Introduction

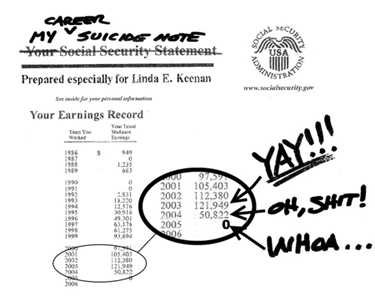

Behold, in graphic detail, the career suicide note of one Linda Erin Keenan. Each year since having my son and having the luxury to stay home with him, the Social Security Administration has quite graciously let me know, with this, my lifetime earnings statement, that after a decade of steady raises at work, I have gone from Hero in 2003, to pregnant and disabled with severe nausea in 2004, to Big Fat Zero in 2005 and beyond. Well, I prefer the term, “Unpaid Mommy, Raising America’s Future,” you woman-hating bureaucrats!

Every year when I find this hateful scrap of paper in the mailbox, I once again see the clearest evidence I have of how I tumbled so hard and fast from a trash-talking, urban CNN news writer in New York City to an unemployed, depressed, suddenly suburban, and still trash-talking stay-at-home mom. I do have an unstoppable potty mouth as you’ll see in this book, and I’m not talking about diaper chat here.

This Career Suicide Social Security Earnings document, in a way, was my ticket into an utterly foreign place I now call Suburgatory, where potty mouths (and minds) like mine are about as rare as black people—in the 1 percent range, I’d say. Actually there are probably more black people than potty mouths, now that I think about it. In this strange land, I had a new baby, no friends, and not much more than a prescription for Zoloft to keep myself afloat. Apparently, the ticket was one-way, because I’m sure as hell still stuck in Suburgatory.

The original proposal for this book was picked by Warner Brothers in 2010, and you can see their imagining of Suburgatory on the ABC show of the same title, which debuted in Fall 2011. But while the TV series focuses on a transplanted teen from New York City, my book offers a vision of suburbia and contemporary American life that I witnessed when I myself was transplanted from the city after having my son. It is satirical local news that skewers mostly upper-middle-class American pieties and parenting obsessions (not least, my own). I also target racism, sexism, mommy wars, body self-hatred, sublimated suburban sexuality, and class warfare; willful ignorance to the broader world along with an America in decline; and the all-around bad behavior that I have seen raging underneath the surface of those obsessively tended suburban lawns and bikini lines.

Do those “isms” make this sound like that annoying late 1980s sociology class you skipped, or worse, a women’s studies course?! Well, fear not, there’s lots of swear words and dirty talk all over Suburgatory. (See later, my combination of both obsessions with the lawns and the bikini lines, in my fake ad for Suburgatory’s new, hot landscaping service: “The Lawnzilian.”)

Tessa, the teenage character created by ABC’s Suburgatory, was forced by the man in her life—her dad—to leave her beloved city life for this supposed suburban utopia, which the show creator says was inspired by her own experience as a teen. As I wrote about in my book proposal, I followed the same trajectory—with my husband, Steve. Steve couldn’t imagine raising our son in New York, which had become too unimaginably scary to him once he gazed upon his new, miraculous baby boy clone. I did not feel this way. But I couldn’t imagine handling my scary-intense job and being a mom at the same time. (Several mom friends could handle it—though not most—it must be said. Sorry, bra-burning, second-wave feminists disgusted with their weak, pathetic daughters! You can ask my weary shrink and pharmaceutical-battered liver: I simply couldn’t cut it.)

OK, here’s the point where you might be thinking of flinging your book or iPad or Kindle across the room, and saying to yourself: Oh my God, I’ve bought another whiny white mommy book. What was I thinking? Here she goes, complain, complain, annoying, spoiled whiny white mommy. I’m toning her! Well, let me explain precisely what this whiny white mommy is complaining about.

I fully acknowledge that I am among the luckiest of women in the luckiest place anywhere on the planet. I chose to stay at home and that’s not a choice most can make. That Big Fat Zero on my Career Suicide Note did not bankrupt me. I made good money for a handful of years, and have a husband with a good salary, and we are also both pathologically cheap.

How cheap are we? So cheap that we could swing living in modest homes in expensive suburbs with great schools. But full disclosure: This luxury was subsidized by money I inherited when both my parents died (by the time I turned twenty-nine). Considering their modest salaries as teacher and career guidance expert in my hometown of Albany, New York (black/hispanic population near 40 percent—take that, whitey-town suburbia!), the fact that they amassed any savings at all after sending three daughters to pricey colleges amazes me. Clearly they were cheap, too—or, to use my technical term, “Super Crazy Mega Cheap.”

My problem, and of course it is a problem only in the upper-middle-class sense of the word, is that abruptly leaving my career for suburban mommyhood made me a foreigner in a place where conformity was king, subversion seemed policed, and where I often felt like I had been taken hostage by an adult Girl Scout troop.

No surprise that my first friends in suburbia were actual foreigners. Naoko and Yuki were my treasured Japanese lady friends who fit in far better than I did, even though they weren’t part of the rich “Power Asian” set, a significant demographic in my new land. “Rinda, this my home now!” Naoko would say, with several kids to take care of and a husband deployed in Iraq (and now, sigh, he’s in Afghanistan. Semper Fi, Kevin Conway.) Still, she somehow found time to scrapbook, and, oh, work overnights at a place where she championed and cared for the severely disabled. What she lacked in language skills, she more than made up for with her indomitable spirit and trays of homemade sushi rolls. I wasn’t the least bit surprised at the strength we all saw after the Japanese earthquake. Not me, not after Naoko and Yuki, who’s a gorgeous beam of steel herself.

But what made me a foreigner? Really, it was my love of the transgressive and the unspeakable, spoken out loud. I’ve always been this way. As a seven-year-old in 1977, I drove my very conservative, Depression-era mother insane after I read the book William’s Doll and began my own tiny fag hag crusade on behalf of “sissies” everywhere.

No surprise, I was the all-purpose outcast of my Catholic school—St. Bully’s of the All Sadists—where my only outlet from constant harassment was to furtively read Judy Blume’s Deenie (the one where Deenie touches her “special place” with a washcloth! God, I’m still aroused thirty years later).

No surprise that my sole childhood friend was the only Jew my Irish Catholic family really knew—Sheryl Olinsky—who set me up for a lifetime of Heeb-lovin’ and Chinese-food eatin’, and whose Barry Manilow and purple-powered Bat Mitzvah was the defining social event of my childhood. Pretty much the only social event, now that I think about it.

And no surprise I ended up in New York, a glorious Jewzapalooza and Homo Heaven rolled into one, working in a place where having an eye for the deranged and twisted was not just tolerated, but a job requirement. For me, my truest home was a network TV newsroom.

Earnest moments are rare for me, and here comes one of them: I felt genuinely grateful, especially after 9/11 at CNN, that in my own tiny deskbound way, writing hermit-like on my bits of anchor copy, I got to call bullshit on asshole thugs on a global scale, on a daily basis. “Oh, I see, crazy Taliban nut-jobs, you plan to tip over a brick wall on top of an ‘accused homosexual?’ Now you’re stoning a thirteen-year-old who was raped because she ‘asked for it’? Allow me to help tell the world how sick and horrible you are!”

And beyond that ample satisfaction, I had the social benefits. I had found a family of trash-talkers like me, and we all relished incidents of guests gone wild. To get a control room full of satellite jockeys, camera guys, and nail-gnawing producers to laugh, you need to bring it hard, like the night when one guest, comedian Bill Maher, discussed basketball player Kobe Bryant “trying to get some stanky on his hang-down. Oh, can you say that on CNN?” Anchor Aaron Brown smoothly said, “I didn’t understand most of those words,” and for a few seconds neither did we as we speed-translated in our heads what the “hang-down” and “skanky” were. (For you nice, innocent types, “getting stanky on your hang-down” means getting a girl to have sex with you, as in “Linda was over last night? Did you get some stanky on your hang-down?”) Once those seconds were up, we began bellowing at the fact that Maher had slipped that tender bit of sweet talk onto CNN air, with no apparent FCC fine either.

Another favorite was no-holds-barred sex columnist Dan Savage. When we booked him as a guest, I remember thinking in the back of my mind, This guy could go X-rated, nasty-nuclear on live air. He was picked to appear after a U.N. weapons inspector and Marine was reported as being an open and active member of the sadomasochistic “community.” In the span of, um, four minutes? Savage hit the following topics: S&M (“sort of cops and robbers for grown-ups with your pants off, and it usually ends in masturbation”), vaginal and anal intercourse, balloon fetishes, smoking fetishes, and plushophiles (folks turned on by stuffed animals, and/or who dress up like stuffed animals. Savage’s advice: “I hope there’s a lot of Scotchguarded fabric on it.”). He closed the interview by saying “Personally, I haven’t spanked a Marine, but I would make an exception for this man if I could see him first.”

No one went ballistic about Maher’s “stanky hang-down,” but I think Savage’s bravura performance almost got a few of us fired.

There were also moments of sublime retribution: When we, the lowly staff, saw our own private Ron Burgundys—the most imperious of anchors—humbled. Some were famous, or, more annoying still, wannabe famous. These are things that never ended up on Page Six in the New York Post, but damn well should have. (I should add that I have worked with or around dozens of anchors and reporters at three different news organizations. Good luck trying to figure out who I’m talking about. To tease you further on this, see the “Toddler or Anchor” piece later in the book, satire that’s actually all true. And to the many nice, normal anchors or reporters? Know that your staff worships you for your sanity.)

A favorite was when one particularly annoying gasbag anchor left his wallet in the bathroom. Inside was a topless photo of his socially prominent, flat-chested girlfriend. (Is there any socially prominent woman who isn’t flat-chested? And what about the booty? No booty either? Is there any preppy person with a booty?) That image got photocopied, by the way. Lucky for them this was back in the day, well before bare, semifamous A-cup titties would go viral within minutes. In any case, Sorry socially prominent, flat-chested, booty-free girlfriend. That’s what you get for dating a pompous ass who can be nasty to his staff. A bumbling pompous ass who loses his wallet. He’s booty-free too, by the way.

And there are few things sweeter than seeing the anchor who just humiliated your beloved work friend having his bald spot spray-covered with Hair-In-A-Can after the previous application of “hair” melted off in the rain. Or hearing a know-it-all anchor mispronounce a word everyone with a pulse should know, leaving the tech guys busting a rib laughing.

So the humor was on the jagged edge and the pace was intense. There were a handful of times when I was writing copy for Anderson Cooper about forty seconds before it was to come out of his mouth. Lucky for me Anderson can edit on the fly, on air, while these never-before-seen words popped from my fingers onto the prompter.

One time with Anderson, I blasted in, with literally seconds to spare, something thoughtlessly inappropriate about kidnapping victim Elizabeth Smart, in some misguided attempt to be “edgy.” I watched Anderson process the words live and reject them, forcing him to vamp and instantaneously come up with something new and tasteful. Forced anchor vamping = massive fuckup for any copywriter. Crashing that hard, as we call it in news, left my hands sweating and my heart racing in one of the control rooms nicknamed the “Screamatorium.”

By 2003 (the peak “Hero” moment on my Career Suicide Note), it was in my head that my life needed radical change. The seed had been planted two years before on 9/11. I heard the first plane crash from my apartment, just like millions of other New Yorkers, while Steve watched it fly in overhead. We were by no means affected in a truly personal way by 9/11, that is, having a direct family member or friend murdered that day, as so many other friends actually did. (Yeah, you heard me, murdered. I’m one of those liberal pukes who felt zero ambivalence shouting out “Fuck, YEAH”—and then crying—when Bin Laden got it. Might have been a small fist pump, too. “About fucking time” is how this liberal reacted.)

But despite not having a family member or friend murdered, 9/11 had a cumulative effect on me: watching people cry in the streets holding “Missing” signs; seeing half my local firehouse wiped out; waking up to the smell of burning rubble for months after; being evacuated after a bomb threat with my boss screaming, “Everyone Get Out Now!”; writing endless stories about it at work; watching field producers come back from Ground Zero looking stricken; having guys in puffy hazmat suits walk around the office while my only protection from possible anthrax was an old, ugly Ann Taylor outfit. It added up, as I’m sure it did with countless other New Yorkers.

I vowed—quite uncharacteristically for a cynical sort like me—to take a chance on life, clean up my act, and have a baby. Steve said, “Sure, what the hell.” I think 9/11 affected him too, though in a different way. His foul-mouthed daddy lion voice spoke to him saying, “There’s no fucking way I’m raising my kid in this crime-ridden terror trap. Roar!” Not that we even had to debate the question. I knew I couldn’t be a mom, keep my sanity, and continue in the Screamatorium; and we couldn’t afford to stay in Manhattan on one salary. So off we went to the first of three suburbs over the next four years.

Within months of shvitzing in the Screamatorium, I found myself marooned in suburbia. Now, years later, with a happy son; a small house overrun with his brothers from different mothers; a select group of trash-talking friends; and Zoloft pills a-poppin’, I see it as the birthplace of my new life as a thirty-something mom. I have a new set of satisfactions and, of course, a bigger ass. But at first suburbia seemed like nothing more than the graveyard for my twenty-something dreams. (Sooo overdramatic, spoiled whiny white mommy! Trying to score the Pulitzer Prize for Overwriting? Good effort!)

I had gone from 80 miles an hour to zero, and I had vastly underestimated the crash this staggering deceleration might cause. My landscape now included Wal-Mart on one end of the class scale and Whole Foods on the other; and crossover between the two looked nonexistent. Nearly everyone was white (see Whole Foods), except nannies, cleaning ladies, and yard workers (see Wal-Mart), and all the dads and the working moms I never met vanished on the 6:04 a.m. train.

Suburbanites seemed to me to have one-track minds, and mighty clean ones, too. They were about one business, and one business alone: baby and then child-raising. On paper, I didn’t look so different from the other stay-at-home moms. They were mostly former professionals, too, some from Wall Street trading floors, which are easily as rough and tumble as any newsroom. But whatever edge these type-A women might have had now seemed gone, replaced by a version of hyper-vigilant parenting that was, to me, brutally boring and faintly absurd. They blathered on and on about how people without kids “just didn’t get it.” They seemed busy busy busy and, most important to me, appeared very short on laughs. One day I spotted some obscene playground graffiti and I was the only one even willing to acknowledge it, as in, “Look, that slide says VAGINA on it!” I wished I could share my glee with my potty-mouth ex-coworkers, since my new “coworker” moms had no interest. But they were back in the newsroom slamming a show together, while I was soon to establish myself as that weirdo mommy at Gymboree.

I knew very quickly that moving to the suburbs was a mistake when I realized that I missed my New York City doorman I’ll call Rob, who was such a cliché of the portly, klutzy, up-in-your-business doorman that no self-respecting comedy writer would ever dream him up. (And in fact, one of the world’s most successful comedy writers lived in my building as he, too, became a parent and eventually left for the suburbs: Adam McKay. How do I know this, since I’ve never met Adam McKay? Because Rob told me all about him, what a great guy he was, his nice wife and his adorable baby and his latest fantastic SNL sketch and. . . .)

Even at 11:30 p.m.—no, especially at 11:30 p.m.—when I was coming home to the East Village from work at CNN, exhausted, Rob would start in on an obscure Civil War fact, or deliver the results of the game he listened to on his handheld radio, or describe the latest outing he had with girlfriend “Gladys” (her real name, like Gladys, is straight out of an old-school sitcom, just like Rob himself). Rob could and would talk about anything, and he would still be talking as the elevator doors closed. Years later, he’s surely still talking. If Rob had suddenly found himself in my suburb, an army of concerned mommies would have dragged his fifty-year-old ass in for a special-ed evaluation, because Rob might well have had Asperger’s.

So it was while pushing a baby stroller through a suburban mall (my new “town square”) that I started missing not just my urban friends and job, but especially Rob, my go-to conversation machine, and all the other random faces I would bump into, sometimes literally, going about my city life. I had gone from living vertically with dozens of couples or single people in the same building (using the same elevators, clogging the same trash room), to living horizontally, families cut off from other families in their own cocoons: self-imposed segregation in a most concrete way. Feeling so cut off surely magnified a nasty case of postpartum depression and the crushing loneliness that came with it. That’s when I turned into, well, the stay-at-home-mommy version of Rob.

I began talking to everyone, anywhere, anytime, all the time. Were people’s facial cues telling me to back the fuck off, you crazy mommy? I didn’t care. I followed a circuit of library story times with the devotion of a Dead Head (story time for tiny infants, mind you, who still don’t know the difference between you and their own hand). I ate at the same diner every morning, ordering the same two-dollar egg sandwich until the waitress busting her ass recognized me. Yeah, she recognized me alright, as the spoiled mommy bitch who didn’t have to work and wouldn’t stop smiling at her, attempting pleasantries. I became an avid student of nanny culture and racially profiled them to find the most talkative ones. My inappropriate, sweeping generalization is that Caribbean nannies seemed the chattiest, and often cattiest, and therefore most desirable to me. I swear one favorite nanny showed such contempt for the parents of the boy-prince she was caring for that I thought her eyes were going to roll out and drop on to the park bench.

I attended a ragtag sing-along at a bookstore that usually attracted just a few passersby and me, the sad-sack regular with her quarrelsome baby. The sing-along leader was Jean, a sixty-something sweetheart, who was so scattershot I thought she was either drunk or mis-medicated. She would sort of punt on her kiddie playlist after just a few highly awkward songs and one day even said, “Linda, you take over.” She seemed more unhinged than me, and that’s saying a lot. (Jean didn’t have a car, I learned, when I saw her blowing around in the rain waiting for a bus on a hugely busy, dispiriting commercial thoroughfare. I picked her up. A suburbanite without a car: the ultimate outcast.)

And, as I mentioned, I joined a Gymboree class. That’s where I met Bridget, Luv, as I called her in my head. Bridget, Luv, of course, was Irish; an older woman and a local legend among the baby-raising set for her savant-like knowledge of newborns. In my haze of postpartum depression, I had five of the worst seconds of my life in her class, when I actually forgot my beloved son’s name, Frank. After class, I was so distraught I didn’t want to leave Gymboree or Bridget, Luv, who said to me, “You have the bad baby blues, luv. I seen it a-tousand times.”

All my pent-up loneliness plus my suppressed impropriety had to go somewhere, and that somewhere was online. Google my name and in a few clickety-clicks you’ll find a sorry list of intimate grotesqueries I cataloged about myself with abandon when the meds finally kicked in, I got my writing act together, and I started submitting to the Boston Globe and the Huffington Post. I was determined to entertain myself, even if it meant looking like a self-obsessed exhibitionist begging for laughs.

Much of the indignity happened on Facebook, which is just vastly more diverse than my real life in suburbia. (Please friend me, Linda Erin Keenan, on Facebook if you’re so inclined. The crazier you are, the better. I genuinely love it.) Like other lonely souls out there, I fell into that vortex of making Facebook my real, not-real community. How could snow-white suburbia compete with this picture? I realized it could be my own massively Awkward Facebook Family Photo: the homeless artist, the Pakistani mariner, the military fetishist, the Renaissance faire–loving transsexual lesbian massage therapist, the evangelical Republicans, my fashionista Mormon, the very sweet Sikh, the homeschooling pagan, two home-birthing doulas, the Texas BBQ restaurateur who promotes “burnt end sandwiches” right next to the hard-core vegan telling us that, say, my beloved Hot Pockets are killing me. All there and much much more in my wonderful Facebook nuthouse. Oh, and Buddy the Elf. He’s there, too. He works for Santa. Says he’s a real bastard.

In private, I pushed my boundaries further and began writing fake news satire, because eventually I went from bored to fascinated with the habits and fixations of upper-middle-class suburban life and parenting culture—like the bubble-wrapping of the affluent child—and what that says about America. Why do so many of the world’s luckiest people seem so damn anxious?

I’m fascinated by the way some women mercilessly judge other women’s choices, and what motivates the harshest proponents of the “pure” and “natural,” especially in terms of breast-feeding. I see a lot of gory, competitive masochism in this area, like, say, “My nipples bled more than your nipples.” “No, MY nipples bled more AND I got mastitis and then septic-shock!” Well, at the risk of having frozen bags of breast milk pelted at my door, I really don’t get why people are so passionately interested in how I feed my child or how I use or view my own breasts. As I recall, they are my breasts, and that baby is my baby, and it’s actually quite an intimate act to press on others with such vigor. I also don’t understand the many women and men who vocally trash those who breast-feed their kids publicly, or for years and years. None of your business.)

I do have friends who believe strongly in breast-feeding, but they are lovely, advocate for all women, including the poor here and around the world, where breast-feeding can be a life-and-death choice for a baby if water is dirty. These activists are not toxically judgmental like, say, the “Breast-feeding Nazi Really a Nazi” I write about in the book. But vicious invective from others can be found all over the Internet. And passive-aggressive, thoughtless comments on breast-feeding, C-sections, epidurals, circumcision, staying at home versus working, and organic-food eating can have ugly impacts on fragile moms who choose to do things differently, or who might not even have a choice. It sure did on me, and on innumerable other friends.

Sadly, I think some of these movements inadvertently add to the yawning divide between rich and poor, or educated versus less educated. Not because the underlying goals of breast-feeding or eating organic food are unworthy, but because we are simply not set up in this country for subsidizing healthy food or fully supporting working mothers who breast-feed, poor or otherwise. Really, how does a woman working at low pay afford a souped-up Medela breast pump? How many women have jobs that will allow time to pump? Breast-feeding is only free if you don’t put value on a woman’s time.

Michelle Obama can exercise her ass off all over the country (and God love her for it), but until we end, say, distorting food industry subsidies, the poor and middle class have every incentive imaginable to eat cheap crap, and many of the “well meaning” make the less fortunate feel guilty about it. Eating like a locovore is all good and great, but it’s often expensive, time-consuming, and simply impossible for people of average means.

So the poor and middle class seem to be getting less and less healthy, while affluent suburbia (and “urbia,” too, for that matter) plies itself with every high-priced age-defying product, time-consuming betterment program or Whole Foods supplement, and basically jogs itself straight into its hale and hearty future. These days, Fat = Poor = Shame, as seen in “Woman Shops at Wal-Mart to Feel ‘Pretty, Thin,’” among other pieces. Class, race, and religious collisions in mostly monochrome suburbia really interest me.

In a broader way, I also began thinking about America’s diminished place in the world and how it might translate to the everyday business of raising a family; this whole idea of “living the dream” and maintaining a kind of phantom affluence in the so-called Great Recession.

For instance, why did Amy Chua’s tough-parenting Tiger Mom book strike such a chord? Do we fear she may be right, that we Americans are coddling our kids into mediocrity? I wrote “Indian Child Taunted as ‘New Jew’ at Middle School” several years ago and thought Chua’s “shaming” as an overdemanding mommy-shrew was quite similar to what happens to my overperforming immigrant Chaudry family.

Amidst this anxiety, I feel like in wealthy suburbia we not only Bubble-Wrap our kids from the broader world, but also ourselves, even as wars are being fought in our name by our less fortunate, rural, urban, and not comfortably suburban countrymen.

Meanwhile, I have seen the insistent creep of anti-Muslim, anti-“other,” anti-teacher, and anti-union resentment that has been percolating since 9/11, but really seemed to explode as the economy collapsed and when President Obama was elected.

I was actually asked if I would prefer another doctor because the one I selected, a Sikh, wore a turban. You’ll see that story, a Sikh gyno’s desperate bid to keep patients, in an op-ed titled “I Am Certified Not Muslim . . . And I Love Your Feminine Area!” I labeled these op-eds Shout Outs.

On a more personal level, I’m interested in the way we transmit our biases and neuroses (especially my own), like female body self-hatred, to our kids. If you see pieces attacking women, just know that, very often, I am attacking myself. Not to be hopelessly cliché, but I love how a child’s unspoiled view of the world challenges our own jaded beliefs and often leaves us flummoxed. If I used to call bullshit on the Taliban, my own son now calls bullshit on me; and if you’re a parent, you surely get what I’m talking about. And I see the way we rewrite our sometimes sketchy pasts once we get to suburbia, because You’re a parent now, and that old life is over—especially the dirty, sexy parts. I am fascinated and frankly sad that Suburgatory seems to be where sex goes to die, or at least gets suppressed. Well, it comes pouring out in this book, so get your raincoat!

I have also included history’s worst advice columnist—Dr. Drama—who gets earnest questions and wants nothing more than to stir the shit out of your already messed-up life. This was inspired by the often riotous and toxic comment sections of real website advice columns, where anonymity lets people project and splay their crazy any which way.

And it should go without saying that anything labeled Paid Advertising Content is not a real ad. Believe me, I wish those were real. That would mean more money for me and my amazing agent, editors, and publisher. Also, as I mentioned above, I have lived in three suburbs in two states and have gotten ideas and themes from friends who live in a dozen more, mostly white, mostly affluent suburbs.

Suburgatory is not the town where I live now. I wouldn’t stay here if it was, because some of the fictitious people you’re about to meet are truly awful—and, hopefully, awfully hilarious. Any of the real people mentioned are, of course, used solely for parody purposes; Cynthia Nixon, a great actress and public school advocate, did not suddenly move to suburbia with her partner. Blogger Perez Hilton did not take a job as suburbia’s zaniest new “Manny.” New York Times columnist Tom Friedman did not threaten an all-powerful high-school guidance counselor with a nasty column. And surely, Wolf Blitzer did not really report “Live from the Lactation Room,” though I’d give my left nut to see that actually happen for real. It’s all satire and I’d hope Wolf, an anchor I long admired from afar at CNN, would get the joke.

So do I think of myself as a Big Fat Zero, like the Social Security Administration thinks I am, a no-paycheck parasite? No, because I neglected to mention that the Big Fat Zero did include a Plus One, and that would be the love of my life, my son, Frank Keenan Mendes. I only hope he never reads this book and realizes how sick and twisted his “Best Mom Ever” really is. Maybe after my funeral! And so I begin with a piece that’s in large part true (though not the baptism part) about the near-year I spent as a secret atheist surrounded by simply wonderful Baptist believers. It is no exaggeration to say that these ladies helped save me from the abyss of postpartum depression. But sadly for them, they did not save me from hell.