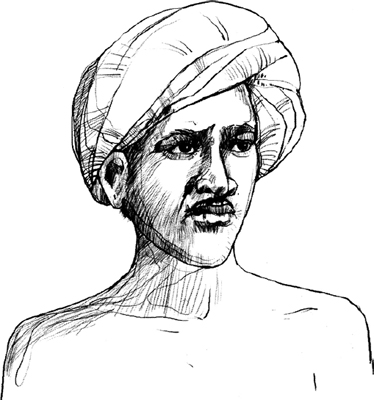

Birsa Munda

Maharani raj tundu jana oro, abua raj ete jana.

(Let the kingdom of the queen be ended and our kingdom be established.)

—Birsa Munda

He was the charismatic leader of the Mundas. This tribe lives in the Chhotanagpur region of what is now Jharkhand and they rose up against the oppression of the landlords and the British government at his call. The Mundas fearlessly faced the guns of soldiers with bows and arrows, spears, axes and catapults, as their faith in their leader Birsa Munda was absolute. For the tribal he became Bhagwan, their deity, and they believed he would lead them to freedom.

Birsa Munda was born at Bamba, near Ranchi, on 15 November 1875. It was a Thursday and he was named Birsa after the day as was Munda custom. His father was a sharecropper or ryot. The family lived in a poor house built of bamboo and wandered from village to village in the Chhotanagpur area looking for work. Soon after Birsa’s birth, the family left for Chalkad. His father Sugana Munda had been converted to Christianity much before Birsa’s birth and later became a pracharak of the German missionaries. Birsa grew up like other Munda children, grazing sheep, and is said to have been skilled at playing the flute and the tuila, a single-stringed instrument made from the pumpkin.

The family moved to Ayubhatu in search of work and then Birsa went to live with his elder brother at Kunda Bartoli. After that, probably in Burju, Birsa attended a Christian missionary school for a while and got an elementary education. For a while he even became a Christian, but later he discovered Vaishnavism and became a worshipper of Vishnu. He turned vegetarian, wore the sacred thread and began worshipping the tulsi plant.

Birsa lived at a time of great social and economic tumult among the tribal people of the region. At one time they were free to lead their lives—they cleared the forest for crops and gathered the wealth of the forest like fruits, honey, plants and wood. They had grazing rights on common land that was owned by the whole community. The forests were their home and there was tacit acceptance by local rajas like the Raja of Chhotanagpur that it belonged to the various tribes.

All this changed with the arrival of the British, the officials and the missionaries. The tribal kings and leaders called Sardars were defeated and forced to pay tribute and the government insisted on the imposition of taxes on the tribes. Then the Christian missionaries arrived with their strange social rules and alien culture. Tribal society was comparatively free of caste or religious divisions and everyone, men and women, were equal. The missionaries began converting them by offering converts special privileges; this led to social divisions and much anger and resentment in the villages.

Now the government revenue collectors—the hated thikadars—arrived, followed by moneylenders and landowners who cheated the simple tribal people of their land. The tribes lost the land they had cleared and cultivated because they had no legal papers to prove they owned it and were often reduced to becoming farm labourers and often bonded workers. Many were forced into bonded labour called beth begari and others made to pay exorbitant rents by the mercenary thikadars. The Mundas began to hate and fear the Dikus, the non-tribal people of the area, and one day that anger would make these peaceful people pick up their bows and arrows in sheer desperation.

The Munda uprising was one of many among the tribal people of the region and they died by the thousands. The Santhals rose in 1855–56 and were crushed ruthlessly by the police. Among the Mundas there was first the rebellion led by the Sardars. The Sardars had earlier tried to ally themselves with the missionaries, but disappointed, had turned against them. A young Birsa joined the Sardari agitation, denounced the missionaries and began to believe that all white people—the British and the missionaries—were the same. He was jailed for two years and came out even more of a firebrand; now he claimed he had a revelation from God, which said that the land belonged to the people who cultivated it. Birsa also said that this was the kingdom of the Mundas and no one had the right to impose any taxes on them. The Sardars were against the thikadars but they had always acknowledged the sovereignty of the King of Chhotanagpur—but now Birsa claimed the forests for his people.

Birsa was barely in his twenties when he burst upon the scene claiming to be a messiah, a healer and miracle worker, and was soon being worshipped as ‘Bhagwan’ and ‘Dharti Abba’, the father of the land. His ideology was a mix of his religious beliefs and the economic demands of the people. He was a religious and social reformer, and spoke with surprising maturity for his age. He dismissed superstition and discouraged the Mundas from converting to Christianity as it led to divisions in the Munda society. He asked his followers to give up animal sacrifice, criticized their faith in magic and spirits, and asked them to stop drinking liquor. He wanted them to go back to the old traditions that worshipped the forest and then help him throw out the hated Dikus from their land.

In December 1899, Birsa Munda led the Ulgulan or the Great Tumult, with his followers moving from village to village claiming freedom from the rule of the British Maharani Victoria. They prevented the Forest Department from taking away the village common lands. Then bands of armed tribals attacked the thikadars, burned down churches and fought the police in the Ranchi–Singbhum area. For a while Birsa and his men controlled the land and there was panic in the town of Ranchi as people feared that it was to be the next target of the Ulgulan.

The tribal men and women, armed with just bows and arrows, spears and catapults, fought with unbelievable spirit against the guns of the police and army, but their defeat was inevitable. Nearly three hundred and fifty Mundas were put on trial, three were hanged and forty-four were given jail sentences. Birsa Munda was captured and died in jail a few months later on 9 June 1900. He was only twenty-five years old.

The Great Tumult was over, but Birsa was not forgotten. First, it made the government take the grievances of the Mundas against the thikadars more seriously and also acknowledge their hereditary rights to the forests. A new act, the Chhotanagpur Tenancy Act of 1908, gave them more rights to the forests and banned bonded labour. It was not a perfect solution but at least the Mundas had some legal rights to their land.

Since then Birsa Munda has become an icon of the tribal people’s fight for their traditional rights, even in modern India. Today his statue stands in the Indian Parliament and he is a legend in the state of Jharkhand. There is also a statue of Birsa in the capital Ranchi and the airport is named after him. What he achieved through his rebellion was that he made the tribal people aware of their rights and give them the courage to stand up and fight for them. Even today a religious sect called the ‘Birsaites’ worships Birsa Munda as a deity.

The Ulgulan was one of the most well known of many such rebellions of peasants and tribal people all across India against the oppressive demands of the British government and the exploitation of zamindars and moneylenders who always had the might of the police on their side. All these agitations were around specific causes, and usually once their grievances were attended to, they died down.

Though influenced by the Sardars, Birsa was not fighting for their cause. He had a mission of his own—to fight for his fellow Mundas. The ideal ‘Munda Raj’, as he saw it, would be possible only if the European officials and missionaries were expelled from the scene. He had no conception of a nation called India, nor was he leading a nationalist movement for the freedom of the country, yet what was unique about Birsa Munda was his ability to organize a rebellion that united his people and made the government listen to their grievances. At the young age of twenty, he had begun to worry the British government quite a bit. He dismissed the suzerainty of the British monarch and the power of the local king, and claimed the land for his people. He showed the way to make the powerful listen to the poor and forgotten tribes. He was the passionate voice of his people and today he is the symbol of the poor and marginalized peasants and tribal people in independent India, inspiring them to find the courage to stand up and fight for their rights.