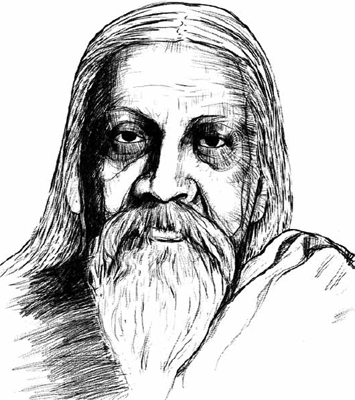

Aurobindo Ghose

Swaraj is neither a colonial nor any other form of government. It means the fulfilment of our national life. That is what we seek.

—Aurobindo Ghose

The boy grew up as a little sahib. Even though they were Bengalis, the Ghose family lived like the English. The children wore frilly shirts and trousers, sat down to meals at a dining table laid with knives and forks and had a governess who taught them the ways of those to the manor born. The family lived in many Bengal towns where they mixed only with Europeans and the children were kept away from any Indian influences. As a matter of fact, the boy learnt to speak only a little Bengali and broken Hindi from the family butler when he was five years old.

The boy’s anglophile father would have been very surprised if he had known that one day his son would become one of the most fascinating and many-faceted characters of the freedom movement—a writer and poet, a revolutionary dreaming of driving the British out of India, and then a famous Hindu mystic.

Aurobindo Ghose was born on 15 August 1872 in Calcutta. His father Krishnadhan Ghose was a doctor in the government medical service and his mother Swarnalata was the daughter of Rajnarayan Bose, a famous Brahmo scholar who believed in religious and social reform. They belonged to a rich zamindar family and Krishnadhan had gone to study in England, defying the caste laws that ordained that you would lose your caste if you travelled across the seas. He came back to India, the perfect brown sahib, completely enamoured of European civilization and convinced of the superiority of the West. So he named his third son Aurobindo Ackroyd Ghose!

The three older Ghose boys were first sent to a Darjeeling convent to study and then taken to England. Here they stayed in Manchester with a Reverend Drewett and the older boys went to a grammar school. As Aurobindo was only seven, he was tutored at home in the beginning. Their father left strict instructions that the boys were not to mix with Indians. When the boys moved to London to study at St. Paul’s School, the money from India arrived erratically and they were at times close to starvation. Aurobindo remembered facing the English winter without an overcoat and sleeping in an office. They survived for days on a few slices of bread and butter and tea for breakfast and a single penny-roll of bread and sausage in the evening.

In spite of such hardships, Aurobindo was a brilliant student, winning many prizes at school and then going to King’s College, Cambridge on a scholarship. He was a budding poet, composing verses in Latin and Greek, and won a Tripos—a three-part degree—in classical languages. It was in Cambridge that, at the age of twenty, Aurobindo first made some Indian friends. He joined a society of Indian students called Indian Majlis and became its secretary. He even toyed with revolutionary thoughts by joining a secret society rather dramatically called ‘The Lotus and Dagger’ but it didn’t last very long. By this time his father had also become disillusioned with the British and begun sending him newspaper cuttings about British oppression of Indians.

Aurobindo’s father wanted him to take the entrance exam for the Indian Civil Service, which he passed easily, but then as he failed to appear for a horse-riding test, he was not admitted into the service. Later he admitted that he had taken the exam only to please his father and was really interested more in ‘poetry and study of languages and in patriotic action.’ Fortunately for him, the ruler of the princely state of Baroda, Sayajirao Gaekwad, was in London at that time and, after an interview, offered Aurobindo a post in the state service. At a time when most princely states were very badly run, Baroda was an exception. Sayajirao often offered jobs to talented and educated Indians and had some of the best schools and colleges in an Indian state. Some years later he would give a scholarship and a job to an untouchable boy named Bhimrao Ambedkar.

Aurobindo had left India at the age of seven and came back at twenty-one. He returned in February 1893 on board the ship SS Carthage and immediately faced a family tragedy. His father had been informed by his London bankers that Aurobindo was travelling by another ship, the SS Roumania and that the ship had sunk at sea. The shock had killed his father.

Aurobindo Ghose soon joined work at Baroda and became the Gaekwad’s personal secretary. His command of the English language meant that he wrote all the king’s speeches and handled the correspondence with the Government of India. However the young man chafed at having to be at the beck and call of the ruler.

After a while Ghose began to teach French and English at Baroda College and would one day become its principal. Many of his students remembered him as a mesmerizing speaker and he became a legend as a teacher. This was the time when he began to discover his motherland, and as is often the case with those who find their roots late in life, his passion was overwhelming. Ghose wanted to know everything about India immediately. He knew seven languages but could not converse in his mother tongue. So he taught himself Sanskrit, and got teachers to teach him Bengali, Marathi and Gujarati. Crates of books began to arrive from Bombay and his reading spanned everything from the Vedas to the writings of Kalidasa and Bankim Chandra Chatterjee.

The writer Dinendra Kumar Roy came from Calcutta to teach him Bengali and later wrote about his first view of his very unusual pupil: ‘I had imagined him as a tall, stalwart figure, dressed from head to foot in immaculate European style, bespectacled, with a stern, piercing look and an affected accent, quick-tempered and intolerant. Frankly, I was a little disappointed when I saw him. Here was a shy, dark youth, his gentle eyes filled with dreams, his long, soft hair, parted in the middle and flowing down to the neck. He was dressed in a thick coarse dhoti and close-fitting Indian jacket.’ Ghose had finally become an Indian.

Soon Ghose joined the nationalist movement enthusiastically, meeting leaders and attending sessions of the Congress party. He left Baroda and shifted to Bengal where he began to edit the journal Bande Mataram. At that time Bengal was in a ferment of protest over the partition of the province by Lord Curzon and Ghose was one of the most vocal members of the radical group in the Congress, called the Extremists. Their leaders Tilak and Lajpat Rai wanted to start an India-wide agitation in cooperation with the moderate leaders like Gokhale, but their rather excitable band of followers were not interested in any form of compromise.

The two groups came into open conflict at the session in Surat in 1907, when after a tumultuous meeting, the party was virtually divided. The young men went on a rampage, shouting down the speakers and even throwing a shoe on to the stage. Tilak failed to control his followers and the session ended with the police clearing the pandal. Many people blamed Tilak for starting the fracas, but many years later Ghose admitted that it was he and his friends who had started it all without Tilak’s knowledge.

Meanwhile, Ghose had started the newspaper Jugantar and continued to write a stream of articles criticizing the government and fiery poetry inciting people to join the Swadeshi protests. He also began to teach at the National College (later, Jadavpur University) that had been set up for students who had been expelled for joining the Swadeshi Movement. He was arrested and charged with sedition for his writings in Bande Mataram but was acquitted.

At this time Bengal had become a hotbed of revolutionary activities, with secret societies springing up everywhere. One of them was led by Ghose’s younger brother Barin who began to train young men in the use of arms and making bombs at their family home at Maniktala Gardens. In 1908 two young men—Prafulla Chaki and Khudiram Bose—tried to kill an ICS officer named Kingsford but instead threw the bomb into a carriage carrying two Englishwomen, who were both killed. The police raided the Maniktala house where guns and bombs were found, and Barin and his friends were taken into custody. Ghose was also arrested—even though there was no direct proof of his involvement—and charged with waging war against the King. The penalty for the offence was death. He was in jail for a year before the trial began.

The trial came to be known as the Alipur Bomb Case; it was the first revolutionary case in India and it gripped the country. C.R. Das, the most successful barrister in the city, came forward to defend Ghose. In his argument he said about Ghose, ‘… long after the controversy will be hushed in silence, long after the turmoil … he will be looked upon as the poet of patriotism, as the prophet of nationalism and the lover of humanity.’ Curiously, the judge at the trial, C.P. Beachcroft, had been Ghose’s classmate in Cambridge—he had been beaten by Ghose in Greek but had bested him in Bengali!

Ghose was acquitted. The government made it clear that it was very unhappy with the verdict and would arrest him at the first opportunity and deport him. Friends of Ghose like Sister Nivedita—an Anglo–Irish social worker in India—feared for his life and advised him to leave British India and live in a French territory. Ghose first moved to Chandranagar in Bengal and then sailed for the French enclave of Pondicherry in Tamil Nadu. When he landed in Pondicherry on 4 April 1910, he was welcomed by a group of nationalists who were living there in exile and among them was the Tamil poet Subramania Bharati.

Everyone knew of Aurobindo Ghose, the poet of freedom, the firebrand leader, but there was also a spiritual side to his character. He was deeply interested in philosophy and mysticism and he had spent years studying Hindu philosophy and meeting thinkers and yogis. In Pondicherry, Ghose was far away from the hurly-burly of nationalist politics and now he let this hidden side surface. He believed that India’s independence was inevitable and that there were many leaders who could lead the country to Puma Swaraj—complete independence. Now he could withdraw and concentrate on his spiritual journey of thought and meditation.

It was the final transformation in an amazing life. First the anglicized sahib who could not even speak his mother tongue became a popular writer and poet in Bengali, whose dreams for his beloved motherland inspired a nation. Then he was the radical revolutionary who approved of violence as a means to gain freedom. And now in his forties, he became a recluse, seeking spiritual truths through meditation—one day he would be called the ‘Sage of Pondicherry’.

Aurobindo Ghose—scholar, poet and revolutionary—now became Shri Aurobindo, philosopher and mystic. A new journey into the uncharted waters of the mind had begun.