III. Continuation of the Operations of Rawlinson’s Fourth Army

From August 22 to the Battle of the Hindenburg Line, September 29

Further advance of the Australians—Of the Third Corps—Capture of Albert —Advance across the old Somme battlefield—Capture of Mont St. Quentin —Splendid Australian exploit—Fall of Peronne—Début of the Yeomanry (Seventy-fourth) Division—Attack on the outliers of the Hindenburg Line —Appearance of the Ninth Corps—Eve of the Judgment

We have now reached the date when Byng’s Third Army joined in the fray, and it is necessary to find some means of co-ordinating the narrative and carrying it on in definite stages. The next well-marked crisis which affects each of the armies engaged is the great general attack on September 29, which broke the Hindenburg Line. Therefore, in separate chapters the operations of each army will be brought up to that date, and then further chapters will cover the doings of each up to the date of the Armistice. Since we have dealt with the Fourth Army, we may as well continue with it now until we are in close touch with the Hindenburg Line, premising only that instead of an inert neighbour upon the left we have a very active advancing British Army. We shall then go on to the Third and to the First Armies, and bring each of them in turn up to the same point.

On August 22 and the following days, the Fourth Army, with only two Corps—the Third and the Australians—in front, renewed its attack, greatly strengthened by the movement of the Third Army on its left, which ensured that at least five British corps were all moving forward together, distributing the advance over so wide an area that the Germans were less able to concentrate reserves of men or of guns at any one point—a result which was much aided by the fine work of General Mangin’s Army on the right.

The main part of the fighting on the front of the Fourth Army on August 22 was north of the Somme, where the Third Australian Division covered the right flank of the Third Corps. On the south of the river the Australian Corps advanced on a front of 4½ miles, and took all their limited objectives, which represented a depth of 1½ miles. This was effected by the Fifth Australian Division on the right and the Fourth on the left, supported and finally supplanted by the First Australian and Lambert’s Thirty-Second British Divisions, the latter on the right. The advance, which began at dawn, was no easy one, as the country was much cut about with many obstacles, seamed with trenches, and dotted with scattered woods.

The determined infantry would take no denial, however, and Herleville, Chuignies, and several other small village sites were captured. The heaviest fighting was in the woods, but a skilful system of encircling points of danger had been carefully worked out, and the losses were less than might have been anticipated. Sixteen guns, 80 officers, and 2463 men were the trophies of the day. Early in the morning of August 24 the Third Australian Division moved suddenly forward north of the river, captured the town of Bray, and formed a permanent line upon the further side. On August 25 this same unit advanced 3000 yards on a 4000-yard front with very little resistance, always covering the right of the Third Corps.

Let us now follow the work of this Corps from August 22 onwards.

It covered the ground from Albert in the north, where it was working in close liaison with the Welsh Division on the right of the Fifth Corps, down to a point near the Somme where it was in touch with the Australians. The immediate object of the operations was to eject the enemy from the positions in and around Albert which he had held for four months, and also from his whole defensive system opposite to the Amiens defence line, which latter had been regained in the previous fighting. On the day of battle the Forty-seventh London Division was on the right of the Corps line, the Twelfth Division in the centre, and the Eighteenth Division on the left. To this last was confided the difficult and important operation of clearing Albert, and of establishing light bridges over the Ancre so as to cross that stream and attack the high ground east of the town on the Becourt Road. There was to be no preliminary bombardment, but machine-gun and artillery barrages were to cover the infantry.

The zero hour was 4.45, and at the signal the Forty-seventh and Twelfth Divisions advanced behind a creeping barrage, moving at the rate of 100 yards in four minutes, and as thick as 250 field-guns could make it. With such a van of destruction in front the infantry came forward without undue losses, though a particular strong point named the Pear Tree just on the inter-divisional boundary held fast and was destined to give trouble for several days to come. As an observer remarked, “Anything British, from a helmet to a tank, which showed over the crest was met by the sweeping fire of many machine-guns, while shells from trench mortars fell in the ranks of men following up. It was only when the general attack was continued that this hornet’s nest could be cleared.” Save for this point the general objectives marked out for these divisions, which meant an advance of between two and three miles, were successfully made good, but an attempt to follow up with cavalry and whippet tanks could not be persevered in, so stiff was the opposition. It was soon found that the enemy in the Forty-seventh Division sector was not only capable of defence, but of aggression, for about 4 in the afternoon his infantry advanced in a strong attack with a powerful artillery backing, and drove with such violence into the 22nd, 23rd, and 24th Londons, forming the 142nd Brigade, that they were temporarily thrown back. Their right held firm, however, as did the Third Australian Division to the south, so that no gap was formed. Being reinforced by the 175th Brigade from the Fifty-eighth Division in reserve, the Londoners soon reformed their ranks, greatly thinned both by their advance in the morning and by the German onslaught in the afternoon. The enemy’s front was so menacing that the rest of the day and part of August 23 were spent in reorganisation and consolidation.

Meanwhile on the left, Lee’s Eighteenth Division, a famous all-English unit of the type which, however brilliant its comrades, has always formed the solid core of the magnificent tireless Imperial Army, was carrying out its difficult task at Albert. It had two brigades in the line, the 54th to the south and the 55th to the north of the town. The Germans in front held the line of the Ancre, with Albert as a bridgehead, the ruins and cellars of the town being sown with snipers and machine-guns. To clear the town, to occupy the high ground to the east, and by these operations to cover the flanks of two armies was the function of this Division, and also to secure crossings at Albert by which the Welsh on their left could get across.

The stream in this part was 6 feet deep and 14 wide, with swampy banks strongly held by the enemy. There were unguarded bits, however, and patrols got across on the 21st, which simplified the task, though it deranged at the last moment all the preparations for barrage. Part of the 6th Northamptons and the 11th Royal Fusiliers crossed early on the 22nd and formed up along the edge of the Albert—Meaulte Road, while the rest of the 6th Northamptons fought hard for elbow-room on the right flank, working in close liaison with the 36th Brigade on the left of the Twelfth Division who were attacking Meaulte. About 6 the whole front line advanced in this quarter, flooding over the scattered German posts, and capturing eighty machine-guns with their crews. At the same time the 8th East Surreys on the left had rushed Albert, and after some fine confused fighting had cleared the ruins and taken the whole town, with the river crossings. The 7th Buffs at once pushed out on the Albert—Pozières road, but were held up by very heavy fire. The 11th Royal Fusiliers further south had also been held up by the guns on the summit of Shamrock Hill, east of the town, but a company of the 2nd Bedfords, led by Captain Doake, captured this strong point and the line went forward. Altogether it was a good day’s work, and save on the extreme left most of the objects were attained at the cost of reasonable casualties, which included General Sadleir-Jackson of the 54th Brigade, who was badly wounded in the leg. The 53rd Brigade continued their advance up to 10 P.M., so as to gain the high ground on the Becourt Road, and thus prepare for the next day’s operations.

The 113th Brigade of the Welsh Division on the left had been passed over by the Albert bridges, and the 53rd had also passed in the night. The plan of August 23 was that these two brigades should attack Usna and Tara Hills respectively, on the high ground to the west of Becourt Wood. The Usna attack is described under the operations of the Fifth Corps. The Tara attack was completely successful, and four tanks rendered conspicuous service. The work was carried out by the 10th Essex, 7th West Kents, and the 7th Queen’s from the 55th Brigade. It was a fine military feat, far more important than 350 prisoners would imply, for it broke the girdle round Albert and cleared the road for the advance. No progress was made at the other portions of the corps front on this date, save for some advance on the left of the Twelfth Division near Meaulte.

It had been determined to keep up incessant pressure, and to test Hindenburg’s incautious maxim that the side with the best nerves would wear down the other. At 1 A.M. on August 24 the whole line burst into flame once more, and under a clear moon the Army rolled forward. On the right the Forty-seventh Division had ample revenge for its temporary check, as its 140th, together with the 175th Brigade of the Fifty-eighth Division, Londoners all, swept across the debated land of the Happy Valley and secured it. The Eighteenth Division also made good its objectives, the chief impediment being the historical mine craters of 1916 at La Boiselle; 250 prisoners were taken out of these by the 8th Royal Berks, a party of whom under Captain Nicholson, covered by Captain Sutherst’s 53rd Trench Mortar Battery, cleared up this difficult point. In the morning the Eighteenth Division was well to the east of Becourt. The only check was in the centre, where the general advance of the Twelfth Division was still held up by that Pear Tree strong point which had already caused so much trouble. Before evening, however, it was clear that the enemy was effecting a general retreat, and the 37th Brigade was able to take possession of this very well defended portion of the ridge.

It was clear now that the German front was crumbling, and the whole British line was pushing ahead. The chief obstacle on the morning of August 25 came from an all-pervading mist. There was no check, however, anywhere in the advance up to 2 P.M., when the general line of the front was up to Mametz. The hardest fighting of the day was done at Billon Wood by the 173rd Brigade, all three battalions, the 2/2nd, 3rd, and 2/4th London, having real hard work, and standing to it like men. The place was strongly held with powerful artillery support, but it had been cleared before nightfall. By the same hour the Twelfth Division was east of Mametz, and the 8th East Surreys were on the far side of Mametz Wood. As these familiar places came once more into their possession the troops felt that the tide had indeed turned. On August 26 the Eighteenth Division had cleared the ruins of Montauban, and the Twelfth, Carnoy, while the Fifty-eighth pushed on from Billon Wood, and wound up within a few hundred yards of Maricourt. This village was passed the next day, and altogether, on August 27 and 28, another three miles were added to the advance of the Twelfth and Fifty-eighth Divisions, the progress never ceasing, but being continually accompanied by fighting and maintained always against severe artillery fire. The Germans had thrown in three fresh divisions upon this front and the resistance was still very stiff.

This was especially evident at Trones Wood, which was carried for the second time in this way by the Eighteenth Division on August 27. This fine assault was made by the 8th Berks and 7th West Kents, who carried it out with both flanks open to the enemy since the Welsh had been held in front of Delville. So heavy were the losses that the Berkshires were in danger of not being strong enough to hold what they had gained, so the 10th Essex were pushed into the fight. At 8 A.M. on August 27 a German Guards battalion drove through Trones Wood and pushed out the British stormers, but they held on by their teeth to the eastern edge of Bernafoy Wood. Here General Barker of the 53rd Brigade reorganised his very weary ranks, which had been greatly mixed in the advance and retreat. Just as evening was falling the remains of the gallant brigade darted forward once more and came to grips with the Francis Joseph Prussian Guards, who lay with many a machine-gun among the brushwood. Led by Colonel Banks of the 8th Berkshires, the English infantry rushed into the wood and poured over the German position, taking forty machine-guns and completely overcoming the resistance. It was a fine exploit, and when the 53rd Brigade gave place to the 54th on the morning of August 28 they handed over to them the whole of this terrible grove, which has been so drenched by the bravest blood of two great nations. There was no further action in this quarter on August 28, but on the 29th the 54th Brigade, now under Colonel Perceval, was heavily engaged. Guillemont was passed, though no trace of this large village could be distinguished, and all day the 2nd Bedfords on the left and the 6th Northants on the right were working forward across the grim old battlefield. On August 28 the Twelfth Division took Hardecourt, and General Higginson, who may well have been disturbed by the constant flow of youngsters into his ranks to take the place of his disabled veterans, must have had his fears removed and his heart gladdened by the splendid conduct that day of 250 men of the 9th Royal Fusiliers under Colonel Van Someren, none of whom had been in France more than three weeks. On August 30 a great centre of German resistance was Priez Farm, which held up the 11th Royal Fusiliers, and also the Forty-seventh Division which had taken the place of the Twelfth in the centre of the corps. The enemy was clinging hard to Morval, also in the Welsh area, and this made any advance on the front of the Eighteenth Division impossible. It was clear that a regular battle with artillery preparation was needed, and this was arranged for September 1. The right wing of the corps had in the meantime got to the line of Maurepas, and on August 31 the Forty-seventh Division in the centre made a good advance up to Long Wood with a number of prisoners to show for it. The Fifty-eighth Division closed in upon Marrières Wood, which they took after some heavy fighting, avenging the brave South Africans who had died so gallantly there five months before. It was clear that the enemy were now standing in a strong line, and were by no means beaten, which was shown also by the bearing of the prisoners, whose morale was high, and who spoke with as much pride and assurance as ever of the ultimate military success of their country. Yet during the last week they had been steadily driven back some 3000 yards every day by the remorseless barrage of the British guns followed by the disciplined rush of the British infantry.

We shall now leave the Third Corps for a time at this line of fixed resistance and return to consider the advance of the Australians to the south. This had been victorious and unbroken, though no very serious resistance had to be overcome. Smoke by day and fire by night, with explosions at all hours, heralded the German retreat. On August 26 Cappy was occupied. On the 27th Vaux Wood was occupied north of the river, while Foucaucourt and Vermandovillers were submerged to the south, villages no longer, but at least marks of progress upon the map. On the 28th the Germans were still retreating with the toes of the Australians upon their very heels, but the heavier shelling warned General Monash that there was a fixed line ahead, as might well be expected, since his men were now nearing the point where the bend of the Somme brought the river right across their front. Dompierre, Fay, Estrées, and other old centres of contention were taken that day. On the 29th the 3rd Australians got Hem, while on the south the rest of the corps advanced 2000 yards to the bank of the river, taking the whole line of villages from Biaches to Villers-Carbonnel. The task of capturing such places was much complicated by the difficulty of knowing where they were after you had got them. The present writer was in Carbonnel, which was a considerable place, some weeks later, and was unable to find any trace of habitation save a signboard upon which was printed the words: “Here was the village of Villers-Carbonnel.”

At the end of August the resistance had stiffened, and it was clear that the Germans meant to take advantage of the unique situation of Peronne in order to make it a strong centre of resistance. To the civilian observer it would have seemed that such a place was impregnable against assault, for it is girt in with reedy marshes on the west, and with a moat on the north, while the south is defended by the broad river, even as in the days when Quentin Durward formed part of the garrison. Yet the Australians took it in their stride by a mixture of cleverness and valour which must have greatly rejoiced General Rawlinson, who saw so formidable an obstacle removed from his path. As a preliminary operation the Third Australian Division had taken Clery in the north, which they held against a vigorous counter-attack on September 30. Halles was afterwards captured. The question now was how to approach the town. Immediately to the north of it there lies a formidable hill, well marked, though of no great height. This place, which is called Mont St. Quentin, commanded all approaches to the town as well as the town itself. The Germans had recognised the importance of the position and had garrisoned it with picked troops with many machine-guns. Standing upon its pitted crest, where one is often ankle-deep in empty cartridges, one cannot imagine as one looks west how a rabbit could get across unscathed. This was the formidable obstacle which now faced the Australians.

They went at it without a pause and with characteristic earnestness and directness, controlled by very skilful leadership. Two brigades, the 5th and 6th of Rosenthal’s Second Australian Division, had been assembled on the north of the Somme bend, the men passing in single file over hastily constructed foot-bridges. By this means they had turned the impassable water defences which lie on the westward side of Peronne, but they were faced by a terrible bit of country, seamed with trenches, jagged with wire, and rising to the village of St. Quentin, which is a little place on the flank of the hill. The hill itself is crowned by a ragged wood some acres in extent. Mont St. Quentin lies about equidistant, a mile or so, from Peronne in the south, and from the hamlet of Feuillaucourt in the north. On this front of two miles the action was fought.

Early in the morning of August 31 the 5th Brigade, under General Martin, advanced upon the German position. The 17th Battalion was in the centre opposite to Mont St. Quentin. The 19th was on the right covering the ground between that stronghold and Peronne, the 20th on the left, extending up to Feuillaucourt, with that village as one of its objectives. The 18th was in close support. A very heavy and efficient artillery bombardment had prepared the way for the infantry assault, but the defending troops were as good as any which Germany possessed, and had endured the heavy fire with unshaken fortitude, knowing that their turn would come.

From the moment that the infantry began to close in on the German positions the battle became very bitter and the losses very serious. The 19th Battalion on the right were scourged with fire from the old fortified walls of Peronne, from St. Denis, a hamlet north of the town, and from scattered woods which faced them. Every kind of missile, including pineapple-bombs and rifle-grenades, poured down upon them. The long thin line carried on bravely, halted, carried on once more, and finally sank down under such poor cover as could be found, sending back a message that further artillery bombardment was a necessity. On the left of the attack the 20th Battalion seems to have had a less formidable line before it, and advancing with great speed and resolution, it seized the village of Feuillaucourt. In the centre, however, a concentration of fire beat upon the 17th Battalion, which was right under the guns of Mont St. Quentin. Working on in little groups of men, waiting, watching, darting forward, crouching down, crawling, so the scattered line gradually closed with its enemy, presenting a supreme object lesson of that individual intelligence and character which have made the Australian soldier what he is. A little after 7 o’clock in the morning the survivors of two companies drew together for the final rush, and darted into the village of Mont St. Quentin, throwing out a line of riflemen upon the far side of it. On that far side lay the culminating slope of the hill crowned with the dark ragged trees, their trunks linked up with abattis, laced with wire, and covering machine-guns. The place was still full of Germans and they had strong reserves on the further side of the hill.

The 17th had reached their goal, but their situation was very desperate. Their right was bent back and was in precarious contact with the 19th Battalion. Their left flank had lost all touch. They were a mere thin fringe of men with nothing immediately behind them. Two companies of the supporting battalion had already been sent up to stiffen the line of the 19th Battalion, and the remaining two companies were now ordered forward to fill the gap between the 17th and 20th. Not a rifle was left in reserve, and the whole strength of the Brigade was in the firing-line. It was no time for hedging, for everything was at stake.

But the pressure was too severe to last. The Australian line could not be broken, but there comes a point when it must bend or perish. The German pressure from the wood was ever heavier upon the thin ranks in front of it. A rush of grey infantry came down the hill, with showers of bombs in front of them. One of the companies in the village had lost every officer. The fire was murderous. Guns firing over open sights had been brought up on the north of the village, and were sending their shells through the ruined houses. Slowly the Australians loosened their clutch upon their prize and fell back to the west of the village, dropping down in the broken ground on the other side of the main Peronne Road, and beating back five bombing attacks which had followed them up. Still the fire was murderous, and the pressure very heavy, so that once more, by twos and threes, the survivors fell back 250 yards west of the road, where again they lay down, counting their dwindling cartridges, and dwelling upon their aim, as the grey crouching figures came stealthily forward. The attack was at an end. It had done splendidly, and it had failed. But the scattered survivors of the 5th Brigade still held on with grim tenacity, certain that their comrades behind would never let them down.

All night there was spasmodic fighting, the Germans pushing their counter-attack until the two lines were interlocked and the leading groups of the 5th Brigade were entirely cut off. In some places the more forward Germans finding a blank space—and there were many—had pushed on until they were 500 yards west of the general line of the 5th Brigade. Thus when Robertson’s 6th Brigade attacked at an early hour of September 1, they came on German infantry posts before they connected up with the main line of their own comrades. Their advance had been preceded by a crashing bombardment from everything which would throw a projectile, so that the crest of the hill was fairly swept with bullets and shells. Then forward went the line, the 23rd Battalion on the right, the 24th on the left, 21st and 22nd in support. From the start the fire was heavy, but all opposition was trampled down, until the two leading battalions were abreast of the hill. Then once more that terrible fire brought them to a halt. The 23rd on the right was held by the same crossfire which had beaten upon the 19th the day before. Its losses were heavy. The 24th got forward to Feuillaucourt and then, having occupied it, turned to the right and endeavoured to work down to Mont St. Quentin from the north. But the fire was too murderous and the advance was stopped. Other elements were coming into action, however, which would prevent the whole German effort being concentrated upon the defence of the one position. In the north the 10th Brigade of the Third Australian Division, with the 229th British Yeomanry Brigade upon their left, were swinging round and threatening to cut in on the German flank and rear. In the south the 14th Australian Brigade of the Fifth Division was advancing straight upon the town of Peronne, attacking from the south and east simultaneously. But even now the nut was too hard for the crackers. The British and the 10th Australian Brigades were fighting their way round in the north and constant progress was being made in that indirect pressure. But the 6th Brigade after its splendid advance was held up, and old Peronne, spitting fire from its ancient walls, was still keeping the 14th Brigade at a distance. At 8 o’clock the attack had again failed. Orders were then given for the reorganisation of the troops and for a renewed effort at half-past one. The artillery had been brought up and reinforced, so that it now fairly scalped the hill. At the hour named the direct advance of the 6th Brigade was resumed, the fresh 21st Battalion being pushed into the centre, between the 23rd and 24th which had both suffered severely in the morning. This time General Rosenthal was justified of his perseverance. At the signal the troops poured forward and under a hail of bullets seized the ruins of the village once more, streaming out at the further side and falling into a long skirmish line on the western edge of the wood. The brave German defenders were still unabashed and the losses were so heavy that the wood could not instantly be carried, but the position was consolidated and held, with the absolute certainty that such close grips in front with the threatening movements upon his flank must drive him from the hill. So it proved, for when on the morning of September 2 the 7th Brigade passed over the fatal plain, which was sown with the bodies of their comrades, they went through the village and on past the wood with little opposition, forming up at last in a defensive line facing south-east, while the Fifth Division on the south drove home its attack upon Peronne, where the defence was already hopelessly compromised by the various movements to the north.

Thus fell Mont St. Quentin, and as a consequence Peronne. Sir Henry Rawlinson in his official dispatch remarked that he was “filled with admiration for the surpassing daring” of the troops who had taken a position of the greatest “natural strength and eminent tactical value.” Men of the Second Guards Division and of four other German Divisions were found among the prisoners. The Australian exploit may be said to have been of a peculiarly national character, as there was not one of the Australian communities—Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland, West Australia, Tasmania—which did not play some honourable part in the battle.

Passing northward from the victorious Australians, September 1 saw the attack carried all along the line, the 3rd Corps advancing upon Rancourt, Priez Farm, and the line to Bouchavesnes. On the left the hard-worked 54th and 55th Brigades did splendidly, especially the 8th East Surrey under Colonel Irwin. Surrey men and Germans lay thick round Priez Farm, but this key-position remained in the hands of the English, after a very bitter struggle. The 7th Queen’s took Fregicourt, while the 7th West Kents helped the Welshmen at Sailly-Sallisel. The trench mortar batteries, pushing right up regardless of all risk and smothering the German strong points by their concentrated fire, did great work in these operations, especially the 142nd T. M. Battery near Priez Farm. All these various advances were as remarkable for their tactical skill as for the valour shown by all ranks. The latter had been a constant asset, but the former grew with time.

Meanwhile the Forty-seventh and Fifty-eighth Divisions had each done splendidly and secured their objectives, including Rancourt and Bouchavesnes. The main road from Bapaume to Peronne had been passed and the whole of the old Somme battlefield been cleared in this direction. Prisoners were taken from four different divisions in the course of the fight. It had taken four months’ fighting in 1916 to conquer the ground which had been now cleared by the Fifth and Third Corps inside of ten days.

The advance was continued on September 2, as it was argued that however exhausted the victors might be the vanquished would surely be even more so. A new actor made a first appearance in the greatest of all dramas about this time, for the Seventy-fourth Division, which had done good service in Palestine under General Girdwood, made its first attack in a European line of battle. This unit was originally composed entirely of Yeomanry, and it had still retained a large proportion of this splendid material in the ranks, with a broken spur as their witty and picturesque divisional emblem. The tale of the British Yeomanry in the East is one which will be among the most romantic in the war; and the way in which farmers’ sons from Dorset or Fife charged with cold steel and rode down the Eastern cavalry or broke the ranks of the Turkish infantry is as fantastic an incident as the mind of a prophetic novelist could have furnished. Indeed it may be said generally that none of the many imaginary forecasts of the coming war equalled the reality in the broad sweep of its incidents and the grotesque combinations which ensued.

The Seventy-fourth had now taken over from the Fifty-eighth Division. They were pushed at once into heavy fighting, advancing rapidly down the western slope of the Tortille valley, through Moislains, and over the canal. In their eager zeal they had not mopped up sufficiently, and they soon found themselves under a fire from front and rear which no troops could endure. They were driven back to near the point from which they started and their losses were considerable. The Australians formed a defensive flank on the south, and the Forty-seventh on the north, and a line of resistance was built up between them from Haut Allaines on the right to the western bank of the Tortille. The Yeomanry had before evening endured a very terrible welcome to the Western front.

The Eighteenth Division on the left had also had some severe fighting which fell chiefly upon the depleted 53rd Brigade. It secured the high ground in the north of St. Pierre Vaast Wood, the whole of which was cleared by the 8th Berkshires. On September 3 and 4 the division continued to advance across the canal and the Tortille upon the line of Nurlu. On the evening of September 4 its long term of hard and glorious service was ended and the Twelfth Division took its place. Its losses had been 2700, while it had captured during the battle some 1800 prisoners and many guns.

From this date until September 10, which saw them in front of the outposts of the Hindenburg Line, the record of the Third Corps was one of steady and uninterrupted progress. The German machine-guns were now, as always, a cause of constant worry, loss, and delay, but the remorseless drive of the British infantry was for ever beating in the obstinate rearguards. September 6 marked an advance of nearly three miles along the whole Corps front, the Twelfth, Forty-seventh, and Seventy-fourth moving in line and flooding over the village sites of Nurlu, Templeux, Driencourt, and Longavesnes. The work of Owen’s 35th Brigade at Nurlu was particularly trying, for it was held up by wire and machine-guns, the 7th Sussex, 7th Norfolks, and 9th Essex all losing heavily in some very desperate fighting which gave little result. Finally, on September 6, the 1st Cambridge and 5th Berkshires reinforced the troops already mentioned and, under a renewed barrage, they broke the line and carried the position. On this date the Forty-seventh Londoners, who had done such solid work, were ordered off to join another corps, the Fifty-eighth moving up once more to take their place.

On September 7 the weather, which had been excellent since August 22, broke badly, but the Corps improved its position in spite of wind and rain, closing up to what was known to be the German fixed position. On the 8th both Epéhy and Peizières were touched, but the Germans were fairly at bay now, and instant counter-attacks showed that their resistance would be serious. The final position was about 1000 yards west of these villages. The Fifty-eighth Division on September 10 endeavoured to gain more ground in this quarter, but neither they nor the Seventy-fourth upon their right could make any impression upon the strong German line. There was a definite pause, therefore, while tanks, guns, and all other appliances for a serious assault upon a fortified position were hurried to the front. On this date, September 12, General Butler was able to resume his command of the Third Corps, while General Godley, after his term of brilliant service, returned to his own unit, the Twenty-second Corps.

We must now return to the Australian Corps on the right, whom we left in the flush of victory after their fine conquest of Peronne. Up to the end of August, Monash and his men had accounted for 14,500 prisoners and 170 guns since the beginning of the advance. On September 1, as already mentioned, Peronne had been penetrated by the Fifth Australian Division, but after the fall of Mont St. Quentin, and the failure of their efforts at recovery, the Germans must have seen that it was hopeless to hold the place, so that the stormers were eventually only faced by a rearguard of stalwarts. Anvil Wood to the north-east was taken on the same day. The order of the Divisions upon the Australian front at this time was that the Third was on the extreme left, acting with the Third Corps, the Second was just north of Peronne, the Fifth was opposite to Peronne, and the Thirty-second British Division was on the extreme right, near Brie and St. Christ, in touch with the French.

Early in the morning of September 2 Rosenthal’s indefatigable Second Division continued to advance from Mont St. Quentin, attacking to the north-east so as to get possession of the high ground south-west of Aizecourt. They attained their objectives and formed a flank along the spur from Mont St. Quentin to Aizecourt in order to protect the Third Corps in the difficult operations already described. By this movement to the north the Second Australian got in front of the Third Australian Division, which was crowded out of the line, all but two battalions. The Fifth Australians spent the day in clearing up Peronne. Altogether some 500 additional prisoners fell into their hands during the day.

There was some readjustment and reorganisation necessary after this strenuous work, but by September 5 the advance was going forward again and Flamicourt was taken. It is an open rolling country of large horizons, and the Germans were slowly retreating with strong rearguards. Doingt, Le Mesnil, and the river crossings of Brie and St. Christ were all occupied, though the latter cost a severe fight, with 150 prisoners as trophies. On the 6th and 7th the Corps were sweeping on with their own 13th Australian Light Horse doing the cavalry work in front of them, fit representatives of those splendid horsemen who have left an enduring reputation in Egypt and Palestine. Late in the afternoon of September 7 the Corps front crossed the railway between Vermand and Vendelles, and began to approach the historic point which had marked the British line before March 21. On September 10 Strickland’s First British Division arrived in this area, and with the Thirty-second Division and some other units began to form the nucleus of another Corps, the Ninth, which should operate under General Braithwaite to the right of the Australians. On the 12th the Australians took Jean-court, and were in touch with the outlying defences of the great Hindenburg Line, which they at once proceeded to attack. On September 13 there was a sharp fight round Le Verguier, and an advance all along the line in which the objectives were taken and the tanks did some particularly fine work. Tanks and barrages that day combined to keep the Australian losses at a very low figure, and yet some 40 guns and 4500 prisoners had been taken before next morning. The First Australian Division on the left secured all the front defences which guarded the main Hindenburg position, while the Fourth on the right worked its way well forward, though hardly level with its neighbours. The Ninth Corps on the right had also come on, though it was also rather behind the Australians. The average advance of the latter amounted to three miles in depth on a four-mile front.

Nothing could be more in-and-out than the German fighting during all this stage of the war. Sometimes their conduct was heroic in the extreme, sometimes it was exceedingly cowardly and slack. The observer could not but recall the famous description which an American General of old gave of his militia when he said with native raciness that “they either fought like the devil or ran like hell.” The machine-gunners were usually, however, in the former category, and they, with the heavy guns, represented the real resistance, while the infantry only needed to be reached—in some cases not even that—to throw up their hands and come over as joyful captives. There were already two Germans in British hands for every Briton in Germany, in spite of the heavy losses in March and April.

Returning to the Third Corps, which we left in front of the Hindenburg system in the second week of September in the Epéhy district. The obstacle in front of the British was very formidable, for it con, sisted of their own old trench lines of March, with the Hindenburg system behind them. They had now reached the former British reserve line which had Ronssoy, Lempire, Epéhy, and Peizières as points d’appui. It was a front so strong that in March it is doubtful if the Germans could have carried it had the line not given way elsewhere. It was particularly necessary that the enemy should hold on to this stretch, because it covered the point where the great Canal du Nord ran under a tunnel for six miles between Bellicourt and Vandhuile—the only place where tanks could be used for an advance. The Germans had therefore massed strong forces here, including their famous Alpine Corps.

The first task of the Third Corps was to get possession of the old British line in front of it, whence observation could be got of the Hindenburg position. This attack would form part of a general movement by the two southern Corps of the Third Army, the three Corps of the Fourth Army, and the northern portion of the First French Army. On that great day of battle, September 18, there was a universal advance along the line, which was carried out in the case of the Third Corps by the Seventy-fourth Division (Girdwood) on the right, the Eighteenth (Lee) right centre, the Twelfth (Higginson) left centre, and the Fifty-eighth Division left. Many of the characteristics of old trench warfare had come back into the battle, which was no longer open fighting, but is to be conceived as an attack upon innumerable scattered trenches and posts very strongly held by the Germans, and their ultimate reduction by independent platoons and companies acting under their own regimental officers.

The advance was at 5.20 in the morning, with a thick mist and driving rain to cover, and also to confuse, the movement. The Yeomen of the Seventy-fourth upon the right came away in excellent style, keeping in close touch with the Australian left, and were soon in possession of the Templeux quarries, a very formidable position. At the other end of the line a brigade of the Fifty-eighth Londoners did excellently well, and by 10 o’clock had a good grip upon the village of Peizières. In the centre, however, the resistance was very stiff and the losses heavy. None the less the Eighteenth Division, which has always been a particularly difficult unit to stop, made their way through Ronssoy and Lempire. The Eighteenth Division did wonderful work that day, and though nominally only the 54th and 55th Brigades were engaged, they were each strengthened by a battalion from the spare brigade. There were particular difficulties in the path of the 55th Brigade, but General Wood personally accompanied the leading battalion and so kept in touch with the situation, varying his activities by throwing bricks and old boots down a German dug-out, and so bringing out 20 prisoners as his own personal take. He was wounded in the course of the day. Ronssoy, which fell to the 55th Brigade, was held by the Alexander Regiment of Prussian Guards, several hundred samples being taken for the British cages. The taking of Lempire, carried out mainly by the 11th Royal Fusiliers, was also a very gallant affair, though it was a day or two before it was completely in British possession. The Twelfth; which is also an all-English division with a splendid fighting record, was held for a time before Epéhy, but would take no denial, and after heavy losses and severe fighting was east of that village by 11 o’clock. Thus by midday the whole line of villages was in the hands of General Butler’s Corps. The left was out of touch with the Fifth Corps, but all else was in perfect order. These positions were full of wire and concrete, and were defended by the hardy German Alpine Corps who fought to the death, so that the achievement was a great one.

All four divisions endeavoured to improve their positions in the afternoon, but they had no great success. The Seventy-fourth Division did the best, as on the right it was able to secure Benjamin’s Post, but on the left it was held up by the general stagnation of the line. The centre divisions met a German counter-attack delivered by the Hundred and twenty-first Division, who had been rushed up in buses from Maretz, and this they entirely dispersed, but neither they nor the Fifty-eighth on the left were able to make any notable advance.

The troops were now faced by a perfect warren of trenches and posts which were held with great gallantry by the Alpine Corps. There was no rest for the British, and the night of the 18/19th was spent by the same men who had been fighting all day in bombing up the trenches and endeavouring to enlarge their gains. The same sort of fighting, carried on by small groups of determined men led by subalterns or non-commissioned officers, and faced by other small groups equally determined, went on along the whole line during September 19 and 20. In those two days the advance went steadily on, in spite of many a local rebuff and many a temporary check. On September 21 the battle was renewed still in the same fashion with heavy losses upon both sides. At one time the steady flow of the British tide turned for a time to an ebb, as a very strong German counter-attack came rolling into it, and swept it back along the whole front from the positions which it had overflowed in the morning. The Seventy-fourth was forced out of Quinnemont Farm, the Eighteenth out of Doleful Post, the Twelfth were checked at Bird Trench, while the Fifty-eighth, intermingled with men from the right wing of the Fifth Corps, could not get past Kildare Avenue. These fanciful names, unseen on any save a large-scale trench map, bulked large in this bloody battle, for they were master points which controlled the ground around. The sun set with the Germans in the ascendant, and the British clawing desperately at a series of posts and farms which they could just hold against very heavy pressure. One of the most severe engagements was that of the 10th Essex of the 53rd Brigade when they attempted the Knoll, a position from which the whole Hindenburg Line would have been exposed. It was said by experienced soldiers that more severe machine-gun fire had seldom been seen than on this occasion, and the tanks engaged were unable to use their own guns, so thick were the driving storms of bullets which beat upon their iron sides and searched every aperture. The Essex men lost heavily, and the Knoll was not taken. This and the other posts mentioned above were the cause of much trouble to the Americans on September 27.

It was a disappointing day, but the British soldiers, dog-weary as they were, were in no mood to leave matters undecided. The operations must be carried to a successful end. “Hard pounding, gentlemen,” as the great Duke said, “but we shall see who can pound longest!” Just after midnight the tired ranks were stumbling forward once more, determined to have those posts back if human resolution could win them. They had their reward, and it was a conspicuous illustration of the maxim that, however weary you may be, the enemy may be even more so. Before the full light of morning half the line of posts was in the hands of the persevering British. The capture of Bracton Post by Colonel Dawson’s 6th West Kents was a particularly brilliant bit of work. The success stretched along the whole Corps front, and though the afternoon of September 22 saw a whole series of counter-attacks, especially upon the Seventy-fourth and Eighteenth Divisions, there was no weakening of the new line. One German battalion engaged in these counter-attacks was literally annihilated as a barrage fell behind them through which they could not retire. It is on record that in spite of the very arduous service the spirits and morale of the men were never higher. Twice after a German repulse the men of the 6th Northants and 11th Royal Fusiliers could not be held back from jumping out of the trenches and tearing after them, while a stretcher-bearer was observed to run up and down the parados of the trench throwing cartridges down to the defenders and shouting, “Shoot, boys, shoot!”

By September 23 the Third Corps had gained most of those posts which had been its objectives on September 18, and if the battle took longer than had been anticipated it was all the greater drain upon the worn resources of the Germans. They were still intent upon making machines do the work of men, and it was no unusual thing to take about as many machine-guns as prisoners in some of their posts. The situation was still not quite clear on the left, where the right flank of the Fifth Corps was engaged in severe local fighting in the neighbourhood of Kildare and Limerick Post. The Egg Post on the front of the Eighteenth Division had also been able to maintain itself in the German line. These various isolated strong points were the same which had held out with such unavailing gallantry on March 21, when, instead of forming the German rear, they were the extreme outliers of Gough’s Army.

Whilst the Third Corps on the left of the Fourth Army had been gradually fighting its way forward from September 18 onwards, beating down one after the other the outposts and obstacles which, like the moraine before a glacier, formed a rugged line in front of the great main Hindenburg system, Sir John Monash and his men were keeping pace with them, step by step, on their right, the First Australian Division being in close liaison on September 18 with the Seventy-fourth Yeomanry. Many a separate volume will be written upon the exploits of our Australian brothers, and General Monash has himself written a record of their last glorious hundred days, so that the chronicler has the less compunction if he is not always able to give the amount of detail which he would desire.

At 5.20 on September 18 the Australians went forward with a rapidity which seems to have completely taken aback the German defenders, who in many cases ran from their guns, or threw up their hands in detachments, when they saw the active figures of the infantrymen springing eagerly forward behind the line of tanks. The weather was bad, the ground slippery with rain, and the attack expected, but none of these factors interfered with the result. The First Australians, as stated, were in the line on the left, the 1st and 3rd Brigades in the van, while on the right were the 4th and 12th Brigades of the Fourth Australian Division in close touch with the British First Division on their right. By midday everything had gone down before them, and the measure of their success was the 146 officers and 3900 men with 77 guns which formed their trophies before evening. On one side they had reached Le Verguier, and on the other they were past Templeux. A minefield containing thirty-five mines was found in front of the Fourth Australian Division, another instance of the fact that the tanks had brought a nautical element into warfare. The Australian casualties were surprisingly light considering their splendid results, for they did not amount to more than a thousand men.

Some description must now be given of the work of the Ninth Corps, which had assembled under General Braithwaite on the extreme right of the British Army and which first came into action on September 18 in this hard fight for the Hindenburg Outpost Line. The Corps consisted at this time of three divisions, the First, Sixth, and Thirty-second, under Strickland, Marden, and Lambert. On September 18 the Corps attacked with the Sixth Division in touch with the French on the right, and the First Division with the Fourth Australians on the left. The order of brigades from the right was 71, 16, 1, and 2. It was known that two German divisions, the Seventy-ninth and Twenty-fifth, with two others in reserve, were lying opposite behind strong defences, so that a hard battle might well be expected.

The Thirty-fourth French Division on the immediate right brought off a very useful and successful coup on September 17 by capturing Round Hill and part of Savy Wood, which reassured General Marden as to the safety of his right flank. This division appeared to have the more difficult task as Badger Copse, the village of Fresnoy, and part of the very strong system known as the Quadrilateral came within their area.

The attack went forward under pelting rain at 5.20 in the morning of September 18. Following the operations from the north we have to deal first with the 2nd Brigade on the flank. The left-hand battalion; the 2nd Sussex, kept up with the Australians, who had advanced without a check and carried every obstacle. The 2nd King’s Royal Rifles, on the other hand, had lost direction and, wandering too far south across the face of their neighbours, found themselves mixed up with the Sixth Division in its fruitless attempt upon the powerfully defended village of Fresnoy. The 1st Brigade, to the south, was led by the 1st Camerons and the 1st Loyal North Lancashires. The former stormed on, breaking through all opposition and throwing out defensive flanks as their valour carried them ahead of the line. Meanwhile the failure of the Sixth Division to take Fresnoy made it impossible to pass along the valley which is overlooked by that village, so that the right of the First Division was entirely hung up. On the other hand, the 2nd King’s Royal Rifles recovered their bearings as the day went on, and fought their way up the right side of the Omignon valley in splendid style until they were in touch with the 2nd Sussex on the northern slope. In the south, however, the task of the Sixth Division continued to be a very hard one, and the Seventy-ninth German Division resisted with great determination. The Quadrilateral consisted of a system of trenches sited on the highest part of the plateau between Holnon and Fayet, its northern face at this time forming part of the German front line. This proved to be an exceedingly difficult work to silence, as reinforcements could be dribbled up through cleverly concealed communication trenches. In spite of everything; however, the 71st Brigade and their French neighbours captured Holnon village and the western edge of the Quadrilateral by 8 A.M. The main body of the work was not yet taken, however, so the East Anglians of the 71st Brigade had to form a defensive line facing towards it and the village of Selency, to meet any counter-attack which might sweep up against the flank of the Corps. The left of the line then got forward in safety, and the 2nd Brigade was able to report at noon that both they and the Fourth Australians were on their extreme objective. Indeed the latter, having completely crumpled up the One hundred and nineteenth German Division, were now considerably ahead of the allotted line.

Berthaucourt had been captured by the First Division, but progress in the Fresnoy direction was still very slow. About 3.30 P.M. hostile counter-attacks were launched south of Berthaucourt and opposite Fresnoy. These were repulsed by steady rifle-fire, but the general situation was still obscure. All the afternoon there was very heavy fighting on the front of the Sixth Division, especially east of Holnon village, and on the west side of the Quadrilateral. The French had been held up on the right. So matters remained until evening. It had been a day of hard work and varying success on this portion of the line, but the capture of 18 officers and 541 men with 8 field-guns showed that some advance had been made. It was short, however, of what had been hoped.

The next morning saw the battle renewed. The neighbourhood of Fresnoy and of the Quadrilateral was now more strongly held than ever, the Germans being encouraged, no doubt, by their successful defence of the day before. The fighting during this day was desultory, and no particular advance was made by either division. In the south the French failed to capture Manchester Hill, which was an ugly menace to the right flank of the Ninth Corps.

The Forty-sixth Division (Boyd) had been added to the strength of the Ninth Corps, and when this welcome addition had been put in upon the left wing it enabled the others to contract their front and thicken their array. At 7 P.M. on September 22 the Germans attacked the Forty-sixth Division in its new position, just east of Berthaucourt, but they were driven back after a slight initial success.

There was a fresh attack on September 24 in which the Ninth Corps co-operated with the Thirty-sixth Corps on its right, in order to try and overcome the German strongholds on the right of their front which were holding them of from the Hindenburg Line. The order of the British line was that the Sixth Division was on the right, the First in the centre, and the Forty-sixth on the left.

Although this attack, which was launched at 5 A.M., was expected by the enemy, good progress was made along the whole front. The Quadrilateral again proved, however, that it was a very formidable obstacle, and there was stout resistance from Pontruet village, just east of Berthaucourt. The Sixth Division had closed in on the Quadrilateral from north, west, and south, and were at close grips with it at all three quarters. There was continuous bomb-fighting all day in this neighbourhood, but the situation was still obscure, and until it cleared no progress could be made towards Selency. The First Division in the centre had made splendid progress, but the Forty-sixth Division had been unable to take Pontruet, and the guns from this village struck full against the left flank of the 2nd Brigade in its advance, causing very heavy losses to the 1st Northamptons. So murderous were the casualties in this portion of the field that the position of the forward troops was untenable, and the remains of the Northamptons had to throw back a protective flank to the north to cover the approaches from Pontruet. The 2nd Sussex on their right managed to retain their advanced position, and one company, though very weak and short of cartridges, baffled a counter-attack by a sudden bayonet charge in which they took 50 prisoners.

The attack upon Fresnoy village was made by the 3rd Brigade, the 1st Gloucesters being immediately opposite to it. Advancing under a strong barrage the West Country men went straight for their objective, taking both the village and the strongly organised cemetery to the south of it. On the left of the village the British were held up by strong wire and several vicious machine-guns, but the Germans made the gallant mistake of running out in front of the wire with bombs in their hands, upon which they were charged and many of them were taken by the Gloucesters. The German gunners in the rear then turned their pieces upon both captors and captives, so the company concerned was held down in shell holes all day and withdrew as best they could after dark. The 3rd Brigade then extended, getting into touch with the 2nd Brigade near Cornovillers Wood.

On the left of the 3rd Brigade the strong position of Fresnoy Cemetery had been carried, and the tireless infantry swarmed on into Marronnières Wood, which was full of lurking machine-guns and needed careful handling. It was finally surrounded by the 3rd Brigade, who mopped it up at their leisure, taking out of it a large number of prisoners. The 2nd King’s Royal Rifles of the 2nd Brigade kept parallel with their advance, and also cleared a considerable stretch of woodland, while the 3rd Brigade, seeing signs of weakening on the German front, pushed forward and seized Gricourt, a most important point, the 2nd Welsh gaining the village and driving back a subsequent counter-attack. Finally, the complete victory in this portion of the field was rounded off when, after dark, the 2nd King’s Royal Rifles secured a dangerous sunken road across the front which had been a storm-centre all day.

Meanwhile the Forty-sixth Division had fought its way to the north of Pontruet, but as this unit was relied upon for the great pending operations on the Hindenburg Main Line, it was thought impolitic to involve it too deeply in local fighting. The line was drawn, therefore, to the west of the village. The total captures of the day had been 30 officers and 1300 men. The French to the south had also had a good day, capturing all their objectives except Manchester Hill.

The Sixth Division had not yet cleared the Quadrilateral, and the whole of September 25 was devoted to that desperate but necessary work. It was a case of bomb and bayonet, with slow laborious progress. Finally, about 6 P.M. General Marden was able to announce that the whole wide entanglement had been occupied, though not yet mopped up. The village of Selency had also fallen, while on the right the French had attacked and captured Manchester Hill. Strong resistance was encountered by the First Division near Gricourt. The German soldiers were again and again seen to hold up their hands, and then to be driven into the fight once more by their officers with their revolvers. Late on the 26th, after a short hurricane bombardment, the 3rd Brigade rushed forward again. The enemy had disappeared into their dug-outs under the stress of the shells, so that the British infantry were able to get on to them before they could emerge and to make many prisoners. Colonel Tweedie of the Gloucesters was in local command of this well-managed affair. Altogether it was a good day for the First Division, which had gained a line of positions, repelled heavy counters, and secured 800 prisoners, 600 falling to the 3rd Brigade, who had done the heavy end of the work.

All was now ready for the great move which should break the spine of the whole German resistance. There was still some preliminary struggling for positions of departure and final readjustments of the line, but they were all part of the great decisive operation of September 29 and may best be included in that account. The chronicler can never forget how, late upon the eve of the battle, he drove in a darkened motor along pitch-black roads across the rear of the Army, and saw the whole eastern heaven flickering with war light as far as the eyes could see, as the aurora rises and falls in the northern sky. So terrific was the spectacle that the image of the Day of Judgment rose involuntarily to his mind. It was indeed the day of Judgment for Germany—the day when all those boastful words and wicked thoughts and arrogant actions were to meet their fit reward, and the wrong-doers to be humbled in the dust. On that day Germany’s last faint hope was shattered, and every day after was but a nearer approach to that pit which had been dug for her by her diplomatists, her journalists, her professors, her junkers, and all the vile, noisy crew who had brought this supreme cataclysm upon the world.

The reader will note then that we leave the Fourth Army, consisting from the right of the Ninth Corps, the Australians, and the Third Corps, in front of the terrific barrier of the main Hindenburg Line. We shall now hark back and follow the advance of Byng’s Third Army from its attack on August 21st until, five weeks later, it found itself in front of the same position, carrying on the line of its comrades in the south.

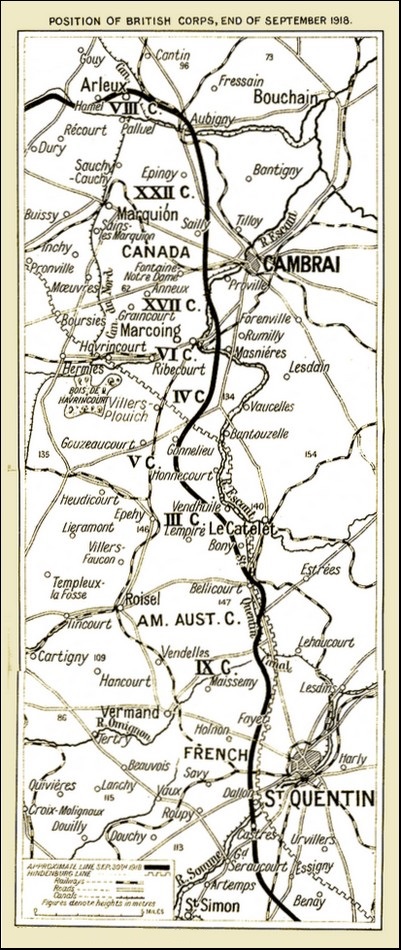

Position of British Corps, end of September 1918