IV. The Attack of Byng’s Third Army

August 21, 1918, to September 29, 1918

Advance of Shute’s Fifth Corps—Great feat in crossing the Ancre—Across the old battlefield—Final position of Fifth Corps opposite Hindenburg’s Main Line—Advance of Haldane’s Sixth Corps—Severe fighting—Arrival of Fifty-second Division—Formation of Fergusson’s Seventeenth Corps—Recapture of Havrincourt—Advance of Harper’s Fourth Corps—Great tenacity of the troops—The New Zealanders and the Jaeger—Final position before the decisive battle.

On August 20 General Mangin had pushed forward the Tenth French Army, which formed the left of his force, and attacked along a sixteen-mile front from the Oise to the Aisne, thus connecting up the original operations with those initiated by Marshal Haig. The movement was very successful, taking some 10,000 prisoners and gaining several miles of ground. We have now to turn to the left of Rawlinson’s advance, and to consider the new movement which brought Byng’s Third British Army into the fray.

Upon the left of the Third Corps, which was, as already described, fighting its way along the north bank of the Somme, there lay the Fifth Corps (Shute). On its left was the Fourth Corps (Harper), and north of that the Sixth Corps (Haldane). It was to these three units that the opening of the attack was entrusted. The frontage was about ten miles, extending from Moyenneville in the north to the Ancre in the south, so that it just cleared the impossible country of the first Somme battlefield—which even now a spectator cannot survey without a feeling of wondering horror, so churned up is it from end to end by the constant thresh of shells, burst of mines, and the spade-work of three great armies. The result of the first day’s fighting was an advance of several miles along the whole front, with the capture of Beaucourt, Bucquoy, Moyenneville, and other villages, the farthest advance coming close to the Arras-Albert Railway, and to the village of Achiet-le-Grand.

There had been some recent retirement of the German line at Serre, which gave the clue to the British Commanders that a general retreat might take place on this particular portion of the front. It was very necessary, therefore, to strike at once while there was certainly something solid to strike against—and all the more necessary if there was a chance of catching the enemy in the act of an uncompleted withdrawal.

It was nearly five o’clock when the battle began, and it was the turn of the Germans to find how fog may disarrange the most elaborate preparations for defence. The mist was so thick that it could only be compared to that which had shrouded the German advance on March 21. Several miles of undulating country lay immediately in front of the attackers, leading up to a formidable line of defence, the old Albert-Arras Railway lying with its fortified embankments right across the path of the British Army. Bucquoy in the centre of the line, with the Logeast Wood to the east of it, and the muddy, sluggish Ancre with its marshy banks on the extreme right, were notable features in the ground to be assaulted.

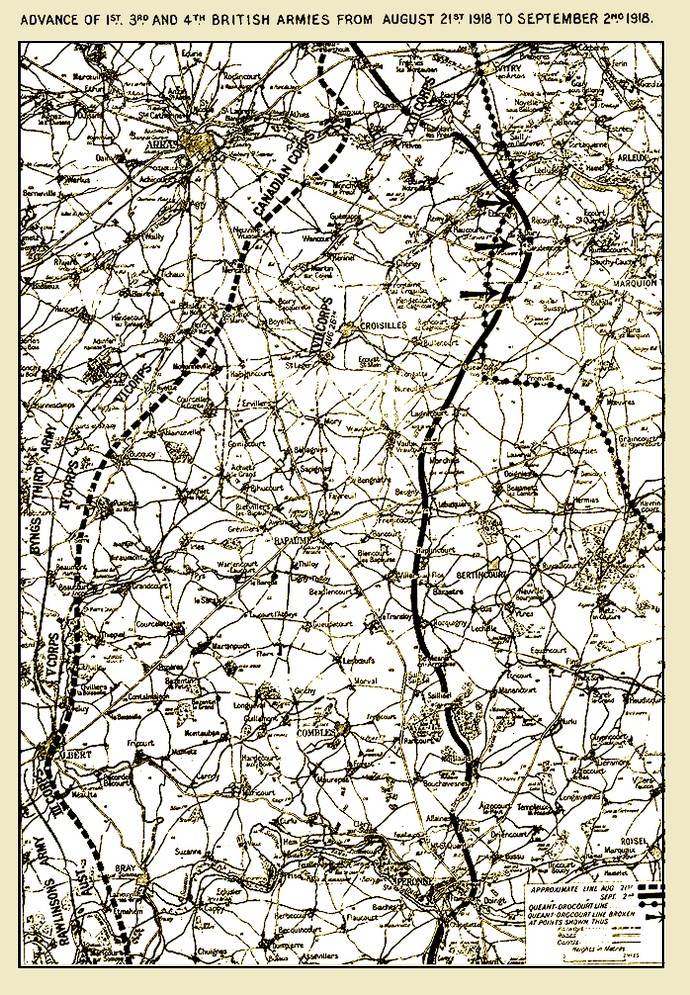

Advance of First, Third, and Fourth British Armies from August 21, 1918, to September 2, 1918.

Arrows point to the Rupture of the Quéant-Drocourt Line.

The Fifth Corps, under General Shute, followed the curve of the River Ancre on a front of 9000 yards. It was poorly provided with guns as the Corps to the left required a concentration of artillery, and it had no tanks since the marshy valley and sluggish stream lay before it. The Thirty-eighth Welsh Division (Cubitt) lay on the right and Campbell’s Twenty-first on the left, each of them with two brigades in front and one in reserve. The Seventeenth Division (Robertson) was in support. The problem in front of General Shute’s Corps was a most difficult one. Before it lay this evil watercourse which had been flooded by the Germans and was 300 yards wide at one part. All bridges were gone, and the banks were low and boggy. The main stream was over six feet deep, and its channel could not be distinguished from the general flood. The whole morass was covered by a tangle of fallen trees, reeds, and artificial obstructions. To the east of the river ran high ground, strongly held and fortified, from Tara Hill above Albert to the Thiepval Height, south of Grandcourt. The west bank was so overlooked that no one could move unscathed. And yet it was clear that until this formidable obstacle was surmounted it was neither possible for Rawlinson to advance from Albert, nor for the Fourth Corps on the left to assault Miraumont.

The movements of Shute’s Corps on August 21 were preliminary to their real attack. On that date the Twenty-first Division advanced on the left flank, in close touch with the Forty-second Division of the Fourth Corps. Beaucourt was taken in the movement. By this operation the Twenty-first Division reached a point where the flood was narrower at St. Pierre Divion, and here some bridges could be constructed and preparations made for the passage.

In the case of Harper’s Fourth Corps on the left the advance on August 21 was limited, since no serious attack could be made upon Miraumont while the high ground to the south was untaken. At this date Harper’s Corps consisted of five divisions, the Fifth, Thirty-seventh, Forty-second, Sixty-third, and the New Zealanders. Of these the Thirty-seventh Division (Williams) was on the left, covering the flank of the Sixth Corps, while the Forty-second (Solly-Flood) was on the right. We shall now follow in the first instance the work of the Fifth Corps on the extreme right from the beginning of the battle until the pause preceding the attack of September 18. There are, it is true, objections to continuous narrative, since it stands in the way of a bird’s-eye view of the whole operation; but on the other hand the object and scope of any series of advances become unintelligible unless they are linked up from day to day. We shall therefore take the Fifth Corps as one story until it reaches the Hindenburg Line. We shall then follow the work of the other flank corps of Byng’s Third Army, which was Haldane’s Sixth Corps, bringing it up to the same point. It will finally, after we have established two solid bastions, be easy to deal with the central unit, Harper’s Fourth Corps, which filled up the space between. We shall then have a narrative which will cover four strenuous weeks in which the Third Army carried out a notable advance.

It has been explained that Shute’s Fifth Corps found itself with 9000 yards of river in front of it, and that on August 21 the Twenty-first Division had seized a favourable point for crossing near St. Pierre Divion. There was no further advance on the morning of the 22nd, but to the south Rawlinson’s left was fighting its way to the eastern exits of Albert, and the bridges in the town were being got ready for use. All day a heavy fire was kept up on the German lines east of the river, and especially upon the rising ground called Usna Hill. As the day passed small bodies of troops began to cross the Ancre from the Fifth Corps front and to make a lodgement at the farther side. South-west of Thiepval part of the 14th Welsh from the 114th Brigade, wading over breast deep with their rifles and pouches held high, got into a trench on the farther bank and held their own. The Twenty-first Division also got some companies across at St. Pierre, while it beat off several attacks upon the north side of the river. During the night the 50th Brigade of the Seventeenth Division was slipped into the line, between Campbell’s North Countrymen on the left and Cubitt’s Welshmen on the right. General Shute was now ready for his great effort in crossing the river.

The first stage in this difficult operation was carried out early on August 23, when the 113th Welsh Brigade, which had quickly passed over the Albert bridges, made a sudden attack about dawn on Usna Hill, at the same time as the Eighteenth Division to the south attacked Tara Hill. The position was taken with 200 prisoners, while the 115th Welsh Brigade got up to the chalk-pit, east of Aveluy, where they joined hands with their comrades on the Usna line. Thus, before evening of August 23 the Thirty-eighth Division was east of the river from Albert to Aveluy, while the Twenty-first still held its bridgeheads at St. Pierre Divion. The slope of the Thiepval Ridge with all its fortifications still lay in front, and this was the next objective of the Fifth Corps. It was carried by a night attack on August 23-24.

A large portion of the central line was so flooded that no advance was possible. It was planned, therefore, that the assault should be on both wings, the area around Authuille being nipped out and cleared at a later stage. The operation began on the evening of August 23 by a movement along the northern bank of the river to the south-east of Miraumont, so as to partly encircle that village and help forward the Fourth Corps on the left, who were still held up in front of it. The main Ancre attack was carried out by the 113th Brigade on the right, who came away with a fine impetus on the eastern slopes of Usna Hill, capturing La Boiselle and reaching a point 1100 yards west of Ovillers. The 114th Brigade on the left had with great difficulty and corresponding valour crossed the Ancre under machine-gun fire and had established themselves on the slopes, fighting their way forward all day until they reached a point north-west of Pozières. All around Thiepval there was close fighting in which this brigade acted in close liaison with the 50th Brigade. In this struggle many gallant deeds were done, and it is recorded, among others, how Lieutenant Griffiths of the Welsh Regiment advanced using his Lewis gun as if it were a rifle. He is said to have slain sixteen Germans in this novel fashion before his own wounds brought him fainting to the ground. According to the plan the two converging brigades left a large central section untouched, which was promptly mopped up by the 115th Brigade, so that every man of the Thirty-eighth Division was engaged in this fine operation.

Farther to the left the 6th Dorsets of the 50th Brigade, in spite of gas clouds and machine-guns had crossed the Ancre in its narrowest reach, where some sort of bridges had been prepared. With great energy and initiative they cleared up the front trenches and pockets so as to give room for a deployment, pushing their patrols out towards Thiepval, but they were driven in again by an attack from the Schwaben Redoubt. The rest of the 50th Brigade (Gwyn-Thomas) had followed, most of the infantry wading across in the dark up to their waists in mud and water. Pushing on, as part of the general advance, all three battalions of the 50th Brigade went forward, capturing several hundred prisoners, but deviating so far from their course that when they thought and reported that they had captured Courcelette it was really Pozières which they had got. In the early afternoon Allason’s 52nd Brigade was pushed in on the right of the 50th Brigade, connecting them up with the Welshmen. The mistake in the direction of the 50th Brigade was not an unmixed evil, for while it left the Twenty-first Division with its right flank exposed and in considerable difficulty, it made a pocket of a large number of Germans in front of the Welshmen, 900 of whom were captured. General Robertson saved the situation on the left by pushing in his reserve brigade, the 51st (Dudgeon), and so filling the gap between his division and that of General Campbell.

The latter division, especially the 64th Brigade, which had pushed on to Miraumont the night before, had some desperate fighting. The whole brigade was passed in single file over two foot-bridges. At 11.30 P.M. they were assembled upon the south bank and ready to start. A barrage had been arranged for their attack, but owing to changes in plan it was not thick or effective. The advance was made by the 15th Durhams on the right and the 9th Yorkshire Light Infantry on the left with the 1st East Yorks in support, the column being guided by means of compass bearing, and by the presence of the Ancre on the left flank. This nocturnal march in the face of the enemy was a very remarkable and daring one, for the ground was pitted with craters and there were two ravines with sheer sides at right angles to the advance. Touch was kept by shouting, which seems to have confused rather than informed the enemy, who only fought in patches. Grandcourt was overrun with 100 prisoners, 20 machine-guns, and 4 field-pieces. Early in the morning General McCulloch, who had conducted the operation, was badly wounded and the command passed to Colonel Holroyd Smith of the Durhams. When full daylight came the brigade was deeply embedded in the German line, and the enemy closed in upon it but their attacks were repulsed. The soldiers were compelled to lie flat, however, in order to escape from the heavy fire. The 110th Brigade of the same division had advanced on the right, but it was acting in close liaison with the Seventeenth Division, and independent of the isolated unit, which was now completely alone on the hill south of Miraumont, their East Yorkshire supports being at Grandcourt, and so much out of touch with the advanced line that the Officer Commanding imagined the stragglers to be all that was left of the brigade. The first intimation of the true state of affairs was given by the wounded Brigadier as he passed on his way to the casualty station. About 10.30 Captain Spicer, the Brigade Major, got back by crawling, and reported that the advanced line still held, though weak in numbers. Aeroplane reconnaissance confirmed the report. All day the valiant band held out until in the evening the advance of the Forty-second Division on their left, and of their own comrades of the 110th Brigade on their right, rescued them from a desperate situation. Their work had been exceedingly useful, as their presence had partially paralysed the whole German system of defence. Great credit in this remarkable affair was due not only to General Campbell and his staff, upon whom the initial responsibility lay, but to the gallant and inspiring leading of General McCulloch and of the battalion leaders, Holroyd Smith and Greenwood. It was indeed a wonderful feat to advance three miles over such country upon a pitch-dark night and to reach and hold an objective which was outflanked on both sides by the successful German defence. The troops had been heartened up by messages with promises of speedy succour which were dropped by aeroplanes during the day.

The 62nd Brigade had now pushed in between the 64th on the right and the Forty-second Division on the left, touching the latter in the neighbourhood of Pys, so that by the late afternoon of August 24 the whole line was solid and the crossing of the Ancre with the capture of the ridge were accomplished facts. There have been few more deft pieces of work in the war. The German fixed line had been driven back and the remaining operations consisted from this date onwards in a pursuit rather than an attack. It was a pursuit, however, where the retreat was always covered by an obstinate rearguard, so that there was many a stiff fight in front of the Fifth Corps in the days to come.

Divisions had been instructed that the pursuit was to be continued in a relentless fashion, and Corps cavalry, drawn from the 8th and 20th Hussars, were told off to throw out patrols and keep in close touch with the German rearguard. The immediate objectives of the infantry were Longueval and Flers for the Welshmen, Gueudecourt for the Seventeenth, and Beaulencourt for the Twenty-first Division. The general movement was extraordinarily like the advance in the spring of 1917, but the British were now more aggressive and the Germans were less ‘Measured and sedate in their dispositions. On August 25 the pressure was sustained along the whole line, and the Germans, fighting hard with their machine-guns which swept the exposed ridges, were none the less being pushed eastwards the whole day. The Welsh took Contalmaison and reached the edge of Mametz Wood, where so many of their comrades had fallen just two years before. The Seventeenth, fighting hard, captured Courcelette and Martinpuich. The Twenty-first got Le Sars and the Butte de Warlencourt, that strange old tumulus which now marked the joining point with the Fourth Corps still advancing on the left. At no point was there a battle and at no point was there peace, but a constant ripple of fire rose and fell along the thin fluctuating line. It is noted in the diaries of some of the British Generals as being the first day of purely open warfare in offensive fighting which their troops had ever experienced.

On the morning of August 26 the Welsh overran Bazentin-le-Grand, but the 115th Brigade were held up for a time at the old stumbling-block High Wood. Later in the day it was taken, however, while the 113th Brigade got as far as the edge of Longueval, meeting, a severe counter-attack which was rolled back in ruin by rifles and machine-guns. The Seventeenth Division gained some ground, but both brigades, the 51st and 52nd, were held up by a withering fire before reaching Flers. The 64th Brigade on their left met with equal opposition and could not get forward. Everywhere there were signs of a strong German rally for the evident purpose of covering the removal of their guns and stores. It was well maintained and well organised, so that the object was attained. It became clearer with every day that an artillery barrage was still a necessity for an infantry advance.

On August 27 the advance was continued. Outside the Fifth Corps boundaries the Fourth Corps on the left was encircling Bapaume and pushing advanced guards on to Maplecourt and Frémicourt, while Rawlinson’s men on the right were facing Trones Wood and the Guillemont Ridge. In the early morning, with a moon shining brightly, the whole front of the Fifth Corps was on fire once more and rolling eastwards. By 9 A.M. the 113th Brigade were through Longueval and in touch with the Fourth Army near the Sugar Refinery. The 114th Brigade attempted to pass north of Delville Wood, but after some confused fighting were held on the line of the Flers—Longueval Road. Flers, however, had been taken by the 50th Brigade, though the Germans made a strong fight of it and at one time reoccupied the village. Whatever the general morale of the enemy may have been there was no immediate weakening in the actual fighting power of his line. The Twenty-first Division made only a moderate advance, but they got ahead of their neighbours. The 6th Dragoon Guards, who were now furnishing the patrols, were withdrawn, as it was clear that the Germans meant to stand.

On the morning of August 28 they were still in position, and the day was mainly devoted to reorganising the infantry and bombarding the German lines, together with all the roads which lay eastwards. Early next morning the Welsh advanced once more, the 113th Brigade on one side of Delville Wood and the 114th on the other, with the result that this sinister graveyard was surrounded and the line carried definitely to the east of it. Morval still held out, but Lesboeufs was overrun. There was weakening all along the German line, which meant no doubt that they had completed the withdrawal of their more essential impedimenta. Flers and Gueudecourt both fell to the Seventeenth Division, almost without a battle. The Twenty-first Division was also able to move forward with no great difficulty as far as Beaulencourt and the line of the road from that village to Bapaume. This new line was held with great determination by the enemy, who were still, as must be admitted, masters of the situation to the extent that though forced to retire they would still retire in their own fashion. The Welsh attacking Morval that night found the place was strongly held and no progress possible.

August 30 was to show that the German rearguards were by no means demoralised and were not to be unduly hustled. It is impossible not to admire the constancy in adversity of Hans and Fritz and Michel, whatever one may think of the mentality of the Vons who had placed them in this desperate position. Morval still held its own against the Welsh, and the Seventeenth Division could not reach the clear line in front of them which is furnished by the Peronne—Bapaume Road. Beaulencourt was also retained by the enemy, as the patrols discovered to their cost. The line was still strong and menacing. There was inaction on August 31, which was spent in bombardment and preparation.

At 2 A.M. on September 1 the Twenty-first Division attacked Beaulencourt and carried it with a rush, and a strong attempt to regain it after dawn cost the enemy heavy losses. During the morning the Welshmen on the right flank attacked Morval and were at last successful in taking this strong position. There was very heavy fighting all day round Sailly-Sallisel, where the 113th and 115th Welsh Brigades made repeated efforts to envelop and capture the village. There were several checks, but the gallant Welshmen stuck to their task, and before evening the place had fallen and the general British line was well to the east of it. On the other hand, the Seventeenth and Twenty-first Divisions had a bad day in front of Le Transloy and the Sugar Factory, having nothing to show for considerable losses, the 9th West Ridings being especially hard hit. None the less the Seventeenth was hard at it again next morning, for it was imperative to keep up the pressure without any relaxation. On this day, September 2, the plan was that the 50th and 52nd Brigades should work round on each side of the village while the artillery kept the defenders from interfering. This attack, though delayed for some time, eventually succeeded, the 6th Dorsets clearing up the ruins, while the Twenty-first Division, after several brave attempts, drove the tenacious German garrison out of the Sugar Factory. The 10th West Yorkshires, under Colonel Thomas, did particularly good work in linking up the two divisions. Altogether it was a very satisfactory morning’s work, and the 50th Brigade added to it in the evening by capturing in a fine attack the village of Rocquigny, and pushing patrols on into Barastre, which was found to be empty. On this day, as the Corps front had contracted, the Twenty-first Division was drawn back into reserve. It may be remarked that in all these operations Robertson’s Seventeenth Division had the supreme satisfaction of hurling the enemy out of a long series of villages which they had themselves been forced to relinquish under the pressure of the great March advance.

It was clear now that the Germans, either of their own will or driven by the constant pressure, were withdrawing their rearguards, so that in the early morning of September 3 no touch could be gained by patrols. By 6 A.M. the British advance guards were well on their way, streaming forward to the Canal du Nord, from the eastern bank of which the eternal machine-guns were rapping away once more, stopping the 50th Brigade in an attempt to make a direct advance. There were no bridges left, so nothing further could be done that day, which brought the corps front up to the western bank from Manancourt to the north-east of Etricourt. On September 4, however, the crossing was effected without any very great difficulty, and bridge-heads established by both the divisions in the line.

On September 5 the 114th Brigade attacked the trench system round Equancourt without success. The 51st Brigade had better luck to the north of the village and gained a good bit of ground. The 7th Lincolns were held up with considerable loss in the first advance on account of some misunderstanding about the starting-point and insufficient touch with the Forty-second Division on their left. The 7th Borders, a battalion made up of Cumberland and Westmoreland Yeomanry, carried on the attack and found the village deserted. The day ended with the right flank of the Fifth Corps in touch with the Third Corps to the north-west of Nurlu, while the left flank joined the Fourth Corps north of Vallulart Wood. That night the Twenty-first Division came back into line, taking the place of the Welshmen who had done such splendid and strenuous service since August 22.

September 6 and 7 were occupied in a slow but steady advance which absorbed Equancourt, Fins, and Sorel-le-Grand. On September 8 matters were less one-sided, as the Twenty-first Division, acting in close liaison with Rawlinson at Peizières, attacked Vaucelette Farm and Chapel Crossing. It must have been with peculiar ardour and joy that General Campbell and his men flung themselves upon the positions which they had held so heroically upon March 21. Here after six months were their complete vindication and revenge. The fighting was carried on into September 9, the Seventeenth Division joining in on the left in close touch with the New Zealanders of the Fourth Corps. It was clear that the Germans meant standing if they could and the struggle was a very hard one, but before evening much of the ground had reverted to the two divisions which were both, by a peculiar coincidence, more or less in their old positions. There were attack and counter-attack, and a good price paid for all that was gained. There are days when land is cheap and days when it is the dearest thing upon earth. At the end of this fight the Germans were in a continuous trench on one side of the ridge and the British in a corresponding position on the other. It became more and more clear that the days of pursuit and rearguard actions were over, and that the whole British front in this quarter was up against a fixed battle position of the enemy—or at the least against the strong outposts in front of a fixed battle position. This important fact regulates the whole situation up to the great attack of September 29.

September 10 and 11 were spent in local encounters in the Chapel Crossing and Vaucelette Farm district, the Germans striving hard by these outpost engagements to prevent the British line from getting within striking distance of the old Hindenburg position, behind which they hoped to rally their dishevelled forces. The British were equally eager to break down this screen and get at the solid proposition behind it. The weather was terrible, rising at one time to the height of a cyclone, which disarranged the assembly. On September 12 there was a more serious British advance, the Fourth Corps on the left attacking the Trescault Spur, while the Welsh, who had now relieved the Seventeenth Division, were to go forward on their flank. The Germans clung desperately to their ground, however, and after a long day of alternate advance and retreat the British line was where it had been in the morning. A position called African Trench lay in front of the Welshmen, and it was not possible to carry it in face of the very severe machine-gun fire. From this date until September 18 there was no advance and no change on the front of the Fifth Corps save that Pinney’s Thirty-third Division came in to patch its worn array.

On September 18 the Fifth Corps attacked once more in conjunction with Rawlinson’s Army on its right, the final objective being the trench lines south of Villers-Guislain—Gauche Wood. The advance was made by the Welsh Division opposite to Gouzeaucourt, the Seventeenth in front of Gauche Wood, and the Twenty-first to the immediate south. It was preceded by field barrage, heavy barrage, machine barrage, trench mortar bombardment, and every refinement of artillery practice as elaborated in this long war. The results of a hard day’s fighting were rather mixed. The Welsh Division was held near Gouzeaucourt and finished up in its own original line, leaving the left flank of the 52nd Brigade exposed. The two other divisions were able, after hard fighting, to reach their objectives, including Gauche Wood. The Twenty-first Division had a particularly trying and yet successful day, all three brigades being heavily engaged and enduring considerable losses in capturing the very ground which they had held on March 21. Their advance was complicated by a mine-field, laid down by themselves and so well laid that it was still in a very sensitive condition, while the dug-outs had been so undisturbed that the 1st Lincolns actually found their own orderly papers upon the table. In the fighting the 62nd Brigade led the way with complete success, and it was not until the 64th and the 110th Brigades passed through it and began to debouch over the old No Man’s Land that the losses became serious, Epéhy and Peizières being thorns in their flesh. Colonel Holroyd Smith of the 15th Durhams was killed, but the 64th Brigade made good its full objective, the 1st East Yorks capturing a German howitzer battery, together with the horses which had just been hooked in. At one time the Germans got round the left flank of the Division and the situation was awkward, but Colonel Walsh of the 9th Yorks Light Infantry, with his H.Q. Staff, made a dashing little attack on his own, and drove the enemy back, receiving a wound in the exploit. The Twenty-first Division, save on the right, had all its objectives. The left of the Third Corps had not prospered equally well, so that a defensive line had to be built up by Campbell in the south, while Robertson did the same in the north, the whole new position forming a marked salient. Two efforts of the enemy to regain the ground were beaten back. The southern divisions had been much troubled by flanking fire from Gouzeaucourt, so an effort was made that night to get possession of this place, the 6th Dorsets and 10th West Yorkshires of the 50th Brigade suffering in the attempt. This attack was led by General Sanders, who had succeeded Gwyn, Thomas as Brigadier of the 50th, but he was himself killed by a shell on September 20. Some 2000 prisoners and 15 field-guns were the trophies taken in this operation by the Fifth Corps. Gouzeaucourt was shortly afterwards evacuated, but there was no other change on the front until the great battle which shattered the Hindenburg Line and really decided the war. All of this fighting, and especially that on September 18, has to be read in conjunction with that already narrated in the story of the Fourth Army on the right.

Having brought Shute’s Fifth Corps up to the eve of the big engagement we shall now ask the reader to cast his mind back to August 21, the first day of General Byng’s advance, and to follow Haldane’s Sixth Corps on the northern flank of the Army during these same momentous and strenuous weeks. It will then be more easy to trace the operations of Harper’s Fourth Corps, which was intermediate between Shute and Haldane.

Haldane’s Sixth Corps, like its comrades of the Third Army, had gone through the arduous days of March and had many a score to pay back to the Germans. It was a purely British Corps, consisting upon the first day of battle of five fine divisions, the Second (Pereira), Third (Deverell), Sixty-second (Braithwaite), Fifty-ninth (Whigham), and the Guards. With four Regular units out of five, Haldane’s Sixth Corps might have been the wraith of the grand old Mons army come back to judgment. The First Cavalry Division, also reminiscent of Mons, was in close support, ready to take advantage of any opening.

The first advance in the early morning was made by the 99th Brigade of the Second Division on the south, and the 2nd Guards Brigade on the north, the latter being directed upon the village of Moyenneville, while the 99th Brigade was to carry Moyblain Trench, the main German outpost position, 1000 yards in front of the line. The right of the line was formed by the 1st Berks and the left by the 23rd Royal Fusiliers, the latter having a most unpleasant start, as they were gas-shelled in their assembly places and had to wear their masks for several hours before zero time. Any one who has worn one of these contrivances for five consecutive minutes will have some idea what is meant by such an ordeal, and how far it prepares a man for going into battle. Only a very expert man can keep the goggles clean, and one is simultaneously gagged, blinded, and half smothered, with a horrible death awaiting any attempt at amelioration.

At five o’clock nine tanks moved forward behind a crashing stationary barrage, and the infantry followed eagerly through a weak German fire. In spite of all precautions the Fusiliers had lost 400 men from gas, but otherwise the casualties were very small. It may be remarked that many of these serious gas cases occurred from the reek of the gas out of the long grass when the sun dried the dew, showing how subtle and dangerous a weapon is this distillation of mustard. Some small consolation could be gained by the British soldier suffering from these hellish devices, by the knowledge that our chemists, driven to retaliate, had in mustard gas, as in every other poison, produced a stronger brew than the original inventor. Well might the German garrison of Lens declare that they wished they could have dropped that original inventor into one of his own retorts.

The advance of the Guards kept pace on the left with that of the Second Division. The 2nd Brigade went forward with Moyenneville for its immediate objective. The 1st Coldstream in the north were to carry the village, while the 1st Scots were to assemble in the low ground north of Ayette, and to carry the attack to the Ablainzeville-Moyenneville Ridge. The 3rd Grenadiers were then to pass through the Scots and to capture the line of the railway. The opening of the attack was much the same as in the case of the troops on the right, save that no difficulty was experienced from gas. There were few losses in the two leading battalions, which took many prisoners, and it was only the 3rd Grenadiers who, as they neared the railway, met a good deal of machine-gun fire, but pushed on in spite of it and made good the line of their objective.

In the meantime the 9th Brigade of the Third Division had moved through the ranks of the 99th Brigade, and had carried on the advance in the southern area. They advanced with the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers on the right and 4th Royal Fusiliers behind them. The latter had the misfortune to lose Colonel Hartley and 50 men from a shell-burst while moving into position. The left front of the brigade was formed by the 13th King’s Liverpools. The whole line advancing in open order passed on without a check, save from mist which caused loss of direction and constant reference to the compass. Over a series of trenches the line plodded its way, clearing up occasional machine-guns and their crews. By 9.15 they were on the railway embankment.

The 8th Brigade (Fisher) of the Third Division had also advanced on the left of the 9th, keeping pace with it so far as the fog would allow. The 7th Shropshires were on the left, in touch with the Guards. The 1st Scots Fusiliers were on the right and the 2nd Royal Scots in support. The attack was directed upon Courcelles, which was carried by the Scots Fusiliers and mopped up by the 8th Royal Lancasters. From the village a sharp slope leads down to the railway line and here the opposition was very strong, the ground being closely swept by rifle and machine-gun fire. Behind two tanks the leading battalions rushed forward and the railway was rushed, with 200 prisoners. The position was organised, and touch established with the Guards on the left and with the 9th Brigade on the right. The 9th Brigade found it difficult, however, to get touch with the Sixty-third Naval Division on their right, that unit having experienced considerable difficulties and losses. The 76th Brigade, the remaining unit of the Third Division, had the 2nd Suffolks and 1st Gordons close up to the line, and all of these battalions were much mixed up owing to the persistent fog.

A very determined pocket of German infantry and machine-gunners had remained in front of the left flank of the Sixty-third Division, formed by the 188th Brigade. These men were now on the right rear of the 9th Brigade, but the situation was obscure and nothing was certain save that the British line was not yet continuous and solid. In spite of a concentration of artillery the Germans were still holding out next morning, being the only hostile units to the west of the railway line on the Sixth Corps sector.

An attempt had been made to get forward to Achiet-le-Grand, in which part of the Sixty-third Division on the right and two companies of the Gordons participated. The Ansons and the Gordons both lost considerably in this attack and were unable to reach the village, though they advanced the line by 500 yards. Lack of artillery support, while the enemy guns were numerous and active, was the cause of the check.

The night of August 21 was quiet on most parts of this new front of the Third Army, but at early dawn a counter-attack developed before the Sixty-third Division and before the 8th Brigade. An S.O.S. barrage was called for and promptly given in each case, which entirely extinguished the attack upon the Sixty-third. On the 8th Brigade front some of the German infantry got as far forward as the railway line but were quickly hurled back again by bombs and the bayonet. At 7.45 A.M. the enemy again made a rush and occupied one post of the railway, from which, as well as from the posts on the right of the 9th Brigade where the railway line was not yet in British hands, he enfiladed the front defences during the day, causing many casualties, until in the evening the post was retaken by the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers. Among the gas cases sent to the rear this day, though his injuries had been incurred during the assembly, was General Fisher of the 8th Brigade.

The Guards in the north had also encountered the attack of the early morning of August 22, which seems to have been general along the line, though at no part very vigorous. This particular section of it was delivered near Hamelincourt by the Fortieth Saxon Division, who suffered terribly in the venture. The rest of the day was comparatively quiet and was spent in arranging the attack for the morrow. This attack was planned with the idea of outflanking the German position at Achiet-le-Grand, which had shown itself to be dangerously strong. It was determined to outflank it both upon the north and the south. With this intention the Third Division was to capture Gomiecourt during the night of August 22. Farther north two fresh divisions, the famous Fifty-sixth London Territorials, and the Fifty-second from Palestine, were ordered to prolong the line of the Guards, all under General Haldane, and to capture Hamelincourt, Boyelles, and Boiry Becquerelle, with as much more as they could get, on the early morning of August 23. On the front of the Fourth Corps on the right the advance was entrusted to the Thirty-seventh Division and to the Forty-second Division on the bank of the Ancre.

The attack upon Gomiecourt, which was to be the prelude of the day’s work, since all advance to the south was impossible while that village was in German hands, was carried out by the well-tried 76th Brigade, the 8th Royal Lancasters and 2nd Suffolks in the front line, with the 1st Gordons in close support. Tanks were to lead the van, but they were unable to get across the railway embankment in time. The assault, which began at 4 in the morning, was preceded by a short crashing bombardment of heavy shells upon the doomed village. It had hardly ceased before the Suffolks and Lancasters were swarming down the street, and the place was secured with little loss. Whilst this brisk and successful affair was going on, the 13th King’s Liverpools of the 9th Brigade on the right made an advance to keep the line level, taking some prisoners and three guns. This was the more important as the weak point of the situation had always been to the south and most of the damage sustained was by enfilade fire from this direction.

The 8th Brigade, now under the command of Colonel Henderson, kept pace with the 76th Brigade in their advance, occupying the ground north of Gomiecourt. The 2nd Royal Scots and 7th Shropshires were in the lead. There was very heavy fire and the losses were considerable, but the machine-gun nests were rooted out with the bayonet, and the full objective was attained. Farther north the attack was carried on by the 3rd Grenadier Guards and the 1st Scots. These were successful in taking the village of Hamelincourt and the trench system south of it, while keeping in touch with the Fifty-sixth Division to the north of them. The 1st Coldstream was then pushed through and crossed the Arras—Bapaume Road, gaining a position eventually from which they looked south upon Ervillers.

Farther north still both the Fifty-sixth and the Fifty-second Divisions had joined in the advance, moving forward to the line of the great high road which runs from north to south. Bridges had been thrown over the Cojeul River by the sappers of the Fifty-ninth Division, who had held this front—the workers having to wear gas masks during their labours. To the 470th Field Company R.E. belongs the credit of this most difficult job, under the direction of Colonel Coussmaker. Over these bridges passed the Fifty-second Division, while south of them the attack was urged by the 168th Brigade of the Fifty-sixth Division, with several villages for their objective. The 13th London (Kensingtons) were on the right, the 4th London in the centre, and the 14th London (London Scottish) on the left. The advance went without a hitch, save that touch was lost with the Guards on the right. This was regained again in the evening, however, when the Brigade found itself to the north of Croisilles and close to the old Hindenburg Line. The Fifty-second Division had also reached the line where it runs across the Sensée valley.

The main advance in front of Haldane’s Corps had been entrusted to the Second Division, who advanced through the ranks of the Third Division after the capture of Gomiecourt. This advance was on a three-brigade front. On the right was the 99th Brigade, in touch with the 63rd Brigade of the Thirty-seventh Division to the south of them. This Brigade was told off to keep the flank, but it captured 500 prisoners in the process. On the left was the 6th Brigade, which had been ordered, with the help of eight whippets, to attack Ervillers. In the centre the 5th Brigade with ten whippets was to carry Behagnies and Sapignies. This considerable attack was timed for 11 o’clock.

Gomiecourt having fallen, the 5th Brigade used it as a screen, passing round to the north of it and then turning south to Behagnies. The 2nd Highland Light Infantry headed for that village, while the 24th Royal Fusiliers advanced to the storm of Sapignies. The 2nd Oxford and Bucks were in reserve. The ten light tanks which led tie attack had a series of adventures. Three were knocked out by a gun on the railway. The other seven under heavy gun-fire swerved to the right, got out of the divisional area, and on the principle that any fight is better than no fight, joined with the Thirty-seventh Division in their attack upon Achiet-le-Grand, where they did good service. In the meantime, the tankless 5th Brigade moved round Gomiecourt, coming under very heavy fire on their left flank. Colonel Brodie, a most gallant V.C. officer of the Highland Light Infantry, was killed, and Colonel Cross of the Oxfords wounded, by this fire. The day was very hot, the men exhausted, and the losses severe. The new position was organised, therefore, and the advance suspended for the present.

The 6th Brigade had advanced on the left of the 5th, heading for Ervillers, with the let King’s Liverpools and the 2nd South Staffords in the lead. The front waves, assisted by light tanks, rapidly broke down all opposition, and Ervillers was taken about 2 P.M. All movement beyond the village was checked by very heavy fire from the high ground to the north-east, so that Mory Copse, the next objective, was found to be unattainable. The object of the British Commanders was never to pay more for a position than it was worth, or buy a machine-gun at the cost of half a battalion. On the other hand, papers captured during the day showed beyond all doubt that the object of the Germans was to make an orderly retreat as far as the Hindenburg Line, so that it was clearly the game to hustle and bustle them without cessation.

August the 24th was a heavy day in the Sixth Corps, who were ordered to push on and gain ground to the utmost extent along the whole front. In order to strengthen the movement, the Canadian Corps had been very quietly and deftly removed from the right wing of Rawlinson’s Army and transferred to the left wing of Byng’s Army, in touch with the Fifty-second Division.

It will be remembered that the Second Division, though they had taken Ervillers, had been pinned down there by German fire, while they had failed to take Behagnies or Sapignies. Both these movements were now resumed. In the night of August 23-24 the 1st King’s Liverpools advanced from Ervillers upon Mory, but were held up by very heavy fire. The 3rd Guards Brigade on the north was advancing successfully upon St. Leger and this had the effect of outflanking the Mory position on that side. St. Leger was taken by the 2nd Scots Guards and the 1st Welsh, who cleared it in the course of the afternoon. They could get no farther, however, until the Second Division had completed its task at Mory. This was now in the hands of the 99th Brigade, who, headed by the 1st Berkshires, with the 1st Royal Rifles behind them, and a spearhead of tanks in front, broke down all opposition and captured Mory Copse, a very formidable position full of emplacements and dug-outs. By this success the threat was removed from the right of the Guards, and all was clear for their further advance upon Ecoust.

The Sixty-second Yorkshire Division had now moved up to relieve the Second Division, but the latter were determined before their withdrawal to complete their unfinished tasks. In the early morning of August 25 the attacks upon the two obdurate villages were resumed, after a very heavy bombardment. The new venture was splendidly successful. The 2nd Highland Light Infantry and the 24th Royal Fusiliers rushed into Behagnies while it was still dark and cleared out the whole village. This enabled the force to get to the rear of Sapignies, which was stormed by the 2nd Oxfords—a battalion with such proud traditions that even now in semi-official documents it is still the 52nd Light Infantry. 300 prisoners and 150 machine-guns were taken in the village, a proportion which illustrates how far machines were taking the places of men in the depleted German Army. Haring gloriously tidied up its front the Second Division now stood out while the Sixty-second took its place.

It will be remembered that the Fifty-second and Fifty-sixth Divisions had fought their way to the Hindenburg Line on August 23. This was too formidable an obstacle to be taken in their stride, and the most that could be hoped was that they should get into a good position for the eventual attack. The Fifty-second Division had shown the metal of the Palestine Army by a very fine advance which made them masters of Henin. On their right was the 167th Brigade, with the 1st London and the 7th and 8th Middlesex in the line. These troops pushed right into the outskirts of Croisilles, but it was clear that new German divisions were in the line, and that the resistance had very much hardened. The Londoners were unable to hold the village, and the Fifty-second Division was also held up on Henin Hill by very strong fire. Matters seemed to have come to a stand in that quarter.

Early on the morning of the 25th the Guards 3rd Brigade and the 186th and the 187th Brigades of the Sixty-second Division made a resolute advance to clear their front and get nearer to that terrible paling which was meant to enclose the German domain. It was a day of very hard fighting for all three brigades, and they had ample evidence that the German line had indeed been powerfully reinforced, and had no intention of allowing General Byng to establish himself in the very shadow of their fortifications if they could hold him off. The opening was inauspicious, for by some mistake there was an error of half an hour in starting-time between the two divisions. As a result the Guards found themselves on the line of road between Mory and St. Leger with an open flank and under heavy enfilade fire, which made many gaps in the ranks of the 1st Grenadiers. At the same time the leading tanks were put out of action on that flank. In the centre the tanks lost their way in the mist, but the 2nd Scots Guards pushed ahead in spite of it. Banks Trench, however, in front of them was very strongly held and the assault was not pressed. On the left the 1st Welsh were in St. Leger Wood, but Croisilles was still untaken and the advance could not be carried forward as the machine-guns from this village swept the country. About 9 A.M. the enemy buzzed out of the Hindenburg Line and fell upon the Scots Guards, but were shot back again into their cover. During these operations the Guards captured a battery of field-guns.

The Sixty-second West Yorkshire Territorials on the right of the Guards had an equally arduous day. They had found the same difficulties in getting forward, but at 5 P.M. the enemy had the indiscretion to counter-attack, and when once he masks his own machine-guns he has ceased to be formidable. His attack was near Mory Copse and aimed at the junction between the two divisions, but it was heavily punished and shredded away to nothing. About 7 P.M. he tried another advance upon the right of the Sixty-second Division and won his way up to the line, but was thrown out again by the 5th West Ridings and driven eastward once more. The 186th Brigade, forming the right of the division, co-operated with the Fourth Corps in their attack upon Favreuil, which place was captured.

On the evening of August 25 Haldane’s Sixth Corps, which had become somewhat unwieldy in size, was limited to the north on a line just south of Croisilles, so that the Fifty-second, Fifty-sixth, and Fifty-seventh Divisions all became Fergusson’s Seventeenth Corps, which was thus thrust between the Sixth Corps and the Canadians, who had not yet made their presence felt upon this new battle-ground. The Seventeenth Corps was now the left of the Third Army, and the Canadians were the right of the First Army. The immediate task of both the Sixth and Seventeenth Corps was the hemming in and capture of Croisilles, and the reoccupation of the old army front line. August 26 was a quiet day on this front, but on August 27 the Guards and the Sixty-second Division were ordered forward once more, the former to attack Ecoust and Longatte, the other to storm Vaulx-Vraucourt. The First German Division encountered was easily driven in. The second, however, the Thirty-sixth, was made in a sterner mould and was supported by a strong artillery, large and small. The 2nd Grenadiers and 2nd Coldstream in the front line of the Guards 1st Brigade got forward for nearly a mile on each flank, but were held up by a withering fire in the centre, so that the flanks had eventually to come back. The Fifty-sixth Division of the Seventeenth Corps had not yet captured Croisilles, from which a counter-attack was made upon the left flank of the 2nd Coldstream, which was handsomely repulsed.

On the whole, however, it had been an unsatisfactory day and the Sixty-second had been equally unable to get forward, so that none of the objectives had been gained. The Seventeenth Corps and the Canadians in the north were both advancing, however, and it was possible that the position in the south might alter as a consequence.

Such was indeed found to be the case on August 28, for the Fifty-sixth Division was able this day to get possession of Croisilles, which eased the situation to the south. The Guards and the Sixty-second pushed forwards, following always the line of least resistance, so that by evening they were 1200 yards forward at some points, though the right of the Sixty-second Division was still pinned to its ground. That evening the Third Division replaced the Guards, and the same tactics were pursued on the following day. The 76th Brigade was now in the front line to the south of Croisilles, with the hard-worked Sixty-second Division still on their right. A sugar factory was the chief impediment in front of the latter. The right of the division got forward during the day and occupied the old army trenches.

August 30 was once again a day of heavy fighting, the Seventeenth and Sixth Corps, represented by the Fifty-sixth, Third, and Sixty-second Divisions, closing in upon the Hindenburg Line and attacking the last villages which covered its front. The tanks had miscarried, and the infantry at 5 A.M. had to go forward alone. On the right the 185th and 186th Brigades of the Sixty-second Division both made good progress, the obnoxious sugar factory was taken, and though Vaulx could not be cleared it was partly occupied. Next day saw the dour Yorkshiremen still sticking to their point, and fighting with varying success in and out of the village. At times they had flooded through it, and yet again they were beaten back. By the morning of September 1 the 186th Brigade had possession of Vaulx-Vraucourt and were on the high ground to the east of the village. Next morning they had Vaux Trench as well, but about ten o’clock in the forenoon of September 2 a strong counter sent them reeling back in some disorder. Gathering themselves together in grim North Country fashion they went forward again and cleared Vaulx Wood before evening. That night, after a very desperate and costly term of service, the Sixty-second was relieved by the Second Division.

The experiences of the Third Division from the August 30 attack were as arduous as those already described. On that morning the 76th Brigade, with the Suffolks and Gordons in the lead, got forward well at the first, though they lost touch with the Londoners to the north. The Suffolks were on that side and the gap enabled the Germans to get round to their left rear with disastrous results, as the losses were heavy and the battalion had to fall back. The Gordons had to adjust their line accordingly. This rebuff had lost most of the ground which had been gained early in the day, General Deverell now sent up the 9th Brigade, as the 76th was much worn, but the 1st Gordons remained in the fight.

On August 31 the 9th Brigade attacked the Vraucourt position, with the 1st Gordons, battle-weary but still indomitable, on the right, the 4th Royal Fusiliers in the centre, and the 13th King’s Liverpools on the left. It was known that no less than three new German divisions had been thrown in, and however the fighting might turn it was certain that the attrition was going merrily forward. The assembly was unfortunately much disturbed by the German barrage, which fell with particular severity upon the Fusiliers in the centre. At 5.15 A.M. the line moved forward, but again the luck was against the Fusiliers, who were opposed by a particularly dangerous machine-gun nest in a sunken road. One company endeavoured to rush it, but all the officers save one, and most of the men, were mown down. A tank which endeavoured to help them met with a strange fate, as a German officer managed, very gallantly, to get upon the top of it, and firing through the ventilation hole with his revolver, put the whole crew out of action—a feat for which in the British service he would certainly have had his V.C.

The Fusiliers were hung up, but the King’s on the left had carried the village of Ecoust, getting in touch with the right of the Fifty-sixth Division in Bullecourt Avenue. Many hundreds of the enemy were taken, but some pockets still remained on the southern edge of the village, and fired into the flank of the unfortunate Fusiliers. The King’s then attempted during the long day to throw out their right flank and get in touch with the left of the Gordons so as to obliterate the sunken road, which was the centre of the mischief. The ground was absolutely open, however, and the fire commanded it completely. Under these circumstances Colonel Herbert of the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, which was in reserve, suggested that the attack be postponed until dusk. This was done, and at 8 P.M. Herbert’s men overran the sunken road, capturing the guns. Ecoust was also completely cleared of the enemy. So ended this day of vicissitudes in which the 9th Brigade, with heavy loss, had struggled through many difficulties and won their victory at the last. A further advance during the night by both the 9th and the 76th Brigades straightened the whole line from Ecoust to the south.

On the morning of September 1 the Fifty-second Division had relieved the Fifty-sixth Division, both of the Seventeenth Corps, in the Croisilles sector, and was in close touch with the Third Division to the south. Both divisions went forward with no great difficulty at the appointed hour, the three battalions of the 9th Brigade being all in the line once more. The important trench known as Noreuil Switch was captured in this advance. It may well seem to the reader that the gains were tardily and heavily bought at this stage of the operations, but it is to be always borne in mind that Fergusson and Haldane in particular were up against the old intricate trench system, and away from that open fighting which can alone give large results. To others there was always some way round, but here there was an unbroken obstacle which must be frontally attacked and broken down by pure persistence. In these operations the new machine-gun organisation proved to be particularly efficient, and B Company of the 3rd Battalion Machine-Gun Corps did essential work in winning the way for the 9th Brigade. The whole battle was a long steady contest of endurance, in which the Germans were eventually worn out by the persistence of their opponents.

The advance was renewed along this area on September 2, the object of the Fifty-second Division being to encircle Quéant from the south and west, while that of the Third and Sixty-second Divisions was to gain the east of Lagnicourt and the high ground east of Morchies. The fortunes of the Sixty-second Division have already been briefly described. On the front of the Third Division the 8th Brigade, strengthened by one battalion from each of the other brigades, took up the heavy task, the 7th Shropshires, 2nd Royal Scots, and 1st Scots Fusiliers forming from right to left the actual line of battle. The last-named battalion by a happy chance joined up on the left with its own 5th Battalion in the Fifty-second Division. They assembled under heavy shelling, some of which necessitated the use of box-respirators. No sooner had the advance begun than the Shropshire men came under machine-gun fire and lost the three tanks which led them. They had gained some ground, but were first brought to a halt and then compelled to retire. In the centre the Royal Scots took Noreuil, which was found to be lightly held. In attempting to get on to the east of this village they found the trenches strongly manned and the fire, both of rifles and machine-guns, so murderous that it was impossible to get forward. The Scots Fusiliers were also faced with strong resistance, including a belt of wire. Three company and eight platoon commanders were down before this obstacle and the sunken road behind it were crossed. Without the aid of tanks the depleted battalion moved on under very heavy fire, and eventually halted in a line with the Royal Scots on their right. To the right of these, as already shown, the Sixty-second Division had also been brought to a stand. A formidable trench, called in the old British days Macaulay Avenue, barred the way and had only been reached by a few of the assailants. It is a fact, however, that Lieutenant R. R. MacGregor of the Scots Fusiliers with five men did force their way in upon this morning, and tenaciously held on to their position until after dark, forming just that little nucleus of determined men by whom great battles are so often won.

There was a momentary check, but it was retrieved by Captain Nagle’s company of the 2nd Suffolks, who charged with two companies of the Royal Scots and won a section of the trench. The utmost difficulty was experienced by the Brigadier in keeping in touch with the action, as the ground was so exposed that nearly every runner sent back from the front line was killed or wounded. Colonel Henderson came forward, therefore, about three o’clock and reorganised his dispositions, with the result that before evening the line had been straightened and advanced, with the capture of many prisoners and machine-guns. Meanwhile Quéant to the north had been captured by the Fifty-second Division, and the whole German system of defence was weakening and crumbling, the Seventeenth Corps strongly co-operating with the Canadians upon their left. The enemy’s purpose during all this very hard contest was to sacrifice his rearguards if necessary, in order to cover the retreat of his main body across the Canal du Nord. There were few more difficult problems in local fighting during the whole war than how to carry these successive positions, bravely held and bristling with machine-guns. That it was finally done was a great achievement upon the part both of those who commanded and those who obeyed. Colonel Vickery’s guns, covering the infantry, had much to do with the final success. How great that success was could only be judged upon the following morning when the new divisions which had taken over the front, the Guards on the left and the Second on the right, found that all the kick had been taken out of the Germans, and that a substantial advance could be made with little loss.

Neither the Guards nor the Third Division encountered serious opposition upon September 3, and a steady, if cautious, forward movement went on all day. The Seventeenth Corps upon the left had turned south in order to clear Moouvres and Tadpole Copse. By midday the Second Division had cleared both Hermies and Demicourt. Before evening the 2nd Guards Brigade was in the old British front line, which was held during the night. The Canal du Nord was just ahead, and it was realised that this would mark what the Germans intended to make their permanent line. It was all-important to push the rearguard across it and to get any bridges with their eastern exits, if it were in any way possible.

The advance on September 4 was resumed in the face of some sporadic opposition, but by the evening of the 6th the enemy was all across the Canal, and the Sixth Corps was awaiting developments elsewhere. On September 11 steps were taken, however, to get into striking position for the final fracture of the Hindenburg Line, in view of which it was necessary to gain the Hindenburg front system west of the Canal. On September 12 the main attack was delivered, though on September 11 the Second Division had secured the western ends of the Canal crossings. The centre of the new operation was the attack upon Havrincourt by Braithwaite’s Sixty-second Division. This operation was carried out by the 186th and 187th Brigades, the pioneer battalion, 9th Durham Light Infantry, being attached to the former, while eight brigades of field-guns and three groups of heavies lent their formidable assistance. The right of the Sixty-second was in close touch with the Thirty-seventh Division, which was attacking Trescault. The advance of both brigades was uninterrupted, though strongly opposed. The 2/4th Hants and 5th West Ridings on the right, and the 2/4th York and Lancasters with the 5th Yorkshire Light Infantry on the left, trampled down all opposition. The individual is almost lost to sight in the scale of such operations, but a sentence must be devoted to Sergeant Calvert of the last-named battalion, who attacked two machine-guns, bayoneted four and shot three of the crews, taking the rest prisoners. At 7.30, the western edge of the village of Havrincourt had fallen, but the fortified château on the south, in the area of the 186th Brigade, still held its own. It was attacked by the 2/4th West Riding Battalion, who had a most difficult task in the tangled gardens which surrounded the house. At the same time the 2/4th Hants pushed into the village and fought their way right through it. They had to sustain a heavy counter-attack delivered about 7 in the evening by the Twentieth Hanoverian Division, supported by a flight of low-flying aeroplanes. This attack was broken up with great loss by the steady fire of the men of Hampshire and Yorkshire.

In the early morning of September 13 the village was strongly attacked by the enemy, who effected a lodgment in the cemetery and pushed back the British line for 200 yards. A fine return was made by the 5th Devons of the 185th Brigade, who cleared the village once again. Two of the divisional machine-guns held out close to the posts occupied by the Germans—so close that the sergeant in charge shot the battalion leader of the enemy with his revolver. From this time the Sixty-second were left in possession of Havrincourt, which they had thus won for the second time, since it was carried by them in the Cambrai battle of November 20, 1917. General Braithwaite, who was the victor upon each occasion, remarked that if his men had to take it a third time they should, on the cup-tie principle, be allowed to keep it for ever.

Meanwhile the Second Division on the left had made its way slowly but without any serious check as far as London Trench, which brought them nearly level with the Sixty-second, while the Thirty-seventh in the south had captured Trescault and were also well up to the Hindenburg Line. There was no further serious fighting for several days on this front save that the 185th Brigade advanced its line to Triangle Wood on the morning of September 14. This attack was carried out by the 2/20th Londons and was completely successful, as was their subsequent defence against a brisk counter-attack. On September 16 the Sixty-second Division was relieved by the Third, and the Second Division by the Guards. There was no further fighting until September 18, that general day of battle, when a very severe German attack was made about 6 o’clock in the evening, which covered the whole front of the Third Division and involved the left of the Thirty-seventh Division in the area of the Fourth Corps. After a heavy bombardment there was a determined advance of infantry, having the recapture of Havrincourt for its objective. A number of low-flying aeroplanes helped the German infantry. The attack fell chiefly upon the 1st Scots Fusiliers and 2nd Royal Scots, and some gain was effected by a rush of bombers aided by flame-throwers, but they were finally held and eventually driven back, while 100 prisoners were retained. C Company of the Royal Scots particularly distinguished itself in this action, forming a solid nucleus of resistance round which the whole defence was organised. Nothing further of importance occurred until September 27, the day of the general advance, in this northern portion of the British line.

In order to complete this account of the doings of Byng’s Third Army from August 21 onwards, some account must now be given of what was originally the central unit, Harper’s Fourth Corps, though its general progress has already been roughly defined by the detailed desoription of the two Corps on its flanks.

The first task set for this Corps on August 21 was to capture the general line between Irles in the south and Bihucourt in the north, while the flank of this main attack was to be guarded by a subsidiary advance along the valley of the Ancre, and between Puisieux and Miraumont. The first objective of the main attack was Bucquoy, Ablainzeville, and the important high ground to the immediate east of these villages.

The advance commenced in a thick mist, and was undertaken in the case of the main attack by Williams’ Thirty-seventh English Division. It was completely successful, and aided by the fire of six heavy and fifteen field brigades of artillery, it swept over its first objectives, the tanks helping materially to break down the opposition. The moral effect of a tank in a fog can be pictured by the least imaginative. Two field-guns and many lighter pieces were taken. The veteran Fifth Division on the right and the Sixty-third Naval Division on the left then passed through the ranks of the Thirty-seventh to enlarge the opening that they had made, carrying the advance on to the limit of the field artillery barrage, and halting at last just west of Achiet-le-Petit. The naval men met with a blaze of machine-gun fire from the edge of Logeast Wood, but they rooted out the nests and occupied the position, though the passage through the tangled brushwood and trees disorganised the units, and progress became slow. The railway line ran right across the front, and this, as usual, had become a formidable and continuous obstacle, which could not be turned. The reserve brigade of the Fifth Division on the right carried Achiet-le-Petit, but could not get over the railway. The Sixty-third was also unable to reach the railway, and found a considerable concentration of Germans opposite to them in the brickworks and cemetery west of Achiet-le-Grand. The tanks had wandered off in the mist, and for the moment the advance had reached its limit. Many of the tanks, as the mist lifted, were hit by the anti-tank guns of the enemy, though some most gallantly crossed the railway line and penetrated the German positions, doing such harm as they could, until they were eventually destroyed.

Meanwhile, the subsidiary attack on the right flank had also been successful up to a point. The New Zealanders on the immediate south of the Fifth Division had gone forward in their usual workmanlike fashion, and had taken Puisieux. Upon their right, and next to the Fifth Corps who were beginning their arduous crossing of the Ancre, was the Forty-second Division (Solly-Flood), an ex-Palestine unit of Lancashire Territorials which had won laurels in the March fighting. It had come away with a flying start, and had got as far as the important point named Beauregard Dovecote. There it remained until the early morning of August 22, when the enemy regained it by a spirited attack from a new division. The total effect of the day’s work along the whole front of the Fourth Corps had been the capture of 1400 prisoners, of a number of guns, and of an extent of ground which was important, though less than had been hoped for. The main resistance had always been the railway, and the German guns behind it, so that to that extent his line was really inviolate. Indeed from his point of view the whole work of the Third Army on that date might be represented as an attack upon a false front, the real position remaining intact.

The enemy was by no means abashed, and early in the morning of August 22 he showed that he did not propose to surrender the field until he had fought to regain it. At dawn the Fifty-second German Division deployed through Miraumont and fell upon the left of the Fifth Division in one direction, and the Forty-second in the other. As already stated they succeeded in driving back the latter, and Beauregard Dovecote remained as a prize of victory. Some three hundred Germans pushed through between the Fifth Division and the New Zealanders, but were at once attacked by a party of the 1st Devons, assisted by some of the New Zealanders. Corporal Onions of the Devons showed great initiative in this affair, which ended in the capture of the whole of the intruders. He received the V.C. for his gallantry.

It was a day of reaction, for the Sixty-third Division in the north was strongly attacked, and was at one time pushed as far as Logeast Wood. They rallied however and came back, but failed to regain the railway at Achiet-le-Grand. Early in the morning of August 23 the Beauregard Dovecote was finally captured by units of the Forty-second and New Zealanders, the enemy falling back to Miraumont. About the same hour in the morning the Sixth Corps in the north had taken Gomiecourt as already described, which strengthened the general position.

Early on August 23 the Thirty-seventh Division came up on the left and relieved the Naval Division. Guns had been pushed into position, so at it o’clock in the forenoon it was possible to deliver a strong attack under an adequate barrage upon the line of the railway. The result was a complete success, in spite of the formidable nature of the defences. The imperturbable English infantry flooded over every obstacle, took its inevitable losses with its usual good humour, and established itself upon the farther side of the position, while the tanks, taking advantage of a level crossing, burst through and did very great work. Both Achiet-le-Grand and Bihucourt fell to the Thirty-seventh Division, while the Fifth captured the high ground overlooking Irles, and subsequently pushed on eastwards as far as Loupart Wood. Since Miraumont was still German the flank of Ponsonby’s Division was scourged by the machine-guns, and an attempt by the Forty-second Division to relieve the pressure by taking the village had no success, but the Fifth maintained all its gains in spite of the heavy enfilading fire. In this fine operation the Thirty-seventh Division alone captured 1150 prisoners. There were signs, however, of German reaction, especially on the southern flank, where a new division, the Third Naval, had been brought into line.

August 24 was another day of victory. The New Zealanders passed through the depleted ranks of the Fifth Division and made good not only the whole of Loupart Wood, but also Grevillers to the north-east of it. An even more useful bit of work was the storming of Miraumont by the Forty-second Division in the south. This village, which had been nearly surrounded by the advance on the flanks, gave up 500 prisoners and several guns. The Forty-second continued its career of victory to Pys, which they took, and were only stopped eventually by the machine-guns at Warlencourt. This advance greatly relieved the situation on the right flank, which had been a cause for anxiety, and it also, by winning a way to the Ancre, solved the water problem, which had been a difficult one. This day of continued victorious advance was concluded by the occupation of Biefvillers by the united action of the Thirty-seventh and of the New Zealanders.

At 5 A.M. upon August 25 the advance was resumed, with the Sixty-third Division on the right, the New Zealanders in the centre, and the Thirty-seventh on the left. The naval men found a head wind from the first, for the Germans were holding Le Barque and Thilloy in great strength. No great progress could be made. On the left the New Zealanders and the Thirty-seventh both reached the very definite line of the Bapaume—Arras Road, where they were held by very heavy fire from Bapaume on the right and Favreuil on the left. The splendid Thirty-seventh, with some assistance from the New Zealanders on their south, rushed the wood and village of Favreuil and helped to beat off a German counter-attack by the fresh Hundred and eleventh Division, which was so mauled by aircraft and artillery that it never looked like reaching its objective. Many dead and some abandoned guns marked the line of its retirement.

On August 26 these indefatigable troops were still attacking. It was indeed a most marvellous display of tenacity and will-power. The general idea was to encircle Bapaume from the north and to reach the Cambrai Road. In this the Fifth Division and the New Zealanders were successful, the former reaching Beugnatre, while the latter got as far as the road, but sustained such losses from machine-gun fire that they could not remain there. In the south Thilloy still barred the advance of the Naval Division, which was again repulsed on August 27, when they attacked after a heavy bombardment. There was a pause at this period as the troops were weary and the supplies had been outdistanced. On August 28 the Sixty-third left the Fourth Corps and the Forty-Second took over their line and repeated their experience, having a setback before Thilloy. On August 29 there was a general withdrawal of the German rear-guards, the whole opposition dissolved, Thilloy fell to the Forty-second Division, and the New Zealanders had the honour of capturing Bapaume. Up to this time the advance of the Fourth Corps had yielded 100 guns and 6800 prisoners.

On August 30 the whistles were sounding once more and the whole British line was rolling eastwards. It will mark its broader front if we say that on this date the Fifth Corps on the right was in front of Beaulencourt, while the Sixth Corps on the left had taken Vaulx, Vraucourt. The Forty-second Division on this day was unable to hold Riencourt, but the rest of the line got well forward, always fighting but always prevailing, until in the evening they were east of Bancourt and Frémicourt, and close to Beugny. Always it was the same programme, the exploring fire, the loose infantry advance, the rapping machine-guns, the quick concentration and rush—occasionally the summoning of tanks or trench mortars when the strong point was obstinate. So the wave passed slowly but surely on.

On August 31 the Germans, assisted by three tanks, made a strong attack upon the New Zealanders, and a small force pushed in between them and the Fifth Division. They were surrounded, however, a German battalion commander was shot and some sixty of his men were taken. The whole line was restored. On this day the Lancashire men on the right took Riencourt with some prisoners and a battery of guns.

September 2 was a day of hard battle and of victory, the three Corps of General Byng’s Army attempting to gain the general line Barastre—Haplincourt—Le Bucquière. The Forty-second Division captured Villers-au-Flos and advanced east of it, while the New Zealanders made good the ridge between there and Beugny. Some 600 prisoners were taken. There was some very fierce fighting round Beugny in which the Fifth Division lost six tanks and many men with no particular success. The place was afterwards abandoned.