Bad Aircraft and Bad Luck

‘I’m very keen for a scrap in the air, for I feel quite confident that I shall be able to take care of myself alright with a machine gun.’

– William A. Bishop1

As early winter dragged on, Billy Bishop had sky-high hopes that 21 Squadron would soon be assigned to a frontline aerodrome in France. And it was wonderful news to him – a first step in that direction – when the squadron was equipped with the latest two-seat reconnaissance, bombing and escort aircraft: the Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.7.2 After Billy saw the first new aeroplanes at Netheravon, he wrote to Margaret Burden:

‘We are to be ready to fly over [to France] by December 24th [1915]. But the way things happen in the Flying Corps, it will probably be a fortnight after that before we go … Our new service machines, R.E.7s, are arriving now every day. They are lovely things, the biggest machines made, [and] awfully powerful and comparatively safe. They will carry a 600-lb bomb.’3

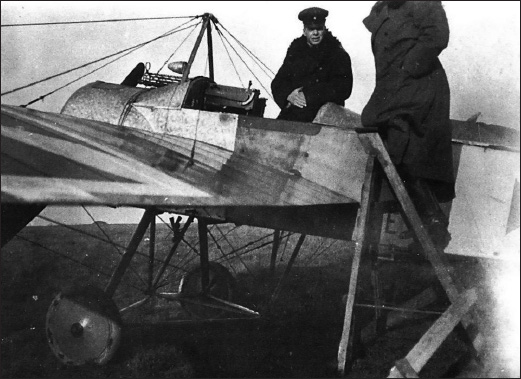

Royal Aircraft Factory R.E.7 (serial number 2353), one of 100 of the type produced by the Siddeley-Deasy Motor Co. Ltd. Billy Bishop flew to France in this type aircraft and then flew in it as an observer with 21 Squadron. (Cross & Cockade International)

But squadron aircrews soon became apprehensive about the R.E.7’s air defensive capability. At the time, Germany’s Fokker E.I monoplane was the only front-engine ‘single-seat … fighter fitted with a mechanism to allow machine-gun fire through the propeller’4 arc without damaging the blades. In response to this threat, the R.E.7 observer was placed in the front seat with a side-mounted flexible .303-calibre Lewis machine gun. But his field of fire was limited by bracing wires between the wings, as well as by struts supporting the upper wing over the fuselage. In short, the observer was unable to use the Lewis gun effectively. 5 The pilot, placed in the more spacious rear seat, was armed with a rifle or pistol.6 In the R.E.8 and other later British aircraft, pilots sat in front and observers occupied rear cockpits.

Preparing for Battle

For the moment, however, all squadron members were focused on the much-awaited deployment to the Western Front. Once the new aeroplanes were gathered at Netheravon, aircrews made training flights on every good day in a season better known for poor flying weather. Despite the R.E.7’s limitations, Billy remained optimistic:

‘Yesterday was glorious and at noon Johnson [a pilot] and I set out in [a] new machine for a long cross-country [flight]. We went half-way [to] the other side of London … and then on account of dense fog we turned back … [It was] quite a long flight and after attaining a height of 10,000 feet … it took twenty minutes to come down in a steep spiral.

‘The Major [Frederick W. Richey7] is in France, making final arrangements … Lord, I’ll be glad to get over [there], I’m very keen for a scrap in the air, for I feel quite confident that I shall be able to take care of myself all right with a machine gun …’ 8

A year earlier the popular feeling was that the war would be over by Christmas 1914. But the vast battleground that Billy saw on his first flight to St. Omer in late-October 1915 convinced him that the conflict would last for a long time. At the moment he sought a lively holiday party as a proper send off. His thoughts conveyed to Margaret on Christmas Day 1915 may have been overly candid, but he surely felt he could give her a realistic picture of life in London without inferring he participated in it:

‘Merry Xmas, much merrier [where you are] than it is here. I came up [to London] last night and went to the Carlton for supper … [Another officer and I] are going to the Regent Palace Hotel and watch the [carefree] life there. I might say it is about the most cosmopolitan spot in England. It is full of people on what are called here “weekend honeymoons” and the grill and restaurant are full of love girls and men who are picking them up. It is one of the most amusing spots in town and the only place that doesn’t look like a cemetery …’9

When 21 Squadron did not embark for France at Christmastime, New Year’s Day became the next speculation point. Billy stopped worrying about it. He had already been awarded his observer’s insignia, which conveyed a certain air of authority among the student observers. But, military bureaucracy being somewhat slow, the well-earned honour was not officially recognised until 15 November 1916, but ‘with seniority from 18 January 1916’.10

To begin the new year. Major Richey ordered all squadron members to remain at Netheravon while preparing for their departure to France; each R.E.7 had to be flown for six-hours’ duration. On Sunday, 9 January 1916, Billy was up in an aeroplane for only an hour when:

‘[A] dense mist closed in and we ran for home, only being able to see about 200 yards in front of us. Suddenly another machine appeared, heading straight for us. Oh Lord, I was scared; I thought we were gone. But he dived and we zoomed, and we missed [each other] by a few feet. I’m shaking yet …’11

Billy Bishop wearing his RFC tunic and winged-O observer’s insignia. (War Amputations of Canada)

Off to France

At long last, at 7:00 am on Saturday, 15 January, all of 21 Squadron’s equipment was packed into what Billy described as ‘about sixty lorries, tenders and touring cars, and a flock of motorcycles’. They all headed toward Avonmouth, on the Severn estuary, at the mouth of the River Avon. The following day a transport ship loaded with the unit’s equipment sailed out into the ocean and then swung eastward for France. Meanwhile, Billy led a contingent of men to Southampton to join up with other squadron members for the same journey in another ship. 12

By Tuesday, the 18th, Billy had endured a rough sea voyage and was billeted at ‘a nice little hotel [in Rouen], quite Bohemian sort of place, but very nice and clean’. In his first letter from France he wrote: ‘Talk about mud! Salisbury is like a dried up desert compared to this [region]. But nobody cares as long as we are here. It is too funny for words, talking pigeon French and trying to be understood.’13

The following day, 21 Squadron had the distinction of being the ‘only unit to go to France equipped [entirely] with R.E.7s’.14 The unit arrived at Boisdinghem15 in northern France, west of St. Omer on Sunday, 23 January 1916. Later that day, Billy wrote to Margaret from a hospital near the aerodrome, where he had been admitted after becoming very sick while accompanying squadron equipment to the new location:

‘The doctor refused to let me go on by road, so I came here yesterday by train and, after seeing … Major [Richey], I came to this hospital. Continual wet feet, I suppose, knocked me out, so here I am for today and tomorrow … From my window I can see aeroplanes circling around, very high up. They are patrol machines … waiting in case a German crosses the lines, to attack him. It is absolutely a perfect day, not a cloud in the sky. I wish I were outside, [and in] another day or so I shall be. It is such a wonderful chance, flying over here; the opportunity of a lifetime, to see the whole show from miles above.

‘Darling, I am a long, long way from you now, but perhaps nearer than [when] I was in England … for a lucky shot may send me back to you.

‘Our new aerodrome is about six miles from here, and between twenty and twenty- five miles from the lines. I haven’t seen our billets, but they say they are very nice, so we are in luck, as some are awful, from what I hear.’16

Royal Flying Corps general headquarters (GHQ) was also located at Boisdinghem and it required ‘special strategic and patrol work … [which] was the duty of two squadrons (12 and 21) retained at Flying Corps headquarters’.17 By Wednesday, 26 January, Billy was out of the hospital and preparing for his frontline duties. But, first, he settled into his living quarters – in expropriated civilian houses – about which he wrote:

‘We are in billets here, two [officers] in a room … My billet is just across the road from our flight mess, which is in a room in another house. In it we have a fire [-place] and a gramophone, which is a great comfort in the lonely evenings. Our aerodrome is quite a good one and is only about a hundred yards away, so we are quite well placed.’ 18

The Fokker Scourge

Now close to the frontlines, Billy began to hear more about air combat and learn about his future adversaries. One piece of chilling news was the 12 January loss of an R.E.7 flown by 12 Squadron19 – most likely shot down by the early German fighter ace Leutnant [Second- Lieutenant] Oswald Boelcke20 in a Fokker monoplane. According to an RFC report, the R.E.7 had been escorting a reconnaissance patrol21 when it was attacked by the superior German aeroplane. Two days later, RFC general headquarters issued an order, ‘which brought about, at a stroke, one of the drastic changes in the air war – formation flying …’22 It stated:

‘Until the Royal Flying Corps are in possession of a machine as good as or better than the German Fokker it seems that a change in tactics employed becomes necessary. It is hoped very shortly to obtain a machine which will successfully engage the Fokkers … In the meantime, it must be laid down as a hard and fast rule that a [British] machine proceeding on reconnaissance must be escorted by at least three other fighting machines. These machines must fly in close formation and a reconnaissance should not be continued if any of the machines become detached … From recent experience it seems that the Germans are now employing their aeroplanes in groups of three or four, and these numbers are frequently encountered by our aeroplanes. Flying in close formation must be practiced by all pilots.’23

Oberleutnant Oswald Boelcke, an early, highly successful Fokker Eindecker pilot, with his aeroplane. Note the forward-firing synchronized machine gun protruding over the cowl. (Dr. Lance J. Bronnenkant)

Frontline personnel had to submit correspondence to a local area censor – and, indeed, Billy was assigned to that duty on occasion. Consequently, he did not share all of the news with Margaret, but did mention other information he learned about life at the Front:

‘An arrangement has been made with the German flying corps and our own, by which if a [British] machine goes down behind the German lines, as soon as possible a German machine will come back and drop a message telling whether the pilot and observer are killed or wounded and [if the latter] how badly. If killed they [will] enclose a photograph of the grave and we [will] do the same for them. It is awfully nice to be on such good terms with one’s enemies, and everyone here speaks very highly of all the German flyers. They seem to all be of a fine crowd.’24

Flying in the R.E.7

Billy Bishop showed no fear of German aircraft when he and Lt Roger Neville, later a five-victory fighter ace25, made a flight over the lines in their R.E.7. Billy wrote:

One RFC response to the ‘Fokker scourge’ was the rear-engined Airco D.H.2 which allowed the pilot an unobstructed forward field to use his machine gun. The aeroplane seen here was captured on 9 August 1915. (Dr. Volker Koos)

‘We are having a lot of trouble getting our machines to leave the ground. It is so muddy that the wheels sink right in and if the machine is at all heavily loaded it simply won’t rise … we are really in an awful state, not knowing what to do about it. We simply have to get up somehow, and the sun so seldom appears that the ground stays wet.’ 26

Years later, Billy amplified that early memory:

‘[We] gunned across our own aerodrome at least a dozen times, trying to get off into the wind, then taxied back to try again, before anyone realised that we were asking too much of the aircraft. Consultation between senior officers followed and it was decided to move to the larger field at St. Omer … in hopes that with a larger run the R.E.7 might consent to struggle into the air. Before this decision was taken we had even tried to take off without the bomb and failed.

‘So the young observer and four machine guns were ferried to St. Omer by truck, while the pilot brought the R.E.7 across country minus its bomb. At St. Omer, with myself and four Lewis guns added, we got off, the guns being mounted on four pegs on the forward cockpit rim. The bomb was simply left behind, since the ’plane utterly refused to lift it.’27

Billy’s repeated mention of problems with the 500-lb bomb ignored the fact that the first R.E.7s, powered by a 120-horsepower engine, could not carry such a heavy explosive device. According to British aviation historian J.M. Bruce, that aeroplane was intended to fly bearing ‘one 336-lb Royal Aircraft Factory bomb or two 112-lb bombs augmented by 20-lb bombs’.28 As for the aeroplane itself, Roger Neville considered it ‘hopeless’ and ‘outdated before it arrived in France’. He also stated that the designation ‘R.E. stood for Reconnaissance Experimental and the 7 meant, according to cynics, that the previous six had failed to get off the ground’.29

Commenting on this mission, Billy later heaped further abuse on the aeroplane:

‘[Eventually it] … got into the air, although hours must have elapsed as we circled around and around St. Omer until we had attained an altitude of 6,000 feet and could set off toward the lines. There I had my first taste of ack-ack [anti-aircraft] fire and I remember it was hard to take, though later I felt completely [like] a hero for having come through this visit to the baptismal font of war …

‘Ack-ack or no ack-ack, however, we slipped across the enemy lines, visited the German batteries, the locations of which [our] artillery wanted to take down, took photographs (praying the while nobody would catch us at it and want to discuss the matter), and sneaked home …’ 30

There is a question, however, as to whether that undated mission with Roger Neville was Billy Bishop’s first flight over the lines in an R.E.7. Such a difficult flight in that aeroplane no doubt occurred and Neville is mentioned in subsequent correspondence. But on Saturday, 29 January, Billy flew with a Lieutenant Hunt on an artillery-spotting sortie that may have been his initial combat flight from Boisdinghem. He described that mission to Margaret in terms much more charitable to the R.E.7:

‘At last my flying in France has really commenced. Yesterday [the weather] quite suddenly cleared up and off I went with Hunt. Very funny, too, [as] it was the same job … I had here last October, only much more exciting this time. At one time, while doing some dodging to keep altering the aim of the guns, we attained such a terrific speed that the engine could hardly be heard on account of the screaming of the [aeroplane’s bracing] wires. We were diving almost vertically, with the engine full on, so it is little wonder. However I enjoyed it much more than I did last time.’31

Introduction to ‘Archie’

Adding to the minor mystery of the first R.E.7 combat flight – an example of the difficulty in understanding conflicting accounts about Billy’s various activities – a letter a few days later contained his first mention to Margaret of German anti-aircraft fire:

‘Today … it was clear as a bell with a terrific wind blowing, but we all went [up] on various expeditions. Mine was a three-hour look [around for] Hun machines. Thank God I didn’t see any.

‘[At one point] a strange machine appeared above and behind us. He evidently thought we were Huns, but fortunately discovered the [British cockades] on our [wings] in time. I was just about to open fire on him with two machine guns, as I couldn’t see his markings, either. But after that we both swerved and missed each other. And … about two minutes after [that], we were both targets of “Archibald” [anti-aircraft fire] from behind the German lines. Fully fifty shells were bursting in the air at one time, near us … A friend of mine from Netheravon was shot down an hour later by a Fokker … near the same place. I’m glad [the German pilot] didn’t see us.’32

Alerted to the approach of Allied airmen, German Flieger-Abwehr-Kanone [Flak] crews run to their anti-aircraft guns in an effort to stop the intruders. (Bayerisches Hauptstaatsarchiv Militärarchiv Munchen/Staudinger photo 017850)

It is worth noting that ‘Archibald’ – or, more commonly, ‘Archie’ – became the accepted British term for any of several anti-aircraft gun types to fire explosive rounds that detonated at the expected altitude of opposing aircraft. The word appears often in 1914-1918 War literature and lore. The official history of the Royal Air Force in World War I, The War in the Air, referenced in this book’s bibliography, noted that the name ‘Archie’ came: ‘from a light-hearted British pilot, who, when he was fired at in the air, quoted a popular music-hall refrain – “Archibald, certainly not!”’33

No British air casualties were recorded that day. Indeed, the RFC daily report noted only that ‘[3rd] Army reconnaissance escort machines were attacked by a Fokker which, however, made no attempt to come closer than 500 yards’.34 One has to wonder whether Billy’s friend had been luckier than reported or whether the report Billy heard had been based on misinformation – or imagination.

Almost a week later, Billy recounted another R.E.7 flight for Margaret’s benefit:

‘This morning … Neville and I went over the lines. There were machines all over the place, about twelve in sight at one time. I nearly had nervous prostration trying to watch them all at once. It is so hard to tell whether they are friend or foe, [they] approach so rapidly. One has to keep training his guns on every machine that approaches. On the way home a big Hun Battleplane started to chase us, so I trained my guns on him, and waited for him to get [within] range, which is about 400 yards. It is only a waste of ammunition to fire from farther away, with machines going about 100 miles an hour. Then, just as he got in the right place, one of our Battleplanes came swooping down and he turned and fled, with the two of us after him. Then the “Archies” started on us and [were] getting very accurate, [and so] Neville and I headed for home full tilt. They wasted a lot of ammunition on us and didn’t touch us at all. This all occurred two miles on the German side …

‘Then after we got back, I realised for the first time that [today] is my twenty-second birthday. Dearest, I greet you.’ 35

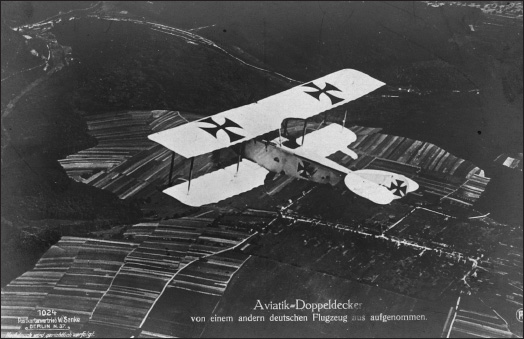

Billy Bishop and Roger Neville may have been involved briefly with the German aircraft mentioned in the 8 February RFC War Diary report: ‘The 2nd Army reconnaissance [mission] was attacked by two Fokkers and two Aviatiks. They were driven off. Hostile anti-aircraft guns were also very active, [a] 2nd Army reconnaissance machine being damaged.’36

A popular German postcard of the time depicted an Aviatik C.I of the type that Billy Bishop and Roger Neville drove off. (Author’s Collection)

But that encounter was mild compared to what the weather did to Billy the following day:

‘This morning I went up for a three-and-a-half hour patrol and it [was] the coldest day I have seen here … I got my right cheek quite badly [frost-bitten]. It has swelled up and blistered and burst, which they say is a good thing, but … it is extremely painful. The worst of it is that it will stop my flying for some days. I am spending the night in hospital on condition they will let me go tomorrow, because if I stay any longer they will cable home and then you will all worry, which there is no cause to do at all…’37

A flight of R.E.7s outside their tent hangars preparing for a mission over German lines. (Stewart K. Taylor)

More Misfortunes

Despite his protestations, Billy had to remain in hospital a day longer than he had planned. When he returned to duty he saw another demonstration of natural forces:

‘Yesterday … we were chasing Boches38 all day long. The wind was right for them, i.e., blowing from our side of the lines to theirs and giving them a chance to get back [to their own lines] quickly. Quite a lot [of them] came over, probably because there seems to be a general [German] liveliness all along the line …

‘Today there was a sixty-mile-an-hour gale blowing at 3,000 feet. It was hopeless to fly much higher … and so the day was spent in wireless work near the aerodrome.’ 39

Earlier that morning, the War Diary reported, ‘the gale overturned all the iron hangars of 20 Squadron at Clairmarais, wrecking three F.E.2 [two-seaters] and seriously damaging three lorries.’ 40

The next day all RFC flying was cancelled due to damage caused by the gale-force winds.41 But 21 Squadron was not affected – much to Billy’s dismay:

‘This has been a terrible day, raining and blowing like mad. All the tents on the aerodrome have been blown down and are in shreds. Fortunately, our [aircraft] are in hangars so they are safe, though we wish they had been blown to shreds, too, because they are really the [ones] easiest hit out here and are not a success, being too cumbersome. When we smash these [R.E.7s] we shall probably get better ones, of another type, and faster.’ 42

The strain of combat took a toll on Billy, as Roger Neville observed:

‘After he had been in operations in France for a time he became noticeably more moody and frustrated, the limitations of the R.E.7 as a combat machine became more and more apparent … [He] was boiling with rage because he could not fire back without danger of shooting off the R.E.7’s tail-plane or his pilot’s head. He was a very fine shot … Yet inevitably all his keenness made pilots wonder when his enthusiasm was going to overcome his judgement.’43

The R.E.7’s operational problems led 21 Squadron to be withdrawn from frontline work. The unit’s next assignment was flying aerial defence missions over St. Omer, site of the GHQ of General Sir Douglas Haig, commander-in-chief of the British Expeditionary Force. Over a quarter-century later Billy recalled ‘flying in … the freezing mist of a Pas de Calais February … Fortunately, the enemy did not seem to know we were there … Presumably, we would have tried to join issue with the Hun if he had come along and, I imagine, [would] have been shot down ingloriously for our pains …’44

On 9 March 1916, six of 21 Squadron’s F.E.7s joined in a bombing raid behind German lines and it was a miracle that none of the unit’s crews were among the mission’s casualties. 45 Billy’s letter to Margaret revealed mood swings that accompanied his combat fatigue; apparently, he was so distraught that he could not even bear to use the perpendicular pronoun in describing his misery:

‘In the air you feel only intense excitement. You cheer and laugh and keep your spirits up. You are all right just after you have landed as you search your machine for bullet and shrapnel holes. But two hours later, when you are quietly sitting in your billet, you feel a sudden loneliness. You want to lie down and cry.’46

That low point was followed and, no doubt, compounded by a series of mishaps over the coming weeks. Near the aerodrome, Billy was driving a small motor vehicle when he ‘collided with an army lorry and was severely shaken up’.47 Days later, he was inspecting his aeroplane when ‘a supporting cable struck his head and left him unconscious for two days’.48 Then a recently-extracted tooth became infected, resulting in another hospital stay. And, when Roger Neville pranged an aeroplane while landing, Billy slammed forward and ‘cracked his knee against a metal bracket.’49

Another traumatic event occurred on Tuesday, 2 May 1916, after he took a Channel steamer from Boulogne to Folkestone for a much-needed three-week leave. As he left the ship to go ashore, Billy ‘slipped on the gangplank and stumbled forward on the concrete pier with three other men on top of him’.50 He landed on the same knee injured in the recent crash with Neville.

During Billy’s subsequent stay at the RFC Hospital in Bryanston Square in London, on Friday, 26 May, he received formal notification that ‘the general officer commanding London district has been directed to cause a medical board to be assembled shortly to report upon the state of your health’.51

The order portended an extended stay in London. It would either mark the end of his flying career or provide an opportunity for him to find someone to help him enter a pilot training programme.