Chapter Eighteen

On the ferry ride to Long Island, Nellie read Emma’s final letters to Julia. The steady hand of the manuscripts at the Lazarus home was now shaky and weak. All the spirit and strength had been sapped. The last letter was particularly heartbreaking:

My Most Dear Mrs. H.:

Please excuse my brevity. I lack the strength to convey all that is in my heart, and for that I shall never forgive myself. I so appreciated your recent visit. Your kind smile and even kinder eyes eased my discomfort beyond description. You have always provided such joy and inspiration.

Though I sadly fall short of your example, know that I shall always remain, Your faithful servant,

Emma L.

A wizened older woman with chestnut skin, pencil-thin wrists, and weather-beaten features had met Nellie at the ferry in Sag Harbor, the main fishing village on eastern Long Island. Though her clothes were tattered and her belly protruded from malnutrition, Maria Pharaoh had a royal dignity about her, with an erect posture and direct gaze. Nellie offered to treat her to a meal or some cider in a whaling inn, but Maria did not want to spend their time searching for a place that would allow her inside. Her guess was there would be none. Instead they sat on a wooden bench by the dock on a chilly fall day and even so drew sullen stares from the white fishermen.

Maria waited silently while Nellie read through a packet of newspaper clippings Emma Lazarus had compiled for Maria to show to receptive strangers. The shameful history of Maria’s people was set out in black and white.

Unlike the American West, where the natives congregated in distinct tribes, the Indians of New England and Long Island shared a similar language and culture. Europeans assigned them names based on the Indian names of where they lived—Shinnecock, Pachogue—but the major differences among the native groups were mainly of dialect and accent. The most important of these tribes, the Montauks (as the white men called them), lived on the easternmost part of the southern fork of Long Island. The medium of exchange among the Indians of New England, and then among the Indians and the white settlers in the early Colonial era, was the wampum, and there was more wampum on eastern Long Island than anywhere else in the colonies. The Montauks were the keepers of the wampum as economic high priests for the natives in the northeast, and as such they enjoyed a noble place among the natives—and a targeted position among the whites. In a remarkably short period of time, the whites managed to steal Montauk land and take possession of the Native American currency.

By the early 1880s, they had succeeded. In 1871, a New York state court referee ruled that the Montauks had no property rights that white men were obligated to respect. In affirming the referee’s decision a few months later, the New York Supreme Court held that the Montauks were “trespassing” on their own land. To mute any public outcry, the Montauks were then placed on a reservation—predictably located on the least inviting parts of eastern Long Island. But soon that, too, became valuable property for railroad owners, fishermen, and white land developers. In October 1879, a man named Arthur Benson petitioned the New York state court to sell him the reservation land at “auction,” and for $150,000, Benson was awarded the entire parcel.

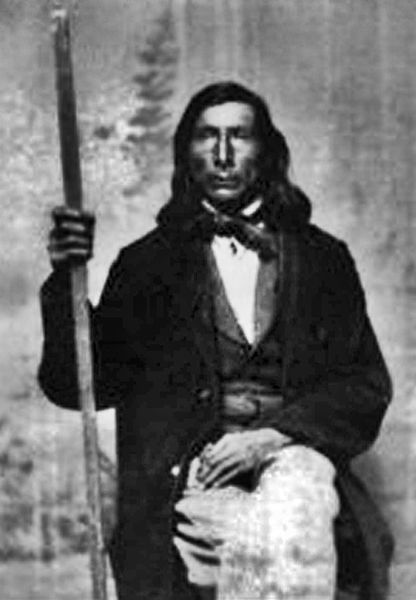

Maria took up the narrative from there. “After they stole our land and placed us on the reservation, my nephew David came forward to lead us. He had worked for the Union Army and observed the white man’s ways, and he understood them as a child understands a pet. He knew the whites would ignore him if the tribe referred to him merely as their leader, so he asked them to make him king. He did not know exactly what it meant to be king, only that the whites treated you differently if that was what you were called. The newspapers wrote about him as king, and with this title he went to Albany to ask the government of New York to give us back our land. David had served with some of the men there in the cavalry, and they offered to help him. But Mr. Hilton would not allow it.”

Nellie perked up. “Mr. Hilton? Henry Hilton?”

“Yes.”

“How was he involved?”

“Mr. Benson had sold much of the land to Mr. Hilton—”

“And Mr. Corbin?”

“Yes. To Hilton and Corbin.”

“Go on. Please.” Nellie could sense the pieces about to fall into place.

“The men in Albany became afraid to help David, even though he had saved their lives, and would no longer speak with him. Some said it was because our tribe now had African blood because they hated the Africans, and this allowed them to say our blood was no longer pure, though of course that was a lie. David found a lawyer, another soldier he had fought beside, to tell a judge about all the stealing, but then something terrible happened.”

The older woman, stolid in recounting all the injustice, paused to gather herself. “My sister, David’s mother, was murdered in her home. David found her.”

The old woman handed Nellie a tattered clip from The Brooklyn Eagle. “The back of her head was crushed in.”

Nellie read the clip.

Aurelia Pharaoh, mother of King David Pharaoh of the Montauk tribe of Indians, was found dead on the floor of her cabin. Foul play was suspected, but the jury settled that by a verdict she had died from “a visitation of Almighty God.”

“They thought that would be the end of it. David would be so upset and frightened that he would stop his efforts to regain our land. But David was not afraid. He was devoted to his people. He suffered from the loss of my sister, yes, but that only made him stronger. And so they murdered him, too.”

The old woman handed Nellie another clip from The Brooklyn Eagle, frayed and browning around the edges like the first one.

David Pharaoh, the King of the Montauk Indians, is missing, under suspicious circumstances. His hat was found on the deck of a schooner, and as he was known to have a large amount of money, foul play is suspected. He is the last of the Montauk tribe.

“And so they killed them both, Aurelia and David. My sister and my nephew.”

Nellie felt terrible for the old woman. There was not a doubt in Nellie’s mind that she was telling the truth.

“But he was not the last of the Montauks,” said Nellie.

“No.”

“And after they killed him, you went to see Miss Lazarus.”

“Yes. Some people from a faraway land, who had crossed the great ocean, settled near here. They told me she had found them food and shelter and a place to live. They said her heart was good. And so I went to see her at the docks in Manhattan, where those who cross the ocean walk onto the land.”

“What did she say?”

“She said she would help me. She wanted me to meet a lawyer. I said I had no money for a lawyer, but she told me not to worry, that she would pay the lawyer.”

“Did you tell Miss Lazarus about Hilton’s involvement? And Corbin’s?”

“Yes. She was not surprised. She said they were bad men. But she would try to stop them. She said she had beaten them before and would have ways to do it again.”

“Then what happened?”

“Miss Lazarus crossed the ocean.”

“And the lawyer?”

“He watched the grass grow by the cobblestones near his office.”

Nellie had to smile.

“So he did nothing unless Miss Lazarus was around?”

“Nothing.”

“And when she returned?”

“She was weak from the cancer, but she became very angry with him. And he did bring some papers to the court, asking for the return of our land. She still held hope and would write to me. But soon she lost all strength. And then she died.”

“And the lawyer?”

“He said he could no longer work on the case.”

“But she had paid him.”

“Yes. But he wanted nothing more to do with me.”

Something wasn’t making sense to Nellie. “Miss Pharaoh, do you know why Hilton and Corbin were so determined to keep your tribe away from Montauk?”

To the old woman it was obvious. “They want our land.”

“Yes, but why? Corbin already has the sole railroad to Sag Harbor. No one else could build one farther east without connecting to his. If they tried to build their own, it would be prohibitively expensive.”

“There are many things I do not understand about white men. Their greed, their violence. They stole our land and moved us to a reservation with great praise for their own kindness, then took that land for themselves as well. When we protested, they killed my sister and my nephew. What can there be to understand about people such as this?”