IN THE EUROPEAN gastronomic system, fish long held a highly ambiguous position—or “status,” as Flandrin would have called it.1

What does this mean? It means that the experiences of our life are not merely what “is done” (or in this case, speaking of food, what “is eaten”); things have their own significance, a “meaning” within the system of values developed by each society. Foods, in short, have a value—and related to it a potential for communication. If I say “sardine,” for example, I do not think only of a fish but also of a situation (in this specific case, food of the poor, a simple meal with simple people, certainly not an opulent banquet). If instead I say “sturgeon,” I think, once again, not only of a fish but also of a costly delicacy that does not appear on the table of the poor or on the everyday table. The idea that comes to me in this case is one of wealth or festivity because sturgeon is expensive and is not often eaten. In this connotation, all our foods are weighted with expression, even emotion. And their “value” is not necessarily related to how good they are or whether I like them. Caviar might even be distasteful to me, but there is no question that it evokes an image of refined conviviality and sumptuous wealth. The “values” in question have a social dimension; they are collective images that cluster around foods. And that is their “status”—a status that changes with time and space, according to fashions and customs. The same food can be prized in one place and disdained in another; it can mean one thing in one period and something else in another.

The ambiguous status of fish in medieval culture (an ambiguity, moreover, that has lasted until today) is related to the fact that in the European tradition this kind of food has been accorded numerous statuses, almost all of them extreme. Fish is a mark of poverty, as well as prosperity; it is the humble bluefish that fishermen grill over a wood fire but also the costly whitefish that one eats at a seaside restaurant on a Sunday. What is generally missing is the normal dimension. Fish is not an ordinary food; it is not a “neutral” food. Why this contrast? Is it because the status of fish has so radically changed today in comparison with that of the past? There is no doubt that today fish is very much in fashion. And that is because it corresponds to contemporary dietary tendencies, to medical advice, and to the wishes of many consumers who prefer light foods that are easily digested. This is not as simple as it seems. On the contrary, fish reflects an inverse tendency with regard to a more than millenary cultural tradition. Fish has always been eaten, out of need or choice, but on the whole, the collective imagination has always regarded it with diffidence.

To understand the reasons for such diffidence, we must clarify an essential factor: for centuries, fish has been associated in Italian culture, and more generally in the culture of Europe, with the notion of sacrifice and penance. The Church, ever since the beginning of the Middle Ages, introduced the obligation to abstain from meat for a certain number of days during the week and the year.2 Meat in that society was seen as the aliment of the highest value. The ruling classes consumed mostly game, which they procured by hunting; the peasantry raised many animals in woods and natural pastures, thereby integrating produce from the fields. Everybody ate other things as well, but the consumption of meat held first place in their desires.3 Doctors considered it the most nutritive food, the one most capable of giving the organism strength and vigor, and this was most important in a world that attributed to food the primary function of “fattening”—that is, making one physically robust. In a period when there were no cars and no central heating, the calories expended were enormous, whether by the nobility who went hunting or made war or by the peasants who labored in the fields. For this, meat was the most important food in the daily diet. To give up meat, as the Church required, was a considerable sacrifice, a practice of humility that placed the needs of the spirit above those of the body, denying the body “its” specific nutrient for the purpose of loosening ties with the physical world.

This kind of alimentary sacrifice had important precedents in the Hebraic tradition and was also practiced by certain pagan philosophers.4 Christianity spread it on a broader scale, turning it into a true mass phenomenon. In the fourth and fifth centuries, abstinence from meat was promoted as the model by hermits and monks, either as a personal choice or in observance of a monastic rule. Later the “model” spread to the whole of society through the prescriptions of ecclesiastic authorities, who imposed abstinence on all Christians on certain days of the week (Wednesday, Friday, and occasionally Saturday) and during certain periods of the year: the eve of important holidays; the Quattro Tempora, which marked the four seasons of the liturgical calendar, and evidently Lent, the forty days before Easter. All told, liturgical rules imposed the abstention from meat for more than one-third of the year, from 140 to 160 days.

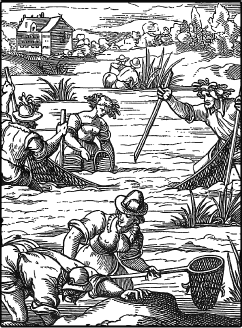

It was therefore necessary to find alternative foods for those days and periods of the year. This explains the extraordinary success (both economic and cultural) during the Middle Ages of foods seen as substitutes for meat, such as vegetables, cheese, eggs, and fish. This last, in particular, was promoted to the rank of supreme substitute for meat, becoming the alimentary “sign” of the days and periods of “lean.” It goes without saying that this development was not a straight line and did not go uncontested. In the first centuries of Christianity, there was a certain tendency to exclude fish as well from the Lenten diet because it is an animal product; this was followed by an attitude of tacit tolerance that did not prohibit it but did not prescribe it; and, finally, as of the ninth and tenth centuries, there was no question about the legitimacy of eating fish on days of abstinence.5 Only “fat” fish were excluded from the Lenten diet, meaning large marine animals (whales, porpoises, and the like that are not really fish) whose flesh looks too much like that of terrestrial animals, perhaps because of the quantity of blood. Apart from such exceptions, fish (and whatever is born and lives in water) acquired as of then, and in an increasingly clear and unequivocal way, the cultural physiognomy of a “lean” food. It became symbolic of the monastic diet and of Lenten renunciation, and its difference from meat—initially vague, if not outrightly denied—became more and more established.6

The spread of Christianity thus played a notable role, perhaps a decisive one, in placing a “culture of fish” on a par with that of meat. The Venerable Bede observed that pagan Anglo-Saxons did not practice fishing, “even though their sea and rivers abound in fish.” Among the first initiatives of Bishop Wilfred, who came to convert them, was to teach them “how to obtain food from fishing.”7 In other texts as well, one reads that the conversion to Christianity found its symbolic image in the acceptance of the Lenten diet. At the time of Charlemagne, Saxons who refused to abstain from meat during the periods imposed by the Church were punished with death.8

It took a few centuries before progress in methods of preservation could make fish a truly “common” food. Then the ambiguity mentioned earlier reappeared. If, on the one hand, fish became a symbol of humility, renunciation, and mortification, on the other, it remained a product not easily found and, above all, not easily transported or preserved in an era obviously lacking refrigeration. For this reason, fish came to be seen in the Middle Ages as a luxury product—which was something of a paradox, as the vast presence of water made fishing easily accessible (with unrestricted rivers, swamps, and lakes providing mostly freshwater fish).9 Meat nonetheless remained a more “common” food, and for this reason, in contemporary documents, aside from praise for the monastic diet exempt from meat, we find attacks against the luxurious menus of monasteries and the delicacy of the fish eaten. In the twelfth century, for example, Peter Abelard warned his beloved Heloise against giving up meat to avoid having to rely on choice fish, which was rarer and more costly: fish, he wrote, is a delicacy for discerning palates and deep pockets—too expensive for poor people.10

During the Middle Ages, freshwater fish received uncommon attention in fishing and consumption. It became, so to speak, a “terrestrial” resource. This can be seen in every kind of document, from archival acts to literary sources, from dietary treatises to cookbooks. Praise of pike is sung in a poem by Sidonio Appolinare in the fifth century; Gregory of Tours, in the sixth, honors the trout of Geneva’s Lake Léman. The epistle De observantia ciborum by Antimo, the Greek doctor who lived in Ravenna at the court of Theodoric, king of the Goths, begins his chapter on fish with a discussion of trout and perch and devotes most of his attention to pike and eel, mentioning only one saltwater fish, sole.11 Trout and eel from Lake Garda, near Mantua, are listed in the ninth-century inventories of the monastery of Bobbio; particularly appreciated were sturgeon from the Po River, famous for their size. If the bishop of Ravenna could request that the fishermen of the Padoreno (a tributary of the Po that flowed near the city before emptying into the sea) bring him, before anyone else, sturgeon longer than six feet, it was because of the particular prestige of that fish. Throughout the Middle Ages, sturgeon indicated the table of the rich; in England, it was primarily reserved for the king’s table. Preference for freshwater fish continued during the following centuries. The catalog made by Bonvesin de la Riva in the thirteenth century of the products that came to the market of Milan includes trout, dentex, carp, eel, lamprey, and river shrimp, this last heavily consumed in medieval cities. The statutes of Bologna, whenever there were problems concerning the sale of fish, never fail to add “and shrimp.”

Saltwater fish had obviously not disappeared, but it is hard to estimate its volume during the high Middle Ages in the absence of specific documentation. Later, at the beginning of the fourteenth century, the Liber de coquina—the first cookbook to have survived from the Italian Middle Ages12—indicates a degree of interest in marine resources: not only the trout and lamprey already mentioned but also bream, anchovies, sardines, mullet, octopus, cuttlefish, shrimp, and lobster are the basis of various recipes.13 Is this a rediscovery or a specifically Mediterranean phenomenon? The second hypothesis seems more likely because a few decades later a Tuscan translation of this cookbook eliminated recipes for saltwater fish and replaced them with recipes for fish from rivers or lakes.14 This would suggest a diversity of alimentary usage between the Italian “continent” and the Mediterranean coast.

The central problem, and doubtless the greatest, was that of transportation, given the high perishability of fish. The good fortune of those who liked eel was that, according to medieval authorities, it could live for as long as six days without water, “particularly,” Albertus Magnus advised, “if it is laid on grass in a cool, shaded place, and not prevented from moving.”15 It was mostly freshwater fish that ended up in the kitchen and on the table, being easier to catch and faster to transport. During a trip in Campania, Thomas Aquinas managed to eat fresh herring, which he liked, but only by miracle: a basket of sardines was brought to him, the story goes, that miraculously turned into herring. Fresh saltwater fish were indeed a rarity; only preserved fish reached the market. The practice of salting it (or drying it or smoking it or keeping it in oil) was ancient and allowed the mass of the population to observe as they could the obligation of abstaining from meat. At the beginning of the twelfth century, the perfection of preservation techniques, encouraged by the growing demand, in turn increased the demand for preserved fish, but fresh fish maintained its status as a luxury product.

It was precisely in the twelfth century that the large-scale commercialization of Baltic herring started. The following century Thomas de Cantimpré remarked that, kept this way, it lasted “longer than all other fish.” Around the middle of the fourteenth century, the Dutchman Wilelm Beukelszoon devised a system for rapidly cleaning herring from the inside, placing them in salt, and stowing them in the same boat from which they had been fished.16 This was how the fortune of the Hanseatic League (the association of German merchants in the Baltic) was built and, later, that of Dutch and Zeeland fishermen. But between the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, herring fled the Baltic (it was a phenomenon of colossal proportions, the total migration of a species), so that Dutch and Zeeland merchant ships were forced to run after them off the shores of England and Scotland.

Even freshwater fish were processed this way. From the thirteenth century, documents from the lower Danube record large fish farms for the production of salted or dried carp, a species that appears to have been introduced by monks from southern Germany along with Christianity (here again, and not by chance, we find the Christianity-fish relationship). In time, carp became one of the principal items in the economy of the country. A few centuries later Venetian ambassador Giovanni Michiel remarked that Bohemia “has fish farms so filled with fish that they account in large part for the wealth of the realm.”17 In mountainous regions, carp farming gave way to that of pike and trout. Elsewhere salmon, lamprey, and sturgeon were fished, dried, and salted, a commerce largely conducted by Venetian and Genoese merchants.18

From the end of the fifteenth century, the commerce and consumption of fish saw the entry of a new competitor that slowly overtook herring, sturgeon, and other species: cod, fished for centuries in ocean waters but now discovered in inexhaustible supply off Newfoundland. An out-and-out war for the exploitation of those waters ensued, with the Basques, French, Dutch, and English battling in engagements decided by cannons. In the end, only the most powerful navies, those of England and France, retained access to those banks.19 Dried and salted cod, known as stockfish and baccalà—the first sold by weight and the second by the piece—became a standard presence on the tables of the working classes, particularly in the cities.

Even then, the consumption of fish remained stigmatized by an ensemble of images that prevented it from acquiring unequivocally positive status and truly popular appeal. Preserved fish evoked poverty and lower-class social position. Fresh fish evoked images of wealth but a hardly enviable wealth because fish—people read and thought—is not filling. It is a “light” food, and for that reason “Lenten,” and can be thoroughly enjoyed only by those who do not have to deal with daily hunger. In both connotations, fish labored to achieve a positive nutritional value. It was eaten, and even abundantly, but culturally it always remained a surrogate for meat. “Taste” and “need,” Flandrin taught us, do not always go hand in hand.20

The revolution in fashion, which in the last century overturned this situation, bringing fish to the summit of positive values and spreading, by contrast, diffidence toward meat, signifies something very simple: we have evolved from a society of hunger into a society of plenty—from a society that lived in fear of an empty stomach (and for that reason sought, above all, filling and high-caloric foods) to a society that lives in fear of a full stomach (now oriented toward light and low-calorie foods). Lenten food has thus lost all meaning of renunciation, sacrifice, or penance. Fish has won the battle.