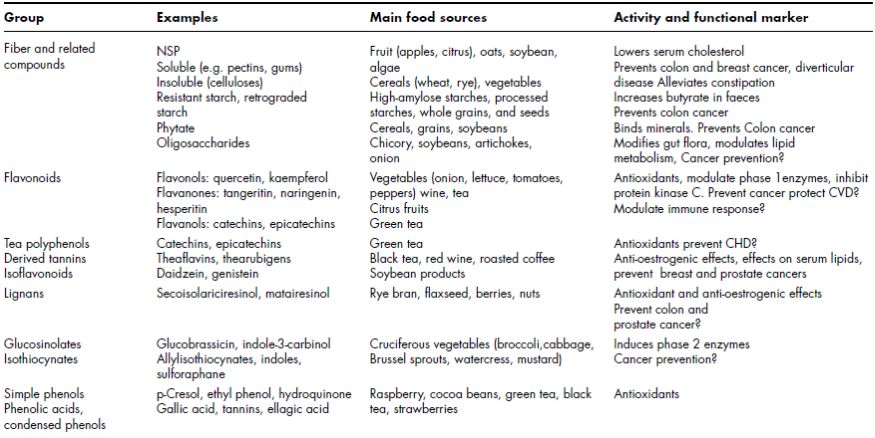

Figure 2.1 Classification of phytochemicals.

2 Chemistry and classification of phytochemicals

The word ‘biodiversity’ is on nearly everyone’s lips these days, but ‘chemodiversity’ is just as much a characteristic of life on Earth as biodiversity. Living organisms produce several thousands of different structures of low-molecular-weight organic compounds. Many of these have no apparent function in the basic processes of growth and development, and have been historically referred to as natural products or secondary metabolites. The importance of natural products in medicine, agriculture and industry has led to numerous studies on the synthesis, biosynthesis and biological activities of these substances. Yet we still know comparatively little about their actual roles in nature.

Clearly such research has been stimulated by scientific curiosity in the substances and mechanisms involved in the protective effects of fruits and vegetables. Dietary phytonutrients appear to lower the risk of cancer and cardiovascular disease. Studies on the mechanisms of chemoprotection have focused on the biological activity of plant-based phenols and polyphenols, flavonoids, isoflavones, terpenes, and glucosinolates. However, most, if not all, of these bioactive compounds are bitter, acrid, or astringent and therefore aversive to the consumer. Some have long been viewed as plant-based toxins. The analysis of phytochemicals is complicated due to the wide variation even within the same group of compounds, and the metabolic degradation or transformation that may occur during crushing or processing of plants (e.g. for Allium and Brassica compounds), thus increasing the complexity of the mixture. Many phytochemical analyses require mass spectroscopy and therefore are time-consuming and expensive. Furthermore, some compounds tend to bind to macromolecules, making quantitative extraction difficult. Furthermore, many plant food phytochemicals that are poorly absorbed by humans usually undergo metabolism and rapid excretion. It is clear from in vitro and animal data that the actions of some phytochemicals are likely to be achieved only at doses much higher than those present in edible plant foods. Thus, extraction or synthesis of the active ingredient is essential if they are to be of prophylactic or therapeutic value in human subjects.

Figure 2.1 Classification of phytochemicals.

Many phytochemicals have a range of different biochemical and physiological effects, isoflavonoids, for example have antioxidant and anti-oestrogenic activities. These activities may require different plasma or tissue concentrations for optimum effects. A diagram illustrating the classification of the phytochemicals covered in this chapter is shown in Figure 2.1.

In addition, plants contain mixtures of phytochemicals (Table 2.1), with considerable opportunity for interaction (Rowland et al., 1999). Plant secondary metabolites are an enormously variable group of phytochemicals in terms of their number, structural heterogeneity, and distribution.

A summary of the main groups of bioactive chemicals in edible plants, their sources, and their biological activities is presented in Table 2.2 (Rowland et al., 1999).

The term terpenes originates from turpentine (balsamum terebinthinae). Turpentine, the so-called “resin of pine trees”, is the viscous pleasantly smelling balsam that flows upon cutting or carving the bark and the new wood of several pine tree species (Pinaceae). Turpentine contains the “resin acids” and some hydrocarbons, which were originally referred to as terpenes. Traditionally, all natural compounds built up from isoprene subunits and, for the most part, originating from plants are denoted as terpenes (Breitmaier, 2006).

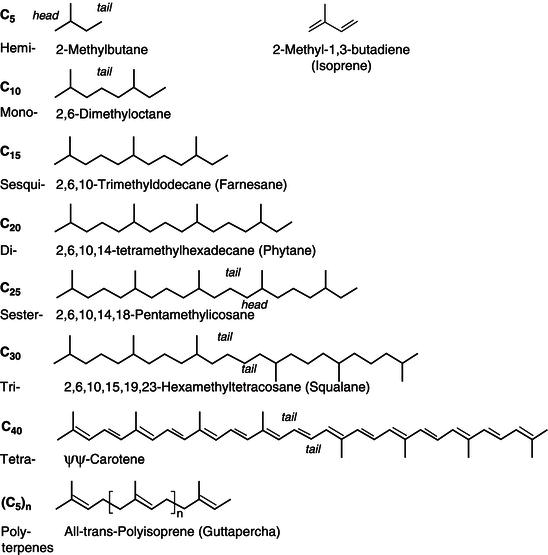

All living organisms manufacture terpenes for certain essential physiological functions and therefore have the potential to produce terpene natural products. Given the many ways in which the basic C5 units can be combined together and the different selection pressures under which organisms have evolved, it is not surprising to observe the enormous number and diversity of structures elaborated (Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007). Terpenes (also known as terpenoids or isoprenoids) are the largest group of natural products comprising approximately 36 000 terpene structures (Buckingham, 2007), but very few have been investigated from a functional perspective (Figure 2.2).

Table 2.1 Phytochemical content of some edible plants (modified from Caragay, 1992; Rowland et al., 1999)

Table 2.2 Sources and biological activities of phytochemicals (adapted from Rowland et al., 1999)

Figure 2.2 Examples of terpenes with established functions in nature (adapted from Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007).

The classification of terpenoids is based on the number of isoprenoid units present in their structure. The largest categories consist of compounds with two (monoterpenes), three (sesquiterpenes), four (diterpenes), five (sesterterpenes), six (triterpenes), and eight (tetraterpenes) isoprenoid units (see Figure 2.3) (Ashour et al., 2010).

Terpenoids have well-established roles in almost all basic plant processes, including growth, development, reproduction, and defence (Wink and van Wyk, 2008). Gibberellins, a large group of diterpene plant hormones involved in the control of seed germination, stem elongation, and flower induction (Thomas et al., 2005) are among the best-known lower (C5–C20) terpenes. Another terpenoid hormone, abscisic acid (ABA), is not properly considered a lower terpenoid, since it is formed from the oxidative cleavage of a C40 carotenoid precursor (Schwartz et al., 1997).

Figure 2.3 Parent hydrocarbons of terpenes (isoprenoids) (modified from Breitmaier, 2006).

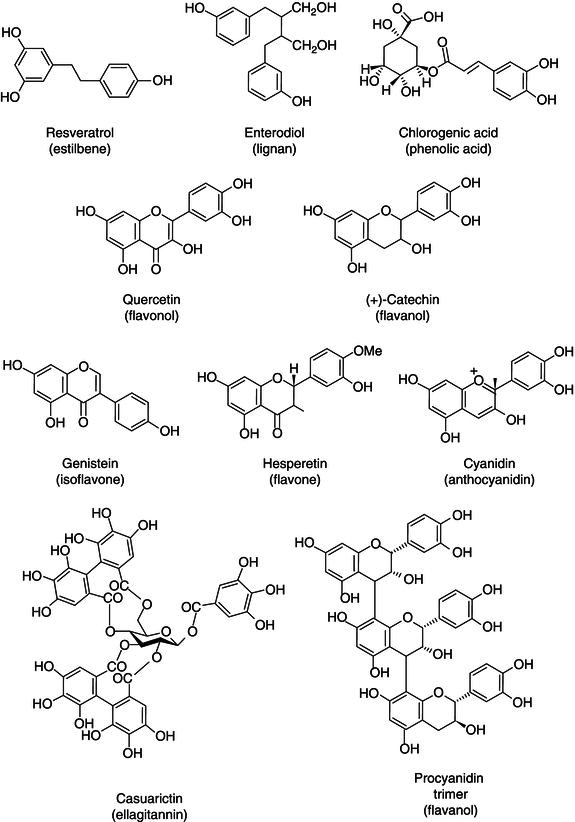

Polyphenols, secondary plant metabolites are the most abundant antioxidants in human diets. These compounds are designed with an aromatic ring carrying one or more hydroxyl moieties. Several classes can be considered according to the number of phenol rings and to the structural elements that bind these rings. In this context, two main groups of polyphenols, termed flavonoids and nonflavonoids, have been traditionally adopted. As seen in Figures 2.4 and 2.5, the flavonoid group comprises compounds with a C6-C3-C6 structure: flavanones, flavones, dihydroflavonols, flavonols, flavan-3-ols, anthocyanidins, isoflavones, and proanthocyanidins. The nonflavonoids group is classified according to the number of carbons and comprises the following subgroups: simple phenols, benzoic acids, hydrolyzable tannins, acetophenones and phenylacetic acids, cinnamic acids, coumarins, benzophenones, xanthones, stilbenes, chalcones, lignans, and secoiridoids (Andrés-Lacueva et al ., 2010).

Figure 2.4 Chemical structures of the main classes of polyphenols (adapted from Scalbert and Williamson, 2000).

Figure 2.5 Chemical structures of some representative flavonoids (adapted from Tapas et al., 2008).

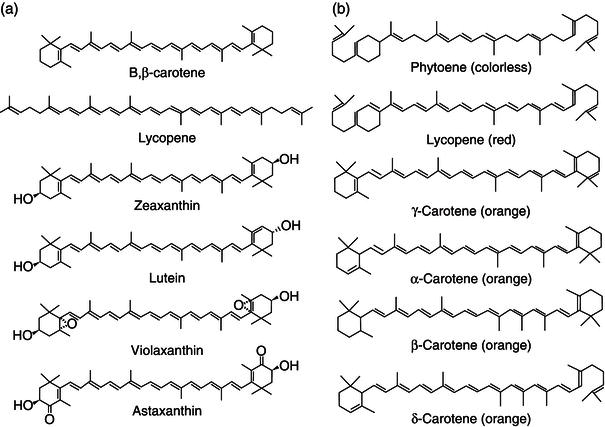

Carotenoids are fat-soluble natural pigments with antioxidant properties (Krinsky and Yeum, 2003), with various other additional physiological functions, such as immunostimulation (McGraw and Ardia, 2003). The more than 600 known carotenoids are generally classified as xanthophylls (containing oxygen) or carotenes (purely hydrocarbons with no oxygen). Carotenoids in general absorb blue light and serve two key roles in plants and algae: they absorb light energy for use in photosynthesis, and protect chlorophyll from photodamage (Armstrong and Hearst, 1996). In humans, four carotenoids ( α -, β -, and γ -carotene, and β -cryptoxanthin) have vitamin A activity (i.e. can be converted to retinal), and these and other carotenoids can also act as antioxidants (Figure 2.6). In the eye, certain other carotenoids (lutein and zeaxanthin) apparently act directly to absorb damaging blue and near-ultraviolet light, in order to protect the macula lutea. People consuming diets rich in carotenoids from natural foods, such as fruits and vegetables, are healthier and have lower mortality from a number of chronic illnesses (Diplock et al., 1998).

Glucosinolates (GLS), a group of plant thioglucosides found among several vegetables (Larsen, 1981), are a class of organic compounds containing sulfur and nitrogen and are derived from glucose and an amino acid (Anastas and Warner, 1998). Over 100 different GLS have been characterized since the first crystalline glucosinolate, sinalbin, was isolated from the seeds of white mustard in 1831. GLS occur mainly in the order Capparales, principally in the Cruciferae, Resedaceae, and Capparidaceae families, although their presence in other families has also been reported (Larsen, 1981). Some economically important GLS containing plants are white mustard, brown mustard, radish, horse radish, cress, kohlrabi, cabbages (red, white, and savoy), brussel sprouts, cauliflower, broccoli, kale, turnip, swede, and rapeseed (Fenwick et al., 1989).

Figure 2.6 Some examples of carotenoids ((a) adapted from Sliwka et al., 2010; (b) adapted from Yahia et al., 2010)).

GLS hydrolysis and metabolic products have proven chemoprotective properties against chemical carcinogens by blocking the initiation of tumours in various tissues, for example, liver, colon, mammary gland, and pancreas. They exhibit their effect by inducing Phase I and II enzymes, inhibiting the enzyme activation, modifying the steroid hormone metabolism and protecting against oxidative damage. GLS facilitate detoxificiation of carcinogens by inducing Phase I and Phase II enzymes. Some enzymes of Phase I reaction that activate the carcinogens, are selectively inhibited by glucosinolate metabolites (Das et al., 2000).

Dietary fiber is the edible parts or analogous carbohydrates resistant to digestion and absorption in the small intestine with complete or partial fermentation in the large intestine. Dietary fiber includes polysaccharides, oligosaccharides, lignin, and associated plant substances. Dietary fibers promote beneficial physiological effects including laxation, and/ or blood cholesterol attenuation, and/or blood glucose attenuation (AACC, 2001) (Table 2.3). Dietary fibers are polymers of monosaccharides joined through glycosidic linkages and are defined and classified in terms of the following structural considerations: (a) identity of the monosaccharides present; (b) monosaccharide ring forms (six-membered pyranose or five-membered furanose); (c) positions of the glycosidic linkages; (d) configurations (a or b) of the glycosidic linkages; (e) sequence of monosaccharide residues in the chain, and (f) presence or absence of non-carbohydrate substituents. Monosaccharides commonly present in cereal cell walls are: (a) hexoses – D-glucose, D-galactose, D-mannose; (b) pentoses – L-arabinose, D-xylose; and (c) acidic sugars – D-galacturonic acid, D-glucuronic acid and its 4-O-methyl ether (Choct, 1997).

Table 2.3 Constituents of dietary fiber according to the definition of the American Association of Cereal Chemists (adapted from Jones, 2000)

| Non starch polysaccharides (NSP) and resistant |

| Cellulose Hemicellulose Arabinoxylans Arabinogalactans Polyfructose Inulin Oligofructans Galacto-oligosaccharides Gums Mucilages Pectins Analogous carbohydrates Indigestible dextrins Resistant maltodextrins (from maize and others sources) Resistant potato dextrins Synthesized carbohydrate compounds Polydextrose Methyl cellulose Hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose Indigestible (“resistant”) starches Lignin substances associated with the NSP and lignin complex in Plants Waxes Phytate Cutin Saponins Suberin Tannins |

According to Cummings (1997), the health benefits of DF do not provide a distinct disease-related characteristic that can be exclusively associated with it. Constipation comes closest to fulfilling such a criterion and it is clear that some functional and physiological effects have been demonstrated with some specific fibers: (a) faecal bulking or stool output (ispaghula, xanthan gum, and wheat bran); (b) lowering of postprandial blood glucose response (highly viscous guar gum or β -glucans); (c) lowering of plasma (LDL-) cholesterol (highly viscous guar gum, β -glucans or oat bran, pectins, psyllium). Other effects have not yet been demonstrated in human subjects, such as colonic health effects related to fermentation products, although a substantial body of evidence is available from in vitro or animal models (Champ et al., 2003 and references therein).

Lectins (from lectus, the past participle of legere, to select or choose) are defined as carbohydrate binding proteins other than enzymes or antibodies and exist in most living organisms, ranging from viruses and bacteria to plants and animals. Some examples are given in Table 2.4. Their involvement in diverse biological processes in many species, such as clearance of glycoproteins from the circulatory system, adhesion of infectious agents to host cells, recruitment of leukocytes to inflammatory sites, cell interactions in the immune system, in malignancy and metastasis, has been shown (Ambrosi et al., 2005 and references therein).

Table 2.4 Examples of lectins, the families to which they belong and their glycan ligand specificities (modified from Ambrosi et al., 2005 and references therein)

| Lectin name | Family | Glycan ligands |

| Plant lectins | ||

| Concanavalin A (Con A; jack bean) | Leguminosae | Man/Glc |

| Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA; wheat) | Gramineae | (GlcNAc)1–3, Neu5Ac |

| Ricin (castor bean) | Euphorbiaceae | Gal |

| Phaseolus vulgaris (PHA; French bean) | Leguminosae | Unknown |

| Peanut agglutinin (PNA; peanut) | Leguminosae | Gal, Galb3GalNAca (T-antigen) |

| Soybean agglutinin (SBA; soybean) | Leguminosae | Gal/GalNAc |

| Pisum sativum (PSA; pea) | Leguminosae | Man/Glc |

| Lens culinaris (LCA; lentil) | Leguminosae | Man/Glc |

| Galanthus nivalus (GNA; snowdrop) | Amaryllidaceae | Man |

| Dolichos bifloris (DBA; horse gram) | Leguminosae | GalNAca3GalNAc, GalNAc |

| Solanum tuberosum (STA; potato) | Solanaceae | (GlcNAc)n |

The term “alkaloid” was coined by the German pharmacist Carl Friedrich Wilhelm Meissner in 1819 to refer to plant natural products (the only organic compounds known at that time) showing basic properties similar to those of the inorganic alkalis (Friedrich and Von, 1998) The ending “-oid” (from the Greek eidv, appear) is still used today to suggest similarity of structure or activity, as is evident in names of more modern vintage such as terpenoid, peptoid, or vanilloid (Hesse, 2002).

Among the secondary metabolites that are produced by plants, alkaloids figure as a very prominent class of defense compounds. Over 21 000 alkaloids have been identified, which thus constitute the largest group among the nitrogen-containing secondary metabolites (besides 700 nonprotein amino acids, 100 amines, 60 cyanogenic glycosides, 100 glucosinolates, and 150 alkylamides) (Roberts and Wink, 1998; Wink, 1993). An alkaloid never occurs alone; alkaloids are usually present as a mixture of a few major and several minor alkaloids of a particular biosynthetic unit, which differ in functional groups (Wink, 2005).

Polyacetylenes are examples of bioactive secondary metabolites that were previously considered undesirable in plant foods due to their toxicity (Czepa and Hofmann, 2004) (Figure 2.7). However, a low daily intake of these “toxins” may be an important factor in the search for an explanation of the beneficial effects of fruit and vegetables on human health. For example, polyacetylenes isolated from carrots have been found to be highly cytotoxic against numerous cancer cell lines. Over 1400 different polyacetylenes and related compounds have been isolated from higher plants.

Figure 2.7 Polyacetylenes structure (a) Falcarinol (FaOH), (b) Falcarindiol (FaDOH), (c) Falcarindiol 3-acetate (FaDOAc).

Aliphatic C17-polyacetylenes of the falcarinol type such as falcarinol and falcarindiol (Figure 2.7), are widely distributed in the Apiaceae and Araliaceae (Bohlmann et al., 1973; Hansen and Boll, 1986), and consequently nearly all polyacetylenes found in the utilized/edible parts of food plants of the Apiaceae, such as carrot, celeriac, parsnip, and parsley are of the falcarinol-type. Falcarinol, a polyacetylene with anti-cancer properties, is commonly found in the Apiaceae, Araliaceae, and Asteraceae plant families (Zidorn et al., 2005). Other polyacetylenes had been reported from other plants like Centella asiatica, Bidens pilosa (Cytopiloyne), Panax quinquefolium L. (American ginseng), and Dendranthema zawadskii (Dendrazawaynes A and B), among others.

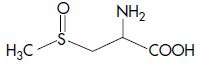

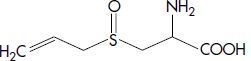

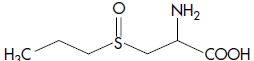

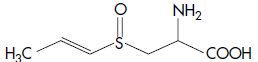

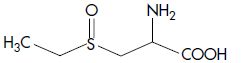

Early investigators identified volatile odour principles in garlic oils – however, these compounds were only generated during tissue damage and preparation. Indeed, the vegetative tissues of Allium species are usually odour-free, and it is this observation that led to the hypothesis that the generation of volatile compounds from Allium species arose from non-volatile precursor substances. It was in the laboratory of Stroll and Seebrook in 1948 that the first stable precursor compound, (+)-S-allyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide (ACSO), commonly known as alliin, was identified; it makes garlic unique sulfur-containing molecules among vegetables (Stoll and Seebeck, 1947). Alliin is the parental sulfur compound that is responsible for the majority of the odorous volatiles produced from crushed or cut garlic. Three additional sulfoxides present in the tissues of onions were later identified in the laboratory of Virtanen and Matikkala, these being (+)-S-methyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide (methiin; MCSO), (+)-S-propyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide (propiin; PCSO), and (+)-S-trans-1-propenyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide or isoalliin (TPCSO). Isoalliin is the major sulfoxide present within intact onion tissues and is the source of the A. cepa lachrymatory factor (Virtanen and Matikkala, 1959). With regards to chemical distribution, (+)-S-methyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide is by far the most ubiquitous, being found in varying amounts in the intact tissues of A. sativum, A. cepa, A. porrum, and A. ursinum L (Table 2.5).

Table 2.5 S-Alk(en)yl cysteine in Allium spp (modified from Rose et al., 2005)

| Common name | Chemical name | Chemical structure |

| Methiin | S-Methyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide |  |

| Aliin | S-Allyl-L.cysteine sulfoxide |  |

| Propiin | S -Propyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide |  |

| Isoalliin | S-Propenyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide |  |

| Ethiin | S -Ethyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide |  |

| Butiin | S-n-Butyl-L-cysteine sulfoxide |  |

Upon hydrolysis and oxidation, oil-soluble allyl compounds, which normally account for 0.2–0.5% of garlic extracts, such as diallyl sulfide (DAS), 5 diallyl disulfide (DADS), diallyl trisulfide (DATS), and other allyl polysulfides (2), are generated. Alternatively, it can be slowly converted into watersoluble allyl compounds, such as S-allyl-cysteine and S-allylmercaptocysteine (SAMC) (Filomeni et al., 2008 and references there in).

Chlorophyll (also chlorophyl) is a green pigment found in almost all plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. Its name is derived from the Greek words chloros (“green”) and phyllon (“leaf”). Chlorophyll is an extremely important biomolecule, critical in photosynthesis, which allows plants to obtain energy from light. Chlorophyll absorbs light most strongly in the blue portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, followed by the red portion. However, it is a poor absorber of green and near-green portions of the spectrum; hence the green color of chlorophyll-containing tissues (Speer, 1997). Chlorophyll was first isolated by Joseph Bienaimé Caventou and Pierre Joseph Pelletier in 1817 (Pelletier and Caventou, 1951).

In pepper, unripe fruit colors can vary from ivory, green, or yellow. The green color derives from accumulation of chlorophyll in the chloroplast while ivory indicates chlorophyll degradation as the fruit ripens (Wang et al., 2005). The persistent presence of chlorophyll in fruit ripening to accumulate other pigments like carotenoids or anthocyanins produces brown or black mature fruit colors. Chlorophyll in black pepper fruit is 14-fold higher compared to violet fruit (Lightbourn et al., 2008).

Figure 2.8 Capsaicin.

The name “betalain” comes from the Latin name of the common beet (Beta vulgaris), from which betalains were first extracted. The deep red color of beets, bougainvillea, amaranth, and many cacti results from the presence of pigments. Betalains are a class of red and yellow indole-derived pigments found in plants of the Caryophyllales, where they replace anthocyanin pigments, as well as some higher order fungi (Strack and Schliemann, 2003).

There are two categories of betalains: Betacyanins include the reddish to violet betalain pigments and betaxanthins that are those betalain pigments that appear yellow to orange. Among the betaxanthins present in plants include vulgaxanthin, miraxanthin and portulaxanthin, and indicaxanthin (Salisbury et al., 1991).

The few edible known sources of betalains are red and yellow beetroot (Beta vulgaris L. ssp. vulgaris), coloured Swiss chard (Beta vulgaris L. ssp. cicla), grain or leafy amaranth (Amaranthus sp.), and cactus fruits, such as those of Opuntia and Hylocereus genera (Azeredo, 2009 and references there in).

The nitrogenous compounds produced in pepper fruit, which cause a burning sensation, are called capsaicinoids. Capsaicinoids are purported to have antimicrobial effects for food preservation (Billing and Sherman, 1998), and their most medically relevant use is as an analgesic (Winter et al., 1995). Capsaicinoids have been used successfully to treat a wide range of painful conditions including arthritis, cluster headaches, and neuropathic pain. The analgesic action of the capsaicinoids has been described as dose dependent, and specific for polymodal nociceptors. The gene for the capsaicinoid receptor has been cloned (TRPV1) and the receptor transduces multiple pain-producing stimuli (Caterina et al., 1997; Tominaga et al., 1998). Capsaicin (trans-8-N-vamllyl-6-nonenamide) is an acrid, volatile alkaloid responsible for hotness in peppers (Figure 2.8).

The basic structure of terpenes follows a general principle: 2-Methylbutane residues, less precisely but usually also referred to as isoprene units, (C 5 ) n, build up the carbon skeleton of terpenes; this is the isoprene rule 1 formulated by Ruzicka (1953) (Figures 2.2 and 2.3). The isopropyl part of 2-methylbutane is defined as the head , and the ethyl residue as the tail (Breitmaier, 2006). In nature, terpenes occur predominantly as hydrocarbons, alcohols and their glycosides, ethers, aldehydes, ketones, carboxylic acids, and esters (Breitmaier, 2006).

Several important groups of plant compounds, including cytokinins, chlorophylls, and the quinone-based electron carriers (the plastoquinones and ubiquinones), have terpenoid side chains attached to a non-terpenoid nucleus. These side chains facilitate anchoring to or movement within membranes. In plants, prenylated proteins may be involved in the control of the cell cycle (Qian et al., 1996; Crowell, 2000), nutrient allocation (Zhou et al., 1997), and abscisic acid signal transduction (Clark et al., 2001).

The most abundant hydrocarbon emitted by plants is the hemiterpene (C5) isoprene, 2-methyl-1,3-butadiene. Emitted from many taxa, especially woody species, isoprene has a major impact on the redox balance of the atmosphere, affecting ozone, carbon monoxide, and methane levels (Lerdau et al., 1997). The release of isoprene from plants is strongly influenced by light and temperature, with the greatest release rates typically occurring under conditions of high light and high temperature (Lichtenthaler, 2007). Although the direct function of isoprene in plants themselves has been a mystery for many years, there are now indications that it may serve to prevent cellular damage at high temperatures, perhaps by reacting with free radicals to stabilize membrane components (Sasaki et al., 2007).

Simple phenols (C6), the simplest group, are formed with an aromatic ring substituted by an alcohol in one or more positions as they may have some substituent groups, such as alcoholic chains, in their structure (Andrés-Lacueva et al., 2010). Phenolic acids (C6<-C1) with the same structure as simple phenols are hydroxylated derivatives of benzoic and cinnamic acids (Herrmann, 1989; Shahidi and Naczk, 1995). They act as cell wall support materials (Wallace and Fry, 1994) and as colourful attractants for birds and insects helping seed dispersal and pollination (Harborne, 1994). Hydrolyzable tannins are mainly glucose esters of gallic acid. Two types are known: the gallotannins, which yield only gallic acid upon hydrolysis, and the ellagitannins, which produce ellagic acid as the common degradation product (see Figure 2.4) (Andrés-Lacueva et al., 2010).

Acetophenones are aromatic ketones, and phenylacetic acids have a chain of acetic acid linked to benzene. Both have a C6-C2 structure. Hydroxycinnamic acids are included in the phenylpropanoid group (C6-C3). They are formed with an aromatic ring and a three-carbon chain. There are four basic structures: the coumaric, caffeic, ferulic, and sinapic acids. In nature, they are usually associated with other compounds such as chlorogenic acid, which is the link between caffeic and quinic acids (Andrés-Lacueva et al., 2010). Coumarins belong to the benzopyrone group of compounds, all of which consist of a benzene ring joined to a pyrone. They may also be found in nature, in combination with sugars, as glycosides. They can be categorized as simple furanocoumarins, pyranocoumarins, and coumarins substituted in the pyrone ring (Murray et al., 1982). Benzophenones and xanthones have the C6-C1-C6 structure. The basic structure of benzophenone is a diphenyl ketone, and that of xanthone is a 10-oxy-10 H-9- oxaanthracene. More than 500 xanthones are currently known to exist in nature, and approximately 50 of them are found in the mangosteen with prenyl substituents (Andrés-Lacueva et al., 2010). Stilbenes have a 1,2-diphenylethylene as their basic structure (C6-C2-C6). Resveratrol, the most widely known compound, contains three hydroxyl groups in the basic structure and is called 3,4,5-trihydroxystilbene. Stilbenes are present in plants as cis or trans isomers. Trans forms can be isomerized to cis forms by UV radiation (Lamuela-Raventós et al., 1994). Lignans in the strict sense are phenylpropanoid dimers linked by a C-C bond between carbons 8 and 8 ‘ prime’ in the side chain; they can be divided into several subgroups, depending on other linkages and substitution patterns introduced into the original hydroxycinnamyl alcohol dimmer. More than 55 plant families contain lignans, mainly gymnosperms and dicotyledonous angiosperms (Dewick, 1989).

Flavonoids constitute one of the most ubiquitous groups of all plant phenolics. So far, over 8000 varieties of flavonoids have been identified (De Groot and Raven, 1998). In plants, flavonoids are usually glycosylated mainly with glucose or rhamnose, but they can also be linked with galactose, arabinose, xylose, glucuronic acid, or other sugars (Vallejo et al., 2004). All flavonoids contain 15 carbon atoms in their basic nucleus: two six-membered rings linked with a three-carbon unit, which may or may not be parts of a third ring (Middleton, 1984). The rings are labeled A, B, and C (see Figure 2.5). The individual carbon atoms are based on a numbering system that uses ordinary numerals for the A and C and “primed” numerals for B-ring (1). Primed modified numbering system is not used for chalcones (2) and the isoflavones derivatives (6): the pterocarpans and the rotenoids. The different ways to close this ring associated with the different oxidation degrees of ring A provide the various classes of flavonoids. The six-membered ring condensed with the benzene ring is either a α -pyrone (flavones (1) flavonols (3) or its dihydroderivative (flavanones (4) and flavan-3-ols (5)). The position of the benzenoid substituent divides the flavonoids into two classes: flavonoids (1) (2-position) and isoflavonoids (6) (3-position). Most flavonoids occur naturally associated with sugar in conjugated form and, within any one class, may be characterized as monoglycosidic, diglycosidic, etc. The glycosidic linkage is normally located at position 3 or 7 and the carbohydrate unit can be L-rhamnose, D-glucose, glucorhamnose, galactose, or arabinose (Tapas et al., 2008 and references therein).

Carotenoids consist of 40 carbon atoms (tetraterpenes) with conjugated double bonds. They consist of eight isoprenoid units joined in such a manner that the arrangement of isoprenoid units is reversed at the center of the molecule so that the two central methyl groups are in a 1,6-position and the remaining nonterminal methyl groups are in a 1,5-position relationship. They can be acyclic or cyclic (mono- or bi-, alicyclic or aryl) (see Figure 2.6) (Yahia and Ornelas-Paz, 2010).

Carotenoids are often used in visual displays through deposition in skin or feathers. Given these multiple uses that all require substantial amounts of carotenoids for normal functioning, carotenoids have been suggested to be in limited supply for reproduction, health related functions, or the expression of sexual coloration. For example, it has been suggested that carotenoids may limit vital functions, such as scavenging of free radicals, eliminating peroxides, and enhancing immune function (production of lymphocytes, enhancement of phagocytic ability of neutrophils and macrophages, production of tumor immunity), in which they have been shown to be involved (Møller et al., 2000).

In nature, carotenoids exist as only two varieties: (1) unelaborated hydrocarbons, or (2) with functional groups, these are always attached via oxygen to the carotenoid skeleton. Carotenoids with heteroatoms other than oxygen have not yet been discovered in nature, but have been synthesized (Pfander, 1976). Hydrocarbon carotenoids generally form colored monomolecular solutions in nonpolar organic solvents, whereas and typically remain colorless in water. At extremely low carotenoid concentration, water unexpectedly exhibits an orange tint (the highly unsaturated polyene chain acting as a hydrophilic component). Strangely enough, the first carotenoid aggregates in water were obtained from β , β -carotene (von Euler et al., 1931). Its well-known hydrophobicity did not prevent other studies with β , β -carotene, and lycopene, an acyclic carotenoid hydrocarbon (Song and Moore, 1974; Bystritskaya and Karpukhin, 1975; Mortensen et al., 1997; Lindig and Rodgers, 1981). The many natural carotenols and carotenones (zeaxanthin, lutein, violoxanthin, astaxanthin) are undoubtedly more suited for aggregation studies in water (Mori, 2001; Zsila et al., 2001; Billsten et al., 2005; Köpsel et al., 2005).

The overwhelming majority of the ~750 known naturally occurring carotenoids are hydrophobic (Britton et al., 2004). It is therefore a striking paradox that the most utilized carotenoid since antiquity is extremely water-soluble: crocin has no saturation point in water. Crocin illustrates the typical surfactant structure, the hydrophobic polyene chain linked to two hydrophilic sugars; it is surface active, and the molecules associate to small oligomers at high concentration. The surface and aggregation properties of crocin have only recently been determined (Nalum-Naess et al., 2006). Meanwhile, other natural sugar carotenoids have been isolated and characterized, however, the low occurrence and abundance of these “red sugar derivatives” prevents practical applications (Dembitsky, 2005). Another group of naturally occurring carotenoids – sulfates – are considerably less hydrophilic; the first characterized compound was bastaxanthin sulphate (Hertzberg et al., 1983). A proposed application of carotenoid sulfates as feed/flesh colorants for cultured fish requires the additional help of an organic solvent for good outcomes (Yokyoyama and Shizusato, 1997). The “strange” appearance of the first recorded carotenoid sulfate visible spectrum in water was not immediately recognized as a sign of H-aggregation (Hertzberg and Liaaen-Jensen, 1985). The aggregation of a carotenoid sulfate was later observed as a negative outcome (Oliveros et al., 1994). Norbixin is the other carotenoid utilized since ancient times; it is reported to be water-soluble up to 5%. Recent measurements could not confirm solubility; only negligible dispersibility was observed (Breukers et al., 2009).

In the modern age, in addition to crocin and norbixin, several carotenoids have become extremely important commercially. These include, in particular, astaxanthin (fish, swine, and poultry feed, and recently human nutritional supplements); lutein and zeaxanthin (animal feed and poultry egg production, human nutritional supplements); and lycopene (human nutritional supplements). The inherent lipophilicity of these compounds has limited their potential applications as hydrophilic additives without significant formulation efforts; in the diet, the lipid content of the meal increases the absorption of these nutrients, however, parenteral administration to potentially effective therapeutic levels requires separate formulation that is sometimes ineffective or toxic (Lockwood et al., 2003).

Glucosinolates are amino acid-derived secondary plant metabolites found exclusively in cruciferous plants. The majority of cultivated plants that contain glucosinolates belong to the family of Brassicaceae such as brussel sprouts, cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower. These are the major source of glucosinolates in the human diet – about 120 different glucosinolates have been characterized. Glucosinolates and their breakdown products are of particular interest because of their nutritive and antinutritional properties, their potential adverse effects on health, their anticarcinogenic properties, and finally the characteristic flavour and odour they give to many vegetables (Verkerk and Dekker, 2008).

The majority of cultivated plants that contain glucosinolates belong to the family of Brassicaceae. Mustard seed, used as a seasoning, is derived from B. nigra, B. juncea (L.) Coss, and B. hirta species. Vegetable crops include cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, brussel sprouts, and turnip of the B. oleracea L., B. rapa L., B. campestris L., and B. napus L. species. Kale of the B. oleracea species is used for forage, pasture, and silage. Brassica vegetables such as brussel sprouts, cabbage, broccoli, and cauliflower are the major source of glucosinolates in the human diet. They are frequently consumed by humans from Western and Eastern cultures (McNaughton and Marks, 2003). In the Netherlands, the average consumption of these vegetables is more than 36 g Brassica per person per day (Godeschalk, 1987). The typical flavor of Brassica vegetables is largely due to glucosinolate-derived volatiles. The versatility of these compounds is also demonstrated by the fact that glucosinolates are quite toxic to some insects and therefore could be included as one of many natural pesticides. However, a small number of insects, such as the cabbage aphids, use glucosinolates to locate their favorite plants as feed and to find a suitable environment to deposit their eggs (Barker et al., 2006). Furthermore, glucosinolates show antifungal and antibacterial properties (Fahey et al., 2001).

Table 2.6 Glucosinolates commonly found in Brassicca vegetables (adapted from Verkerk and Dekker, 2008)

| Trivial name | Chemical name (side chain R) |

| Aliphatic glucosinolates | |

| Glucoiberin | 3-Methylsulfinylpropyl |

| Progoitrin | 2-Hydroxy-3-butenyl |

| Sinigrin | 2-Propenyl |

| Gluconapoleiferin | 2-Hydroxy-4-pentenyl |

| Glucoraphanin | 4-Methylsulfinylbutyl |

| Glucoalyssin | 5-Methylsulfinylpentyl |

| Glucocapparin | Methyl |

| Glucobrassicanapin | 4-Pentenyl |

| Glucocheirolin | 3-Methylsulfonylpropyl |

| Glucoiberverin | 3-Methylthiopropyl |

| Gluconapin | 3-Butenyl |

| Indole glucosinolates | |

| 4-Hydroxyglucobrassicin | 4-Hydroxy-3-indolylmethyl |

| Glucobrassicin | 3-Indolylmethyl |

| 4-Methoxyglucobrassicin | 4-Methoxy-3-indolylmethyl |

| Neoglucobrassicin | 1-Methoxy-3-indolylmethyl |

| Aromatic glucosinolates | |

| Glucosinalbin | p-Hydroxybenzyl |

| Glucotropaeolin | Benzyl |

| Gluconasturtiin | 2-Phenethyl |

Only a limited number of glucosinolates have been investigated thoroughly although there are about 120 different ones currently characterized. A considerable amount of data on levels of total and individual glucosinolates are now available. The levels of total glucosinolates in plants may depend on variety, cultivation conditions, climate, and agronomic practice, while the levels within a particular plant vary between the parts of the plant. Generally the same glucosinolates occur in a particular sub-species regardless of genetic origin, and in most species only between one and four glucosinolates are found in relatively high concentrations (Table 2.6). Glucosinolates are chemically stable and biologically inactive when separated within sub-cellular compartments throughout the plant. However, tissue damage caused by pests, harvesting, food processing, or chewing initiates contact with the endogenous enzyme myrosinase in the presence of water leading to hydrolysis releasing a broad range of biologically active products such as isothiocyanates (ITCs), organic cyanides, oxazolidinethiones, and ionic thiocyanate.

Glucosinolate breakdown products exert a variety of toxic and antinutritional effects in higher animals amongst which the adverse effects on thyroid metabolism are the most thoroughly studied (Tripathi and Mishra, 2007). Tiedink et al. (1990, 1991) investigated the role of indole compounds and glucosinolates in the formation of N-nitroso compounds in vegetables. These studies revealed that the indole compounds present in Brassica vegetables can be nitrosated and thereby become mutagenic. However, the nitrosated products are stable only in the presence of large amounts of free nitrite.

Polysaccharides are widespread biopolymers, which quantitatively represent the most important group of nutrients in botanical feed. Carbohydrates constitute a diverse nutrient category ranging from sugars easily digested by monogastric animals in the small intestine to dietary fiber fermented by microbes in the large intestine.

The structure of the plant cell wall influences the physical and chemical properties of the individual NSP and these vary considerably between different polymers and different molecular weights of the same polymer (Choct, 1997). Another factor that differentiates the physical properties among polysaccharides is the way the monomer units of polysaccha rides are linked together (Moms, 1992). Different sugars linked together in the same way often give polysaccharides with very similar physical properties.

On the other hand, despite being built up from the same monomer units, polysaccharides can have different physical properties when the monomer units are linked together in different ways. The physiological effects of NSP on digestion and absorption of nutrients in human and monogastric animals have been attributed to its physicochemical properties. The main physicochemical properties of NSP that are of nutritional significance include: (a) hydration; (b) viscosity; (c) cation exchange capacity; and (d) organic compound absorptive properties. The hydration properties of NSP influence its water holding and binding capacity (Bach Knudsen, 2001). These depend on the physicochemical structure of the molecule and its ability to incorporate water within the molecular matrix. The viscosity properties of the NSP depend on its molecular weight or size (linear or branched), ionically charged groups, the surrounding structures, and the concentration of NSP (Smits and Annison, 1996). The cation exchange capacity is formed because the three-dimensional structure of the NSP molecule allows a chelation of ions to occur. The organic compound absorptive properties of NSP are due to its capacity to bind small molecules by both hydrophobic and hydrophilic bond interactions.

Although it seems apparent now that Weir Mitchell had already observed lectin activity in rattle snake venom before (Kilpatrick, 2002) it wasn’t until at least six years later, when Stillmark reported the dramatic action of ricin on red blood cells and then Helin followed it up by a similar report on abrin, that agglutinins caught the attention of the medical community. Reports of hemagglutinins from various sources were quick to follow. Besides plants, agglutinins were discovered in fungi, bacteria, viruses, invertebrates, and vertebrates. Although this early period established, beyond any doubt, the proteinaceous nature of lectins and their cell-agglutination and precipitation capabilities, lectin research thereafter was beset with problems and difficulties for the next quarter of a century. Studies, by Sugishita, Jonsson, Boyd, and Renkonen, provided the proverbial “shot in the arm” for research on lectins by identifying lectins as cell-recognition molecules that could have practical applications (Kocoureck, 1986). Reports of blood-group specificity, mitogenicity, and tumor cell-binding of lectins followed almost immediately.

The number of known properties and possible applications of lectins grew rapidly. Concanavalin A (Con A), a lectin from jack beans, became the first lectin to be crystallized and then extensively characterized by Sumner and Howell (1936) who also showed for the first time that sucrose could inhibit its agglutination activity. Two other major discoveries set the tone of the research that was to follow. Funatsu and his collaborators isolated the first non-toxic lectin from Ricinus communis , shattering the prevalent notion at that time that lectins were necessarily toxic proteins (Ishiguro et al ., 1964). Secondly, it was shown that several of these lectins, such as that from soybean, were glycoproteins (Lis and Sharon, 1973).

On the other hand, the effect of plant lectins on different cell types had already set the agenda for early research on them, leading to an extensive search for lectins in plant extracts and identification of a large number of lectins with practical applications. Such an objective did not require identification of the biological function of the protein per se . Indeed, in several cases where biological functions have been hypothesized or proven, the effect of the plant lectins on microbial or animal cells has provided clues to their putative function in vivo . Research on the endogenous roles of plant lectins has therefore been a late starter, although some progress has been made in this direction. Despite this, interest in studying plant lectins has been sustained, owing to the fact that their natural abundance makes their applications in a large number of areas much more feasible (Komath et al ., 2006 and references therein).

Glycosylation is the key step in a number of processes at the cellular level. Cell-surface oligosaccharides get altered in various kinds of pathological conditions including malignant transformations. With developments in the closely-related field of glycobiology, it has now become evident that oligosaccharide-mediated recognition plays a very important role in various biological processes such as fertilization, immune defence, viral replication, parasitic infection, cell–matrix interaction, cell–cell adhesion, and enzymatic activity. Lectins have been implicated in most, if not all of these recognition events. The strict selectivity that this kind of recognition requires imposes a stringent geometry upon both the ligand and the corresponding receptor, thus conferring unique sugar-specificities upon lectins (Sharon and Lis, 2004).

Carbohydrates can interact with lectins via hydrogen bonds, metal coordination bonds and van der Waal interaction and hydrophobic interaction. Selectivity results from specific hydrogen bonding and/or metal coordination bonds with key hydroxyls of the carbohydrates, which can act as both acceptors and donors of hydrogen bonds. Water molecules often act as bridges in these interactions. The hydroxyl at the C4 position, in particular, seems to be a decisive player in these events. Steric exclusions minimize unwanted recognition, further fine-tuning the saccharide specificity of the lectin. Subsite binding and subunit multivalency, where possible, increase the binding selectivity manifold (Rinni, 1995). In subsite binding, the primary binding site appears critical for carbohydrate recognition, but secondary binding sites contribute to enhanced affinity of the lectin towards specific oligosaccharides. For example, the legume lectins Lathyrus ochrus isolectin II (LOL II) and Con A are both Man/Glc specific lectins, but their oligosaccharide preferences are very different. LOL II has several-fold higher affinity for oligosaccharides that have additional a (1–6)-linked fucose residues, while Con A does not (Rinni, 1995; Weis and Drickamer, 1996). In subunit multivalency, several subunits of the same lectin contribute to the binding by recognizing different extensions of the carbohydrate or different chains of a branched oligosaccharide. This kind of binding is exhibited, among others, by the asialoglycoprotein receptor, the mannose binding protein (MBP) from the serum, the chicken hepatic lectin, and the cholera toxin (Drickamer, 1997; Elgavish and Shaanan, 1997). It appears that the monosaccharide specificity of a lectin, although useful, need not necessarily tell the complete story. It has become evident in numerous cases, particularly of lectins with proven or putative biological functions, that multivalency of the receptor is a prerequisite for recognition. Thus, the MBP, for example, binds to monomeric mannose units and simply releases them but, when it binds to the oligomannosides on a pathogen that has the same spacing as the trimers of MBP, it triggers a biological response that results in complement fixation (Komath et al., 2006 and references therein).

Plant alkaloids are important privileged compounds with many pharmacological activities (Beghyn et al., 2008; Facchini and Luca, 2008). In fact, alkaloid-containing plants have been recognized and exploited since ancient human civilization, from the utilization of Conium maculatum (hemlock) extract containing neurotoxin alkaloids to poison Socrates, to the use of coffee and tea as mild stimulants (Kutchan, 1995). Today, numerous alkaloids are pharmacologically well characterized and are used as clinical drugs, ranging from cancer chemotherapeutics to analgesic agents (Table 2.7).

Table 2.7 Alakloids with pharmaceutical applications (adapted from Leonard et al., 2009)

| Alkaloid | Plant species |

| Ajmaline | Rauwolfia sellowii |

| Berberine | Berberis vulgaris |

| Caffeine | Cofee arabica |

| Camptothecin | Camptotheca acuminata |

| Cocaine | Erythroxylon coca |

| Codeine | Papaver somniferum |

| Hyoscyamine | Hyoscyamus muticus |

| Irinotecan | – |

| Morphine | Papaver somniverum |

| Nicotine | Nicotiana tabacum |

| Noscapine | Papaver somniverum |

| Oxycodone | – |

| Oxymorphone | – |

| Papaverine | Papaver somniverum |

| Quinidine | Cinchona ledgeriana |

| Quinine | Cinchona ledgeriana |

| Reserpine | Rauwolfia nitida |

| Sanguinarine | Sanguinaria canadiensis |

| Scopolamine | Hyoscyamus muticus |

| Strychnine | Strychnos nux-vomica |

| Topotecan | – |

| Vinblastine | Catharanthus roseus |

| Vincristine | Catharanthus roseus |

| Vindesine | – |

| Vinflunine | – |

| Vinorelbine | – |

| Yohimbine | Pausinystalia yohimbe |

The clinical value of vinca alkaloids, for example, isolated from the Madagascar periwinkle, Catharantus roseus G. Don., was clearly identified as early as 1965 and so this class of compounds has been used as anti-cancer agents for over 40 years and represents a true lead compound for drug development (Sipiora et al., 2000).

A number of other alkaloids are known to have a bitter taste, and the response of cultured rat trigeminal ganglion neurons to bitter tastants has been studied (Liu and Simon, 1998). The authors investigated the responses of rat chorda tympani and glossopharnygeal neurons to a variety of bitter-tasting alkaloids. Of the 89 neurons tested, 34% responded to 1mM nicotine, 7% to 1mM caffeine, 5% to 1mM denatonium benzoate, 22% to 1mM quinine hydrochloride, 18% to 1mM strychnine, and 55% to 1mM capsaicin. These data suggest that neurons from the trigeminal ganglion respond to the same bitter-tasting chemical stimuli as do taste receptor cells and are likely to contribute information sent to the higher central nervous system regarding the perception of bitter/irritating chemical stimuli.

Many alkaloids mimicking the structures of monosaccha rides or oligosaccharides have been isolated from plants and microorganisms. Such alkaloids are easily soluble in water because of their polyhydroxylated structures and inhibit glycosidases because of a structural resemblance to the sugar moiety of the natural substrate. Glycosidases are involved in a wide range of important biological processes, such as intestinal digestion, post-translational processing of the sugar chain of glycoproteins , quality-control systems in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and ER associated degradation mechanism, and the lysosomal catabolism of glycoconjugates. Inhibition of these glycosidases can have profound effects on carbohydrate catabolism in the intestines, on the maturation, transport, and secretion of glycoproteins, and can alter cell–cell or cell–virus recognition processes. The realization that glycosidase inhibitors have enormous therapeutic potential in many diseases such as diabetes, viral infection, and lysosomal storage disorders has led to increasing interest in and demand for them (Asako, 2008). Acarbose, a potent inhibitor of intestinal sucrase, was effective in carbohydrate loading tests in rats and healthy volunteers, reducing postprandial blood glucose and increasing insulin secretion (Puls et al ., 1977).

A possible way to suppress hepatic glucose production and lower blood glucose in type 2 diabetes patients may be through inhibition of hepatic glycogen phosphorylase. Fosgerau et al. (2000) reported that in enzyme assays 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-d-arabinitol (DAB, alkaloid isolated from the leaves of Morus bombycis in Japan) is a potent inhibitor of hepatic glycogen phosphorylase. Furthermore, in primary rat hepatocytes, DAB was shown to be the most potent inhibitor of basal and glucagon-stimulated glycogenolysis ever reported (Andersen et al., 1999).

Acetylenic natural products include all compounds with a carbon-carbon triple bond or alkynyl functional group. While not always technically accurate, the term “polyacetylenes” is often used interchangeably to describe this class of natural products, although they are not polymers and many precursors and metabolites contain only a single acetylenic bond. These compounds tend to be unstable, succumbing either to oxidative, photolytic, or pH-dependent decomposition, which originally provided substantial challenges for their isolation and characterization (Minto and Blacklock, 2008). The earliest isolated alkyne-bearing natural product was dehydromatricaria ester, which was isolated, but not fully characterized, in 1826. No compound was characterized as being acetylenic until 1892 (tariric acid, 5 T) (Arnaud,1892, 1902), after which only a handful of compounds were isolated before 1952. A lecture by N. A. Sörensen to the Royal Chemical Society in Glasgow describes the early history of polyacetylenic natural product chemistry (Sörensen, 1961).

A diacetylenic 1,6-dioxaspiro[4.5]decane gymnasterkoreayne G (23A) was isolated from the aerial parts of Matricaria aurea (Asteraceae) and, along with four known gymn asterkoreaynes, was active in a transcription factor inhibitory screen of gymnasterkoraien sis leaf extract. Elevated levels of the NFAT transcription factor have been linked to auto-immune responses and inflammation. While 23B showed lower NFAT inhibition than the threo-diol-containing gymnasterkoreayne E (23 C), the differential activities of 23B, 23 C, and the epoxydiyne gymnasterkoreayne B (23D) illuminate the importance of the stereochemical arrangement of the oxygen functionalities in maximizing this inhibitory effect. Several of the gymnasterkoreaynes A-F exhibit anti-cancer activity. The gymnasterkoreaynes are found with polyacetylenes 23 F and 23E, the latter being their likely direct precursor. Three new diacetylenic spiroketals (23 G–I) were isolated from Plagius flosculosus and examined for cytotoxicity. They were found to be less active against Jurat T and HL-60 leukemia cells than known compounds that contained two unsaturated rings. Reduced sensitivity of Bcl-2-overexpressing cells to these natural products suggested a mechanism of action involving the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (Minto and Blacklock, 2008 and references therein).

Cytopiloyne, was identified from the Bidens pilosa extract using ex vivo T cell differentia tion assays based on a bioactivity-guided fractionation and isolation procedure. Its structure was elucidated as 2 β -d-glucopyranosyloxy-1-hydroxytrideca-5,7,9,11-tetrayne by various spectroscopic methods. Functional studies showed that cytopiloyne was able to inhibit the differentiation of naïve T helper (Th0) cells into type I T helper (Th1) cells but to promote the differentiation of Th0 cells into type II T helper (Th2) cell (Chiang et al., 2007). It has also been demonstrated that polyacetylene aglycones of B. pilosa, namely 1,2-dihydroxy tri deca- 5,7,9,11-tetrayne and 1,3- dihydroxy-6(E)-tetradecene-8,10,12-triyne, exhibit significant and potent anti-angiogenic activities. The ability of both compounds to block angiogenesis is possibly in part through induction of p27(Kip1) and regulation of other cell cycle mediators including p21(Cip1) and cyclin E (Wu et al., 2004).

Slight variations in polyacetylene structure result in extreme variations in biological activities. Low toxicity cicutol (46A), 4B, and 4 C can be contrasted with lethal K + -current blocker cicutoxin from water hemlock (46B) (Straub et al., 1996). The toxicity of 46B was found to have three structural requirements: an allylic alcohol, a long-conjugated (E)-polyene, and a terminal hydroxy group (Uwai et al., 2000).

The ACSOs are found in the cytoplasm of onion cells, physically separated from alliinase. When the tissues of any allium are disrupted, the enzyme alliinase hydrolyses the flavor precursors. The result is a wide range of reactive organosulphur compounds with characteristic flavor and striking bioactivity. The first products of the reaction between alliinase and the flavor precursors are the highly reactive sulphenic acids. In garlic, the 2-propene sulphenic acid condenses to form the thiosulphinate allicin (allyl-2- propenethiosulphinate), which gives it its characteristic flavor. In aged extracts of garlic, allicin can disproportionate (react with itself) to form the sulphides, thiosulphonates, and the trisulphur compound called ajoene. Ajoene has notable antithrombitic activity (Randle and Lancaster, 2002).

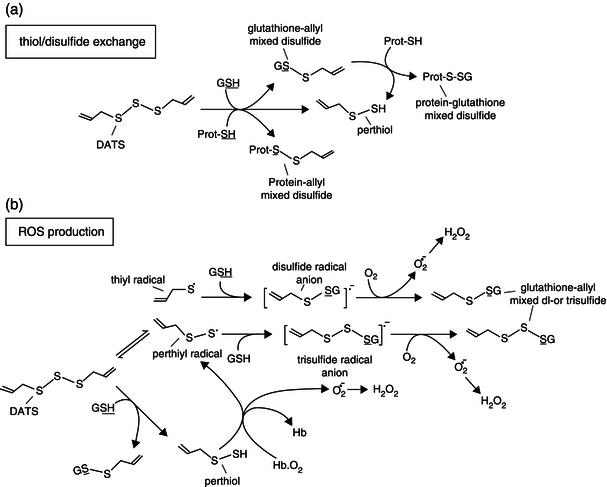

Figure 2.9 Redox chemistry of allyl sulfides Reproduced from (Filomeni et al., 2008), with permission from the American Society for Nutrition.

The chemical structure and reactivity of allyl compounds rather favor a pro-oxidant activity. In fact, oil-soluble allyl compounds are the main source of disulfides and polysulfides and, due to the high intracellular abundance of reduced glutathione (GSH) and protein thiols, they can mediate thiol/disulfide exchange by determining decrease of GSH and thiolation of reactive cysteine residues on proteins (Figure 2.9(a)). Whereas the former reaction induces oxidative unbalance, the latter yields reversible alterations of protein function, as demonstrated for the nonselective cation channel transient receptor potential-A1 of sensory nerve endings upon treatment with DADS, which underlies its pungent effects. Allyl disulfides and polysulfides can also produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) directly by reactions relying upon the homolytic cleavage of disulfide bond. This leads to the formation of allyl-(per)thiyl radicals, which can rapidly react with GSH, thus forming disulfide or polysulfide radical anions and reducing oxygen to produce ROS. Superoxide and hydrogen peroxide can be produced also as by-products of the reaction between perthiol and oxygen (e.g. O2 bound to hemoglobin; Figure 2.9(b)) (Filomeni et al., 2008).

Chlorophyll is a chlorin pigment, which is structurally similar to and produced through the same metabolic pathway as other porphyrin pigments such as heme. At the center of the chlorin ring is a magnesium ion. For the structures depicted in this chapter, some of the ligands attached to the Mg 2+ center are omitted for clarity. The chlorin ring can have several different side chains, usually including a long phytol chain. There are a few different forms that occur naturally, but the most widely distributed form in terrestrial plants is chlorophyll a (Figure 2.10). The general structure of chlorophyll a was elucidated by Hans Fischer in 1940, and by 1960, when most of the stereochemistry of chlorophyll a was known, Robert Burns Woodward published a total synthesis of the molecule as then known (Woodward et al ., 1960). In 1967, the last remaining stereochemical elucidation was completed by Ian Fleming (Fleming, 1967) and in 1990 Woodward and co-authors published an updated synthesis (Woodward et al ., 1990).

Figure 2.10 Chlorophyll structure.

Betalains are water-soluble nitrogen-containing pigments, which are synthesized from the amino acid tyrosine into two structural groups: the red-violet betacyanins and the yellow-orange betaxanthins. Betalamic acid, presented in Figure 2.11(a), is the chromophore common to all betalain pigments. The nature of the betalamic acid addition residue determines the pigment classification as betacyanin or betaxanthin (Figures 2.11(b) and 2.11(c)), respectively (Azeredo, 2009). They are not related chemically to the anthocyanins and are not even flavonoids (Raven et al., 2004). Each betalain is a glycoside, and consists of a sugar and a colored portion. Their synthesis is promoted by light (Salisbury and Cleon, 1991).

Figure 2.11 General structures of betalamic acid (a), betacyanins (b), and betaxanthins (c). Betanin: R1 = R2 = H. R3 = amine or amino acid group (Strack et al., 2003).

In natural plant, betalains play important roles in physiology, optical attraction for pollination, and seed dispersal (Piattelli, 1981). They also function as reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavengers, protect plants from damages caused by wounding and bacterial infiltration as seen in red beet (Beta vulgaris subsp. vulgaris) (Sepúlveda-Jiménez et al., 2004), and function as UV-protecter in ice plant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum) (Vogt et al., 1999).

Capsaicinoids all share a common aromatic moiety, the vanillylamine, and differ in the length and degree of unsaturation of the fatty acid side chain (Bennett and Kirby, 1968; Leete and Louden, 1968). The perception of burn from these individual capsaicinoids will also vary slightly; capsaicin (Figure 2.9) and dihydrocapsaicin are the hottest and deliver their bite everywhere from the mid-tongue and palate to down in the throat (Krajewska and Powers, 1998).

Capsaicinoids start to accumulate 20 days post anthesis and synthesis usually persists through fruit development. The site of synthesis and accumulation of the capsaicinoids is the epidermal cells of the placenta in the fruit. Ultimately, the capsaicinoids are secreted extracellularly into receptacles between the cuticle layer and the epidermal layer of the placenta. These receptacles of accumulated capsaicinoids are macroscopically visible as pale yellow to orange droplets or blisters on the placenta of many chile types are odorless and tasteless (Guzman et al., 2010 and references therein).

While it is used as an ingredient in pepper sprays, capsaicin and its dihydro derivatives all exhibit anti-inflammatory properties (Sancho et al., 2002). Kim et al. (2003) examined the anti-inflammatory mechanism of capsaicin on the production of inflammatory mole cules in liposaccharides (LPS)-stimulated murine peritoneal macrophages. Capsaicin suppressed PGE2 production by inhibiting COX-2 enzyme and inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS) expression in a dose-dependent manner. Lee et al. (2000) showed capsaicin induced apoptosis in A172 human glioblastoma cells in a time and dose-dependent manner. The mechanism whereby capsaicin induced apoptosis may involve reduction of the basal generation of ROS.

In plants three pathways: shikimate, isoprenoid, and polyketide are particularly the source of most secondary metabolites. After the formation of the major basic skeletons, further modifications result in plant species specific compounds. The “decorations” concern, for example hydroxy, methoxy, aldehyde, carboxyl groups, and substituents adding further carbon atoms to the molecule, such as prenyl-, malonyl-, and glucosyl-moieties. Moreover, various oxidative reactions may result in loss of certain fragments of the molecule or rearrangements leading to new skeletons (Verpoorte and Alfermann, 2000).

The shikimate pathway is the major source of aromatic compounds (Bentley, 1990; Haslam, 1993; Herrmann, 1995; Schmidt and Amrhein, 1995). It is found in microorganisms and plants, but not in mammals. The main trunk of the shikimate pathway consists of reactions catalyzed by seven enzymes. The best studied of these are the penultimate enzyme, the 5-enol-pyruvoyl shikimate-3-P synthase, the primary target site for the herbicide glyphosate, and the first enzyme, DAHP synthase, controls carbon flow into the shikimate pathway. DAHP synthase catalyzes the condensation of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and erythrose-4-P to yield DAHP and Pi. Even though the enzyme was discovered in Escherichia coli more than three decades ago and has been purified to electrophoretic homogeneity from a number of sources, the fine structure of DAHP, the product of the enzyme-catalyzed reaction, was not described until many years later (Garner and Herrmann, 1984).

The pathway starts with the condensation of D-erythrose 4-phosphate and phosphoenolpyruvate. In a series of reactions a cyclic compound, 3-dehydroquinate, is obtained. In two further steps this yields shikimate, which after phosphorylation is coupled by the enzyme EPSP synthase with phosphoenolpyruvate to give 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate (EPSP). This enzyme is the target for glyphosate, the herbicide. Dephosporylation of EPSP eventually results in chorismate, from where the pathway diverges into two major branches, leading to respectively phenylalanine/tyrosine and tryptophan. In terms of carbon fluxes some minor branches lead to isochorismate, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, and 4-aminobenzoic acid, from which series of different secondary metabolites are derived. All branches lead to products necessary for primary metabolism and primary functions in cells, but also secondary metabolite pathways are derived from these branches. From an early intermediate of the shikimate pathway (3-dehydroshikimate) gallic acid derivatives are formed (Figure 2.12) (Verpoorte and Alfermann, 2000).

The majority of shikimate-derived natural products are formed from the end products of the shikimate pathway, i.e. the aromatic amino acids. Of these, phenylalanine in particular gives rise to a tremendous variety of different phenylpropanoid compounds, e.g. the flavonoids or the lignans (van Sumere and Lea, 1985; Haslam, 1993), although all three aromatic amino acids along with anthranilic acid are the precursors of numerous alkaloids (Southon and Buckingham, 1989; Haslam, 1993). A smaller number of natural products are derived from variants of the shikimate pathway, which branch off at different points along the main metabolic sequence. It not only generates end products that serve as the starting materials for the biosynthesis of countless natural products but, as a very complex metabolic pathway, it also provides ample opportunities for “derailments” along the pathway, which, through often very intriguing chemistry, lead to additional unique secondary metabolites line phenazines and esmeraldins, as has been reviewed by Floss (1997).

The classification based on biosynthetic origin has as major examples the terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, and polyketides with terpenoids as the largest group. These compounds are all derived from the isoprenoid biosynthetic pathway, which uses a C5 building block to build up C10 (monoterpenes), C15 (sesquiterpenes), C20 (diterpenes), C30 (steroids and triterpenes), and C40 (carotenoids) compounds. In the other two groups a few basic building blocks phenylalanine/tyrosine (C9) and acetate (C2), are used to assemble a basic skeleton from which respectively the phenylpropanoids and polyketides are derived. In Figure 2.12 some major group of secondary metabolites derived from the terpenoid and phenylpropanoid pathways in plants are summarized. These two pathways are most important for secondary metabolite formation in plants; the polyketide pathway is particularly well-developed in microorganisms.

The phenylpropanoid pathway is one of the most important metabolic pathways in plants in terms of carbon flux (Bentley, 1990; Haslam, 1993; Strack, 1997). In a cell more than 20% of the total metabolism can go through this pathway, the enzyme chorismate mutase is an important regulatory point. This pathway leads to, among others, lignin, lignans, flavonoids, and anthocyanins mediated by phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL), which converts phenylalanine into trans-cinnamic acid by a non-oxidative deamination (Verpoorte and Alfermann, 2000).

Cinnamate and its hydroxy-derivatives are also the precursor for a broad range of other phenolics such as coumarins, formed by lactonization after introduction of an ortho hydroxy group in cinnamate, and benzoic acid derivatives such as salicylic acid by cleavage at the double bond in the side chain of cinnamate. Conversion of the carboxylic group in the (hydroxy) cinnamates to an alcohol yields the building blocks for lignin and the lignans (Dawson et al ., 1989). The two major classes of alkaloids, the isoquinoline and the indole alkaloids, are derived from the aromatic amino acids. The isoquinoline alkaloids are formed from dopamine, which is condensed with 4-hydroxyphenyl acetaldehyde (both formed from tyrosine), yielding the benzylisoquinoline tiorcoclaurine. This compound in a series of steps is converted into reticuline, the precursor for numerous isoquinoline alkaloids such as morphine, sanguinarine, and berberine (Hashimoto and Yamada, 1994; Kutchan, 1995). Other types of phenolic compounds are derived from other branches of the chorismate pathway (Figure 2.12). For example, the isochorismate branch leads to anthraquinones (e.g. in some Rubiaceae plants). Naphtoquinones are derived from 4-hydroxybenzoic acid.

Figure 2.12 Terpenoid and shikimate pathways, two major routes leading to various secondary metabolites (Adapted from Verpoorte and Alfermann, 2000). GGP, geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate; FPP, farnesyl pyrophosphate; IPP, isopentenyl pyrophosphate; DMAPP, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate; Pyr, pyruvate.

The other important pathway in plants is that of the terpenoids, also known as isoprenoid pathway (Nes et al., 1992; McGarvey and Croteau, 1995; Torsell, 1997). Terpenoids include more than one third of all known secondary metabolites (Figure 2.13). Moreover, the C5-building block is also incorporated in many other skeletons, e.g. in anthraquinones, naphtoquinones, cannabinoids, furanocoumarines, and terpenoid indole alkaloids. In the “decoration” type of reactions in various types of secondary metabolites C5-units are attached to the basic skeleton, e.g. hop bitter acids, flavonoids, and isoflavonoids (Tahara and Ibrahim, 1995; Barron and Ibrahim, 1996).

The biosynthetic pathway to terpenoids (Figure 2.13) is conveniently treated as comprising four stages, the first of which involves the formation of isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), the biological C5 isoprene unit. Plants synthesize IPP and its allylic isomer, dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), by one of two routes: the well-known mevalonic acid pathway, or the newly discovered methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway. In the second stage, the basic C5 units condense to generate three larger prenyl diphosphates, geranyl diphosphate (GPP, C10), farnesyl diphosphate (FPP, C15), and geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP, C20). In the third stage, the C10–C20 diphosphates undergo a wide range of cyclizations and rearrangements to produce the parent carbon skeletons of each terpene class. GPP is converted to the monoterpenes, FPP is converted to the sesquiterpenes, and GGPP is converted to the diterpenes. FPP and GGPP can also dimerize in a head-to-head fashion to form the precursors of the C30 and the C40 terpenoids, respectively. The fourth and final stage encompasses a variety of oxidations, reductions isomerizations, conjugations, and other transformations by which the parent skeletons of each terpene class are converted to thousands of distinct terpene metabolites (Ashour et al., 2010).

Figure 2.13 Overview of terpenoids buisynthesis in plants, showing the basic stages of this process and major groups of ebd products. CoA, coenzyme A; GAP, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (adapted from Ashour and Gershenzon, 2010).

The most exciting advance in the field of plant terpenoid biosynthesis is the discovery of a second route for making the basic C5 building block of terpenes completely distinct from the mevalonate pathway (Lichtenthaler, 2000). This route, which starts from glyceraldehyde phosphate and pyruvate (Figure 2.13), has also been detected in bacteria and other microorganisms. Different studies have demonstrated that an assortment of terpenoids from angiosperms, gymnosperms, and bryophytes, including monoterpenes (Eisenreich et al., 1997), diterpenes (Knoss et al., 1997; Jennewein and Croteau, 2001), carotenoids (Lichtenthaler et al., 1997), and the side chains of chlorophyll (phytol) and quinones (Lichtenthaler et al., 1997) are formed in a non-mevalonate fashion, while the labeling of sesquiterpenes and sterols was consistent with their origin from the mevalonate pathway (Lichtenthaler et al., 1997).

The non-mevalonate route to terpenoids appears to be localized in the plastids. In plant cells, terpenoids are manufactured both in the plastids and the cytosol (Gray, 1987; Kleinig, 1989). As a general rule, the plastids produce monoterpenes, diterpenes, phytol, carotenoids, and the side chains of plastoquinone and α -tocopherol, while the cytosol/ER compartment produces sesquiterpenes, sterols, and dolichols. In the studies discussed here, nearly all of the terpenoids labeled by deoxyxylulose (Sagner et al., 1998; Eisenreich et al., 2001) and 2-C-methyl erythritol feeding (Duvold et al., 1997) or showing 13C-patterns indicative of a non-mevalonate origin (Cartayrade et al., 1994; Lichtenthaler et al., 1997; Eisenreich et al., 2001) are thought to be plastid derived. A strict division between the mevalonate and non-mevalonate pathways may not always exist for a given end product. The biosynthesis of certain terpenoids appears to involve the participation of both routes (Nabeta et al., 1995; Piel et al., 1998).

The poyketide pathway plays an important role in primary metabolism in the biosynthesis of fatty acids. The fatty acids are the basis for various secondary metabolites, but the polyketide pathway also directly leads to secondary metabolites, particularly in micro-organisms, but also in plants (Luckner, 1990; Borejsza-Wysocki and Hrazdina, 1996; Torsell, 1997). The C2 polyketide building block acetyl- CoA ester is first converted into the more reactive malonyl-CoA ester. This compound is then used in various reactions, also at the start of the mevalonate pathway (Figure 2.14). In the fatty acid biosynthesis, acetyl-CoA is the starter molecule, bound to a thiol group in the fatty acid synthetase enzyme complex, the malonyl-CoA is bound to another vicinal thiol group in the acyl carrier protein (ACP) and is subsequently condensed with the acetyl group. The acetoacetyl-ACP is reduced to give the butyryl-ACP, which reacts with a further malonyl-CoA, thus in a series of reactions the fatty acids are built up. From the fatty acid pathway various secondary metabolites, such as alkanes, acetogenins, and jasmonates are formed (Verpoorte and Alfermann, 2000).

Figure 2.14 Mevalonate pathway.

The malonyl-CoA is also part of the flavonoid biosynthesis, coumaryl-CoA is condensed with three molecules of malonyl-CoA, after which ring closure yields naringenin. The enzyme stilbene synthase results in the formation of stilbenes such as resveratrol using the same substrates. The condensation of coumaryl-CoA with one malonyl-CoA leads to benzalacetones (Borejsza-Wysocki and Hrazdina, 1996). Other examples of plant secondary metabolites derived from the polyketide pathway are 6-methylsalicylic acid and coniine (four C2 units), plumbagin (six C2 units), and anthraquinones (eight C2 units) (Figure 2.15). However, the anthraquinones are, in some plant families, derived from the chorismate pathway (Verpoorte and Alfermann, 2000).

Figure 2.15 Polyketide biosynthetic pathway leading to anthraquinones (from Verpoorte and Alfermann, 2000).

The cyclic terpenes formed initially are subject to an assortment of further enzymatic modifications, including oxidations, reductions, isomerizations, and conjugations, to produce the wide array of terpenoid end products found in plants. Unfortunately, few of these conversions have been well studied, and there is little evidence from most of the biosynthetic routes proposed, except in the case of the gibberellin pathway (Yamaguchi, 2008). Many of the secondary transformations belong to a series of well-known reaction types that are not restricted to terpenoid biosynthesis (Mihaliak et al., 1993). The enzymes involved are often cytochrome P450 enzymes, dioxygenases, and peroxidases.

The pathway of glucosinolate biosynthesis has been studied since the 1960s and the identity of many intermediates, enzymes, and genes involved is now known. The biosynthesis of glucosinolates was recently reviewed extensively by Halkier and Gershenzon (2006).

Kjaer and Conti (1954) suggested that amino acids may be natural precursors of the aglycone moiety of glucosinolates based on the similarities between the carbon skeletons of some amino acids and the glucosinolates. This hypothesis was confirmed by studies of the different biosynthetic stages. Most of these studies involved the administration of variously labeled compounds (3H, 14C, 15N, or 35S) to plants and the assessment of their relative efficiencies as precursors on the basis of the extent of incorporation of isotope into the glucosinolate. The classification of glucosinolates, as shown in Table 2.6, depends on the amino acid from which they are derived; aliphatic glucosinolates are derived from alanine, leucine, isoleucine, methionine, or valine; aromatic glucosinolates are derived from phenylalanine or tyrosine; and indole glucosinolates are derived from tryptophane (Sørensen, 1990).

The biosynthesis of glucosinolates from amino acids can be divided into three separate steps. The first step is the chain elongation of aliphatic and aromatic amino acids by inserting methylene groups into their side chains. Second, the metabolic modification of the amino acids (or chain-extended derivatives of amino acids) takes place via an aldoxime intermediate. The same modifications also occur in the biosynthetic route of cyanogenic glycosides. However, the co-occurrence of glucosinolates and cyanogenic glycosides in the same plant is very rare (an example is Carica papaya). The biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glycosides has been elucidated in more detail by Halkier and Lindberg-Møller (1991) and by Koch et al. (1992). Third, following the formation of the aldoxime, the glucosinolate is formed by various secondary transformations such as S-insertion, glucosylation, and sulfation. Further modification of the side chain can occur in the formed glucosinolate by, for example, oxidation and/or elimination reactions (Figure 2.16).

Figure 2.16 The simplified biosynthesis of the glucosinolate core structure.

Ambrosi, M., Cameron, N.R., and Davis, B.G. (2005) Lectins: tools for the molecular understanding of the glycocode . Organic and Biomolecular, 3 (9), 1593–1608.

American Association of Cereal Chemists (2001) The definition of dietary fiber. Report of the dietary fiber definition committee to the board of directors of the American Association of Cereal Chemists . Cereal Foods World, 46 (3), 112–126.

Anastas, P.T. and Warner, G.C. (1998) Green Chemistry: Theory and Practice, Oxford University Press, New York.

Andersen, B., Rassov, A., Westergaard, N., and Lundgren, K. (1999) Inhibition of glycogenolysis in primary rat hepatocytes by 1,4-dideoxy-1,4-imino-D-arabinitol . Biochemical Journal, 342 , 545–550.

Andrés-Lacueva, C., Medina-Remon, A., Llorach, R., Urpi-Sarda, M., Khan, N. Chiva-Blanch, G., Zamora- Ros, R., Rotches-Ribalta, M., and Lamuela-Raventós, R.M. (2010) Phenolic compounds: chemistry and occurrence in fruits and vegetables. In Laura A. de la Rosa, Emilio Alvarez-Parrilla and Gustavo A. Gonzalez-Aguilar (eds), Fruit and Vegetable Phytochemicals: Chemistry, nutritional value and stability. Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 53–87.

Armstrong, G.A. and Hearst, J.E. (1996) Carotenoids 2: Genetics and molecular biology of carotenoid pigment biosynthesis . Journal of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology , 10 (2), 228–37.

Arnaud, A. (1892) Sur un nouvel acide gras non saturé de la série CnH2n − 4O2. Bulletin de la Société Chimique de France, pp. 233–234.

Arnaud, M.A. (1902) Sur la constitution de l’acide taririque. Bulletin de la Société Chimique de France, pp. 489–496.

Asano, N. (2008) Glycosidase-Inhibiting alkaloids: isolation, structure, and application. In E. Fattorusso and O. Taglialatela-Scafati (eds) Modern Alkaloids: Structure, isolation, synthesis and biology, Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co . KGaA, Weinheim.

Ashour, M., Wink M., and Gershenzon, J. (2010) Biochemistry of terpenoids: monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes and diterpenes. In Wink M. (ed.) Biochemistry of Plant Secondary Metabolism, Annual Plant Reviews, Second Edition, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 258–303.