AN ONION is an onion. But when Rabano Mauro explains to us, in one of those symbolic, allegorical, and figurative interpretations that weave through his book De universo, that onions and garlic “signify the corruption of the mind and the bitterness of sin” because “the more one eats them, the greater the torment,” an onion has evidently become something other than an onion.1

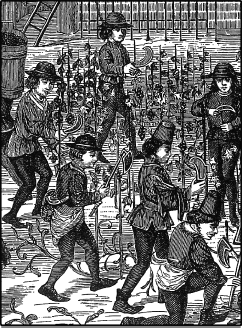

Onions also became something else when Giovanni Italico, the biographer of Odo, abbot of Cluny, relates his encounter with an aged pilgrim during the return journey to Rome in the company of Odo. The old man had on his back a sack full of onions (along with garlic and leeks), and Giovanni, bothered by the stench, moved to the other side of the path. The intense odor of onions thus became the mark of peasant taste, which the fastidious monk found revolting.2

The onion (once again associated with garlic and leeks) also became something other than an onion when Liutprando, bishop of Cremona, was sent to the court of Constantinople as ambassador of Emperor Otto I of Saxony and viewed the custom of eating such foods as a sign of cultural inferiority. To indicate the nobility and prestige of his emperor, Liutprando pointedly rejected these odorous vegetables, unlike the “king of the Greeks,” Niceforo Foca, who demonstrated his baseness by “eating garlic, onions and leeks.”3

This intersection of symbolic implications—economic, social, political, and moral—gave rise to a tangle of meanings about our onion that went beyond the dimension of nutrition to that of language. The alimentary system in all societies works, in fact, like a veritable code of communication, regulated by conventions analogous to those that give connotation and stability to verbal languages. This ensemble of conventions that we call “grammar” replicates itself in alimentary systems; the result is not a simple compilation of products and foods or a more or less casual assemblage of elements but rather a structure inside of which every element acquires a meaning.4

Starting from this idea, it is possible to propose a few thoughts on European alimentary systems during the Middle Ages and on the modalities of their linguistic dimension, employing the double meaning of internal structure (the organization of an alimentary system within rules of usage analogous to those of verbal systems) and external projection (the use of the alimentary system as a means of social communication). I will concentrate on the first aspect by asking this question—particularly with regard to the centuries of the high Middle Ages: What was the grammar of food, and what were the vocabulary, the morphology, the syntax, and the rhetoric that constituted it?

The lexicon on which this language is based necessarily consists of the repertory of available products, plant and animal, like the morphemes (the basic units) that constitute the words and the entire dictionary. It is therefore a lexicon that defines itself in relation to local situations and is thus, by definition, variable—and all the more so during the high Middle Ages when the dynamic between the forest economy and the domestic economy, alternately integrated and complementary, anticipated broad discrepancies in both directions, for plants as well as animals. Animals that seem to us entirely domestic, such as oxen, also existed then in the wild; animals that seem to us wild, like deer, were then also domesticated, not to mention pigs and boars, hard to distinguish by their appearance and their behavior.5

This variable and, in a manner of speaking, experimental factor gave rise to subsequent social and cultural variants. The resources of the uneducated had a particular appeal to the aristocracy, which enjoyed the forest as the site of the hunt and of the confrontation with wild animals (in opposing6 and also imitative terms). Even hermits appreciated the uneducated, seeing in them a simulacrum of edenic innocence and providential alimentation—in this case, vegetarian.7 The monastic vocation, preferring the domestic to the wild (in agricultural as well as pastoral practices)8 opted instead for peasant culture.9

In this variety of interests and outlooks, a few basic elements can be identified. The most important is the prevalence, primarily in the alimentary lexicon of the peasant population, of what in the documents is called bestie minute (small animals): pigs or sheep, raised for various alimentary uses. The pig is the ideal animal for meat and the ewe the animal for milk (or, more precisely, for cheese because that was the normal purpose of the milk). In only a few regions, determined by the environment (primarily in regions of forest or meadow) or by cultural traditions (largely in the Roman tradition), are sheep also important as a source of meat. The presence of cattle in the alimentary repertory remained minor, even if archeological data (rather than written sources) attribute greater importance to cattle raising during the Roman era.10

More common is the importance, during the high Middle Ages, of animals raised in conjunction with the development of forest-pastoral activities. Within the same context, fishing, practiced in the inland waters that are an essential part of the uncultivated landscape, was a positive contribution to the economy, whereas fishing for sea fish, which had been highly productive and commercial in Roman times, was a decidedly negative contribution in the Middle Ages and began to disappear from the alimentary horizon. Even in Ravenna, on the Adriatic seacoast, the regulations of the schola piscatorum (the corporation of fishermen) applied to the catching of river fish, totally ignoring sea fish.11

Among vegetable products, the primary role was held by grains, with a few significant innovations since ancient times. Early in the Middle Ages, two new plants, rye and oats, came under cultivation. Previously known only as invasive grasses, they slowly took over space given to such traditional plants as spelt and wheat by virtue of their high yield and singular resistance to adversities of climate. For the same reason, “small grains”—millet, panìco, and sorghum—acquired an important role in the economy of the high Middle Ages. However, the combination of barley and oats, documented in the early years of the tenth century on the lands of the monastery of Saint Julia in Brescia,12 represents a juxtaposition of the old and the new: barley, a grain of very ancient Mediterranean tradition, and oats, a grain of recent success, known primarily in the northern regions of the European continent. To judge from local varieties, the grain lexicon of Europe in the high Middle Ages (and the alimentary lexicon in general) seems to be characterized by a common thread or, put differently, by a growing differentiation of resources so as to assure more protection in times of need.

Greater continuity, compared with the ancient alimentary tradition, can be seen in the cultivation of legumes, largely centered on broad beans, chickpeas, and beans (meaning the dolico or fagiolo dall’occhio, the only species indigenous to the Mediterranean region, all other beans having originated in the Americas), as well as a few species of lesser importance. In the high Middle Ages, the cultivation of green peas began to spread, enjoying enormous success during the centuries to follow. However, the sixth-century treatise by Antimo indicates no awareness of this, which may be significant in that one of the miracles attributed to Saint Colombano was that he made the legumen Pis spring from the rocks of the Emilian Appenines.13

There was also notable continuity in the repertory of vegetables, centered on cabbages, turnips, other root vegetables, and salad (as well as the onions, garlic, and leeks that were our starting point). We have to wait for the centuries of the full Middle Ages before coming into contact with the innovations brought by the Arabs to southern Italy and southern Spain, including such Near Eastern plants as spinach, eggplant, and artichokes.14

And, finally, with regard to fruits, we return to the theme of integration between cultivated and wild resources, typical of the high Middle Ages. The scarcity of documentation on domestic orchards15 does not authorize us to deduce the absence of these products in the alimentary system; fruits were primarily obtained from a harvest economy, uncultivated to be precise, so their modes of exploitation are hard to discern in the written documents.16

This lexicon, as mentioned earlier, has multiple territorial and social variants: even if most of the morphemes are common, they take on a different meaning according to the context. Wheat, for example, is a luxury product almost everywhere, but there are regions, as in southern Italy, where the perpetuation of the Roman economy made the wider availability of this product not only normal but also popular.17 The chestnut, which in the high Middle Ages became progressively widespread as an alternative to grains, became increasingly common in Mediterranean regions (in Italy, beginning in the Po Valley),18 although in the north it remained an exotic product.19

The use of fats and beverages is also differentiated geographically,20 but they, too, are part of that process of homologizing cultural models, that osmosis between the Roman tradition and the Germanic tradition, which, even in the domain of food, represents to my mind the most significant phenomenon in the history of the high Middle Ages in Europe. With regard to fats, the homology is articulated above all in liturgical rules that require all of Christendom, whatever the latitude, to alternate between animal and vegetable products according to the day of the week or the period of the year.21 This is why olive oil, albeit more common in Mediterranean lands, was also exported to regions of northern Europe. In the Colloquy (a text written by Aelfric, an English abbot, for the purpose of teaching Latin), in which characters from different walks of life are introduced, the merchant declares himself an importer of oil.22 Lard, on the other hand, is produced everywhere and represents one of the principal common denominators of the European model of consumption—and, let us add, the Christian model, making the pig an important mark of identity in the face of the Islamic world. The singular mode of transporting the remains of Saint Mark, filched in Egypt and hidden in a cargo of preserved pork, was not only a stratagem to foil the inspection of the Saracen guards but also a statement of cultural identity.23

As to beverages, wine had the most outstanding success by virtue of taste and prestige that went beyond its symbolism for Christians. Wine thus entered into competition with beer, which has different methods of production and different cultural traditions. Coexistence would seem impossible, given the almost perfect opposition of the two beverages in terms of use, whether nutritive or social, ceremonial or even religious. In this latter case, however, examples of their cohabitation are not lacking: “Should it happen that there is not enough wine,” we read in the rule for canons written by Chrodegang, bishop of Metz, “we can console ourselves with beer.”24 Wine has always been recognized as having a higher value, so it was normal to find imported wines in the markets of northern Europe, whereas no one in southern Europe imported or produced beer. Aelfric’s merchant imported wine as well as oil.

Beyond that, innumerable merchants from all European countries bought and sold spices, which, despite their exoticism, entered the alimentary language of the high Middle Ages in an organic way. Whereas the cuisine of ancient Rome used only pepper, during the Middle Ages spices multiplied and were differentiated as the repertory grew steadily richer.25 In the case of spices, we are confronted with a special kind of lexicon that points to an exclusive group of consumers, delimited by those with access to markets of luxury goods. This may be the principal anomaly in a lexicon—viewed as a whole and, for the most part, shared on a social level—that defines differences in a primarily quantitative sense (during the high Middle Ages, to eat a lot projected an image of prestige and power)26 and presupposes a common knowledge of alimentary resources, if not always of their uses. Within this unified culture, the qualitative differences—in particular, the absence of meat from the monastic diet27—would seem to be the result of cultural choices that, while rejecting certain common practices and values, nonetheless used the same lexicon.

If products constitute the basic alimentary lexicon, its morphology grows out of the ways in which these products are developed and adapted to the various needs of consumption: concrete gestures and procedures (modes of cooking and preparation) transform the important ingredients into words—that is, into dishes for various uses and functions. For example, with grains one can make polenta, bread, pies, and focaccia. The basic ingredients are the same; what is different is the gastronomic result, determined by the kind of procedure performed on them. It is always the gestures, the procedures (the recipes), that account for the relationship between the units of meaning. The linguistic phrase tortelli di ricotta, which uses the morpheme di (of) to designate the subordinate role of the second element in relation to the first, is expressed in culinary practice by the simple gesture of including ricotta in the tortelli. Every gesture has its meaning. The addition of a little honey, or raisins, or cooked must, or something more exotic such as dates is enough to go outside the nutritive and ordinary dimension of the dish and enter into that of delicacy, of festivity, of dulcis in fondo (which medieval taste also looks for, although unaware, at least in any rigid sense, of the distinction between sweet and salt more common in modern culture).28

Techniques of conservation also determine the morphology of products and confer a meaning. Conserved products (salami, cheese, meat, and dried fish) belong, by definition, to the alimentary “discourse” of the less advantaged, connoting the basic need to provide continuous provisions so as to avert the risk of an empty larder. The treatment of vegetables and fruits enters into this same logic, and the centrality of grains in the alimentary model of the peasantry is related to the particular preservability of these products, in addition to the many ways they can be used. On the other side, the pleasure of fresh products, whatever they may be, is a sign of social privilege and economic security—it being understood that even the larder of a well-endowed monastery, a powerful layperson, or the sovereign himself held a stock of conserved products (amply attested, for example, by the storehouses of royal courts, as we know from the chapter de villis by Charlemagne).29

The transformations resulting from culinary practices and cooking modes are filled with social and symbolic implications. A roast is typically seignorial, expressing—as Claude Lévi-Strauss has taught us30—the predilection for nature and wilderness (always ambiguous but a cultural choice31 nonetheless) that we associate with medieval aristocracy. The comment made by Eginard on the culinary preferences of Charlemagne, who every day ordered his hunters to prepare spit-roasted game, “which he ate with more pleasure than any other food,”32 not only suggests the emperor’s personal taste but also involves more complex images that refer to an awareness of self and to class identity. Eginard further informs us that Charlemagne, though suffering from gout, quarreled with his doctors “because they urged him to give up roasts, to which he was accustomed [assuetus], and to eat boiled meat instead.” That dish he found “particularly odious” and pushed it away with disgust.

Boiled dishes, in fact, primarily associated with the domestic dimension of food and with the use of cultural mediators such as pots and water for cooking, are typical of peasant food and express diametrically opposite values. On the material level, the prevalence of boiled dishes in the alimentary practices of peasant kitchens is confirmed by archeological data that provide evidence from medieval village sites of the precise correlation between the dimension of the pots and the size of the bones discovered in waste heaps.33 The symbolic implications attributed to boiled meats began out of concern first for economy and then for the greater yield from this procedure: to cook in a pot rather than directly over fire prevented the loss of the nutritious meat juices, which were preserved and concentrated in the cooking water. The broth obtained this way could be used again for other preparations, adding other meats and vegetables. Furthermore, the use of water was indispensable when cooking salted meats, also typical of peasant food.

In the systems of cooking meat, there was also a motivation, explicit or implicit, of a dietary nature related to the canon of classification determined by ancient science and passed on by medieval medicine. That science, as is well known, based its observations on the notion of four fundamental “qualities” (hot and cold, dry and moist), which, when combined in various proportions and to variable degrees, defined the nature of everything edible.34 And because the purpose of cooking, beyond those ranging from enhancing taste to promoting health, was to avoid all excess and to equilibrate the “humors” of the body (derived from the combination of the four “qualities”), boiled dishes, using water, were held to be ideal for meats of a “dry” nature as well as for those preserved with salt or from old animals (old age, according to the medical theory of the time, was presumed to contain an excess of dry and cold). The meat of young animals, being qualitatively moist, was treated instead with fire, meaning spit-roasted.

This kind of dietary culture—based not on abstract ideas but on perceptions that were instinctive for the most part—was shared by all social strata. Peasants were not ordinarily readers of dietetic texts, but their choice of boiling meat corresponded to their needs and to practices that integrated perfectly with the scientific canons. The meats they cooked, if not salted, were assuredly not from young animals. Only lords could allow themselves the luxury of regularly consuming the meat of young animals, prematurely taken from their other uses. The duality roasted/boiled therefore worked well from every point of view: the economic and symbolic values, the quest for gastronomic pleasure, and the observance of dietetic principles were rigorously maintained, each reinforcing and justifying the other in turn.

Syntax is the structure of a sentence that lends meaning to language and to its morphological variants. In the present instance, it is the meal that determines the order of dishes according to criteria of succession, accompaniment, and reciprocal relationship. As in the verbal sentence, one or more forceful nuclei (similar to the nucleus of subject/verb) stand at the center of the action. It can be a simple nucleus, as when one dish and a single course comprise the menu. Or it can be multiple nuclei (more foods, more courses) with increasing degrees of complexity depending on the ritual importance of the event and the social standing of the protagonists.

The model of the single dish, typical of the peasantry, is to be found in the meals distributed to the poor, according to available documents. Pope Adrian issued a decree, as recounted by Anastasii Bibliothecari, that one hundred indigents be fed every day in the Lateran basilica. This was accomplished by filling a huge cauldron with meat, grains, and vegetables, accompanied by bread and wine.35 Into the pulmentum (porridge, or stew, or simply a “cooked dish”) of this caldaria went pigs, wheat, and barley from a property on the outskirts of Rome: it is the exemplar of the “synthetic” organization of a meal in which all the ingredients are mixed together. Similarly, the priest Rissolfo ordered in 765 that the needy of Lucca receive a pulmentarium consisting of beans and panìco (foxtail millet), “thick and well seasoned.”36

Pulmentum or pulmentarium is a term often seen in medieval documentation, designating fairly different preparations.37 It does not indicate a specific composition; it can contain vegetables, grains, meat, or fish, according to the situation and the circumstances. Very simply, pulmentarium is the “dish,” the “food.” Generally, and precisely, it is the cooked dish as prescribed in the Benedictine Rule, two of which should be served to the monks at their daily dinner (duo pulmentarium cocta). This specification, emphasizing the monastic commitment to a communal and “domestic” life and dissociated from the solitary, wild, and “raw” model of the hermit’s diet,38 is characterized by the act of cooking—the morphology of the preparation—the action that allows the ingredients to acquire a meaning, to enter into an alimentary system that is shared by a society. But within this system, raw food also has its place: the third pulmentarium that may be offered to the monks is a dish of raw vegetables and fruits.39

Even richer and more complex models of menus are articulated around this basic structure through the elementary and extremely simple mechanism of multiplying dishes. The monastic regimen itself, proposing two or three dishes at each meal, follows this model and confirms it. One, two, or three pulmentaria40 signify a greater importance given to food as an expression, for example, of joy: on feast days, the dishes will be more numerous. This is not about reorganizing the structure in a different way but merely about replicating and multiplying it. “During major holidays courses are added to lunch and dinner,” states Cesario’s Regola per le vergini (Rule for virgins).41 And Valdeberto’s Rule ordains that “on feast days, in honor of the holy solemnity, we will restore our body with a larger number of foods, that is, three or four dishes.”42

The comprehensive nature of the expression pulmentum is defined by its components only in some cases. The statutes of the monastery of Corbie, in Picardy, specify that the pulmentarium of the monks is to be made of “greens of various kinds.”43 The first Camaldolese constitutions wanted it to consist of greens and vegetables but also of fish “and every kind of food that a monk may eat.”44 Elsewhere, outside of the monastic environment, one finds the component of meat—above all, where the territorial and cultural context assigned to meat a nutritional role of the first order. The pulmentum allotted to the canons by the Chrodegang Rule, in force in Metz during the middle of the eighth century, was organized into two separate elements: the “portion [ministracio] of meat” (one for two canons) and the more generic cibaria—with the proviso that “in case there are no other cibaria, they receive two portions of meat or lard.” During Lent, meat was replaced by portions of cheese, to which was sometimes added a third pulmentum of fish or vegetables. With this Lenten food, they could find consolation (consolacionem habeant) during years when a scarcity of acorns and beechnuts prevented the raising of enough pigs to satisfy the usual “portion of meat.”45

If pulmentum is a concrete unit, meaning the dish, its syntactic function (that is, its function in the context of dining) is expressed by the term ferculum, which indicates the act of the course rather than the contents of the dish.46 The two do not generally coincide because each course contains multiple dishes. As we have already seen,47 it was customary during the Middle Ages to serve a variety of dishes, all at the same time, among which the diners could choose. Such a system, in practice most commonly (though not exclusively) during opulent banquets, corresponded better to the culture of the time in its emphasis on the idea and the practice of sharing food. Around peasant tables as at lordly banquets, dishes were brought to the table on platters used by all the diners (or no fewer than two, as prescribed by ceremonial courtly rules of the early Middle Ages48).

This manner of serving food could give rise to embarrassing situations, as when a neighboring diner emptied the platter (or tagliere [cutting board] as it was sometimes called), taking advantage of his ability to swallow food that was still exceedingly hot. It was precisely for this reason that no one wanted to sit beside Noddo d’Andrea—the protagonist of an entertaining sixth-century novella by Franco Sacchetti49—who could gulp down “boiling maccheroni.” Tragicomic instead is the account of the dinner—a genuine piece of theatre, written by Gregory of Tours in the sixth century50—that a married couple, she Catholic, he Arian,* decides to offer the priests of the two religions who are competing to be primate of the village. When the meal is ready, the host proposes to “his” priest that they play a joke on the “Roman” priest. He asks for the priest, as soon as the dishes are brought in, to “hurry and bless them with your sign so that he will not dare touch them and we, thanks to his sadness, will be cheered by eating.” They agree. The first to arrive is a dish of greens. The “heretic” (so defined by the author) priest makes the sign ahead of the other priest. The wife, so as not to offend him, brings in another dish and offers it to the Catholic. But the heretic continues his blessings on the second and the third course (in secundo et tertio ferculo). At the fourth course, the drama begins. In the center of the platter is a handsome display of eggs scrambled with flour, decorated with dates and olives. Before the platter is even set down on the table, the “heretic” hastily raises his hand to bless the dish, immediately extends his spoon, takes up the food, and quickly gulps it down. Sadly for him, he is unaware that it is still burning hot. His chest flares up with intolerable pain, his belly erupts in a dreadful roar, and his breathing stops. The frittata has killed him. Unperturbed, the three survivors carry him out of the dining room, bury him, and go back to eating. Now that God has vindicated his servants, the “good” priest says to the master of the house, “Bring me something that I can eat.”

In their relation to the principal subjects (the dishes) within the syntactical structure of the meal, the “complements” become defined in time as those things that precede, accompany, and follow: appetizers, intermediate dishes, side dishes, and “dessert” (as it is called today). Sauces can be seen as analogous to grammatical morphemes such as conjunctions or prepositions, bereft of autonomous meaning but essential for determining the nature and quality of the protagonists. Here, we must return to the relationship between alimentary practices and dietary science because sauces (almost inevitable in medieval cooking, as demonstrated by the space devoted to them in contemporary cookbooks) were selected and paired on the basis of the “humoral temperaments” borrowed from the medical tradition. For example, a meat that is cold and dry by nature—as determined by the characteristics of the animal but also by the way it is cooked—has to be accompanied by a sauce made of opposing products. From a rhetorical point of view, we could say that the prevalent figure of speech in medieval cooking is the oxymoron.

Condiments fall into the function of grammatical adjectives or adverbs. Their choice can be tied to reasons of economy (the availability of resources) or ritual (in Christian Europe the liturgical calendar with its “lean” [meatless] and “fat” requirements) that confer on foods a spatial/temporal connotation typical of adverbs. The alternation lard/oil, with the possible local variant of butter, signifies identity with a territory, a society, or a culture as well as with the day, the week, or the period of the year. The eighth-century document from Lucca, mentioned earlier, ordains that the dish intended for indigents should be dressed with “lard or oil” depending on circumstances.51

Bread plays a decisive role in this alimentary system, in a way both parallel and autonomous. Bread is the perfect “complement”; according to Isidore of Seville, “it goes with every food.”52 To turn this around, bread is the food that is accompanied by all other foods. This introduces into the alimentary discourse a kind of dualism: pane e companatico (bread and, literally, what goes with bread)—or, in the more typical terminology of the high Middle Ages, panes vel pulmenta53—means two entities that complement each other and are alternately integrated in inverse proportion. In some cases, the nucleus is bread: in the Benedictine Rule, bread is mentioned after and separately from pulmentaria, but the determined portion (a pound per day to each, every day of the year without distinction)54 seems to guarantee on this nutritional scale the necessary minimum, integrated with other foods. When, instead, the nucleus is pulmenta (as in the diet of the Chrodegango canons of Metz), the attention is focused on meat, and the concern is to find “consolation” for the scarcities by turning to other cibaria such as cheese, fish, or vegetables. Bread, in this case, is limited to assuring that the canons eat quod sufficiat (as much as needed).55 The contrast between the two models, at the same time territorial (southern and northern Europe) and cultural (monastic regimen, observing abstention from meat; canonical regimen, closer to the secular model), takes on social equivalence when compared with the aristocratic table, on which meat always holds a dominant place. In this case as well, bread quod sufficiat is never lacking, but it serves a supplementary function.

The case of bread can serve to illustrate the highly structured nature of the alimentary system and, within this system, the fact that everything has its place, the primary objective being to hold on to it. What comes to mind are the strategies used in the event of penury or scarcity, when the basic lexicon, the customary “repertory of products,” is unexpectedly reduced. These strategies seem to reveal a general rule: despite the forced abandonment of usual practices, one must remain as close as possible to one’s own culture, to the language one knows. The prevailing attitude is one of substituting, of locating something that can be used in place of something else. Medieval chronicles (and also those of later centuries) document all kinds of inventions for the purpose of adapting available products to familiar techniques and practices. If wheat was scarce, bread was made with inferior grains—a common practice among the lower classes even in normal times. Other times legumes were utilized (especially broad beans) or, in mountainous regions, chestnuts (not by chance is it called “tree bread”) or acorns. Later it might have been roots and wild herbs. “That year,” Gregory of Tours wrote, referring to events at the end of the sixth century, “Gaul was stricken with a terrible famine. Many people made bread out of grape seeds, or with the flowers of hazelnut trees, others used the roots of pressed ferns that were dried and reduced to a powder mixed with a bit of flour. Still others did the same thing with field greens.”56 In extreme cases, people had recourse to earth. In 843, according to the Annals of Saint Bertin, “in many places people were forced to eat earth mixed with a little flour shaped into the form of a loaf.” Notice the expression of the chronicler: earth “shaped into the form of bread [in panis speciem].” The form, the morphology of the food, is what guarantees the continuity of the system.

“Bread of famine” recurs often in the sources. In 1032–33, Raoul Glaber related in a famous passage that “an experiment was attempted that has not been found to have been made ever before. Many people collected a white sand, similar to clay and, combining it with whatever flour and bran were available, produced a kind of roll in the hope of thereby alleviating hunger.”57 Unfortunately, they met with no success but did meet with painful consequences as regards digestion. This was nonetheless, as Pierre Bonnassie has rightly noted, the most “rational” response to famine58 before falling into other kinds of behavior induced by panic and madness. Not only the consumption of certain products but also the renunciation of habitual practices of preparing and cooking food was seen as the abdication of one’s identity, an indication of the descent into animalism: to eat grass “like beasts,” without dressing it or cooking it—that was the decisive step. On the other hand, stealing acorns from pigs, grinding them with other chance ingredients, and trying to turn this into bread (as Geoffredo Malaterra informs us, referring to the dramatic famine of 1058 in southern Italy59) comprise a cultural gesture, born of an extremely refined and complex culture that, moreover, gave rise to survival techniques developed and transmitted by generations of starving people: “As is habitual among the poor [sicut pauperibus mos est], they mixed herbs with a bit of flour,” records a chronicle about the 1099 famine in Swabia.60

What is striking about these dramatic events is the persistence of a direct reference to common alimentary practices. To recall the parallel between the alimentary system and language, this would be like modifying something in the lexicon without touching the morphological and syntactic structure of the discourse.

In only a few cases has there been a need for changes (generally temporary) by the substitution not of products, of ingredients that enter into the making of a given dish, but rather of the type of dish. For example, it might be necessary to replace dishes based on grain (soups, polenta, even bread) with meat or other animal products, which was possible only when the range of available resources was sufficiently broad. And this was the case during the high Middle Ages, when the models of consumption, based on an economy tied for the most part to the exploitation of forests and natural herding rather than agricultural practices, were fairly flexible, so that it was often possible to replace foods by turning to different sectors of production.61

The scarcity of bread has always caused serious alimentary problems, but in many cases, the agricultural crisis could be met with resources provided from the noncultivated economy.62 The so-called Rule of the Father, composed in northern Europe, provided for a supplement of milk in the event that sterile lands made the supply of bread inadequate.63 The Life of Saint Benedict of Aniane recounts that in 779 a multitude of starving people rushed to the gates of the monastery asking for bread; in the absence of anything else, they were fed every day “the meat of sheep and cows, and ewe’s milk”64 until the new harvest. More dramatic is the information given by Malaterra that during the famine of 1058, mentioned above, the consumption of “fresh meat without bread” was the cause of dysentery and death. This report may be less of a hygienic explanation than the reflection of a culture, such as the Mediterranean, viscerally associated with the idea of bread as crucial, even symbolically, to the alimentary system (not to mention the ulterior moral connotation because it was the season of Lent and meat should not have been eaten).

Reports of this kind seem to me typical of the high Middle Ages. The same consumption of meat during Lent, documented in various sources as a choice in cases of emergency,65 seems related to an alimentary, economic, and cultural system in which a forest economy held great importance. Over time, the peasant diet became more uniform and monotonous, based more and more exclusively on grains. Starting in the Carolingian period, the extent of forested areas began to shrink and, most important, to be transformed into reserves for the pleasure of the powerful, accompanied by the double pressures of a growing population and the demands of the lords for larger agrarian yields.66 From then on, meat increasingly became a mark of social privilege. If until then grains and meat were the equal subjects of a single alimentary discourse—differentiated on a social level but for the most part only quantitatively—from then on, there were two different discourses, one centered on meat and the other on grains.

The language of food, whose grammatical structure we have been examining, could not be fully expressive without the rhetoric that is the necessary complement of every language. Rhetoric means adapting the discourse to the argument, to the effects one wishes to produce. If the discourse is food, rhetoric is the way in which it is prepared, served, and consumed. To eat like “a famished lion who devours his prey”—as does Adelchi (the son of the defeated king of the Longobards) after intruding into the dining hall of Charlemagne to make known his presence and his avenging challenge67—signifies that voracity expresses strength, courage, and the sense of animal vigor that the aristocratic society of the high Middle Ages perceived as the fundamental value of its own identity. The huge pile of bones that Adelchi leaves under the table is a way of communicating all this; his adversary Charlemagne speaks the same language and understands it perfectly.68 The monastic ritual of silence, requiring the monks to listen to sacred readings without speaking during meals, goes in an entirely different direction, expressing in the manner of consumption, beyond what is consumed, a control and a discipline of oneself imposed by the rule and the lifestyle chosen. About peasants we know little, but it takes no effort to imagine that they were as voracious as Adelchi, not for the purpose of adhering to aristocratic models of animal strength but to assuage their hunger.

What we see are collective gestures, a conviviality† that can represent the interests in force at the time precisely because of a common language and the practice of sharing a meal that seems innate in humans, being the social animals that they are (“we do not invite one another so as to eat and drink,” wrote Plutarch, “but to eat and drink together”69). This is the little secret that explains the extraordinary communicative efficacy of alimentation and its inherent ability to structure itself as a linguistic system. Every gesture made in the presence of others, along with others, acquires for that very reason a communicable meaning.

Here, as elsewhere, economic reasons bind with images and symbols. This may be what is most fascinating about the history of alimentation: to recognize the profound unity of body and mind, matter and spirit; to bridge the separation between levels of experience, that fictitious dualism that has for so long marked our culture. Historical analysis cannot account for this, and ideological interpretation is even less able to do so. Food in human societies takes on all kinds of values, but these do not supersede (nor can they supersede) concrete uses and modes of production, transformation, and consumption. The language of food is not discretional; rather, it is conditioned and, in some way, predetermined by the concrete, economic, and nutritional qualities of the lexicon utilized.

In the end, an onion is an onion.