IN 1519, the year Magellan sailed from Spain on his tragic world-altering voyage, another adventurer sailed from Cuba to the Yucatán Peninsula, to further explore the Spanish half of the world. Hernán Cortés, whose name would become a byword for the ruthless and violent conquistadors of legend, would lay the foundation for Spain’s overseas empire within a few years.

Cortés was a minor Castilian noble who, after two years at the University of Salamanca studying law, joined an expedition to colonize Hispaniola. He arrived in the port of Santo Domingo in 1504 when he was eighteen years old. Like most colonists in the newly discovered islands, he was a footloose youth, eager for adventure and opportunity, for a chance to see a world that was literally becoming larger during his lifetime. On Hispaniola, he was given land for a farm and, in the spirit of the times, a contingent of native workers to toil for him. The several thousand Spanish colonists on Hispaniola, who by this time had been there for a decade, were engaged in placer gold mining and plantation-style farming using indentured or enslaved native workers. The entire population of the island had been brought under Spanish control, and within decades many of the other Caribbean islands were depopulated to meet the labour needs of the increasing numbers of settlers.

The first Spanish colonists lived in rudimentary straw or mud huts, suffered from shortages of food and medicine and endured the ravages of unknown diseases. The enslaved Taíno natives fared much worse; by 1503, Spanish merchants were importing black slaves from the Portuguese trading posts along the West African coast to replace the Taíno slain by Spanish brutality and disease. By 1530 the islands of the Greater Antilles (Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico) were virtually devoid of their indigenous inhabitants.

The Spanish colonists brought familiar European crops with them, but found that olives, grapes and wheat were unsuited to the tropical climate of the Caribbean. Rice, oranges, lemons and figs, however, flourished and were growing wild within a few years. The consistently hot and humid climate was found to be extremely beneficial to sugar cane, and the first sugar mill began operating as early as 1508. By the 1520s, the sugar plantations on Caribbean islands were flourishing, beginning the long tradition of sugar farming and the production of rum from the sugar cane. Bananas, also brought to the islands by Spanish colonists, adapted well to their new climate; indeed, quite a few of the crops for which the West Indies are well known today originated in southern Spain.

Many of the colonists, however, were not satisfied with their flourishing plantations, made profitable by slave labour. Continuing their ravenous quest for gold, they moved from Hispaniola to Cuba, which was equally suited to agriculture, but had greater quantities of gold in its streams and creek beds. They had perhaps been inspired by Cortés’s famous claim that “I came here to get rich, not to till the soil like a peasant.” Certainly they were in agreement with it.

Cortés was among the warriors who left Hispaniola in 1511 with Diego Velázquez on an expedition to conquer the island of Cuba. After the conquest of the “simple and gentle” people who lived there, Cortés impressed Velázquez, the new governor, with his abilities and legal training. Now in his mid-twenties, Cortés owned a large estate with numerous slaves and a placer gold mine; he had a position of respect and authority among the colonial establishment. But he remained unsatisfied; his ambition and thirst for adventure were unquenched. After several years on the island he grew quarrelsome and got into trouble with his former friend Velázquez, notably over his amorous liaisons with the governor’s sister-in-law.

Spanish ships continued to explore the lands west of the Greater Antilles, occasionally capturing unsuspecting natives. One expedition searching the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula in 1518 encountered a contingent of peaceful people near Tuxpan who presented the Europeans with gifts of gold—to them, a soft, easily worked metal, but to the Spaniards a source of wealth and power. The ships returned to Cuba with plenty of gold jewellery, skillfully worked in intricate patterns, and Velázquez was “well contented” with the quantity of loot. Within months he had organized a second expedition to Mexico. In February 1519, he appointed the energetic Cortés as captain. Cortés’s band consisted of about five hundred soldiers and thirteen horses, transported in eleven lightly armed ships.

What transpired in the following two years has become the foundation of legend, alternatively a triumph or a disaster unparalleled in the annals of history—one that led to near-genocide, cultural annihilation and the unrestrained plundering of the riches of one continent to fuel the dynasties and internecine quarrels of another.

In March 1519, Cortés arrived on the east coast of Mexico and founded the town of Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz, south of Tuxpan.

The settlement became Spain’s porthole into the untapped wealth of the Aztec Empire—a civilization arguably more advanced than that of Europe and rivalling the splendour of ancient Egypt. It was a nation state of about 25 million people (compared with Spain’s eight million) in central Mexico, organized into an efficient hierarchy of subjugated states. It was well acquainted with the art of war. However, after centuries of constant conflict with the Moors, the Spanish conquistadors had perfected the art of war. They had excellent ships for transportation, strong Toledo steel for weapons, armour and guns, and a structured military culture. Impoverished, disease-ridden slum-dwellers in Spain were seemingly willing to risk anything to better their lives.

Beginning with this meager force and with the use of astute tactics, Cortés penetrated to the heart of the greatest empire in the Americas, the lake-encircled capital of Tenochtitlán in the central valley of Mexico, from which Aztec power radiated to the surrounding regions. Using a combination of diplomacy, intimidation and deceit, Cortés plundered the city and grabbed the emperor, Montezuma, as hostage. Montezuma first tried a policy of appeasement, hoping to pay the Spaniards to leave. Wealth beyond their dreams was presented to them, including, according to one soldier, “a helmet full of fine grains of gold, just as they are got out of the mines.” But far from appeasing the conquerors, the treasure stimulated their avarice. The conquistador continued: “This gold in the helmet was worth more to us than if it had contained [a small fortune], because it showed us there were good mines there.”

“Many factors contributed to this amazing triumph,” O.H.K. Spate writes in The Spanish Lake. “Armour, horses, crossbows, firearms, disciplined tactics and valour, all important, would not by themselves have sufficed the numerical odds.” The relatively recent and oppressive expansion of the Aztec Empire and its hated overlordship had produced many resentful clans, tribes and cities, rebellious tributary states. They were more than eager to aid— directly and indirectly—any challenge to this brutal regime, which sent captured warriors and slaves, bound in chains, to have their still-beating hearts cut out in the temples atop the great pyramids. The story of how Cortés accomplished his military and diplomatic feat is rich and detailed, and subject to various interpretations, much as the debate over Cortés as an individual oscillates between declaring him a hero and denouncing him as a vicious villain. But disease had a far more devastating effect on the Aztec people than did Cortés’s military force.

The people of the Americas had little resistance to European diseases. They died in such numbers from smallpox, flu, measles, bubonic plague, yellow fever, cholera and malaria that survivors could not remove the decaying corpses from the moats and alleys. There were simply too many dead bodies to move. In Tenochtitlán, carrion was everywhere. The cloying stench of funeral pyres mingled with the sweet rot of decomposing flesh. The great marketplace was clogged with cadavers piled like hay bales beside the once free-flowing avenues. One Spanish commentator noted sadly that “the Indians die so easily that the bare look and smell of a Spaniard causes them to give up the ghost.” According to Noble David Cook in Born to Die, disease killed as much as 90 per cent of the population in some regions and was “the greatest human catastrophe in history, far exceeding even the disaster of the Black Death of medieval Europe.”

The floodgates to the wealth of the Americas were now flung wide open. Roving bands of privately funded adventurers scoured the Americas from Florida to Peru, searching for another source of easy treasure. The Mayan city-states in the Yucatán Peninsula and Guatemala were subjugated by Pedro de Alvarado in 1523, and Francisco Pizarro led his band of privateers south to Peru in 1531. By 1533, Pizarro had defeated the Inca Empire and conquered the city of Cuzco by treacherously capturing Emperor Atahualpa. In Florida, Hernando de Soto led an expedition in search of the Fountain of Youth and the Seven Cities of Cibola in 1539. In all these endeavours, the native peoples of the Americas—enslaved, starved, displaced and ravaged by disease—suffered horribly. Many were killed outright, others were compelled to labour, chained in work gangs or bent under the lash in silver mines in Peru and Mexico.

To still their consciences and justify their actions, conquistadors read aloud the Requerimiento—a document first devised during Ferdinand’s reign to justify the conquest on religious grounds. But even Spanish clerics, accustomed to religious intolerance and conditioned for cruelty by a seven-century conflict with the Moors, could not condone the brutal crimes of the conquistadors and colonial administrators towards the indigenous peoples. The writings of Friar Diego de Landa and Bartolomé de Las Casas, published widely throughout Europe in the late sixteenth century, exposed the cruelty of the conquerors and contributed to the “Black Legend” of Spanish atrocities in the New World. Modern scholars estimate that the carnage caused by conquest, enslavement and disease throughout the Americas amounted to tens of millions of deaths.

Cortés laid the foundation for the Spanish Empire. In the coming decades the speed and totality of the Spanish conquest would completely transform world history as Spain, unopposed by Portugal or any other European maritime power, consolidated its empire and exploited the resources of all of Central and South America, shipping vast cargoes of gold and silver bullion across the Atlantic and transforming Spain not only into the richest nation in the world but into an empire having the largest territory of any since Genghis Khan’s.

A few years into this conquest, however, an unexpected visitor arrived in Tenochtitlán, which had since been renamed Mexico City by its conquerors. The visitor, Father Juan de Aréizaga, surprisingly, came from the west, from the direction of the Pacific Ocean. He had an unusual request for Cortés.

IN THE 1520s, years before the Mexican and Peruvian conquests were completed, the world’s wealth was believed to lie in the Spice Islands. The monarchs of Spain and Portugal, Charles I and João III, were in the midst of a quarrel over whether or not Magellan had violated the Treaty of Tordesillas during his circumnavigation. Charles was in the process of planning a follow-up voyage to retrace Magellan’s route around South America and across the Pacific Ocean. Rather than go to war attacking each others’ ships in the Moluccas, and perhaps risk damaging the foundation of the treaty that gave each of their nations half of the non-Christian world, the two monarchs agreed to hold a conference at which the greatest cosmologists, navigators, cartographers and other scientific, legal and ecclesiastical luminaries from both countries would meet to discuss the division of the world—a most vexing political and diplomatic dilemma.

The experts convened in April and May of 1524 on a bridge over the Guadiana River, the border between their two kingdoms. They were determined to hash out an acceptable compromise on the location of the treaty’s line of demarcation on the far side of the world, or perhaps just to play for time while each nation sent out rival expeditions to the Spiceries. The meeting was called the Badajoz Conference because the bridge, however symbolically neutral, proved to be a poor location for hosting an international diplomatic conference and the delegates retired alternately to the border towns of Elvas and Badajoz. Many notables were present, including the cartographer Diego Ribera (who later produced a chart that displayed the conflicting claims of Portugal and Spain, giving a clear no man’s land as a buffer between them), Sebastian Cabot, Juan Sebastián de Elcano, the captain who brought the Victoria home after Magellan died, and Giovanni Vespucci, brother of the famous navigator Amerigo.

The proceedings were nearly derailed before any meetings took place. As the august cluster of Portuguese negotiators strode across the bridge to meet their Spanish counterparts, a small boy who was drying laundry in the sun with his mother piped up with a question for them: were they truly going to divide the world? The distinguished Diogo Lopes de Sequeira, until recently the governor of the Portuguese enterprise in India, solemnly responded in the affirmative. With a smirk, the boy shifted his clothing and stuck his posterior towards them, announcing that they should “Draw your line right through this!”

Once the brouhaha died down and the Portuguese delegates had been persuaded to drop their demands to have the boy whipped, the conference began. It dragged on for nearly two months. All the luminaries dutifully attended the meetings and presented their cases, arguing their positions. Not surprisingly, the expert opinion was divided along national lines. The two sides couldn’t even agree on the standard length of a degree of longitude in leagues (the original longitudinal location of the line of demarcation in the Treaty of Tordesillas was expressed as 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands), so much of the conference was actually little more than a delaying tactic. Not only could the experts not come to a consensus on the length of a degree, but the true size of the Pacific Ocean remained unknown. Distance at the time was recorded by dead reckoning, which produced vague and sometimes contradictory estimates.

The Spanish delegates pushed for a quick compromise decision, based on their estimates of the location of the line of demarcation, which although it varied, always put half or all of the Moluccas in the Spanish part of the world. The Portuguese, who favoured a longer time frame to reach a decision—during which time each nation would be restricted in its activities until the determination was made—wanted to rely on yet-to-be-perfected astronomical calculations. Though no one could have known it at the time, the Portuguese had the more accurate claims. Their arguments placed nearly the entire region of the Moluccas in the Portuguese half of the world, leaving only a handful of tiny islands—the Marianas, the Palaus and Micronesia—for Spain. Hardly worth a trip across the Pacific, they must have felt.

Not only did the delegates lack any reliable method of calculating longitude, but they also had to contend with dozens of distorted and grossly inaccurate maps and globes. Some of these maps were designed originally to argue different political points, such as to deter voyages to the Indies via the Portuguese route by exaggerating the distance—something that played nicely into Spanish hands by making that half of the world seem larger. Even if the two nations had been sincere in their attempts to create a cosmological web of longitude that was disinterested in terms of the nations’ political and mercantile interests, the technology and knowledge to do so simply did not exist at the time. Accuracy in determining longitude outside Europe progressed slowly and incrementally throughout the sixteenth century, primarily as the result of Jesuit missionaries following a handful of documented eclipses in places like Mexico City, Calicut in India, and China.

After months of wrangling at the Badajoz Conference, each side refused to concede anything to the other and both claimed virtually all of Indonesia. It is hard not to find this an amusing exercise: delegates from two small European nations who had recently discovered a method of sailing great distances to reach these new-to-them parts of the world, solemnly presenting to their colleagues and counterparts, with a straight face, arguments that were based on faulty and grossly inaccurate information (and certainly knowing full well the dubious provenance of their facts), haggling over the sovereignty of millions of people who had no idea such a conference was taking place, and who would have laughed and gone about their business had they known.

Nevertheless, the failure of the Badajoz Conference to produce anything mutually agreeable meant that the Spanish and Portuguese monarchs relied on the next-best method of gaining what they desired: the occupation of the Spice Islands, by force if necessary. Charles I had been planning a follow-up expedition to Magellan’s voyage even while the delegates at Badajoz were making their grand and airy arguments. He appointed Garcia Jofre de Loaisa, a well-connected soldier, to head this expedition, with Elcano as second in command. Calling his little fleet the Second Armada de Molucca, Charles commanded it to construct a permanent Spanish trading post in the Spiceries and to break the Portuguese monopoly—in defiance of the spirit, if not the rule, of the Badajoz Conference. He had little understanding of the great risks that such a voyage around the world entailed, nor did he appreciate how entrenched the Portuguese already were in the region.

The Second Armada de Molucca departed Seville to retrace Magellan’s route, but ill luck plagued the fleet from the start. Several of its ships were pounded by violent storms, separated from the fleet and destroyed before even entering the Strait of Magellan. One of the ships cruised north up the Pacific coast of Mexico but, lacking provisions, did not attempt a crossing. Instead, the captain sent Father Juan de Aréizaga ashore to purchase supplies from the local people. Eventually the priest made a trip overland to Mexico City (Tenochtitlán) and met with Cortés, then only a few years into his task of consolidating the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Cortés agreed to construct several ships and to send them from Mexico to the aid of the Second Armada.

Of the five ships to sail from Seville, and the two that actually set off across the Pacific Ocean, only one, the Santa Maria de la Victoria, arrived in the Spice Islands. Dozens of the crew members, including the captain, García Jofre de Loaísa perished miserably from scurvy in the vast expanse of the Pacific. The chronicler Andrés de Urdaneta recorded that “the people were so worn out from much work at the pumps, the violence of the sea, the insufficiency of food and illness, that some died every day.” The second in command, the indomitable Elcano, who must have felt he was reliving the worst moments of his first circumnavigation, was himself debilitated by the dreadful disease. In fact, only days after he assumed command of the single surviving ship from the once-proud Second Armada de Moluccas, he scrawled out his official will before dying on August 4, 1526.

When the ship and its meagre surviving crew reached the island of Tidore, they were met with a muted reception. The Portuguese had recently attacked the island in retaliation for the locals giving aid to Elcano years earlier. Soon word arrived from the nearby island of Ternate, where the Portuguese had established a fortified outpost, that the Santa Maria de la Victoria must immediately depart from the Portuguese half of the world. Eventually a small Portuguese fleet assembled and sallied forth to attack the Spanish ship. The ships blasted away at each other for days, until the Portuguese fleet sailed away in apparent defeat. For the Spanish, it was a Pyrrhic victory: the Santa Maria de la Victoria was so damaged that when the Portuguese ships returned they were able to capture the ship, strip it of value and burn it. The Spanish sailors fled to the interior of the island.

Thus began the unofficial war between Spain and Portugal in the Spice Islands, in which each side believed, or at least argued, that the line of demarcation gave it the exclusive right to trade and travel, and therefore the right to attack and kill trespassers. Each nation secured local allies for its cause: the Portuguese aligned with the sultanate of Ternate and the Spanish with the rulers of nearby Tidore and Halmahera, and they continued at war with each other for more than a year. The relief expedition sent out by Cortés also proved a disaster. Although one of the three ships he sent out did finally cross the Pacific and reach the Spice Islands, it was quickly captured by the Portuguese. Its crew was imprisoned and its cargo commandeered.

Undaunted, Charles I sent out a Third Armada de Molucca. This expedition was captained by the schemer Sebastian Cabot, then the pilot major of Seville and son of the inscrutable John Cabot. However, Sebastian soon returned, admitting failure after cruising the coast of Brazil as far south as the Rio de la Plata. Thereafter the cost to the Spanish crown was enormous, as fleet after expensive fleet met with disaster and destruction. Charles I refused to admit defeat, so high were the stakes both in commercial interests and in terms of personal pride: he did not want to allow the new Portuguese king, João III, any sense of victory or superiority. However, Charles I’s plans for yet another expedition, consisting of eight armed ships to attack the Portuguese and drive them from the Moluccas, never sailed. His moneylenders, the House of Fugger, refused to forward Charles the funds, and he was too indebted to raise the money from royal revenue.

Charles I’s management of Spain and the sovereign affairs of his other dominions had depleted the coffers of his realms. Particularly costly were his ongoing battles with Francis I of France and the cost of his failed armadas. During the better part of a decade Charles I had commissioned fifteen ships to sail to the Moluccas, and during that time only one ship—the Victoria, captained by Elcano after Magellan’s death—had ever returned to Spain. No ship had yet crossed the Pacific Ocean from west to east. Since no one had discovered a method of recrossing the Pacific, no spices would be able to reach Spain by sailing exclusively in the Spanish half of the world. It wasn’t until 1565 that the Pacific route, from Manila to Acapulco, was pioneered by Andrés de Urdaneta.

From Charles I’s perspective, the conquered lands of Mexico and later Peru were starting to appear more and more valuable. In fact they were yielding a far greater dividend, if one turned a blind eye to the bloodshed and suffering, than any of his expensive failures to reach the Spice Islands. Any victory for him there, on the far side of the world, would be so costly as to consume any profits. Coming to terms with the reality that he had limited finances must have been a blow to the emperor, who had been raised to believe that he was all-powerful. He was forced to ask himself the question: why bother with the Spiceries when the wealth from his own undisputed lands in the Americas was proving to be even more valuable?

In the mid-1520s, Charles I was also preparing for his upcoming marriage, a marriage that, in the long-standing Iberian tradition, was to be with João III’s sister Isabel, further linking the dynastic houses of the squabbling nations. It would not seem proper for the Spanish king to be marrying the Portuguese king’s young sister while sending Spanish fleets to battle the Portuguese in the Spice Islands; and although he had been doing exactly this for a few years, he evidently felt it was time to ratchet down the conflict and focus on his European problems. Perhaps diplomacy would achieve a victory where militancy could not. After his marriage Charles extended an offer to his new brother-in-law João to convene another conference, arbitrated by a representative of the papacy, where they could once again present their cases about which nation was entitled to sovereignty over the Spiceries.

The two sovereigns settled their claims to the Spice Islands in the Treaty of Zaragoza of April 1529. They agreed that the line of demarcation would fall to the east of the Spice Islands, in effect giving them all to Portugal, and that no Castilian subject would trade, travel or explore there. Charles I inserted a clause that if an accurate calculation of longitude were ever to be devised and if the calculation were to show that the Spice Islands lay east of the true line of demarcation, then the treaty would be void and Spain “will have the right and the action as that is now.” In return, João III, flush with cash from years of profits in the spice trade and without Charles I’s expensive involvement in European politics, agreed to forward to Charles 350,000 gold ducats, which were promptly used to fund his ongoing struggles against France.

The treaty curiously made no mention of the islands later to be called the Philippines, but the fact that they were situated securely west of the new line made them technically now part of the Portuguese half of the world. Many years later, in the 1540s, Charles I made another attempt to reach the Philippines, but it was not until 1565, after Charles was succeeded by his son Philip II (after whom the island group was named), that the first trading post was constructed at Cebu, and later moved to Manila.

The Treaty of Zaragoza effectively divided the world into two hemispheres, dominated by two maritime powers, although the Portuguese “half” was now slightly larger than the Spanish “half.” The historic agreement ended the first epic battle over control of the most valuable commodities in the world, and further refined the legal and geographical boundaries established in 1493 by Pope Alexander VI. These two favoured European nations grew rich and entrenched their monopolies in an era before they had any challengers. Although the treaty lessened the maritime rivalry between Spain and Portugal—rendering the positions of the Spanish and Portuguese exactly as they had been before Magellan approached Charles I with his daring, revenge-inspired scheme—it resulted in heightened tensions with England, the Dutch Republic and France.

GOLD: THE most valuable commodity in Europe, a symbol of permanence in an ever-changing world, the only universally accepted token of exchange, in use as such for almost two thousand years. Silver tarnishes, iron rusts and copper corrodes, but gold retains its lustre forever. In sixteenth-century Europe, gold was power: power to create armies and navies; power to construct churches; power to stimulate commerce and exploration; power to run a state. “Gold,” Columbus claimed, “is a wonderful thing! Whoever owns it is lord of all he wants. With gold it is even possible to open for souls the way to paradise!” For the adventurous, the New World was an exciting gamble; for the Catholic clerics it offered new heathens to convert and an opportunity for an expansion of the church hierarchy; for merchants it offered new trading monopolies with the rich “Oriental” lands; and for ambitious monarchs it was a new source of golden bullion to replenish the royal coffers—it was a new source of power. Unfortunately, gold is rare. The most easily obtained gold in Europe had already been mined by the Romans from the mountains of Spain and France until about AD 500, when the mines were depleted. And the world’s greatest sources of gold were not in Europe. In the sixteenth century, they were located in Mexico and South America, in the regions famously overrun by Spanish conquistadors.

The quantity of gold leaving the Americas for Spain increased steadily throughout the sixteenth century, from 52,700 pesos’ worth in 1522 (the value of Cortés’s first shipment) to over 800,000 pesos’ worth in 1570. By 1600, the Spanish crown’s intake of American treasure, which by this time included silver—extremely valuable for trade with China—amounted to a staggering sum. In 1628, a friar named Antonio Vázquez de Espinosa calculated the wealth that had left the Indies to be 1.8 billion pesos. By the early seventeenth century Spain had shipped from the Americas over three times the total amount of gold that had existed in Europe prior to Columbus’s voyage in 1492. And gold, silver, gems and pearls were not the only commodities extracted from the Americas. From as early as the 1550s, merchant ships in the annual Spanish treasure fleets carted commodities such as cochineal, tobacco, indigo, hides, ginger, brazilwood, lignum vitae, vanilla beans, sarsaparilla and many valuable and rare drugs.

All this wealth was controlled directly by the Spanish crown. In 1503 Ferdinand and Isabella had created the Casa de Contratación in Seville to rigorously regulate all commerce with the new territories, just as had been done earlier with the Mediterranean trade. The Casa illustrates perfectly the Spanish approach to the Indies trade—it would be controlled, at all costs, by the monarchy. No breach of protocol would be tolerated, and no alternatives would be accepted. The Casa evolved into a branch of the government devoted solely to preserving governmental control of the private trade between Spain and the Indies. Only Spanish ships and merchants could cross the Atlantic, and then only with the proper licence and papers, after having paid the proper taxes. This monopoly ensured that Seville was the only destination for all colonial treasure. Thus, from an early date the Spanish monarchs seized control of the Indies trade, nipping in the bud unregulated (and hence untaxed) trade and travel across the Atlantic.

As the stream of American bullion increased throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, so did the regulations, taxes and number of bureaucrats involved in the Casa. The Spanish-American trade during this time was likely the most regulated monopoly in the history of western Europe. However, unlike modern banking systems, with advanced electronic money transfers and letters of credit, the plundered wealth of the Americas was useless to the Spanish monarchy until the actual bullion arrived in Seville. And as the sixteenth century progressed, Spain needed this bullion—not for public works or social advancement programs, but to fend off creditors. Spain was in a state of constant and chronic debt to European bankers such as the House of Fugger, in order to fund immensely costly wars in northern Europe and to feed the ever-expanding central bureaucracy. Without any industry or trade network, the most significant tax base the Spanish crown had was the grossly inefficient Indies trade, which employed more regulators and officials than merchants or mariners. By the end of the sixteenth century, American bullion and commodities, plundered and transported across the Atlantic, directly contributed to more than 20 per cent to Spain’s state revenue.

As early as 1520 Spanish treasure ships returning from the Indies were threatened by French corsairs cruising the eastern Atlantic. (France and Spain were involved in almost chronic warfare throughout the sixteenth century.) In 1521 French privateers (private ships licensed by the French government to seize Spanish ships as they entered the coastal regions of Europe) captured two treasure ships from the Spanish fleet. King Francis I of France was astonished at the bulk of Mexican silver bullion, pearls and sugar: “The [Spanish] Emperor” he exclaimed, “can carry on the war against me by means of the riches he draws from the West Indies alone!” Referring to the line of demarcation, the French king also made the amusing, and perhaps apocryphal, statement, “The sun shines on me just the same as on the other; and I should like to see the clause in Adam’s will that cuts me out of my share in the New World.” Soon, the seas were crowded with privateers waiting to prey upon the lumbering, sluggish Spanish galleons, which were inefficiently constructed, captained, organized and defended. In order to defend against this new threat to national security, the Spanish monarchy quickly passed laws requiring all Indies ships to sail in convoy for security, and purchased a squadron of heavily armed galleons to sail with the convoy. In order to pay the new navy, the Casa levied another tax on the merchants, called the Averia. By 1543, Spain’s treasure fleet was defended by six heavily armed warships.

Although single heavily armed ships, called Ships of Register, sometimes sailed the West Indies route alone, and exceptions to all rules were routine, by 1566 two treasure fleets were sent from Seville to the Indies each year. The Mexican fleet, the Flota, departed in April or May (or later, as often there were unexpected delays and bureaucratic complications) and landed in Vera Cruz in New Spain, with ships branching off to Honduras, Cuba and Hispaniola en route. The Panama fleet, the Galleones, departed in August and sailed to Portobello in Panama and then to other cities along the Spanish Main in South America. For the return trip to Europe, the two treasure fleets congregated at Havana, Cuba, where they resupplied and reorganized. (Havana was an almost impregnable stronghold, not defeated until 1762, when it was plundered by the Royal Navy near the end of the Seven Years War.) Getting the gold and silver bullion from the Americas to Europe proved to be expensive and dangerous, and was always subject to the whims of nature and the unpredictable depredations of privateers and pirates.

Eventually the Spanish bureaucracy began to strictly regulate the number and type of ships, as well the amount of cargo each could carry, and the number of guns, the number of officials and the number of bureaucrats required for each Atlantic crossing. (An astounding number of officials were required by law to sail on Spanish ships, including the veedor, whose only responsibility was to make sure that the other officials were on board, the official rules obeyed and the official forms completed.) All these official positions were purchased from the government and had nothing to do with training, skill or knowledge. Needless to say, the Indies trade was not good for the long-term economy of Spain; ultimately, the nation became utterly dependent upon the annual shipments of American gold. While other European nations depended upon a healthy trade, and corresponding taxation, to generate state wealth, Spain depended on the bullion mined in the New Spain. No industry could generate profits greater than the profit from slave labour in the silver and gold mines, and eventually, as a result, almost all Spanish industry withered.

Legions of clerks filled in limitless ledgers, and there was an army of tax collectors and calculators, hierarchies of sub-ministers reporting to ministers reporting to the agents of the king. There were shipping agents, overseers and their bosses, issuers of the appropriate forms and those who checked that the forms were completed, and the backup officials who made sure the original officials were not deceiving anyone. When colonial officials made honest mistakes, they were suspected of treason or corruption instead of incompetence or inattention, and they were sometimes sent to Spain in irons to defend themselves—not a pleasant journey, even if they were found innocent. The bureaucratic friction and inertia created an environment where no colonial official would, or could, make decisions without first obtaining written permission from higher authorities in Spain, a process that could take over a year by sailing ship.

Inherent in this structure were the seeds of its downfall. Soon, a majority of the manufactured goods in Spain and the Caribbean were made elsewhere. Spain, in essence, became the unofficial distributor of gold and silver to the rest of Europe, with little industry other than American bullion extraction and transportation. When the gold fleet was waylaid or destroyed, the results were disastrous. As the Spanish colonies grew in sophistication and population, however, they wanted luxury and European manufactured goods and required a dependable means of shipping their local products to market.

Official Spanish policy after 1540 stated that it was illegal for foreigners to trade in the West Indies beyond the line of demarcation stipulated in the Treaty of Tordesillas. The punishment for disobeying the law was death by hanging. All Indies trade, therefore, had to be done with Spain and regulated by the Spanish government. Most manufactured goods had to be imported to Spain from other European nations (the import tax paid), then transported to Seville and officially certified for the New World trade (the certification tax paid). From warehouses in Seville, the goods were then loaded onto an official Indies trade galleon belonging to the annual Flota or Galleones (the export tariff paid, as well as the Averia, the protection cost). Across the Atlantic the goods then went, at great cost and danger, with many clerks and officials overseeing the proper certification. The cargo was unloaded at the docks in either Vera Cruz or Portobello (the New World import duty paid), sold to merchants at the great public markets (transaction taxes paid) and finally shipped to other more distant colonies (import and transfer tariffs paid as the goods crossed colonial boundaries).

In the far-flung Spanish colonies, nearly all luxury goods had to be imported: cloth, gunpowder, weapons, farm implements, cooking utensils, cooking oil, cutlery. By the time these goods had reached the outlying colonies and cities, they had passed through so many customs offices and tariff bureaus that the final cost to colonial merchants was exceedingly high. For example, merchants in Potosi (on the Pacific coast of South America) paid almost forty times the cost in Europe for similar manufactured items: if a local cow was worth approximately two pesos, then a pouch of imported paper with a cost of about one hundred pesos was worth fifty local cows; a sword that cost six hundred pesos was worth three hundred local cows; and a cloak of fine fabric that cost five hundred pesos was valued at two hundred and fifty local cows. This was a breeding ground for dissatisfaction and a black market.

Lured by the potential bonanza, English, French and Dutch merchants, instead of shipping their goods to Spain, began sailing directly for the Caribbean. Spanish colonial merchants were more than willing to participate in the illegal trade, and many secretly smuggled bullion to the foreigners, along with other goods such as hides, cochineal or indigo. The interloping traders charged only a 25 per cent profit margin. Despite the increasing need for manufactured goods in the Spanish colonies, the orders for goods from Spain decreased each year as their prices soared. By the early seventeenth century, smugglers supplied not only almost all manufactured commodities, but slaves as well, to the Spanish colonies. Excessive Spanish taxation and too many middlemen in the transfer of goods had created the market for smuggled, cheaper goods. Once this market existed it was very difficult, almost impossible, to prevent the suppliers from plying their trade, even when they were threatened with violent punishments and perhaps death.

The Spanish government was well aware of the damage to the national commerce (and loss of tax revenue) resulting from these illegal interlopers. It imposed severe penalties on colonial merchants for disregarding trade regulations: imprisonment, heavy fines and loss of official title were common punishments. Foreigners caught sailing in the Caribbean (in the Spanish half of the world) suffered death by hanging or a life of labour in the silver mines. Still, in defiance of the Spanish king’s declarations, in the late sixteenth century, English, Portuguese, Dutch and French mariners and merchants continued to flock to Spanish settlements in the Caribbean—if they couldn’t trade legally, they would trade illegally. As J.H. Parry writes in The Spanish Seaborne Empire, “Spain insisted, in the face of facts, upon an exclusive monopoly of trade, and in the attempts to enforce that monopoly found it necessary to claim in general the right of regulating seaborne traffic in the Caribbean, of defining the courses to be followed by bona fide traders between other European countries and their respective colonies and of stopping and searching foreign ships which deviated from those courses.”

But there was more than just commerce at play here. The French, English and Dutch smugglers were clearly and commonly violating the papal proclamation of 1493 by venturing into the Spanish half of the world in South America and the Caribbean, as well as into the Portuguese half of the world in Africa. The punishments for this behaviour, crossing the line of demarcation, were spelled out in the papal donations, proclaiming excommunication from the Catholic church. However, excommunication was becoming a punishment of diminishing deterrence: large portions of the populations of northern Europe were no longer interested in obeying the words of a corrupt pope, words that had been proclaimed generations earlier; in fact many of them were no longer interested in the words of any pope at any time.

As the sixteenth century progressed, France, England and the Netherlands—either from their direct experience or from observing the ever-increasing coastlines on the many global maps then being created by cartographers—realized that the world was much larger and richer than they had supposed. Yet, according to the papal donations and the Treaty of Tordesillas, these nations had no legal rights to any of the treasure from the Americas or to the spices from the Moluccas. And Spain and Portugal were determined to defend their church-sanctioned monopolies with force. The interlopers were faced with a choice: either become pirates, or challenge the authority of the Catholic church and become heretics. They did both.

King João II of Portugal is shown in this anonymous portrait from the 1500s. A great patron of Portuguese seafaring exploration, he notably declined to sponsor Columbus’s voyage but was later instrumental in negotiating the Treaty of Tordesillas.

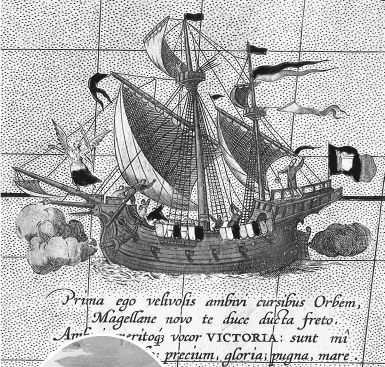

Ferdinand Magellan, shown in this nineteenth-century engraving, led the first circumnavigation of the world between 1519 until his death in 1521, searching for a route to the Spice Islands that fell within the Spanish half of the world according to the Treaty of Tordesillas. His ship Victoria is shown here in a detail from a map by sixteenth-century Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius.

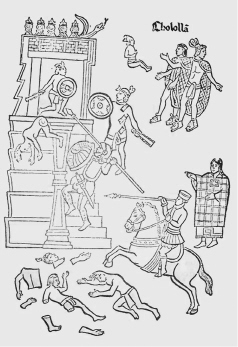

The Spanish conquest of Tenochtitlán in Mexico is brutally depicted in this contemporary engraving.

Hernán Cortés led the expeditionary force against the Aztec Empire. Using a combination of diplomacy, intimidation and deceit, he attacked Tenochtitlán and grabbed the emperor Montezuma as a hostage, leading to the foundation of the Spanish Empire in the Americas.

English mariner Sir John Hawkins, shown in this sixteenth-century portrait, led the first expedition to trade in the Caribbean in defiance of Spanish law, in the Spanish half of the world according to the Treaty of Tordesillas.

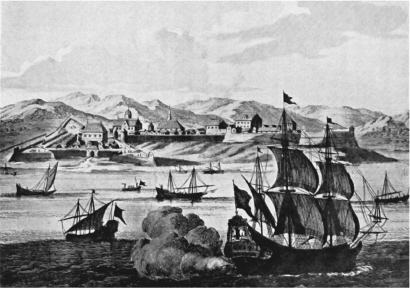

The Spanish port of Nombre de Dios is shown in this sixteenth-century engraving. The town was the destination of the mule trains of silver bullion from Panama City, which was then loaded onto the annual Galleones fleet and shipped to Spain. A frequent target of pirates and privateers, it was first attacked by Francis Drake in 1572.

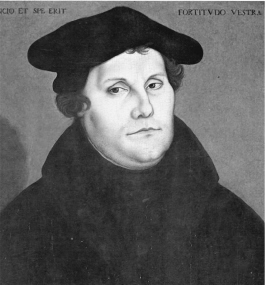

The priest and professor of theology Martin Luther, shown here in this sixteenth-century portrait, challenged what he believed were the corrupt practices of the Catholic church when he nailed to the church door in the German town of Wittenberg his famous Ninety-Five Theses in 1517.

Emperor Charles V is shown in ceremonial battle armour and regalia in this sixteenth-century portrait. The king of Spain and the Holy Roman Emperor, he commissioned Ferdinand Magellan’s voyage in 1519 and pronounced Martin Luther an outlaw.

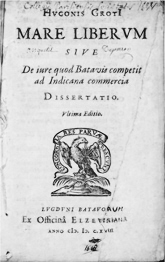

The Dutch lawyer and philosopher Hugo Grotius, the Father of International Law, is shown here in this early seventeenth-century engraving.

Grotius’s anonymously authored Mare Liberum (The Free Sea), published in 1610, was a philosophical and legal challenge to the Treaty of Tordesillas and the papal bulls that underpinned it.