THE

RISING

With the Edict of Milan, Roman emperor Constantine liberated Christianity—and then it boomed in the empire’s capital and beyond. The centuries passed, and a headquarters formed in Rome near the Tiber River. A first St. Peter’s was built, then a successor in the 16th century. There was a principal architect, in the specific and also grandest sense of the word, of the Vatican, as well as many colleagues, including Donato Bramante, Carlo Maderno and Gian Lorenzo Bernini. He was Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, born in 1475 and destined not to die until 1564, and he is often mentioned with Galileo, Newton, Einstein and very few others as a personification of human imagination, talent, work ethic and achievement.

STEPHEN ALVAREZ/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

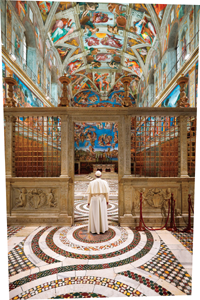

LOVE, PASSION AND HONOR are reflected in the ceiling of St. Peter’s Basilica, the famous dome fashioned and begun by Michelangelo and brought to completion after his death by Giacomo della Porta. A good bit of Michelangelo’s vision for the physical plant of the basilica would be realized collaboratively or posthumously, not least since he was already in his seventies when appointed capomaestro —master builder—of the enormous project in 1546. Michelangelo was not happy with the commission: “I undertake this only for the love of God and in honor of the Apostle.” He insisted, as a condition of his employment, that he be given free reign to proceed as he chose.

In the foreground of this photograph is Bernini’s ornate baldacchino—a nearly 100-foot-high ornamentation, largely of bronze, above the central altar. Bernini was supported, beginning in 1624, by Pope Urban VIII, and a central assignment was the embellishment of the basilica. Bernini would stick to this task for nine years.

As Michelangelo said, the toil and dedication of these artists is a testament to their desire to honor the subject: the Apostle.

THE APEX

JEFF J. MITCHELL/GETTY

THE DOME OF THE BASILICA is (above) on the night of March 10, 2013, two days before the opening of the conclave that will elect Pope Francis as successor to Benedict XVI; 115 cardinals are gathering in Vatican City to vote for the Catholic Church’s 266th pope. Below: A sketch outlining Michelangelo’s plans for the dome. The commission for the dome was assumed from Antonio da Sangallo the Younger by Michelangelo and reflects the latter’s genius top to bottom. The dome itself, with its double shell, has an inside diameter of half a football field, an interior height of a hundred yards and a height to the top of the cross of nearly 150 yards. It is lighted, brilliantly, by 16 windows. On the perimeter is the inscription, “You are Peter and upon this rock I will build my church and I’ll give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven.”

RMN-GRAND PALAIS/ART RESOURCE, NY

The dome would be the model and inspiration for a number of subsequent architectural achievements throughout the world, such as the Hôtel des Invalides in Paris, built between 1677 and 1706; St. Paul’s Cathedral in London, which was completed in 1710; and our own U.S. Capitol, which rose on a hilltop in Washington, D.C., beginning in 1793.

Michelangelo worked in Rome, but his legacy can be seen everywhere.

ALBERT MOLDVAY/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

HERE WE SEE a detail of Michelangelo’s sculpture the Pietà—the Virgin with her dead Son—which of course is housed at the basilica. It can be considered, in fact, St. Peter’s ultimate symbol among many. Michelangelo completed this in 1499 when he was only 24 years old. It was vandalized in 1972 but has since been restored.

THE MASTER’S ART

THE ART ARCHIVE/ASHMOLEAN MUSEUM/ART RESOURCE, NY

LUCAS SCHIFRES/GETTY

SCALA/ART RESOURCE, NY

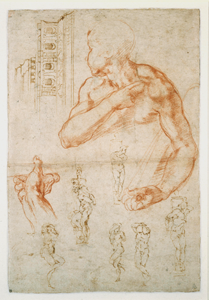

THREE DRAMATIC PICTURES, seen from top to bottom, are illustrative of the hand of Michelangelo: First, chalk studies for the ceiling of the Vatican’s Sistine Chapel and for the tomb of the pope who had summoned Michelangelo to Rome in 1505, Julius II; then the part of the Sistine’s ceiling depicting “The Creation of Adam”; and Lastly, also from the chapel, the so-called thinking skull from the “Last Judgment” fresco.

The Sistine’s ornamentation as well as the tomb were Pope Julius’s idea, but once Michelangelo was at work in the chapel, inspiration took firm hold, Julius’s original thoughts were scrapped piece by piece, and a relatively simple plan exploded into a sweeping history of the Bible with more than 300 figures painted on a surface area of more than 300 yards. Everything from “The Drunkenness of Noah” to “God Creating the Sun and the Moon” to “The Garden of Eden” would be part of this astonishing effort.

Michelangelo knew what he wanted to do; he always knew what he wanted to do. At one point, Pope Julius asked the artist to retouch some figures in gold so the depicted people wouldn’t look so poor. Michelangelo replied that these subjects most likely would have been poor when on earth, and that was the end of the discussion. Similarly, the original commission called for the 12 Apostles seen against a star-filled sky. Michelangelo instead saw something altogether more elaborate: a section on the “Fall of Man,” and then the prophets’ “Promise of Salvation” and also a “Genealogy of Christ.” This is what now adorns the Sistine Chapel ceiling, including “Deluge,” “Isaiah,” “Cumaean Sibyl” and much more. The nice starry-sky picture remains to be painted on another ceiling by someone else.

It’s interesting: Michelangelo’s own religious impulses were as a seeker and often a doubter. Not only wasn’t he rapturously devout, he wasn’t particularly sociable. In short, he wouldn’t have been seen as any kind of humane, charismatic figure. But when he lost himself in his work, he was somehow transformed. Perhaps more simply: His talent was unleashed.

CHURCH AMONG CHURCHES

YOU COULD ARGUE both ways in retrospect: It was impossible for the Vatican to happen, or the Vatican was bound to happen. With Emperor Constantine’s first initiatives in the 4th century, Rome was instantly the place for the Church, and even with Constantine’s eventual departure and the subsequent formation of Christianity’s Byzantine church, headquartered in the newly renamed Constantinople, Rome fiercely claimed to be the core. After general unrest in Italy had settled sufficiently, and after what was clearly not the whole of Christianity but “Roman Catholicism” grew in power and definition, it seems inevitable that the former precincts—descendant parishes of the so-called Seven Churches of Rome—would coalesce around a hub. As the Middle Ages yielded to the Renaissance, Pope Julius II’s heaven-sent genius, Michelangelo, as well as Michelangelo’s brilliant and dedicated associates and successors, ensured this would be a hub like no other—even a new Jerusalem.

JAMES L. STANFIELD/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

Today, in that hub, are some of the world’s greatest libraries and museums filled with treasures commissioned, treasures bought and treasures plundered down the centuries. There are grand palaces and grander cathedrals, as well as smaller, secretive chapels. There is, atop the hill, a Vatican radio station.

In order to properly honor this unique and phenomenal bequeathal, the modern Vatican is constantly undergoing renovation in one of its wings or another. This work applies to the art as well as the infrastructure, and at bottom a nun repairs a tapestry designed by Raphael while the somewhat controversial cleaning and restoration of the Sistine Chapel ceiling, which had been darkened by years of candle smoke and other residues, is filmed by a television crew. This work was done methodically in the 1980s and ’90s.

JAMES L. STANFIELD/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE

Below: Pope Francis makes a spontaneous visit to the Sistine Chapel after his Urbi et Orbi address on Christmas Day, 2014. This is the room that all Catholics and millions more hope to visit one day, and it can be reliably reported: The Sistine Chapel is perhaps smaller than you might expect but a thousandfold more grand than ordinary imagination can conceive.

DAVE YODER/L’OSSERVATORE ROMANO/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CREATIVE