A Field Guide to Flirting

John and Jane were on their second drinks. So far, neither of them had spoken a word to each other. And yet silent come-and-get-me signals were flying back and forth between them. Jane fiddled with her hair. John fidgeted with the straw in his drink. Jane hiked up her skirt, scratching an imaginary itch on her thigh. John stretched, puffing out his chest. Jane looked at John, but when John looked back, she looked away, then the game of eye tag repeated itself in reverse. Jane was getting frustrated. What was taking John so long to take the hint? Was his interest in her purely a figment of her imagination?

John was also wondering whether the signals coming from Jane’s direction were just his own wishful thinking. He’d misread women before, and hated being shot down, so he sat and waited, praying for a clear sign. As if on cue, Jane walked up to the bar, put her hand on John’s arm so that she could scoot by him and get the bartender’s attention. “Excuse me,” she apologized to John. “Crowded in here tonight, isn’t it?”

Even then, John was torn. Did that touch mean Jane was merely craving another Stoli and soda, or was that a ploy to break the ice? Was Jane just being friendly, or flirty? To find out, John looked Jane in the eye. This time, when their gazes met, Jane held it for a beat longer than usual and smiled. John smiled back. Finally, it clicked: They’d both been flirting with each other all night.

“Can I buy you a drink?” John asked.

To his relief, Jane accepted.

JANE’S THIGH SCRATCHING, John’s chest puffing … these weren’t random nervous gestures. They were classic cues in the ancient human ritual known as flirting. What are the steps to this subtle dance? And what makes certain people better flirts than others? In the 1980s, Monica Moore, a grad student at the University of Missouri, decided to pin down some answers by hitting countless bars, clubs, and parties to spy on men and women in action.

To blend in with the crowd, Moore dressed the part: dark eyeliner and black attire on Goth night, cowboy boots and jeans on Western night, bed sheet on toga night. To avoid getting hit on herself, Moore typically brought along a male colleague. “We would look like we were on a date,” she says. “Which was great, because single people rarely pay much attention to couples.” Once Moore and her “date” had scoped out the scene, Moore would pick her study subject out of the crowd, sit back, and watch, mumbling her target’s every move into a tiny tape recorder stashed under her clothes. Hair flip … eyebrow flash … head toss … neck presentation … Type I glance … Type II glance … smile … woman approached.

Moore’s first discovery on the front lines of flirting was that human courtship is far more complex than a little eye batting. She cataloged a total of 52 flirtatious tactics. Moore’s second discovery was even more surprising: People who rack up the most attention aren’t the best looking, but the best flirts. On average, someone sending out 35 come-hither cues per hour will be approached by four people during that time period. “I made this discovery one night while watching two women who were flirting pros,” Moore recalls. “They were average-looking, and yet men were approaching them left and right. It proved that being attractive was only part of the equation. What you do with what you’ve got is equally important.”

Sending out a flurry of hair flips and eyebrow arching is only half the battle. The other half is recognizing when someone’s attempting to flirt with you. To the untrained eye, this can be a difficult task, says Timothy Perper, author of Sex Signals, who has clocked 3,000 hours sitting in singles bars, airports, and church socials taking notes on people’s behavior. The majority of men, he found, were essentially blind to the signals women were sending them, which suggests that flirting is a language we would all stand to learn better.

You Lookin’ at Me?

When Yvonne met Henry at a party, she looked into his eyes and saw … something. “I still don’t know what I saw,” she admits. “Henry has beautiful blue eyes, but still, I don’t think that was it. All I know is that the moment we locked gazes seemed to last forever, even though I’m sure it was just a second.”

Yvonne and Henry chatted for a while about what they did for a living (Yvonne was a high school counselor, Henry a contractor) and what they enjoyed doing in Salt Lake City, Utah, where they had both lived since college (they were both ski addicts who hit Snowbird on a regular basis). And yet Yvonne considered all this conversation mere window dressing for whatever it was she saw and felt when she stared into his eyes. And clearly, Henry saw something, too, since he asked for her number and they’ve been dating ever since. “I was never one to believe in love at first sight until that night,” Yvonne says. “I can’t explain it. Did we know each other in a former life? Were we soul mates? I have no idea. All I know is that it was powerful.”

Room encompassing glance (Type I)

Short darting glance (Type II)

Gaze fixate (Type III)

Eyebrow flash (raised eyebrows)

Head toss

Neck presentation (head tilted 45 degrees to the side)

Hair flip

Head nod

Lip lick

Lipstick application

Pout

Smile

Coy smile

Laugh

Giggle

Kiss

Whisper

Face to face (looking straight at someone at a range of approximately 5 cm)

Arm flexion (wrist and elbow bent in toward own body)

Tap

Palm reveal (palm of hand is presented toward target)

Gesticulation

Hand hold

Primp

Hike skirt

Object caress

Caress (face/hair)

Caress (leg)

Caress (torso)

Caress (back)

Buttock pat

Lean forward

Brush (hand placed on someone else while passing by)

Breast touch

Knee touch

Thigh touch

Foot to foot

Placement

Shoulder hug

Hug

Lateral body contact

Frontal body contact

Hang on someone

Parade (walking by with exaggerated hip roll)

Approach

Request dance

Dance (acceptance)

Solitary dance

Point/permission grant (as in “you can sit here”)

Aid solicitation (request for help)

Play (pinching, tickling, or sticking your tongue out)

From Moore, M. (1985). “Nonverbal courtship patterns in women: Context and consequences.” Ethology and Sociobiology 6 (4): 237-47. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

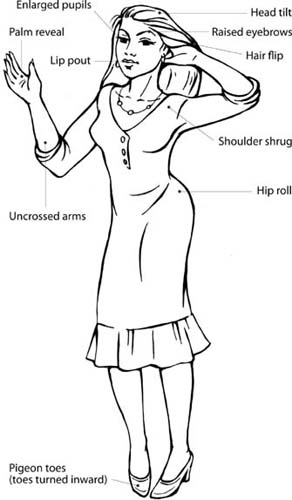

Your head-to-toe guide to flirtatious signals

There’s a reason why scores of people sense the first stirrings of sexual attraction when staring into each other’s eyes. According to MRI scans of people’s brains, eye contact causes an area called the ventral striatum, otherwise known as the reward center, to light up like a slot machine. Essentially, that means we’re wired to interpret someone gazing deep into our eyes as a great pleasure. Eye contact feels so fantastic, in fact, that in experiments where study subjects were shown photos of people staring straight at them in disgust, as well as photos of people with a pleasant expression looking off to the side, the disgusted faces were rated as more appealing than the pleasant ones, all due to a little eye contact.

While established lovers can stare into each other’s eyes for ages, for two strangers straight out of the flirting gates, it’s a much more tentative process. Couples take turns looking at each other for a while until they screw up the courage to meet each other’s gazes head on. Even then, it lasts only two to three seconds on average, although even that will seem like an eternity (in nonromantic situations, people lock eyes for only 1.18 seconds on average). After that point, one party, usually the woman, will look away. The game repeats itself as many times as necessary until someone, usually the guy, gets the hint and starts circling his quarry. Moore, who actually counted the number of look-then-look-away games it took for a guy to pick up on the fact that a woman had laid out the welcome mat, found that just one or even two times usually doesn’t cut it. It took a total of three times before men got the hint.

Once two people get comfortable with each other, longer bouts of eye contact settle in—and some curiously strong feelings ensue. To study the effects of eye contact on intimacy levels, body language experts Allan and Barbara Pease told clients at a dating agency that the person they were being set up with had a lazy eye that could be spotted if they looked closely enough. During the date, this prompted both people to stare into each other’s eyes more often than they usually would—and, as a result, they were four times more likely to meet again than the dating agency average. Stranger still, in another experiment where James Laird at Clark University asked 96 men and women who didn’t know each other to stare into each others’ eyes, stare at each other’s hands, or some combination thereof (she stares at his hands and he at her eyes, for example), those who’d engaged in a mutual gaze confessed to feelings of “passionate love” for one another. In another study where Arthur Aron at Stony Brook University New York asked men and women to stare into each others’ eyes for four minutes, they also admitted that they felt unusually attracted to each other. Six months later, rumor has it that two of these study subjects got married.

Eye contact is such a powerful force, it has even produced its own version of speed dating called speed gazing, where participants spend three minutes with a variety of romantic prospects, but the catch is, you can’t talk. All you do is stare into each others’ eyes. At first, many speed gazers can’t help but giggle, fidget, or make faces to break the tension. By the end, though, once the staring contests are wrapped up and participants are allowed to mingle, their conversations are often much more profound as a result. As Ryan Parks, a twenty-six-year-old hedge fund research analyst described the questions that the eye gazing sparked: “Why are you sad? Why are you optimistic? You start asking yourself all these deep questions about the person you’re looking at,” he told the New York Times. “They’re all so much better than the dumb questions of normal small talk.”

My, What Large Pupils You Have

Centuries ago, prostitutes used eye drops containing belladonna, a plant tincture containing atrophine, to enlarge their pupils and appear more attractive to clients. Unfortunately, prolonged use led to vision problems and even blindness.

Another reason why we love eye contact may boil down to the clues contained in someone’s eyes—like the pupils. One night in bed, as psychologist Eckhard Hess at the University of Chicago watched his wife read a book, he noticed that her pupils grew and shrank in size as she poured over certain passages. Since then, studies of pupillometry have shown that our pupils constrict to pinholes when looking at photos of politicians we hate, widen a little when looking at photos of politicians we like, and widen further if the person in the photo is naked (thankfully, researchers didn’t test the effects of viewing naked politicians). Enlarged pupils not only signal we like what we see, but prompt people to like us back. Like tiny black holes, pupils draw people in, as researchers found out by administering a drug to study subjects that artificially widened their pupils for a while. Set loose among a larger group of volunteers who were then asked to pick a partner to work with on an experiment, the people with bigger pupils were picked far more often than the rest. Our love of large pupils may explain why many people find blue and green eyes more attractive than brown ones, since on these lighter backgrounds, pupil dilation is easier to see.

What the iris reveals. The colored part of the eye often contains crypts (discolored depressions) and furrows (curving lines around the outer edge) that are correlated to certain personality traits. People with crypts are more likely to be friendly and affectionate; people with furrows are more likely to be spontaneous and hedonistic.

From Larsson, Mats, Nancy L. Pedersen, and Håkan Stattin (2007). “Associations between iris characteristics and personality in adulthood.” Biological Psychology 75: 165-75. Reprinted with permission from Elsevier.

Whatever eye color is your favorite, that little Lifesaver of color surrounding the pupils also contains clues to compatibility. That’s because the iris contains crypts (discolored depressions) and furrows (curving lines around the outer edge). Crypts and furrows form due to irregularities in the density of cells in the iris, and may contain clues to whether someone’s worth flirting with. In 2007, Swedish psychologist Mats Larsson examined the eyes of 428 college students and counted the number of crypts and furrows in each set. He also gave his study subjects personality tests. He found that people whose irises contain a lot of crypts were more likely to be warm, tender, and trusting. People with a high number of furrows were more likely to be impulsive and prone to indulge their cravings. The more crypts and furrows, in other words, the better—at least, if you want to be bantering with someone who’s tender, warm, trusting, impulsive, and prone to enjoy the good things in life.

Why Men Talk to Women’s Breasts

Ever notice how a man’s gaze tends to wander over a woman’s anatomy mid-conversation? Believe it or not, studies show that women also eyeball a guy’s goods, even more often than men do theirs. The reason guys don’t catch women looking has to do with variations in each gender’s powers of peripheral vision. Typically, “women’s peripheral vision extends to at least forty-five degrees to each side, above and below, which means she can appear to be looking at someone’s face, while, at the same time, she is inspecting the goods,” Alan and Barbara Pease write in their book The Definitive Book of Body Language. Meanwhile, men’s peripheral vision is much narrower in scope—which is great for spotting targets far in front of them (hello, hunting), but not so great when you’re trying to sneak a peak at something hovering along the outskirts. To illustrate the peripheral vision discrepancy between men and women in the most obvious way possible, the Peases accompanied a group of men and women on their first field trip to a nudist colony. As visitors frolicked with the locals, the Peases’ videotapes of their interactions clearly showed the men staring agog at people’s privates, even though the men swore up and down they tried to do so in secret. Women, meanwhile, claimed they were constantly sneaking peaks but never once looked like they were.

So, Um, Come Here Often?

“Is your daddy a thief?” “Did it hurt when you fell from heaven?” “Is that dress felt? Would you like it to be?” With lines like these out there, no wonder most people hate pickup lines. Still, to begin seducing someone, the conversation needs to start somewhere. Michael Cunningham at the University of Louisville gave his students a mission: Get out there and start hitting on people. Cunningham provided them with an array of canned come-ons that fell into one of three categories: direct, innocuous, and cute/flippant. Direct approaches, it turns out, were most successful. The opener “I feel a little embarrassed about this, but I’d like to meet you” scored highest with an 82 percent success rate (“success” was defined as the recipient being willing to continue the conversation). The innocuous approach came in second, with the line “What do you think of the band?” scoring 70 percent. Even a simple “Hi” scored 55 percent. Meanwhile, cute-flippant gambits bombed badly. “Bet I can out-drink you” only got the conversation rolling 20 percent of the time, “You remind me of someone I used to date” only 18 percent. Not surprisingly, really cornball openers—e.g., “I may not be Fred Flintstone, but I can make your bed rock!”—might seem hilarious to your friends, but when uttered to complete strangers, they’re so not funny, and should be avoided at all costs. The above results apply to men hitting on women; women, on the other hand, got a positive response from men 80 percent of the time no matter what opening line they used.

If the direct approach is too scary, consider these alternatives, tested by Christopher Bale at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. Suitors will fare well if they use opening lines that offer help (“Want me to carry that for you?”), ask for help (“Could you help me pick out a gift for a friend?”), or display intelligence (“It amazes me that Van Gogh painted this at Saint-Rémy”). Women hitting on men are better off taking a direct approach. “Since we’re both sitting alone, would you care to join me?,” “I’d really like to get to know you,” and even a classic “Hi” made it into men’s top-five favorite overtures from women.

As flirters continue talking, they can solidify their bond by seeking out common interests (“You ski? I ski! What a coincidence!”), although that doesn’t mean you should bask in your similarities nonstop. In one study at the University of Oklahoma where pairs of participants were told to talk about certain topics, those who agreed with their partner 100 percent of the time were found to be less likeable than those who disagreed at the outset, then later yielded to the other person’s opinion. Putting up a fight at first can also work wonders with compliments, as researchers at the University of California in Santa Cruz found out when conducting a study where participants were able to “overhear” what other participants were saying about them. In certain cases, the comments were positive from beginning to end. In other cases, the comments started out negative but became positive over time. Afterward, when these study subjects were asked to evaluate the people they had overheard, they preferred those who trashed them then turned nice over the ones who had gushed constant accolades.

Tongue Tied?

Top Ways to Break the Ice

| Type of line |

Percent rating line as good or excellent |

| ———————————————————————— | |

Adapted from Kleinke, C. L, F. B. Meeker, R. A. Staneski (1986). “Preference for opening lines: Comparing ratings by men and women.” Sex Roles 15 (11/12): 585-600. Reproduced with kind permission of Springer Science and Business Media. There are instances where we have been unable to trace or contact the copyright holder. If notified, the publisher will be pleased to rectify any errors or omissions at the earliest opportunity.

Whatever you say, the way you say it is also important. Alex Pentland at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology analyzed nearly 60 speed-dating conversations. Instead of focusing on the content, Pentland examined the tone, pitch, pacing, number of interruptions, and length of time spent talking by each party. Pentland found patterns that could help him predict with 75 percent accuracy who was attracted to whom. One factor important in women was pitch. The more a woman varied the pitch of her voice, the more attractive she appeared to potential prospects. Another important factor for men and women was the number of short interjections such as “I see” or “go on” peppered in the conversation. Some people used as many as thirty interjections in five minutes, others as few as five. And while grunting “wow” or “uh huh” might not sound all that impressive, it’s actually more impressive than a soliloquy you might be tempted to trot out about finishing med school or crossing the Sahara on camelback. Interjections encourage others to trot out their own stories, which makes you something even better than a great talker: a good listener.

“He Gave Good Text”

Flirting need not even occur face-to-face, as millions of online daters can attest to after having exchanged a flurry of friendly e-mails and text messages before even meeting for coffee. This can create a sense of “virtual intimacy,” says Paige Padgett, a researcher at the division of epidemiology and disease control at the University of Texas School of Public Health. This may explain why, in her study, nearly one third of online daters end up having sex on their very first date. In comparison, only 15.1 percent of people in a nationwide sample have had sex with someone they’ve known for only a day or two.

Conversation can be so telling, Pentland and his colleagues have developed a software for cell phones that, based on the number of interjections tallied on the other end of the line, reveals whether someone is hanging on your every word or only half listening. Called the Jerk-O-Meter, this software is not yet commercially available, so for the meantime you’ll just have to listen closely and perform your own mental calculations. Are your comments met with exclamations such as “No way!,” or with dead air? Keep tabs, and you’ll soon know if you should carry on or stop calling—permanently.

The Mona Lisa Effect

Which person would you be more likely to sleep with if they made the following statements:

Person #1: “I really enjoy helping people.”

Person #2: “Old people bore me and I find children irritating.”

Person #1 is the more appealing partner any day, right? Andrew Clark at the University of Bristol in England begs to differ. In 2007, he showed animated line drawings of faces to study subjects, asking which face they found most attractive. He also dubbed in prosocial and antisocial statements. When offensive declarations were paired with smiles, raised eyebrows, and other positive facial expressions, viewers rated these faces as more attractive than those drawings that didn’t smile but made more admirable statements. Clark’s conclusion: What we say doesn’t matter all that much, provided we smile when we say it.

In flirting parlance, all smiles are good. But certain smiles— and humans have eighteen types total—are better than others. Scientists who know this owe thanks to French neurologist Guillaume Duchenne, who began experimenting with heads acquired from the French guillotine. These heads, though dead, still responded to electrical impulses, which allowed Duchenne to jolt certain facial muscles and see which expressions ensued.

One day while tinkering with his heads, Duchenne discovered that smiles were controlled by two distinct sets of muscles. The first set, the zygomatic major muscles, pull the corners of the mouth back in a U-shaped grin. The second set, the orbicularis oculi, make the eyes squint and cause crow’s feet. Duchenne also found that the zygomatic majors are linked to our voluntary nervous system and, as a result, can be consciously willed to whip up a fake smile when a situation calls for one (like when we say “cheese” to a photographer). The orbicularis oculi muscles, however, are linked to our autonomic nervous system and aren’t under our conscious control; they’ll only react when we’re genuinely happy. Why should you care which nerves are connected to what? Because if you’re wondering whether that smile someone’s giving you is for real, check for crinkling around the eyes. If it’s there, this person’s truly glad to see you. If not, you’re just being tolerated until your victim can plan an escape.

Which smile is real? The smile on the left is fake, but the one on the right is genuine because of the squinting around the eyes, which is a muscular reaction beyond our conscious control.

If, on the other hand, your friendly entreaties are being greeted with a poker face, consider stepping up to the plate and smiling yourself. Smiles are contagious. In one Swedish study, neurologist Ulf Dimberg hooked up people’s faces (live ones, not guillotine castoffs) to equipment that detects subtle electric signals from muscle fibers. Then, Dimberg showed his subjects photos of happy and angry faces, simultaneously instructing his subjects to smile or frown at what they saw. Occasionally, Dimberg instructed them to smile at photos of frowning faces, or frown at photos of smiling faces. Easy, right? And yet, the electric signals coming from their facial muscles told a different story. No matter what Dimberg said, when faced with a smiler, facial muscles automatically twitched upward to smile in kind. When faced with a frowner, the mouth crept downward. Our natural impulse is to mirror what we see, so try a smile when you want someone to smile back.

Laughter: The Best Medicine?

No flirtatious exchange would feel complete without lots of laughter in the mix. But surprisingly, most laughter occurs when nothing funny is said. Robert Provine, a professor at the University of Maryland and author of Laughter: A Scientific Investigation, knows this all too well. He and a team of researchers skulked around campus surreptitiously listening in on students’ conversations, recording what prompted a giggle. A full 1,200 “laugh episodes” later, Provine found that only 15 percent of laughter is generated by anything remotely recognizable as a punch line. The majority of laughter followed surprisingly mundane statements, such as “May I join you?” or “It was nice meeting you.”

Why do we laugh when nothing’s funny? According to Provine, it’s to bond with others. That’s why we’re thirty times more likely to laugh around company verses when we’re alone. Even nitrous oxide, or laughing gas, triggers few giggles when taken in solitude. Jane Warren and Sophie Scott at the University College in London performed MRI scans of people’s brains while they listened to audio recordings of laughter as well as upsetting sounds like screaming and retching. The laugh tracks activated the brain’s pre-motor cortical region, which, in turn, triggered the muscles of the face to crinkle in their own fit of chuckles. When we hear someone laugh, we’re programmed to laugh right along with them (and thankfully, this copycat tendency doesn’t hold true when we hear people screaming or retching).

Any laughter is good laughter when you’re trying to spread the love, but laughter about funny stuff is best—which makes having a sense of humor a major asset. According to Eric Bressler at McMasters University, each gender defines a sense of humor differently. To a woman, a man with a sense of humor is someone who “produces” humor (i.e., jokes). To a man, a woman with a sense of humor is someone who “appreciates” humor (translation: She laughs at his jokes). Bressler found that men like women who “produce” humor as pals, but this wasn’t an important factor when picking women to date. The reason may lie in how men use humor: as a means to mock other men. Putdowns are par for the course in male circles, as was proved in an experiment where Sam Shuster, a professor at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital in England, rode a unicycle through town and tallied the comments he received. Women were encouraging. Men shot snide remarks like “Lost your wheel?” Given men wield humor as a weapon, it’s understandable they’d be leery of taking a comedian to bed. What if she turns his penis or some other personal foible into the butt of her next joke?

The ABCs of Body Language

“We’ve got to get out of here—now.”

David Givens was in a van, parked in the southeast section of Seattle, Washington. He and a wildlife photographer had been surreptitiously snapping pictures of a group of people at a bus stop. It was a rough section of town, and while Givens and his cameraman tried to maintain a low profile, clearly a few of the men they’d been observing through a telephoto lens had caught on, and weren’t too happy about it. As the men started toward the van, Givens scrambled for the keys and peeled off. “Studying human courtship behavior in their natural habitat can be a dangerous profession,” he admits. “It’s like watching wildlife. If a rhino charges, you’d better have the key in your ignition for a quick getaway.”

Givens has spied on people flirting in a variety of venues, from bus stops to bars, airplanes to college cafeterias. Jotting down notes in a leatherbound notebook, he rarely listens in on what people are saying. In studies examining videotapes of people conversing about their feelings and attitudes on a variety of topics, researchers have found that only 7 percent of what we mean is based on what we say. Another 38 percent is based on how we say it. The rest—by far the majority at 55 percent—is based on an entirely different language. Body language, of course.

Every part of our bodies, from head to toe, speaks volumes about our interest levels. Among the easiest to spot immediately, Givens says, are someone’s hands. The phrase “talk with your hands” exists for a reason. In particular, take note of whether the palms are facing upward or downward as they move around or rest on the table. Palms up is a sign that someone has nothing to hide, a way to say See? I’m not holding a rock, Mace, or anything else that will hurt you. Palm-down gestures, on the other hand, are a sign of dominance. Think back to how your grade school teachers would attempt to calm unruly students by patting the air palm-down in front of them (not that it worked, but hey, they tried). Generally, dominance is not something you want to display in any kind of seduction scenario, although men may occasionally direct a gesture of dominance (from palm-down air-patting to chest-puffing) toward nearby rivals to say I’ve got dibs—go hit on someone else.

Clearly, arms crossed over the body are a way to say Back off, bud, but not all arm barriers are easy to see. People sitting at a table facing you, for instance, might erect their deadly force field a bit farther out. For an easy tip-off, check where they’ve placed their coffee cup, martini, or water glass. If the cup is on the right and they’re right-handed, then you’re barrier-free. If the cup’s on their left, that means they’ll have to reach across their body to grab it, perhaps even leaning their elbow on the table and using their forearm to form a more permanent blockade. To the average observer, it’s just two people having coffee. Look closer, and you’ll see two people with zero chance of sharing a bed later. On the bright side, if you see a shoulder shrug, you’re getting warmer. This bashful, aw-shucks gesture is known among biologists as the “cute response,” and crops up unconsciously when we meet babies or puppies. In a seduction scenario, the shoulder shrug says basically the same thing: Let’s cuddle.

Which woman is open to your advances? If someone’s drink is placed so that her arm has to reach across the table to grab it, that’s a hidden arm cross— a protective maneuver which signals she’s not all that into you. If her drink is placed on the same side of the table as the hand she uses to grab it, that’s open stance—and a sign she might want to get closer.

While staring at someone’s feet may not be the wisest move soon after having met someone, if you glance down occasionally you might get a glimpse of what may be the most reliable indicator of which way the wind is blowing. The farther away a body part is from our brain, the less aware we are of what it’s doing. Most people are aware of their facial expressions and can fake them when necessary, which can come in handy when you want to look thrilled opening a gift from Grandma that turns out to be yet another ugly sweater. Down below, though, the feet dance to their own drummer. Generally, they’ll point in the direction we most want to go. If someone’s feet are pointed toward you, that’s good. If they’re pointed away from you, that’s bad. If they’re pointed toward the door, that means they really want to get the hell out of there. If the toes are pointed in toward each other? While these so-called “pigeon toes” might not seem like a very sexy gesture, feet arranged this way reveal a subconscious attempt to shrink in size and say I’m harmless. I’m helpless. Take me home.

Legs can also talk, especially when someone’s sitting so the limbs are free to roam. Legs spread open convey dominance and openness, while crossed legs convey submissiveness or defensiveness. Crossed legs where you rest an ankle on the knee can be the best of both worlds. This posture is dominant, and yet relaxed. Cavalier, but in control. This pose is especially common among Americans, which is why it’s been nicknamed the “American Figure Four.” (In World War II, Nazis were told to keep an eye out for people sitting this way, since chances were high it was an American spy.) Crossed ankles, whether standing or sitting, are the mental equivalent of biting one’s lip. They’re a sign someone’s holding back opinions, whether about your silly sideburns or your suggestion to see the movie Beverly Hills Chihuahua. So if you spot an ankle lock, it might be worth asking, “Is something bothering you?” Your perceptiveness may glean some brownie points and allow you to redeem yourself.

Body language doesn’t just communicate how we’re feeling or whom we’d like to take home with us. It can also brag—by flaunting our assets. That’s why women will fiddle with and flip their hair even if it’s short and doesn’t need flipping, tilt their heads to expose their necks, walk with that boom-chiga strut to accentuate their curvy hips, and lick their lips—which, supposedly, remind men of another set of lips. Meanwhile, guys stretch or stick their hands in their pockets, which conveniently broadens their chest into a wedge shape that says I am man, hear me roar. If those pocketed hands are situated so that the thumbs are visible and pointing inward, that’s called a “crotch display,” which serves to draw our eyes to the prize. Crotch displays are pronounced among other primates as well. Dominant baboons will all but parade their penises before onlookers, fondling them constantly to remind everyone that yes, they really are all that. Human males also engage in “crotch adjustments,” although usually on a more subtle level.

You Can Flirt Where?!

Flirting is so natural an impulse we don’t reserve all our efforts for Happy Hour. A full 62 percent of drivers say they’ve flirted with someone in a different vehicle during their morning commute, and 31 percent of those flirtations have resulted in a date (thus the success of Flirtingintraffic.com, a Web site on which you can purchase a sticker with a unique ID, which drivers can jot down when they see you and send you a message via the Web site).

In the same way that people search for things they have in common during conversation, we also seek out common ground through body language, a practice known as isopraxism, or the chameleon effect. To a certain extent, this happens naturally, as Tanya Chartrand and John Bargh at New York University found when they enlisted volunteers to complete a task paired up with research assistants who had been instructed to either shake their foot or rub their face throughout the interaction. By the end of their ten-minute session, videotapes showed that the volunteers were also shaking their feet and rubbing their faces in a subconscious attempt to get in sync with their partner. Next, Chartrand and Bargh turned the tables and instructed their assistants to mimic the movements of volunteers they were paired with. Afterward, volunteers who had been aped reported liking their partners much more than volunteers whose partners made no effort to mirror their actions.

Getting In the Zone

Givens was on an airplane, observing flirting unfold at 40,000 feet. Saturday, p.m. November 23—Aboard Southwest Airlines flight 358, Oakland to San Diego, he jotted down in his leather notebook. In the row in front of him, a man and woman had just taken their seats in 11D and 11E and buckled their seat belts. Givens couldn’t see much in terms of their facial expressions, but he didn’t have to. Even the backs of their bodies were communicating plenty.

“What do you do?” the man asked the woman, leaning toward her.

“I work in real estate,” the woman replied, leaning back— and farther away—from her friendly seat mate. Realizing he’d crossed some invisible threshold and made her uncomfortable, the man straightened his posture. Only after a drink, more conversation, and some flirtatious hair-fiddling on her part did he again venture closer. This time, she did not lean away. This time, Givens noted, she had allowed him into her personal space.

Whether you realize it or not, there’s a bubble of air surrounding you that you consider your space. For most Americans, this “intimate zone” extends for eighteen inches around your body. Only your closest allies—spouses, lovers, children, pets—are allowed past this invisible barrier. Beyond that, from eighteen to forty-eight inches out, lies the “personal zone,” which is the area we reserve for acquaintances at cocktail parties. From four to twelve feet out lies the “social zone,” reserved for your postman, plumber, and other people you don’t know very well. Anything beyond twelve feet is the “public zone,” where anything goes. These barriers also vary by culture. In Japan, the “intimate zone” extends only eleven inches, which is why the Japanese will often stand too close to Americans, who back off, which in turn prompts the Japanese to take another step closer. When video recordings of Japanese and American businessmen are played at high speed, it often looks as if duos are waltzing around the room.

A map of the invisible barriers we have around our bodies, and whom we’re comfortable allowing in each area.

Chances are, you and potential paramours will meet and mingle in each other’s “personal zones,” hovering eighteen to forty-eight inches within each other’s orbits. Getting intimate involves breaking into their “intimate zone.” Do it too soon, however, and you’re bound to make them uncomfortable. Find an excuse to step briefly into someone’s intimate zone-to allow someone behind you to pass or grab an appetizer off a wandering tray—then step back out again. If that person is drawn to you, he or she will respond by stepping in closer after you’ve backed off. Once that happens, you’re ready to get even closer. How? Through touch.

At first, most people will reach out and touch … themselves. It’s called “self-grooming.” They stroke their own neck, or rub their own knee, since what they really want to do is stroke your neck or knee. Eventually, people will tentatively try grooming each other, an activity called “lint-picking.” She whisks an imaginary speck from his lapel. He brushes a crumb from her sweater.

One option is to head for the elbow. This pointy appendage is so used to getting jostled, a tap from you will seem friendly but not too friendly. Give it a try, and feelings of good will may start magically moving in your direction. In one experiment, a team of researchers led by Joel Brockner at Tufts University placed a dime on the ledge of a telephone booth, then waited for unsuspecting subjects to walk in and find it. At this point, a researcher approached and asked, “Did you happen to see my coin in that phone booth?” On average, 66 percent of people returned the coin. And yet when the researcher’s question was accompanied by a light touch on the stranger’s arm, 78 percent returned the dime.

Lay on the eye contact. Start out with what’s called a Type I glance (your eye sweeps the room, passing by your prospect), then move on to a Type II glance (short, darting glance), then a Type III (you hold someone’s gaze for a second then look away). The longer you can look, the stronger your feelings may grow for each other—provided, of course, that all that eye contact is mutual. Otherwise, staring at someone who’s not staring back will just come off as creepy.

Widen your pupils. The pupils in our eyes dilate when they see something they like; it can also make you look more alluring to others. To take advantage of this fact, pick dimly lit places for your dates, which will force your pupils to dilate so you two can drink each other in.

Separate the real smiles from the fakes. Unsure whether someone’s genuinely overjoyed to see you or has plastered on a fake smile for the sake of being polite? Shift your focus from the mouth to the eyes. If the corners of the eyes are squinting (perhaps you’ll see crow’s feet), then the smile is the real deal. You’re welcome company.

Say something—anything. While you may feel tongue-tied, pretty much anything you say will get the conversation rolling. Just avoid cheesy pickup lines, which will only make you seem insecure. While women often wait for men to break the ice, women who do so are almost guaranteed to get a positive response.

Encourage people to keep talking. During conversation, try to sprinkle in around six short interjections per minute, such as “I see,” “Go on,” “Interesting,” or “What happened next?” This indicates that you’re interested in what someone is saying, which encourages people to open up and will encourage bonding.

Mirror your date’s movements. If he crosses his legs, cross yours. If she takes a sip of her drink, do the same. This will convey that you two are on the same wavelength, further enhancing rapport. One caveat: Don’t be so obvious about it that you get caught having to explain why you two just happen to be scratching your left ear at the very same time. That would be weird.

Keep an eye on the feet. The direction people’s toes point can be very telling. If the toes are pointed toward you, that’s good. If they’re pointed away from you, that means your target would rather be elsewhere. If the toes are pointed in toward each other, see our next point.

Reassure people you’re harmless. To advertise your friendly intentions and that you have nothing to hide, presentan upturned palm mid-conversation or shrug your shoulders in an “aw-shucks” gesture. These tactics work well for both sexes, although they work especially well for women, since appearing small and helpless can inspire men to take care of them. To really lay it on thick, women can turn their toes inward toward each other to further shrink in size and emphasize that they need protecting.

Enter the zone. The area extending eighteen inches around someone’s body is someone’s “intimate space”—a no-go zone when you first meet someone. But as things get more intimate, find some excuse to step into this zone (to allow someone behind you to pass, for example) then step back out. If someone likes you, he or she will respond by taking a step closer to you.

Reach out and touch something. Early on, flirters will often fiddle with their hair, stroke their arm, or rub their knee. Take it as a good sign, fueled by a subconscious desire to be touched by someone else. When you first attempt to initiate physical contact with an acquaintance, try tapping a forearm, an elbow, or the back of a hand—all safe options to get things started without coming on too strong.

A touch on the back of the hand can also work wonders. In another experiment, librarians who touched book borrowers on the hand were rated more positively, and borrowers were also more likely to remember the librarian’s name. In another study, waitresses made significantly higher tips by touching the customer’s forearm when handing over the menu. Touch warms people up, which can come in handy if you’re hoping to one day transition to the grand finale: heading to bed together.