The city of Erbil lies at the foot of the piedmont of the Zagros mountains in a strategic position which made it a natural gateway between Iran and Mesopotamia. At the same time its command of the rich alluvial plains to the west ensured a flourishing agricultural base; the emergence of a city in this location was inevitable.

Erbil now claims to be one of the oldest continually inhabited cities in the world, and not without reason: archaeological surface survey has indeed produced potsherds dating back to the Ubaid period (ca. 5500–4000 BC). This combination of prolonged occupation and strategic location marks out Erbil as an exceptional site. Within the context of ancient Mesopotamian civilisation there can be no doubt that it will have been one of the most important urban centres. Nevertheless, archaeological research of the remains has been limited. In the nineteenth century the early explorers of Assyrian archaeology passed through but their priorities lay elsewhere, whilst in the twentieth century a mixture of different research agendas and later inaccessibility combined to ensure that the mound of Erbil was never the target of a focused campaign. With the advent of the twenty-first century, however, the prospects look rather better. Scholarly interest in northeastern Iraq has been awakened and the logistic and political conditions are more favourable. Three archaeological assessments of the mound have been conducted, two in 1997 and 2010 focusing on surface survey and remote sensing1 and one in 2009 evaluating the significance of the remains within their historical context and evaluating how to approach archaeological investigations within the existing topography.2 The possibility of the citadel mound of Erbil being the target of the level of major fieldwork which it so richly merits now looks decidedly more real. In these circumstances the time seems ripe to gather together and evaluate the ancient sources on the city. This work is dedicated to the cuneiform sources.

The location of Erbil in north-east Mesopotamia between the Great and Little Zab rivers (courtesy Jason Ur).

Cuneiform writing

After a long and interesting prehistory, writing finally emerged in Mesopotamia a little before 3,000 BC.3 At first pictographic, the method of writing on clay with a triangular reed soon led to the evolution of the true cuneiform (wedge-shaped) script. This script was then in use until the first century AD, a period of over three thousand years. Over this immense time span the orthographics and utilisation of cuneiform underwent constant changes. From an initially logographic base the script rapidly became predominantly phonetic, evolving into the “mixed script” utilising syllabic signs, logograms and determinatives typical and characteristic of all primary writing systems. Although the determinatives remained relatively stable, the use of logograms varied greatly in different periods and places while the phonetic values of signs evolved continually. The physical appearance of the signs also evolved, generally becoming smaller and less complex over the centuries. The actual number of signs in normal use also gradually decreased. With regard to what the writing was used for, this also was continually evolving. From the origins as an administrative tool, cuneiform writing came to be used for letters, contracts, royal inscriptions, lexical texts, omen texts, literature, prayers, rituals, commentaries, mathematical and astronomical texts and so on. Then the decline set in. The fall of the Assyrian empire in the closing years of the seventh century BC resulted in the rapid disappearance of cuneiform writing in the north. In the south the process of cessation was more gradual. Following the end of the Neo-Babylonian empire (539 BC), cuneiform continued as a thriving medium for about two generations, after which here too it began to fall away. In both the north and the south the process was in any case already set in train by the infiltration of Arameans into Mesopotamia and the rise of Aramaic as the major spoken language of the region. By the Hellenistic period the use of cuneiform was essentially restricted to the temples, where scribal schools kept alive the literary tradition while continuing to utilise the script in administration. By the Parthian period the chief use of cuneiform tablets was in astronomical texts: the latest know cuneiform text is an astronomical almanac dated to 74–75 AD.

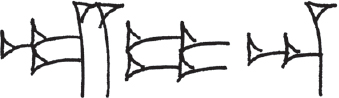

Development of cuneiform signs

The table shows a number of signs

(a) as they started out as pictographs in the fourth millennium,

(b) as they appear in cuneiform in the late third/early second millennium, and

(c) as they appear in the first millennium. The god sign depicts a star. When read as /du/ the foot sign means “to go”.

The language for which the writing system was originally invented was almost certainly Sumerian but from the latter centuries of the third millennium it was adopted for writing Akkadian, the other major language of ancient Mesopotamia. Traditionally Akkadian has been divided into two principal dialects, Assyrian in the north and Babylonian in the south, but the reality is that the picture is more complex, at any rate in the earlier periods. In the fullness of time the Mesopotamian cuneiform writing system was also employed for writing a number of other languages: these include Hittite, Hurrian, and Urartian. In other cases, Ugaritic and Old Persian, it served as the inspiration for new writing systems which are cuneiform in appearance but have no detailed relation on the level of individual signs.

Chronology

The periods in which the cuneiform (and pre-cuneiform) writing system was used in Mesopotamia are as follows:

Uruk |

4000 – 3000 BC |

Early Dynastic |

3000 – 2334 BC |

Akkadian |

2334 – 2193 BC |

Gutian |

2193 – 2120 BC |

Ur III |

2120 – 2004 BC |

Old Assyrian/Old Babylonian |

2004 – 1595 BC |

Middle Assyrian/Middle Babylonian |

1595 – 1000 BC |

Neo-Assyrian/Neo-Babylonian |

1000 – 612 BC |

612 – 539 BC |

|

Achaemenid |

539 – 330 BC |

Hellenistic/Seleucid |

330 – 126 BC |

Parthian |

126 BC – 224 AD |

As will be readily appreciated, for the earlier part of this scheme the dates are approximate. This is for three different reasons: (1) for the earlier periods the dates really come from archaeology rather than texts and are therefore tied to archaeological methods of dating; (2) at times of fragmentation changes in dynasties happened in different parts of the land at different times; and (3) uncertainties in the historical chronology. The situation for the latter can be summarised as follows:

First Millennium

In the first millennium there is no particular problem with chronology: dates can generally be assigned to the correct year.

Late Second Millennium

For the late second millennium, which is to say the Middle Assyrian/Middle Babylonian periods, we cannot be so exact. Constructing the chronology of this period is a complex problem involving the collation of data from Assyrian and Babylonian chronicles, historical inscriptions and administrative texts as well as comparisons with external (e.g. Hittite and Egyptian) sources. A final resolution of these problems has not yet been achieved although the degree of accuracy is slowly improving. As a rule of thumb it is currently possible to suggest dates for the reigns of the Middle Assyrian kings with an accuracy of plus or minus 10 years: in this work the dates for these kings are taken from Freydank 1991 pp. 188–189. However the picture remains more complicated than that as texts were actually dated by the yearly eponym (limu). In numerous cases we do not know to which reign an eponym should be assigned, and even when we do know the position in the chronology of that reign is often unclear.

Late Third Millennium/Early Second Millennium

For the late third and early second millennia the picture is even more complicated. There is as yet no generally agreed proposal for anchoring the dates of this period. Internally the chronology forms a coherent block from the rise of the Ur III empire (under Utu-hegal) through to the fall of Babylon (under Samsu-Ditana), although there are innumerable complications caused by the fragmentation of Babylonia prior to Hammurapi. This is a span of approximately 525 years. Attempts to fix this span in time have not so far succeeded. For many years faith was put in the so called “Venus Tablet of Ammi-Saduqa”, a record of sightings of the planet Venus. As Venus has a cycle of 56/64 years it was believed that one of three proposals would be correct: a Long Chronology (placing the fall of Babylon in 1659 BC), a Middle Chronology (fall of Babylon in 1595 BC) and a Short Chronology (fall of Babylon in 1531 BC). In the absence of conclusive evidence otherwise, many scholars settled on the Middle Chronology as a working compromise; the dates for this period given below are taken from this. More recently however the validity of the entire system has been questioned. A reappraisal of the evidence undertaken by a joint team from Ghent, Chicago and Harvard, taking into account both astronomical and archaeological evidence, came to the conclusion that local factors meant that the data had to be evaluated within an 8 year cycle and in fact came to the conclusion that the fall of Babylon can be dated to 1499 BC.4 Although this date is not yet in general acceptance, it is true to say that to many scholars a shorter framework is increasingly looking more plausible. Nevertheless, it is still not yet possible to give absolute dates for this time period.

Overview of the sources

Having established the framework in which we are dealing, let us now review the nature and distribution of the cuneiform sources at our disposal.

Uruk Period (4000–3000 BC)

This is when writing was emerging in Mesopotamia. The texts from this time are administrative together with associated lexical lists. There are no known references to Erbil from this time and indeed it would be surprising if there were. It is however possible that such texts will have been generated in Erbil and may one day be found by excavation.

Early Dynastic Period (3000–2334 BC)

The same holds for the Early Dynastic period: no texts referring to Erbil are currently known but it is to be expected that with excavation this could change.

Akkadian Period (2334–2193 BC)

This is when Erbil enters history. Erbil is mentioned first in some documents from Ebla dating to shortly before the destruction of that city, contemporary with the early Akkadian period in Mesopotamia. The fact that large parts of Mesopotamia were in fact brought under the control of the Akkadian administration means that it is quite conceivable that references to Erbil may one day come to light in texts from elsewhere.

By the reign of Šar-kali-šarri, the fifth king of the Dynasty of Sargon, the Akkadian empire was falling apart.5 The territory of Akkad was fragmented, in part overrun by the Guti, a people who by the Old Babylonian period were seated in the mountainous region northeast of the lower Tigris, but who in the third millennium may have been localised in the mid-Euphrates area and/or northern Babylonia. The chronology and events of this period are very unclear. Erbil is mentioned in an inscription of the Gutian king Erridu-Pizir as an objective of a military campaign. This inscription is written in Akkadian.

Ur III (2120–2004 BC)

The expulsion of the Gutians by Utu-hegal led to the foundation of the Ur III empire which at its maximum extent constituted a multinational state ruling the greater part of Mesopotamia. It is not known whether or not Erbil had regained its independence from the Guti but it was in any case taken by both Shulgi and Amar-Sin and incorporated within the empire. The year names for Shulgi year 45 and Amar-Sin 02 refer to these events. In addition to this the city is referred to in a votive inscription from the time of Šu-Sin and in a number of administrative texts. These texts are written in Sumerian.

Old Assyrian/Old Babylonian6 (2004–1595 BC)

There are two known references to Erbil from this time, both royal inscriptions, stelae of Dadusha and Shamshi-Adad. Both these inscriptions deal with the same joint campaign which these kings conducted in the northeast of Mesopotamia. Erbil at this time was part of the kingdom of Qabra and is likely to have been home to an indigenous temple and/or palace administration. An indication of what this may have been like is given by the tablets from Shemshara (on the Lower Zab) which do stem from the palace administration of an outlying regional kingdom of just this time.7 Both stelae are written in Akkadian.

Middle Assyrian (1595–1000 BC)

With the Middle Assyrian period both the quantity and variety of sources at our disposal increase. Erbil is mentioned in three royal inscriptions, a votive inscription and approximately forty-five administrative texts. For the first time we are able to formulate something more than a one-dimensional image of the city. These texts are written in Akkadian.

Neo-Assyrian (1000–612 BC)

In the Neo-Assyrian period there is a huge increase in the range and quantity of the sources and the detail of information they provide. The sources include chronicle entries, royal inscriptions of seven different kings, oracular pronouncements, reports on divination, hymns, a cultic commentary, a votive inscription and altogether over 150 letters and administrative texts. Together these texts cover campaigns and victory celebrations; building work and rites in the principal temple of Ištar of Arbail in both Arbail (the Egašankalamma) as well as her countryside shrine at Milkia (the Egaledinna), together with information on royal donations, temple staff, offerings and rituals; the construction of a canal bringing water to the city; provincial administration including military organisation, the receipt of tribute and taxes, and the sending of dues to the temple of Aššur; and loans, contracts and records of judicial decisions. These texts are all written in Akkadian. We also have the first surviving depiction of the city in the form of sculptured reliefs from the North Palace and the Southwest Palace of Nineveh as well as representations of Ištar of Arbail herself on seals and amulets and on a stele from Til Barsip.

Bronze amulet of Ishtar of Arbail. The goddess stands on her vehicle, a lion, with her face turned towards the onlooker. A worshipper stands in front of the image. Other representations of the Ishtar cult statue show her looking straight ahead, as was almost certainly the case in reality (British Museum, London – BM 119437).

Neo-Babylonian Empire (612–539 BC)

The Neo-Babylonian Chronicle mentions that Cyrus crossed with his army below Erbil at the outset of his campaign in 547 BC. Apart from this there are no known references to Erbil in the Neo-Babylonian sources. As this is a time from which tens of thousands of administrative documents survive, this very silence suggests that the city did not form part of the Neo-Babylonian empire. The chronicle is written in Akkadian.

Achaemenid (539–330 BC)

Darius’ inscription at Behistun records that he hunted down and impaled the rebel Shitrantakhma in Erbil (the Behistun inscription itself is trilingual, with versions in Akkadian, Old Persian and Elamite, and the text was also disseminated in Aramaic). There is one reference to Erbil in Akkadian administrative texts, in addition to which there are some unpublished citations which may refer to the city in administrative records from Persepolis written in Elamite; Erbil is also mentioned in the “Passport of Nehtihor”, an official permit written on leather in Aramaic.

Hellenistic/Seleucid (330–126 BC)

Guagamela, where Alexander the Great defeated Darius III, was located in the plains northwest of Erbil and Alexander briefly visited the city after his victory before taking the road to Babylon. Although Alexander does appear in cuneiform texts of the time, including a reference to his entering Babylon, there are no known references to Erbil in the cuneiform documentation from this time.

Parthian (126 BC – 224 AD)

There are no known references to Erbil in the cuneiform texts from this period.

To summarise, there are a number of references to Erbil in Eblaite and Sumerian administrative texts of Akkadian and Ur III date and hundreds of references in Akkadian texts from the second and first millennia. Remarkably, only two of these inscriptions appear to have actually come from Erbil and even one of these is questionable. The votive statuette of Šamši-bel was evidently dedicated to Ištar in the Egašankalamma but actually found near lake Urmia whither it had presumably been taken as booty. This leaves the inscription of Ashurbanipal K891 as the sole cuneiform text which may have actually been found in Erbil and even this attribution is based on a note accompanying the original publication which is open to interpretation. There are a handful of references in unpublished Elamite texts from Persepolis. In Old Persian the city only appears in the corresponding version of the inscription at Behistun. There are no references in Hittite, Hurrian, Urartian or Ugaritic sources.

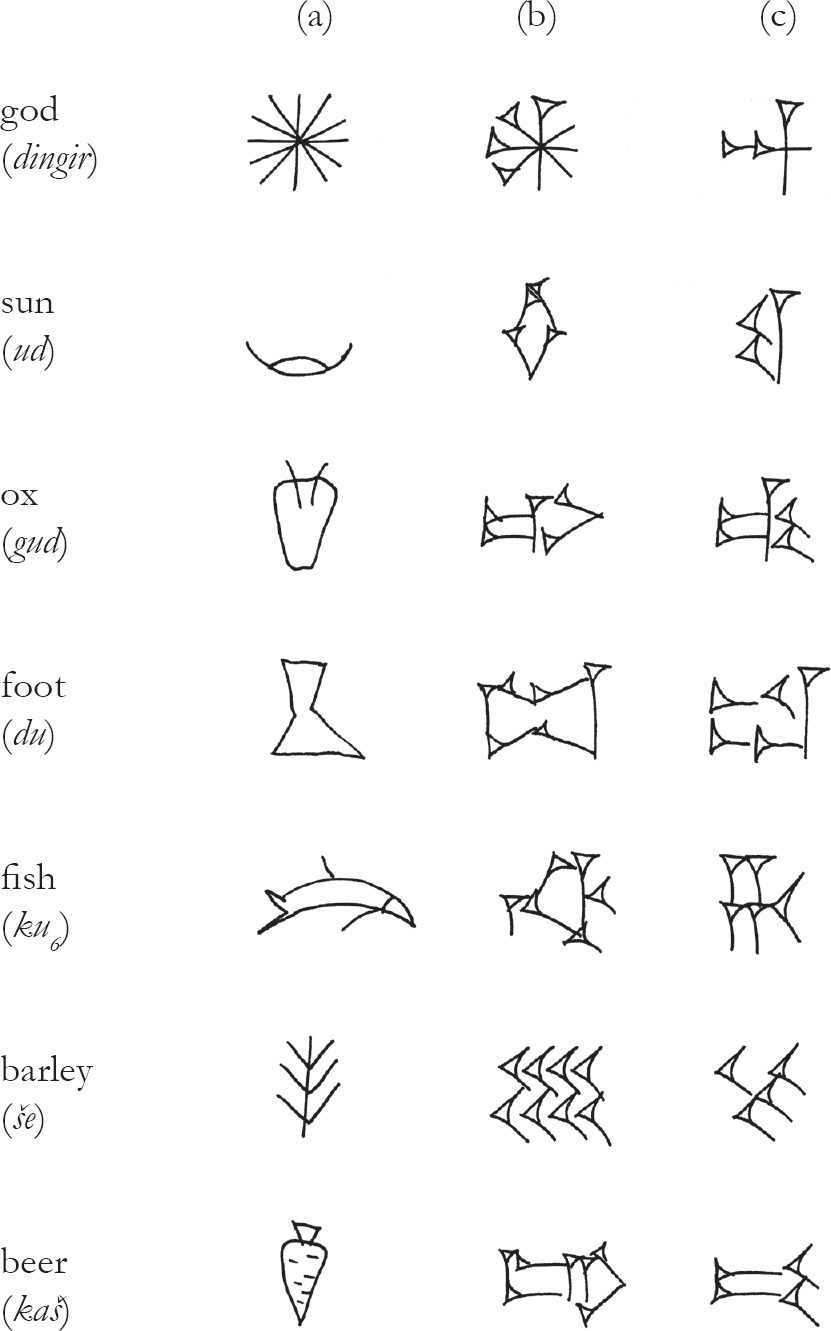

Due to the workings of the cuneiform writing system there are numerous different ways of writing the name of the city, furthermore this developed over time due to (1) the evolving pronunciation of the name, (2) changes in the usage of signs and (3) changes in the way individual signs were written. The four examples here span the late third to the early first millennium. In detail:

(a) |

late third millennium: ur-bí-lumki (from the Ur III text CT 32, 26) |

|

|

(b) |

early second millennium: ur-bi-elki (from the Stele of Dadusha, Old Babylonian) |

|

|

(c) |

late second millennium: uruAr-ba-il (from the Middle Assyrian text KAJ 178). |

|

|

(d) |

mid first millennium: uru4–DINGIR (from the Neo-Assyrian text SAAB 2 72). |

|

|

Over this period of cuneiform documentation the rendering of the city’s name progresses from Irbilum in the Ebla texts, to Urbilum in the Ur III sources, to Urbēl in the Old Babylonian sources and on to Arbail in the Middle and Neo-Assyrian sources. The understanding that the name means “(city of) four gods” is an erroneous folk etymology deriving from a literal interpretation of the fact that from the Middle Assyrian period onward the city’s name could be written using the cuneiform signs for “four” and “god”. But this writing is simply a scribal shorthand as the signs are actually being used for their phonetic contents: in Akkadian “four” is erbe (or arba) and “god” is il(u), hence a way of writing Erbil (Arbail).

We turn now to a more detailed analysis of what these sources have to say.

1. Novacek 2007. Preliminary surface survey utilising GPR took place in 2010, see Colliva 2011.

2. MacGinnis 2009.

3. See Walker 1987 for an excellent survey on the history and development of the cuneiform writing system. For general surveys of the archaeology and history of ancient Iraq see Roux 1993 and Foster & Foster 2009.

4. Gasche et al. 1998: pp. 72–73 for the evaluation of the Venus Tablet.

5. The Akkadian dynasty did in fact linger on for another forty years or so; the last king of the dynasty that we know of is Šu-Turul (2168–2154 BC) though there is at least one king, Li-lu-ul-DAN (see Frayne 1993 p. 218) whom we cannot place and it cannot be ruled out there may have been further petty successors whose inscriptions have not yet been recovered.

6. This period in question might equally be labelled Old Babylonian or Old Assyrian - the former because the events involved fit into the history of the region recorded in sources written in Old Babylonian, the latter because the region is later to become an unquestionable part of Assyria. The distinction is to some extent artificial and until sources are recovered from Erbil itself the matter is somewhat academic.

7. See Eidem 1992. Eidem and Laessoe 2001.