Chapter 10

Since their return from the west, Mr. and Mrs. Webb had been giving a series of lectures on their experiences. Their voices were of course rather small for lecturing; they would only carry a distance of about two inches; but Freddy had twisted a big sheet of paper into a cone to make a sort of megaphone for them, and when they spoke into the small end, it magnified enough so that a dozen or so animals grouped about the large end could hear clearly. Mrs. Webb’s lectures were Hollywood From a Hat Brim, and Screen Celebrities I Have Met She was a talented mimic, and could entertain an audience for hours with her imitations of various movie stars. Her imitation of Betty Grable was extraordinarily lifelike.

Mr. Webb’s talks were more serious: there was one on How I Broke Into the Movies, With Practical Hints For Beginners. Another, and a very thrilling one, dealt with perhaps their most dangerous experience, when they had been sucked up by a vacuum cleaner, whirled through into the dust bag, and had barely escaped with their lives. He also sang a few western songs in the manner of Gene Autry, and although he had neither a horse nor a guitar, everybody felt that he brought the very spirit of the open range to the platform.

The lectures were so successful that when Mr. Muszkiski, who ran the Centerboro movie theatre, read an account of them in the Bean Home News, he came out to the farm and engaged the Webbs at quite a large salary to come down once a week, on the evening when there was no show, to give them at his theatre. There was a microphone on the stage, and when it was turned up high their voices could be heard even in the last row of seats. Of course from the orchestra, their gestures couldn’t be seen, and even the Webbs themselves were only tiny black specks, but at Mr. Muszkiski’s suggestion, the audience all brought opera glasses and binoculars and telescopes, and when Mrs. Webb did her imitations, they stamped and cheered till the windows shook. Even the Beans came down one evening and made as much noise as anybody.

But of course the Beans were pretty unhappy, for the date was approaching when Mr. Weezer had to lend them the money for Mr. Doty. The animals noticed that Mrs. Bean no longer sang while she was doing the housework, and Mr. Bean no longer smoked his pipe, because he was saving money by not buying tobacco. It made them feel sad to see him without smoke puffing out of his mouth and seeping out of his whiskers; it was like looking at an abandoned factory chimney, and they began to turn against Mr. Doty. Fewer and fewer of them came to listen to his stories, and when he came out in the barnyard they turned their backs and walked away. When he noticed this, the mean streak in Mr. Doty came out. If a dog walked away without answering his whistle, he would call it names, and even throw stones at it. Perhaps he thought they were afraid of him. But he was in a good deal more danger than he realized.

He did realize it a little when the animals began to play tricks on him. A dog would creep up behind him and bark suddenly, or if he held out his hand with a lump of sugar for Hank, the horse would put his head down and smell of it, and then bring his head up quickly to catch Mr. Doty a crack under the chin. Or a cow would switch her tail and whack him on the nose. Uncle Solomon, the screech owl, spent one whole night flying into Mr. Doty’s window every half hour and giving his crazy laugh from the head of the bed. And always, wherever Mr. Doty went, even in his bed at night, there were ominous rustlings and whisperings and gigglings.

He complained to the Beans about it, and finally Mrs. Bean spoke to Freddy. “You animals ought to like me well enough to be nice to my brother,” she said.

“We don’t think he’s your brother, ma’am,” said Freddy.

“You must let me be the judge of that,” she said severely. Then her face softened. “You know, Freddy, I have thought it all out. It could be that he isn’t Aaron. But even if there was doubt in my mind—which there isn’t—I’d have to give him his money. I couldn’t run the risk of cheating my own brother out of his inheritance.”

One afternoon—it was one of the days when Weedly had substituted for him in school—Freddy had just started football practice, when he saw Mr. Gridley beckoning to him from the sidelines. He ran over and said: “Yes, sir?”

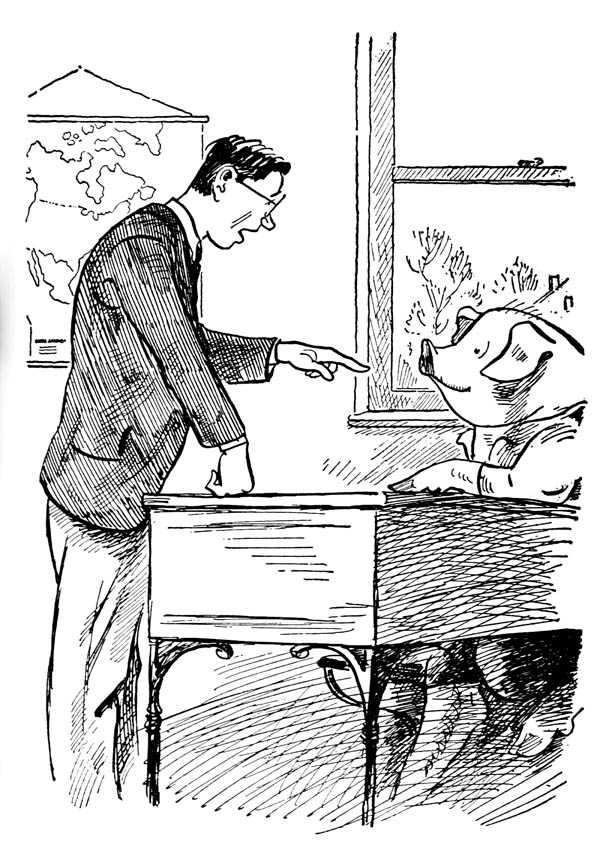

“What are you doing here?” said Mr. Gridley accusingly.

“Why, I come out here every day after school,” said Freddy.

“So I see,” said the principal. “You come out even when you’re supposed to be staying after school?”

Freddy guessed at once what had happened. For some reason or other Miss Calomel had told Weedly to stay after school. He was probably there now. “Golly!” he thought. “I’m in a spot! If he finds out that Weedly is taking my place—”

“You come back with me now,” said Mr. Gridley.

There wasn’t anything else to do. They walked back to the school together. At the door of Miss Calomel’s room, Mr. Gridley started to go in, but the second his back was turned Freddy, instead of following, sneaked off quickly down the corridor. He went out and waited up the street that Weedly would have to pass through on the way home.

In about half an hour Weedly came along. “Hi, Freddy,” he said; “say what’s biting Mr. Gridley? I had to stay after school, and a little while ago he came tearing into the room, but when he saw me he said: ‘How’d you get here?’ Miss Calomel started to tell him I’d been there all the time, but he just turned around quick and stuck his head out the door and looked up and down the hall, and then he came back and said: ‘Didn’t you just come in here with me?’

When he saw me he said, “How’d you get here?”

“Miss Calomel said: ‘How could he?’ and I said: ‘No, sir, I’ve been right here,’ and then he looked kind of wild and dropped down into a seat and began mopping his forehead. Miss Calomel just stared as if she thought he’d gone crazy, but he didn’t say anything; and pretty soon he got up and went back to his office.”

Freddy told his cousin what had happened. “I guess Mr. Gridley must believe in ghosts,” he said, “or he wouldn’t have been so scared. If he does, maybe we’ll get away with it. But if he gets to thinking and finds out there are two of us—”

“Yeah,” said Weedly. “Two Freddys would be pretty hard to take, specially if each one of ’em is only half educated.”

“Well, if you have to stay after school again,” said Freddy, “you must tell Jason so he can let me know. He’s the only one I’ve told about us. I’ll be going to school tomorrow; if Mr. Gridley doesn’t say anything then, we’ll be safe.”

All pigs look about the same to people, although they look different to pigs. And evidently it never occurred to Mr. Gridley that there was more than one Freddy in school. He said nothing more about the occurrence, but he eyed Freddy almost fearfully when they met in the halls. Miss Calomel had her suspicions, because Freddy acted different on different days, and he seemed to have a terrible memory. Once she said: “Freddy, I think you’re only about half here.” Which was true; she was really only teaching half a pig. But she was a great football fan and wanted the team to win, so she kept her suspicions to herself.

The first game of the season was with Plutarch Mills, on October third, a week before Mr. Bean was to get the five thousand dollars from the bank. The schools were evenly matched; of two games the year before, Centerboro had won one, 6-0, and the other was a tie. The team was driven over to Plutarch Mills in the school bus, and half Centerboro piled into cars and followed along, for everybody knew by this time that Freddy was on the team, and even those who weren’t much interested in sport were curious to see a pig play football. The Bean animals, of course, attended in a body, and Mr. Doty drove Mr. and Mrs. Bean over in his car.

Mr. Finnerty had wanted to save Freddy for the first Tushville game, the following week. But he realized that if the Centerboro people didn’t see the pig play, they would be badly disappointed. So he put Freddy in at once.

The Plutarch Mills boys had heard that a pig was playing on the Centerboro team, and while the players were warming up they watched Freddy curiously. They decided that he didn’t look very dangerous, and they laughed and kidded him a lot. Freddy didn’t mind but Jason got mad when Charlie Jackson, the Plutarch captain, pointed to the C.H.S. on his sweater and said: “What does that stand for—Centerboro Hog School?”

“Sure,” said Jason. “And P.M.H.S. stands for Pig Makes Huge Score. Ask me about it after the game.”

As a matter of fact nobody piled up a huge score. Centerboro kicked off. The wind was against them and the kick was short. Charlie Jackson got the ball and started back, well protected behind strong interference, and the Plutarch Mills cheering section went wild, for Charlie was their fastest back.

Then Freddy drove in on them. Running on all fours, the pig was so heavy and so close to the ground that it was almost impossible to knock him over. Instead, one by one, the Plutarch blockers went head over heels. Then he made for Charlie. The boy tried to dodge, but Freddy was too quick for him. Of course he couldn’t tackle, for his forelegs were too short to hold, so he just ploughed through Charlie and cut his legs from under him. The ball was jarred out of Charlie’s grip and dribbled off to one side, where Henry James fell on it.

With the ball in Centerboro’s hands on the Plutarch 40-yard line, Irving Hill, the quarterback, signalled for Jason to take the ball straight through the line, between left tackle and guard. He counted on Freddy to open a hole that Jason could go through. To the spectators, it looked as if the line had exploded. The opponents’ right tackle and guard flew into the air, Jason followed Irving through the opening, and saw Freddy ahead of him, knocking off the backs, who were converging to tackle him. Jason made twenty yards before he was pulled down.

During the whole of the first quarter Irving kept calling for line drives, and each time Freddy broke through, and scampering about the field on all fours, bowled over the opposing tacklers, while Jason followed with the ball. When the quarter was over the score was Centerboro 23—Plutarch Mills o, and the Bean animals and the Centerboro people who had come over to see the game had cheered so much that hardly one of them could talk above a whisper.

But Mr. Finnerty was not too well pleased. “You can’t have Freddy play your whole game for you,” he said. “For one thing, you’ll wear him out before the game is half over, and for another, it’s bad football to rely on just one man, or one type of play. You haven’t punted, you haven’t thrown a single pass, you’ve just plugged at that one spot in the line. I’m taking Freddy out. Now go in and use some of those plays you’ve been working on all fall.”

After this the game was more interesting to watch. Plutarch Mills were becoming pretty demoralized, but with Freddy out they tightened up and pulled out two touchdowns in the second quarter. The final score was 30—14.

After the game the coaches and the captains got together. “We ought to protest your playing a pig against us,” said the Plutarch coach. “But we’ve decided not to, and I’ll tell you why. We’re a weaker team than Tushville, and if we don’t protest it will make them look pretty small if they do. So probably they won’t. And what we want to see is that gang of Tushville bruisers get licked. We’re all coming over to see that game.”

“Well,” said Mr. Finnerty, “you’re good sports. But such a protest couldn’t be made to stick anyway. Freddy’s a regular pupil of the school. Tushville can protest until they swell up and bust, but it won’t do them any good.”