THE CHESTNUT, which grows spontaneously in a large area of the Mediterranean climate zone, remained outside the borders of commerce for a long time. At first, the Greeks did not even have a name to designate the chestnut, regarding it as a particular species of acorn or walnut.1 Roman agronomists gave it little attention. Columella devotes a brief paragraph to the cultivation of the chestnut,2 and Pliny the Elder makes note of “numerous varieties,”3 but dietary science continued to refer to the wild species: “among all wild fruit,” Galen wrote in the second century, “only chestnuts provide a significant amount of substances that are nutritional for the organism.”4

This situation lasted throughout the high Middle Ages: when documents make mention of the chestnut, it is hard to determine whether they refer to wild or cultivated trees.5 This holds true, for example, in the Longobardic law: “If someone cuts down a chestnut tree, a walnut tree, a pear tree or an apple tree, he must pay a fine of one soldo” (Edict of Rotari, A.D. 643).6 It was only in the middle centuries that the chestnut was widely cultivated and became an important source of subsistence. The change occurred in the tenth and eleventh centuries in conjunction with an increase in population and a need for food. In regions of plains and hills, the expansion of cultivation increased at the loss of the woodland that had previously been the primary element of the landscape. In mountainous zones, where grains are hard to grow, chestnut groves took their place. The two phenomena developed in a perfectly parallel way: fields of grain and plantations of chestnut trees grew at the same rate.7

Between the eleventh and thirteenth centuries, the spread of chestnut groves continued throughout the Appenine region of Italy, from Emilia to Tuscany, from Umbria to Lazio, and as far as Campania.8 The same thing took place in south-central France, Spain, and Portugal and on the Balkan peninsula. Everywhere woods were transformed, becoming “domesticated.” The forest-pastoral economy (i.e., herding and hunting), which in the early centuries of the Middle Ages had been the prevailing “natural” use of the forest, gave way to a new type of forest economy, more similar to agriculture in view of the constant care required to plant and maintain the chestnut groves. An Italian example: the forest of Santo Stefano, communal property of Mondovi in Piedmont, was leased in 1298 to fifteen individuals who, for an annual fee of fifty lire, contracted to make it fertile and fruitful. How? In part by tilling it and turning it to agriculture and in part by transforming it into chestnut groves: on that sterile and infertile terrain could be planted “multa bona et domestica castagneta [many good cultivated chestnut trees].”9

This “domestication” often took place at the price of oak trees. On the alimentary level, this produced a radical change in the popular diet, which increasingly turned from meat (pigs and game) to chestnuts, as that in the plains turned to grains. In both cases, a starch, a vegetable product, was chosen over meat because of its greater yield in weight and perhaps its greater adaptability in use. These were choices dictated by hunger, which followed side by side with the increase in population and expanding settlements. The chestnut became a “mountain bread” that replaced “genuine” bread where the latter could not be obtained: it was called “tree bread” in the region of the Mediterranean, and the chestnut tree came to be known as the “bread tree.”10

This capacity to serve as a substitute is explicitly documented in many examples. In 1288, Bonvesin de la Riva, writing about the alimentary customs of Lombard peasants, said: “Often [chestnuts] are eaten without bread, or rather, in place of bread.”11 “Chestnuts are the bread of poor people” appears in a Tuscan statute of the fifteenth century.12 Statements like these become more prevalent with the passage of time, as the alimentary conditions of the lower classes worsened. “In places where there is little grain, [chestnuts] are dried on grates over smoke and then ground to make flour, which is the substitute for making bread,” explains Castor Durante in 1586.13 Literary sources provide similar information: an anonymous poem from the end of the sixteenth century, describing the customs and hardships in the life of the inhabitants of the Tuscan Appenines, states that up there “bread is made of chestnuts.”14 In the seventeenth century, Giacomo Castelvetro, from Emilia, confirms this: “Thousands of our mountain dwellers eat this fruit in place of bread, which they never, or rarely ever see.”15

Even with regard to nutritive value, one can see a certain resemblance between chestnuts and grains. Piero de’Crescenzi, the most famous Italian agronomist of the Middle Ages, returns to an opinion expressed in medical and dietetic treatises, quoting Galen, when he writes that the chestnut “is the most nutritious of all seeds insofar as it is the closest to the seed for bread.”16 The Spaniard D’Herrera confirms that chestnuts, “after wheat, give more sustenance to the body than any other bread.”17 Vincenzo Tanara as well, in the eighteenth century (invoking the authority of Galen), says that bread made with chestnut flour “aside from that made of wheat, is more nutritive than any other grain.”18

In truth, as a substitute for bread, the chestnut is closer to the inferior grains than to wheat, whether because of the similarity of alimentary uses or because of its social destination—the lower classes, in particular. Bonvesin de la Riva, quoted previously, maintains that chestnuts, beans, and foxtail millet replace bread in the diet of many peasants. For the year 1285, the chronicle by Salimbene of Parma notes “the scarcity of small grains and chestnuts.”19 Indeed, the chestnut tree became a primary resource for many mountain communities, a genuine “plant of civilization”20—alongside and in place of wheat—around which local life and culture rotated.

Technical expertise for the planting and cultivation of chestnut trees was transmitted by example and by practice but also by written texts. Contracts with growers occasionally indicate with great precision the operations to follow. In 1286, two men from the mountain area near Bologna rented a property, contracting to prune the chestnut trees and cut old logs and to graft new suckers so as to increase production by using a specific variety of plants. The earth was to be plowed, tilled, and fertilized; for the first harvest, they would pay a reduced fee, barely equal to a fifth of the product. As production increased, they would pay half, according to the typical model of sharecropping contracts.21

Certain agronomists of the modern era recommended starting the trees from seed: “to have enough pairs [of chestnut trees] it is better to start them from seed than to plant them,” performing the operation during the month of March and selecting a terrain “well spaded, well cleaned, and well mixed with manure” (so says Agostino Gallo from Brescia in the sixteenth century).22 But a much older and more widespread practice is to plant seedlings, according to the classic dictum of Columella: “planting begins in the month of November.”23 Also widespread are the practices of grafting and suckering on old stumps, which we just saw in the document of 1286. Along with the labors of pruning and husking went the protection of the land against the outflow of water. As for manuring, Tanara in the seventeenth century recommends fertilizing the trees only with “their own shells.”24

Particular attention is given to chestnut groves and to chestnuts in the statutes of rural communities, collectively involved in the protection and valorization of this precious resource. Special officials—in some cases paid in kind, meaning in measures of chestnuts—are charged with overseeing the forests and protecting them from damage caused by men or animals. Grazing under the trees is rigorously limited and at certain times of the year prohibited. The dates for harvesting, determined by the communal government, must be observed and apply to all. The conflict between the cultivation of chestnut trees and herding is particularly critical in communal regulations, which generally try to conciliate the two requirements in the hope of finding a balance that is difficult but not impossible. The statutes of Sambuca (in the Apennine region of Tuscany and Emilia) prohibit pig farmers from being found with their animals in the chestnut groves or in the nearby oak stands until the commune has officially proclaimed the end of the harvest (abandonamentum), after which grazing and digging—that is, gleaning under the trees—are permitted. Pig farmers could take their animals along the road going downstream only ten days after the chestnuts had fallen, keeping the herd close together and seeing to it that they did not go more than ten arm lengths beyond the path. In turn, the owners of the chestnut groves committed themselves to gathering the chestnuts before the passage of the pigs. The dates of access by the animals varied from place to place, depending on times of harvesting, which in some places continued through December.25

At times, instead of waiting for the chestnuts to fall spontaneously, the harvesting was anticipated by beating the trees with long poles. Both possibilities were foreseen by de’Crescenzi: “The chestnuts are gathered when their burrs fall to the ground, or else, when the burrs begin to appear the trees are beaten with poles.”26

The importance of chestnuts in the diet of the poor was related to the fact that chestnuts could be stored for long periods. If the harvest was good, subsistence was assured for many months. “In our mountains,” Gallo wrote, referring to the pre-Alpine region of Lombardy, “an infinite number of people live on nothing but this fruit.”27 In 1553, the captain of the mountains of Pistoia noted that the inhabitants of the village of Cutigliano “are so desperately poor that seven-eighths of the year they eat only castagnacci.*,28 This was also the case in many European countries: in certain regions of France, the daily consumption of chestnuts was estimated at two kilos (almost four and a half pounds) per capita for six to seven months a year.29

Clearly, this was possible because of perfected techniques of conservation but also because of the astute diversification of the various cultivars, which allowed for successive times of growth. For centuries, this was a fundamental strategy to protect the system of production, also entering into the choice of grains,30 thereby better assuring that the needs of the peasants were met within the limits of an economy constantly suspended between the satisfaction of needs and the scarcity of resources. For chestnuts, like grains, growth times were varied so as to extend as long as possible the period of harvest. By this means, they managed to obtain harvests over a much longer period than is normal today.31 The inhabitants of Mount Amiata, in southern Tuscany, were described in the medieval statutes of the region: “They only harvest chestnuts, and they are busy with that from September well into December so as to survive and sustain themselves throughout the year.”32

As to techniques of preservation, which preoccupied agronomists beyond the daily practices of the peasants, there were principally two systems: keeping the chestnut fresh inside its burr and drying it in the sun or in the heat of the fire. The first system was described by de’Crescenzi, who recommended beating the chestnuts out of the tree when they are still green. Then they are gathered and “piled up inside a bush, to keep them from the pigs. And when they have been closed up this way for a few days inside their burr, they open up, and these are the best ways to keep them fresh … inasmuch as they can be kept green all of March.” Instead, if they are gathered on the ground already ripe, “they will keep barely two weeks.”33 Unripe chestnuts can also be kept “in sand,” as de’Crescenzi34 informs us, and in the sixteenth century, Gallo advises: “Whoever wants to preserve these fruits should gather them by a waning moon when they are half-ripe and completely dry, and place them in sand in a cool place, or, still in a cool place, in some kind of crock that is so tightly closed it does not allow any air to enter, otherwise in a short time they will rot.”35 Considerably later came the method of “curing,” which involves immersing the chestnuts in water for a few days, causing a light fermentation. No agronomist makes mention of this until the eighteenth century.36

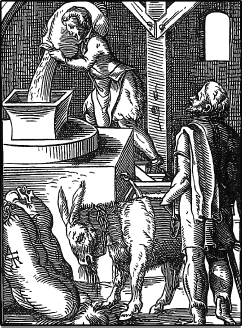

When drying was used, it took place in the open in special buildings situated within the chestnut grove. The chestnuts “no sooner gathered are placed on a grate under which smoke is made and a fire is kept going for many days until they are completely dry, as dry as stones,” Tanara explains.37 Castelvetro explains that when dried by smoke on grates and then peeled, “they can keep for two years and more.”38 Sixteenth-century texts replicate medieval practices. The fruits, kept semifresh, were eaten whole: “Our women,” Castelvetro explained, “keep the chestnuts in baskets or in boxes with rose leaves, where they become tender and very fragrant.” Those that were dried were successively ground to make flour. In certain mountainous regions, mills ground chestnuts exclusively, and in payment, the millers received a portion of the ground chestnuts.

The chestnut was first and foremost a product of subsistence intended to fight hunger among the poor in mountainous areas. Its presence was less prevalent in the plains, and, more generally, in the cities chestnuts were consumed more as a delicacy than a necessity. Even in this instance, the product’s importance was related to its particular aptitude for conservation, which made possible its prolonged presence on the market. Documentation from the mid-fourteenth century indicates that even in the month of May “fresh chestnuts, candied chestnuts, dried chestnuts” could be found for the prestigious table of the priors of Florence.39 A few centuries later, Tanara observed that chestnuts could be served even in the summer “out of eccentricity.”40 The two aspects (need and whim, hunger and “eccentricity”) are not mutually exclusive; rather, they reinforce the story, which can be seen in the sixteenth-century statutes of the town of Popiglio, in the Tuscan Apennines: the inhabitants extracted from “the chestnut groves and the forests” both “the daily requirement for their food” and “the necessary money to face their every debt, whether public or private.”41 This means that they sold the chestnuts.

The preservable qualities of chestnuts were obviously most appreciated on the commercial level, and during the Middle Ages, these qualities were singled out in different varieties.42 In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, chestnuts from Lombardy were on the markets of Paris, and those from Campania went as far as Egypt and Constantinople.43 Foreign export was controlled by the merchants of major cities, who got their supplies from local marketplaces. For example, the chestnuts from the Apennines of Romagna ended up for the most part in Venice and from there went to the markets of the Levant.

The urban merchants sorted the local production, selecting a part of it for foreign export and a part for local consumption. At times, the commerce was in the hands of specialists, as in Treviso, where the produce vendor Diana, in the middle of the fourteenth century, contracted with the peasants of the region to secure for herself in advance the harvest of their chestnut groves; she sold a portion of the chestnuts in the city and sent the rest off to Venice.44 The trade went on for some time, at least four or five months, until well into the winter.

The needs of hunger and those of the market occasionally came into conflict—or at least into competition. This is why in periods of famine the exportation of chestnuts could be prohibited. A ban in Bologna in 1593, which attested to a good harvest “of marrons and chestnuts … allowing for the hope that the poor will have an abundant supply,” prohibited the product from being appropriated by merchants and leaving the territory; if by chance the harvest exceeded the need, it could be sold only “in the markets of the province of Bologna or in the marketplace of that city.”45

Roasted, boiled, or fried, chestnuts of regular dimensions were consumed fresh or semifresh, preserved within their burr or in sand. These latter were tenderized, Tanara explains, “by soaking in rose water,” and even better, “if they are interspersed between these same roses in May” they taste like fresh ones and are “eaten with delight.”46

The way to prepare chestnuts is well described by Castelvetro in his little opus on all the fruits and vegetables of Italy (composed in England in 1614). In his native country, he explains, “most people when cooking them roast them in a pan with holes on the flame of the fire or under hot ashes, and eat them with salt and pepper.” He further adds that in Italy they are flavored with “orange juice” but not with sugar “as they do here [in England].” Boiled chestnuts, he considers more plebeian: “they are eaten more readily by children and the lower classes than by civil and mature people.” He also mentions the custom of stuffing poultry with chestnuts: “Having left them to soak in fairly hot water, the second shell is removed and then various dishes are made, by cooking them in cream; and they are very tasty; and they are used to stuff the capons, geese, and turkeys that they wish to roast, with dried plums, raisins, and bread crumbs.”47 These are customs that the Europeans successfully passed on to the American continent.

The practice of steeping chestnuts in orange juice was already documented a century earlier by the physician Durante: “Lightly cooked in embers and peeled, they are then cooked in a pan with oil, pepper, salt and orange juice” (with the enigmatic specification that in this way “can serve as truffles”).48 But even the use of sugar—contrary to what Castelvetro seems to imply—was common in seventeenth-century Italy: for the month of November, Tanara proposes a recipe for “marrons cooked in embers, served with salt, sugar, and pepper on top.”49

These choices of flavorings are strictly related (as are so many others) to dietetic ideas. Tanara himself informs us that the roasted chestnuts “served with salt and pepper, are also served with sugar, whose presence makes them healthful.”50 The idea also appears in medical texts that justify this scientifically. According to Durante, “chestnuts roasted under embers and eaten with pepper and with salt, or with sugar, are less hard to digest.”51 Mattioli broadens this by explaining that roasted chestnuts “eaten with pepper and salt, or with sugar” lose all their noxious properties.52

Tanara lists many other ways of preparing chestnuts. For example, “placed in sweet wine they are delicious, and if the wine is new, all the better, but one has to have a strong stomach.” Or chestnuts, once cooked, “can be cooked again with pork, and are tasty when mixed into a soup made with vegetables, in particular with the white beans with which ravioli are made. … Chestnuts are also good with cheese and with milk,” and can be cooked in wine and dried in embers. A particular preparation from Piedmont is to cook them in wine with fennel, cinnamon, nutmeg, and other spices, “but first the outer shell must be removed,” and served hot.53

Dried chestnuts, on the other hand, are used after they have been ground into flour, with recipes of every kind that faithfully follow the various preparations of cereal flours. We have some from as early as the fifteenth century when Bartolomeo Platina—in his book on guiltless pleasure and good health, drawing for the gastronomic part on the most famous cookbook of the time by Maestro Martino—included a recipe for a chestnut pie (Torta ex castaneis): “Boil the chestnuts and grind them in a mortar, pass them through a strainer with a small amount of milk and than add the ingredients for a spelt tart.† If you want to give it some color, add some saffron.”54 Bartolomeo Scappi, the chef of Pope Pius V and author of the most important work on Italian cuisine of the Renaissance (published in 1570), included among the elegant recipes in his book two recipes that use chestnuts and chestnut flour: one is “a pie of fresh and dried chestnuts” for which he advises chestnuts not yet ripe, gathered in the month of August; the other is a “soup of chestnut flour.”55 These are recipes that seem to go back to peasant cooking, reinterpreted with more complex procedures and expensive ingredients: the addition of generous amounts of butter, sugar, and Oriental spices (cinnamon and pepper) suffice to make these preparations worthy of an opulent table. Nonetheless, their “peasant” nature is not entirely eradicated, testifying perhaps to an unexpected proximity between peasant cooking and upper-class cooking, despite the prejudicial ideological opposition between the two worlds, evolved from aristocratic culture dating primarily from the fourteenth to the sixteenth century.56

Regarding this proximity, the presence of chestnuts in elite cookbooks is one of the most obvious clues. They are found everywhere, from Italy to France to Spain. For example, a recipe for castanas piladas, enriched with costly spices (cinnamon, cloves, ginger, and saffron, mixed, however, with oil and onion), appears in the Libro del arte de cocina by Domingo Hernandez de Maceras, published in 1607 in Salamanca.57 Even books on pastry make use of the chestnut, or rather the marron: Le confiturier françois (published many times in the second half of the seventeenth century) lists a delicate compote de marrons, made of “marrons cooked in embers, apricot syrup, and Spanish wine.”58

Interesting recipes for desserts are provided in the seventeenth century by Tanara. It is delicious to mix into chestnut flour, dissolved in rose water, parmesan or some other tender fat cheese and “then make castagnazzi in the shape of fritters, fried in a pan with butter” (a variant adds honey to the flour, “for flavor, and health”).59

Dietetic science not only contributed to the definition of certain types of condiments for chestnuts aimed at minimizing their presumed ill effects but also provided the guidelines for the proper place of these products within a meal. Because astringent properties were attributed to chestnuts (Mattioli: “they constipate the body”; Durante: “they constipate”60), it was concluded that the right time to consume them was at the end of the meal to “seal” the stomach, which had previously been “opened” by such acidic fruits as citrus fruits. “Chestnuts are astringent … if eaten after a meal”: this incontestable declaration by Tanara61 brings together observation and practice consolidated over centuries. At the end of the thirteenth century, after having provided detailed directions for the gastronomic use of chestnuts in the region of Lombardy, Bonvesin de la Riva points out that “they are generally eaten after other foods.”62 In the same period, in 1266, a curious agrarian contract drawn up in the region of Asti by one dominus Pacia stipulated that the tenants were responsible for two annual dinners, which were to begin with a lemon, followed by various meats accompanied by appropriate sauces and a dish of vegetables, and to end with a “paradise fruit” and six chestnuts.63