The best place to hide a message is somewhere completely innocuous. In the course of history, messages have been concealed inside animals and people, pencils and even coins, and that humble material wax has been a friend to many a spy.

The principal motive for sending secret messages was for military or diplomatic confidentiality. Generals and senior officials wanted to know that even if their message carriers were intercepted, no one would understand what information they had with them.

The early Greek historian Herodotus, writing in about 440 BC, tells a trio of tales involving concealed messages. In the 6th century BC, Harpagus, a Median soldier, was plotting against Astyages, his own king. He wrote a message to the king’s enemy, Cyrus, promising to change sides, and hid it in the belly of a hare, which was carried by a messenger in the guise of an innocent hunter. Its delivery prompted a Persian revolt against the Medians, and Harpagus did indeed betray his king, who was replaced by Cyrus. The idea of hiding a message in an animal was still around in 16th-century Italy, when Giavanni Porta records the practice of feeding a message to a dog, which could then be taken on an apparently innocent trip where it would be killed to retrieve the information.

In another complicated plot, this time by the Greeks against the Persians, Histiaeus earned a place in the pantheon of secret messages. Wishing to prompt a rebellion against Darius, but stranded at court in his role as ambassador, Histiaeus somehow had to encourage his son-in-law Aristagoras to attack the city of Miletus. Clearly prepared to sacrifice speed for secrecy, Histiaeus shaved a slave’s head, branded his message onto the poor man’s scalp and only sent him on his way when the hair had grown over the writing. It worked: the city was taken by the Greeks and established as a democracy, prompting further rebellions against their Persian rulers.

In 480 BC the Persians completed a five-year military build-up and launched an attack on Athens, believing their plan to be a secret. However, a Greek called Demaratus had witnessed their preparations and managed to get a warning to his compatriots. Messages were usually sent on wax tablets, but these would obviously not be kept secret. So Demaratus instead carved his message into the wooden base of the tablet, which he then covered with wax. The blank tablets arrived without incident, but baffled their recipients until they scraped away the wax and discovered the warning. This allowed them to repel the attack, which was thought to be crucial in preserving their independence.

The Greeks were not alone in their need to communicate secretly, or in their use of wax. The ancient Chinese wrote messages onto silk, which was then scrunched into a little ball and coated with wax. The messenger would hide or swallow the ball to conceal it during his journey. Roman historian Tacitus tells of wounded soldiers concealing writing on their bandages, of sewing messages into the soles of sandals, and even writing messages on a thin sheet of lead and rolling it into an earring. More recently, Cold War Russian spies hid microfilm in hollowed-out pencils, batteries and coins.

COVERT WRITING

• The term for hidden writing is steganography, from ‘stega’, the Greek word for roof or cover, and ‘graphy’, meaning writing.

• The practice continues today: in electrical communications it is called transmission security.

What better way to conceal a message than by rendering it invisible? It saves all the effort of devising and using a code and allows open, apparently innocent communication between people who are being observed. The technical term for this is steganography.

Steganography can also be used for secret communication, embedding data on the screen rather like a microdot hidden in a piece of punctuation. Its advantage is that an interceptor is unlikely to detect the presence of the data, allowing secure communication, albeit of fairly short messages.

A number of natural materials have been used for invisible writing for thousands of years. Both the Greeks and Romans extracted such inks from nuts and plants. For example, in about AD 100 the Roman writer Pliny recorded that he could obtain a liquid from the tithymalus plant (which is part of the euphorbia family). When he wrote with it, the message vanished as the ink dried, but it reappeared when the paper was gently heated.

Pliny could have chosen one of many other organic liquids such as onion juice, vinegar and apple juice, and any citrus juice. All turn brown when gently heated (a hot iron, hairdryer or light bulb is best – actual fire is too hot). This knowledge has benefited secret agents across the centuries, some of whom resorted to their own urine when other supplies ran out. Cola drinks also work with this method (use the non-diet kind, as sugar is required).

A large number of chemicals also function as invisible ink (also known as ‘sympathetic ink’). They are activated by another chemical called the ‘reagent’. Examples include iron sulphate solution, which reacts to solutions of potassium cyanate, or sodium carbonate and copper sulphate, which react to ammonia fumes.

Some of these chemicals can be harmful, so do not try this yourself unless you are a chemist or a trained spy! However, one experiment you can do is to write in milk on thick paper, using a brush rather than a pen so you don’t leave any indentations on the paper. Watch as your words disappear, then rub dark powder such as ashes or charcoal across the page, and your message returns. In Nazi Germany, ballot forms were secretly numbered in milk to allow checking of how people voted in plebiscites.

Banks and amusement parks sometimes use invisible inks that shine under ultraviolet radiation known as ‘blacklight’. The inks contain colour-brightening chemicals similar to those found in laundry washing powders.

An intriguing by-product of the internet age is the re-emergence of secret writing as a valuable tool. If you’ve ever been baffled by how some seemingly unrelated websites appear when you are searching for something on the net, the answer echoes the methods described above. It is possible to hide text on the screen either by typing white text on a white background, concealing it on a non-printable area of the page, or in graphics or a music file. You can’t see it, but the search engines find it. This embedded text gets their website included in a wider range of search results. Some companies go a step further and hide their competitors’ names on their own websites, meaning that their site pops up on the screen whenever someone keys in the name of their rival.

Sending sheets of ‘blank’ paper is likely to arouse suspicion, so agents writing in invisible ink do so on paper with an innocuous message, or use shopping lists or pictures as a background.

HOT NEWS

Natural invisible inks are made from organic fluids, which are rich in carbon. The liquid evaporates but some soaks into the paper. When heated, the carbon chars and turns brown.

Speaking directly to someone else is, of course, the most efficient way of communicating, but when there is danger of other ears listening in, a spoken code is required. Most of them are quite simple to break once you know the key.

The simplest spoken code is Pig Latin, a letter rearrangement code that is particularly popular with children. There are three basic rules:

• Words that start with vowels have ‘ay’ added to the end, so ‘actually’ becomes ‘actuallyay’.

• For words starting with a consonant, that letter is moved to the back, and then ‘ay’ is added at the end, so ‘can’ becomes ‘ancay’.

• If two consonants are at the start, they are moved to the end, adding ‘ay’, so ‘speak’ becomes ‘eakspay’.

Thus, ‘Actually a child can speak Pig Latin well’ is spoken as, ‘Actuallyay aay ildchay ancay eakspay igpay Atinlay ellway’. With practice, Pig Latin can be spoken and understood at quite a pace. In a variation known as Tut Latin, the sound ‘tut’ is added between each syllable.

Another spoken code language is Opish, in which ‘op’ is added after each consonant. Thus ‘book’ transforms into ‘bopookop’ and ‘code’ is ‘copodop’. Words become very long and it becomes very hard to decipher meaning. Similar to Opish is Turkey Irish, in which ‘ab’ is added before every vowel sound, so ‘book’ becomes ‘babook’ and ‘code’ is now ‘cabode’. As with Pig Latin, this is a novelty language rather than a code that can be used for meaningful communication.

A more sophisticated spoken code disguises information. For example, just prior to the German occupation of Norway in 1940, telephone and radio calls from Nazi agents were intercepted. They appeared to be sending sales and tonnage information about fishing, but analysis showed that they were actually communicating details of ships, using the numbers with which vessels are identified in the shipping bible Lloyd’s Register.

Later in World War II, innocent-sounding calls discussing the flower market were also found to be disguising information about which ships were in harbour and the nature of repairs being undertaken.

Cockney rhyming slang is a spoken code that has survived for about 200 years. It substitutes (usually) two words for one, with which it rhymes. So ‘butcher’s’ in the heading above is short for ‘butcher’s hook’, meaning ‘look’. Traditional examples are:

• Apples and pears = stairs

• Barnet (fair) = hair

• Brown bread = dead

• Canoes = shoes

• Dickie Dirt = shirt

• Mahatma (Ghandi) = brandy

The slang continues to develop. Here are some more recent introductions:

• Basil (Fawlty) = balti

• Billie (Piper) = sniper or windscreen wiper

• Metal Mickey = sickie

There are various theories about how Cockney rhyming slang started. It was certainly in London’s East End, and definitely devised to prevent other listeners from knowing what was being said. It may have originated from:

• Villainous builders in the London docks.

• Market vendors talking about customers.

• Prisoners who didn’t want their guards to understand what they were saying.

• Thieves aware that Robert Peel’s newly launched police force might be around.

All of the spoken codes described so far can be broken relatively easily. One spoken code that defied analysis, however, was used by the US forces in the two world wars: a language that none of the opposing forces could understand.

In 1918, orders within D Company, 141st Infantry were openly transmitted by field telephone in complete security because they were spoken by one of eight serving Choctaws, a native American group from Oklahoma.

Other native tongues were also used. The unique advantage was that these languages had developed, geographically and linguistically, far away from other peoples and conveyed meanings with precise pronunciation and hesitations, which were unintelligible to outsiders.

The practice was repeated in World War II, when as many as 420 Navajo speakers were used by the Marines in the Pacific combat zone, baffling Japanese intelligence personnel. The story was told in the 2002 film Windtalkers, starring Nicolas Cage.

Hiding words within words has proved to be a popular method of secret communication as it is very hard to detect, the carrier text being an everyday innocuous message.

In 17th- and 18th-century Britain, it was very expensive to send letters by post, but sending newspapers was cheaper and even, at times, free. Thrifty communicators seized on this and adopted the puncture code that had been described by Greek historian Aeneas the Tactician 2,000 years before.

They would make small pinpricks, or mark tiny dots, over certain letters so that they could spell out a message, which could then be cheaply dispatched to their correspondent. The practice continued until postage prices were altered in the middle of the 19th century. However, German spies used this exact system during World War I, and again in World War II, using invisible ink.

The disadvantage of this method is that a lot of the carrier text is redundant: so many words are delivered from which only fairly short messages can be communicated. The next logical step is to write your own ‘carrier’ message, which can be decoded with an agreed formula.

A simple example of this is an acrostic: a sentence in which the initial letters of words spell out a message. These are called null ciphers and are often employed in puzzles and crosswords. For example, cuddly attack tiger spells CAT. They are also used as memory aides, for example BRASS is an acronym for how to fire a rifle: Breathe, Relax, Aim, Sight, Squeeze, and the sentence Every Good Boy Deserves Favour sets out the letters on the lines of sheet music when written in the treble clef.

This method is thought to be the inspiration for the Christian sign of the fish. In the early days of Christianity, when it was necessary at times to keep your faith secret, ancient Greek was widely spoken. The phrase ‘Jesus Christ Son of God, Saviour’ rendered in ancient Greek is ‘Iesous Christos Theou Uios Soter’. The first letters spell ICHTHUS, the Greek word for ‘fish’. So followers of Jesus could use a fish sign, or the word ICHTHUS, to show that they were Christian.

In general, devising an innocent-sounding acrostic message that makes sense is very tricky. However, choosing to send a message via, say, every third letter is far easier to devise, and harder to spot. A famous example of this is the English Civil War story of Sir John Trevanion, a royalist locked in Colchester Castle awaiting probable execution by his Cromwellian captors. He received a letter that began: ‘Worthie Sir John: Hope, that is ye beste comfort of ye afflicated, cannot much, I fear me, help you now. . .’.

On the surface it was just a rather verbose letter, and the guards charged with checking his letters could find nothing suspicious. But take out every third letter after a punctuation mark and the entire letter creates the more useful message: PANEL AT EAST END OF CHAPEL SLIDES. Sir John promptly asked to be allowed to pray at the chapel, and made his escape. Some historians question details of this tale, but it does illustrate the value of an acrostic code.

A similar strategy was used by a German spy in World War II, whose message ‘Apparently neutral’s protest is thoroughly discounted and ignored. Isman hard hit. Blockade issue affects pretext for embargo on by-products, ejecting suets and vegetable oils’, spells out ‘Pershing sails from NY June 1’ if you read only the second letter of each word.

A similar simple encoding method is to conceal the true message with extra words, and include guidance on how to identify which words to read. For example, the 1/4 at the start of this message instructs the reader to ignore the first and every fourth word: ‘Tom: 1/4 gifts do not arrive often father will be pleased here, Lucy’ so the plaintext reads ‘Tom do not arrive father will be here, Lucy.’

Another method of sending a message concealed on a page of writing is the stencil method, in which the hidden text is read through ‘windows’ cut into card or fabric laid over the letter.

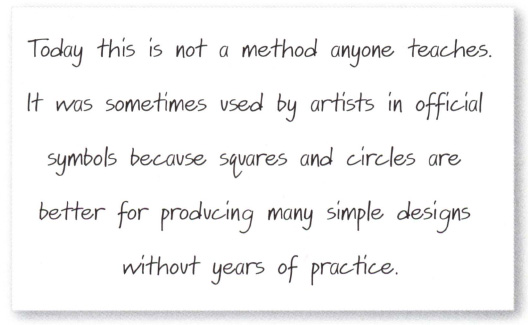

This code was invented by an Italian doctor and mathematician called Girolamo Cardano in 1550 and is known as the Cardano grille. Small holes were punched in an irregular pattern in a piece of card, which was used as an overlay on top of a piece of writing. This method allows for reading only single letters at a time, but it can be adapted to use larger holes so that syllables or whole words appear in the window, although this then makes it more difficult to disguise the message.

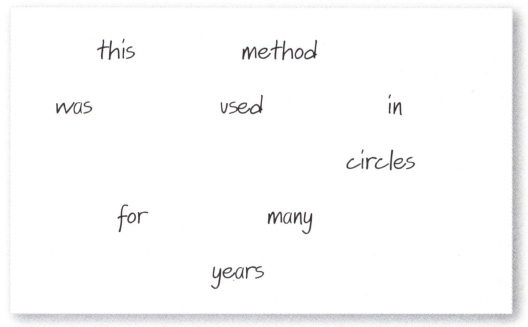

The three stages of creating a Cardano grille

Provided the same card with cut-outs is not used more than a few times, the method is safe, and it was certainly widely used in diplomatic correspondence for hundreds of years after its invention. The system also requires there to be two identical copies of the stencil, or that it be sent to the receiver in some guise. But over-use of the card would allow a code breaker to identify where the ‘windows’ are, allowing instant reading of the real message. There is also a risk that the message created to ‘camouflage’ the hidden words may be so clumsily worded as to create suspicion.

THE ROTATING GRILLE

A refinement of the method is the ‘turning grille’ system, in which the grille is rotated through 180 degrees or flipped every, say, nine letters. This is remarkably effective, provided the windows never overlap.