Member of Parliament

In February Diefenbaker got a lucky political break. He was the court-appointed counsel for the defence of Isobel Emele, a woman who was accused of murdering her pro-Nazi husband. Henry Emele was a tyrant who taunted his wife with such pleasantries as, “Hitler will run this country and you’ll learn to like it.” He had also twice been convicted of assaulting her. Isobel was charged with shooting her husband through a hole in the kitchen door with a .30 calibre Remington rifle. She claimed Henry had gone mad and committed suicide.

During the trial, Diefenbaker fixed his steely gaze on each of the male jurors as he listed the reasons why this was not murder. Then he went to the exhibit table, grabbed the Remington, and pointed the barrel towards his own chest. “The length of the arms is what counts,” he said, his voice echoing through the courtroom, “And there is no evidence before this court as to the length of that man’s arms.” But Diefenbaker was far from done. He reminded the jury that Isobel had just cooked dinner for two before her husbands death. “That does not look like premeditated murder to me!”

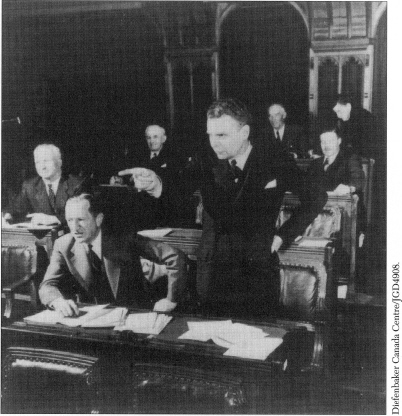

At his House of Commons seat pointing his finger, a move for which Diefenbaker was famous. “You strike me to the heart every time you speak,” Prime Minister Mackenzie King said to Diefenbaker.

The trial ended. The jury returned shortly with two words: “Not guilty.” Applause boomed through the courtroom.

Diefenbaker rode that applause right into his election campaign. He was now seen as an anti-Nazi defender of the downtrodden, exactly what the country needed in wartime.

Diefenbaker switched to political overdrive. He packed in fifty-seven meetings in five weeks, and a fifteen-minute radio broadcast twice a week. He called for a legislated floor price for wheat, which caught the farmers’ attention. He told J.S. Woodsworth, the former leader of the CCF party, exactly what he thought of his pacifism. Diefenbaker travelled by horse and cutter, by train, and by car. He braved blizzards, even spent the night stuck in one. His wife Edna was often by his side and she could break the ice of any conversation.

When Diefenbaker hit the stage he was on fire. His competition asked: “Why would farmers want a lawyer to represent them in Parliament?” Diefenbaker’s supporters fought back with a poster saying: “The Liberals are right. John Diefenbaker is a successful lawyer and does get large fees. Farmers, put your case in his hands. It won’t cost you anything.”

Then the Liberal candidate, J. Fred Johnston, made a mistake. On the Saturday before the election, during a radio broadcast from Regina, he declared, “Are you going to have me as your Member, or are you going to have a conscript? Diefenbaker was a conscript.”

Diefenbaker, who was sitting in the station waiting for his turn, saw red. The suggestion that he had to be drafted by the government into joining the troops during World War I was outrageous. He had volunteered. A few minutes later he strode into the studio, sat himself down in front of the microphone and launched into his final address. It was wartime, so every speech was read and approved beforehand by a monitor. The monitor sat across from John, reading along to be sure Diefenbaker didn’t stray from his subject and somehow encourage enemy forces. When the monitor turned away for a moment, Diefenbaker interjected, “I’ve been in many elections, but this is the first time a deliberate lie has been told by anyone against me. I joined up in 1916 and took my commission. I was invalided home in February 1917. Conscription didn’t come in until after the election in December 1917, the Unionist election that I participated in. Johnston’s statement reflects on everyone who enlisted in the twenty months preceding conscription.” The attempt to defame Diefenbaker backfired, and a number of votes swung his way.

But would it be enough?

Election night, March 26, 1940. John Diefenbaker and Edna are sitting in their home in Prince Albert with several guests, including John’s law partner Jack Cuelenaere. They’re shooting the breeze, unwinding after a gruelling campaign, nervously watching the clock tick down as the votes are counted all across the country. John paces, passing the time by mimicking his opponents. Edna teases him, calling John, “the honourable member.” Later she whispers, “This time you will win, my dear.” At eleven o’ clock John finds out that he’s leading by 150 votes. A good margin, but Diefenbaker doesn’t want to get his hopes up. By midnight he still hasn’t heard the final count – Lake Centre is the only constituency in Saskatchewan in which there are no radio reports. The radio station signs off for the night. Finally, Jack, who is President of the Saskatchewan Young Liberals (Diefenbaker does not mind that his partner has a different political stripe than he does), goes to the phone and contacts his party’s headquarters in Regina. “How are we doing?” he asks.

“Fine,” the man on the other end answers, “except in Lake Centre, and that’s a seat we never expected to lose.”

“You mean to tell me we’ve lost it?”

“Yeah, it’s gone.”

Diefenbaker can barely contain his happiness. He has won by 280 votes.

John Diefenbaker is heading to Parliament.

On May 10th Germany invaded Holland, Belgium, and Luxembourg. France would be next in line, as Panzer divisions moved quickly into place. On the same day Winston Churchill became prime minister of Great Britain.

The next morning, John Diefenbaker sat in a CNR dining car, rattling its way east. He was waiting for his breakfast to arrive. A man joined him and a moment later Edna arrived, slipping into her seat and smiling warmly.

“Where are you going?” she asked the man.

“I am going to Ottawa,” he said.

“Oh, are you going to work for the government?”

“Sort of,” he answered.

“Well, my husband will be of great assistance to you because he is going to be prime minister.”

The man grinned at the charming, attractive redhead. She obviously loved her husband dearly and had grand dreams about him. “Didn’t your husband run quite often?” he asked.

“Five times,” she said, happily. “Just like Robert the Bruce! The spider, up and down, up and down. But my husband will help you.”

“I don’t think he will give me much help,” he said, his eyes twinkling with humour, “because I am a Liberal MP.”

All three of them broke into laughter. Liberal James Sinclair became a fast friend. Edna reminded him four or five times a day that John was going to be prime minister. Sinclair was so charmed by Edna and her support of John that he changed his own plan to postpone his marriage. (His yet-to-be-born daughter, Margaret Sinclair, would later marry a prime minister: Pierre Elliott Trudeau.)

On their trips to and from Ottawa, John and Edna became a political tag team, with Edna often introducing herself to a stranger and John taking over with jokes and stories. It helped them win a number of hearts and a few more votes too.

The Diefenbakers lived at the Château Laurier and John was given a tiny office. Everywhere he went, Edna was at his side, spreading her bubbly enthusiasm through the press gallery. She often spoke of how “my Johnny” was going to become prime minister. Most people just smiled at her and kept their thoughts to themselves.

The clock on the Peace Tower had stopped. It was the 16th of May, 1940, the first day of Parliament. Diefenbaker was haunted by a feeling of foreboding, almost as if there were a supernatural aura in the air. Canadian troops were training for war, and soldiers were dying across the ocean as the Germans pushed their way into France and forced the French and British armies to retreat; it seemed only fitting that the clock had stopped.

Diefenbaker found his seat in the House of Commons, in the third row on the right, surrounded by other Conservatives. Exactly two sword lengths across the floor sat the governing party – the Liberals. Diefenbaker was in awe of the size and the majesty of the House.

Suddenly there was a heavy knock on the door of the Commons.

“Black Rod,” a gruff voice boomed. The door was opened. The Gentleman Usher of the Black Rod took his traditional five steps into the Commons chamber and announced that it was the King’s command that all the honourable members of the House follow him to the chamber of the honourable Senate. At the front of their procession was the sergeant-at-arms, with the mace, a symbol of the authority of the House of Commons, over his right shoulder. The MPs followed him through the wide corridor, where crowds watched. They went under the arch below the Peace Tower and into the Red Chamber of the Senate. There the members lined up along the rail because only one of their number was allowed into the Upper Chamber: the prime minister. Mackenzie King sat at the right of the King’s representative. The Chief Justice of Canada read the throne speech that officially opened Parliament.

It’s a tradition that dates back to the days of Charles I. William Diefenbaker had described it to young John, who now saw it all with his own eyes.

Diefenbaker was in awe of the whole experience of being in Parliament. He explained the feeling in his memoirs: “It has been said that for the first six months a new Member wonders how he ever got elected to such a great institution; thereafter, he wonders how any of the other Members ever got elected.”

Soon he had to give his maiden speech. “I felt that I was in a great vacuum, surrounded by a material of one-way transparency: I could see the others in the House, but they could not see me; and perhaps they could not hear me.” Despite his jitters he was able to get out a short declaration of patriotism and touch on a theme close to his heart. “I spoke of all those who were proud to wear ‘Canada’ on the shoulders of their uniforms in the First World War, and of the sense of nationhood, the concept of citizenship that developed.” He was especially concerned with the separation of different ethnic groups, some considered more Canadian than others. At the time there were 11½ million Canadians, of British, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Chinese, and various other backgrounds.

It wasn’t long before Diefenbaker truly found his voice, using his courtroom tactics in Parliament. Standing tall, seeming tireless, he chastised the government for banning the religion of the Jehovah’s Witnesses under the Defence of Canada Regulations, partially because the Witnesses refused to serve in the war. “I took the stand that their religious views should be recognized, that the ban against them should be removed, and that they should not be required to serve in the armed forces in any combative capacity.”

John rarely read a prepared speech. He preferred to feed off the crowd. Speaking in the Commons chamber he would often place a pile of notes on his desk about his topic and begin his oration. He would pick up the notes, put them down, sometimes refer to them, other times use them as props during a moment of outrage. Occasionally the papers would fly from his hand and somehow, magically, he would find the one with the point he had to make at the exact moment he needed it.

“You know,” he once said, “sometimes I think of a clever phrase during a speech and I start to say it and then I stop and think ‘that’s taking me down a road I don’t want to go’ so I change direction, or don’t finish the sentence. That way, they can’t pin me down. They say: ‘Diefenbaker said so-and-so,’ and they go and look it up and there’s a turn somewhere. They can’t catch me out.”

And he always stood with one hand on his right hip, pushing back his imaginary barrister’s gown.

Often his acerbic wit was levelled straight at Liberal Prime Minister Mackenzie King. “King did not like me,” Diefenbaker wrote, “I presume it was because I took a particular interest in him. I lived and cast my ballot in Prince Albert. He was my member of Parliament.” And it didn’t pay to be Diefenbaker’s member of Parliament. He watched King with a hawklike gaze.

King was a stout man with wispy white hair parted on the side. The top of his head was bald and this made him look slightly like a monk. He was serious, but he had his quirks. He apparently consulted mediums and the spirits to aid in his decisions.

Diefenbaker saw this supernatural side of King in June 1940, when news came over the radio that Paris had just fallen. The leaders of the opposition parties were summoned to the prime minister’s little office behind the Commons chamber. Diefenbaker was included in the session as an adviser. The men were led into an even smaller room and King came out wearing a nightshirt. Dick Hanson, the portly, verbose leader of the Opposition, asked, “Prime Minister, is it true as reported on the facilities of the radio this morning that the great city of Paris has fallen to the Hun?”

Mackenzie King’s face was pale. “I really cannot say,” he answered quietly, “I have not read my dispatches this morning. I worked late on my diary.” The dispatches were sent for, brought in, and read. King said nothing. He got up, his face blank. He stepped toward the fireplace and stood transfixed, staring at the clock on the mantel.

The room was silent.

The prime minister of Canada said nothing. He seemed to be staring right through the clock at the future itself.

Finally, he turned and said, “Diefenbaker, we can’t lose. We shall win the war.”

His prediction, of course, came true.

Nearly a year later Diefenbaker’s barbs and criticisms were getting under the PM’s skin. “What business have you to be here?” Prime Minister Mackenzie King was standing in his office, staring up at John Diefenbaker, anger tingeing his cheeks red. Diefenbaker had come to his office for a briefing, along with several ministers. “You strike me to the heart every time you speak. In your last speech who did you mention? Did you say what I’ve done for this country? You spoke of Churchill. Churchill! Did he ever bleed for Canada?”

Diefenbaker’s anger bubbled to the surface. “What the hell goes on here?” he asked.

No one answered. Mackenzie King actually had tears in his eyes. His face contorted with rage. Then King suddenly grew as calm as Buddha and said quietly, “I regret this, but something awful has happened. The great British battleship, the Hood, has been sunk. Where will we go from here?”

The war waged on, and so did the battle in Canada’s Parliament. Diefenbaker pushed for conscription for overseas service. Only volunteers and professional soldiers were being sent overseas; anyone who had been conscripted by the government remained in Canada. More men were needed at the front, but the Liberals had promised Quebec that they would not send conscripts abroad. It was a promise that didn’t seem fair to Diefenbaker. Then the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor and invaded Hong Kong, which led to the surrender of the Canadian contingent there. Canada’s government had to act.

Instead, they announced a plebiscite for voters to decide about conscription, a move that would take time. The plebiscite went ahead, and the English-speaking parts of Canada were in favour of releasing the government from its promise while the Quebec voters were opposed. King couldn’t decide what to do, so finally he declared that conscripts could be sent overseas and then didn’t send anyone. “The government cannot forever procrastinate,” Diefenbaker declared, “it cannot forever fight this delaying action, if the morale of the people of Canada is to be maintained.” King’s government ignored Diefenbaker.

On February 26, 1942, the Liberals made a decision – one that directly affected thousands of Canadians for the worse. On that day the government decreed by order-in-council that all people of Japanese ancestry be uprooted from their homes and businesses. They were considered a threat to national security, even though many had been born in Canada. Diefenbaker fought against the proposal. “To take a whole people and to condemn them as wrongdoers because of race was something I could not accept. The course that was taken against Japanese Canadians was wrong. I said it over and over again. It was considered unbelievable that I would take this stand.” He fought, mostly alone, and he failed. The Japanese were moved to camps away from the coastal areas.

By the end of the war it was clear the King government had overreacted. There had not been one case of sedition. Nothing to justify this mass hysteria and the uprooting of Japanese Canadian citizens.

Diefenbaker was getting everyone’s attention and making enemies along the way. Occasionally members of the Liberals would mischievously mispronounce his last name. It was the rare radio announcer who could pronounce it properly. Even the Financial Times chose to call him “Campbell-Bannerman” after his mother’s side of the family instead of Diefenbaker.

And the Conservatives were feeling pressured. Arthur Meighen was their leader again, by default because no one else wanted the job. He was unable to win a by-election and lurked outside the House of Commons, trying to direct the party from there.

He soon grew tired of this, and it was decided that the party needed a new leader. “Was not Moses found in the bulrushes?” Meighen asked, “Why should not we go out and shake those bulrushes to find ourselves a leader?”

The Conservatives started “shaking,” and one of the candidates who fell out was John George Diefenbaker.

Unfortunately, a larger candidate tumbled out of the bushes: John Bracken. He was a member of the Progressive party and had been the premier of Manitoba since 1922. He had the backing of Meighen and the old guard of the Conservative party. He would obtain the support of the French Canadians. He was a good speaker and an able politician.

He also couldn’t make up his mind whether or not he would run. If he did run, he wanted the party’s name to be changed to the Progressive Conservatives.

In Winnipeg on December 9, 1942, the Conservatives gathered in an auditorium for their leadership convention. Would Bracken show? Even Meighen didn’t know. Nominations began at 8:00 p.m. Still no Bracken. 8:05. Not a hair of him. Finally, at 8:10, he stormed up to the platform and signed his nomination papers. He received thundering applause from his supporters.

At that moment Diefenbaker knew he couldn’t win.

It became a night of comedy. Howard Green, one of the other nominees, stopped in mid-speech, released the microphone, and fainted at the feet of the people behind him.

Diefenbaker, who was up next, felt oddly nervous. He spoke stiffly as he read from a prepared statement, and sweat beaded his forehead. His voice was high-pitched, he seemed meek and mild. The audience watched in amazement. Where was the fiery orator who constantly poked holes in the Liberals’ mandates?

The ballots were counted the next day. On the first Bracken was in the lead, Diefenbaker third. On the second, Bracken won by a landslide. A motion was made and adopted without any debate. The Conservatives would now be known as the Progressive Conservatives.

Diefenbaker was disappointed, but in a Saskatoon customs office there was a man who felt it even more – William, John’s father. He followed the papers every day and looked for quotes from his son.

He didn’t give up hope though. He continued to tell his co-workers that John would be prime minister. When people teased him, he just replied, “Well, some day. You’ll see.”

Unfortunately, William didn’t get to see. On February 12, 1945 he died, at the age of seventy.

And to make matters worse, Edna was becoming ill. She had been on medication for depression for some time, but she now suffered a complete breakdown and her beautiful red hair fell out in clumps. She was diagnosed with what today would be called mild depression and obsessive neurosis. Her psychiatrist suggested she recover in a sanatorium at Guelph, and Diefenbaker deferred to his medical advice. In those days mental diseases were a source of shame and fear, so John told few people where Edna was. She stayed at the sanatorium for several months and received five applications of electric shock therapy. She was released in March of 1946, apparently cured, though no official report explained exactly what had cured her.

Meanwhile, the Allies were winning the war, but more troops were needed. In 1944 the Liberals faced a conscription crisis. King fired his minister of national defence for demanding 15,000 troops to be called overseas – Quebec would never agree to that. Then, bowing to pressure from disgruntled ministers inside his cabinet, King committed 16,000 troops to overseas duty. It was a complete reversal that kept his government unified. Diefenbaker could only sit back and laugh. In April of 1945 an election was called for June. John returned to the election campaign, promising to fight for the construction of a South Saskatchewan River Dam that would provide hydroelectric power and irrigation to the area. It’ll Be a Dam Site Sooner if John is Elected! was the slogan, coined by his brother Elmer.

The boundaries in Diefenbaker’s riding had been redistributed by the Liberals in an apparent attempt to keep John from coming back to the House. The plan backfired, though, and he won by a landslide. The Liberals were returned to power with a slim majority. The real story of the election was the rise of the CCF, which took third place.

Years passed. The war over, the economy of the country began to click along, and though there was now a Cold War, no real danger threatened Canada. In 1948 Mackenzie King, now in his seventies, resigned the Liberal leadership he had held for twenty-nine years and was replaced by Louis St. Laurent, a well-to-do lawyer from Quebec who had thinning white hair and an almost noble look in his eyes. John Bracken, who had failed to deliver enough votes in the last election, was persuaded to resign the leadership of the Progressive Conservatives.

Once again Diefenbaker stepped up to bat for the leadership. He spoke in Saskatoon, Winnipeg, Vancouver, Toronto, Edmonton, Calgary, Halifax, Saint John, and Montreal in an effort to drum up support. When asked if he would defeat George Drew, his main competition, he answered confidently, “Of course I will.” Then he added, “I mean that seriously, although I would not have said it two weeks ago.”

On September 30th in the Ottawa Coliseum, the Progressive Conservatives met where hockey players battered each other and pucks scarred the rink walls with black. Diefenbaker gave a twenty-minute speech condemning the communist menace in the world and asking his party to inspire Canadians to work even harder to make Canada better.

It wasn’t enough. Drew won on the first ballot, with 827 votes, leaving Diefenbaker in second place with 311. Though he’d gained some popularity, the party members chose a man from the East, closer to the financial powers of Canada.

But John had one more humiliation to endure. “On the night of Drew’s victory, I went up to his suite in the Chateau Laurier. They were celebrating. I was an intruder. I went to congratulate him. I walked into that gathering and it was as if an animal not customarily admitted to homes had suddenly entered the place.”

Dejected, John returned to Prince Albert the next day. His only consolation was the messages of support and well wishes from across the country, including one from Paul Martin, the Minister of National Health and Welfare, who felt John had deserved the leadership.

Parliament was dissolved in April of the next year and another election was declared for June. The Liberals, even with a new, untested leader, seemed inevitable winners. Diefenbaker, who was now a veteran campaigner, went from town to town, his main competition being the CCF. He cruised to another victory, but the Conservatives lost even more seats with Drew at the helm.

John travelled to Australia to attend a conference of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association. While there, he heard reports of a terrible accident in British Columbia: two CNR passenger trains had collided head-on near Canoe River. Wooden passenger cars were crushed by the newer metal cars in a telescoping effect. Twenty-one people, mostly Canadian soldiers on their way to Korea, were killed. Alfred John (Jack) Atherton, a young telegraph operator, was blamed for the crash because he allegedly relayed an improper order. He was charged with manslaughter. John thought the case interesting, and knew whoever acted as defence lawyer would have a tough time.

On December 22, 1950, when John’s plane landed in Vancouver after his return flight from Australia, he was handed a telegram from the family doctor: “Come at once. Edna seriously ill.” He flew to Saskatoon to find Edna in the advanced stages of acute lymphatic leukemia. She had been diagnosed months previously but had chosen not to tell John before he left for his conference.

The only place for John Diefenbaker was beside his wife. When Parliament opened in late January, Diefenbaker’s seat was empty. Paul Martin arranged to have an experimental drug from New York imported, but it proved ineffective. All they could do was wait.

Meanwhile, Edna had received a secret visit from Alfred Atherton, the father of the young man charged with manslaughter in the train accident. Alfred had grown up in Diefenbaker’s riding and had talked his way in to see Edna.

“Alfred Atherton has been to see me,” she told John. “Everyone in the CNR is running away from responsibility for what appears to have been a grievous disregard for human lives.” She then told John to take the case. He explained that he’d have to pay the fifteen-hundred-dollar fee to join the British Columbia bar. He had his duty as an MP to consider, and she was so sick, how could he leave her? Edna didn’t waver. “Please John, I told him you would take the case. Jack Atherton is innocent, but his life will be destroyed if he does not have you to defend him. Please take it… for my sake.”

“All right Edna,” he said. “I will see young Atherton and see if I can win the case.”

In early February, Edna Diefenbaker, the woman who had accompanied John to so many meetings, who had driven their car while he slept or prepared his speeches, died. She was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Saskatoon. The press across the country remarked on the sad loss of Edna, whom they called an unelected member of Parliament. John felt abandoned and deeply anguished.

But he had a court case to win.