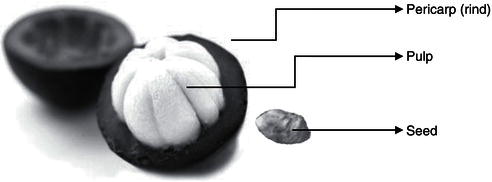

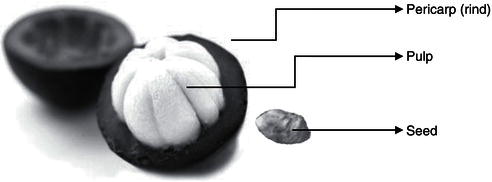

Figure 8.1 Composition of mangosteen.

The food industry produces large volumes of waste, both solid and liquid, resulting from the production, preparation, and consumption of food. These wastes pose increasing disposal and potential severe pollution problems and represent a loss of valuable biomass and nutrients. Besides their pollution and hazard aspects, in many cases, food processing wastes might have a potential for conversion into value-added products. Food processing wastes are those end products of various food processing industries that have not been recycled or used for other purposes. They are the non-product flows of raw materials whose economic values are less than the cost of collection and recovery for reuse; and are therefore discarded as wastes. These wastes could be considered valuable by-products if there were processed by appropriate technical means and if the value of the subsequent products were to exceed the cost of reprocessing (Schieber et al., 2001). The composition of wastes emerging from the food processing factories is extremely varied and depends on both the nature of the product and the production technique employed. For instance, waste from the meat industry contains high amounts of fat and proteins while waste from the canning industry contains high concentrations of sugars and starches. Fruits from temperate zones are usually characterized by a large edible portion and moderate amounts of waste material such as peels, seeds, and stones. In contrast, considerably higher ratios of by-products arise from tropical and subtropical fruit processing. Due to increasing production, disposal represents a growing problem since the plant material is usually prone to microbial spoilage, thus limiting further exploitation. One the other hand, cost of drying, storage, and shipment of by-products are economically limiting factors (Lowe and Buckmaster, 1995). Therefore, agro-industrial waste is often utilized as animal feed or fertilizer. However, demand for feed may be varying and dependent on agricultural yields. The problem of disposing by-products is further aggravated by legal restrictions. Thus, efficient, inexpensive, and environmentally sound utilization of these materials is becoming more important due to profitability.

Due to the high consumption of the edible parts of fruits such as orange, apple, peach, olive, etc. which are mainly commercialized in processed form, fruit wastes (consisting of peels, pomace, and seeds) are produced in large quantities in markets. These materials could be a restrictive factor in the commercialization of these products if it they are not usefully recovered, because they represent significant losses with respect to the raw materials, which considerably increases the price of the processed products and also causes a severe problem in the community as they gradually ferment and give off odors. This might be due to their lack of commercial application, however, nowadays these by-products can be converted to different high-added value compounds particularly the fiber fraction. For example, orange and lemon sub-products, which are abundant and cheap, also constitute an important source of fiber since they are very rich in pectins. Among many other bioactive compounds, significant amounts of pectins and polyphenols can be recovered from apple by-products; and different types of fibers are isolated from grapes, after the extraction of their juice, as well as from guava skin and pulp (Clifford, 2001). Since these fibers are associated with antioxidant compound acid derivatives, they constitute a multiple and complete dietary supplement. Other fibers of interest are those rich in highly branched pectins that can be isolated from the mango skin. Other waste products are those coming from the kiwi that contain about 25% fiber as a percentage of dry matter and from the pineapple shell that has a high percentage of insoluble fiber (70% total fiber), which is mainly composed of neutral sugars, such as xylose and glucose, and presents a great antioxidant capacity. Olives that are largely destined for the production of olive oil also leave a by-product that is rich in different bioactive components, including dietary fiber.

Large amounts of fruit and vegetable processing wastes are produced from packing plants, canneries, etc., which may be disposed of in several ways including immediate use for landfill or drying to a stable condition (about 10% moisture) in order to use as animal feed out of season, or which, alternatively, may be processed biotechnologically in order to produce single cell protein (SCP). Industry continues to make progress in solving waste problems through recovery of by-products and waste materials such as peel, pulp, or molasses by the employment of the fermentation process. The protein content of fruit and vegetable processing wastes with an adequate level of fermentable carbohydrates can be increased to 20–30% by using solid substrate fermentation. The composition of some fruits and vegetables indicates that many have a significant proportion of fermentable sugars. Of these, oranges, carrots, apple, and peas have been successfully utilized as a substrate in the fermentation. Vinegar, citric acid, and acetic acid are produced from the by-products of the fruit and vegetable industry.

Due to the large amounts being processed into juice, a considerable by-product industry has evolved to utilize the residual peels, membranes, seeds, and other wastes. Residues of citrus juice production are a source of dried pulp and molasses, fiber, pectin, cold-pressed oils, essences, D-limonene, juice pulps, and pulp wash, ethanol, seed oil, limnoids, and flavonoids (Askar, 1998; Braddock, 1995; Ozaki et al., 2000). Citrus juice processing is one of the important food industries of the world, yielding an enormous quantity of processing residues. Juice recovery from citrus fruit is about 40–55%, with the processing residue consisting of peel and rag, pulp wash, seeds, and citrus molasses. Most of the citrus fruits peels contain fibers and pectin, which can easily be recovered. The main flavonoids found in citrus species are hesperidin, narirutin, naringin, and eriocitrin (Mouly et al., 1994). Peels and other solid residues of citrus waste mainly contain heperidin and eriocitrin, while the naringin and eriocitrin are predominantly found in liquid residues (Coll et al., 1998). Citrus seeds and peels have been reported as having high concentrations of flavonoids and have been tested for their antioxidative properties (Benavente-Garcia, 1997; Manthey et al., 2001). Citrus by-products and wastes also contain large amount of coloring materials in addition to their complex polysaccharide contents. Hence, they are a potential source of natural clouding agents for many beverages. Sreenath et al. (1995) reported that citrus by-products could be utilized as natural sources for the production of beverage clouding agents using fermentation techniques, pectinolytic treatments, and alcohol extraction. They also evaluated the strength and stability of prepared clouds in model test beverage systems to determine their similarities to commercially available beverage cloud types.

Mango (Mangifera indica L., Anacardiaceae) is one of the most important tropical fruits. Major wastes from mango processing are peels and stones, amounting to 35–60% of the total fruit weight (Larrauri et al., 1996). Mango is one of the world’s most popular tropical fruits with total production worldwide being around 25 million metric tons a year followed by banana, pineapple, papaya, and avocado. Because it is a seasonal fruit, approximately 20% of fruits are processed into various other forms such as puree, juices, nectar, pickles, canned slices, and dried fruits. Mango consists of 33–85% edible pulp, with 9–40% inedible kernel and 7–24% inedible peel. So, during industrial processing of mango, peel is a major by-product that is discarded as waste without any commercial purpose and is becoming a source of pollution. However, in recent studies, few scientific investigations have examined the importance of mango peels as a dietary fiber and natural antioxidant source.

Dietary fiber content ranged from 45 to 78% of mango peel and was found at a higher level in ripe peels. Dietary fiber in mango peel has recently been shown as a favorable source of high quality polysaccharides, because it not only has high starch, cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, and pectin content but also has low lipid content. In addition, in vitro starch studies predicted low glycaemic responses from mango peel fiber (Ajila et al., 2007; Vergara-Valencia, 2007).

Mango peel extract offers a rich and inexpensive source of valuable compounds such as antioxidant compounds and dietary fiber, thus it shows potential as a functional food or value added ingredient. Therefore, mango peel if conveniently processed, could furnish useful products that may balance out waste treatment costs and also decrease the cost of main products. This new source will potentially be a functional food or value added ingredient in the future in our dietary system. There is scope for the isolation of these active ingredients and also use of mango peel as an ingredient in processed food products such as bakery products, breakfast cereals, pasta products, bars, and beverages. For example, incorporation of mango peel powder in macaroni not only increased the polyphenol, carotenoid, and dietary fiber contents but also exhibited improved antioxidant activity. The studies on cooking quality, textural, and sensory evaluations showed that these macaroni had good acceptability (Ajila et al., 2010). Beside this, the kernel has also been found to be a potentially good source of nutrients for human and animal feed with 44.4% moisture content, 6.0% protein, 12.8% fat, 32.8% carbohydrate, 2.0% crude fiber, 2.0% ash, and 0.39% tannin (Elegbede et al., 1995).

Mango seed kernel fat is a source of edible oil and has attracted attention due to having higher amounts of unsaturated fatty acids. Mango seed kernels may also be used as antioxidants. The major phenolics in mango seed kernels are gallic, egallic acids, gallates, and gallotanins (Puravankara et al., 2000; Arogba, 2000). Ethanolic extracts of mango seed kernels displayed a broad antimicrobial spectrum and were more effective against Gram-positive than against Gram-negative bacteria (Kabuki et al., 2000). Mango peels were also reported to be a good source of dietary fiber containing high amounts of extractable polyphenols (Larrauri et al., 1996; Larrauri et al., 1997; Larrauri, 1999). Mango latex which is deposited in fruit ducts and removed with the fruit at harvest has been shown to be a source of monoterpenes (John et al., 2003).

Passion fruit, which botanically belongs to the family of Passifloraceae, of the genus Passiflora with the scientific name Passiflora edulis, is native to subtropical wild regions of South America probably originating in Paraguay. Over 500 cultivars exist; however, two main types, purple and yellow passion fruits, are widely cultivated. The ripening fruit is oval-shaped (average weight 35–50 g) with thick rind, smooth waxy surface and fine white specks. However, fruits with wrinkled surfaces actually have more flavor and are rich in sugar. Inside, it consists of membranous sacs containing light orange-colored, pulpy juice with numerous tiny, hard, dark brown or black, pitted seeds. The waste resulting from passion fruit processing consists of more than 75% of the raw material. The rind constitutes 90% of the waste and is a source of pectin (20% of the dry weight). Passion fruit seed oil is rich in linoleic acid (65%) (Askar, 1998).

Beside the pleasant taste of sweet and tart, passion fruit is rich in health benefiting plant nutrients, low in sodium and very low in saturated fat and cholesterol. It is also a good source of potassium, vitamin A, and vitamin C and a very good source of dietary fiber (10.4 g or 27% is contained in 100 g of fruit pulp).

Chi-Fai and Huang (2004) reported on the evaluation and compared the composition, physicochemical properties, and in vitro hypoglycemic effect of different fiber-rich fractions prepared from the seeds of passion fruits indigenous to Taiwan (hybrid, Tai-Nong-1). In this study, the contents of seed and pulp in the fresh passion fruit were about 11.1 ± 0.35 and 88.9 ± 0.35 g/100 g, respectively.

Table 8.1 illustrates that the edible passion fruit seed was rich in insoluble fiber-rich fractions (insoluble dietary fiber, alcohol-insoluble solids, and water-insoluble solids) which are mainly composed of cellulose, pectic substances, and hemicellulose. The result of this study also revealed that these fiber-rich fractions had water- and oil-holding capacities (2.07–3.72 g/g relatively greater than 0.9–1.3 g/g of some orange by-product fibers) comparable with those of cellulose, while their bulk densities and cation-exchange capacities were significantly higher than those of cellulose. Moreover, the in vitro study indicated that all insoluble fiber-rich fractions showed significant effects in absorbing glucose and retarding amylase activity, it is speculated that these fiber-rich fractions might have potential benefit for controlling postprandial serum glucose, and potential applications as low calorie bulk ingredients for fiber enrichment and dietetic snacks.

Table 8.1 Chemical composition of the raw and defatted passion fruit seed

| Composition | g/100 g raw seed (dry weight) | g/100 g defatted seed(dry weight) |

| Moisture | 6.60 ± 0.28 | – |

| Crude protein | 8.25 ± 0.58 | 10.8 ± 0.75 |

| Crude lipid | 24.5 ± 1.58 | – |

| Total dietary fiber (TDF) | 64.8 ± 0.05 | 85.9 ± 0.07 |

| Insoluble dietary fiber (IDF) | 64.1 ± 0.02 | 84.9 ± 0.03 |

| Soluble dietary fiber (SDF) | 0.73 ± 0.07 | 0.97 ± 0.09 |

| Ash | 1.34 ± 0.08 | 1.77 ± 0.11 |

| Carbohydrate | 1.11 | 1.53 |

Beside this, the yellow passion fruit rind is the by-product from the juice industry available in large quantities (Yapo and Koffi, 2008). By using AOAC enzymatic − gravimetric method, the total dietary fiber in alcohol-insoluble material from yellow passion fruit rind was more than 73% dry matter of which insoluble dietary fiber accounted for more than 60% (w/w). The determination of dietary fiber using the hydrolysis method revealed that non-starchy polysaccharides were the predominant components (about 70%, w/w), of which cellulose appeared to be the main fraction. The water holding and oil holding capacities of the fiber-rich material were more than 3 g of water/g of fiber and over 4 g of oil/g of fiber, respectively. So, dietary fiber from yellow passion fruit rind, prepared as alcohol-insoluble material, may be suitable to protect against diverticular diseases.

The pomegranate fruit can be consumed directly as fresh seed and fresh juice. Pomegranate contains highly colored grains which give a delicious juice. The presence of anthocyanins is responsible for the red color of its juice and other products of pomegranate fruit. Polyphenols are the major class phytochemicals in pomegranate fruit, including flavonoids (anthocyanins), condensed tannins (pro-anthocyanin), and hydrolysable tannins (ellagitannins and gallotannins) (Guo et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2006; Barzegar et al., 2007; Al-Zoreky, 2009).

The mangosteen is one of the most praised tropical fruits: known as mangosteen (English), mangostan (Spanish), mangostanier (French), manggis (Malaysian), manggustan (Philippine), mongkhut (Cambodian), and mangkhut (Thai). Garcinia mangostana L. has been known in name as mangosteen, in the family Guttiferae. Mangosteen fruit is approximately 3.5–7 cm across and weighs about 60–150 g. The woody skin of its pericarp (rind) varies from thin to thick, about 6–10 mm. Peels are pale green when immature and dark purple when ripe. Juice from mangosteens are produced from whole fruit or mixed polyphenols extracted from the inedible rind. This formulation improves phytochemical value in beverages. The juice has a purple color and astringency due to pigments from the pericarp including xanthonoids. It is produced and sold in dietary supplement forms, such as juice or capsule. The juice of mangosteen is often combined with other juices, such as grape, blueberry, raspberry, apple, cherry, and strawberry to improve the taste. The marketing promotions for these products present the advantages of compounds from mangosteen as (1) providing antioxidants against free radicals in the human body, (2) reducing inflammation, (3) reducing allergies, (4) maintaining immune system health, and (5) preventing cancer.

Figure 8.1 Composition of mangosteen.

Table 8.2 Proximate composition of mangosteen seed

| Component | Amount (%) |

| Moisture | 13.08 |

| Carbohydrate | 43.50 |

| Crude protein | 6.47 |

| Crude fat | 21.18 |

| Crude fiber | 13.70 |

| Ash | 1.99 |

The pericarp of mangosteen varies in thickness. Its color is a yellowish-white to reddish-purple color depending on level of maturity (Figure 8.1), being reddish-purple when ripe, and it comprises bitter substances, mostly tannins and xanthones. The pericarp of mangosteens contains more xanthones than other fruits with medicinal properties and is traditionally used to treat diarrhoea and skin infections.

One to three larger segments of pulp contain recalcitrant seeds. Mangosteen seeds are not true seeds because they develop from the inner carpel wall, sometimes polyembryonic as an underdeveloped embryo. The seed of mangosteen is apomictic seed that is different from other common fruits. The apomictic seeds are viable for a short period of about three days if dried. Therefore, seeds must be kept moist to remain viable until planting and germination. The best way to keep them is in moist material or within the fruit, which can keep viability.

Ajayi and coworker (2006) reported seeds of mangosteen had high amount of carbohydrate, about 43.5%, and lipid, 21.18%, while protein content was low at only about 6.57% (Table 8.2). The seed powder is a good source of minerals because it contains high levels of potassium, magnesium, and calcium.

Generally, compounds from mangosteen have similar properties to other fruits, and been used as a health supplements and to support treatment of diseases. Mangosteen pericarp consists of an array of polyphenols including mostly xanthones and tannins which create astringency. Bioactive compounds in mangosteen pericarp are mostly in groups of polyphenolic compounds including xanthones, anthocyanin, proanthocyanidins, and catechin. Chaovanalikit and Mingmuang (2008) reported that the internal mangosteen pericarp has the highest of all phenolic compounds: 3404 mg GAE/100 g, 2930.49 mg GAE/100 g on external mangosteen pericarp, and 133.29 mg GAE/100 g in pulp.

Xanthones are one of the biologically active compounds and are unique among the group of polyphenolic compounds. The mangosteen pericarp contains more xanthones than other fruit sources. In nature, xanthones are found in very restricted families of plants, the majority being in the Gentianaceae and Guttiferae families. Xanthones can be briefly categorized into five groups including: (1) simple oxygenated xanthones, (2) prenylated, (3) xanthone glycosides, (4) xanthonolignoids, and (5) miscellaneous xanthones (Sultanbawa, 1980; Jiang et al., 2004). About 50 types of xanthones are found in the mangosteen and all of them have the same structural backbones. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is used to detect and classify the type of xanthones in mangosteen pericarp. The important xanthones in mangosteen, are α-mangostin, β-mangostin, 3-isomangostin, 9-hydroxycalabaxanthone, gartanin, and 8-desoxygartanin (Ji et al., 2007; Walker, 2007). There are numerous potential medicinal properties of xanthones, such as antiallergic, antituberculotic, anti-inflammatory, antiplatelet, and anticonvulsant properties (Marona et al., 2001). Xanthones have the molecular formula C13H8O2. and six-carbon conjugated ring structure characterized by multiple double carbon bonds that confer stability on the compounds. The various xanthones found are unique because the side chains can be attached to the carbon molecules due to their versatility. Xanthone content increases in amount and type of compounds depending on the ripening levels of the fruit. Chaovanalikit and Mingmuang (2008) reported that external mangosteen pericarp has the highest anthocyanin content of 179.49 mg Cyn-3-Glu/100 g, with 19.71 mg Cyn-3-Glu/100 g in internal mangosteen pericarp but none in the pulp. Moreover, the anthocyanins in the external pericarp of mangosteen are composed of six compounds: cyaniding-sophoroside, cyaniding-glucoside-pentoside, cyaniding-glucoside, cyaniding-glucoside-X, cyaniding-X2 and cyaniding X, where X is an unidentified residue (Palapol et al., 2008). Cyanidin-3-sophoroside and cyaniding-3-glucoside are the main compounds, which increase the color of the as it ripens.

Proanthocyanidin, a specific type of polyphenol, called flavonoids (flavan-3-ols), is one of the interesting components in grape seeds. There are many sources of proanthocyanidins, especially grapes, cranberries, and others. This substance is most abundantly found in grape seeds and mangosteen pericarps. It occurs naturally as a plant metabolite in fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, and flowers (Bagchi et al., 1997). Normally levels of proanthocyanidins are high in the outer shells of seeds and the bark of trees, helping to prevent degradation of some elements in plants due to oxygen and light.

The seeds of mangosteen are reported to contain about 21.18% oil (Ajayi et al., 2006). Oil that is extracted from mangosteen seeds is liquid at room temperature and golden-orange in color. The seeds contain both essential and non-essential fatty acids that, as can be seen from preliminary toxicological evaluation, are not harmful to the heart and liver of rats; hence the seed oil can be useful as edible oil. Fatty acids that were found in seeds of mangosteen are shown in Table 8.3.

The most abundant fatty acid is palmitic acid, that is, saturated fatty acid. Moreover, other unsaturated fatty acids are found in seeds including stearic acid, oleic acid, linoleic acid, gadoleic acid, and eicosadienoic acid. The most widespread unsaturated fatty acid is oleic acid which is about 34% of total oil from mangosteen seeds. In conclusion, the total unsaturated fatty acid is about 34%, while the total saturated fatty acid is 49.5% and unknown fatty acids are 5.14%.

Table 8.3 Fatty acids composition of mangosteen seed

| Common name | Lipid name | Amount (%) |

| Palmitic acid | C16: 0 | 49.5 |

| Stearic acid | C18: 1 | 1.33 |

| Palmitoleic acid | C16: 1 | ND* |

| Oleic acid | C18: 1 | 34.2 |

| Linoleic acid | C18: 2 | 1.03 |

| Linolenic acid | C18: 3 | ND* |

| Arachidic acid | C20: 0 | 8.77 |

| Gadoleic acid | C20: 1 | 0.10 |

| Eicosadienoic acid | C20: 2 | 0.11 |

| Behenic acid | C22: 0 | ND* |

| Lingnoceric acid | C24: 0 | ND* |

| Unknown | – | 5.14 |

| Total saturated fatty acid | 59.6 | |

| Total unsaturated fatty acid | 35.3 | |

*ND: not detected.

Apple pomace has been used in production of pectin. In comparison to citrus pectin, apple pectin is characterized by superior gelling properties. However, the slight hue of apple pectin caused by enzymatic browning may lead to limitations with respect to use in very light colored-foods. Attempts at bleaching apple pomace by alkaline peroxide resulted in the loss of the polyphenols and in pectin degradation (Renard et al., 1997). Apple pomace has been shown to be a good source of polyphenols, which are predominantly localized in the peels and are extracted into the juice to a minor extent. Major compounds isolated and identified include catechins, hydroxycinnamtes, phloretin glycosides, and quercetin. Some phenolic compounds from apple pomace have been found to exhibit stronger antioxidant activity in vitro (Lu and Foo, 1997; Lu and Fu, 1998; Lu and Foo, 2000). Anthocyanins are found in the vacuoles of epidermal and subepidermal cells of the skin of red apple varieties (Lancaster, 1992; Soji et al., 1999; Alonso-Salcer et al., 2001). Enhanced release of phenolics by enzymatic liquification with pectinase and cellulases represents an alternative approach to utilizing apple pomace (Will et al., 2000).

Apart from oranges, grapes (Vitis sp., Vitaceae) are the world’s largest fruit crop with more than 60 million tons produced annually. About 80% of the total crop is used in wine making and pomace represents approximately 20% of the weight of the grapes processed. A great range of products such as ethanol, tartrates, citric acid, grape seed oil, hydrocolloids, and dietary fiber are recovered from grape pomace (Bravo and Saura-Calixto, 1998; Nurgel ad Canbas, 1998). Anthocyanins, catechins, flavonol glycosides, phenolic acids, alcohols, and stillbenes are the principal phenolic constituents of grape pomace. Catechin, epicatechin, epicatechin gallate, and epigallocatechin are the major constitutive units of grape skin tannins (Souquet et al., 1996). Aminoethylthio-flavan-3-ol conjugates have been obtained from grape pomace by thiolysis of polymeric proanthocyanidins in the presence of cysteamine (Torres and Bobet, 2001). Grape seeds and skins are excellent sources of proanthocyanidins, flavonols, and falvan-3-ols (Souquet et al., 1996; Souquet et al., 2000). Procyanidins are the predominant proanthocyanidins in grape seeds, while procyanidins and predelphinidins are dominant in grape skins and stems. A number of stillbenes, namely trans-and cis-reservatrols (3,5,4’-trihydroxystilbene), trans- and cis-piceids (3-O-β-D-glucosides of resveratrol), trans-and cis-astringins (3-O-β-D-glucosides of 3’-hydroxyresveratrol). cis-resveratrolosides (4’-O-β-D-glucosides of resveratrol), and pterostilbene (a dimethylated derivative of stilbene) have been detected in both grape leaves and berries (Souquet et al., 2000; Cheynier and Rigaud, 1986).

Banana represents one of the most important fruit crops, with a global annual production of more than 50 million tons. Worldwide production of cooking bananas amounts to nearly 30 million per year. Peels constitute up to 30% of the ripe fruit. Attempts at utilization of banana waste include the biotechnological production of protein (Chung and Meyers, 1979), ethanol (Tewari et al., 1986), α-amylases (Krishna and Chandrasekaran, 1996), and cellulases (Krishna 1999). Banana peel contains a lot of phytochemical compounds, mainly antioxidants. The total amount of phenolic compounds in banana (Musa acuminata Colla AAA) peel ranges from 0.90 to 3.0 g/100 g DW (Someya et al., 2002). Ripened banana peel also contains other compounds, such as the anthocyanins delphinidin, cyanidin, and catecholamines (Kanazawa and Sakakibara, 2000). Furthermore, carotenoids, such as β-carotene, α-carotene, and different xanthophylls have been identified in banana peel in the range of 300–400 µg lutein equivalents/100 g (Subagio et al., 1996), as well as sterols and triterpenes, such as β-sitosterol, stigmasterol, campesterol, cycloeucalenol, cycloartenol, and 24-methylene cycloartanol (Knapp and Nicholas, 1969).

During processing of tomato juice, about 3–7% of the raw material is lost as waste. Tomato pomace consists of the dried and crushed skins and seeds of the fruits. The seeds account for approximately 10% of the fruit and 60% of the total waste, respectively, and are a source of protein (35%) and fat (25%). Due to an abundance of unsaturated fatty acids, tomato seed oil is getting unique interest (Askar, 1998). Lycopene is the principal carotenoid causing the characteristic red hue of tomatoes. Most of the lycopene is associated with the water-insoluble fraction and the skin (Sharma and Maguer, 1996). Supercritical CO2 extraction of lycopene and β-carotene from tomato paste waste resulted in recoveries up to 50% when ethanol was added as a solvent (Baysal et al., 2000).

Despite considerable improvements in processing techniques, including the use of depolymerizing enzymes, mash heating, and decanter technology, a major part of valuable compounds such as carotenes, uronic acids, and neutral sugars is still retained in the pomace, which is usually disposed of as feed or fertilizer. Juice yield is reported to be only 60–70%, and up to 80% of carotene may be lost with the pomace (Sims et al., 1993). Stoll et al. (2001) found 2 g/kg dry matter of total carotene content of pomace, depending on the processing conditions. Attempt has been made to incorporate carrot pomace into various food such as bread, cake, dressing, and pickles; and in the production of functional drinks.

There are three different kinds of mulberry: (1) red mulberry (Morus rubra), with dark purple edible fruit, (2) black mulberry (Morus nigra), with dark foliage and fruit, and (3) white mulberry (Morus alba), which is thin, glossy, and light green in color, with quite a variable leaf shape even on the same tree. White mulberry is primarily used for raising silkworms, which utilize the leaves as their main food source. These leaves are highly nutritious and the fruits boast high medicinal value in their amino acids, vitamin C, and antioxidants; the leaves can also be effective in regulating fat and boosting metabolism (Bae and Suh, 2007). There are many uses for the mulberry leaf and fruit. In China, Japan, and European countries this plant has a huge market for its medicinal and cosmetic value. Consuming mulberry leaf tea can be relaxing for the body and mind and is generally recommended for treating diabetes and hypertension (Herald, 2005).

Cassava or tapioca is an important economic root crop grown in Southeast Asia as well as in tropical Africa and Central America. Cassava leaves are a by-product of cassava roots’ harvest (depending on the varieties), which is rich in proteins, minerals, vitamins B1, B2, C, and carotenes (Eggum, 1970; Ravindran and Blair, 1992; Adewusi and Bradbury, 1993; Aletor and Adeogum, 1995). The protein content of cassava leaves is high for a non-leguminous plant. Although cassava leaves are rich in protein, other minerals such as crude fiber may limit their nutritive value for monogastric animals. Rogers and Milner (1963) reported a range of 4.0–15.2%. Immature cassava leaves were evidently used in the above analyses, since values as high 29% have been reported for mature leaves (Ravindran et al., 1982). Roger and Milner (1963) were the first to conduct detailed analyses of amino acid content of cassava leaves. They analyzed the leaves of 20 Jamaican and Brazilian cultivars obtained from ten month old healthy cassava and found that protein from the leaf was deficient in methionine, possibly marginal in tryptophan, but rich in lysine. In addition, there are natural compounds such as toxicant or antinutritional compound, cyanogenic glycosides, and tannins (Ravindran, 1993). The toxic properties associated with fresh cassava leaves are due to the hydrocyanic acid that is liberated when their cyanogenic glycosides, namely linamarin and lotaustralin, are hydrolyzed by endogenous enzymes. These strong complexes reduce the digestibility of protein and may have inhibited the activities of proteolytic enzymes like pepsin and trypsin (Chavan et al., 1979). Tannins are reduced by soaking in alkali solutions, for example sodium hydroxide, potassium hydroxide, and sodium carbonate, and with heating.

After rice is harvested and dried, the first stage of processing is de-husking, followed by milling where the bran layer is removed to produce white rice. The bran layer commonly termed as rice bran consists of the aleurone layer, part of the embryo, germ, and endosperm. Rice bran is a good source of nutrients and it is well-known that a major fraction contains approximately 12–15% protein, 15–20% fat, and 7–12% fiber. Defatted rice bran is the by-product of rice bran oil extraction. It generally contains 12–19% protein, 0.5–7% fat, and 5.5–14.5% fiber. Defatted rice bran is free flowing, light in weight, and has tendency to form dust. In the proper process, it is light in color but will be dark red after being desolved under too drastic conditions. Defatted rice bran is normally used as animal feed with a low economic value. Besides, it is utilized for food supplements, such as binder in sausage and raw material for hydrolyzed vegetable protein. Moreover, it is widely used in bakery products such as doughnuts, pancakes, muffins, breads, and cookies because it can improve quantity of dough, and increase amino acid, vitamin, and mineral content. In breakfast cereals and wafers defatted rice bran is used to improve absorption capacity, appearance, and flavor.

Figure 8.2 Basic steps for extraction of bioactive compounds from food plant by-products.

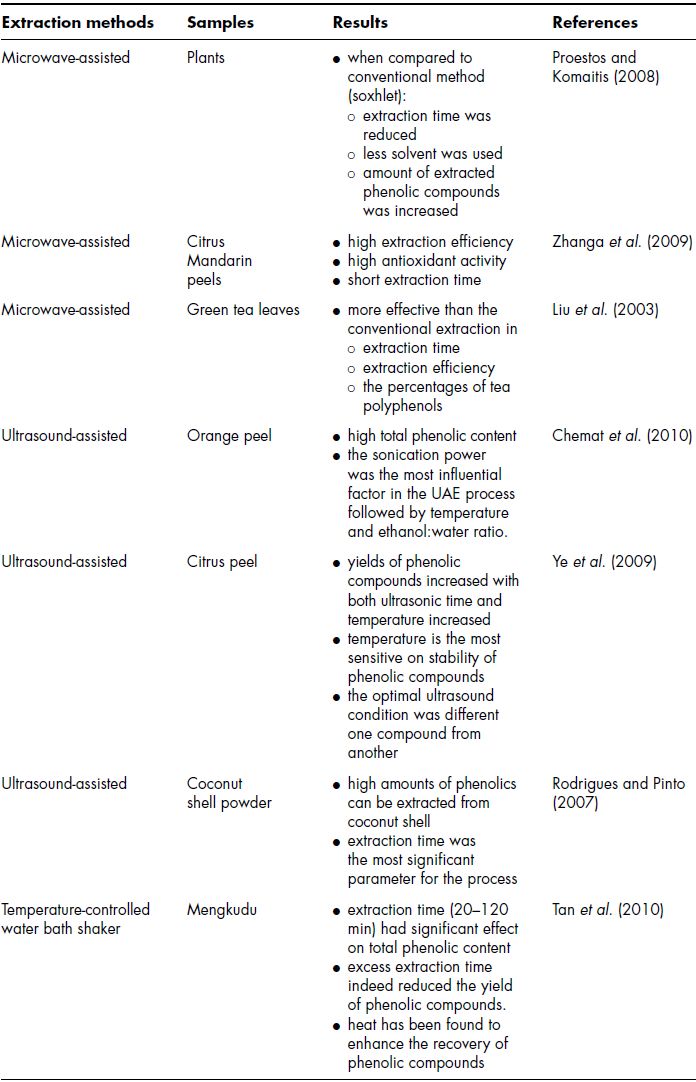

Steps for extraction of bioactive compounds or other components are different for every matrix depending on the selection and suitability for various materials. Figure 8.2 shows the basic steps for extracting compounds among which important steps are the drying and extraction processes. There are many methods of drying and extraction that can be used in a laboratory and in industry. Basic principles for extraction of bioactive compounds are identical for whole foods and for byproducts. Detailed extraction techniques are discussed in Chapters 17 and 18. Table 8.4 outlines some of the extraction methods and conditions for extracting bioactive compounds from by-products of the food industry.

Agro-waste cannot be regarded as waste but will likely become an additional resource to augment existing natural materials. Recycling, reprocessing, and eventual utilization of plant food processing residues offer potential of returning these by-products to beneficial uses rather than merely discharging into the environment causing detrimental environmental effects. The reprocessing of those wastes could involve rendering the recovered by-products suitable for beneficial use; promotion in suitable markets ensuring the profitability; suitable and economic reprocessing technology; and creation of an overall enterprise that is acceptable and economically feasible. The exploitation of by-products of plant food processing as a source of functional compounds and their application in food is a promising field, requiring cross-cutting technologies.

Table 8.4 Effects of extraction methods and extraction conditions.

Adewusi, S.R.A. and Bradbury, J.H. (1993) Carotenoid in cassava; comparison of open column and HPLC method of analysis. Journal of the Science of Food Agriculture, 62, 375–383.

Ajayi, I.A., Oderinde, R.A., Ogunkoya, B.O., Egunyomi, A., and Taiwo, V.O. (2006) Chamical analysis and preliminary toxicological evaluation of Garcinia mangostana seeds and seed oil. Journal Food Chemistry, 101, 999–1004.

Ajila, C.M., Naidu, K.A., Bhat, S.G., and Prasada Rao, U.J.S (2007) Bioactive compounds of mango peel extract. Food Chemistry, 105, 982–988.

Ajila, C.M., Aalawi, M., Leelavathi, K., and Prasad Rao, U.J.S. (2010) Mango peel powder: A potential source of antioxidative and dietary fiber in macaroni preparations. Innovative Food Science and Emerging Technologies, 11, 219–224.

Aletor, O., Oshodi, A.A., and Ipinmoroti, K. (2002) Chemical composition of common eafy vegetables and functional properties of their leaf protein concentrates. Food Chemistry, 78, 63–68.

Alonso-Salcer, R.M., Korta, E., Barranco, A., Berrueta, L.A., Gallo, B., and Vicente, J. (2001) Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, 49, 3761–3767.

Alapol, Y., Ketsa, S., Stavenson, D., Cooney, D.M., Allan, A.C., and Ferguson, I.B. (2008) Colour development and quality of mangosteen (Garinia mangostana L.) fruit during ripening and after harvest. Journal Postharwest Biology and Technology, 51, 349–353.

Al-Zoreky, N.S. (2009) Antimicrobial activity of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) fruitpeels. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 134, 244–248.

Andres, A., Bilbao, C., and Fito, P. (2004) Drying kinetics of apple cylinders under combined hot air-microwave dehydration. Journal of Food Engineering, 63, 71–78.

Argoba, S.S. (2000) Mango (Mangifera indica) kernel: chromatographic analysis of the tannin, and stability study of the associated polyphenol oxidase activity. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis, 13, 149–156.

Arsdel, W.B.V., Copley, M.J., and Morganm, A.I., Jr. (1973) Food Dehydration. In W.B. Van Arsdel, M.J. Copley, and A.I. Morgan, Jr., Drying Methods and Phenomena, second edition, volumes 1 and 2, The AVI Publishing Company, Inc. Westport, Connecticut.

Askar, A. (1998) Importance and characteristics of tropical fruits. Fruit Processing, 8, 273–276.

Bae, S.H. and Suh H.J. (2007) Antioxidant activities of five different mulberry cultivars in Korea. LWT – Food science and Technology, 40, 955–962.

Bagchi, D., Krohn R.L., and Bagchi M. (1997) Oxygen free radical scavenging abilities of vitamins C and E, and a grape seed proanthocyanidin extract in vitro. Molecular Pathology and Pharmacology, 95, 179–189.

Bagchi, D., Bagchi, M., Stohs, S.J., Ray, S.D., Sen, C.K., and Pruess, H.G. (2002) Cellular protection with proanthocyanidins derived from grape seeds. Annals of New York Academy of Science, 957, 260–270.

Barbieri, S., Elustondo, M., and Urbicain, M. (2004) Retention of aroma compounds in basil dried with low pressure superheated steam. Journal of Food Engineering, 65, 109–115.

Baysal, T., Ersus, S., and Starmans, D.A.J. (2000) Supercritical CO2 extraction of β-carotene and lycopene from tomato paste waste. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, 48, 5507–5511.

Balasundram, N., Sundram, K., and Samman, S. (2006) Phenolic compounds in plants and agri-industrial by-prodcuts: Antioxidant activity, Occurrence and potential uses. Food Chemistry, 99, 191–203.

Barzegar, M., Yasoubi, P., Sahari, M.A., and Azizi, M.H. (2007) Total Phenolic Contents and Antioxidant Activity of Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) Peel Extracts. Journal of Agricultural Science and Technology, 9, 35–42.

Benavente-Garcia, O., Castillo, J., Marin, F. R., Ortuno, A., and Del Rio, A. (1997) Uses and properties of citrus flavonoids. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 45, 4505–4515.

Boudhrioua, N., Bahloul, N., Slimen, I.B., and Kechaou, N. (2009) Comparison on the total phenol contents and the color of fresh and infrared dried olive leaves. Industrial Crops and Products, 29, 412–419.

Broillard, R. (1982) Chemical structure of anthocyanins. In Anthocyanins as Food Colors, Markakis, P. (ed.), Academic Press, New York, pp. 1–40.

Bravo, L. (1998) Polyphenols: chemistry, dietary sources, metabolism, and nutritional significance. Nutrition Reviews, 56, 317–333.

Braddock, R.J. (1995) By-products of citrus fruit. Food Technology, 49, 74–77.

Bravo, L. and Saura-Claxito, F. (1998) Characterization of dietary fiber and the in vitro indigestible fraction of grape pomace. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 49, 135–141.

Cai, J., Liu, X., Li, Z., and An, C. (2003) Study on extraction technology of strawberry pigments and its physicochemical properties. Food and Fermentation Industries, 29, 69−73.

Chi-Fai, C. and Huang Y. (2004) Characterization of passion fruit seed fibers—A potential fiber source. Food Chemistry, 85, 189–194.

Chaisawadi, S., Thongbutr, D., Kulamai, S., Methawiriyasilp, W., and Juntawong, P. (2005) Clean production of freeze-dried Kaffir lime powder. 31st Congress on Science and Technology of Thailand at Suranaree University of Technology, 18–20 October, 2005.

Chaovanalikit, A. and Mingmuang, A. (2008) Anthocyanin and total phenolic contents of mangosteen and its juices. SWU Scientific Journal, 23, 68–78.

Chavan, J.K., Kadam, S.S, Ghonsikar, C.P., and Salunkhe, D.K. (1979) Removal of tannins and improvement of in vitro protein digestibility of sorghum seeds by soaking in alkali. Journal of Food Science, 44, 1319–1321.

Chemat, F., Khan, M.K., Abert-Vian, M., Fabiano-Tixier, A-S., and Dangles, O. (2010) Ultrasound-assisted extraction of polyphenols (flavanone glycosides) from orange (Citrus sinensis L.) peel. Food Chemistry, 119, 851–858.

Cheynier, V. and Rigaud, J. (1986) American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 37, 248–252.

Chung, S.L. and Meyers, S.P. (1979) Bioprotein from banana waste. Developments in Industrial Microbiology, 20, 723–731.

Clifford, M.N. (2000) Nature, occurrence and dietary burden. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 80, 1063–1072.

Coll, M.D., Coll, L., Laencine, J., and Tomas-Barberan, F.A. (1998) Recovery of flavanons from wastes of industrially processed lemons. Zeitschrift fϋr Lebensmittel- Unterschung und – Forschung, 206, 404–407.

Cui, Z.W., Sun, L.J., Chen, W., and Sun, D.W. (2008) Preparation of dry honey by microwave-vacuum drying. Journal of Food Engineering, 84, 582–590.

Decareau, R.V. (1985) Microwaves in the Food Processing Industry. Food Science and Technology, A Series of Monographs, Academic Press, Inc., New York.

Delgado-Vargas, F., Jiménez, A.R. and Paredes-López, O. (2000) Natural pigments: carotenoids, anthocyanins, and betalains – characteristics, biosynthesis, processing and stability. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 40, 173–289.

Delgado-Vargas F. and Paredes-López O. (2003) Anthocyanins and betalains. In F. Delgado-Vargas and O. Paredes-Lopez (eds) Natural Colorants for Food and Nutraceutical Uses, CRC Press, Boca Raton, pp. 167–219.

Earl, R.L. (1969) Unit Operations in Food Engineering, Pegamon Press, Ltd., Great Britain.

Eder A. (2000) Pigments. In Nollet M.L.L. (ed.) Food Analysis by HPLC. Marcel Dekker, New York, pp. 845–880.

Eggum, B.O. (1970) The protein quality of cassava leaves. British Journal Nutrition, 24(3), 761–768.

Elegbede, J.A., Achoba, I.I., and Richard, H. (1995) Nutrient composition of mango (Mangfifera indica L.) seed kernel from Nigeria. Journal of Food Biochemistry, 19, 391–398.

Femenia, A., Garau, M.C., Simal, S., and Rossello, C. (2007) Effect of air-drying temperature on physico-chemical properties of dietary fibre and antioxidant capacity of orange (Citrus aurantium v. Canoneta) by-products. Food Chemistry, 104, 1014–1024.

Giri, S.K. and Prasad, S. (2007) Drying kinetics and rehydration characteristics of microwave-vacuum and convective hot-air dried mushrooms. Journal of Food Engineering, 78, 512–521.

Guo, C., Li, Y., Yang, J., Wei, J., Xu, J., and Cheng, S. (2006) Evaluation of antioxidant properties of pomegranate peel extract in comparison with pomegranate pulp extract. Food Chemistry, 96, 254–260.

Guo, C.J., Yang, J.J., Wei, J.Y., Li, Y.F., Xu, J., and Jiang, Y.G. (2003) Antioxidant activities of peel, pulp and seed fractions of common fruits as determined by FRAP assay. Nutrition Research, 23, 1719–1726.

Harborne, J.B. and Turner, B.L. (1984) Plant Chemosystematics, Academic Press, London, UK.

Harborne, J.B. (1998) Phenolic Compounds in Phytochemical Methods – A Guide to Modern Techniques of plant Analysis, third edition, Chapman & Hall, New York, pp. 66–74.

Hemmerle, H. et al. (1997) Chlorogenic acid and synthetic chlorogenic acid derivatives: Novel inhibitors of hepatic glucose-6-phopshate translocase. Journal of Medical Chemistry, 40, 137.

Heredia, F.J., Francia-Aricha E.M., Rivas-Gonzalo J.C., Vicario I.M., and Santos-Buelga C. (1998) Chromatic characterization of anthocyanins from red grapes - I. pH effect. Food Chemistry, 63, 491–498.

Horbowicz, M., Kosson, R., Grzesiuk, A., and Dębski, H., (2008) Anthocyanins of fruits and vegetables-their occurrence, analysis and role in human nutrition. Vegetable Crops Research Bulletin, 68, 5–22.

Hu, Qing-guo., Zhang, Min., Mujumdar, Arun S., Xiao, Gong-nian, and Sun, Jin-cai. (2006) Drying of edamames by hot air and vacuum microwave combination. Journal of Food Engineering, 77, 977–982.

Jaiswal, V., DerMarderosian, A., and Poter, J.R. (2009) Anthocyanins and polyphenol oxidase from dried arils of pomegranate (Punica granatum L.). Food Chemistry, 118 (1), 11–16.

Ji, X., Avula, B., and Khan, I. A. (2007) Quantitative and qualitative determination of six xanthones in Garcinia mangostana L. by LC–PDA and LC–ESI-MS. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 43, 1270–1276.

Jiang, D.J., Dai, Z., and Li, Y.J. (2004) Pharmacological effects of xanthones as cardiovascular protective agents. Cardiovascular Drug Reviews, 22, 91–102.

John, K.S., Bhat, S.G., and Prasad Rao, U.J.S. (2003) Biochemical characterization of sap (latex) of few Indian mango varieties. Phytochemistry, 62, 13–19.

Juare, L. (1995). Estudio agronomico sobre la utilization de la yucca como forraje. Lima, Estacion Experimental Agricola La Molina. Bol. 58.

Kabuki, T., Nakajima, H., Arai, M., Ueda, S., Kuwabara, Y., and Dosako, S. (2000) Characterization of novel antimicrobial compounds from Mango (Maginifera indica L.) kernel seeds. Food Chemistry, 47, 71, 61–66.

Kathirvel, K., Naik, K.R., Gariepy, Y., Orsat, V., and Raghavan, G.S.V. (2006) Microwave Drying – A promising alternative for the herb processing industry. Written for presentation at the CSBE/SCGAB 2006 Annual Conference Edmonton Alberta, 16–19 July, 2006. The Canadian Society for Bioengineering.

Katsube, T., Tsurunaga, Y., Sugiyama, M., Furuno, T., and Yamasaki, Y. (2009) Effect of air-drying temperature on antioxidant capacity and stability of polyphenolic compounds in mulberry (Morus alba L.) leaves. Food Chemistry, 113, 964–969.

Knapp, F.F. and Nicholas, H.J. (1969) Sterols and triterpenes of banana peel. Phytochemistry, 8(1), 207–214.

Krishna, C. (1999) Production of bacterial celluloses by solid state bioprocessing of banana wastes. Bioresource Technology, 69, 231–239.

Krishna, C. and Chandrasekaran, M. (1996) Banana waste as substrate for alpha-amylase production by Bacillus subtilis (CBTK106) under solid-state fermentation. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 46, 106–111.

Kumar, D.G.P, Hebbar, H.U., Sukumar, D., and Ramesh, M.N. (2005) Infrared and hot-air drying of onions. Journal of Food Engineering, 29, 132–150.

Kroon, P. et al. (1997) Release of covalently bound freulic acid from fiber in the human colon. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 45, 661.

Lancaster, J.E. (1992) Regulation of skin color in apples. CRC Critical Review Plant Science, 10, 487–502.

Lancaster P.A. and Brook, J.E. (1983) Cassava leaves as human food. Economic Botany, 37, 331–348.

Larrauri, J.A. (1999) New approaches in the preparation of high dietary fiber powders from fruit by-products. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 10, 3–8.

Larrauri, J.A., Ruperez, P., and Saura-Calixto, F. (1997) Mango peels with high antioxidant activity. Zeitschrift fϋr Lebensmittel- Unterschung und – Forschung, 205, 39–42.

Larrauri, J.A., Rupereze, P., Borroto, B., and Saura-Calixto, F. (1996) Mango peels as a new topical fibre: Preparation and characterization. Lebensmittel-Wiseenchaft und- Technologie, 29, 729–733.

Lempereur, I., Rouau, X., and Abecassis, J. (1997) Genetic and agronomic variation in arabionoxylan and ferulic acid contents of durum wheat (Triticum durum L.) grain and its milling fractions, Journal of Cereal Science, 25, 103.

Lowe, E.D. and Buckmaster, D.R. (1995) Dewatering makes big difference in compost strategies. Biocycle, 36, 78–82.

Lu, Y. and Foo, L.Y. (1997) Identification and quantification of major polyphenols in apple pomace. Food Chemistry, 59, 187–194.

Lu, Y. and Foo, l.Y. (1998). Constitution of some chemical components of apple seed. Food Chemistry, 61, 29–33.

Lu, Y. and Foo, L.Y. (1999) The polyphenol constitutents of grape pomace. Food Chemistry, 65, 1–8.

Lu, Y. and Foo, L.Y. (2000) Antioxidant and radical scavenging activities of polyphenols from apple pomace, Food Chemistry, 68, 81–85.

Marona H., Pekala E., Filipek B., Maciag D., and Sznelar E. (2001) Pharmacologicalproperties of some aminoalkanolic deverivatives of xanthone. Pharmaxie, 56, 567–572.

Maskan, Medini (2001) Drying, shrinkage and rehydration characteristics of kiwifruits during hot air and microwave drying. Journal of Food Engineering, 48, 177–182.

Mazza, G. and Miniati, E. (1993) Anthocyanins in Fruits, Vegetables, and Grains, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Mouly, P.P., Arzouyan, C.R., Gaydou, E.M., and Estienne, J.M. (1994) Differentiation of citrus juices by factorial discriminant analysis using liquid chromatography of flavones glycosides. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, 42, 70–79.

Madhavi, D.L., Deshpande, S.S., and Salunkhe, D.K. (1996) Food Antioxidants: Technological, Toxicological, and Health Perspectives, Marcel Dekker, Inc., New York.

Manach, C., Mazur, A., and Scalbert, A. (2005a) Polyphenols and prevention of cardiovascular diseases. Current Opinions in Lipidology, 16, 77–84.

Manach, C., Williamson, G., Morand, C., Scalbert, A., and Remesy, C. (2005b) Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. I. Review of 97 bioavailability studies. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 81(suppl), 230S–242S.

Murakami, Shinichi (2003) Mulberry leaves powder manufacturing method. Freepatentsonline. http://www.freepatentsonline.com/6536689.html.

Naczk, M., and Shahidi, F. (2006) Phenolics in cereals, fruits and vegetables: Occurrence, extraction and analysis. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis, 41, 1523–1542.

Niamnuy, C. and Devahastin, S. (2005) Drying kinetics and quality of coconut dried in a fluidized bed dryer. Journal of Food Engineering, 66, 267–271.

Nurgel, C. and Canbas, A. (1998) Production of tartaric acid from pomace of some Anatolian grape cultivars. American Journal of Enology and Viticulture, 49, 95–99.

Ozaki, Y., Miyake, M., Inaba, N., Ayano, S., Ifuku, Y., and Hasegawa, S. (2000) Limnoid glucosides of sastuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu Marcov.) and its processing products. In M.A. Berhow, S. Hasegawa, and G.D. Manners (eds) Citrus Limnoids: Functional Chemicals in Agriculture and Food, ACS Symposium Series 758, Washington DC, pp. 107–119.

O’Riordan, D., Harbourne, N., Marete, E., and Jacquier, J.C. (2009) Effect of drying methods on the phenolic constituents of meadowsweet (Filipendula ulmaria) and willow (Salix alba). LWT – Food Science and Technology, 42, 1468–1473.

Pan, X., Niu, G., and Liu, H. (2003) Microwave-assisted extraction of tea polyphenols and tea caffeine from green tea leaves. Chemical Engineering and Processing, 42, 129–133.

Paul.W. and Riechel, T.L. (1998) High molecular weight plant polyphenolics (tannins) as antioxidants. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry,46, 1887–1892.

Palakajornsak, Y. (2004) Extraction and stability if anthocyanins from mangosteenpeel, Thesis, Silpakorn University, Thailand, p. 103.

Proestos, C. and Komaitis, M. (2008) Application of microwave-assisted extraction to the fast extraction of plant phenolic compounds. LWT – Food Science and Technology, 41, 652.

Prabhanjan, D.G., Ramaswamy, H.S., and Raghava, G.S. (1995) Microwave-assisted convective air drying of thin layer carrots. Journal of Food Engineering, 25, 283–293.

Puravankara, D., Boghra, V., and Sharma, R.S. (2000) Effect of anti-oxidant principles isolated from mango (Magifera indica L.) seed kernels on oxidative stability of buffalo ghee (butter-fat). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 74, 331–339.

Ravindran, V. (1993) Cassava leaves as Animal Feed: Potential and Limitations. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 61, 141–150.

Ravindran V., Kornegay, E.T., Webb, K.E., and Rajaguru, A.S.B. (1982) Nutrient characterization of some feed stuffs of Sri Lanka. Journal of the National Agriculture Society of Ceylon, 19, 19–32.

Renard, C.M.C.G., Rohou, Y., Hubert, C., della Valle, G., Thibault, F., and Savina, J.P. (1997) Bleaching of apple pomace by hydrogen peroxide in alkaline conditions: Optimization and characterization of the products. Lebensmittel-Wissenschaft und-Technologie, 30, 398–405.

Robichaud J. L. and Noble A. C. (1990) Astringency and bitterness of selected phenolics in wine. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 53(3), 343–352.

Roger D.J. (1959) Cassava leaves protein. Economic Botany, 13, 261–263.

Rogers D.J. and Milner, M. (1963) Amino acid profile of manioc leaf protein, in relation to nutritive value. Economic Botany, 17, 211–216.

Sato M., Maulik G., Ray P.S., Bagchi D., and Das D.K. (1999) Cardioprotective effects of grape seed proanthocyanidin againstischemic reperfusion injury. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, 32, 1289–1297.

Sharma, G.P. and Prasad, S. (2001) Drying of garlic (Allium sativum) cloves by microwave-hot air combination. Journal of Food Engineering, 50, 99–105.

Souquet, J.M., Cheynier, V., Brossaud, F., and Moutounet, M. (1996) Polymeric proanthocyanidins from grape skins. Phytochemistry, 43, 509–512.

Souquet, J.M., Labarbae, B., Le Guernevé, Cheynier, V., and Moutounet, M. (2000) Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, 48, 1076–1080.

Soysal, Y. (2004) Microwave drying characteristics of parsley. Biosystems Engineering, 89(2), 167–173.

Sreenath, H.K., Carndall, P.G., and Baker, R.A. (1995) Utilization of citrus by-products and wastes as beverage clouding agents. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering, 80, 190–194.

Samman, S., Lyons Wall, P.M., and Cook, N.C. (1998) Flavonoids and coronary heart disease: Dietary perspectives. In C.A. Rice Evans and L. Packer (eds) Flavonoids in Health and Diseases, Marcel & Dekker, USA, pp. 469–482.

Schieber, A., Stintzing, F.C., and Carle, R. (2001) By-products of plant food processing as a source of functional compounds-recent developments. Trends in Food Science and Technology, 12, 401–413.

Sharma, S.K. and Maguer, M.L. (1996) Lycopene in tomatoes and tomato pulp fractions. Italian Journal of Food Science, 2, 107–113.

Samman, S., Sandstrom, B., Toft, B., Bukhave, K., Jensen, M., Srensen, S., et al. (2001) Green tea or rosemary extract added to foods reduces nonheme-iron absorption. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 73, 607–612.

Soji, T., Yanagida, A., and Kanda, T. (1999) Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, 47, 2885–2890.

Someya S., Yoshiki Y., and Okubo, K. (2002) Antioxidant compounds from bananas (Musa Cavendish). Food Chemistry, 79(3), 351–354.

Sultanbawa, M.U.S. (1980) Xanthonoids of tropical plants. Tetrahedron, 36, 1465–1506.

Subagio, A., Morita, N., and Sawada, S. (1996) Carotenoids and their fatty-acid esters in banana peel. Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology, 42(6), 553–566.

Tasirin, S.M., Kamarudin, S.K., Jaafar, K., and Lee, K.F. (2006) The drying kinetics of bird’s chilies in a fluidized bed dryer. Journal of Food Engineering, 79, 2, 695–705.

Tewari, H.K., Marwaha, S.S., and Rupal, K. (1986) Ethanol from banana peels. Agriculture Wastes, 16, 135–146.

Torres, J.L. and Bobet, R. (2001) New flavanol derivatives from grape byproducts. Antioxidant aminiethylthio-flavan-3-ol-conjugats from a polymeric waste fraction used as a source of flavanols. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, 49, 4627–4634.

Vega-Gálvez, A., Di Scala, K., Rodriguez, K., Lemus-Mondaca, R., Miranda, M., and Lopez, J. (2009) Effect of air-drying temperature on physico-chemical properties, antioxidant capacity, colour and total phenolic content of red pepper (Capsicum annuum, L. var. Hungarian). Food Chemistry, 47, 647–653.

Vergara-Valencia, N., Granados-Perez, E., Agama-Acevedo, E., Tovar, T., Ruales, J., and Bello-Perez, L.A. (2007) Fibre concentrate from mango fruit: Characteriziation, associated antioxidant capacity and application as a bakery product ingredient. LWT – Food Science and Technology, 40, 722–729.

Venir, E., Torre, M.D., Stecchini, M.L., Maltini, E., and Nardo, P.D. (2007) Preparation of freeze-dried yoghurt as a space food. Journal of Food Engineering, 80, 402–407.

Walker, E.B. (2007) HPLC analysis of selected xanthones in mangosteen fruit. Journal of Separation Science, 30, 1229–1234.

Yapo, B.M. and Koffi, K.L. (2008) Dietary fiber components in yellow passion fruit rind: A potential fiber source. Journal of Agriculture and Food Chemistry, 56, 5880–5883.

Yeoh, H.H. and M.Y. Chew (1976) Protein content and amino acid composition of cassava leaf. Phytochemistry, 15, 1597–1599.

Yongsawatdigul, J. and Gunasekaran, S. (1996) Microwave-vacuum drying of cranberries: Part I. Energy use and efficiency. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation, 20, 121–143.

Zhanga, X. et al. (2009) Optimized microwave-assisted extraction of phenolic acids from citrus mandarin peels and evaluation of antioxidant activity in vitro. Separation and Purification Technology, 70, 63–70.