Chapter Four

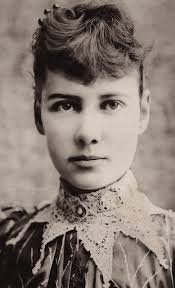

Nellie was not always so restrained with men. After being thrown out of their home when she was eight and then growing up in a tenement, she had declared war against her half brothers, the bank, and all other exploiters of women, children, and the poor. She would get into fights with bullies at school and almost took one’s eye out with a shovel. As a teenager, her contempt expanded to authority figures in general, and she was arrested a dozen times. It was about that time that men like Barker began looking at her in uncomfortable ways and making unnerving comments. At first she would throw punches or scratch their faces, but she came to realize that her good looks could work for her as well as against her. She saw how boys would blush and be sweet if she seemed to take a shine to them but would say nasty things and get rough if she didn’t. Her insight didn’t mute the anger, of course, not in the slightest; it just showed her how someone weaker and poorer could gain an advantage if she kept her wits about her.

She grew into a striking young woman, which only led to more problems—more wounds, more anger, more arrests. She joined the labor movement, thankful to find like-minded people who shared her sense of injustice, and for the first time since her father’s death and living hand-to-mouth, she felt something akin to happiness. She laughed and sang and chronicled accounts of brave strikers setting up picket lines and goons bashing their skulls. Her love affair with writing blossomed, and she became a compelling storyteller, a talent nurtured by spellbinding union men out to organize local mills and mines. But those fellows couldn’t keep their hands off her either, and she had to quit the movement after slicing off one organizer’s ear when he forced himself upon her.

She had felt the same destructive urges when Barker was taking liberties in his office, but she had held back with a greater purpose in mind. She wasn’t sure if that was a sign of progress or weakness. Or maybe she would just give Barker his just desserts when the time came.

Unlike Barker, Francis A. Ingram took a noble approach to medicine. Perhaps it was the idealism of youth—Ingram was only 32—or his apprenticeship as an Army surgeon during the Indian wars, but in addition to maintaining a regular practice near Union Square and founding the New Jersey Medical Society, he was the assistant superintendent at Bellevue Women’s Asylum. All this despite a constitution left weak by his mother’s rubella when he was still in her womb. The Bellevue position was nowhere near as lucrative as private practice, but Ingram was caught up with the wave of mental illness theories sweeping Europe and the U.S. He had read everything by Brucke in Germany and Charcot in France that he could get his hands on, and he engaged them both in a regular correspondence based on his detailed observations at Bellevue.

Nellie had been taken to Ingram during her undercover work at Bellevue for complaining about cold baths in the middle of winter. He had discerned immediately that she was faking her illness, but after confronting her, he played along because he, too, found the conditions appalling and hoped she might change them. Ingram became a valuable resource, and she mentioned him favorably in her stories. He had also been one of the few men in New York not to undress her with his eyes, and she appreciated that as well. When she had questions about Barker’s diagnosis and care of Emma Lazarus, it was only natural she would turn to Frank Ingram for answers.

Ingram’s private office was in the basement of a three-story brownstone on Twenty-First Street. His receptionist, Edith Fairley, the middle-aged, pear-shaped widow of a former colleague, did not care much for Nellie. On her desk she kept a clipping from the Boston Transcript that warned, “Homes will be ruined, children neglected, all because woman is straying from her sphere.” For Edith Fairley, Nellie represented all that was becoming wrong with America.

The reception area was devoid of patients, as Nellie knew it would be, when she walked in with Mary Jane. Ingram tended to see patients in the morning and early afternoon and caught up on correspondence and research late in the day.

“Good afternoon, Mrs. Fairley.”

“Good afternoon,” replied Mrs. Fairley frostily.

“This is my mother. Mrs. Cochran.”

“How do you do, Mrs. Fairley?” said Mary Jane politely.

“How do you do?” replied Mrs. Fairley with no warmth whatsoever.

“Is something wrong?” asked Mary Jane.

“No. Should there be?”

“When you can’t even give a proper hello, I’d say there is. You sick or something? Someone die in your family?”

Nellie let the words linger. She had no desire to lessen Edith Fairley’s discomfort.

“Is Dr. Ingram in?” asked Nellie.

“Is he expecting you?”

“No. But I need to see him. Please tell him it’s important.”

It was a directive, not a request. Mrs. Fairley knew enough not to defy Nellie and went to the rear hallway, but her horselike snort made her feelings known nonetheless. Nellie didn’t care. She was used to it. Women like Mrs. Fairley were as resistant to change as the men she encountered. Maybe even more.

“Who does she think she is?” asked a perturbed Mary Jane. “Back home she wouldn’t last ten minutes with a manner like that.”

“Her husband was a friend of Doctor Ingram’s.”

“I bet he’s happy to be dead.”

Mrs. Fairley came out of the interior office, the picture of disappointment. “The doctor will see you. He is finishing a letter and will meet you in the examining room.”

“I can show myself in. Mother, wait here please. I won’t be long. Mrs. Fairley will keep you company.”

“Well, that should be fun.”

Nellie went down a corridor and entered a room on the left. It was dark, with gas lanterns and azure blue shades, furnished with a burgundy Oriental rug, an examining table, a mauve couch with tassels, an oak French Empire sitting chair, and a wooden desk with medical instruments and an ink well. Nellie, still worked up from her meeting with Barker, paced about the room.

The door opened, and an earnest man of medium height, tired but gentle eyes, thick glasses, taut skin, and a professional air, with a tie and woolen suit that made him look considerably older than early thirties, walked in.

“Miss Bly. Good afternoon.”

“Hello, Dr. Ingram.”

He closed the door behind him, and they rushed to embrace in a deep, passionate kiss. She clutched his lapels and pulled him to her while his hands slipped under her skirt and inside her undergarments. She moaned at his touch but pulled back.

“We can’t,” she whispered. “Mother is outside.”

“In the reception area?”

“Yes.”

His hands still on her buttocks and moving to the inside of her thighs, he tried to pull her toward him, but she resisted.

“I’m sorry,” she said. “Next time. I promise.”

“I can make it quick.”

“I don’t want it to be quick.” She kissed him hard, making clear her hunger for him.

It was during the latter stages of the Bellevue story that Nellie’s relationship with Ingram went beyond the platonic. She would meet him in his office nearly every afternoon to obtain information and go over records. His indignation with Bellevue had matched hers, and for a journalist, he was a gold mine. She was drawn to his heart, his mind, and his spirit, and to his vulnerability—his mother’s rubella had left him with poor eyesight and shortness of breath. To Nellie’s constant surprise, he never made a single advance toward her. Only later did she learn that he ached for her constantly, but he sensed the deep pain and anger inside her and had concluded that any step toward intimacy would have to come first from her or she would become mistrustful and hurt, and he could not bear the thought of that. He told her that he admired her so much, he was prepared to restrain himself even if nothing sexual ever happened between them. But Nellie did develop a trust, pushed along by desire, and one afternoon she simply held his face in her hands, kissed him tenderly, removed his clothes, and made love to him. At nearly every session after that, they made passionate love and then continued on with the work. Ingram never asked anything of her, never demanded or ordered or insisted. He left it up to her to set the boundaries, and she came to trust him as she had never trusted another man.

Yet that trust had its limits. Nellie had been too betrayed, too mistreated by the world to trust Ingram completely. Though she was falling in love with him, she always held something back. It was imbued deeply inside her, and as a result they never discussed their feelings for one another. Nellie wanted to tell him she trusted him so much it frightened her, that she yearned to be with him constantly and wanted to share her innermost thoughts with him, but she could not say such things, at least not yet, not even to herself. Ingram, for his part, felt just as reticent, but Nellie knew his hesitation was due only in part to protectiveness toward her. He was also driven by his work and was struggling to grasp where his emotions for her fit in with his ambitions. And so he, like her, would enjoy what they had and hope it did not vanish too soon.

“What explains this visit, or are you simply here to frustrate me?” asked Ingram as Nellie managed to pry herself away.

“Sit down and I’ll tell you.”

She led him over to the couch, clasped his hand, and told him about the events of the day, including the office visit with Barker. Even though she euphemized the most personal details, Ingram’s fists tightened at hearing a physician abuse a patient like that, especially Nellie.

“What do you know about Barker?” she asked.

“I think he should be horsewhipped.”

“I meant as a doctor.”

The New York City medical community was small; fewer than 500 men called themselves physicians. Ingram, she knew, as one who approached medicine as a science and believed strongly in the importance of exchanging information with colleagues, made a point of knowing as many doctors in New York and New Jersey as he could.

“What is it you want to know?” he asked.

“Is he a good doctor?”

“No.”

Nellie smiled. She liked Ingram’s candor.

“I don’t think he knows what he’s doing,” she said.

“He doesn’t.”

She didn’t bother asking how Barker, a Yale man, managed an appointment at the new Cancer Hospital. That question answered itself. She had more important matters in mind.

“Why would Emma Lazarus see him?” she asked. “She was an intelligent woman. She must have known he was mediocre.”

“Most likely she did not want her family to know about her medical matter.”

Nellie looked at him with surprise.

“You think she was pregnant?”

“Not necessarily. She could have seen him for other reasons.”

“Such as?”

“Are you aware of the Comstock Act?”

“I believe so. It makes pornography a crime.”

“Yes. But its definition of ‘pornography’ includes any discussion of contraception.”

“You mean it makes contraception illegal?”

“It makes even discussing contraception illegal.”

He did not need to elaborate. More than emancipation of the slaves, more than women getting the vote, contraception—the possibility of sex without risk of pregnancy—was the most threatening prospect in America. Sex without risk would mean the liberation of women and unbounded pleasure, i.e., the end of the American character and the very foundation of the country. Charles Goodyear had patented the first rubber condom in 1844, and by the 1870s, there was such widespread use of intrauterine devices and diaphragms that the number of women dying in childbirth had dropped by 30 percent in twenty-five years. Nevertheless, the prospect of sex without fear of pregnancy—and the emancipation of women—so appalled morals keepers of the time that thirty-four (out of thirty-eight) states passed laws outlawing dissemination or discussion of any contraception materials. Nor were these laws merely harmless platitudes. Anthony Comstock, the author of the federal law that bore his name, boasted that he was responsible for four thousand arrests and fifteen suicides.

“Miss Lazarus may have simply wanted someone discreet to protect her from becoming pregnant,” said Ingram. “How did she find out about Barker?”

“From a college friend of his. Mr. Charles DeKay.”

“The critic at the Times?”

“Yes.”

“Was she intimate with DeKay?”

“I don’t know. Possibly.”

“Well, that might explain why she saw Barker.”

Of course. Why else would she see an oaf like Barker? “Ingram, you are brilliant.”

“No. You are brilliant.”

“You’re right. I am brilliant,” she said, making him smile and clasping his hand even tighter. She felt so at ease, even girlish with him. She leaned against him as he put his arm around her.

“But you still have a problem,” he said. “The doctors she saw in England were superb. If they concluded she had cancer, she almost certainly did.”

“And her symptoms were all consistent with cancer. Even if her doctor here was a fool.”

“Then what is your story for Mr. Pulitzer?”

“I don’t know,” she said glumly.

She sat there quietly, nestled in his arms, quietly running her fingers over his hand. She remembered something else about her conversation with Barker.

“Would you ever give arsenic to someone in Emma’s condition?” she asked him.

“Never.”

“Barker did.”

“He couldn’t have. Arsenic increases pain.”

“He denied giving it, but I know he was lying.”

“Then he is an even worse physician than I thought. If she was in the advanced stages of lymphatic cancer, his sole concern should have been making her comfortable. Once a patient is certain to die, you stop prescribing arsenic. It only accelerates death and makes the last days extremely unpleasant. Even a fool like Barker knows that.”

“And yet he ordered it for her.” And then it hit her.

“What are the symptoms of arsenic poisoning?” she asked.

“Fatigue. Weight loss. Exhaustion.”

“The same as cancer.” It was becoming clearer to her.

“To the layperson, yes.”

“So it’s possible she was dying of cancer but was still poisoned, and the poison is what actually killed her.”

“Yes. Of course. Very possible.”

She sat upright. “How would I prove it was poisoning?”

“You would compare her blood samples in England with blood samples here just before her death. If the arsenic levels here were as high or higher, she was poisoned.”

“Wouldn’t the blood samples be destroyed?”

“No, the Cancer Hospital keeps vials for future research. As do the doctors in England. We should be able to obtain samples from both places.”

“Ingram, you are fantastic.”

She kissed him on the lips and jumped to her feet.

“But even if you can show she was poisoned,” said Ingram, “you still don’t know who administered it to her. Or why. Barker simply prescribed it.”

“I have a good idea where to start.”

For the first time since Pulitzer gave her the assignment, she was excited. She might have a story after all. She started to open the door but stopped and looked at him. She felt such love and warmth in her heart for him, and there was love and warmth on his face, but she could not bring herself to tell him she adored him.

“Thank you, Dr. Ingram.”

“My pleasure, Miss Bly.”