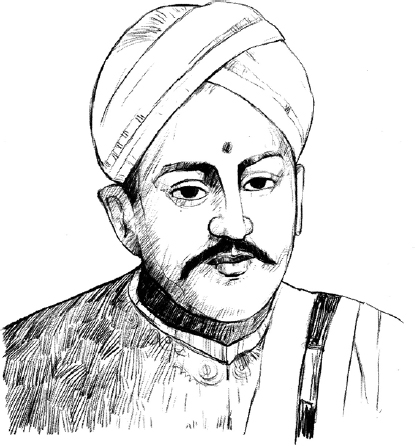

V.O. Chidambaram Pillai

He was ‘Kappalottiya Tamizhan’–the Tamilian who sailed the sea.

– M.P. Sivagyanam, biographer of V.O.C. Pillai

It was a special day in the coastal town of Tuticorin in Tamil Nadu. On 9 February 1949, the Governor General of India C. Rajagopalachari had come to launch a ship. To the cracking of a coconut, loud cheers and a band playing, the ship slid into the water and the watching crowd all read the name painted on its bow—Chidambaram. The ship had been named after V.O. Chidambaram Pillai, the man who took the Swadeshi Movement to the sea.

Vulaganathan Ottapidaram Chidambaram Pillai was born on 5 September 1872 at Ottapidaram in Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu. He was the son of Vulaganathan Pillai—a lawyer—and his wife Paramayee. He first studied in a primary school started by his father and then completed his schooling from St. Francis Xavier High School in Tuticorin. He studied law at Tiruchirapalli and then began his practice at the magistrate’s court in Ottapidaram.

Popularly known as ‘VOC’, Chidambaram Pillai often took on the cases of the poor, knowing very well that they would not be able to pay him high fees. He would at time plead cases even against his father who preferred more affluent clients. Soon Pillai began to protest about the corruption in the law court and was furious at being offered a bribe to withdraw a witness in a case. Then in 1900, when he proved corruption charges against three sub-magistrates, his father’s anger made him leave home and start practising law at Tuticorin.

Pillai joined the Indian National Congress and in 1905 he became involved in the Swadeshi campaign led by Bal Gangadhar Tilak. When Pillai led the Swadeshi agitation in the Salem region, first his own foreign clothes, even pens, knives and combs went up in a bonfire. Then shops selling foreign goods were picketed and processions taken out against the partition of Bengal. He even walked out half-shaven from a barber’s shop on discovering that the man was using a foreign razor! Pillai travelled from town to town, giving passionate speeches and building awareness of the Swadeshi campaign, and soon the government took note of his activities.

Pillai had grown up near the sea and he now thought of the great tradition of south Indian maritime trade. At one time the ships of the Pallava and Chola kingdoms had voyaged across the Indian Ocean to reach places as far away as Cambodia and Java. Now the British steamship companies monopolized shipping along the eastern coast. Pillai had already started Swadeshi stores where Indian-made goods were sold, and now moving one step further, decided to compete with these shipping companies. When the news spread that he planned to start a shipping line, some of the wealthy local merchants came forward to help him with loans.

On 12 November 1906 V.O.C. Pillai formed the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company by renting two ships. Later he bought two ships—the SS Gaelia and SS Lawoe—and won the praise and support of Tilak and Aurobindo Ghose. The ships began regular service between Tuticorin and Colombo, carrying passengers and goods. So far this route had been hogged by the British India Steam Navigation Company and their local agent A&F Harvey. They had expected Pillai’s venture to fail but soon found they had a tough competitor. The British company first lowered its passenger fare to just one rupee; Pillai responded by charging a fare of eight annas. Unfortunately, the British company had deep pockets and began to offer free passage and Pillai’s ships began to run empty. By 1909 the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company was close to bankruptcy.

At this time Pillai had also begun trade-union activities and, in 1908, he led a strike at Coral Mills, demanding higher wages for the workers. This textile mill was also owned by A&F Harvey and at their complaint the administration moved swiftly and arrested Pillai. The response surprised everyone—there were violent protests in Tirunelveli and Tuticorin, and four people were killed in police firing. Panic struck the British and finally the textile company gave in and agreed to raise wages. However, Pillai was not released.

Pillai’s arrest and trial was also a result of the recent events in the Congress. As a supporter of Tilak, Pillai had attended the Surat Congress in 1907 with the poet Subramania Bharati and was present when the party split into Extremists and Moderates. This unfortunate division badly weakened the party and it became inactive for some years. The government took advantage of this sudden cessation of the Swadeshi Movement and arrested and jailed many leaders. Tilak was sent to the prison in Mandalay in Burma, and Pillai was arrested and kept at Coimbatore Jail.

There was an unprecedented public outcry at Pillai’s trial, with protests all across the region. Madras newspapers covered the trial proceedings and even the Ananda Bazar Patrika of Calcutta carried daily reports. Funds flowed in, not just from across the country but even from Tamils in South Africa. During the trial Pillai was charged with sedition; Subramania Bharati and the freedom fighter Subramania Siva appeared in his defence. When Pillai was found guilty, the severity of the sentence shocked the nation. He had been sentenced to forty years, the length of two life sentences, and was to be sent to the notorious Cellular Jail in the Andamans. Pillai appealed to the High Court. At the same time Lord Morley, the Secretary of State for India wrote to the viceroy, Lord Minto, saying that he feared unrest in Tamil Nadu unless the sentence was reduced. The case finally went up to the Privy Council; the sentence was reduced to six years of rigorous imprisonment. By then this long and expensive legal battle had financially ruined Pillai’s family.

In Coimbatore Jail, Pillai was treated like a common criminal and forced to do hard labour. In unbearable heat he had to break stones, even pull an oil press in place of bullocks and was given little to eat. His health began to fail, and by the time he was released in December 1912, he was a broken man. Pillai had gone to prison a hero with huge crowds out in the street in his support. He came out to discover he had been forgotten. The country was quiet, Tilak was still in jail, the Swadeshi Movement that had created such excitement was over and there was no activity in a weakened Congress. His ships had been auctioned to pay off debts and the shipping company had been liquidated.

For the rest of his life Pillai continued to work in the Congress but struggled constantly with poverty and ill health. He completed his autobiography in Tamil verse that he had begun while in prison and now wrote erudite commentaries on Tamil classics and even translated English novels into Tamil. He carried on a long correspondence with Mahatma Gandhi, though he never quite approved of Gandhi’s Satyagraha.

His admirers used to call him ‘Kappalottiya Tamizhan’—the Tamil who sailed the sea—and ‘Chekkiluththa Chemmal’, the man who pulled an oil press for his people. V.O. Chidambaram Pillai died on 18 November 1936 at the Congress office at Tuticorin, a fitting place for the last goodbye of a man who showed India that with enterprise and courage Swadeshi could succeed.