THAT THE DINING table is one of the best places for communication—perhaps the ideal place, where the desire to communicate with one’s familiars is expressed with ease and freedom—is so evident and so readily observable in daily life that there is no need for historical confirmation. We shall therefore concern ourselves with the table not as a place but rather as a means of communication by analyzing some of the forms and modes with which this convivial ritual, this fundamental gesture that guarantees and celebrates daily survival, makes itself the bearer of all kinds of signs and meanings.

This is brought about by the collective dimension of this gesture, which for that alone acquires a linguistic and communicative content because every gesture enacts with others, in front of others, affecting its essential nature (in this case, eating), and enriching it with symbols and values of circumstance, as Barthes put it.1 And given the fundamentality of the gesture in question, its primary importance deriving from the preservation of life, the symbols and values it projects are also of primary importance and intensity. The dining table, where life nourishes itself, becomes the perfect means for affirming (or negating) the meanings of life—in particular, those meanings that concern life with others, either confirming or, on occasion, revoking them. Above all, this kind of interpersonal dimension springs out of the convivial ritual, in view of the collective character of the gesture, which seems ingrained in human nature: “We,” Plutarch has one of his characters say in his Table Talk, “do not invite one another merely to eat and drink, but to eat and drink together.”2

The convivio (banquet table) is thus a metaphor for the identity of a group or of life together—literally, cum vivere.3 Living together does not necessarily imply harmony of intentions or affections, as the reality and terminology of “convivial” are too often misunderstood. The banquet table, like life, is a neutral place where everything, and the contrary of everything, can take place; even tensions and conflicts find their ideal environment, not only because the banquet hall is technically the ideal place for assassinations and poisonings but also because it is metaphorically the most meaningful, the most resonant sounding board for amplifying everything that happens in the order of things and the relationships between people—separations and betrayals, no less than friendships and alliances. It is at the table, for example, that Mauro, son of a nobleman from Amalfi, is betrayed by Gisulfo, duke of Benevento: “At first Gisulfo treated him with honor … and had him eat with him. Then, he had him removed from the table and imprisoned in his room.”4

Although the banquet table expresses the identity of the group, it also expresses, within that context, the underlying relations of strength and power. Further, it expresses the “difference” of those who are not invited. A metaphor of the community, of its internal harmonies and external relations, the banquet table is the place of inclusion, as well as exclusion. Expulsion from the communal table represents the first and most significative form of excommunication for the monk who is stained with wrongdoing. To eat in solitude, according to the Benedictine Rule, is a sign of guilt and a means of expiation.5 For the layperson as well, “excommunication” involves solitude and exclusion from the communal table, and no one can eat with someone who has been excommunicated without himself incurring the same punishment. This, Odo of Cluny relates, is what happened to the King of England for having eaten with two Palatine counts who had been excommunicated by the bishop.6

No less evident are the power relations within the group that sits together at the banquet table, as already seen in the modality of participation at the communal table.7 This can be the symbolic place of collective solidarity in which one participates by virtue of being a part of that group. We see this in the monastic community, in the ritual gatherings of lay corporations and confraternities, or even more simply, within the nucleus of the family, described by certain medieval documents as the collectivity of those who live “by the same bread and the same wine.”8

In other cases, being at table together is the result of an invitation. Then a differentiating mechanism comes into operation that places on an unequal level the one who invites and the one who is invited. The significance of this gesture has diverse values—and even contrary ones. If the invitation is freely made—that is, voluntarily—it can place the guest in a situation of objective debt and thus of inferiority (a situation that rights itself with reciprocity or a counter-gift, common in the field of anthropology).9 In this case, to invite people to one’s own table is a sign of liberal generosity, of economic well-being, and in the final analysis, of power: an invitation is a gesture of self-affirmation and therefore all the more impressive as the number (or rank) of the people gathered around oneself increases. In the banquet hall of Emperor Frederick II, 18 people were received at his table on a regular basis, but another 162 were seated at tables in a smaller dining room nearby.10 The table of Henry VI, who “defied the rule of numbers,” was described by Pietro da Eboli in song.11

The significance of the gesture changes totally when the invitation is not voluntary but obligatory, indicating a situation of dependence, of social inferiority on the part of the host. Such is the meaning of the meals that many peasants were obliged to offer their lord or, more commonly, to his agents when they came to inspect the agricultural operations and the sharing of products, and to ensure correct payment of the rent. Once in a while, one comes across extraordinary documents, such as the lease drawn up in 1266 at Asti between two small farmers and a person significantly titled dominus Pancia, who requests the payment of two dinners for two as annual rent—one in January, the other in May—with a menu minutely described in the document.12 But the more common payment of “donations” (obligatory, however), consisting of food and alimentary products, does not seem to have a different meaning. That, too, expresses an obligation of gratitude—in other words, a state of subordination and social inferiority. It is to this end that flat breads (focacce), chickens, and eggs were generally stipulated in agrarian contracts.13

The inherent symbolism of those offerings and those invitations, defined from time to time by precise rules of decoding, explains why medieval documentation is so rich in disputes over the payments of dinners and suppers, in which the core of the contention has less to do with furnishing one or two piglets to the presiding individual or institution than with the significance attributed to that payment: Was it voluntary or compulsory? A sign of power or subordination? A complicated affair of dinners required but not provided was at the origin of a quarrel in the twelfth century between the Bishop of Imola and the head of the city’s cathedral.14 The monks and canons of the cathedral of Saint Ambrose in Milan were involved in a similar conflict.15 Yet another dinner was disputed by the priors and clerics of the church of Saint Nicholas in Bari, as we know from an inquest conducted in 1254. Traditionally, priors offered canons a convivium (banquet) right inside the church.16 In the relation between persons or (in these cases) interested parties, the meaning attributed to the offering of food or to the invitation to dine was the decisive factor, and the judges called in to settle the differences found themselves faced with delicate exegetic problems, resolved after careful examination of witnesses.

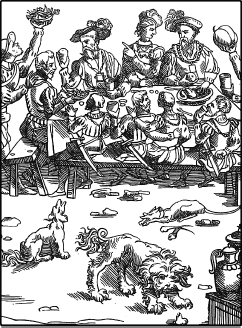

Social hierarchy and rights of precedence were manifested scenically in the banquet hall and in the arrangement of the tables mounted on trestles that could be set up or removed as needed. Generally kept separated, the tables could be placed side by side to group guests of the same rank and social equality, according to precise convivial logistics. Even in monastic customs, the most decidedly “democratic” in imposing an egalitarian dimension on the refectory, the abbot eats at a separate table in the company of occasional guests who are only provisionally allowed to be part of the group.17 Around each table, the assignment of places took on significance based on the greater or lesser proximity to the head of table (meaning the man in power), represented through theatrical staging: the elongated rectangular shape of the table, as seen in the iconography, characteristic of the medieval table, lent itself well to designating the central position of the dominus (or the special guest) at the center of the long side. We know, for example, about the ceremonial complexity at the court of Byzantium that ruled over placement at the table, determined by the position and prestige of the individual.18 And we know about the resentment of Liutprando, bishop of Cremona and ambassador of Emperor Otto I, on seeing himself seated at the fifteenth position, much too far (in his view) from the sovereign.19

Dante Alighieri apparently had an experience of this kind when he went to Naples to see King Uberto, as Giovanni Sercambi relates in one of his novellas. The king, eager to have the famous poet as his guest so as “to see and hear his good judgment and brilliance,” invited him to court. When Dante arrived, he was “dressed in the most ordinary clothes, as only a poet can.” It was precisely the hour of dinner, “and having washed their hands and gone to the table, the king and the other barons took their seats, and Dante was finally placed at the end of the table,” which is to say the seat farthest from the king. Offended by such mistreatment (although the king, seeing his grubbiness, never imagined it could be Dante), the poet ate his portion and “immediately left … to return to Tuscany.” The king, after some time at the table, asked for Dante and wanted to know why he had not presented himself; he was told it was that grubby individual at the end of the table who had already left in haste.

Distressed by the confusion, the king sent a servant after him; finding Dante not far off, the servant handed him a letter of excuse. Turning around, Dante returned to Naples, but this time he presented himself to the king “dressed in a splendid robe.” Uberto “at dinner had him placed at the head of the first table, right beside him.” As the food and wine began to arrive, the poet astounded the noble company with his bizarre behavior. “Taking the meat, he rubbed it all over his clothes, and the wine as well. ‘That one must be a ruffian,’ commented the king and the barons, seeing him pour wine and broth on his clothes. The king said to Dante, ‘What is it that I have seen you do? For someone presumed to be so wise, how could you do such ugly things?’” Dante’s reply, at this point foreseeable, was a severe moral admonishment: “Your majesty, I am cognizant of this great honor that you bestowed, but you bestowed it on my clothes. I therefore wanted them to enjoy the dishes that were served.” There was general embarrassment, but the king recognized the supreme honesty and sagacity of the poet “and honoring him, made him remain at court so as to hear more from him.”20

Even serving dishes contributed to expressing prestige and power: utensils and dishes of great value distinguished the royal and princely table from the common one. Not wood or pewter or earthenware (the last being the most widely used material at that time for table service21) but gold and silver were displayed on lordly tables, along with precious glass and crystal. The idea was to impress the guest, overwhelm him, subjugate him with the host’s wealth. The banquets of Roger II “inspire admiration in the other princes”22 (a noteworthy pairing of two seemingly incongruous terms: an “admiration” that is “inspired,” like awe or fear). In fact, those who reclined at the table (the term discumbere, used here by the chronicler, seems to indicate the retention, still in the twelfth century at least in the kingdom of Sicily, of the Roman custom of reclining while eating, generally abandoned in the early centuries of the Middle Ages) were astonished by the abundance and variety of foods and beverages and by the “incredible opulence of the service”: everyone was served in “cups or plates of gold and silver”; even the servants were luxuriously dressed in pure silk.

The mania of ostentation could extend to the kitchen as well. Roger of Wendover wrote that Empress Isabella (sister of Henry III of England, third wife of Frederick II of Sweden) had not only goblets for wine and plates of purest gold and silver but also—and this is what was most shocking, excessive, and to say the least, superfluous—cooking utensils made of precious materials: “all the pots, large and small, were made of purest silver.”23

Even at the most sumptuous of tables, wine cups and eating utensils were never intended to be used by only one person but by at least two at the same time. Cups were passed from hand to hand;24 bowls (for liquid foods) and cutting boards (for solid foods) were placed between two guests. None of this can be interpreted as a shortage of utensils in view of the fact that this was common to the tables of both the very rich and the very poor. Rather, we may discern in this once again the expression of the sense of community (sharing food as a means of and a metaphor for living together) that deeply permeated medieval culture. This indisputable fact gave rise to so many comic episodes in the fiction of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, in which the seating side by side of incompatible guests, of differing behavior at the table (different speeds of consumption, different abilities to swallow hot foods), led to occasions of unwelcome fasting for the less vigorous and audacious.25

There were, however, rules of etiquette that imposed a certain uniformity on dining behavior. European literature, especially at the start of the thirteenth century, produced numerous manuals of “good manners” that instructed gentlemen (and ladies) and their offspring how to behave at the table.26 One should not wipe one’s hands on one’s clothes but on the tablecloth (napkins having yet to be invented); one should wipe one’s mouth before drinking (also out of respect for the dining companion who drinks out of the same receptacle); one should not slurp from the plate, not bite into bread and then put it back in the basket, not put one’s fingers into sauces, not spit or pick one’s nose, and not clean one’s teeth with the point of a knife—these and other rules came to be set down and codified for the primary reason of raising a boundary, fencing in a protected area of privilege and power by distinguishing its usages from those “outside” of it. And those “outside” meant peasants, the “rustics” who precisely then, from the thirteenth century on, began to be considered and designated as the negative pole of an urban or aristocratic society that became increasingly more rigid about its privileges and separateness.27

“Good manners” (urbane and courtly) were the formal means of this process of enclosure, and the table, once again, serves as the locus of identity and exclusion. The increasing formality of the convivial ritual did not, however, eliminate the physical, material dimension of the relationship with food typical of medieval sensibility. An example is the diffidence toward the fork, seen only exceptionally on the tables of the period; the hands were long preferred, thereby assuring a direct, tactile contact with food.28 In this instance the books of good manners limit themselves to suggesting the use of only three fingers, not the whole hand, “as peasants are wont to do.”29

During the high Middle Ages, rules of dining behavior were established within the monastic society for the purpose, here, too, of defining and marking its own identity and a lifestyle different from that of “others.” Particularly important is the Benedictine vow of silence,30 to be practiced at all times in daily life and thus also during meals. This would seem unnatural for a place (the table) that is geared by its very nature to discussion and communication. But it is precisely this that reveals the will to remove oneself from the world and its logic, to remain outside the noise of the worldly banquet31 so as to establish another kind of communication, with God and with the divine teaching that one receives from the readings during meals. Not to speak, but to listen—this is a model of behavior that even a man as powerful as Charlemagne imitated, according to his biographer Eginardo,32 having Augustine’s City of God read to him at the table (at other times, it would seem he preferred the deeds of legendary heroes, such as those of King Arthur,33 which he is said to have loved). As for the monks, it is amazing to see how the rule of silence led to the invention and codification of a gestural language entrusted to the hands, the tongue, the eyes, and to some degree, the whole body to describe and indicate (while respecting the rule) all the foods and dishes that appeared on the table and could become a subject of discussion. This we learn from the consuetudini of the abbey at Cluny dating from the eleventh and twelfth centuries.34

Even the quality and forms of food provided the motivation for communicating during meals. If the monastic diet can be characterized primarily by its renunciation of meat (for the most part), the substitute foods—vegetables, cheese, eggs, and above all, fish—became its symbol. To eat fish or in any case to give up meat during Lent and fast days was not so much a gastronomic humiliation (there is ample documentation on the opulent banquets built around fish that were enjoyed by the ecclesiastic hierarchy throughout the Middle Ages) as it was a sign of identification with a very specific religious community. The practice of fasting (in the technical sense that medieval precepts gave to the term, meaning to eat once during the day, after sunset) was imposed on everybody during certain liturgical celebrations and on the monks during extended periods of the year as well. “Witnesses affirm that he did not fast when the king was fasting”—this explains how, according to an Arab chronicle of the twelfth century, it was possible to recognize that the emir of Palermo, Filippo di Mahdia, “was really a Muslim” and why the Norman King Roger II had him condemned to the stake.35

Beyond these very general images, it was the nature and quality of individual foods that determined the social identity of the person who consumed and offered them. Durable foods (dried meat and fish, cheese, and products like grains, legumes, or chestnuts that can last throughout the year) necessarily had a “poor” image that evoked the problem of survival. Fresh foods (meat, fish, and fruit) suggested instead images of luxury. Another important differentiating element was seasonal food and local food (the great myth of present-day culture), which the Middle Ages tended instead to devalue, seeing them as a mark of poverty or, at the very least, of mediocre normalcy. While ordering for his sovereign the best products of every region, Cassiodoro, minister of Theodoric, king of the Ostrogoths, observes in a letter that “the opulence of the royal table is of not inconsiderable importance to the State since it is thought that the master of the house is only as wealthy as the rare dishes on which one dines at his table. Only the common subject is satisfied with what the territory provides. The table of a prince must offer all kinds of things and arouse amazement merely to look at it.”36

The ability to bring together on one’s own table foods from various sources was therefore an important indication of wealth and power. Noteworthy is a passage from John of Salisbury, who condemned the excessive ostentation of the tables of his time (with quotations from Macrobius and ancient anecdotes), in which he described a visit he made to Puglia—probably between 1144 and 1156 in the retinue of Pope Adrian IV—and a dinner to which he was invited by someone identified only as “a rich man from Canosa.” He apparently kept his guests at the table from three in the afternoon until six the next morning, drowning them in foods from every part of the Mediterranean: “delicacies from Constantinople, from Babylon, Alexandria, Palestine, Tripolitania, from Berber regions, Syria, Phoenicia”—as though (John remarks) Sicily, Calabrua, Puglia, and Campania were not enough to enlighten a “sensitive guest.”37

It was not only through the substance of food that the language of power and wealth was transmitted. Equally important were the forms in which it was presented, the “gastronomic architecture” that constituted the inevitable complement of convivial architecture. However, the medieval period was not yet the era of the dazzling scenic inventions, of the astounding creations that amazed the guests of princely courts38 between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, transferring to the realm of spectacle a large part of the convivial experience, alternating between visual illusions and gustatory deceptions. Nevertheless, here, too, there was no lack of attention to the forms and theatricality of the food. One need only recall the “armed castrato,” a large ram or billy goat slowly cooked on a spit and then “decorated” with sausages woven around the horns before being served “on a great table.” This is a recipe from a fifteenth-century cookbook, compiled in southern Italy.39

The special attention given to color in the preparation of dishes is made clear in these texts. Also noteworthy is how the chromatic concerns of medieval cooking, unlike those of today, developed autonomously in the art of flavors. If the color of a food is understood today to be a proof of its freshness and its “nature,” in the Middle Ages, on the contrary, the food was “colored” with foreign substances to give it an artificial and almost unnatural appearance. Various ingredients (above all, herbs and spices) were used to color foods, and many sauces that accompanied meat dishes were known by their color: white sauce, camelline sauce (from its characteristic camel color), green sauce, black pepper sauce, and many others, for which the cookbooks offer numerous recipes.40

Directions are often quite explicit: “color with the yolk of an egg” in the recipe for a meat pasty;41 “color with saffron [colora del safferano]” in the recipe for the broth known as “martino”;42 “color with saffron [colora de zaffarno]” in the recipe for a pasty of lamprey;43 “color with saffron” for a pasty of shrimp;44 and for an herb pie, “give it color and as much saffron as you can [dalli colore et çaffarano al meio che poy].”45 The taste for yellow (achieved by extensive use of egg yolk and saffron and by techniques of frying and browning) made a clamorous return in the cookbook of Maestro Martino, which speaks of “coloring” yellow a great many dishes46 and constitutes a distinguished treatise on medieval gastronomy, a kind of gastronomic companion piece to the golden backgrounds so typical of the painting of that period. The origin of this kind of predilection was the solar image of gold, symbol of an indestructible eternity,47 an image that was normally realized by alternative products because gold, even more than inedible, was unattainable by most. In fact, real gold was used at times in the preparation of food, and we know how the search for that “potable gold” was central to the work of alchemists.48 Still today there are cooks who like to adorn their dishes with gold leaf (risotto alla milanese topped with a leaf of gold is one of the history-making dishes of Gualtiero Marchesi, the most famous Italian chef of the twentieth century).

Along with yellow, there was also much use of white, symbol of purity,49 particularly indicated for Lenten foods. To some degree, all colors appeared on the table in a multicolored play about which I would like to offer a final example, the tricolored Lenten pie made of almonds, ground and boiled, divided into three parts; mint, parsley, and marjoram (accounting for green) are added to the first part, saffron to the second, and white sugar to the third.50 Among the colors most common to us today, the rarest on the medieval table was assuredly red, which finally gained recognition because of the popularity of tomato sauce—but not before the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.51

Manners of cooking and preparation also contributed to accenting this “unnatural” character of medieval cuisine, against which the moralists railed, invoking frugality and simplicity. John of Salisbury, mentioned earlier, deplored the custom of stuffing the meat of one animal with the meat of another so as to render it unrecognizable by the smell—a technique, John reminds us, already in use in the Roman era with the porcus troianus (meaning a pig stuffed with other meats, recalling the Trojan horse). But at least, he remarks, at the time of the Romans, people were amazed by such inventions, served only exceptionally, whereas today they seem to have become the norm and no one is surprised by them any longer: “many things that no longer amaze us, because they have been used and abused, aroused admiration and astonishment in our ancestors: the Trojan pig, today domesticated.”52

In conclusion, the decisive moment in the convivial framework for defining and representing the structures of power is the division and distribution of food. As is known, both the Celtic-Germanic tradition and the Greco-Roman tradition attributed fundamental importance to the portioning of meat.53 The quality of the cuts assigned to guests (the appreciation and rules varying with the culture) served to recognize the hierarchy between individual guests, whether confirming it, destabilizing it, or overturning it. The acquisition of the “best piece” was often at the heart of furious contests of power, regularly acted out in the banquet hall with a more than evident symbolic and metaphoric finality.54 No less important (especially in Celtic and Germanic traditions) was the quantitative aspect of the challenge: power fell to the one who could eat the most, the one who, by ingurgitating enormous quantities of food, succeeded in demonstrating his purely physical and animal superiority over his peers.55

Medieval culture is deeply ingrained with this tradition. The image of the powerful one who eats a lot (who eats a lot because he is powerful and is powerful because he eats a lot) permeates the literature and is also seen, in contrast, in the obsessive insistence of monastic views on the need to humble oneself by moderating the appetite. In the high Middle Ages, the primordial image of the powerful man as one who eats and drinks more than others, thereby demonstrating his strength and legitimizing his position of power, appears to have been extremely vivid and active. An example is the episode of Guido, duke of Spoleto, who, according to Liutprando of Cremona, was rejected as king of the Franks because it was discovered that he ate little.56 In this perpetuation of the anthropological significance of food as a sign of power in a society dominated by the fear of hunger, important modifications took place over the course of time.

Later, the quantitative aspects of consumption in this “dietetics of power” partially disappeared (although present in chivalric literature), increasingly replaced by a qualitative character: how to select food, distinguishing between refined food and rustic food, seems to have been an essential part of noble behavior as it developed in courtly ethics.57 Exquisite wines and pure white bread, delicate meats and perfumed Oriental spices58 created a new idea of luxury, no longer determined by the priority of quantity. Quite the contrary, we come across a figure like that of Frederick II, who, to maintain his health, ate abstemiously and only once a day. And it should be mentioned, to emphasize the irreligious character of the emperor, that he did this for his body, not his soul: “not for divine reward but to preserve his physical health,” as pointed out by Johann von Winterthur.59 No one would have written anything like that about Charlemagne. A prisoner of the social customs and obligations of his culture, Charlemagne would never have allowed himself to be concerned about his health; though suffering from gout, he continued to load his table with enormous quantities of spit-roasted meats.60

The concept of heavy eating did not disappear entirely. Let us say that with the passage of time it changed meaning, placing itself more on the level of potentiality than of reality. No longer a matter of enormous consumption, the new way of showing off power in noble society during the early and high Middle Ages was to provide a great variety of food on one’s own table, lavishly offered to the largest possible number of guests. We might say, paraphrasing Bloch, that the progressive transformation of the ruling class from a de facto nobility to a de jure nobility61 found its perfect correlative in eating styles: even heavy (and good) eating transformed itself in a way from a de facto reality into a de jure reality. The concept thus underwent a change: a man of power was not someone who eats a lot (who can and must eat a lot) but someone who has the right to eat a lot—that is, to have many kinds of food at his disposal. At that point, the question of the right to eat—more immutable and inviolable as the nobility became closed within itself and stood on its own privilege—may no longer have corresponded to reality. A lord in the late Middle Ages was no longer necessarily a great eater but more than anything a great director who manifested his power in convivial spectacles during which food was indeed eaten—but most of all looked at.62

The right to eat (which replaced the obligation to eat) in the society of the late Middle Ages was expressed in forms increasingly stereotyped and ritualistic. The Ordinacions of Peter IV of Aragon (1344) prescribed that each guest at the table of the king be served in keeping with his status: “since in serving it is proper that certain persons be honored above others in accordance with the level of their status, we want that in our platter there be enough food for eight; food for six will be placed in the platter for the royal princes, archbishops, and bishops; food for four, in the platters of other prelates and knights who sit at the king’s table.”63 In the nineteenth century, at the Bourbon court of Naples, a similar dining code was still observed: during the reign of Ferdinand IV, the king could have ten courses, the queen six, and the princes four.64

At the beginning of the fourteenth century, the progressive rigor of standards of consumption as the status symbol of noble privilege found expression in “sumptuary” laws, aimed at defining alimentary and dining models of the different social classes and confining them within a predetermined scheme.65 The prohibition against exceeding certain limitations on the number of guests, courses, and dishes was always justified by such moral motivations as the condemnation of waste and the recommendation of moderation in consumption. What nonetheless remained substantive was the desire to normalize lifestyles, to prevent behavior unsuited to the “obligations” of one’s social status and disrespectful of hierarchies. For this, above all, excessive manifestations of wealth and of power centered on food and dress were condemned and prohibited.

For example, the Ordinationes generales et speciales, proclaimed in 1308 in Messina by Frederick III, prohibited public banqueting (generalia convivia) for weddings—that is, transforming a perfectly legitimate celebration into a pretext for forging agreements and alliances in the midst of a family event. During the period of a wedding, Frederick decreed, one could organize a banquet to last only one day, exclusively for first- and second-generation relatives of the bridal couple and for those who came from distant places.66 Another law prohibited all functionaries and local representatives of the monarchy (“counts, barons, soldiers, squires”) from entertaining guests “from outside the territory of their residence,” which would indicate their intention to enlarge their own legitimate sphere of influence. In addition, the cost of a banquet could not exceed one-third of their daily budget.67

Restrictive laws of this kind reveal the tendency on the part of the ruling classes to construct and consolidate relations of fealty and alliance around festive tables, in accordance with an anthropological model that surely recalls the primordial image of the leader who, after having accumulated loot and riches, redistributes them to his men, thereby legitimizing the power invested in him. The same principle of redistribution, transposed by Christian culture into a moral and religious key, reappears in the exhortation to the rich and powerful to practice charity, a genuine social obligation expressed first and foremost in the form of meals and food offered to the poor, immediately perceptible in its symbolic significance.68 To feed the pauperes (in the dual medieval sense of “weak” and “indigent” and with all the ambiguity possible in a culture that identified as “professionally poor” a large segment of the ecclesiastic and monastic corps) was a duty that no person of power could neglect. Moreover, it assured the salvation of the soul, and from that point of view, the needy were the best possible medium for establishing a cordial relationship with heaven. This accounts for the provisions, in the life or death of testators, to feed a certain number of poor people at a given festivity or anniversary; the richer and more powerful the donor, the more generous he was obliged to be. A chronicler relates that in 1233 Frederick II magnificently celebrated his own birthday in the public square of San Germano: “more than five hundred poor people ate and were well sated with bread, wine, and meat.”69

In connection with the idea of the poor as a possible key to heaven., we must look at ethnographic and anthropological studies, focused on southern Italy, that set apart the figure of the poor person (a weak link and marginal factor in the social order) as the “vicar of the dead,” meaning the image and counter-image of the dead, and thus a means of making contact with their world.70 From this, it would be easy to arrive at the theme of the funeral banquet, the meal to honor the dead, perhaps even set up at their tomb as a means of communicating with them and as the symbolic representation of the uninterrupted solidarity and identity of the group.71

Even in the case of charity to the poor, the fundamental notion of food as a mark of social and economic identity remained operative. In the already cited Ordinacions, Peter of Aragon states that all leftovers should be given to the poor. “Whenever wine spoils in our cellar … the cellarer diligently offers it to our alms.”72 And again, “when bread in our bakery happens to go bad … the baker makes a point of solicitously getting it to our charity,” along with bread left over from dinner.73 Also, “every time fruit and cheese go bad they are immediately distributed to the almoners.”74 Moreover, the Rule of the Camaldoli monks had already established that spoiled, acidy, or moldy wine was not to be served in the refectory but should go to outsiders: to the poor and pilgrims stopping by.75

The “poor” thus also had a place, and one of primary importance, in this game of abundance and ostentation—not only because they themselves were the means and the object but also because their poverty (a social and economic situation that was so widespread it could be called “normal”) constituted the only true motive for which a rich and generous table could be the site and symbol of privilege and power. The system was structurally integrated in its contrasting elements: only a situation of widespread hunger (or precarious conditions of life) could justify so intense and so deep a symbology of food. The “poor” themselves shared the culture of abundance and ostentation: that is, the real poor, not those who, having made a profession of poverty, could allow themselves to sublimate values and to choose renunciation, abstinence, and hunger as the ideal model of life. The real poor—whose alimentary style so many monks and hermits and bards of joyful poverty pretended to re-create for themselves—aspired instead to fill their bellies, and as copiously as possible, conforming in every way to the model of the way the powerful ate.

Only for the latter was abundance a daily practice; for the poor it was a dream, an exceptional event. The Land of Cockaigne, that great popular myth of full bellies and sated appetites that spread throughout Italy and all of Europe in the early twelfth century,76 was the utopian obverse of a frustrated wish, the mirage of an oasis to which only a few were allowed access, whereas most were excluded. The poor also shared the culture of abundance, elevating it to their favorite dream and in some cases translating it into reality when certain recurring rituals (Christmas, Easter, the feast of a patron saint, a family wedding) imposed on the celebration the plenty and ostentation that characterized the daily banquets of princes. In medieval culture it was indeed the abundance of food that distinguished a holiday, as though it were a propitiatory gesture to exorcize the fear of hunger (but the subject has a broader and more general meaning).

The same ecclesiastic culture (which for a long time regarded the food miracle—or more precisely, the proliferation of food—as one of the important signs of sainthood) saw in the festive banquet a logical and symbolic priority that took precedence over any other form of celebration. Most of the gifts of food or meals offered to monasteries and churches were on the occasions of major religious holidays. Monastic laws and ecclesiastic precepts rigorously forbade practices of fasting or abstinence on feast days,77 and there is no room for doubt about this. When Christmas happened to fall on a Friday, the disciples of Saint Francis (as related by Tommaso da Celano in the second biography of the saint) heatedly discussed among themselves whether to give precedence to the obligation of abstaining from meat and of moderate eating on Fridays or to the obligation of celebrating the recurring holiday of Christmas with a generous banquet. In their uncertainty, they turned to their master and sent Brother Morico to ask the question. “You are sinning, brother,” was the brusque reply of Francis, “to call the day the Child was born for us [a day of abstinence]. On a day like that I would like even the walls to eat meat, but since that is not possible, let them at least be spread with it.” Francis, the biographer continues, “wanted poor people and beggars to be fed to satiety by the rich, and oxen and donkeys to be given a more generous portion of food and hay than usual.” And once, it seems, he said to his companions, “If I could speak to the emperor I would beg him to decree by a general edict that all who have the means should scatter wheat and grain on the streets so that on a day of such celebration the birds, and particularly our sister larks, have food in abundance.”78 The particular devotion that Francis felt for Christmas made him want to set a great banquet in which all men, rich and poor, could take part along with the animals, the birds in the air, and the walls of the houses, were it possible.