There is no professional consensus on an appraiser’s responsibilities in fraud prevention. It is a matter that has not even been introduced for discussion yet. Some prominent appraisers believe that fraud prevention is outside the scope of work expected from appraisers and that lenders “get what they deserve” when dealing with dishonest borrowers. The recent global financial crisis has indeed punished careless lenders, but with far-reaching consequences to millions of innocent people. The public deserves better than this. Other prominent appraisers believe that compliance with the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice (USPAP) is all that is needed to accomplish fraud prevention. Recent court decisions may cause them to rethink this position.

The appraisal profession in the United States originally emerged to correct the financial abuses leading to the bank failures and Great Depression of the 1930s. From its origins it has been implicitly understood that the appraisal profession exists to protect the public, much like the public accounting profession. More recently, USPAP was created to codify this purpose. Thus it can be argued that our profession’s perceived duty to the public should make us care about fraud prevention.

Striving for Professional Excellence

In order to begin right in appraising, one must first get the facts right. A popular saying used in the information technology industry is “garbage in, garbage out,” meaning that even the best systems of analyzing information produce flawed results when the data input is flawed. Fraud and deception compromise the data input for the appraisal process. Consequently, what better way is there to start the appraisal process than with a search for the truth?

Not caring to find the truth would be like a master chef not caring about where his ingredients came from. If you asked a master chef about where his mushrooms were picked (hopefully not the public park) or his oysters harvested (hopefully not from underneath the Santa Monica pier), would you respect him for saying, “That’s not my job, but I used all the best cooking methods learned from the finest culinary academy,” or would you instead call the nearest poison control center?

Professional Liability

Many of us as appraisers take pride in being incorruptible guardians of truth and objectivity, earnestly debating ethics at our various meetings and online forums. How incongruous it seems, then, that so many appraisal reports contain the standard exculpatory assumptions and limiting conditions statement, “No responsibility is assumed for the accuracy of information furnished by the client.” This is the fatal weakness of the appraisal profession—acceptance of inaccurate information from biased parties without verification.

Verification can be defined as the act of obtaining evidence that confirms the accuracy or truth of some piece of information. The unconcerned appraiser should be aware of the sobering statistic that failure to verify factual information is one of the six most common reasons that appraisers are sued.1 Even if assumptions and limiting conditions legally exculpate the careless appraiser, that appraiser will still need to employ an attorney for defense if sued.

The recent “just sue everybody” litigation trend will also increasingly reel in appraisers, rightly or wrongly, in future litigation relating to the recent financial industry meltdown, just as we see happening indiscriminately to innocent people who accidentally benefited from the Bernie Madoff Ponzi scheme.

Legal Precedents

There has been a legal precedent for finding appraisers liable for losses caused by failure to verify, as in Federal Savings and Loan Insurance Corporation (FSLIC) v. Texas Real Estate Counselors, Inc.2 In this case, the appraiser was found liable for 1) failing to verify the alleged completion of improvements on the property, and 2) failing to disclose reliance on unverified data when presenting estimates of value and effective age for the subject property.

In Fusco v. Brennan, the Superior Court of Queens County, New York, held that an appraiser’s failure to independently verify the data supplied to him was so negligent that it warranted an inference of fraud, maintaining that the defendant had a duty to all possible investors to inform them of the type and source of data used and the extent of information omitted.3

The same precedent may be exercised by state appraiser regulators. One commercial appraiser was fined $8,000 by the California Office of Real Estate Appraisers for several offenses, one of which was accepting and failing to verify an owner’s assertion that certain swampland had city water and sewers installed on it.

Applicability of a Fiduciary Standard to Appraisers

The applicability of a fiduciary standard to appraisers is a particularly controversial subject. Whether appraisers like it or not, certain case law has presented the concept that an appraiser has certain duties as a fiduciary, or someone who is legally considered to have a special relationship of trust, responsibility, or confidence in his or her professional duties to others. For example, a trust officer at a bank would be a fiduciary.

Fiduciaries are held to higher standards of duty and care and are also more likely to be sued as a result. As this text is being written, for instance, the Appraisal Institute and the American Society of Appraisers (ASA) are lobbying the US government concerning an Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) law that names appraisers as fiduciaries. This lobbying effort is meant solely to reduce legal liability for appraisers and not to reduce the amount of professional care that appraisers should exercise. The matter is not yet resolved, but it only affects entities regulated by the US Department of Labor.

One legal concept of fiduciary responsibility applied to appraisers is the concept of privity, which basically limits parties who can take action against appraisers to only those who are intended users of the appraisal report. If an unintended user, such as an investor, relies on an inaccurate appraisal report to his or her detriment, the concept of privity would prevent that user from suing the appraiser, as the appraiser owed the user no fiduciary obligation.

The concept of privity has generally protected appraisers from lawsuits by property buyers when the appraisal was done for a lender. This concept has recently been reversed, however, in the 2009 case of Sage v. Blagg Appraisal Company4 in Arizona and in the 2010 case of Young v. Bourland in California. Sage sued Blagg after discovering that he had overstated her house’s measurements by nearly 30% in an appraisal done for a lender. The trial court granted summary judgment to the appraiser based on the concept of privity. This was reversed on appeal by the Arizona Court of Appeals, which stated, “Our recognition of the duty owed by an appraiser to the buyer/borrower … is consistent with evolving industry standards that acknowledge that a buyer/borrower in fact relies on an appraisal prepared at the request of the lender.”

In 2010, a California appellate court made a similar ruling in the case of Young v. Bourland, stating, “While the disclaimer contained in [the] appraisal report is evidence that he did not intend third parties to rely on the report and his opinion as to the value of the property, [the borrower] presented evidence from which intent may be inferred. [The borrower]’s name appears repeatedly on [the] appraisal report identified as ‘borrower.’”5

The appraiser should also bear in mind that some purchase contracts, mainly residential contracts, are contingent upon a sufficiently high appraised value, which suggests a buyer’s reliance on an appraisal report done for a lender.

Relevant Cases Establishing Fiduciary Responsibility to Lenders

The increasing use of third-party originators (such as mortgage brokers) in commercial mortgage lending has attracted some unethical appraisers who are acting as advocates for the broker’s clients. Mindful of privity, some may label the intended user of the report as the property owner and the intended use as for “internal management decisions” or “decision-making purposes,” thinking that the concept of privity protects them against actions for fraud by a lender or investor if they do not disclose lenders as a class of intended user.

Case law does not seem to always support such a narrow definition of intended user. In Chemical Bank v. National Union Fire Insurance Company,6 in which appraisers Joseph J. Blake and Associates, Inc., were a third party defendant-appellant, a New York appellate court stated, “If it be shown that a real estate appraiser, retained by a property owner to make an appraisal that he knows the owner will use to obtain financing, makes it in a grossly negligent manner so as to inordinately overstate the value, we are not … prepared to hold the appraiser exempt from liability to the damaged financing party.”

The court cited the principle of law stated in White v. Guarente,7 an action against an accounting firm, stating, “If it were known that it was within the contemplation of the appraiser and the owner when they contracted for the appraisal that a financing party would rely upon it and be persuaded by it, then, since those whose conduct was to be so governed would be a ‘fixed, definable and contemplated group,’ the appraiser would have assumed a duty of care for the benefit of those in the group.8

This case also demonstrates how courts often turn to case law concerning accounting or auditing malpractice in judging appraisers, with the logic that each of these professions produces reports that are relied upon by third parties. Bily v. Arthur Young and Company,9 a case that governs the extent to which an accountant is held liable to third parties relying on his or her report, is sometimes cited. In the case of Soderburg v. McKinney,10 in which the appraiser was found liable for damages to a third-party investor, the following reasoning was provided by the High Court:

Accountants are not unique in their position as suppliers of information and evaluations for the use and benefit of others. Other professionals, including attorneys, architects, engineers, title insurers and abstractors, and others also perform that function. And like auditors, these professionals may also face suit by third persons claiming reliance on information and opinions generated in a professional capacity.

More recently, in the 1999 case of Rodin Properties-Shore Mall N.V. v. Ullman et al., the New York Supreme Court held a commercial appraiser hired by a borrower liable to a lender for a faulty appraisal because the appraiser was aware that the lender would rely on the work product.11 The New York Supreme Court stated, “When a professional … has a specific awareness that a third party will rely on his or her advice or opinion, the furnishing of which is for that very purpose, and there is reliance thereon, tort liability will ensue if the professional report or opinion is negligently or fraudulently prepared.”

In this case, the lender was not federally regulated but was a group of private investors. The Financial Institution Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989 (FIRREA) may prevent an appraiser’s report for a borrower from being relied upon by a federally insured institution, but appraisers should be aware that private lenders or investors operating outside the purview of FIRREA may possibly rely on their reports.

The appraiser in Soderburg attempted to limit his liability by stating in the appraisal report that “reproduction of [the] appraisal report is restricted to such use by the [client].” The extension of privity to the plaintiff investor was only made after evidence was presented that the appraiser knew that the investor would rely on the report.

Professional Standards Found to Imply Fiduciary Responsibility

A fiduciary standard was applied in Guildhall Insurance Company v. Silverman v. O’Boyle,12 holding a jewelry appraiser to the standards of the ASA, of which he was a member. The standards set forth an appraiser’s duties to third parties, thereby relaxing the concept of privity. In 1987, the ASA was among eight professional appraiser associations to collectively found the Appraisal Foundation, which in turn issued USPAP, now considered to be the standard for the appraisal profession in the United States. It is important for appraisers to know that courts may apply USPAP as a yardstick for appraiser misconduct, so it behooves appraisers to stay well-versed in USPAP.

What Is the Expected “Duty of Care” Owed by Appraisers?

Recent court decisions also seem to absolve appraisers of a “duty of care” to third parties except when it could be reasonably expected for the appraisal to be submitted to a lender. In Behn v. Northeast Appraisal Company,13 for instance, the court found no “duty of care” to the seller of a property appraised for a lender. A California appellate court held an appraiser not liable to unaffiliated investors for an appraisal done for a mortgage broker.14

The key issue seems to be whether the plaintiff(s) belonged to a group that the defendant could expect to be influenced by an inaccurate appraisal. An appraisal done for a lender is meant for the institution’s own use, except perhaps in Arizona and California. An appraisal done for a likely borrower could be meant to be used repeatedly to influence private lenders or investors who operate outside FIRREA; it could even be “re-addressed” by a dishonest loan officer at a federally regulated institution. An appraisal done for a syndicator is meant to be used repeatedly in soliciting prospective investors or limited partners.

In prosecuting mortgage fraud, the acid test seems to be whether the appraiser can reasonably expect that the appraisal would be used by a mortgage lender. Even in situations when lenders experience loss as the result of faulty appraisals, appraisers may still be found not to be liable if they can convince the court that they were never told by the client that the report would be used for a lending decision; appraisers can be found to not have privity with lenders. Post-FIRREA, it is unlikely that a regulated lender would make a lending decision on an appraisal report done for another purpose, although it is possible for a previously done appraisal report to get relabeled (illegally) as if done specifically for the lender. Private lenders are not restricted from relying on borrower-ordered reports, however, and if the lender is actually a loan syndicator without any of his or her own equity in the deal, it is quite possible for an inaccurate appraisal to be relied upon by the syndicated investors, who are often unsophisticated investors.

Case Law Concerning Individual Acts of Appraisal Negligence or Fraud

In Rodin Properties-Shore Mall N.V. v. Ullman et al., the appraiser was specifically blamed for 1) stating that Shore Mall was “the principal, fully integrated shopping complex in its primary trade area” and that the only other major regional mall serving the area was 20 miles away, when the competing mall actually dominated the trade area and was only 5.6 miles away, and 2) making exaggerated cash flow projections.15

In Costa v. Neimon,16 the Appeals Court of Wisconsin established that an appraiser was guilty of negligent misrepresentation for mischaracterizing the habitability or functionality of a property. In that particular case, the appraiser described an unfinished basement as being habitable.

In United Insurance Company of America v. B.W. Rudy, Inc.,17 a US district court held that an appraiser’s knowing certification that a newly built apartment building had been completed in accordance with the original specifications was actionable as fraud. In actuality, the building 1) had not been completed to the required size, 2) had improper structural framing, 3) had improper roofing, 4) lacked proper flashings and copings, 5) had improperly installed doors, windows, and sills, 6) lacked proper caulking, 7) lacked proper heating, 8) lacked proper concrete, and 9) did not have the proper air conditioners or the structural provision for their installation. These cases suggest that an appraiser who performs an incomplete property inspection could end up in court.

Improper sales comparisons can also instigate actions against an appraiser. For example, the federal government filed suit against several appraisers and realtors in the collapse of Butterfield Savings and Loan in California for inflating the appraised values of marginally useful properties, such as swamps and forest preserves, by comparing such parcels with sales of more useful properties.18 A similarly inaccurate comparison was cited in the previously mentioned $8,000 fine by the California Office of Real Estate Appraisers against an appraiser for “the selection of inappropriate sales comparables and misrepresentation of relevant property characteristics of the comparable sales.”19

USPAP and Fraud

As was seen in the Guildhall decision, attorneys will turn to the generally accepted standards of the appraisal profession in order to find blame against an appraiser. Today that standard is USPAP.

USPAP requires the appraiser to identify the intended use for an appraisal assignment’s report, apply a scope of work that is appropriate for that intended use, and clearly disclose in the report the intended use and scope applied. USPAP further requires the appraiser to identify the intended users of the report, ensure the report is understandable to those intended users, and clearly state in the report the identity of those intended users. In addition, USPAP has specific requirements regarding the use of hypothetical conditions and extraordinary assumptions. Failure to take these critical steps is not only a violation of USPAP but also can result in a misleading report. In cases in which appraisers have been implicated in fraud, those appraisers failed to meet USPAP’s requirements regarding scope of work, intended use, intended users, and the use of hypothetical conditions and extraordinary assumptions.

The conceivably relevant USPAP standards in the context of frauds being perpetrated today will be discussed in this section. As of the writing of this book, the most recent version of USPAP is the 2010-2011 edition, and all USPAP quotes that appear in this discussion are taken from this edition.20

Ethics Rule

The following are relevant excerpts from USPAP’s Ethics Rule, accompanied by a discussion of how each relates to fraud prevention:

Scope of Work Rule

The scope of work must include the research and analyses that are necessary to develop credible assignment results. Self-interested parties, including an appraiser’s own clients, may try to restrict the scope of work to the detriment of credible and objective assignment results, and an appraiser must tread carefully in such situations so as not to enable fraud. For instance, a client’s refusal to show leases to an appraiser could result in the appraiser performing an inaccurate income capitalization approach.

USPAP’s Scope of Work Rule also commands an appraiser to not allow the intended use of an assignment or a client’s objectives to cause the assignment results to be biased. Self-interested parties seeking loan commissions or tax breaks could instruct an appraiser, for instance, to curtail a property inspection that might bring up troubling vacancy or condition issues.

Standards Rule 1-1

Standards Rule 1-1(b) states, “In developing a real property appraisal, an appraiser must not commit a substantial error of omission or commission that significantly affects an appraisal.” For example, commercial real estate financial losses often stem from a fatal flaw that may not have been considered in an appraisal. Such a flaw might be a lack of water availability or lack of demand for space. These would be errors of omission. Errors of commission might be due to mismeasurement or inappropriate comparison to allegedly comparable properties.

Standards Rule 1-1(c) states, “In developing a real property appraisal, an appraiser must not render appraisal services in a careless or negligent manner.” The legal record suggests that there is a certain minimal standard of verification below which an appraiser may be accused of negligence. In Fusco v. Brennan, the appraiser was accused of being “so negligent as to warrant the inference of fraud.”

Standards Rule 1-2(a) and (b)

Standards Rule 1-2(a) states, “In developing a real property appraisal, an appraiser must identify the client and other intended users.” According to Standards Rule 1-2(b), “In developing a real property appraisal, an appraiser must identify the intended use of the appraiser’s opinions and conclusions.”

As will be discussed later, these two items are important in determining an appraiser’s duty of care to others and may also reduce an appraiser’s legal liability with regard to unintended users or unauthorized use of the appraisal report. One potential issue is the misstatement of intended use and intended user in an effort to avoid legal liability. For instance, would an appraisal performed for a mortgage broker be considered blameless if the intended use is stated as “for the client’s internal decision-making purposes only”? In other words, can appraisers pretend that they have no idea that a mortgage broker would solicit financing with their appraisal reports? The legal record suggests that a court would judge that an appraisal done for a mortgage broker would be likely to be used by a lender for loan underwriting purposes.

Standards Rule 1-2(c)

According to Standards Rule 1-2(c), an appraiser must “identify the type and definition of value, and, if the value opinion to be developed is market value, ascertain whether the value is to be the most probable price in terms of cash.” Actions against appraisers sometimes happen when the appraiser is instructed to estimate something other than market value, but investors and the public may have not read the report to understand that another concept besides market value is being used. One classic example is Gibson v. Credit Suisse, which will be discussed later in this chapter.

Standards Rule 1-2(e)(v)

Standards Rule 1-2(e)(v) states that appraisers must “identify the characteristics of the property that are relevant to the type and definition of value and intended use of the appraisal, including whether the subject property is a fractional interest, physical segment, or partial holding.” This would suggest that an appraiser might get in trouble for appraising a property as a whole without disclosing or adjusting for a partial interest. The appraiser may also be at risk for making adjustments proportional to the partial interest without applying discounts for impaired marketability.

Standards Rule 1-2(f) and (g)

Further requirements for appraisers under USPAP Standards Rule 1-2(f) and (g) are to identify any extraordinary assumptions or hypothetical conditions necessary in the assignment. USPAP defines an extraordinary assumption as “an assumption, directly related to a specific assignment, which, if found to be false, could alter the appraiser’s opinions or conclusions … Extraordinary assumptions presume as fact otherwise uncertain information about physical, legal, or economic characteristics of the subject property; or about conditions external to the property, such as market conditions or trends; or about the integrity of data used in an analysis.” A hypothetical condition is defined as “that which is contrary to what exists but is supposed for the purpose of analysis. Hypothetical conditions assume conditions contrary to known facts about physical, legal, or economic characteristics of the subject property; or about conditions external to the property, such as market conditions or trends; or about the integrity of data used in an analysis.”

Appraisers often confuse extraordinary assumptions with hypothetical conditions and can get into trouble this way. For instance, one misleading appraisal report stated that the appraiser had made an “extraordinary assumption” that a finished street led to the subdivision being appraised. A field inspection revealed no street to be present. As the property was being appraised “as is,” the appraiser misused the term extraordinary assumption, which refers to something the appraiser believes to exist. In this case, the appraiser should have used hypothetical condition, as he knew that the street did not exist. In any event, even if the appraiser correctly described the missing street as a hypothetical condition, he could still conceivably be accused of creating a misleading report, since it was being circulated to subdivision lenders, and many loan officers do not know where to find hypothetical conditions in appraisal reports. The upcoming discussion of the Gibson v. Credit Suisse case will serve as an example of the use and disclosure of hypothetical conditions being considered insufficient to prevent an action for fraud.

Standards Rule 1-3(b)

According to Standards Rule 1-3(b), an appraiser must, “when necessary for credible assignment results in developing a market value opinion … develop an opinion of the highest and best use of the real estate.” The biggest area of risk here is that the highest and best use may have changed due to recent events. In recent history, millions of acres of agricultural land were rezoned for residential or even commercial development and values increased tenfold as initial development projects quickly sold out. Nowadays, with the collapse of the housing market and some commercial markets, an appraiser may be inaccurate in characterizing this rezoned land as continuing to have a highest and best use for subdivision development. A lot of money has been lost by lenders on failed subdivisions.

One example that comes to mind was the appraisal of a cattle pasture 17 miles outside the closest community, a small town with a median household income of only $18,000 per year. Appraising the ranch as a potential residential subdivision would be misleading, despite the existance of a final map of the subdivision by the local county government.

Highest and best use: Residential subdivision or land for cattle grazing?

Standards Rule 1-4(c)(iv)

Standards Rule 1-4(c)(iv) states, “When an income approach is necessary for credible assignment results, an appraiser must base projections of future rent and/or income potential and expenses on reasonably clear and appropriate evidence.” An appraiser must be careful not to rely on self-serving pro forma cash flow projections presented by developers or borrowers. There must be independent confirmation of market trends relating to rental rates, vacancy rates, and increasing expenses in order to have an objective appraisal.

Standards Rule 1-5(a)

According to Standards Rule 1-5(a), “When the value opinion to be developed is market value, an appraiser must … analyze all agreements of sale, options, and listings of the subject property current as of the effective date of the appraisal.” I emphasize the word analyze because the appraiser needs to do more than simply report the price; the appraiser should also determine if the purchase price is a reliable or unreliable indicator of market value. Purchase contracts are often constructed to be misleading, and the appraiser needs to look beyond the price stated at the top of the contract to ferret out concessions or inconsistencies with other documents, such as the previous listing. In one case, an appraiser failed to catch that the purchase price was twice the amount of the listing price, which would have been unlikely for an old warehouse building in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Purchase contract fraud will be explained later.

Standard 2

Finally, USPAP Standard 2 states, “In reporting the results of a real property appraisal, an appraiser must communicate each analysis, opinion, and conclusion in a manner that is not misleading.” If an appraiser has been asked to use an unusual definition of value, hypothetical condition, or extraordinary assumption, it would be best to very prominently disclose the departure from expectations. Even then, the appraiser should consider the following possibilities:

This is indeed the case in the Gibson v. Credit Suisse case to be discussed in the next section of this chapter.

Extraordinary Assumptions Are Not Necessarily a Safety Valve

When the appraiser lacks information needed to proceed with the appraisal process, either the missing information must be obtained or the appraisal process must be completed on the basis of an extraordinary assumption about that missing information. For example, if the appraiser suspects that the property may suffer some type of damage but does not have information that proves or disproves that suspicion, the appraiser might be able to obtain that information, such as in the form of a report by a qualified expert that verifies the absence or presence of such damage and its extent. If not, the only way the appraiser can complete the assignment is by basing the appraisal on the extraordinary assumption that there is no such damage. Such extraordinary assumptions must be clearly and prominently spelled out in the report to satisfy the intent of USPAP.

Such explicitly stated extraordinary assumptions may comply with USPAP, but an appraiser also needs to be mindful that anybody can sue anybody in the United States. Rightly or wrongly, an appraiser may still be sued for not considering the impact on value of a property detriment that he or she did not know about. The appraiser may very well win the lawsuit, too, but at the cost of expensive legal representation and overall aggravation. In other words, the use of extraordinary assumptions is only partial protection.

Conclusions about USPAP and Fraud

The purpose of USPAP is to maintain public trust in professional appraisal practice. One method of maintaining this trust is to prevent misleading appraisal reports. If an appraiser knowingly or unknowingly bases an appraisal on information that can be demonstrated to be false, there may be risk of a civil action for fraud or negligence or, worse yet, a criminal action.

Current Actions against Appraisers

The following cases are not fully adjudicated and are presented for instructive purposes only. Understand that in a court of law in the United States, a defendant is presumed to be innocent until found guilty or liable, and that some current actions against appraisers may lack merit.

The Credit Suisse Resort Loans Syndication21

Cushman & Wakefield (C&W), a national appraisal and real estate services firm, is currently being sued for $24 billion as a co-defendant in a class action lawsuit against Credit Suisse (CS), Switzerland’s second largest bank.22 In 2004 CS started a syndicated loan program backed by 14 of America’s most famous resorts, such as Yellowstone Club in Montana and Turtle Bay in Hawaii (the setting of the movie Forgetting Sarah Marshall). A syndicated loan is a loan sold off to multiple investors. CS collected millions of dollars in brokering and servicing fees on these loans while retaining little or no equity in the securitized loans. Their profits were therefore based on the size of the loans rather than the soundness of the loans, giving the bank the incentive to inflate appraised values.

The alleged loan fraud is described by Bankruptcy Court Judge Ralph Kirschner as follows:

In 2005, Credit Suisse was offering a new product for sale. It was offering the owners [developers] of luxury second-home developments the opportunity to take their profits up front by mortgaging their development projects to the hilt. Credit Suisse would loan the money on a non-recourse basis, earn a substantial fee, and sell off most of the credit to loan participants. The development owners would take most of the money out as a profit dividend, leaving their developments saddled with enormous debt. Credit Suisse and the development owners would benefit, while their developments—and especially the creditors of their developments—bore all the risk of loss. This newly developed syndicated loan product enriched Credit Suisse, its employees, and more than one luxury development owner, but it left the developments too thinly capitalized to survive. Numerous entities that received Credit Suisse’s syndicated loan product have failed financially, including Tamarack Resort, Promontory, Lake Las Vegas, Turtle Bay, and Ginn [Sur Mer].

CS hired the appraisal firm to appraise each resort according to an unorthodox methodology known as “total net value” (TNV), which basically ignores the time value of money in estimating the present value of each of these resort developments. The developments were going to take years to sell out, but future revenues were not discounted for time. The TNV methodology merely subtracted the costs of development without respect to the timing of revenues. It was tantamount to creating discounted cash flow models with 0% discount rates.

Investors naturally expect to be paid a rate of return for deferred profits, so the TNV methodology did not come close to any commonly accepted definition of market value used in the United States. Its sole purpose seemed to be to inflate the appraised value to justify a higher loan amount.

The appraisal firm performed the appraisals according to the TNV methodology dictated to them by the lender and attempted to cover themselves with all the necessary disclosures, assumptions, and limiting conditions in their reports. Others who did not view the reports mistakenly thought that the appraisals were market value appraisals.

All 14 syndicated loans failed and property owners at four of the failed resorts—Yellowstone Club, Tamarack Club in Idaho, Lake Las Vegas, and Ginn Sur Mer in the Bahamas—filed suit against CS and the appraisal firm, claiming that 1) CS had defrauded them with a predatory “loan to own” scheme, 2) appraisers had used the TNV methodology to create misleading and deceptive appraisal reports that violate FIRREA, and 3) the defendants, knowing this, engaged in a conspiracy to circumvent FIRREA by creating a special-purpose lending entity in the Cayman Islands and having the appraisal reports delivered there. The CS Cayman branch was alleged to be a post office box.

In its motion to dismiss, the appraisal firm claimed that the plaintiffs were aware that the appraisal reports properly disclosed that they were not estimates of market values. They also pointed out that there was no connection between the plaintiffs and the appraisers and thus no basis for privity, stating, “There is no basis for concluding that C&W could have intended that plaintiffs rely on an appraisal not prepared for them.” The motion to dismiss, interestingly enough, also states that the appraisals’ noncompliance with FIRREA was irrelevant to any of the loans because the lender was from the Cayman Islands.

The complaint makes no reference to USPAP but does refer to violations of FIRREA. Interagency appraisal guidelines, for instance, require that an appraiser “analyze and report appropriate deductions and discounts for proposed construction or renovation, partially leased buildings, non-market lease terms, and tract developments with unsold units.”23 A discount rate of 0% would not meet the standard for an “appropriate discount.”

The Yellowstone Club example illustrates the magnitude of appraised value inflation as a result of the TNV methodology. Yellowstone Club is a private vacation home community in Montana that includes such notable residents as Bill Gates and Dan Quayle. Prior to CS’s involvement, the same appraisal firm had appraised Yellowstone Club for $420 million. CS instructed the appraisers to revalue Yellowstone Club several months later using TNV methodology, and the appraised value shot up to $1,165 million, supporting a $375 million loan decision by Credit Suisse. The loan later went into default and foreclosure.

On July 17, 2009, the foreclosed Yellowstone Club was sold for $115 million to Cross Harbor Capital Partners. The loan loss was therefore about $260 million. On January 17, 2011, US Magistrate Judge Ronald E. Bush ruled that the class action plaintiffs could proceed with their lawsuit against the appraisal firm based on claims of negligence and conspiracy.

Judge Bush provided the following instructive remarks:

Without Cushman & Wakefield’s appraisals, there is no “loan to own” scheme from which plaintiffs can premise their claims … The unusual nature of Cushman & Wakefield’s TNV appraisals can further be inferred in Plaintiffs’ favor to support its participation in a RICO enterprise, recognizing that they appear to have been created to obtain the highest possible dollar value for the uncompleted developments, resting primarily on forecasted, not yet realized, net cash flow streams, but without discounting the net cash flow back to a present value.

Nevertheless, the judge dismissed the RICO claims. (RICO stands for the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act of 1970, a federal law originally intended to combat organized crime.)

In terms of the disclosures, disclaimers, and limiting conditions prominently displayed in the appraisal reports, the judge stated:

Cushman & Wakefield may technically be correct in arguing that the appraisals’ language insulates it from any claim that the appraisals somehow represent bogus market values. Such an argument assumes, however, that a reader negotiating the appraisals’ provisions understands (or should have understood) the quoted language to mean what Cushman & Wakefield and/or Credit Suisse understood it to mean. At the moment, it is unclear what the developers/homeowners understood these figures to represent—assuming they even read them in the first place. Did the referenced appraisal amounts reflect cash flow analyses? Total net values? Total net proceeds? Or something else? Separately, whatever it is, what is the difference between that and market value? Although it is indeed possible to view the appraisals’ language through the lenses of Cushman & Wakefield’s arguments, the Court must consider the limited record before it and accept Plaintiffs’ allegations as true.

The judge refused to dismiss claims against the appraisers, rejecting the privity argument on the grounds that the plaintiffs were pursuing a claim that they were victims of a conspiracy enabled by the appraisers and thus had the right to have their allegations heard. This should not be interpreted as a finding of guilt, however.

Lessons to Be Learned

Some appraisers may think that liberties can be taken in an appraisal report as long as they are prominently disclosed. Appraisers may agree among themselves on what these types of disclosures are, but those outside the appraisal profession may not understand disclosures when they see them. The Credit Suisse case may test the limits of how far this possibly undue reliance on disclaimers can go.

The complaint against the appraisers is emblematic of a surprising new trend in litigation against commercial appraisers, which is to charge the appraiser with aiding and abetting a lender’s “predatory lending” or “loan to own” scheme. There is insufficient case law to judge the likely outcome of these lawsuits.

The appraisal reports for CS were previously published on the Internet and contained standard disclosures, disclaimers, assumptions, and limiting conditions. The “intended use” was for loan underwriting and the “intended user” was CS. An appraiser reading these reports could reasonably infer that the appraised values were not labeled as or intended to represent market values. The plaintiffs in this case would not normally be considered to have a claim based on privity, either. Nevertheless, the appraisal firm is still facing a $24 billion lawsuit after an unsuccessful motion to dismiss.

Judge Bush has raised the question of whether the plaintiffs properly understood the reports or had such capability. This raises the question of whether disclosures, assumptions, and limiting conditions are enough to prevent the public from being misled. Appraisers should consider that any number printed as an “appraised value” is likely to be interpreted by others as an expression of market value. Many persons, including loan officers, may rely on an “appraised value” without reading the report and finding the disclosures. Some properties or projects are even marketed with representations of appraised value without ever allowing the public to see the supporting appraisal reports, as was the case with Credit Suisse.

Large firms, in this case a national brokerage and appraisal firm, have deep pockets that can serve as a target for lawsuits. It would be in such a firm’s best interest to avoid all situations allowing accusations of impropriety. In this case, the reason for using TNV methodology instead of market value was not explained, making it seem that TNV’s sole purpose was to inflate the appraised value. This may make the appraisers seem complicit in the alleged loan fraud by CS, which the appraisals enabled. It is questionable if the appraisers expected to be part of a syndicated loan fraud scheme, however, as the only benefit to them was the fees earned for the reports. Nevertheless, whistleblower Michael Miller at C&W has come forward with allegations and incriminating e-mail messages (one of which included “not in jail yet and continuing to write these appraisals”) indicating that his colleagues knew they were creating misleading appraisal reports.

The final lesson to carry away from this case is that appraisers should consider the reasons and consequences any time they are asked to apply unorthodox and possibly misleading appraisal methodology.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation vs. The Appraisal Profession

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) is a federal agency charged with insuring deposits at depository institutions. They also act as financial regulators and legal receivers of the insolvent lending institutions that they seize.

The FDIC’s actions against appraisers have been described by some as a systematic shakedown of the appraisal profession. In the first eight months of 2010, the FDIC named 17 individual appraisers as defendants in lawsuits.24 In June 2011 the FDIC filed suit against 89 appraisers within the state of Florida with regard to the failure of Washington Mutual. What is far more common, however, are demand letters sent to appraisers connected with any loss to the FDIC, such as the letter in

Exhibit 2.1.

All FDIC complaints against appraisers have been for overvaluation. These letters may perhaps only be “fishing expeditions” to see if the appraiser will admit wrongdoing or have his or her liability insurer cover the loss. It has been alleged that in some cases, the loan loss may not have had anything to do with the appraisal but was instead due to fraud of another kind or a market downturn. However, in the case of a first payment default as described in Exhibit 2.1, appraisers look bad when the foreclosed property cannot sell for a price equivalent to the very recent appraised value.

Current FDIC litigation against appraisers that is searchable online includes FDIC v. JSA Appraisal Services (California), FDIC v. Anoka Appraisal Services (MN), FDIC v. Long Island Appraisal Network, Inc. (New York), FDIC v. Behr Residential Appraisal Group (IN), FDIC v. Quest F.S. et al. (California), FDIC v. LaMarsh Financial et al. (California), and FDIC v. M&M Appraisals et al. (California).

Lending Institutions as Plaintiffs

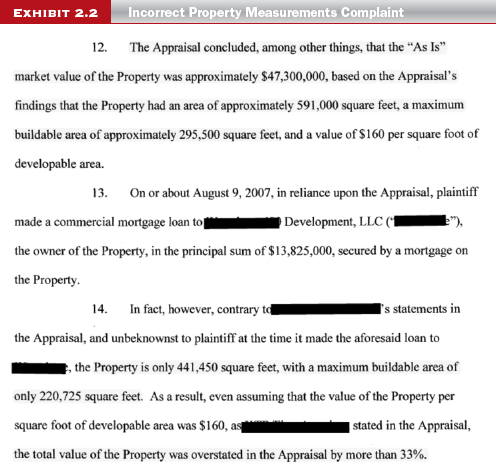

Exhibit 2.2 shows a formal complaint against a commercial appraiser who apparently relied on incorrect measurements for the appraised building.

Source: Peter Christensen, Fall 2010 Appraisal Summit.

Conclusions to Be Deduced from the Legal Record

Appraisers are sometimes asked to perform appraisals according to subjective criteria, such as the use of hypothetical conditions, extraordinary assumptions, or unorthodox methodology. Appraisers may think they are protected from liability by making prominent disclosures and disclaimers and stating any limiting conditions in their reports. The legal record suggests that such disclosures may not always be sufficient to avoid legal liability or, at the very least, an opportunistic lawsuit. An appraiser might also mistakenly think that all the caveats placed in a misleading report would automatically exclude it (per FIRREA) from consideration by a lending institution, not realizing that a private lender might rely on the report instead or that a mortgage broker or loan officer may repackage and relabel the report for a regulated lender, even illegally, as I have personally witnessed in my banking career. An appraiser’s estimate of value may also be used by an unscrupulous person trying to capitalize on the appraiser’s reputation, such as advertising “Appraisal Firm X has appraised the property to be worth X amount of dollars.” Others may rely on the estimate of value without being able to read the report and all of its disclaimers.

The best recourse may be to just refuse any appraisal assignment that does not seem honest. If the appraisal assignment must be done, however, the report should prominently state that its purpose is for a specifically intended use and intended user and no others and should prominently disclose the assumptions and limiting conditions that apply to the value conclusion, such as, “This appraisal was done for a developer for capital planning purposes. The conclusion of ‘aggregate retail value’ reached in this report is not to be interpreted as a representation of market value, which would be less due to discounting to reflect the rate of sales absorption and the time value of money.”

The important concepts here are that the report must not be misleading and should also warn the unintended user to not rely on the report or expect a fiduciary duty from the appraiser. Even then, such disclosures and disclaimers are no guarantee of safety from lawsuits, as we have seen in Gibson v. Credit Suisse. My personal advice is to think twice—no, think three times—before accepting an appraisal assignment to deliver appraised values that differ from market values.

Future Actions against Appraisers

Appraisers should be aware that there are law firms that specialize in suing appraisers, some of whom have been retained by the FDIC. Berk and Moskowitz, for instance, is the Arizona firm that prevailed in the Arizona appellate court decision erasing privity as a defense for lenders’ appraisers against lawsuits by homebuyers. More can be learned on their website, www.appraisernegligence.com.

Conclusion

A great financial crisis has recently occurred, and the process of finding scapegoats is just getting started. As a result, many lawsuits have already been brought against appraisers. An appraiser may become a target for a fraud lawsuit even if he or she was unknowingly complicit in a fraud committed by someone else. This is perhaps the most compelling and self-serving reason why fraud should matter to appraisers: because appraisers can be blamed for fraud, even if it happens without their knowledge.

1. LIA Administrators & Insurance Services, www.liability.com.

2. FSLIC v. Texas Real Estate Counselors, Inc., 955 F.2d 261 (5th Cir. 1992).

3. New York Law Journal 13 (January 1982).

4. Berk & Moskowitz, PC, Attorneys at Law, www.appraisernegligence.com.

5. Presentation by Peter Christensen, Fall 2010 Appraisal Summit.

6. 74 A.D.2d 284, 502 N.Y.S.2d 165 (1st Dept. 1986).

7. 43 N.Y.2d 356 (1977).

8. Chemical Bank, 74 A.D. at 787.

9. 3 Cal.4th 370, 376.

10. 44 Cal.App.4th 1760, 52 Cal.Rptr.2d 635.

11. FindLaw website, www.findlaw.com.

12. 688 F. Supp. 916 (S.D.N.Y. 1988).

13. 483 A.2d 604 (Vt. 1984).

14. Christiansen v. Roddy, 186 Cal. App. 3d 780, 231 California Reporter 72 (1986).

15. FindLaw website, www.findlaw.com.

16. 366 N.W.2d 900 (Wisconsin Court of Appeals 1985).

17. 42 F.R.D. 398 (1967).

18. Statement of William K. Black before the House Subcommittee on Commerce, Consumer and Monetary Affairs, 100 Congress, 1st session 10 (1987).

19. California Office of Real Estate Appraisers, Details of Licensee 021394, www.orea.ca.gov.

20. Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, 2010-2011 ed. (Washington, D.C.: The Appraisal Foundation, 2010), pp. U-3–U-21.

21. Gibson et al. v. Credit Suisse et al., US District Court Idaho, Case no. 1:10-cv-00001-EJL.

22. Jim Robbins, “Credit Suisse Is Accused of Defrauding Investors in 4 Resorts,” The New York Times (January 4, 2010).

23. Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Interagency Appraisal and Evaluation Guidelines, www.fdic.gov/regulations/laws/rules/5000-4800.html.

24. FDIC Reporter, August 20, 2010.