Leader of the Opposition

“Are you ready for your examination?” The Treasurer of the Law Society stared across the table at Diefenbaker. John had paid the fifteen-hundred-dollar fee to join the British Columbia bar. He now had to take an exam. If he failed, he would have to wait to re-apply and would miss the trial.

“I’m ready.”

“Are there contracts required by statute to be in writing?”

John considered the question. Was this the beginning of some sort of legal trap? “Yes,” he said.

“Name one of them,” the Treasurer boomed.

These three photographs capture Diefenbaker the orator,

in the middle of a fiery speech.

John took another moment to think. “A land contract.”

The treasurer nodded and suddenly smiled. “You have passed your examination and it will interest you to know that you are the first in the history of the bar of this province to have passed with a mark of one hundred per cent!”

John could only leave, shaking his head and laughing. Within a few days he was in court.

May 9, 1951, Prince George. The Crowns case against Jack Atherton was simple: the young telegrapher had forgotten to include two words in his message to the conductor of the troop train: “At Cedarside.” This would have told the conductor to wait at a siding while the eastbound passenger train passed. Atherton insisted he had included the two words.

Diefenbaker called no witnesses. In fact, he sat silently through the beginning stages of the trial. Part of this was due to exhaustion: emotionally he was worn out and still suffering deeply from Edna’s death. Studying hard for the case hadn’t helped things.

At one point during the trial, his assistant, John Pearkes, whispered, “Everyone’s thoroughly fed up. They thought you were a good counsel and you haven’t said a word.”

Diefenbaker remained tight-lipped. He continued in the same pattern, watching the Crown counsel, Eric Pepler, who was an ex-colonel. Pepler was missing a leg, but he still carried himself with the air of a military man. Witnesses came and went. Still no questions from Diefenbaker.

Then the Crown called an official from the CNR, the man who had decided the order of the cars on the train. Diefenbaker finally stood, and the jury waited in anticipation. “I suppose,” Diefenbaker announced in a loud, serious voice, “the reason you put these soldiers in wooden cars with steel cars on either end was so that no matter what they might subsequently find in Korea, they’d always be able to say, ‘Well, we had worse than that in Canada.’” As one, the members of the jury sucked in their breath. The galley stood in shock. The Crown counsel glared at Diefenbaker. Finally the judge said Diefenbaker’s outburst was improper: it was a statement rather than a question.

“My Lord,” Diefenbaker answered, somewhat haughtily, “it was made clear by the elevation of my voice at the end of the sentence that there was a great big question mark on it. This man is an intelligent man. Right up at the top of the hierarchy. It’s a long question, but it won’t be difficult for him. He’ll be able to break it down.”

An argument broke out between the judge, Diefenbaker, and the Crown counsel. Was it a proper question? The Crown counsel kept getting hotter and hotter under the collar. “I want to make it clear,” Peplar said, his military-trained voice cutting through the courtroom like he was giving an order, “in this case we’re not concerned about the deaths of a few privates going to Korea.”

He meant that the court case wasn’t about the death of the privates, but only concerned the four train crew members had died. Diefenbaker leapt in, gleefully, sensing the soft spot in the Crowns case. “Oh! Colonel! Oh!” he hissed, glancing over at the jury to be sure they were watching. “You’re not concerned about the killing of a few privates? Oh, Colonel!”

There happened to be two veterans from the First World War in the jury. One turned to the other and said, loud enough so the whole courtroom could hear, “Did you hear what that said?”

It was the turning point. For the rest of the trial Diefenbaker pretended to be deaf as a post. Every time the prosecutor asked a question, Diefenbaker would say, “I didn’t quite hear you, Colonel.” The jury became colder and colder towards the Crown and its case.

During his closing arguments Diefenbaker told the jury about a previous incident where a seagull had dropped a fish on a snow-covered line and interrupted a message. Even snow could cause a short in the line. He knew there had been a heavy snowfall the night before the crash, which would have left snow on the telegraph wires. A pause, a moment of silence, was not unusual in the transmission of a message, he claimed. He concluded by saying: “No small men shall be made goats by the strong or the powerful in this country.”

The jury acquitted after just forty minutes, and Jack Atherton’s mother, dressed in black and sitting in the front row of the galley, sobbed in relief.

The case made headlines across the country. The Prince George Citizen even printed the words of a prominent B.C. Liberal who said about Diefenbaker: “For a Conservative, that man seems pretty intelligent.”

The accolades were moving, but it was more important to John that he had fulfilled his promise to Edna.

By 1952 the population of Saskatchewan was declining; in fact, it had dropped by 64,000 since 1941. This would have had little bearing on John, except it meant that parliamentary seats in the province would have to be redistributed. There would be one less member going to the House of Commons from Saskatchewan. The job of changing the boundaries was handled by Jimmy Gardiner, who had once been Liberal premier of Saskatchewan but was now the minister of agriculture in the Liberal Federal cabinet. He had no love for Diefenbaker.

Gardiner sliced up Lake Centre constituency with the skill of a surgeon, taking out ninety townships who had voted strongly for Diefenbaker. Then he stitched on Moose Jaw and parts of Regina, two Liberal and CCF strongholds. The Liberals definitely didn’t want Diefenbaker back. If he ran in Lake Centre he was guaranteed to lose.

For every action there’s an opposite and equal reaction, even in politics. Diefenbaker’s supporters heard about the changes and got mad. Then they got even.

Fred Hadley, one of Prince Albert’s leading Liberals, invited Diefenbaker to forget about politics and go fishing. You never had to ask John twice to go fishing! They went north to Lac La Ronge along with Elmer Diefenbaker and Tommy Martin, a Social Credit businessman. They were listening to the American Democratic presidential nomination on the radio when Fred Hadley suddenly popped the question to Diefenbaker: “Why don’t you run in Prince Albert?”

“Oh,” John replied, “the idea is ridiculous.” The group pressed him and promised to help, but John wouldn’t decide. They spent the next couple of days fishing and then John returned to Ottawa.

In his memoirs, Diefenbaker explained what happened next: “When the Session recessed in December, I went West. I was met at the airport by Fred Hadley and Ed Jackson (a leading CCFer). Without my knowing of it, Hadley, Martin, and Jackson had been instrumental in organizing a series of Diefenbaker Clubs, made up of members or supporters of all political parties except the Communist, in Prince Albert constituency. The executive reflected the membership at large; it was a mixture of well-known Liberals, CCFers, Social Crediters, and Conservatives. Their slogan: The North Needs John.”

Voters rallied to the cry, for they knew John’s views on northern development, agriculture, and unhyphenated Canadianism. Nationally, the Conservatives were handed an issue on a golden platter: the Currie report. This was a detailed look at irregularities in domestic military spending. There were over a hundred improprieties. The claim of fraud that immediately stuck in the public’s mind was that horses were hired and placed on the payroll of the military. Though this was never proven, it left the Liberal government looking like stooges.

The next election was called for August 10, 1952. In Prince Albert, John Diefenbaker won by just over three thousand votes. Three thousand and one to be exact.

Jimmy Gardiner’s “Jimmymandering” had failed.

And, unbeknownst to most of John’s relatives and friends, he had become engaged. Purely by a chance of fate, in Ottawa, he had met Olive Freeman Palmer, the minister’s daughter he had once asked on a date in 1921. Her husband had passed away, leaving her with a daughter. She was now a senior civil servant with the Ontario Ministry of Education in Toronto, a strong, serious woman who immediately lent her support to John’s career and his personal life. “When we met again after all the years,” John later explained, “we started to talk about the things we talked about so many years before.” The talking led to love and a secretive courtship. In December of 1953 John and Olive had a small, quiet marriage in the study of the Reverend Charles G. Stone, in Park Road Baptist Church, Toronto. The wedding was followed by a brief honeymoon in Mexico.

By 1955 the Liberal government had grown grey and tired. Louis St Laurent was drained after seven years in office, and CD Howe, his most prominent and outspoken minister, had grand plans: he wanted to build a natural gas pipeline from Alberta to eastern Canada. All parties thought it was a good idea, but the Conservatives insisted it be built by a Canadian company (the government was in negotiation with an American company) and the CCF wanted the pipeline publicly owned.

This was too much argument for Howe. He was in a hurry. He served notice of closure before the bill could be debated. The howls of outrage echoed up and down the halls of the Parliament Buildings. Democracy was all about debate. This was a dictatorship, some cried. For five weeks straight the opposition parties banded together to slow down the work of Parliament. As the roar grew, the prime minister sat reading a book. The bill was passed, but the government looked like bullies now.

Unfortunately, the Conservatives were hurting too. George Drew, their leader, had to withdraw at the urging of his wife and doctor. He was feeling the effect of too much strain and exhaustion and was now ill with meningitis. The party would need a new leader.

It was pretty obvious who it should be. Diefenbaker had won the nationally acclaimed Atherton law case. He was the most visible of all the Conservatives, constantly lashing out at the government. National opinion polls gave him the leadership in a walk. The backing of other party members swung behind him. And more importantly, funds began to flow in to his campaign from Conservative supporters across the country.

Diefenbaker announced his candidacy with these words. “I have not sought for myself and I shall not seek the high honour of leadership. But if Canadians generally believe that I have a contribution to make, if it is their wish that I let my name stand at the leadership convention, I am willing.”

He was playing coy. He knew the party wanted him. And he had faith the voters wanted him too.

December 13, 1956. In the Ottawa Coliseum, the scene of John’s previous defeat, 1472 delegates are gathered in their seats, badges on their chests. They are letting balloons go and waving banners and placards: Youth for John Diefenbaker, Manitoba for John Diefenbaker, Ontario for John Diefenbaker. It is hoopla at its finest, an American-style political celebration. You’d think someone had just scored a game-winning goal.

Then a voice booms, introducing, “a candidate for the leadership of this great party and the future prime minister of Canada, John Diefenbaker of Prince Albert, Saskatchewan!”

“John… John… John,” his followers chant.

The next day, Diefenbaker wins on the first ballot, with more votes than both his opponents put together. The delegates jump to their feet. Wave after wave of Diefenbaker signs are thrust skyward.

Diefenbaker, dressed in a navy suit and wearing a red rose, comes to the front. His competitors, Donald Fleming and Davie Fulton, are at his side in a show of solidarity. They raise John’s arms as if he has just won a championship boxing match. Between them is a man who has battled in the court and in the House of Commons. His eyes are ablaze. He is sixty-one years of age, but he feels forty.

Diefenbaker strides to the podium and, feeding on the crowd’s adoration, he promises, “We will be the next government. We have an appointment with Destiny.” He ends his speech by saying, “I will make mistakes, but I hope it will be said of me when I give up the highest honour that you can confer on any man, as was said of another in public service: ‘He wasn’t always right; sometimes he was on the wrong side, but never on the side of wrong.’ That is my dedication; that is my humble declaration.”

There is only one sour note. Upset that Diefenbaker hadn’t chosen someone from Quebec to second his nomination, a good many of the Quebec delegates walk out of the Coliseum when Diefenbaker’s election is declared unanimous.

Diefenbaker immediately began touring across the country and making speeches. A wave of hysteria – a Diefenmania – swept the party. Diefenbaker thundered like a prophet about the downfall of the smug Liberal government. He became known affectionately as “Dief” and “Dief the Chief.”

And in the House of Commons “the Chief” took charge. He raged over taxation and low pensions for seniors. He told the government they needed to provide more help for the poorer provinces. At one point during debate he rose, pushed aside his chair to make room, and stood with his right hand on his hip. “What does the government do?” he asked, his voice booming. Out would launch the accusing finger, pointing straight at Louis St Laurent like he had caught some petty thief in the middle of a crime. “It continues its policy of being resolute in irresolution.”

By the time the election was called, support had snowballed. It’s Time For a Diefenbaker Government was the Conservatives’ slogan. No longer were they the Conservatives who had been tainted by their years in office during the Dirty Thirties. They were brash. Confident. They had a new man to lead the charge, a man who might even be bigger than the party itself.

And Diefenbaker had refined his message for the Canadian people. Canada needed a new vision, like the vision of the railway that bound the country together so many years before. The Conservatives would bring that new vision to reality, by launching a national policy of development for the northern areas – the New Frontier Policy. “The North, with all its vast resources of hidden wealth – the wonder and the challenge of the North must become our national consciousness.” Diefenbaker had seen the North for himself, fished her waters, flown over hectare after hectare of trees and resources. It was all there for the taking.

The Conservatives would also reduce taxes, get fair prices for farmers, and increase old age pensions. A golden age was coming, but it couldn’t be ushered in by tired, old Liberals who had held power so long they had forgotten how to dream up anything new.

With each speech the crowds grew larger and louder. Diefenbaker stopped everywhere, with Olive constantly beside him. He was shaking hands, making speeches, making jokes. He won the hearts of the people. He was one of them. From the Prairies, not some bureaucrat. Things would change if we voted for him.

Of course, to win the election was still unthinkable. But his last prediction in the town of Nipawin, Saskatchewan was this: “On Monday I’ll be prime minister.”

The crowd went crazy.

June 10, 1957, election day. The streets of Prince Albert were slick with a light rain. The weather was cool – the kind of day where you wrapped your coat tightly around yourself. John was up early, and he and Olive walked the three blocks to the nearest poll to mark an X beside his own name. Afterwards, he wandered up and down Central Street shaking hands and greeting old friends. He had an uncanny knack for remembering people’s names, even if he hadn’t seen them for years.

In the afternoon he had a nap.

Then he and several guests sat in front of the Diefenbakers’ radio, tuned to CBC. The results came flooding in. The Conservatives had gained in each province. Even better news was that eight current ministers had lost their seats, including CD. Howe. “These Cabinet ministers are going down like flies,” John said, grinning. He couldn’t help but grow more excited and hopeful. In his home-town riding he won by 6500 votes. It looked like the Conservatives would win a minority at least.

Unfortunately there was no link to network television in Prince Albert. If they won, or lost, John would have to make a speech. So he caught a Canadian Pacific flight to Regina and listened to the pilot’s radio for results. Dief had two speeches in his hand – one if he won, the other if he lost. Halfway to Regina he drew a line through the loser’s draft. Not all the polls had reported in, but he had won a minority government. Twenty-two years of Liberal rule had come to a crashing halt.

He landed in Regina and was ushered to the TV studio. Staring straight into the camera, he fixed all of Canada in his gaze. He spoke solemnly: “I now give you my pledge that we shall stand by the principle which we have enunciated during this election campaign. Our task is not finished. In many respects it has only just begun. I am sure that you will agree with me that conservatism has risen once again to the challenge of a great moment in our nation’s history. In answering that challenge we have done our best to express in word and action what we believe to be the will of millions of Canadians from the Atlantic to the Pacific.”

The next day Louis St. Laurent phoned to offer congratulations and say he would be resigning. John Diefenbaker was assured of being the thirteenth prime minister of Canada.

John drove to Saskatoon to visit his ailing mother at the University Hospital. He was bubbling with excitement – one part the sixty-year-old man, the other part the nine-year-old boy who had declared his dream so long ago. When he told her the news she said, “This is quite a thing, isn’t it?” Then she lectured John: “Do not forget the poor and afflicted. Do the best you can as long as you can.”

And she never mentioned the fact that he had become prime minister to him again. It was not in her Scottish nature to brag about his deeds.

But the feeling of disappointment caused by his mother’s reaction did not last long. These were heady days. He was the prime minister-elect. People wanted his time. His phone rang constantly. He had mountains of work.

So he did what any man of the North would do in this situation. He went fishing on Lac La Ronge.

At the end of the day, he ambled off the boat and held up his catch for the onlookers.

“Not much of a fish you caught there, eh?” one of his friends asked.

“No,” Diefenbaker replied, grinning, his eyes alight with a mischievous glint. “I caught the big one yesterday.”

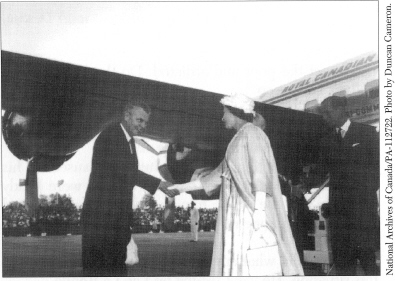

John Diefenbaker greets Queen Elizabeth II

and Prince Philip in 1959.

John & Olive Diefenbaker take a moment to enjoy the garden at 24

Sussex Drive. “It’s a fairy place,” he tells his mother in a letter.