A host of unfavorable property characteristics can be misrepresented by property owners. The commonly misrepresented conditions that we will discuss in this chapter are:

Legality of Use

An illegal use—a use that is contrary to zoning laws or building and safety codes—can be discovered by local authorities, who might then force the owner to remove the improvement and/or pay for the conversion of the space back to a legal use. This can often lead to financial loss for the buyer or lender.

One particularly memorable example is a scam carried out in the early 1990s. A New York City walk-up apartment building on a residential street was acquired by three phony doctors who claimed that they had the permits to remove all ground-floor, rent-controlled tenants and replace them with an MRI facility. There was no such zoning variance approved by the city, but the appraiser never checked for zoning or permits and used MRI facility rent comparables justifying a much higher potential income for this rent-controlled residential building. The purchase loan went into immediate default, at a major loss to the lender.

Unknown to the appraiser, these same three “doctors” also acquired another walk-up building in Greenwich Village with an above-market, “pocket-to-pocket” lease with a natural foods store they wished to operate in a hard-to-rent basement space, and this lease was used to support a purchase price well above the building’s market value. This purchase loan also went into immediate default. Legality can often be verified online or with a recent certificate of occupancy or a phone call to the city’s building department, steps the appraiser in this case most likely didn’t take.

Some appraisers may argue that lax code enforcement has caused some buyers to pay full price for illegal improvements, thus requiring them to give full value to such illegal improvements. This could get an appraiser into trouble, though, as unexpected future enforcement of city codes could jeopardize these illegal uses and cause a loss to the buyer or lender. All it takes is one major fire or loss of human life to change the political climate for code enforcement. So the unit is unheated? What will happen to local code enforcement when a tenant freezes to death in another unheated apartment elsewhere in the city?

Be alert to clues of illegal improvements. For instance, a studio apartment without a thermostat in a building with central heating and cooling could actually be a master bedroom that was walled off from another two-bedroom apartment. Some landlords do this because they can get more rent from a one-bedroom apartment and a studio combined than they could from a two-bedroom apartment alone. Abrupt changes in a roof line or exterior cladding (i.e., one type of material covering another) could also be signs of an illegal addition.

As verifiable as it is, even a property’s zoning can be misrepresented. For example, a landowner in south Florida who wished to build a community shopping center claimed commercial zoning. Checking with county officials, the appraiser found that the parcel actually had agricultural zoning with a designated future land use of commercial, but the only commercial use the county government intended to approve for the subject site was use as a warehouse.

When in doubt, talk to the local government departments that make the rules. In all of these cases, of course, a properly performed highest and best use analysis could have averted trouble.

Availability of Utilities and Water

Some owners of land that does not have access to fresh water or sewers may try to hide this fact. The availability of utilities and water on a property needs to be verified with the relevant municipality or private utility company. In one case in Lake Elsinore, California, the owner’s misrepresentation of water and sewers caused an appraiser to appraise a raw land parcel—that was acquired nine months previously for $236,000—at $16 million. Property owner claims of receiving water or sewer service “any day now” also need to be verified.

The owner of this property claimed that the property had city water and sewers installed on it when in reality it was a Flood Zone A property with limited usefulness. The abrupt change in vegetation at the lower elevation is an indication of a high water table.

Water rights can be very important for appraisers in western states. For example, one property owner claiming to have rights to a large, underground aquifer with many potential users instead had rights to an underground stream that was only available to a few other potential users. Water rights tend to be less valuable in thinly traded markets, particularly when the pace of land development has subsided, as has happened recently. Water rights can typically be verified by an engineer who works for the state’s department of water resources.

Property Size

The larger the building, the harder it is to verify building area. Relying on rent rolls or landlord claims of property size can be risky.

A 17,000-sq.-ft. warehouse in Philadelphia, for instance, was appraised as a 22,000-sq.-ft. warehouse. When he was asked to explain this discrepancy, the appraiser said he knew the warehouse was 22,000 square feet in area because the rent roll said so.

Property managers sometimes create more rentable area than there is building area. For instance, regional mall managers have been known to brag about their ability to create extra rentable area out of thin air. Twenty-five years ago, when tenants would discover a discrepancy and protest that they were paying for too much space, the mall manager would simply say something like, “We’re at full occupancy here. You can either keep paying the same rent or else we’ll find someone else who will.”

Today in the United States and elsewhere, many regional malls are in a different negotiating position, due to escalating vacancies and struggling retailers. A savvy tenant (such as a major retail chain) may audit the amount of space and be able to negotiate the rent downwards or sue the landlord for years of overpaid rent.

Architectural building plans can be more reliable in indicating building area but may not reflect change orders that could have affected the area. Public records are objective but can often be inaccurate. Public records often understate building area due to unrecorded, but permitted, additions as well as local customs that exclude certain types of building area, such as basements. Basements are inherently less valuable than ground-level space but can still have value if they bring in rental income.

Property Measurements

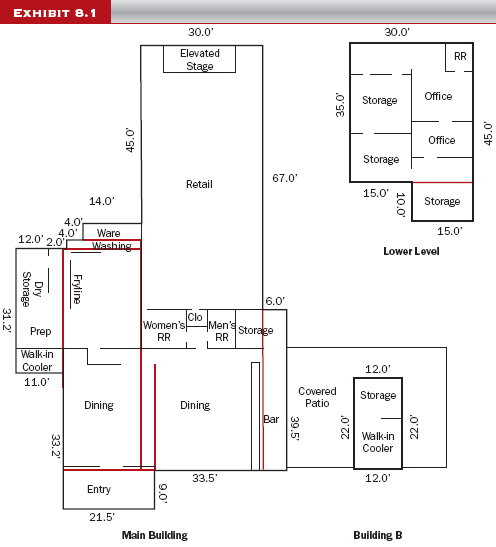

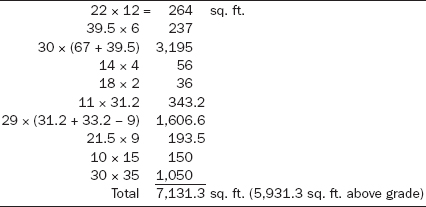

By process of elimination, then, the best way to verify building area is to measure it. This is not always easy. For buildings with irregular areas, one trick to simplify the task of measuring is to draw a building sketch, divide the area into rectangles, and then add up the areas of the rectangles, as shown in Exhibit 8.1.

The building area for the property shown in Exhibit 8.1 can be divided up into ten rectangles, as follows:

For a particularly complex assignment, an appraiser may even want to subcontract property measurement to a commercial property inspection firm.

Property Condition

Although the condition of the property is somewhat obvious at the time of inspection, the severity of the deferred maintenance can often be understated. Non-functioning equipment, particularly elevators, may be permanently rather than temporarily disabled. If your client is a lender, it is best to have the client order an expert inspection for any valuable building components, such as elevators, HVAC systems, or even kitchen equipment.

Some owners may contend that major renovations have occurred since they acquired the property, even though the renovations may not be evident. For example, one apartment landlord in Tulsa claimed to have made $350,000 in recent renovations, but the property still had shag carpets, appliances, and HVAC units that dated back to the 1970s. What had actually happened was the previous owner had made a $350,000 cash reduction in the sale price for a “renovation allowance.” However, since this was not a cash allowance but a cash reduction of the purchase price, the money was never spent. When in doubt, politely ask to see receipts for the renovations.

Transferability of Rights or Funds

Sometimes a property owner holds extra rights that may add to his or her own value-in-use of the real estate, such as:

An appraiser needs to determine the transferability of such special rights by examining the source documents that allow the transferability. A right may create great value for the existing property owner but may not be available to subsequent owners of the same property. If a right cannot be transferred, it has no market value.

For example, the city of Monument, Colorado, granted lucrative tax exemptions to a developer for the specific purpose of building a water park. Although the parcel was being purchased for about $20 million, a local appraiser appraised the land for $80 million by adding $60 million in anticipated tax savings. No one argued that $60 million in tax savings was possible, but the city ordinance declaring the tax exemptions specifically stated that the tax exemptions were not transferable. A city official explained, “Why should we allow the exemption to be transferred to someone who doesn’t need it, like Wal-Mart or Home Depot?”

Community redevelopment agencies often create subsidies for developers to undertake projects in underdeveloped areas, which are euphemistically relabeled as “redevelopment areas” or even “arts districts” or “theater districts.” These “project funds” often come with many conditions as to use, density, or aesthetics. Some developers then approach lenders offering these project funds as additional collateral, but appraisers need to determine:

Too often, the answer to these questions is “no.”

There are also situations in which the subsequent owner would be made liable for repayment of project funds extended to the previous owner. City agencies use such language to ensure that project funds get paid back if the project is not erected as planned.

Tax Credits

Some redevelopment projects may be eligible for federal and state tax credits, such as the federal “new markets,” “historical preservation,” or “low-income housing” tax credits that offset federal income taxes. However, care should be taken to establish that these tax credits have already been awarded, as tax credits are often competitively allocated and limited in supply. For instance, less than 25% of applicants for “new markets” tax credits (that encourage qualified investment in economically challenged communities) are successful in gaining the credits.

Some developers claim value for imminent historic tax credits before their buildings are officially registered as historic structures. In one case, a developer claimed to have historic and (state) theater tax credits for a 1950s-era office building on the grounds that he intended to convert the building to a parking garage for a historic theater one block away. No tax credits had been awarded, and there were no architectural drawings, plans, or specifications to support the intended renovation.

A developer prematurely claimed to have historic and theater tax credits for this 1950s-era office building because he intended to convert it to a parking garage for a nearby historic theater.

Water Rights

In the western United States, water resources (river water, lake water, or groundwater) are usually rationed. Water rights can usually be sold, but one must be careful to identify what the exact water rights are and who can practically use them.

For instance, groundwater rights are quite valuable in the Reno metropolitan area and can be transferred to potentially hundreds of other users with access to the underground aquifer.

A golf course near Reno was represented as having substantial water rights, presuming that these rights had the same value as Reno-area groundwater rights, but the engineer’s report indicated the water sources to be surface and underground mountain streams shared by few other property owners. The market value of these water rights was substantially less than the value of groundwater rights because the market for these rights was so much smaller. These stream water rights could only be practically used by the few other landowners along the streams.

Other factors that also go into the valuation of water rights include “priority date” (seniority), season of use, location of the water source, and water quality.

Bond Financing

“I don’t have to pay back the bond money,” developers will often claim. In one case, a promise of up to $100 million in bond financing for the developer was made by the town council of a small, low-income Delaware town of less than 4,000 residents. The developer was supposed to build 2,384 new “senior townhomes” (restricted to those who are at least 55 years old), and the bond payments were to be made by special assessments paid by the eventual new residents of this massive town addition. The appraiser assigned a present value of $41,500,000 to this “free money,” which was roughly twice his estimate of the real estate value alone.

The council of a small, low-income Delaware town promised up to $100 million in bond financing to a developer, who was supposed to build over 2,000 new senior townhomes on this plot of land. The money was supposed to come from special assessments paid by future residents of the townhomes. The appraiser assigned a present value to this bond financing that was almost twice the real estate value.

Special assessment bond financing is often a zero-sum game, however. Experience has shown that homebuyers discount their purchase offers by the amount of the extra bonded indebtedness because of the extra monthly payments they will make.

In California, many subdivisions have been built with “Mello-Roos” bonds requiring residents to pay extra special assessments. The term “Mello-Roos” comes from the names of the coauthors of the Community Facilities District (CFD) Act, which allowed these special districts to be established with the stipulation that the homeowners who live in the districts re-pay the money used to fund the community’s infrastructure.1

Competing California subdivisions often use the phrase “no Mello Roos” in their advertising to attract buyers not wanting to make these extra payments. This phenomenon works the same way in other areas, such as with special assessment districts in Florida and municipal utility districts in Texas. Always remember that a bond has to be paid back. There is a four-letter word in the expression “bonded indebtedness,” and that word is debt.

While there may be a value to public bond financing at rates more favorable than lenders’ rates, one first has to establish that there really is bond financing in place. The Delaware seniortownhome scenario would be a non-starter in today’s bond markets, particularly since the repayment scenario seems so doubtful as to be absurd. Would there even be buyers for such a bond? Assigning value to a bond that has not even been issued is “jumping the gun” and very risky.

Small-town bond financing can be particularly perilous, too, as the bonded indebtedness can be an albatross that sinks the city’s finances. A recent example is the town of Buena Vista, Virginia, population 6,500, which used bonds to finance a golf course development to rescue the town’s ailing economy.2 The bond was to be repaid by profits from the golf course and potential luxury homes, hotel rooms, and restaurants. The golf course failed to be profitable, but the town also put its own city hall building up as collateral for the bond. The town defaulted on its bond payments in the summer of 2010 and now faces the prospect of having its city hall foreclosed on and sold.

Conclusion

An appraiser should verify all property characteristics significantly contributing to value, such as property size, utilities, zoning compliance, the functionality of critical mechanical systems (e.g. HVAC or elevators), the transferability of special rights or funds, or claims of renovations. Owner representations should not be accepted without verification of the property attributes having a major impact on the overall value of the property. A properly conducted highest and best use analysis will also go a long way in preventing some of these frauds.

1. Todd Foust and Charmaine Ngo, “What is Mello-Roos?” Realty Times (July 10, 2009), www.realtytimes.com.

2. Ianthe Jeanne Dugan, “Fight Over City Hall—Literally,” The Wall Street Journal (August 17, 2010), p. C-1.