularly well. For a time the fighting died down, the British licking their wounds and sharpening their claws for a fresh grapple with these redoubtable trenches.

This came upon October 23, when there was an advance at 2:45 in the afternoon by the Fourth Division upon the right and the Eighth Division upon the left. The three-brigade front covered by the Eighth Division is indicated by the fact that the 2nd East Lancashires, the left battalion of the left brigade (24th), was directed upon the junction between Mild and Cloudy, while the right brigade (23rd) had Zenith for its objective. The first attack of the left brigade failed, but the second brought them into Cloudy. By 4:15 the 2nd Scots Rifles of the 23rd Brigade had penetrated the right of Zenith, and some small parties had even moved on to Orion beyond. The central brigade (25th) had won its way up to Misty, the 2nd Lincolns, 2nd Berks, and 2nd Rifle Brigade in the lead. In the meantime the East Lancashires on the left were endeavouring to bomb their way down the maze of trenches, filled with yard-deep mud, which separated them from their comrades. The fighting was desperate, however, and the losses considerable. The 2nd Lin coins had got detached in the labyrinth, and were out of touch with their companions. At 6:45 the Germans came again in strength and those of the Scots Rifles who had gained Orion were driven back. The casualties in this splendid battalion, which had suffered so often and so much, were once again very severe.

The Fourth Division had also had a hard fight upon the right and had made no great progress. The French upon their right had been held up after an initial advance. The 12th Brigade attacked Dewdrop, but were unable to hold it. The 11th had seized Hazy, but their grip of it was still precarious. Every position was raked with machine-guns and clogged with the all-pervading and often impassable morass. In mud and blood and driving rain, amid dirt and death, through day and night, the long death-grapple never ceased until exhaustion and winter brought a short surcease.

Upon the 24th the hard-earned gains in these trenches were consolidated. In the sector of the Eighth Division they were substantial and justified the hope that this obdurate line would go the way of all the others which had barred the army. Had it been earlier in the season it would have been easy to wait for clear weather, beat them into pulp with heavy guns, and then under a good barrage capture them by assault. But this could not be done, for Sir Douglas Haig could not afford to wait, with winter coming on and only a few weeks or days left in which to bring his men forward to their final line. The general position upon October 24 was that the 2nd Middlesex of the 24th Brigade held Zenith in part, that the 25th Brigade was in Gusty and held part of Misty, while the 23rd Brigade had made no advance upon the right but their left was in Cloudy and Mild.

Upon this date the Thirty-third Division came up to relieve the Fourth, and upon September 28 it made a brilliant advance which altered the whole situation in this section. At 7 A.M. on that date the 4th King’s Liverpool of the 98th Brigade by a sudden dash carried the whole of Dewdrop, taking 100 prisoners. The 19th Brigade upon the right kept up with the advance, and before evening Frosty, Gunpits, and Dewdrop had all been included in the British line. There was a pause after this advance, and then upon November 5 there was another advance of the Thirty-third, together with the French. Again there was a good gain, which was effected by the 100th Brigade on the right, and the 19th upon the left. Mirage, Boritzka, and Hazy were all reported as being at last in our hands. The 5th Scottish Rifles, 16th King’s Royal Rifles, and 20th Fusiliers all distinguished themselves, and all —especially the last-named—met with considerable losses in this attack. The Seventeenth Division, which had for a few days taken the place of the Eighth, joined in this advance and extended the ground upon their front, the fighting falling chiefly to the 50th Brigade, in which the 7th York and 7th East York were the principal sufferers. Great work was also done by the 51st Brigade, the 7th Borders and the 7th Lincolns particularly distinguishing themselves. These battalions not only cleared up Zenith Trench, but upon the Germans countering they reserved their fire until the stormers were within 40 yards of them, and then mowed down several hundreds of them, “The men marched back seven miles last night,” wrote one of the officers, “after fighting for forty-eight hours without sleep, singing at the tops of their voices all the way. Priceless fellows!”

On November 7 the Eighth Division was at work again, taking 1100 yards of front, 5 machine-guns, and 80 prisoners. The season was now far advanced and prematurely wet and cold, so that winter lines were formed by the British in this quarter with the village of Le Transloy in their immediate front. Over the rest of the line facing north there had been no serious attempt at advance during this period, and the only fighting to be recorded was on the part of the Anzac Corps, who came in at the end of October, and took over the whole front of the Fifteenth Corps in the centre of the line. These troops joined the attack already recorded upon November 5, and captured that portion of Gird Support Trench which was not yet in our possession. For a time they held Bayonet Trench, but were driven out by a strong bombing attack by the 5th Regiment of the Fourth Prussian Guards Division. The Australians and the 50th Brigade worked in close co-operation during these hard days, and it is pleasing to find the high opinion which they entertained of each other, “On several occasions,” says an Australian, “we had to rely on Yorkshire grit to support our division at critical moments, and the Tikes never failed us once. We owe a big debt to the East Yorkshires in particular. We found them the most loyal of comrades.” This sentiment was heartily reciprocated by the Imperial troops.

The fighting now died down in this quarter and the winter lull had set in, leaving the front British trenches some hundreds of yards from Le Transloy and the Bapaume road. It would be an ungenerous of the Briton who would not admit that in holding us off from it so long, even if we make every allowance for the weather and its disastrous consequences to the attack, the Germans performed a fine feat of arms. It was done by fresh units which had not suffered from the gruelling which their comrades had received upon the Somme, and which would no doubt have been worn down in time, as the others had been, but they fought with great tenacity and certainly prevented our winter line from being as far forward as we had hoped.

Whilst giving the German army every credit for its tenacious resistance and for the hard digging by which it constructed so many lines of defence that five months of hard fighting and a dozen separate victories had been unable to carry the attackers through them, we must still insist upon the stupendous achievement of the British. Nearly every division had passed through the fiery ordeal of the Somme, many of them twice and thrice, and each had retired with fresh honour and new records of victory. Apart from great days of battle like July 1, July 14, September 15, and September 26, when many miles of German trench were carried with a corresponding number of prisoners and guns, there was a separate epic round each village and wood, so that the names of many of them will find immortality in military history. High Wood, Trones Wood, Mametz Wood, and Deville Wood each represents a very terrible local battle. So, too, do such village names as Ovillers, Contalmaison, Pozières, Thiepval, Longueval, Ginchy, and especially Guillemont. Every one of these stern contests ended with the British infantry in its objective, and in no single case were they ever driven out again.

So much for the tactical results of the actions. As to the strategic effect, that was only clearly seen when the threat of renewed operations in the spring caused the German army to abandon all the positions which the Somme advance had made untenable, and to fall back upon a new line many miles to the rear. The Battle of the Marne was the turning-point of the first great German levy, the Battle of the Somme that of the second. In each case the retirement was only partial, but each clearly marked a fresh step in the struggle, upward for the Allies, downward for the Central Powers.

In the credit for this result the first place must be given to the efficiency of British leadership, which was admirable in its perseverance and in its general conception, but had, it must be admitted, not yet attained that skill in the avoidance of losses which was gradually taught by our terrible experiences and made possible by our growing strength in artillery. The severe preliminary bombardment controlled by the direct observation which is only possible after air supremacy has been attained, the counter-battery work to reduce the enemy’s fire, the creeping barrage to cover the infantry, the discipline and courage which enable infantry to advance with shrapnel upon their very toes, the use of smoke clouds against flank fire, the swift advance of the barrage when a trench has fallen so as to head off fugitives and stifle the counterattack, all these devices were constantly improving with practice, until in the arts of attack the British Army stood ahead even of their comrades of France. An intercepted communication in the shape of a report from General von Arnim, commanding the Fourth German Army, giving his experience of the prolonged battle, speaks of British military efficiency in every arm in a manner which must have surprised the General Staff if they were really of opinion that General Haig’s army was capable of defence but not of attack. This report, with its account of the dash and tenacity of the British infantry and of the efficiency of its munitions, is as handsome a testimonial as one adversary ever paid to another, and might be called magnanimous were it not that it was meant for no eye save that of his superiors.

But all our leadership would have been vain had it not been supported by the high efficiency of every branch of the services, and by the general excellence of the materiel. As to the actual value of the troops, it can only be said with the most absolute truth that the infantry, artillery, and sappers all lived up to the highest traditions of the Old Army, and that the Flying Corps set up a fresh record of tradition, which their successors may emulate but can never surpass. The materiel was, perhaps, the greatest surprise both to friend and foe. We are accustomed in British history to find the soldier retrieving by his stubborn valour the difficulties caused by the sluggish methods of those who should supply his needs. Thanks to the labours of the Ministry of Munitions, of Sir William Robertson, and of countless devoted workers of both sexes, toiling with brain and with hand, this was no longer so. That great German army which two years before held every possible advantage that its prolonged preparation and busy factories could give it, had now, as General von Arnim’s report admits, fallen into the inferior place. It was a magnificent achievement upon which the British nation may well pride itself, if one may ever pride oneself on anything in a drama so mighty that human powers seem but the instruments of the huge contending spiritual forces behind them. The fact remains that after two years of national effort the British artillery was undoubtedly superior to that of the Germans, the British Stokes trench-mortars and light Lewis machine-guns were the best in Europe, the British aeroplanes were unsurpassed, the British Mills bomb was superior to any other, and the British tanks were an entirely new departure in the art of War. It was the British brain as well as the British heart and arm which was fashioning the future history of mankind.