Chapter Thirty

She had been thinking about the story for days, ever since the pieces began coming together, and finally decided to write it in as straightforward a way as possible. The facts of the story were sensational enough. She didn’t need to embellish them with the writing.

EMMA LAZARUS MURDERED, EVIDENCE SHOWS

Death Attributed to Cancer Was Due to Poison

By Nellie Bly

The World has learned that the death of Emma Lazarus, the revered poet and social reformer, was caused by arsenic poisoning rather than a cancer, as originally believed, and that the person who administered the poison was Miss Lazarus’s editor at the Century Magazine, Richard Gilder.

A highly respected physician and chemist utilized by the World has examined samples of Miss Lazarus’s clothing and handwritten letters, which have revealed the presence of fatal levels of arsenic in her system in the weeks immediately prior to her death. Although arsenic can be useful in the early stages of cancer, all of the doctors providing care for Miss Lazarus had ordered arsenic treatments stopped six months before her death. Yet according to our physician’s tests, the arsenic levels in Miss Lazarus continued to rise until her demise.

Further investigation by the World revealed that arsenic was given to Miss Lazarus almost daily and without her knowledge by Mr. Gilder, her longtime editor at Scribner’s and the Century. The two met every afternoon during the last three months of her life to catalogue her writings before her death. It was during those meetings that Mr. Gilder administered the poison to Miss Lazarus through a coffee cup. The World has obtained the mug in question and turned it over to the New York City Police Department.

When questioned by a World reporter, Mr. Gilder acknowledged making coffee for Miss Lazarus daily and providing the cup to her that contained the arsenic. According to the staff at the Lazarus home, no one besides Miss Lazarus ever drank from the cup, and no one besides Mr. Gilder ever poured coffee into it.

The apparent motive for the murder, revealed in a conversation with a World reporter, was Mr. Gilder’s jealousy over the infatuation of his wife, Helena, with Miss Lazarus. As Miss Lazarus’s medical condition became graver, Mrs. Gilder became increasingly pronounced in her feelings for Miss Lazarus, and Mr. Gilder became determined to put a stop to it.

Miss Lazarus was expected to survive no more than six months following her diagnosis of cancer. The poison, according to the physician, shortened that already limited time by three months.

Nellie chose to steer clear of any mention of Hilton and the land theft of Montauk Point. It would simply confuse matters, and in the end had nothing to do with Emma’s poisoning. Of course, Hilton would learn that he had lavished Charles DeKay with undue rewards, and Charles would suffer as a result. But that was fine with Nellie. After all his duplicity, it was richly deserved.

As she read over the story before handing it to Cockerill, Nellie did not feel the satisfaction of a reporter finally completing a story after months of digging for the truth. All she felt was a profound sadness for Emma. Her closest friends had betrayed her, one had even killed her. Emma had died without knowing real love. It was such a pity, a woman who had given so much to others. No doubt she had tried for love, with Helena and possibly with Charles, but they were unworthy of her and violated her trust at every turn. But Emma was not alone. In the confined arrangements of the day, a spirit as free and strong as hers could almost never find fulfillment. She obviously yearned for it—that was the message of her last poem—but it was denied her to the end. For all Emma had done, for all the people she had helped and wrongs she had attempted to set right, the one thing her heart craved most would never be hers.

Unlike Emma, Nellie had found a love, but she had failed to embrace it. She lacked Emma’s courage. Nellie had been too frightened, too hardened, to accept love. She had rebuffed Ingram at every turn, yet he had shown a patience with her she found nothing short of remarkable. Had he treated her the same way, she would have left him long ago.

All her life she had closed herself to love. There had been so many shattering moments that she had lost the capacity to trust anyone, male or female, friend or lover. She was fond of Ingram and she enjoyed their lovemaking, but there was a part of her that always held back, though one could never ask for a better, more devoted companion. What Emma would have given for an Ingram in her life!

She suddenly was ashamed of herself and felt the urge to hurry to his house, run into his arms, and declare that she’d been a fool. She would ask for his forgiveness and tell him she’d been so hurt that she could no longer trust her heart. More than that, she hadn’t allowed any room in her heart. The daily struggle to find work and support herself and her mother and her sisters had overwhelmed her. Between the bad memories of her childhood and her solitary struggle to survive every day, she had given up on love. But Emma had convinced her to open her heart, to realize at last that nothing was more important than love. That was the message of the last poem. And Emma was right. She saw that now. She walked over to Cockerill’s desk without bothering to read over the story, handed it to him, and said she was going home.

Nellie’s excitement only grew on the streetcar ride to Ingram’s house. She spent the entire time planning her life together with him. Ingram’s work would take him to Prague and Vienna for a year or two. Nellie would use the asylum story and the Emma story to convince Pulitzer to let her report stories from Europe. No other paper had a reporter based abroad, and many New Yorkers, especially World readers, were interested in news from their former country. As an American, Nellie would be the eyes and ears of the reader. It was an excellent idea, she decided, one Pulitzer could not resist. She would have to figure out what to do with her mother, but if Pulitzer agreed, Nellie would have enough money so that her sister would no longer need to work and could look after her.

All the plans left her as giddy as a schoolgirl. She hadn’t felt this way since before her father died. That was why she was so unprepared for what awaited her when she stepped off the streetcar.

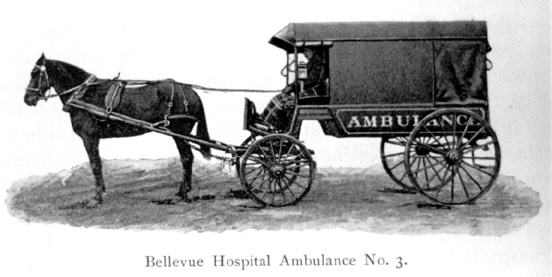

The first thing she noticed was the ambulance. Ingram kept it in the rear of the house for emergencies. It was essentially a large wooden box with a white canvas on top and a five-foot-high door and painted red cross on the side, set on the axles of a horse-drawn carriage. A crowd of gawkers had gathered around it, and two policemen were trying to clear them away. Mrs. Fairley, standing by the ambulance, had a large red welt on her forehead and was sobbing uncontrollably. Nellie’s first thought was for Mary Jane, but she saw her mother wandering on the outside of the crowd, looking disoriented. Near the front entrance the security guard Ingram had hired sat against the brownstones, holding a blood-soaked bandage to his head. Suddenly two other policemen emerged from the front door and hurriedly carried a man on a plank toward the ambulance. Nellie peered closely to make sure because she didn’t believe her eyes. The man lying unconscious on the plank was Ingram.

She raced toward Mrs. Fairley and pushed her way through the crowd. “Mrs. Fairley. What happened?”

The older woman tried to hold back the tears but was overcome with emotion.

“Please. Mrs. Fairley. Tell me what happened.”

Mrs. Fairley nodded and forced herself to speak. “Some men started rummaging through the house, asking about a cup. The doctor tried to stop them and suddenly he grabbed his chest and collapsed. They got scared and ran off. I ran outside and screamed for help—”

She looked over at Ingram on the plank and started sobbing again.

“Is he breathing?” pressed Nellie.

“I don’t know. The policeman told someone to get an ambulance, and I said the doctor had one here. They’re taking him to St. Mark’s hospital.”

The rubella, she thought to herself. Ingram always said it would kill him. But she never believed him.

Over the policeman’s protests, Nellie insisted on climbing into the ambulance and making the twenty-minute ride to the hospital with them. She clutched Ingram’s hand and whispered to him, in between shouting at the ambulance driver to hurry.

“I’m here, Ingram. I’m here. I love you. Please know that. I love you … Hurry! He’s barely breathing!!” she shouted to the driver.

Nellie wanted Ingram to get to the hospital as fast as possible. But the fastest route was over cobblestone roads, with multiple turns that shifted the ambulance carriage from side to side and nearly turned it over. The jostling, she knew, was killing Ingram. Racing through Chelsea, she could feel the life slipping out of him.

“Ingram. Don’t leave me! Please don’t leave me! We have so much to do together. We have so many plans to make—”

His breathing was becoming so weak, she could hardly hear it.

“Ingram! I will go to Europe with you. I will go anywhere with you. Breathe, Ingram. Please. Breathe—”

But his breathing had stopped. And she knew, as they were tossed back and forth in the ambulance bouncing over the cobblestones, that it would never resume. She kissed his hand and began to cry, as helpless as she had ever felt in her life.