THE IMAGE OF MILK is naturally associated with infancy. It is a positive thing, a source of life and health. Ancient and medieval doctors defined it as a kind of whitened, purified blood.1 And blood is the very essence of life. It is therefore not surprising that milk also holds a place in religious symbolism as an image of life and inner salvation. In early Christianity, the holy meal of believers consisted of milk (along with bread or honey) and only later moved toward the ritual consumption of bread and wine.2 At a certain point, wine replaces milk in the cultural and religious imagination, taking over its functions. This happens when milk loses its primary nutritional value, as in the passage from infancy to adulthood.

The profound connection between milk and infancy, which stands at the origin of the positive values symbolically attributed to milk, is also the limit of its role and its image, preventing it from assuming an entirely positive alimentary, and cultural, value. As a food for adults, milk (and here we are speaking of animal milk) is generally rejected. According to ancient medicine, milk is not a suitable food for adult humans. Hippocrates and Galen advise it only for medicinal purposes, emphasizing its many dangers from a nutritional standpoint.3 These judgments were also made in the light of environmental issues: Greek and Roman culture developed in a geographic region, the Mediterranean, unsuited to the consumption of a delicate and perishable product such as milk. This was true in general but even more so in warmer climates, and it is not by chance that only certain populations to the north were described, not without amazement, as habitual milk drinkers. “Mare-milkers,” Herodotus called the Scythians, who were great consumers of milk and milk products.4 We see similar evaluations made by writers of late antiquity and the early Middle Ages. For example, Giordano, writing about the Goths, said that thanks to their contact with neighboring tribes, they discovered that marvelous drink of civilization, wine, but nonetheless remained faithful to milk, their traditional drink.5

The consumption of milk in adulthood thus became the alimentary characteristic of barbarianism—a notion analogous to infancy, transposed from the biological to the sociocultural: barbarians, who do not yet know “civilization,” are to “civilized” man what the infant is to the adult. The paradox is that among the alimentary habits of mankind, the ability to drink milk in adulthood is one of the most heavily weighted with a cultural connotation, representing the outcome of a long and difficult adaptation that altered, more than other habits, the natural behavior of the species, yet today remains negligible throughout the world.6 On a symbolic level, the image is reversed: milk drinkers are barbarian and primitive. This was the opinion of ancient and medieval writers who contrasted “evolved” agricultural societies with “primitive” pastoral societies and the foods developed and “invented” by humankind (such as bread and wine) with the foods spontaneously provided by nature (such as meat and milk).7

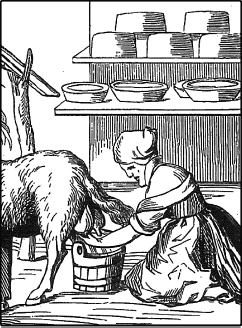

The milk in question is mostly ewe’s milk. In fact, whereas today it is generally taken for granted that animal milk is chiefly from cows, in ancient and medieval times the preferred milk ideally came from ewes or goats. Until the Middle Ages, cattle raising was marginal compared with that of “small animals,” as pigs and goats were called, because cattle were considered working animals rather than a source of food.8 Isidore of Seville, in the seventh century, in the chapter on animals in his monumental etymological encyclopedia, saw a preliminary distinction between two categories of animals: “those that serve to lighten the labor of man, like oxen and horses, and those that serve to feed him, like sheep and pigs.”9 Oxen were used to pull carts and to plow, certainly not to produce milk or meat.

This classification corresponded to food habits and was reflected in categories of diet and taste: the milk of ewes and goats was regarded as the best on the dual grounds of taste and nutrition. Fifteenth-century humanist Bartolomeo Sacchi, known as Platina, in summarizing widely shared concepts and evaluations, wrote, “Milk has the same characteristics as the animal from which it was drawn: goat milk is reputed to be excellent because it aids the stomach, eliminates occlusions of the liver, lubricates the intestine; second is ewe milk, and third is cow.”10 It remains understood that “the excessive use of milk is not advisable”—a view shared by the physician Pantaleone da Confienza, author of the oldest known treatise on milk and milk products,11 published in 1477. Milk, wrote Pantaleone,12 is recommended exclusively for persons in perfect health, with many precautions: “it must come from healthy animals, be of high quality and freshly drawn; it should be drunk, in all cases, on an empty stomach, or no less than three hours after the last meal, and immediately after drinking vigorous exercise should be avoided.” Furthermore, one must take care not to mix milk and wine in the stomach because the two are considered incompatible, based on the beliefs of traditional culture and for symbolic reasons as well.

It would nonetheless be a mistake to believe that milk had no place in the diet of medieval people. On the contrary, it played an important and at times decisive role in nutrition. Few drank milk, but the practice of turning it into cheese was fairly universal—and, moreover, an excellent means of assuring its long-term durability.

In truth, even with regard to cheese, medieval culture, like that of ancient times, remained very doubtful. The mysterious mechanisms of coagulation and fermentation were viewed with suspicion by medical science. Dietary treatises invariably expressed diffidence on the subject of cheese and warned against its consumption, placing many limitations on both quality and quantity. The greatest scientific authorities of the Greek and Roman world voiced these views, as did the Arab doctors who repeated them and transmitted them to western Europe. “Caesus est sanus quem dat avara manus [Cheese is healthful only when given by a miserly hand],” an aphorism attributed to the Salerno school of medicine, became a near commonplace in the literature on hygiene of the late Middle Ages.13 Only when cheese is eaten in small quantities is it not harmful to the health.

Aged cheese was the primary object of such negative judgments. Platina, mentioned earlier, condemned it because “it is hard to digest, minimally nutritious, not good for the stomach or the intestines, generates bile, brings on gout, pain in the kidneys, sand and kidney stones.” Fresh milk, on the other hand, “is very nourishing and in an efficacious way, it calms inflammation of the stomach, and is beneficial to people afflicted with tuberculosis.”14 Opinions like these recur insistently, almost as platitudes in medieval and modern treatises. They arise not only from theoretical prejudices (the processes of fermentation were often seen negatively in ancient cultures, and particularly biblical culture, because of their association with the corruption and putrefaction of organic matter) but also from practical considerations determined by the esthetic, gustatory, and olfactive characteristics of a product that not uncommonly—despite the massive amount of salt used to preserve it—looked rotten.

Medieval dietetics—based on the Hippocratic-Galenic theory of the four “qualities” (hot, cold, dry, and moist), according to which it is possible to classify foods in an infinite variety of combinations and “degrees”—set itself the task of arriving at a balanced diet that reconciled excesses by means of opposite excesses, taking into account not only the quality of the food but also the variables of the environment (location, climate) and the nature of the consumer (state of health, kind of life and work, sex, age, and so on). In conjunction with this kind of equilibrium, suggestions were made concerning combinations, type of cooking, and order of dishes. As for cheese, Platina maintained that it should be eaten at the end of the meal “because it seals the mouth of the stomach and eliminates the nausea caused by fat foods.”15 This “sealing” ability of cheese, proclaimed by the Regimen sanitatis of the Salerno school (“eaten after the other foods, cheese signals the end of the meal”)16 and repeated for centuries by dietitians, is the origin of customs still practiced today, not to mention proverbs, that do not consider a meal to be finished “until the mouth tastes of cheese.”17 It is interesting to note how proverbial traditions often take root in a premodern dietary culture in which the scientific particulars have disappeared but the practical precepts remain vigorously present.18

The recommendations of the doctors, in the case of cheese as of every other alimentary practice, found immediate and direct confirmation in the uses suggested by cookbooks of the time. Maestro Martino, the most important cook of the fifteenth century—whose close intellectual affinity with the Roman circles frequented by Platina19 has recently come to light—makes a point of specifying that “cheese in little pans [caso in patellecte],” for which he provides the recipe, “should be eaten after the meal and very hot.”20

All this, naturally, concerns only the small segment of society that has the luxury of choice. Every reservation falls by the wayside when it comes to need, when hunger imposes its own reasoning: “The poor, and how many are forced by necessity to eat cheese every day, are not obliged to observe the rules that we have set forth, being forced to eat cheese at the beginning, end and middle of every meal,” wrote Pantaleone da Confienza without irony.21

Let us pause on this association of the poor with the consumption of cheese. It goes back to antiquity, as seen in the pages of authors and agronomists, from Cato to Varro, Columella, Pliny, and Virgil. In most of these texts, the social level that consumes dairy products seems decidedly “poor.” Columella, however, points out a difference: cheese “serves to feed peasants” (in fact, it “fills them [agrestis saturat]”), but “it graces elegant tables.”22 On the tables of the poor, it is a main dish, a primary source of nourishment; on the tables of the rich, it appears only as an “embellishment” or an ingredient in more complex dishes.

This image carried over in part into the Middle Ages, framed however in a process of “ennobling” the product that led ultimately to a reversal—the definitive recognition of the economic, alimentary, and cultural value of cheese. A process of this kind, not without ambiguities, centered around the monastic alimentary model, hardly representative of the majority but nonetheless capable of imposing itself on the whole of society as an ideal reference point, being highly prestigious, and having great impact on the definition of collective behavior and attitudes. The essential element of the monastic model is the renunciation, partial or total, of meat. Prohibited to monks out of principle, albeit with many exceptions, meat was replaced by such substitute foods as fish, eggs, and cheese. Extending well beyond the monastic world, such renunciations (and such substitutions) came to be imposed by church regulations on the entire Christian society and ended up covering a good part of the year—as much as a third or more, as we have seen.23 These choices and these requirements brought about important changes in the diet and in the “social status” of products. If, on the one hand, cheese was confirmed as a food of the poor and a substitute for a more prestigious and desirable food, on the other hand, it became “ennobled,” reaching top billing in the diet, an object of the most concentrated attentions and, on occasion, of experimentation and innovative research. Almost paradoxically, the culture of renunciation was itself the origin of a new gastronomic culture, of an inquisitive and creative nature, from which many future acquisitions of taste arose. “Is it possible to single out any esteemed cheese that was not monastic in its distant past?” asked Moulin.24 This is surely an exaggeration because those “origins” are often no more than mythic. But myths are themselves indications of a cultural climate, a common attitude that identified monastic centers—“the sites of renunciation”—as the sites where, paradoxically, gastronomic culture developed.

Moreover, when we speak of “monastic gastronomy,” we must not forget the centrality of the peasant world in the evolution and diffusion of that culture. If monastic cheeses came to be produced and perhaps even “invented” within the monastery, this took place with the collaboration of the rustics who worked for the monks. In other cases, and perhaps in many, cheeses came from without, from farms that the monks owned but that others tended. The income in kind that the monasteries received from their tenants often included certain quantities of cheese. The monastery of Saint Julia of Brescia—as we know from the inventory of its holdings, drawn up in the ninth and tenth centuries—collected sizable rents in cheese from peasants living on monastic properties in Lombardy and Emilia. Requests were expressed in weight, with an indication of the corresponding pounds of caseum, or in the number of wheels.25 Similar attention to cheese can be found in another ninth-century monastic inventory from the abbey of Saint Colombano in Bobbio, on the Emilian Appenines.26 We have to imagine the fertile encounter of opposing parties: the long-established experience of peasant-shepherds confronted with the self-interested requests of the landowners to diversify and renew that experience.

In medieval gastronomic culture, cheese thus acquired—despite medical advice—a major renewal of image, a social boost that made it increasingly acceptable on elegant tables. In the fifteenth century, Pantaleone da Confienza could write in the Summa lacticiniorum that he knew “kings, dukes, counts, marquesses, barons, soldiers, nobles, merchants” who often and willingly ate cheese.27 This direction will continue to affirm itself in the Renaissance and in modern centuries, when even literary and poetic works will sing the praises of cheese, such as the sixteenth-century triplets of Ferrara writer Ercole Bentivoglio.28 The presence of cheese on noble tables is confirmed during those centuries by cookbooks, such as the one by Cristoforo Messisbugo, chef to the Este court in Ferrara, who lists “ricotta, cavi di latte, gioncata, cream, butter; hard cheese, fat cheese, tomini, pecorino [ewe’s milk], sardesco [Sardinian cheese]; marzolini, provature and ravogliuoli [types of cheese]” among the indispensable provisions “to set a proper table for the arrival of any great prince … or for any other important event that might take place.”29 The vicissitudes of cheese demonstrate with singular clarity how values typical of popular culture can rise to the upper ranks of gastronomy30—an example of integration from bottom to top, not uncommonly paralleled by the reverse or, better still, by reciprocity and circularity.

Cheese was also widely used in cooking. As Platina tells us: “cooks used cheese in the preparation of many foods.”31 Its use is amply documented in the cookbooks of the time, between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when they first appeared in Italy and other European countries.

Fresh cheese was mixed into eggs, meat, vegetables, and fragrant herbs to make all kinds of tortes and pasties—perhaps the dishes most characteristic of medieval gastronomy. The thirteenth-century cookbook preserved in a miscellaneous codex in the library of the University of Bologna, known as “Anonymous Tuscan”—cited here only as an example—proposes “fresh cheese [cascio fresco]” for the filling of “meat crepes or tortelli and ravioli,” as well as for the stuffing of a lamb shoulder that must also include “fresh cheese, well blended with a fair amount of eggs.” Along with “chopped meat,” fresh cheese should go into pastello romano, whereas the torta parmesana should contain, in addition to fresh cheese, “an equal amount of grated cheese.” This last ingredient also goes into “stuffed [deviled] eggs” and, of course, into lasagne.32 In other cases, cheese is the principal ingredient of the dish and the qualifier of its name: a casciata* is made of “fresh cheese washed and well drained, finely broken up with the hands in a bowl, then blended with eggs, herbs, lard, salt and pepper and baked in a crust.” This is assuredly simple cooking, presumably of peasant origin but destined for the upper classes, as is made explicit in this cookbook, which, like all the others, was intended for the nobility or urban upper bourgeoisie. After the recipe for cascio arrostito (cheese roasted on a skewer over the open fire and served on a thin slice of bread or placed on a board of dried pasta), the writer of the text directs, “and bring it to the lord.”33

Aged cheese also entered into cooking, as we have just seen in the recipes of the anonymous Tuscan. Although the fresh cheese was ground (with mortar and pestle), the aged one was grated, as the cookbook of Maestro Martino makes clear regarding a torte of spelt: “Take a pound of fresh cheese, and half a pound of good aged cheese, grinding the first and grating the other, as is customary.”34 In recipes for salty or sweet tortes, the two types of cascio, singly or mixed depending on the dish, are the principal ingredients.35 They also make their appearance in fritters,36 omelets,37 and “deviled” eggs,38 as well as in many other dishes.

Among the grating cheeses, parmesan, already in the Middle Ages, had acquired indisputable primacy (although at that time piacentino and lodigiano (similar cheeses from Piacenza and from Lodi) were equally famous.39 The success of this kind of cheese, which was exported outside of Italy as early as the fourteenth century,40 is also connected to the renown of a manufactured product that went particularly well with it: pasta. It is to parmesan, in all probability, that Salimbene da Parma is alluding in his thirteenth-century Cronaca when describing a monk, Giovanni da Ravenna, as a great lover of lasagne with cheese: “I never saw a man eat lasagne with cheese as eagerly as he.”41 And Boccaccio lavishly described as one of the major attractions of the utopian Land of Bengodi “the mountain made entirely of grated parmesan atop which people stood doing nothing but make macaroni and ravioli and cook them in capon broth.”42

The practice of sprinkling parmesan on pasta, mixing in butter and sweet spices, is regularly documented from then on in treatises and literature, in chronicles of banquets, and in the recommendations of cookbook writers. Maestro Martino wants it on ravioli, Sicilian maccheroni, vermicelli, and lasagne and even on liquid first courses such as manfrigoli.43 A novella by Celio Malespini, at the beginning of the sixteenth century, brings together a group of Venetian gentlemen who are delighting in macaroni from Messina seasoned with “more than twenty-five pounds of parmesan, and six or eight of caciocavallo [a type of provolone, the size of a fist, made in southern Italy], along with innumerable spices, sugar, cinnamon, and so much butter that they were drowning in it.”44 These are luxuries not available to the poor, who were limited to imagining them in their dream of Bengodi, that happy land of Boccaccian memory. Many people called it the Land of Cockaigne and perhaps believed it to be real. “They left with all their belongings and families,” related a chronicler from Modena, Tommasino de’ Bianchi, on the subject of certain peasants who fled beyond the Po in search of work, “and went to stay in Lombardy … because it is said that there they hand out gnocchi covered with cheese, spices and butter.”45

Until the eighteenth century and its happy marriage with tomato sauce, pasta was customarily seasoned with butter, spices (chiefly cinnamon), sugar, and cheese. But not even tomatoes managed to replace cheese completely. The Neapolitan Ippolito Cavalcanti, who in the 1830s provided one of the first recipes for macaroni and tomato sauce, proposed that the macaroni, barely drained, should be well covered with cheese before adding the tomato sauce: “mix in aged cheese and provolone; and no matter how many other cheeses you may choose to add, they will only make it tastier.”46

By the end of the Middle Ages, the traditional superiority of ewe’s milk over cow’s milk was no longer taken for granted. “At the present time,” wrote Platina around the middle of the fifteenth century, “there are two varieties of cheese that are contesting primacy: marzolino, as the Tuscans call it, made in Tuscany during the month of March [marzo], and parmesan from the regions south of the Alps, that could also be called maggengo made in May [maggio].”47 In fact, these differing times conceal a much deeper opposition, curiously not emphasized by the author: cheese made of ewe’s milk versus cheese made of cow’s milk. The growing success of parmesan was the proof of a culture that had begun to diversify and of a product that in some regions of Italy—“cisalpine,” Platina calls them—had gained such strength that it could “contend the primacy” of the traditional cheese of ewe’s milk. This became generalized in continental Europe during the late Middle Ages and early modern era. In Italy, beginning in the fifteenth century, the irrigated plains of the Po and the high pastures of Alpine valleys took on primary importance for raising dairy herds.48

In the meantime, regional specialties diversified and increased. In the sixteenth century, Ortensio Lando proposed a kind of “gastronomic itinerary” that stopped for the fresh caciacavalucci of Sorrento, the ravigiuoli of Siena, the marzolini of Florence, the ricottas of Pisa, and the cacio piacentino, which he remembers having eaten in Piacenza with apples and grapes and finding himself “consoled as though I had eaten a superb pheasant.” Among the cheeses from the Po Valley, “the cheese of Malengo and from the Bitto valley” was also praised, and a final mention concerned cavi di latte (a cream-based dessert) from Venice.49 Cow’s milk cheeses held a position of great importance in the already mentioned Summa lacticiniorum by Pantaleone da Confienza, whose intention—called promotional in the language of today—was primarily to praise the gastronomy of the Po Valley and, in particular, that of Piedmont and Savoy. The cheeses of southern Italy and the islands, much appreciated and widely commercialized at that time,50 are not even mentioned by him. That such a project was even conceivable marks a significant turning point that took place in the fifteenth century. Like Platina earlier, Pantaleone singles out as the best cheeses in Italy the marcelinus, or marzolino, also called fiorentino, produced in Tuscany and Romagna, and the piacentino, also called parmigiano (so identified by Platina) “because in Parma they make similar ones, not very different in quality.” In the regions around Milan, Pavia, Novara, and Vercelli, they also began to produce some “a few years ago.” The first is made of ewe’s milk, “although some add cow’s milk”; the second is of cow’s milk.51 It is, above all, this latter that in the centuries to come would cross the borders of Italy and become one of the signal traits of its gastronomic image.