Chapter 3

In a short time Mr. Doty was very popular with the animals on the Bean farm. The stories of his adventures were endless, and he seemed to like nothing better than to tell them to anybody who would listen. He spent most of his time sitting on the back porch, surrounded by a crowd of pop-eyed animals, gasping at the tale of some hair-raising exploit.

Charles was the only one that held back. His crowing, which was a signal for everybody on the farm to get up in the morning, had no effect on Mr. Doty, who simply pulled the covers over his head and went on sleeping. Sometimes it was nearly eleven before he came downstairs. This was a challenge to Charles. On the third morning he flew right up on the windowsill of the spare room and crowed as loud as he could. Mr. Doty got up all right. He got up and threw a shoe at Charles, knocked him off the sill, and badly bent one of his longest tailfeathers. Charles was pretty mad.

One hot afternoon, Jason Brewer walked out from Centerboro to see Freddy. The pig was up by the back porch, listening with some of the other animals to Mr. Doty’s account of how he had once fought an Indian chief with bowie knives for the leadership of a tribe of Apaches. Mr. Doty broke off as the boy approached.

“Well, well,” he said, “visitors!”

“Hello, Jason,” said Freddy. “Come over and meet Mr. Doty.” And when the two had shaken hands: “Did you come up to go swimming in the duck pond?”

“I thought maybe we could,” said Jason. “But if you’re too busy—”

“Swimmer, are you?” Mr. Doty said. “Well, well, I used to do a little in that line, ’deed I did. Was on the Olympic team in—twenty-one, was it? I forget the year. Did I ever tell you, Freddy, how I once swam Lake Ontario?”

“Why don’t you go up with us, Mr. Doty?” Freddy asked, and Jason said: “Oh, would you? You could teach us some things.”

“Well, well, I could at that,” said Mr. Doty. “But some other time. A bathing suit I haven’t got.”

Mrs. Bean, who was working near the kitchen window, put her head out. “I’ve got just the thing, Aaron; you wait.” She disappeared and came out presently with a brown paper package. “Mr. Bean bought this,” she said as she unwrapped it, “when we went to Niagara Falls on our wedding trip. He had some idea that he could go swimming there, I guess. But when he saw the falls he changed his mind.” She drew out the suit and handed it to her brother.

Mr. Doty held it up and the animals giggled, for it was the kind that used to be worn fifty years ago—red and white striped, with sleeves that came below the elbow, and legs that flapped loosely around the shins.

“Well, well,” said Mr. Doty, “so old William wore this, did he? Quite a figure he must have cut. Too small for me.”

“Nonsense!” said Mrs. Bean. “It’ll fit fine. You go along and have your swim.”

“I don’t believe I’d better go today,” said Mr. Doty. “My shoulder’s been kind of bothering me—it’s the old wound I got in the Spanish-American War—when we charged up San Juan Hill—”

“You must have charged up it in your baby carriage then,” said Mrs. Bean sharply, “for you were only two when that war started.”

Mr. Doty looked puzzled. “Well, well, is that so? I guess you’re right, Martha. I been in so many wars I get ’em sort of mixed up. Well, it don’t signify. The wound’s there, and I ought to favor it. Wouldn’t do to go in the cold water.”

Just then Mr. Bean came around the corner of the house. “Hey, Aaron,” he said, “want to give me a hand getting that old maple by the barn down? If we don’t, the next good blow’ll topple it right over on the roof.”

Mr. Doty hesitated for a long minute, looking at the crosscut saw that Mr. Bean was carrying. Then he said: “Why, William, I just this minute promised Freddy I’d go up and teach him some fancy diving. How about tomorrow?”

Mr. Bean just shrugged his shoulders and went off towards the barn.

“You go help him if you want to,” said Freddy.

“No, no,” said Mr. Doty. “Not when I’ve given my word to you. No, sir; keep your word, no matter what it costs you—that’s my motto.”

“But you hadn’t given your word yet,” said Jason.

“Well, well, well; an argument, hey?” said Mr. Doty. “Why of course I hadn’t said I’d go, right out. But I’d said so in my mind. I’d made up my mind, and that’s the same as a promise, isn’t it?”

Freddy would have liked to argue the point a little longer, but Mr. Doty got up, and with the striped bathing suit slung over his shoulder, walked across the barnyard. “Come along,” he said; and when they started after him: “Did I ever teach you the Ogallala warwhoop, Freddy? It’s a pretty ferocious sound. Makes your blood run cold when you’re camping alone on the prairie and you hear—this!” And he took a deep breath and then let out a long high screech. “Come on—try it! That’s the stuff, Freddy. Give it all you’ve got, Mrs. Wiggins—we’ll make a warrior out of you yet.” And then as they all began imitating the screech he had given, Mr. Doty waved the bathing suit around his head and started running. “Come on!” he shouted. “We’re a band of Ogallala Sioux, and we’re going up to set fire to the duck pond and scalp the ducks!” And the boy and the animals pounded after him, yelling at the top of their lungs.

Alice and Emma, the two ducks, were sitting on the pond, entertaining a caller. The pond was really their parlor and dining room combined; the parlor was upstairs—that is, it was the surface of the pond; and the dining room was downstairs—the rich layer of mud on the pond’s bottom, where they hunted for things to eat. They were proud of their parlor, because like all ducks they looked their best on the water, where they swam easily and gracefully. On land, their movements were neither easy nor graceful; they waddled; and even some of the best-mannered animals on the farm could not help snickering when they saw the two out for a walk.

But there were very few callers whom the ducks could entertain in their parlor. The animals usually sat on the bank, and if the ducks invited them in they always wanted to swim and splash about, which is not parlor manners and makes polite conversation impossible. But today’s caller was quite at home in the water. He was Theodore, a frog from the pool up in the woods, and he floated between Alice and Emma, with just his nose and his goggle eyes sticking out, and exchanged small talk about the weather and the local gossip.

A third duck, Uncle Wesley, had not joined his nieces in the parlor. He was sitting under the shade of a burdock leaf on the bank, muttering grumpily to himself. “I have never associated with frogs,” he grumbled, “and I don’t intend to begin now. Horrid clammy bug-eyed creatures!”

Alice and Emma were very much embarrassed by Uncle Wesley’s conduct. They tried to keep between him and Theodore, and they both chattered at a great rate so that the frog wouldn’t hear their uncle’s remarks. Of course Theodore did hear, but he was too polite to show it.

Emma was just remarking that she thought we were going to have an early fall, when Alice said: “Sister, what’s that?”

It was of course the yelling of the Ogallala Indians led by Mr. Doty, and as it approached I guess it was as frightening to ducks as to any camper on the lone prairie. Alice and Emma, quacking excitedly, spread their wings and skittered across the water for the shelter of the reeds at one end of the pond; and Theodore, after listening for a moment, dove down into the mud in the ducks’ dining room. Uncle Wesley, peering out from under his burdock leaf, saw what he thought was an armed mob charging up the slope, brandishing a red flag. They were so close that he knew it was safer to stay where he was. He crouched down closer to the ground and put his head under his wing and trembled.

The Indians reached the pond and threw themselves down in the grass to get their breath. Then Mr. Doty went off with Jason to put on their trunks and bathing suit. The ducks heard laughter, and familiar voices, and came gliding out from among the reeds, feeling rather foolish, and Theodore, coming up presently for air, also heard them and hopped up on the bank. But Uncle Wesley, with his head under his wing, didn’t hear anything. He stayed where he was.

“Well,” said Freddy, “what are we waiting for?” And he walked out to the end of the springboard that Mr. Bean had put up for the animals, and jumped in. The boy and the other animals followed, until at last everybody was in but Mr. Doty.

“Come on,” said Freddy; “aren’t you going to show us some dives?”

Mr. Doty sat down on the bank and put his left big toe in the water, then drew it back with a shiver. “Fancy diving I never liked much,” he remarked. “Always seems too much like showing off. Anyway, my specialty was swimming races.”

“What stroke do you use?” Jason asked. “Show us.”

Mr. Doty shook his head. “This pool is hardly big enough for a demonstration. Terrific speed I work up—two strokes, and my head would hit the other bank.”

“You couldn’t work up much speed in two strokes,” said Jason.

“Ha, you don’t know me! No, you go ahead and enjoy yourselves. I’ll get in later.”

Alice and Emma were keeping off at a safe distance from the others. “I suppose that bathing suit of Mr. Doty’s is the latest thing,” Alice said, “but I must say it isn’t very becoming.”

“It’s in very bad taste, if you ask me,” said Emma. “So conspicuous with those bright stripes.”

Theodore’s head popped up between them. “What’ll you bet I can’t get old Dud-dud, I mean Doty into the water?” he said. Theodore always stammered a good deal, though he really didn’t have to. He said he’d started doing it because when anybody asked him a question it gave him a little extra time to think up a good answer. And now he did it without thinking.

“We do not approve of betting,” said Alice primly.

“Neither do I,” said the frog, “unless I’m sure I can win.” He winked one bulging eye at them and disappeared.

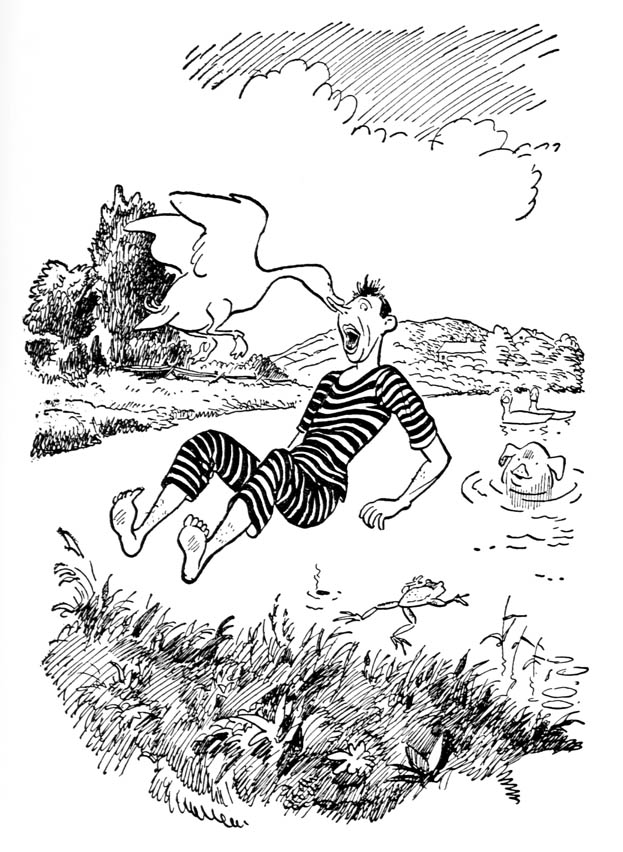

A minute later he crawled out on the bank and in two long jumps he was around behind Mr. Doty, who had lighted a cigar and was standing at the edge of the water, shouting advice and encouragement to Freddy. Then he gathered himself together and with one long spring landed square and clammy on the back of the man’s neck.

Mr. Doty threw up his arms, his cigar flew out of his mouth, and with a warwhoop that would have scared any number of Ogallala Indians, he lost his balance and plunged after the cigar. Little bits of the uncompleted warwhoop came up in a string of bubbles.

Fortunately the water was not deep on that side. Mr. Doty reappeared almost immediately. As soon as he stopped sputtering, Mrs. Wiggins said: “That was a real pretty dive, Mr. Doty. And quick! My land, when you dropped your cigar, it had hardly left your mouth when you were right after it.”

“Don’t believe in wasting things,” he said, and started to climb up on the bank.

“Aren’t you going to stay in and show us some stunts?” Bill asked.

“Well, well, I’d like to. But the water’s pretty cold today and the trouble is, I’m subject to cramps.”

All this time Uncle Wesley had been cowering under his burdock leaf with his head tucked tightly under his wing, and he hadn’t heard much of what went on. But he did hear Mr. Doty’s yell. He took his head out, and there in front of him was a piratical looking stranger climbing up out of the water and apparently coming straight for him. Uncle Wesley wasn’t very brave, but even a cornered duck will fight, and he felt that he was cornered. He flew up and grabbed Mr. Doty’s nose with his strong yellow bill and twisted.

He flew up and grabbed Mr. Doty’s nose.

Again Mr. Doty gave the warwhoop and fell into the water—backwards this time. And again the end of the yell came up in bubbles, while Uncle Wesley fluttered free and, half flying and half swimming, made for the reeds.

Mrs. Wiggins was all admiration. “You did it again!” she exclaimed. “And backwards this time! That was wonderful!”

But Mr. Doty was mad. He scrambled ashore and picked up a stone and threw it at Uncle Wesley. His aim was poor and he barely missed Emma.

“Hey, take it easy,” said Freddy. “Wes didn’t mean any harm. You scared him.”

“Is that so!” Mr. Doty gave Freddy a mean look. “Well, I’ll wring his neck if I ever get hold of him.” And he picked up another stone and threw it. This time it didn’t come within yards of the ducks.

Freddy looked at Mrs. Wiggins, and then at Bill and Robert and Georgie, and they all got up and went over and stood in a ring around Mr. Doty. Jason came along too. They didn’t look threatening or anything—they just stood and looked at him. And Mr. Doty, who was stooping for another stone, straightened up and gave an uneasy laugh. “Well, well, well,” he said; “mad at me, are you? Why I wouldn’t hurt him. Ducks I wouldn’t attack. Lions and rhinoceroses, yes—done it many times. But ducks, no. Just wanted to scare him a little. I didn’t try to hit him; you saw yourselves how the stones didn’t come anywhere near him.”

“Maybe you aren’t a very good shot,” said Georgie.

“Well, well, so that’s what you think, eh? Let me tell you, I hit what I aim at. Why, when I was pitching for the Cards there’s game after game I’ve struck out ten, fifteen, twenty men.”

“Yeah?” said Georgie. “Let’s see you hit that fence post over there.”

Mr. Doty swung his right arm around a couple of times. “No,” he said. “I’d better not. It’s a long time since I pitched a game and my ligaments ain’t real tight. Might stretch one, and then I’d be laid up good. Guess I better get this wet bathing suit off,” and he went back to where he had left his clothes.

Pretty soon they started home. Freddy looked at Jason’s sweater. “What have you done with the C.H.S. you used to have on that sweater?” he asked.

“I ripped it off,” said the boy. “I guess I just couldn’t take the kidding. You know what everybody says it means: Can’t Hope to Score; Creep, Hobble and Stumble. They make up a new one every day. I don’t think we’ll have any team this year; I don’t think anybody’ll come out for it.”

“Well,” said Freddy, “I don’t think you ought to be ashamed of being on a team just because it loses. I saw your second game with Tushville last year. You put up a good fight, but they were just too heavy.”

“Quite a football player myself I used to be,” put in Mr. Doty. “Never forget the game we played against Notre Dame. Made three of the four touchdowns myself. The last one, I wasn’t only carrying the ball, I was carrying their big left guard, too—Winooski, his name was. He’d tried to tackle me, ye see, and I couldn’t shake him off, so I just picked him up and tucked him under my other arm and carried him over the line.”

Freddy had become convinced by this time that Mr. Doty’s stories of his exploits were all lies. They were rather harmless lies, because Mr. Doty evidently didn’t expect anybody to believe them. Nobody, for instance, could run with a two hundred pound football player under one arm. Freddy thought Mr. Doty just told them for fun. He said so to Mrs. Wiggins when they got back home.

Mrs. Wiggins didn’t agree. “He wouldn’t tell those stories to the Beans,” she said. “No, sir, he thinks animals are stupid. Dumb animals—that’s what most people call us. He thinks we’ll believe anything.”

“I sort of like him, though,” said Freddy.

“Land sakes,” said the cow, “I don’t object to a liar, as such. He’s a lot of fun, too. Only I wouldn’t trust him much. He’s using lies every day, and if he got mad at you, he’d pick up the handiest thing to get even with. And what has he always got handy?—a good fat lie.”

When Jason started home, Freddy walked down to the gate with him. “I think you ought to sew those letters back on your sweater,” said the pig. “You played the game hard; you’ve nothing to be ashamed of.”

“I’m not ashamed really,” said Jason. “The reason Tushville has piled up such big scores is that they’ve got a lot of ringers on their team. There’s four of those boys in the last game that must be twenty years old; I bet they don’t even go to school.”

“Well, can’t you do anything about it?”

“I don’t see how. We tried to get Mr. Gridley, our principal, to do something, but he doesn’t like football and he wouldn’t. He thinks we ought not to have a team anyway. Can’t you think of something, Freddy?”

“Why, sure,” said Freddy. “Sure. I’ve got several ideas already. H’m, let me see … Give me a day or two to mull it over, Jason. So long now.”

Freddy’s conscience bothered him as he walked back to the pig pen. He’d said that he had several ideas. That was true enough. But they weren’t very good ideas. “I suppose it’s an idea to put a lot of lions and tigers into football suits and have them play on the Centerboro team. And it’s an idea to shoot all the Tushville team. But they’re neither of them really ideas because they couldn’t be used. I guess I’ll have to make good on this. I guess I’ll really have to do a little mulling, whatever that is. I don’t want to get like Mr. Doty.”