IN THE LANGUAGE of Homer, “bread-eaters” (sitòfagoi) is synonymous with “men.” Eating this food is essential and sufficient to being man—not men in general but the men of Homer: the Greeks, the bearers of civilization. Those who do not eat bread are for that very reason “barbarians.”1

In point of fact, bread cannot be regarded as the “original” food of humanity. The ability to make it presupposes a series of complex techniques, not at all self-evident (growing grain, grinding it, turning it into dough, making it rise, baking it, and the like), that represent the fulfillment of a long history, a refined civilization. It was this that Homer had in mind, as did those who, along with him, were born and raised in the world that we are given to calling “classical,” defined geographically by the shores of the Mediterranean. Even in the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh, the most ancient literary text known, the civilizing process of Enkidu, who lives as a “wild man” among the beasts of the forest, is accomplished when he learns to eat bread.2

From the time that agriculture was invented in the Stone Age, Mediterranean people based their alimentation largely on grains. People from others parts of the world did the same, given that grains provide incomparable advantages for survival. They are extremely adaptable with regard to gastronomy; they keep well and without much effort throughout the year. This is why in various parts of the world these “civilizing plants”—as Braudel felicitously termed them—took hold and became the center around which the whole human experience revolved: economy, society, politics, and culture.3 Every aspect of civilized life was tied to grains, directly or indirectly. Intense efforts were directed toward producing these plants; control of their production (and the resulting commerce) defined the wealth or poverty of individuals; huge efforts on the part of public officials (the king or his delegates) were made to assure regular provisions to the people, to maintain order and stability (the very legitimacy of those officials depended on knowing how to solve the problem of daily hunger);4 and, finally, it is around these products that cultural values, myths and legends, religious symbols, and every other form of intellectual creation evolved. This is what allows us to talk about “civilizing plants”: for the populations of East Asia, rice; for the inhabitants of Central and South America, corn; for Africans, sorghum and later manioc; and for Mediterraneans, wheat. From wheat was created bread—a food to be mastered, invented day after day, and thereby handed down as a precious technological heritage.

The Romans, according to Pliny the Elder, did not have public ovens for baking bread before the second century B.C..5 Earlier, they ate mostly soups, porridges, and flat bread. They then learned the art of leavening and bread making, which the Egyptians had apparently been the first to perfect, spreading it among the people of the eastern Mediterranean. The Hebrews certainly were familiar with it, although nevertheless maintaining an ambiguous attitude toward it. On the one hand, it was a fundamental resource of daily food. On the other, it was included among the products that did not enjoy elevated, sacred ideological stature,6 insofar as it was a fermented food, making it “corrupted” compared with the original purity of the raw material. Christianity, instead, made bread—along with wine, another fermented product—sacred food, the instrument of eucharistic communion with the divine. It was a choice that knowingly signified the break with Hebraic tradition. Not by chance, one of the reasons for the conflict between the Roman and Greek churches, officially separated in the eleventh century, was the accusation made by the Orthodox against the Catholics that, with the introduction of the unleavened communion wafer, they had abandoned the “true” Christian tradition of fermented bread and gone back to the ancient Hebraic model.

The symbolic importance that Christian writers of the fourth and fifth centuries attribute to bread is remarkably intense. A sermon by Saint Augustine dwells with great precision on details of the metaphoric similarity between the making of bread and the making of a Christian:

This bread tells our story. It arose as grain in the fields. The earth made it grow, the rain nourished it, and made it mature into a kernel. The handiwork of man brought it to the threshing floor, beat it, aired it, stored it in the granary, and brought it to the mill. He ground it, turned it into dough, and baked it in an oven. Remember that this is your story as well. You did not exist and were created,* you were brought to the threshing floor of the Lord, you were threshed by the work of the oxen, meaning the Evangelists. While waiting to become catechumens you were like grain stored in the granary. Then you lined up for baptism. You underwent the grindstone of fasting and exorcism. You came to the baptismal font. You were kneaded and turned into a unified dough. You were baked in the oven of the Holy Ghost and truly became the bread of God.7

But the ideal bread is Christ himself, “inseminated in the Virgin, fermented into flesh, kneaded in suffering, baked in the oven of the sepulcher, seasoned in the churches that every day distribute the heavenly food to believers,” as we read in a sermon by Pietro Crisologo.8

The rise of bread as a sacred food undoubtedly aided the integration of the Christian faith into the value system of the Roman world. Or perhaps we should invert the argument and recognize in the ritual exaltation of that product the sign of a culture—the Roman, to be precise—that itself borrowed many aspects of nascent Christianity. Whether due to the prestige of Roman tradition or the galvanism of the new faith, the image of bread underwent an extraordinary elevation during the Middle Ages. Parallel to the affirmation of the Christian religion, bread became the preeminent food, not only for Mediterraneans but for all of Europe. Even those who were once called “barbarians,” more closely tied to pastoral than agricultural traditions and to a primarily carnivorous alimentary model, yielded to the appeal of the new alimentary model and contributed decisively to the propagation of the “culture of bread” throughout the continent.

And there is more to this. Beginning when Islam gained a hold on the southern shores of the Mediterranean, between the seventh and eighth centuries, that sea turned into a huge common lake, as it had been in Roman times, a sea of borders.9 Here, two different worlds—two different civilizations, religions, and cultures—came face to face and perhaps even met, although from opposite shores. The world of the civilization of bread was obviously on the northern shore, or so it saw itself. There was great ideological tension among Christian writers who, during the period of the Crusades, regarded bread as the mark of their own identity and described Arab bread as “poorly cooked flat breads” that hardly deserve the name of bread. There is something more substantial here than gastronomic primacy. Bread by then had become an instrument of cultural conflict. And for that very reason, at the price of obvious force, bread became the symbol of Christian Europe. No force, however, was involved in the “Christianization” of wine, which, once banned from Muslim territories, was transformed from a Mediterranean beverage into the beverage of the European continent. It was like a comprehensive displacement to the north, the “continentalizing” of the Mediterranean alimentary model, corresponding to analogous political and institutional events. The bishops and abbots, described in hagiographic sources as intent on planting vineyards and using woodlands for agriculture, were in the forefront of the progressive change in alimentary habits.10 The new “Roman empire” of the Middle Ages, that of Charlemagne, no longer had the Mediterranean as its axis; it had all of Europe.

In the north-central regions of the continent, the culture of bread took on new forms. Inserting itself into alimentary structures that had meat at their center rather than grains, bread changed its position from a basic food to an auxiliary food, though no less enjoyed and perfected. Quite the opposite, and not paradoxically, it was even more exalted in its specific gastronomic functions by being less basic. In northern Europe during the high Middle Ages, bread was considered a precious food, a rare food, and a fashionable food.

With time, bread became a common food and acquired central importance in the daily diet, not only for cultural reasons but also because of the modification of the economic and demographic situation. During the high Middle Ages, a largely woodland/pastoral economy guaranteed on every table the presence of meat, in perhaps small but nonetheless regular and continuous quantities. In those centuries, bread was not as irreplaceable in strategies for survival as it would become in the centuries after the year 1000. The growth of the population, the resulting expansion of agriculture, and the transformation of so many woods into private hunting grounds, taking them out of collective use, excluded the majority of the population from resources of meat, forcing it to depend almost exclusively on grains.11

From then on, the consumption of bread acquired a different social and cultural connotation. It began to characterize and to define the diet of the poor, to which peasants and lower classes in general were constrained. For all these people, the consumption of bread remained very high and decisive over centuries. In European countries, daily rations of bread from 700–800 grams up to a kilo and more have been documented as normal in the Middle Ages and beyond, at least up to the nineteenth century. Bread provided the most consistent portion of the daily caloric intake: 50 to 70 percent, according to calculations.12 The expression companatico, which appeared in the Middle Ages to indicate everything that “accompanies” bread,13 is the most convincing linguistic proof of an alimentation by then solidly based on that product.

In peasant houses, bread was eaten—God willing—every day. “As was the custom of rustics [sicut mos rusticorum habet],” a farmer, Gregory of Tours tells us, received bread from his wife, which he did not begin eating before having it blessed by a priest.14 Let us not think that bread was freshly baked every day; obvious economic reasons demanded other choices. Until recent times, the large loaves of the peasant table were made to last for the better part of the week. Antimus, a sixth-century doctor, was therefore not referring to the majority in his treatise on diet when he recommended to the king of the Franks that bread, “well fermented and not unleavened,” be baked every day, if logistically possible, because “such breads are more digestible.”15 This happened only in well-to-do houses or in monasteries. At Corbie, in northern France, the Statutes of Adalado direct that the 450 loaves necessary for the sustenance of the monks, their dependents, and their guests be baked daily. However, the “custodian of bread” (an office planned by the Benedictine Rule) had, in reality, to make certain that the quantity of loaves that came out of the ovens was commensurate with the number of persons actually present, so that if any loaves were left over, they would not be found later to “have become too hard.” In such an event, “that bread will be put aside and another will be served in its place.”16

Even aristocrats ate bread. At princely banquets, along with the many meats, bread was served de rigueur in “gilded baskets”—as Cherubino Ghirardacci mentions in his account of the elegant banquet held in Bologna in 1487 to celebrate the marriage of Annibale Bentivoglio to Lucrezia d’Este.17 Except that this was a different kind of bread, which could be seen at first glance because of the color: the bread of the wealthy was white, made entirely of wheat; the bread of the poor was dark, made in whole or in part of inferior grains—rye, oats, spelt, millet, and foxtail millet—products that for centuries scanned the rhythm of peasant alimentation. In the cities, even the poor ate white bread so long as there was no shortage, but, in fact, bread became unavailable or scarce with despairing regularity. The great success that the scriptural “miracle of the seven loaves”18 encountered in Christian Europe, where it was persistently referred to by a mass of aspiring saints, is also a sign of a demand too often thwarted and disregarded.

This same prevalence of inferior grains in the diet of the lower classes often made it impossible to produce bread: certain grains such as barley and oats are hard to make rise and are better adapted to boiling for soup or porridges (using farina) or simply to making it into a flat bread (such as focaccia or pita), to which we often see attributed, almost abusively, the name of “bread.” A wishful bread, we might call it, just as the “breads of famine” are utopian and pathetic, the result of centuries of technical knowledge, handed down from generation to generation, on how to make bread in times of hardship when not only wheat but also other grains were lacking. That is when legumes and chestnuts came on the scene, or perhaps acorns, grasses, and roots were mixed in with a minute amount of flour—and on occasion a bit of earth.19 Even cultivated men took pains to explain to the peasants—in texts on agronomy20 or later in specific treatises—what they probably knew only too well: how to make bread out of field greens and wild plants.21

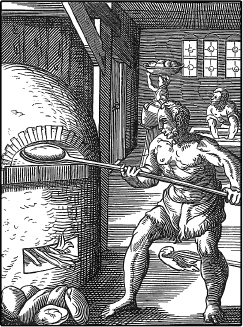

The use of fire required considerable experience and ability; it was hard to keep a steady temperature when baking loaves that were placed in different parts of the oven. Overbaking must have been a not infrequent occurrence if monks were authorized by the Rule to scrape up the burned crusts of bread; in the cities, there were special places for the sale of over- or underbaked bread.

During the Middle Ages, it was still common to find small ovens like those used in antiquity (and even today, by various peoples) in which the raw loaves were placed directly on the heated walls, to be detached once baked. This procedure, executed on overturned clay pots placed directly on the hearth, was better suited to unleavened dough, which would adhere better to the walls. Obtained this way was a bread called clibanicus,22 similar to pancakes and flat breads that were cooked on a slab. With little yeast or completely unleavened was the bread cooked in embers: “the bread that is cooked by turning it in ashes,” wrote Rabano Mauro in the ninth century, “is a focaccia.”23

Bread made of wheat represented a luxury product throughout the Middle Ages, and it was precisely to reject this luxury that hermits chose to deprive themselves of it, replacing it with a barley bread having a clear penitential intent. This bread was little appreciated because of its sour taste and was considered barely digestible because of its reduced gluten, which did not allow for complete rising. If Roman soldiers could be given this as a punishment for having abandoned their posts,24 no hermit would then deprive himself of it as a means of mortifying the body and the desires of the flesh, as did a philosopher in antiquity.25 The complexity of such situations, including their symbolism, is witnessed by behavior such as that of Gregory, bishop of Langres, who did penance by eating barley bread. Because he did not wish to appear pretentious, he ate it secretly, holding it under the bread made of wheat that he offered to the others and pretended to eat with them.26 Similarly, Radegonda “ate bread made of rye and barley in secret,” so that no one would notice.27 This penitential significance occasionally crossed the confines of the monastic or eremitic society. Gregory of Tours, in his History of the Franks, recalls that during the plague that hit Marseille in the sixth century, the king invited the people to do penance by nourishing themselves exclusively with barley bread, so as to obtain from God the end of that calamity.28

What is clear is that the criteria for the appraisal of bread varied from region to region: for example, whereas rye bread was considered vilissima (disgusting) in a French geographic and cultural environment,29 in a German context it was seen as pulchrum (beautiful).30 In the monastery at Corbie, in northern France, spelt bread was apparently much appreciated for it was distributed daily to everyone—monks, servants, vassals, and guests.31 There are also cases of outstanding opulence, when precious wheat was used for every sort of preparation, even for polenta: “five bushels of the purest wheat [ad polentam faciendam]” were to be sent to the Parisian monastery of St. Denis under a decree from the emperor Charles the Bald in the ninth century.32

Widely used was a long-lasting bread that had been dried in the sun and subjected to double cooking (bis coctus). Roman soldiers33 ate similar loaves, called buccellae; in the Middle Ages, for various reasons, it was mostly hermits and pilgrims who ate them. Hermits could assure their food supply with this twice-cooked bread, thereby freeing themselves from contact with society and the “world” from which they had fled.34 Legend had it that certain hermits of the Thebaid had bread that lasted as long as six months. Pilgrims also needed an adequate food supply for the long journeys they undertook.35 This bread was dry and had to be soaked in water (infundee) to make it edible.36 At times, it was used as the basis for soups, being crushed and mixed with water, wine, or other liquids. Stale bread could be softened by a second cooking in water, with the eventual addition of other condiments. The raw dough itself was sometimes cooked in water to obtain a softer bread than the usual one, and the same result was achieved by the addition of milk or, in northern countries, the foam of beer.37

The high respect for bread went as far as the crumbs. In the sixth century, the Regula Magistri (Rule of the Master) ordained that the micae panis remaining on the table after each meal were to be collected very carefully and kept in a container. Each Saturday the monks were to put them in a pan with some eggs and flour and make a little pancake that they were to eat together, thanking God before the last hot drink that ended the day.38 In less ritualized forms, but with the same concern not to waste any usable resource for daily survival, we can be sure that something of this kind took place in peasant houses as well.