Chapter 13

When Mr. Garble had learned from Mr. Doty that Freddy suspected them of plotting to get Mr. Bean’s money, he was pretty nervous. And when Freddy called, pretending to be the real Aaron Doty, he had got good and scared. He had a lot of respect for Freddy’s detective ability, and he saw trouble ahead. When Freddy took the five thousand dollars and disappeared he saw his chance. He joined the sheriff’s posse.

The sheriff knew pretty well what Freddy was up to, but it was his duty to catch him if he could. He and his men had combed the country around the Bean farm pretty thoroughly, but they had not yet gone into the Big Woods. Mr. Garble wanted to search them on Sunday, but the sheriff had said No, Sunday was a day of rest. “I don’t ever chase criminals on Sunday,” he said. “As a matter of fact, I don’t see why a criminal shouldn’t get Sunday off as much as anybody else.”

So Mr. Garble went out alone. He came down from the north through the Big Woods, and searched the Grimby house, and having found no clues, kept on and cut across the back road just about where Freddy had. It was then, as he was working down through the Bean woods, that he heard voices. He crept forward, and there at the pool he saw Freddy.

Of course Freddy didn’t know, when Mr. Garble’s pistol was pointed at his head, that it wasn’t loaded. So he just stood very still. There was a plop as Theodore dove into the pool. But the owl didn’t stir.

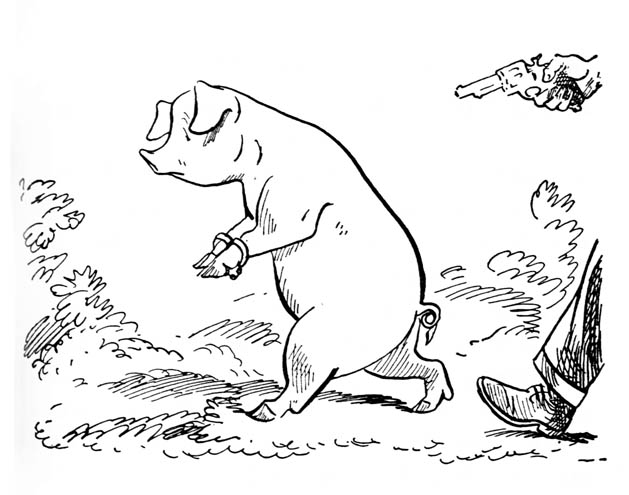

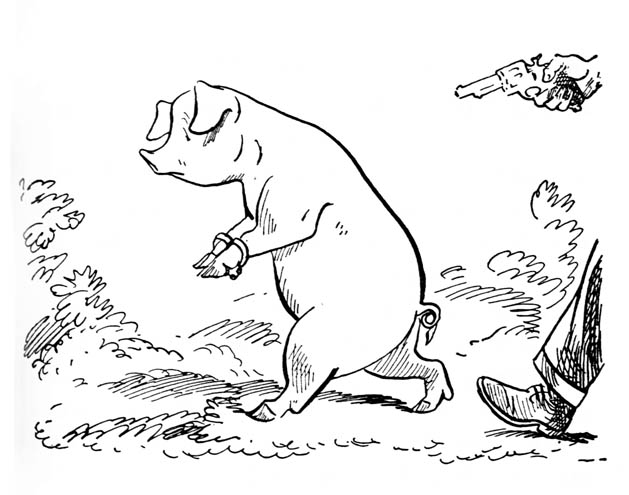

“OK.” Mr. Garble motioned up the hill with his pistol. “After you, my fat friend.”

“But-but why are we going this way?” Freddy asked. For he supposed that Mr. Garble would take him down to the farmhouse, then call the sheriff.

Mr. Garble showed his teeth in a sneering smile. “Why it’s such a fine day, that I thought we’d go for a little ride. And then, instead of being locked up in a stuffy jail, I’ve planned a trip for you. A nice long trip. You’re going to see the Great West—won’t that be nice?—Now get going!” he snapped.

So Freddy turned and went. He felt pretty sick. He wasn’t going to be any wanderer on the face of the earth. He was going to be nailed up in a crate and shipped off to Montana. This time Mr. Garble was going to succeed. For he didn’t see any escape. His verses seemed pretty silly now; instead of weeping, a wanderer pig ought to be kicking up his heels and singing for joy. But it shows how low he was that he didn’t give a thought to changing the poem.

In the meantime, Uncle Solomon after waiting to see in which direction Freddy went, had dived into the air and was winging it straight as an arrow for the cow barn. He was there in a matter of seconds. “Freddy is captured!” he called as he shot in the door. “Garble’s taking him up through the Big Woods toward Schermerhorns’. Up and after ’em! Come on—everybody out!”

There was no time to raise the flag and call the animals together. As the cows trotted out of the barn and started up the lane, the owl flew off to warn the dogs and Hank and Bill and whoever else was in the barnyard. But he didn’t think the rescue party could do much. Garble probably had his car somewhere near the Big Woods; he would have Freddy in it before they could catch him; and anyway, he had a pistol. There was one thing that might help, though. As soon as he had given the alarm, he started for Centerboro.

On the way he reproached himself bitterly, for he was really very fond of Freddy. “Solomon,” he said to himself, “you have been inexcusably lax and remiss and negligent. It was your duty to keep watch for the enemy; instead, you abandoned that duty for an argument about an inferior poem. You are a fool, Solomon; a corrupt and perfidious traitor, a rogue, a scalawag, and a black-hearted, pie-eyed dope.” It shows how upset he was that he used several slang words in his denunciation of himself.

When the owl flew in the office window, the sheriff was leaning back in his big chair with a toothpick in his mouth and his eyes closed.

“Sheriff!” Uncle Solomon called in his quick gabble. “Garble’s got Freddy! Come on—hurry up or we’ll be too late!”

The sheriff slowly took the toothpick from his mouth and said sleepily, and without opening his eyes: “Too late? You mean for church? Well now, that’s too bad. Guess we can’t go. Don’t want to disturb everybody, comin’ in late.” And he went to sleep again.

Uncle Solomon flew over and perched on his shoulder and gave a loud screech in his ear.

The sheriff started up. “Hey now, look,” he said, “that ain’t any way to act. I told you at breakfast, Looey, I didn’t think I’d ought to go today. On account of my Adam’s apple durin’ the singin’. I—” Then at last he caught sight of the owl. “Hunh!” he said in a puzzled tone. “You ain’t Looey.”

“No, and I’m not urging you to go to church,” said Uncle Solomon. “I am requesting in words of one syllable to hop to it! Garble’s captured Freddy.”

At that the sheriff finally woke up all over. And two minutes later, with the owl beside him on the front seat, he drove out of the jail gate.

The sheriff shouted above the noise of the engine. “If Garble’s kidnapin’ Freddy, I know where he’ll head for—his shack at the east end of the lake. His road crosses this one a couple miles up. If we’re in time we’ll cut him off at the corners.”

When they reached the corners there was no sign of Mr. Garble. Uncle Solomon circled up in a spiral, hovered for a moment then shot down again. “Something going on up this left-hand road. Can’t make out just what, but—” The rest of the sentence was lost in the roar of the engine as the sheriff swung the wheel to the left and shoved down the accelerator.

While all this was going on Theodore had not been idle. As soon as Freddy and Mr. Garble left the pool, he came out from under the bank, gathered his legs under him, and gave a leap that carried him up into the edge of the woods, a little to the left of where the others had entered them. Then he kept right on leaping. He looked like a little green ball bounding along through the trees. And as he bounded, he thought: “I hope P-Peter is in his den, and not off berrying. If he’s home, maybe we can head off gug, gug—I mean Garble and rescue Freddy.”

It may seem odd that Theodore stuttered even when he was thinking. But he said that he did it on purpose. “You see,” he said, “if I don’t stutter, then it doesn’t sound to me like me, and I think maybe it’s somebody else thinking, and then I get mixed up. But if I stutter, then I know right away it’s my own thought.”

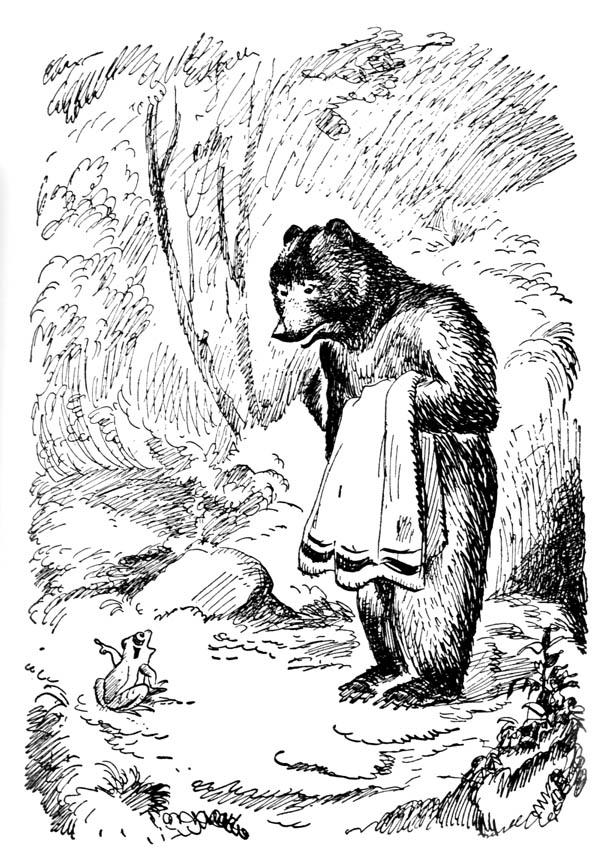

A frog can really travel when he gets into the swing of jump—gather your legs—jump—gather your legs—jump. Long before Freddy and his captor had got through the Big Woods, Theodore had reached the bear’s den. Luckily Peter was home. Since it was October, it was getting along towards his bedtime, and he was busy airing his blankets and pillows, but he left them hanging on the line and set out at a dead run. Even Theodore was left behind, for although bears look clumsy, they can gallop through the tangle of thick woods faster than you can run on the open road.

Luckily Peter was home.

And now there were three rescue parties, all headed towards Freddy from different directions. Peter reached him first. He came out of the Big Woods on the north, and there by the side of the old wood road was a station wagon, with the initials H.G. on the door. There was no one in it.

Peter looked at it. “I wonder what these things weigh?” he said. Then he went up to it, and bending down, put his big forepaws under the runningboard. And he was just about to heave the car over on its side when a voice shouted: “Stand away from that car!” and he looked around to see Mr. Garble pointing a pistol at him, while Freddy, with bright steel handcuffs on his fore-trotters, stood dejectedly beside him.

“A pistol!” said Peter. “H’m, that alters things, rather.” He got up and walked slowly towards Mr. Garble. “Good morning,” he said. “I was just looking—I thought you had a puncture in that rear tire.”

“Stand where you are, or your rear tires will get plugged full of punctures,” said Mr. Garble menacingly. “Get into the car, pig.”

As Freddy obeyed there was a crashing and trampling in the woods, and the Bean animals burst into the open a little way up the road and came galloping down on them.

Of course none of them knew that the pistol wasn’t loaded, and as Mr. Garble swung it to cover them while reaching for the doorhandle with his free hand, they skidded to a stop. They stood around him in a semicircle, the cows and goat with horns lowered, the dogs snarling, the cat with back arched and tail three times its natural size—even the placid Hank showed his long wicked teeth.

Nothing is more truly terrifying than the anger of animals. For when an animal snarls, or threatens with horns or claws, you know he just isn’t fooling. Freddy knew that in a minute they would rush Mr. Garble in spite of the pistol, and he called to them to stop. “Don’t do anything,” he said. “You’ll only get hurt.” Then it occurred to him that, as a pig about to be exiled, perhaps even executed, he was in an even more romantic position than as a lonely wanderer. He forced a brave smile. “Do not weep for me, my friends,” he said with simple dignity. “Though I go, never to return, think kindly of me when I am no longer among you. Do not think that I shrink from the fate that awaits me. (Golly,” he thought, “that’s a good start for a poem.) Tell them,” he said,—“tell them that I only did my duty, that—”

The sound of a horn interrupted his last words. Everyone turned to look, and saw the sheriff’s car coming up the road.

A look of consternation came over Mr. Garble’s face. Now he would have to turn Freddy over to the sheriff. And the pig knew too much. No one now was paying any attention to him; every eye was on the approaching car. Suddenly he whirled about. “Stop him! Stop thief! He’s trying to escape!” he shouted, and aiming his pistol at the pig, fired twice.

Mr. Garble would probably have fired again, but before he could pull the trigger a third time the sky fell on him. At least that was what it felt like. What had really happened was that at the first shot the animals had all turned and made a dive for him, and there he was with his face in the dirt and a good half ton of assorted animals on top of him.

The sheriff’s car stopped and he jumped out and ran up to them. By doing a good deal of yelling, and by grabbing, now an ear, now a horn or leg, and pulling hard, he finally got to the bottom of the heap and dragged Mr. Garble out. Mr. Garble was a mess. He was covered with dirt and his nose was scratched where it had been pushed into the road, and he really did look a lot flatter. He staggered over to the ditch and threw himself down.

Suddenly somebody said: “Hey, where’s Freddy?” and they all made a rush for the station wagon.

Freddy was lying on his back on the front seat with his eyes closed and his handcuffed fore-trotters folded across his chest. Not having known that the pistol was loaded only with blanks, he quite naturally thought that he was dead, and so he lay as still as possible. He was really very comfortable. “Probably,” he thought, “I am now a ghost, and tonight I shall go down and haunt Mr. Garble.” And he was thinking of all the different things a ghost could do to make Mr. Garble shake and shiver with fear, when there were a lot of voices around him, and two big paws lifted him up and carried him over to the grass by the roadside.

“That’s funny,” he thought; “you can’t pick up a ghost. Maybe I’m not killed—maybe I’m just mortally wounded.” Something wet splashed on his forehead, and he opened one eye to see the faces of all his friends looking down mournfully at him. “Oh, he does look so natural!” murmured Mrs. Wiggins, and another large tear rolled down her broad face to splash on his nose.

He tried to think of something noble to say, something that would be worthy to be quoted among The Last Words of Famous People. Unfortunately he had already made some appropriate and dignified remarks on getting into the car; these, if he said anything more, would become his Next to the Last Words, which would be silly.

However, something had to be said. He dodged another tear, and said to Mrs. Wiggins: “Old partner, we have come to the parting of the ways.” He smiled bravely. “We have had good times together, you and I. But at last the hour for me to leave you has struck—” He didn’t get any farther, for at that moment the cow burst into loud sobs.

When Mrs. Wiggins cried, she gave it everything she had. You could hear her for miles. The sheriff, who had been chuckling to himself over the act Freddy had been putting on, decided it was time to break it up. But he didn’t want to tell them that the pig hadn’t been shot at all, because he would be in for a lot of criticism around Centerboro if it got out that he had armed a deputy with a pistol loaded only with blanks. He went over and whacked the pig on the shoulder. “Come on, old partner,” he said with a grin. “The hour for you to get up on your hind legs has struck. You aren’t wounded; Herb didn’t even hit you. Which is a good thing for you, Herb,” he said, turning to Mr. Garble, “because law officers that shoot unarmed prisoners usually get put where they can’t do any more mischief. Come on, unlock these handcuffs.”

Mr. Garble got up with a groan and limped over to the car. “He was trying to escape,” he said. But nobody could hear him because Mrs. Wiggins had begun to cry in earnest now, and was making a terrific hullabaloo. The others were trying to explain that Freddy was all right, but she wouldn’t listen.

When the handcuffs were off, Freddy sat up and felt himself all over. “No bullet holes?” he said. “My goodness, Mr. Garble is an awful poor shot.”

“What?” shouted the sheriff, and Jinx put his mouth close to Freddy’s ear. “Go and let Mrs. Wiggins see you,” he yelled. “Maybe that will stop her. She’ll go on like this for hours if you don’t. And it’s Sunday, too.”

So Freddy went over and stood in front of the cow. After a minute she caught sight of him. She hiccuped twice and then stopped crying.

“I’m all right,” he said. “Garble didn’t shoot me.”

“Freddy!” she said. “You—you’re really …? Oh, how happy that makes me!” Then her face became sad again. “But how could you let me make such a spectacle of myself? All that about the parting of the ways, and the hour having struck—such dreadfully sad thoughts!” And she began to cry again.

“Come on, Freddy,” said the sheriff. “You’re my prisoner now, and I’ll have to take you down to the jail.” He glanced at Mrs. Wiggins. “She sure is fond of you, Freddy. There ain’t any people that would cry like that over me. Not any that could, anyhow.”

So Freddy said goodbye to his friends—without any noble phrases this time—and got in the sheriff’s car. Even through the noise of the engine they could hear, for quite a long time, the sound of Mrs. Wiggins’ grief, as Peter and her two sisters helped her on her homeward way.

That evening Uncle Solomon called at the jail. Freddy and the sheriff were playing checkers when he flew in the window. “Continue your game, gentlemen,” he said, perching on the back of a chair. “Don’t let me interrupt.” And then as the sheriff reached out to move a man: “No, no, sheriff!” he said. “Not that man; oh dear me, no!”

“Eh?” said the sheriff, and he leaned back and studied the board.

“By the way,” said Uncle Solomon, “I have been curious about a remark you made to me this morning. About the reason you hadn’t gone to church. Your Adam’s apple had something to do with it, did it not?”

“Oh,” said the sheriff. “Yeah. Why you see, if I go to church, I have to put on a necktie. ’Tain’t that I mind; it’s sufferin’ in a good cause. But I like to sing the hymns. Maybe that’s other folks’ sufferin’—I don’t know. Anyway a hymn starts, say, fairly low. OK, so I’m right with it; so I sing. Then the tune goes up a few notes. Up I go with it, and—well, I expect you ain’t got an Adam’s apple so you don’t know, but the higher the note, the higher your Adam’s apple climbs in your throat.” He lifted his chin and sang a scale to show them. “Everything’s all right so far, but what happens when the tune drops down again? My Adam’s apple gets caught on top of my necktie, and my voice stays up with it, and there I am singin’ four or five notes higher in the scale than the rest of the congregation, and off the key by that time, like as not. Well, that throws the other singers off, and they begin caterwaulin’ in six different keys, and then that throws the organ off, and—well, ’tisn’t fittin’. ’Tain’t the right kind of noises to be coming out of a church.” He leaned forward to move another man.

“Tut, tut!” said the owl sharply, and he drew his hand back again.

So Uncle Solomon thanked him for his explanation, and then turned to Freddy. “My purpose in coming this evening,” he said hesitantly, “was—er, to offer you a—” He interrupted himself to stop the sheriff again. “The king, sheriff; the king!”

“If your purpose,” said the sheriff with some irritation, “was to finish this game for me, sit down here and finish it!”

“No, no,” said the owl. “I beg your pardon; I’m a little upset this evening. No, my purpose—well, in fact I have written a short poem,” he said with a titter of embarrassment, “a modest effort, to redeem, in some measure, my shameful neglect of duty this morning.”

“Oh, forget it,” said Freddy.

“No doubt I shall. Our errors are easily forgotten. However, this poem is in the—the form of a missile—a missive, or epistle, I should say-addressed to you.” And he cleared his throat and recited.

“Remarkable pig:

Without ceremonial

May I offer to you this slight testimonial

To your wit and your wisdom, so often exhibited

On occasions where others are dumb and inhibited.

To your skill metaphorical, brilliance poetical,

Expertness rhetorical, and refinement aesthetical;

To your sharpness financial, your scope editorial,

Your feats on the gridiron quite gladiatorial.

And if anyone questions, or has the temerity

To doubt of your honesty, zeal or sincerity,

You have my considered permission to call ’im an

Enemy of

Your good friend,

Uncle Solomon.”

And having finished, he gave again the embarrassed titter and flew out of the window.

“Gee whiz!” said the sheriff.