VIII. The Third Battle of Ypres

September 6 to October 3, 1917

Engagement of Plumer’s Second Army—Attack of September 20— Fine advance of Fifty-fifth Division—Advance of the Ninth Division— Of the Australians—Strong counter-attack upon the Thirty-third Division—Renewed advance on September 20 —Continued rain—Desperate fighting

The attack of August 16, with its varying and not wholly satisfactory results, had been carried out entirely by the armies of Antoine and of Gough. It was clear now to Sir Douglas Haig that the resistance of the Germans was most formidable along the line of the Menin road, where the long upward slope and the shattered groves which crowned it made an ideal position for defence. To overcome this obstacle a new force was needed, and accordingly the Second Army was closed up to the north, and the command in this portion of the field was handed over to General Plumer. This little white-haired leader with his silky manner, his eye-glass, and his grim, inflexible resolution^ had always won the confidence of his soldiers, but the complete victory of Messines, with the restraint which had prevented any aftermath of loss, had confirmed the whole army in its high appreciation of his powers.

These changes in the line, together with the continued rain, which went from bad to worse, had the effect of suspending operations during the remainder of the month save for the smaller actions already recorded. Fresh dispositions had to be made in order to meet the new German method o defence, which had abandoned the old trench system, and depended now upon scattered strong points, lightly held front lines, and heavy reserves with which to make immediate counter-attacks upon the exhausted stormers. The concrete works called also for a different artillery treatment, since they were so strong that an eighteen-pounder or even a 5.9 gun made little impression. These new problems all pressed for solution, and the time, like the days, was growing shorter.

The front of the new attack upon September 20 was about eight miles in length, and corresponded closely with the front attacked upon July 31, save that it was contracted in the north so that Langemarck was its limit upon this side. Upon the south the flank was still fixed by the Ypres-Comines Canal, just north of Hollebeke. The scheme of the limited objective was closely adhered to, so that no advance of more than a mile was contemplated at any point, while a thousand yards represented the average depth of penetration which was intended. The weather, which had given a treacherous promise of amendment, broke again upon the very night of the assembly, and the troops were drenched as they lay waiting for the signal to advance. Towards morning the rain stopped, but drifting clouds and a dank mist from the saturated soil deprived the attackers of the help of their aircraft —so serious a handicap to the guns. But the spirits of the men rose with the difficulties, after the good old British fashion, and at 5:40 on this most inclement morning, wet and stiff and cold, they went forward with cheerful alacrity into the battle.

The field of operations was now covered by two British armies, that of Gough in the north extending from beyond Langemarck to the Zonnebeke front, while Plumer’s Army covered the rest of the line down to Hollebeke. It may be said generally that the task of the men in the south was the more difficult, since they had farther to advance over country which had seemed to be almost impregnable. None the less the advance in the north was admirably executed and reached its full objectives. Cavan’s Fourteenth Corps still held the extreme north of the British line, but neither they nor the French upon their left were really engaged in the advance. They covered the front as far south as Schreiboom, where the right of the Twentieth Division joined on to the left of the Fifty-first Highlanders. This latter division formed the left flank of the main advance, though the 59th Brigade, the 60th Brigade, and the 2nd Brigade of Guards did push their line some short distance to the front, on either side of the Ypres—Staden Railway, the 59th Brigade capturing Eagle Trench and the 60th Eagle House. This was a very formidable position, crammed with machine-guns, and it took four days for its conquest, which was a brilliant feat of arms carried out by men who would be discouraged by no obstacle. The garrison were picked troops, who fought desperately, and everything was against the attack, but their pertinacity wore down the defence and eventually, upon Sept. 23, the 10th Rifle Brigade and the 12th Royal Rifles cleared up the last corner of the widespread stronghold.

The hard-worked Highland Territorials of the Fifty-first Division were worn with service but still full of fire. Their advance was also an admirable one, and by nine o’clock they had overcome all obstacles and dug in upon their extreme objective. Quebec Farm was a special stronghold which held the Highlanders up for a time, but finally fell to their determined assault. Rose Farm, Delva Farm, and Pheasant Farm were also strongly defended. About 10 A.M. many strong counter-attacks were made in this area, one of which for a time drove back the line of the Highlanders, but only for a short period. This particular attack was a very gallant one effected by Poles and Prussians of the Thirty-sixth and Two hundred and eighth Divisions. It was noted upon this day that the Prussians fought markedly better than the Bavarians, which has not always been the case. The method adopted both by the Highland Division and in some other parts of the line in order to overcome strong points, such as farms, was a concentration of portable trench-mortars firing heavy charges with a shattering effect. Pheasant Farm was a particularly difficult proposition, and yet it was so smothered by a cloud of these missiles that the distracted garrison was compelled to surrender. This use of what may be called a miniature and mobile heavy artillery became a feature of the last year of the War.

Next to the Fifty-first Division, and covering the ground to the north and east of St. Julien was the Fifty-eighth Division, a new unit of second line London Territorials which had done a good deal of rough service in the line, but had not yet been engaged in an important advance. Upon this occasion it bore out the old saying that British troops are often on their top form in a first engagement. Their advance was a brilliant one and attained its full objective, taking upon the way the strongly-fortified position of Wurst Farm. Nowhere in the line was the ground more sodden and more intersected with water jumps. The 173rd Brigade was on the. right, the 174th upon the left, the. former being led by the young hero of the Ancre Battle and the youngest Brigadier, save perhaps one, in the whole army. It was a magnificent battle debut for the Londoners and their coolness under fire was particularly remarkable, for in facing the difficult proposition of Wurst Farm they avoided making a frontal attack upon it by swinging first left and then right with all the workmanlike precision of veterans. The capture of Hubner Farm by the 2/6th and 2/8th London was also a particularly fine performance, as was the whole work of Higgins’ 174th Brigade.

The two divisions last mentioned, the Fifty-first and the Fifty-eighth, formed the fighting line of Maxse’s Eighteenth Corps upon this day. On their right was Fanshawe’s Fifth Corps, which had taken the place of the Nineteenth Corps. The most northern division was that sterling West Lancashire Territorial Division, the Fifty-fifth, which had now been in and out of the fighting line but never out of shell fire since the evening of July 31, or seven weeks in all. In spite of its long ordeal, and of the vile ground which lay at its front, it advanced with all its usual determination, the 164th Brigade upon the left, and ‘the 165th upon the right, each of them being stiffened by one battalion from the Reserve Brigade. The 8th Liverpool Irish were upon the extreme left, which moved down the left bank of the Hannebeek and struck up against the third difficult obstacle of Schuber Farm, which they succeeded, with the co-operation of the 2/4th London and of two Tanks, in carrying by assault. Farther south a second farm-house, strongly held, called the Green House, was carried by the 2/5th Lancashire Fusiliers, while the 4th North Lancashire took Fokker Farm upon the right. When one considers that each of these was a veritable fortress, stuffed with machine-guns and defended by 2nd Guards Reserve regiment, one cannot but marvel at the efficiency to which these Territorial soldiers had attained. The 4th Royal Lancasters kept pace upon the right. The advance of the 165th Brigade was equally successful in gaining ground, and there also were formidable obstacles in their path. After crossing the Steenbeek they had to pass a very heavy barrage of high explosives and shrapnel which, however, burst upon percussion and was neutralised to some extent by the softness of the ground. The line of advance was down the Gravenstafel road. A formidable line of trenches were carried and Kavnorth Post was captured, as were Iberian and Gallipoli, strong points upon the right. A counter-attack in the afternoon which moved down against the two brigades, was broken by their rifle-fire, aided by the advent of the two supporting battalions, the 5th South Lancashires and 5th North Lancashires. The ground thus taken was strongly held until next evening, September 21, when under cover of a very heavy fire the enemy penetrated once more into the positions in the area of the 164th Brigade. Just as darkness fell, however, there was a fine advance to regain the ground, in which the whole of the headquarters staff, with bearers, signallers, runners, and men-servants, swept up to the position which was captured once more. Among other positions taken upon September 20 was Hill 37, which had been so formidable a stronghold for the Germans in the murderous fighting of August 16. This commanding point was taken and held by the 5th, 6th, and 9th King’s Liverpools, with part of the 5th South Lancashires, all under the same officer who led the 36th Brigade in their fine attack upon Ovillers. The position was strongly organised, and upon the next day it beat back a very determined German counter-attack.

The Ninth Division was on the right of the Fifty-fifth with the South Africans upon the left flank. At the opening of the attack the 3rd (Transvaal) and 4th (Scottish) South African regiments advanced upon the German line. Within an hour the latter had carried Borry Farm, which had defied several previous assaults. At eight o’clock both these regiments had reached their full objectives and the supporting units, the 1st (Cape) and 2nd (Natal) regiments went through their ranks, the men of the Transvaal cheering the men of Natal and the Cape as they passed. By 9:30 the second objectives, including Beck House, had also fallen. There was a considerable concentration of Germans beyond, and the 6th Camerons came up in support, as an attack appeared to be imminent. The artillery fire dispersed the gathering, however, and the 2nd Regiment spreading out on the left to Waterend House established touch with the Lancashire men to their north. Bremen Redoubt had been captured, and this was made a nodal point against any counter-attack, as was Vampire Redoubt. By mid-day the 1st Regiment on the right had lost heavily and was forced to dig in and act upon the defensive as German concentrations were visible in the Hannebeke Woods. A second battalion of the 26th Brigade, the 7th Seaforths, were at this time sent up in support. The left flank was also checked and a defensive post organised at Mitchell’s Farm. The shelling from the direction of Hill 37 was very heavy, the more so as the Africans were ahead of the 165th Brigade upon their left. A number of German aeroplanes flying low and using their machine-guns complicated a situation which was already sufficiently serious, for the small-arm ammunition was running low and only a few hundred exhausted men with a thin sprinkling of officers remained in the fighting line. The artillery played up splendidly, however, and though the enemy massed together at Bostin Farm he could never get a sufficient head of troops to carry him through the pelting British barrage. Thus the day drew to a close with heavy losses cheerfully borne, and also with a fine gain of ground which included several of the most sinister strong points upon the whole line. The South Africans have been few in number, but it cannot be disputed that their record in the field has been a superb one.

In the meantime the 27th Brigade, upon the right of the South Africans, had also done a splendid day’s work. In the first dash the battalion upon the left front, the 12th Royal Scots, had taken Potsdam Redoubt with its garrison. Thence the line rolled on, the Scots Fusiliers and Highland Light Infantry joining in turn in the advance, until evening found them with the same difficulties and also with the same success as their African comrades. As night fell this right wing was in touch with the Australians near Anzac, and thence passed through the wood and along the railway bank to the junction with the left brigade, which in turn stretched across to Gallipoli and to Hill 37, which was now in the hands of their Lancashire neighbours and bristling with their machine-guns. That night the Ninth Division lay upon the ground that they had won, but the men had been without sleep or warm food for three days and nights under continual fire, so that, hardy as they were, they had nearly reached the limit of human endurance. It is worthy of remark that the wounded in this part of the field were attended to in many cases by captured German surgeons, and that one of these had an experience of Prussian amenities, for his brains were scattered by a sniper’s bullet.

The First and Second Australian Divisions joined the left unit of Plumer’s Army, but worked in close co-operation with the Ninth Division upon their right. In a day of brilliant exploits and unqualified successes there was nothing to beat their performance, for they were faced by that which tries the nerves of the stoutest troops—an area which has already been tested and found to be impregnable. With all the greater fire did the brave Australian infantry throw itself into the fray, and they had the advantage over their predecessors in that the line was well up on either side of them, and that enemy guns upon their flanks were too busy upon their own front to have a thought of enfilading. The result of the Australian advance was instant and complete, for the remainder of Glencorse Wood and Nonneboschen were over-run and by ten o’clock the “Diggers” were through the hamlet of Polygonveld and into the original German third line beyond it. The western part of Polygon Wood was also cleared, and so, after a sharp fight, was the strong point called “Black Watch Corner,” which is at the south-western extremity of the wood. At this point the advance of the Australians was not less than a mile in depth over ground which presented every possible obstacle. Over at least one of their captured redoubts their own Australian flag with the Southern Cross upon it was floating proudly in the evening. The losses of the division were serious, the greater part being due to an enfilade fire from the right, coming probably from the high ground in the south near Tower Hamlets, which struck their flank as they approached the south of Polygon Wood. Anzac upon the left marked their northern limit. Nothing could have been finer than the whole Australian attack. “They went into battle,” says their scribe, “not singing and laughing like many British regiments, but very grim, very silent, with their officers marching quietly at the head of each small string of men.” They are dour, determined fighters, flame-like in attack, iron in defence, and they have woven a fresh and brilliant strand into the traditions of the Imperial armies. It should be mentioned that it was the 2nd, 3rd, 5th, and 7th Brigades which carried forward the line to victory.

Good as the Australian advance had been it could not be said to have been better than Babington’s Twenty-third Division upon their right. They, too, had to cross ground which had been littered by the bodies of their comrades, and to pass points which brave men had found impassable. But all went well upon this day, and every objective was seized and held. Inverness Copse, of evil memory, was occupied at the first rush, and the advance went forward without a check to Dumbarton Lakes and on past them until the Veldhoek Ridge had fallen. A counter-attack which broke upon them was driven back in ruin. The advance was across the marshy Basseville Beek and through the dangerous woods beyond, but from first to last there was never a serious check. It was on the Yorkshires, the West Yorkshires, and the Northumberland Fusiliers of the 68th and 69th Brigades that the brunt of the early fighting fell, and as usual the North-country grit proved equal to the hardest task which could be set before it. The final stage which carried the Veldhoek Ridge was also a North-country exploit in this section of the line, as it was the 10th West Ridings and the 12th Durhams, who with fixed bayonets cleared the ultimate positions, reaching the western slopes of the upper Steenbeek Valley where they dug in the new temporary lines.

On the extreme south of the line the advance had been as successful as elsewhere, and at nearly every point the full objective was reached. Upon the right of the Twenty-third Division was the Forty-first, a sound English Division which had distinguished itself at the Somme by the capture of Flers. The leading brigades, the 122nd and 124th, with Royal Fusiliers, King’s Royal Rifles, and Hampshires in the lead, lost heavily in the advance. The snipers and machine-guns were very active upon this front, but each obstacle was in turn surmounted, and about 8:30 the Reserve Brigade, the 123rd, came through and completed the morning’s work, crossing the valley of the Basseville Beek and storming up the slope of the Tower Hamlets, a strong position south of the Menin road. Among the points which gave them trouble was the Papooje farm, which was found to be a hard nut to crack—but cracked it was, all the same. This same brigade suffered much from machine-guns east of Bodmin Copse, both it and the 124th Brigade being held up at the Tower Hamlet Plateau, which exposed the wing of the 122nd who had reached all their objectives. So great was the pressure that the Brigadier of the 124th Brigade came up personally to reorganise the attack. The 11th West Kent, the southern unit of the 122nd, had their right flank entirely exposed to German fire. Two young subalterns, Freeman and Woolley, held this dangerous position for some time with their men, but Freeman was shot by a sniper, the losses were heavy, and the line had to be drawn in. Colonel Corfe of the 11th West Kent and Colonel Jarvis of the 21st K.R.R. were among the casualties. In spite of all counter-attacks the evening found the left of the Forty-first Division well established in its new line, and only short of its full objective in this difficult region of the Tower Hamlets, where for the following two days it had to fight hard to hold a line. The losses were heavy in all three brigades.

On the right of the 41st and joining the flank unit of Morland’s Tenth Corps was the Thirty-ninth Division. This Division attacked upon a single brigade front, the 117th having the post of honour. The 16th and 17th Sherwood Foresters, the 17th Rifles, and the 16th Rifle Brigade were each in turn engaged in a long morning’s conflict in which they attained their line, which was a more limited one than that of the divisions to the north.

South of this point, and forming the flank of the whole attack, was the Nineteenth Division, which advanced with the West- countrymen of the 57th Brigade upon the right, and the Welshmen of the 58th Brigade upon the left. Their course was down the spur east of Zillebeke and then into the small woods north of the Ypres-Comines Canal. The 8th Gloucesters, 10th Worcesters, 8th North Staffords, 6th Wiltshires, 9th Welsh, and 9th Cheshires each bore their share of a heavy burden and carried it on to its ultimate goal. The objectives were shorter than at other points, but had special difficulties of their own, as every flank attack is sure to find. By nine o’clock the work was thoroughly done, and the advance secured upon the south, the whole Klein Zillebeke sector having been made good. The captors of La Boisselle had shown that they had not lost their power of thrust.

This first day of the renewed advance represented as clean-cut a victory upon a limited objective as could be conceived. The logical answer to the German determination to re-arrange his defences by depth was to refuse to follow to depth, but to cut off his whole front which was thinly held, and then by subsequent advances take successive slices off his line. The plan worked admirably, for every point aimed at was gained, the general position was greatly improved, the losses were moderate, and some three thousand more prisoners were taken. The Germans have been ingenious in their various methods of defence, but history will record that the Allies showed equal skill in their quick modifications of attack, and that the British during this year’s campaign had a most remarkable record in never being once held by any position which they attacked, save only at Cambrai. It is true that on some sections, as in the south of the line on August 16, there might be a complete check, but in every action one or other part of the attack had a success. In this instance it was universal along the line.

The Germans did not sit down quietly under their defeat, but the reserve counter-attack troops came forward at once. Instead, however, of finding the assailants blown and exhausted, as they would have been had they attempted a deep advance, they found them in excellent fettle, and endured all the losses which an unsuccessful advance must bring. There were no less than eleven of these attempts upon the afternoon and evening of September 20, some of them serious and some perfunctory, but making among them a great total of loss. They extended over into September 21, but still with no substantial success. As has already been recorded, the front of the 55th Division, at Schuler Farm, east of St. Julien, was for a time driven in, but soon straightened itself out again. In this advance, which embraced the whole front near St. Julien, the German columns came with the fall of evening driving down from Gravenstafel and following the line of the Roulers Railway. They deployed under cover of a good barrage, but the British guns got their exact range and covered them with shrapnel. They were new unshaken troops and came on with great steadiness, but the losses were too heavy and the British line too stiff. Their total lodgment was not more than 300 yards, and that they soon lost again. By nine o’clock all was clear.

Among the British defences the ex-German pill-boxes were used with great effect as a safe depository for men and munitions. This considerable German attack in the north was succeeded next day by an even larger and more concentrated effort which surged forward on the line of the Menin road, the fresh Sixteenth Bavarian Division beating up against the Thirty-third and the Australian Divisions. There was some fierce give-and-take fighting with profuse shelling upon either side, but save for some local indentations the positions were all held. The Victorians upon the right flank of the Australians’ position at Polygon Wood were very strongly attacked and held their ground all day. Finney’s Thirty-third Division had come into line, and the German attack upon the morning of September 25 broke with especial fury upon the front of the 98th Brigade, which fought with a splendid valour which marks the incident as one of the outstanding feats of arms in this great battle. Small groups of men from the two regular battalions, the 1st Middlesex and the 2nd Argyll and Sutherlands, were left embedded within the German lines after their first successful rush, but they held out with the greatest determination, and either fought their way back or held on in little desperate groups until they were borne forward again next day upon the wave of the advancing army.

The weight of the attack was so great, however, that the front of the 98th Brigade was pushed back, and there might have been a serious set-back had it not been for the iron resistance of the 100th Brigade, who stretched south to the Menin road, joining hands with the 1 1th Sussex of the Thirty-ninth Division upon the farther side. The 100th Brigade was exposed to a severe assault all day most gallantly urged by the German Fiftieth Reserve Division and supported by a terrific bombardment. It was a to terrible ordeal, but the staunch battalions who met it, the 4th Liverpools who linked up with their comrades of the 98th Brigade, the 2nd Worcesters, 9th Highland Light Infantry, and 1st Queens, were storm-proof that day. On the Menin road side the two latter battalions were pushed in for a time by the weight of the blow, and lost touch with the Thirty-ninth Division, but the Colonel of the Queens, reinforced by some of the 16th K.R.R., pushed forward again with great determination, and by 9 A.M. had fully re-occupied the support line, as had the 9th Highland Light Infantry upon their left. So the situation remained upon the night of the 25th, and the further development of the British counter-attack became part of the general attack of September 26. It had been a hard tussle all day, in the course of which some hundreds in the advanced line had fallen into the hands of the enemy. It should be mentioned that the troops in the firing-line were occasionally short of ammunition during the prolonged contest, and that this might well have caused disaster had it not been for the devoted work of the 18th Middlesex Pioneer Battalion who, under heavy fire and across impossible ground, brought up the much-needed boxes and bandoliers. The resistance of the Thirty-third Division was greatly helped by the strong support of the Australians on their flank. It was a remarkable fact, and one typical of the inflexibility of Sir Douglas Haig’s leadership and the competence of his various staffs, that the fact that this severe action was raging did not make the least difference in his plans for the general attack upon September 26.

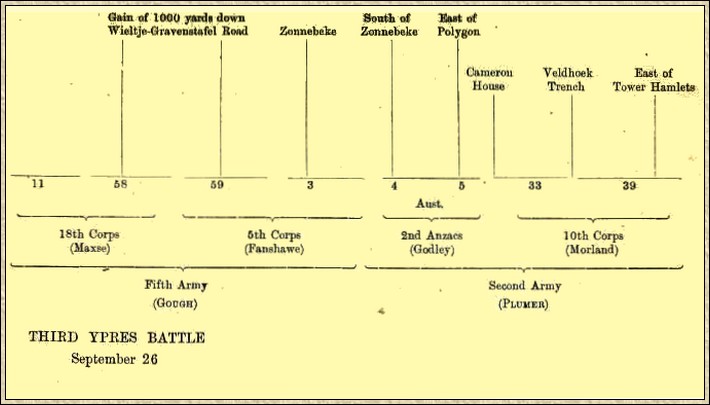

At 5:50 in the morning of that date, in darkness and mist, the wonderful infantry was going forward as doggedly as ever over a front of six miles, extending from the north-east of St. Julien to the Tower Hamlets south of the Menin road. The latter advance was planned to be a short one, and the real object of the whole day’s fighting was to establish a good jumping-off place for an advance upon the important Broodseinde Ridge. Some of the war- worn divisions had been drawn out and fresh troops were in the battle line. The Northern Corps was not engaged, and the flank of the advance was formed by the Eleventh Division (Ritchie) with the 58th Londoners upon their right, the two forming the fighting front of Maxse’s Eighteenth Corps. Their advance, which was entirely successful and rapidly gained its full objectives, was along the line of St. Julien-Poelcapelle road. The total gain here, and in most other points of the line, was about 1000 yards.

Upon the right of Maxse’s Corps was the Fifty-eighth Division, which also secured its full objective. The German line upon this front was held by the Twenty-third Saxon Division (Reserve), which yielded a number of prisoners. The Londoners fought their way down the line of the Wieltje-Gravenstafel road, overcoming a series of obstacles and reaching the greater portion of their objectives. There were no notable geographical points to be captured, but the advance was a fine performance which showed that the Fifty-eighth was a worthy compeer of those other fine London territorial divisions which had placed the reputation of the mother city at the very front of all the Imperial Armies. The Forty-seventh, the Fifty-sixth, the Fifty-eighth, and the Sixtieth in Palestine had all shown how the citizen-soldier of the Metropolis could fight.

Fanshawe’s Corps consisted upon this date of the Fifty-ninth Division upon the left, and the Third upon the right. The Fifty-ninth Division, which consisted of second-line battalions of North Midland Territorials, made a fine advance upon the right of the Gravenstafel road, keeping touch with the Londoners upon the left. Here also almost the whole objective was reached. The German positions, though free from fortified villages, were very thick with every sort of mechanical obstruction, in spite of which the attack went smoothly from start to finish. It is clear that the British advance was fully expected at the south end of the line, but that for some reason, probably the wretched state of the ground, it was not looked for in the north.

The Third Division had kept pace with the Australians to the south and with the Midlanders to the north, and had captured the village and church of Zonnebeke, which formed their objective. Very strong counter-attacks upon all the part of the land to the immediate north of Polygon Wood were beaten down by the masterful fire of the British artillery.

To the right of the Fifth Corps the Australians k pursued their victorious career,, going to their M full limit, which entailed the possession of the whole of Polygon Wood. The Fourth and Fifth Divisions were now in the battle line. Pushing onwards they crossed the road which connects Bacelaer with Zonnebeke, and established themselves firmly on the farther side south of Zonnebeke. Some 300 prisoners with a number of machine-guns were taken in this fine advance. The pressure upon the Australians was especially heavy upon the right flank of the Fifth Australian Division, since the left of the Thirty-third Division had been driven in, as already described, by the very heavy German attacks upon September 25, so that the Victorians of the 15th Australian Brigade at the south end of the line started with their flank exposed. They were in close touch throughout with the 19th Brigade of the British Division, and the 2nd Welsh Fusiliers found themselves intermingled with the Victorians in the advance, with whom they co-operated in the capture of Jut Farm. It was a fine feat for the Victorians to advance at all under such circumstances, for as they went forward they had continually to throw out a defensive flank, since the Germans had re-occupied many of the trenches and Mebus, from which they had been ejected upon the 20th. This strip of ground remained for a time with the Germans, but the Thirty-third Division had also advanced upon the right of it, so that it was left as a wedge protruding into the British position. Cameron House was taken at the . joining point of the two divisions, and gradually the whole of the lost ground was re-absorbed.

To the right of the Australians the Thirty-third Division went forward also to its extreme objective, gathering up as it went those scattered groups of brave men who had held out against the German assault of the preceding day. This gallant division had a particularly hard time, as its struggle against the German attack upon the day before had been a very severe one, which entailed heavy losses. Some ground had been lost at the Veldhoek Trench north of the Menin road, where the 100th Brigade was holding the line, but this had been partially regained, as already described, by an immediate attack by the First Queen’s West Surrey and 9th Highland Light Infantry. The 2nd Argyll and Sutherlands were still in the front line, but for the second time this year this splendid battalion was rescued from the desperate situation which only such tried and veteran soldiers could have carried through without disaster. Immediately before the attack of September 26, just after the assembly of the troops, the barrage which the Germans had laid down in order to cover their own advance beat full upon the left of the divisional line, near Glencorse Wood, and inflicted such losses that it could not get forward at zero, thus exposing the Victorians, as already recorded. Hence, although the 100th Brigade succeeded in regaining the whole of the Veldhoek Trench upon the right, there was an unavoidable gap upon the left between Northampton Farm and Black Watch Corner. The division was not to be denied, however, and by a splendid effort before noon the weak spot had been cleared up by the Scottish Rifles, the 4th King’s Liverpools, and the 4th Suffolks, so that the line was drawn firm between Veldhoek Trench in the south and Cameron House in the north. A counter-attack by the Fourth Guards Division was crushed by artillery fire, and a comic sight was presented, if anything can be comic in such a tragedy, by a large party of the Guards endeavouring to pack themselves into a pill-box which was much too small to receive them. Many of them were left lying outside the entrance.

Farther still to the right, and joining the flank of the advance, the Thirty-ninth Division, like its comrades upon the left, found a hard task in front of it, the country both north and south of the Menin road being thickly studded with strong points and fortified farms. It was not until the evening of September 27, after incurring heavy losses, that they attained their allotted line. This included the whole of the Tower Hamlets spur with the German works upon the farther side of it. The extreme right flank was held up owing to German strong points on the east of Bitter Wood, but with this exception all the objectives were taken and held by the 116th and 118th, the two brigades in the line. The fighting fell with special severity upon the 4th Black Watch and the 1st Cambridge of the latter brigade, and upon the 14th Hants and the Sussex battalions of the former, who moved up to the immediate south of the Menin road. The losses of all the battalions engaged were very heavy, and the 111th Brigade of the Thirty-seventh Division had to be sent up at once in order to aid the survivors to form a connected line.

The total result of the action of September 26 was a gain of over half a mile along the whole front, the capture of 1600 prisoners with 48 officers, and one more proof that the method of the broad, shallow objective was an effective answer to the new German system of defence by depth. It was part of that system to have shock troops in immediate reserve to counter-attack the assailants before they could get their roots down, and therefore it was not unexpected that a series of violent assaults should immediately break upon the British positions along the whole newly- won line. These raged during the evening of September 26, but they only served to add greatly to the German losses, showing them that their ingenious conception had been countered by a deeper ingenuity which conferred upon them all the disadvantages of the attack. For four days there was a comparative quiet upon the line, and then again the attacks carried out by the Nineteenth Reserve Division came driving down to the south of Polygon Wood, but save for ephemeral and temporary gains they had no success. The Londoners of the Fifty-eighth Division had also a severe attack to face upon September 28 and lost two posts, one of which they recovered the same evening.

Up to now the weather had held, and the bad fortune which had attended the British for so long after August 1 seemed-to have turned. But the most fickle of all the gods once more averted her face, and upon October 3 the rain began once more to fall heavily in a way which announced the final coming of winter. None the less the work was but half done, and the Army could not be left under the menace of the commanding ridge of Paschendaale. At all costs the advance must proceed.

Third Ypres Battle, September 26, 1917