Follow John!

Take everything that had happened in Diefenbaker’s previous election campaign and multiply it by ten. This time the audiences were ten times louder. The vehement speeches were ten times longer. Diefenbaker’s 1958 campaign actually worked voters into a frenzy. Crowds broke down the doors at the Winnipeg Auditorium and filed into a building already stuffed to the rafters with people. The trains and planes of the Conservative party passed through every region of Canada. Diefenbaker shook thousands upon thousands of hands.

It was winter, traditionally the worst time to campaign, but Diefenbaker warmed the hearts of Canadians with his fiery speeches. He sounded more and more like a prophet: he spoke glowingly of The New Frontier Policy. The North would be opened. It would bear riches. There would be roads to these new resources. And jobs.

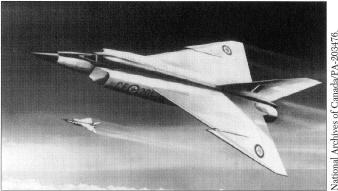

The Avro Arrow, a supersonic, delta-winged interceptor aircraft, designed and constructed by Canadians. The Diefenbaker government’s decision to cancel the Arrow was highly controversial.

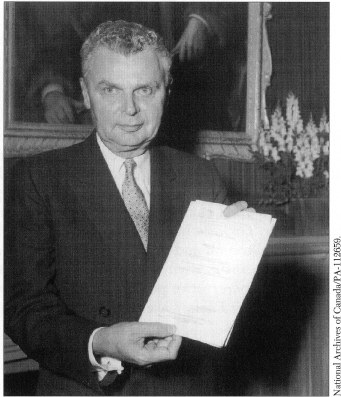

Diefenbaker proudly displaying the Bill of Rights.

John was fond of saying, “I don’t campaign, I just visit with the people.” This was the biggest visit in Canadian history, and the people seemed to enjoy their guest.

“One Canada,” he told the crowd in Winnipeg, “One Canada, where Canadians will have preserved to them the control of their own economic and political destiny. Sir John A. Macdonald gave his life to this party. He opened the West. He saw Canada from east to west. I see a new Canada – a Canada of the North! This is the vision!”

When he was finished, he strode through the crowd. People kneeled and kissed his coat. Not one person. Not two. But many. With tears in their eyes. Canadian politics had never before been like this.

Again and again it happened: people lined up to touch the hem of Diefenbaker’s coat. Thousands waited to shake his hand and at times it became so tender he couldn’t even use it. In Montreal his train was mobbed, and the crowd wouldn’t even let him get out of the car. In Edmonton a blind woman pressed against him in a hotel lobby, saying: “Oh, Mr. Diefenbaker, it’s so wonderful to hear your voice.”

Diefenbaker had hit a political gold mine. He had become Goliath, and the Liberals didn’t even have a stone to throw at him. His posters summed his whole campaign up in two words: Follow John! His wife was beside him, his party behind him. And the people were drawn to him like he was the Pied Piper. In Toronto he remarked on the effect his “visit” with the country was having: “Everywhere I go I see that uplift in people’s eyes that comes from raising their sights to see the Vision of Canada in days ahead. Instead of the hopelessness and fear the Liberals generate we have given faith; instead of desperation we offer inspiration.”

He voted in Prince Albert on election day March 31, 1958, then spent his time mainstreeting, seeing familiar friends and faces, and never missing a name or a chance to share an anecdote. It was cold and drizzly, but the rain sizzled when it hit his skin. Eventually he retired to a room in the Avenue Hotel, where he relaxed in his underwear and read Abraham Lincoln’s biography as the returns came in.

The victory was stunning. The people had followed John right into their voting booths. The Conservatives had won 208 seats, the Liberals 48, the CCF 8. It was the largest political victory in Canadian history. And at home John mopped up with 16,583 votes – the biggest vote ever recorded by any candidate in Prince Albert.

John Diefenbaker had his majority government. He had control of the reigns of the country. Now everyone waited breathlessly to see where he would steer them.

He chose his cabinet ministers, but due to bad advice, none of the new Quebec members were brought into a cabinet position. In Quebec the voters have a long political memory, and this slight would not be forgotten come the next election.

Diefenbaker faced another problem: there were now so many Conservatives in Parliament that he couldn’t keep them all occupied. Many had to be left out of appointments. He didn’t even know everyone’s name; in fact, he hadn’t even met some of the Conservative MPs before. How would he organize such a force into a well-run government? Their numbers were so large they dominated Parliament and sat on both sides of the House, with the opposition parties huddled to the left of the Speaker.

Unemployment reared its ugly head and the Diefenbaker government responded by expanding public works grants and tacking a six-week extension onto unemployment insurance benefits. And they began one of John’s pet projects, legislation of a Bill of Rights for Canadians. Next came transportation and grain-growing subsidies intended to aid the farmers.

The closely cropped moustache on Donald Fleming’s face began to twitch. As finance minister, his job was to keep a tight grip on all government spending. He began to make noises about the deficit.

Meanwhile, the Cold War was getting hotter: the U.S., Britain, and the Soviet Union were flexing their military muscle by testing their nuclear weapons. They also worked on long- and medium-range missiles, which, if a war started, would be flying both ways over Canadian air space. And the Soviet Union hinted that it planned to absorb Berlin into the Union. At the time, half the German capital was controlled by the Allied Forces and half by the Soviets. It was the most likely place for war to start.

In order to improve relations with the outside world, Diefenbaker departed on a world tour of Commonwealth countries. His first stop was London, and a meeting with Prime Minister Macmillan. Diefenbaker was well received by the press and by the six thousand people who packed London’s Albert Hall, where he spoke about a new, greater destiny for the Commonwealth. Next he flew to Europe, where he met with Charles de Gaulle, president of France, and then the Canadian prime minister was off to Germany and Rome.

While in Rome, John and Olive met with Pope John the XXIII. He too had just been elected.

“Are you a Catholic?” the Pope asked. Diefenbaker admitted he was a Baptist.

“That’s all right,” said Pope John, “We are all going to the same place.”

Diefenbaker couldn’t help but be a little cheeky: “So how does it feel to be Pope anyhow?” he asked.

Pope John laughed. “Well, here I am near the end of the road and on top of the heap.” Diefenbaker knew exactly what the pope meant.

The Chief continued on to Pakistan, India, Ceylon, Malaya, Australia, and New Zealand to meet with leaders in each country.

Twelve thousand feet above the Pacific Ocean, John and Olive celebrated their fifth wedding anniversary. All was quiet when the prime minister returned home.

It wouldn’t stay that way for long.

Crawford Gordon, stinking of scotch, held a lit cigar in one hand and beat his other hand on the prime minister’s desk. He was a large, confident man, used to getting his way. He loudly demanded a guarantee that the Avro Arrow supersonic interceptor program would go ahead.

“You’re going to hurt your hand,” Diefenbaker pointed out. He couldn’t believe that Gordon, the Chief Executive Officer of A.V. Roe Canada, was telling him, the prime minister, what to do. The government wouldn’t pour any more money into the Avro Arrow.

“My stockholders are eighteen million Canadians,” Diefenbaker barked.

Crawford wasn’t impressed. He continued his tirade, waving his cigar and pounding his fist. Diefenbaker threatened to have him removed by force. Again, Crawford demanded a guarantee about the Arrow.

“It’s off,” Diefenbaker said, calmly.

Gordon spun on his heel and stomped out of the office, cigar ash caught in the swirling air. Soon his face was white as a sheet. He knew in his heart the Arrow would fly no more.

It was a dramatic confrontation between the prime minister and one of the most powerful industrialists in the country. Crawford Gordon and A.V. Roe had built the CF-105, more commonly known as the Avro Arrow. It was a supersonic, delta-winged interceptor aircraft, designed and constructed by Canadians to stop invading Soviet bombers before they reached populated areas. The Arrow, slick and beautiful, was regarded as the world’s most advanced fighter and proof that Canadians had the “stuff,” the technological know-how to build something great.

Unfortunately, the Soviet Union had already launched their first intercontinental missile, and they had shot Sputnik, humankinds first satellite, into orbit. The space age was here. Military theorists now predicted the Soviets would be sending intercontinental missiles through the skies, not bombers. The Arrow was already outdated and massively expensive. It was projected to add four hundred million dollars a year to the defence budget. And, worse, the government couldn’t find any other countries to buy the interceptor.

“There is no purpose in manufacturing horse collars when horses no longer exist,” Diefenbaker said. The cancellation of the Arrow hadn’t been an easy decision for John. “I had listened to the views of various experts; I had read everything I could find on the subject; I thought about it constantly; and, finally, I prayed for guidance. The buck stopped with me, and I had to decide.”

On the morning of February 20, 1959, Diefenbaker announced the immediate cancellation of the Arrow program in the House of Commons.

By 4:10 p.m. a call came across the Avro plant loudspeakers. It was Crawford Gordon himself. “Notice of termination of employment is being given to all employees of Avro Aircraft and Orenda Engines pending a full assessment of the impact of the prime minister’s statement on our operation.” The company immediately dismissed 14,548 employees. The mass firing was designed to make headlines in the media in order to embarrass the government.

Neither the Conservatives nor A.V. Roe Canada had any plans for alternative programs that would keep this well-trained force of technical workers in Canada. Many went to the United States. The sudden loss of so many jobs was a hard blow to the local economy. Not a good thing to happen in vote-rich Ontario.

Later the existing Arrows were dragged out of their hangars and blowtorched to scrap under the watchful eye of the Department of National Defence. For many years this dismemberment was blamed on Diefenbaker as retribution for Crawford Gordon being such a thorn in his side. “I was the one who was excoriated and condemned,” Diefenbaker later wrote. “Every effort was made to place the responsibility entirely on me. I was even reviled for having had the completed Arrow prototypes reduced to scrap when I had no knowledge whatsoever of this action.” Mr. Sévigny, who was associate minister of defence, said in The Ottawa Citizen, “Frankly, old Diefenbaker was being blamed for something he didn’t do. He never gave an order like that. It’s logical that it was Mr. Gordon who did it. He was the one who was actually in charge of the show. He was the man responsible.”

Either way, the Arrow was gone. Canadian pride had been stung. A month later Diefenbaker announced that Canada would place two batteries of U.S. Bomarc anti-bomber missiles at bases in North Bay, Ontario and La Macaza, Quebec. The Americans would pay for the missiles. Canada would look after the support costs. It would be some time before the batteries were built, but the nuclear-tipped Bomarcs would be vastly cheaper than the Arrow.

What wasn’t cheap was the political cost of cancelling the Arrow. It was an end to any voter’s innocent belief that the Conservative government could magically turn everything in Canada around. John Diefenbaker, the man who had promised a new dream to Canadians, had been forced to burst the bubble on a smaller Canadian dream.

Diefenbaker and his government still had plenty of promises to fulfill. John succeeded in introducing the Canadian Bill of Rights for the second and final time on July 1, 1960. The bill said: “I am a Canadian, a free Canadian, free to speak without fear, free to worship God in my own way, free to stand for what I think right, free to oppose what I believe wrong, free to choose who shall govern my country. This heritage of freedom I pledge to uphold for myself and all mankind.” It was a lofty bill, a legal document that enshrined equality for all Canadians, no matter their ancestral background or religion. It was passed with unanimous approval on second reading and on August 10th was proclaimed into law.

Legislation had also been adopted to give the vote to treaty Indians and Inuit. The Aboriginal Peoples now had a say in Canada’s future. Diefenbaker’s fight for the underdog continued.

John Diefenbaker lifted up his head. Before him, seated in the United Nations Assembly, were the gathered leaders and representatives from across the world. In John’s hands were several sheets with scribbled notes on the typed text. He took a deep breath. He was about to launch into a speech that would be heard worldwide.

Only the night before a very different man had stood in the same spot. Shorter, bullish, and balding, Nikita Krushchev had risen from peasant beginnings to Soviet premier. He delivered a blistering 140-minute denunciation of western colonialism and American military imperialism. Krushchev defiantly declared that he would no longer continue disarmament negotiations unless the secretary general of the United Nations (UN) was replaced by a triumvirate and the UN headquarters moved from New York to Geneva or Vienna. The triumvirate would, of course, include Krushchev himself.

Diefenbaker was the first of the western leaders to reply to Krushchev’s demands. He started slowly, saying he had come prepared to discuss problems openly, but that was apparently not in Krushchev’s plans. Then Diefenbaker leapt to the attack. “How many human beings have been liberated by the U.S.S.R.?” he demanded, using every nuance of his trained voice. His words echoed in the assembly. “Do we forget how one of the postwar colonies of the U.S.S.R. sought to liberate itself four years ago and with what results?” This brought to mind the failed Hungarian uprising of 1956. “What of Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia? What of the freedom-loving Ukrainians and many other Eastern European peoples which I shall not name for fear of omitting some of them?” Krushchev was not in his seat, but the chief representative of the U.S.S.R., Valerian Zorin, walked out halfway through Diefenbaker’s speech.

Diefenbaker continued on, unaffected. “What good can there come from threats to rain rockets or nuclear bombs on other countries, large or small?” He ended with an appeal to peace. “We are not here in this Assembly to win wars of propaganda. We are here to win victories for peace.”

When he was finished, Moscow radio and the Russian paper Izvestia denounced the speech. Krushchev himself was not unaffected. Diefenbaker later had a chance meeting with the Soviet premier: “I too experienced Krushchev’s odd behaviour. When he passed me in the corridor following my speech, he stepped sideways and nearly knocked me down with his shoulder.”

Western leaders applauded Diefenbaker’s speech. The British prime minister and President Eisenhower both congratulated John.

It was a shining moment on the world stage. Soon that stage would have one more important player. For, on November 8, 1960, John Fitzgerald Kennedy was elected the thirty-fifth president of the United States.