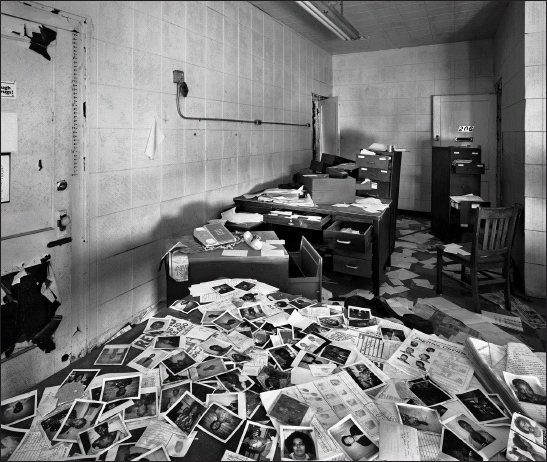

Abandoned Highland Park police station. [Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre]

AUSTERITY 101

NO MATTER HOW dextrous or well-intentioned our elected officials, any plan to reinvent Detroit, or even adequately address the city’s most fundamental crises, required the one thing Detroit lacked most of all: unimaginable amounts of money. As John Mogk, the Wayne State law professor and urbanist, pointed out, Detroit’s major recent success stories have been obtained in large part through spectacular levels of capital investment. “If you reach back to the sixties,” he said, the housing development of Lafayette Park “has probably experienced a billion dollars a mile in public and private investment. Midtown”—which includes the university and hospital districts—“in the two miles from the Fox Theater to Grand Boulevard, has probably experienced a billion a mile over the past ten years.”

Mogk contrasted this healthy area of Detroit, which he calls the Core, with the other 130 square miles of the city, which he calls the Heartland—historically the strength of Detroit, a city never known for its downtown as much as for its industrial plants, strong neighborhoods, and high levels of home ownership. The Heartland, Mogk noted, has been steadily deteriorating. “And that’s where all the problems are,” he says. “And the only part of that whole area that’s received anything commensurate with the level of investment in the Core area has been the Poletown Plant and the Chrysler Jefferson Plant. So, as Core Detroit becomes more closely linked with the suburbs, Heartland Detroit is drifting off on its own. To focus on what’s happening in the Core area really creates a false sense of future hope. If you look at the income distribution in the city and ask me if the Heartland is coming back, well, are you kidding me? Cities are not built or rebuilt for low-income residents. It would be nice if they were. But that just doesn’t happen.”

As municipalities across the globe stare down varying levels of financial catastrophe, the notion of increasing investment in failing communities such as the Mogk-defined Heartland has become folly, with the terms of debate instead shifting almost entirely to discussions of debt reduction and austerity. The received, morality-tale version of the salvation of the auto industry, often recounted in the form of a self-help recovery narrative, in which the mulish executive-suite occupants were forced to hit rock bottom before making the “hard choices” necessary for survival, has more recently been applied to ever more insolvent governmental entities, which have been painted as the functional and moral equivalents of GM or Chrysler, that is, bloated and inefficient bureaucracies unwilling to change with the times, get tough on labor, and become “lean” and “competitive.” Like the Big Three, we were all being told that our cities and states—along with their citizens and public servants—needed to discard childish illusion and accept that aspects of American life had changed forever.

In this context, the Michigan legislature adopted the Emergency Financial Manager law, which deficit hawks cast as a top-down, stern-father means of enforced frugality, necessary for irresponsible charges who had proved incapable of making, and abiding by, a budget. The fact that most of the cities facing possible EFMs were, like Detroit, contending with all of the problems associated with concentrated poverty (including the absence of any sort of real tax base) tended to be glossed over, though it was hard to see how any of this could end well: cities like Detroit already barely delivered on the most minimal of public services, and the idea of forcing even more cuts, somehow rooting out “waste” in the system, moved beyond the vague shared-sacrifice campaign slogans employed by politicians across the spectrum and began to enter the realm of field amputation.

For those who wish to observe the effects of austerity measures taken to their natural extreme, one local Galapagos-scaled ecosystem worth studying is Highland Park. Located about six miles from downtown, Highland Park is technically not part of Detroit at all but its own separate municipality. (Though one surrounded on all sides by Detroit, so central on a map of the city it practically marks a bull’s-eye.) In the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1805, the federal government had given Michigan territorial officials permission to sell state property in order to fund the rebuilding of Detroit. Part of the unloaded land, a patch of mostly swamp, passed through the hands of a series of developers who hoped to turn the place into a viable township. As developers are wont, they seized upon one of the most appealing aspects of the local landscape—the few hills punctuating the marsh—to come up with the prototypically suburban name of Highland Park.1

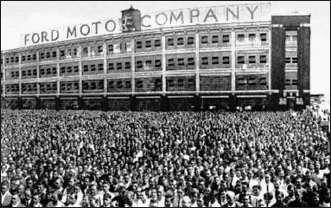

One of the would-be developers was Judge Augustus Woodward, who proposed naming the village Woodwardville. But his plans didn’t go anywhere, and nothing much happened with Highland Park until Captain Will H. Stevens, a one-eyed veteran and former Colorado prospector, managed to get the swamp drained, making the land inhabitable, if not yet desirable. When Henry Ford relocated to Highland Park in 1906 to radically expand his production capability, the area surrounding his new factory was predominantly farmland. There were also modest shoe and wagon factories, a general store, and a blacksmith’s. The site of Ford’s world-changing Model T plant had once been a hotel resort and spa, with mineral baths and a neighboring harness racing track. In 1910, the year the factory opened, the population of Highland Park was 425. By the following year, it had grown to 4,120, and by the end of the decade, it had become 46,000.2 Highland Park resisted annexation by Detroit at the behest of Ford, the city’s largest corporate citizen, as part of a blatant tax dodge. The tiny Polish enclave of Hamtramck, also surrounded by Detroit, pulled a similar move around the same time to create a tax haven for its Dodge plant, robbing Detroit, even in those boomtown years, of revenues from two of its most productive factories.

As recently as the fifties, Highland Park, called the City of Trees, boasted one of the area’s most desirable addresses. Even after Ford decided he needed more space for his manufacturing operation and decamped to the Rouge plant, the city remained the world headquarters of Chrysler, founded in Highland Park in 1925.

Ford’s Highland Park plant, ca. 1920

By the early nineties, though, Chrysler chair Lee Iacocca had announced that the company would be moving to Auburn Hills, some fifty miles north of the city. With the departure of those final five thousand Chrysler employees, Highland Park lost a quarter of its tax base and 80 percent of its annual budget. Having spurned Detroit’s advances during Ford’s heyday, Highland Park now stood abandoned by its onetime corporate suitors for younger, prettier suburbs. There was occasionally talk of Detroit absorbing Highland Park, but that was just wishful thinking, Detroit at this point having zero interest in adding more crime, blight, and desperately poor people to its own mean buffet of urban pathologies.

Today, driving north on Woodward Avenue, you’d never notice having crossed from one city to the other. You pass a combination fish market and takeout restaurant (“U Buy, We Fry”), and the Gold Nugget Pawn Shop, and Mo’ Money Tax Returns, and a Babes N Braids, and a place called Cherokee’s Hot Spot where you can get your ears or nose pierced or pick up some exotic dance wear (“Plus Sizes Available,” notes a sign in the window), alongside numerous other long-shuttered apartment complexes, municipal buildings, and storefronts (including the rubble of a florist).

Yet Highland Park, officially the poorest city in Michigan, manages to tidily pack all of the problems of Detroit into just three square miles. In fact, fantastic as it might seem, the city is actually in much worse shape than Detroit proper, the one place Detroiters can gaze upon and say, “Man, those guys are fucked!” One afternoon, wandering around Highland Park, I must have accidentally stepped back over the border, because when I asked an older gentleman raking his lawn about Highland Park’s city services, he appeared deeply offended. “This is Detroit,” he snapped. “I don’t know anything about Highland Park. I don’t go over there.” We were two blocks away.

In other words, Highland Park is the Detroit of Detroit. In 2011, the Bing administration floated the possibility of closing eighteen of the city’s twenty-three public library branches; Highland Park’s entire library system has been closed since 2002. Detroit has shed more than half its population since the 1950s; Highland Park, over the same period, has lost four-fifths of its citizens. In Detroit, the street-lights are notoriously spotty, and there has been discussion of reducing their number by nearly half; Highland Park owed so much money to the electric company that it agreed to entirely decommission all lights on residential streets—which meant not only switching them off but physically removing the posts. (Residents have been asked by city officials to leave on their own porch lights as crime-prevention measures.) Detroit’s police force remains woefully understaffed; Highland Park fired its entire police department in 2001, outsourcing patrols to the Wayne County Sheriff’s Department. Since its revival in 2007, the Highland Park PD has been headquartered in a mini-station at a strip mall, where the jail is a makeshift chain-link cage.

When I visited the Reverend David Bullock, head of the Highland Park chapter of the NAACP and pastor of Greater St. Matthew Baptist Church, he told me, “I always say to people, ‘You want to see what Detroit’s going to look like when the auto industry leaves? Come to Highland Park.’ It’s Detroit writ small.”

* * *

One day, my brother Paul called to tell me about one of his coworkers at Children’s Village, the juvenile detention center where he worked as a therapist. This parlicular colleague, Marvin Vaughn, held a staff position; his duties ranged from moderating group activities to restraining kids who became violent. The name Children’s Village took on a more sinister shading when you realized certain of the villagers had been accused of stomping random homeless guys to death or shooting people during violent carjackings. (Paul wasn’t allowed to talk about his clients, but the highest-profile cases always turned up in the papers.) Marvin, meanwhile, had a second job, in Highland Park, where, in addition to his full-time position at Children’s Village, he moonlighted another thirty hours each week as a firefighter.

Marvin would often drive straight from Children’s Village to Highland Park and spend the night at the firehouse. (Those overnight hours were billable, which was how he managed to work seventy-hour weeks.) Per capita, Highland Park had an insanely busy engine house, averaging 150 fires each year: apartments, party stores, vacant homes, most probably arson, though this was always tricky to prove. When Paul told Marvin about my book, he suggested I swing by on Angel’s Night.

I headed over to Highland Park around eight. It was unseasonably humid for a late October evening, nearly seventy degrees. On Oakland Avenue, I passed a couple of citizen patrollers in a gray Cadillac creeping along in the left lane at well below the speed limit. A yellow light, the sort an undercover detective in a seventies cop show would attach to his unmarked car if he needed to give sudden chase, flashed from their roof, its languid blink rate having seemingly been set to match the speed of the vehicle. It looked like the lead car in a funeral procession, if everyone else who might’ve attended the funeral had also met unexpected and horrible ends.

Marvin had given me directions to the firehouse earlier in the day, but we’d had a bad phone connection and I assumed I’d misheard the address, because the only thing in the vicinity appeared to be an industrial park of cheap prefabricated warehouses. After circling for twenty minutes, I finally called Marvin back, and he told me to drive into the park, the former site of Chrysler’s world headquarters. Following a circuitous road past nondescript auto-parts factories (Magna Seating, Johnson Controls), I reached the edge of a cracked, weed-strewn parking lot, where I spotted a tiny blue sign reading Fire Department. On the far side of the lot, bordering a set of train tracks, an unmarked warehouse building stood, so anonymous and isolated you’d think it housed toxic waste material or a fleet of garbage trucks. A tall, full-figured guy wearing a Highland Park Fire Department sweatshirt emerged from a side door and waved me over.

You could see how Marvin’s size would intimidate a misbehaving juvenile offender, but everything else about him exuded a laid-back, almost goofy affability. Marvin had grown up quite poor in Picayune, Mississippi, before his dad, following a well-trod African American migratory pattern, landed a job with Pontiac and moved the family to the metropolitan Detroit city of the same name. Marvin was in his midthirties, married, no kids yet, though his wife wanted some. There was a throat-clearing quality to his way of speaking that made it sound like at any moment he might suddenly burst into a raspy chuckle, and his voice darted up a couple of octaves whenever he became excited. Tonight, he wore a pair of thick-armed glasses that looked like they should be tinted. He also had a single patch of gray hair near the middle of his head, about the size of a large birthmark.

A dirty secret of union towns like Detroit was how the historic battle for fair overtime pay, combined with the shrinking of benefits and real wages, had resulted in the strange phenomenon whereby, in the midst of deliriously high unemployment, the lucky people who’d somehow managed to hang on to their jobs might actually wind up overemployed, either via copious overtime—this worked out well for management, as overtime remained cheaper than covering the benefits of an entirely new hire—or, as in Marvin’s case, snagging second, lower-paying jobs, simply to maintain something approaching the middle-class lifestyle to which they’d grown accustomed.

Marvin led me around back, through the wide-open bay doors. The Highland Park Fire Department, it turned out, was being housed—stored?—inside a warehouse. Marvin explained that the department’s poorly maintained former headquarters had been declared an environmental hazard by OSHA, so they’d come to occupy this temporary location. That was six years ago. Past a row of aged fire trucks, a white McDonald Modular Solutions trailer had been set up as an office. In front of it, an old stuffed couch and a pair of recliners, all scavenged from various curbs by the firefighters, had been arranged around a television set. A rack of oxygen tanks lined one of the walls like bottles of wine. Next to the trucks, the rest of the uniforms stood at the ready: boots on the ground, with thick, flame-retardant pants and suspenders already attached, so the firefighters could step right into their pant legs and yank up their suspenders with a single motion. The prepared uniforms drooped down over the boots like melted fire-man candles.

Firefighters milled in the dim light, chatting and eating. The ceiling of the warehouse rose nearly two floors above us. In a distant corner, I could make out a gym consisting of free weights and benches people had brought from home or picked up at garage sales. It had been a quiet night so far. Nearby, a blue plastic barrel with a handwritten sign taped to it read

POP

CAN$

Beverage cans in Michigan were returnable for deposits.

The firefighters had actually been evicted from their old firehouse while Highland Park’s finances were being controlled by the state of Michigan, under the auspices of an emergency manager. Rather than bring the old firehouse up to code or build a new one, the city had been paying several thousand dollars per month to heat the cavernous space each subsequent winter. Thanks to a proposal written by one of the department’s junior firefighters—on his own time and initiative, with no grant-writing training3—Highland Park received a $2.6 million federal FEMA grant for a new building. But after two years, the grant money still hadn’t been spent. Officials blamed the historic designation of the old firehouse, which made it difficult to tear down, though sources inside the department ascribed the delay to political infighting and shadier efforts to funnel the grant money to other city projects. Questions have also been raised about the way in which the architectural firm that contracted to design the new firehouse won its bid.

In the meantime, the firefighters had made do. “We call this the Village,” Marvin said, leading me to the back of the warehouse. “One guy came up with this idea, because the trailer doesn’t hold us all.” In a dark corner, the firefighters had nailed together planks of raw plywood, constructing a multilevel warren of individual cells, a cross between a children’s box fort and the sort of slapdash partition undergraduate roommates might throw up in a dorm. They’d built twenty-six rooms in all; a Jolly Roger flag hung from the roof. Two of the firefighters, apparently preferring al fresco accommodations, slept in tents. Marvin pushed open the door to his room.

“It’s small, but everyone’s got their own humble abode,” he said. The space was about the size of a large walk-in closet, with barely enough room for a twin bed and a television set. A framed photograph of a fierce-looking house fire hung next to the TV.

“Were you there?” I asked.

Marvin nodded and said, “It’s the fire devil holding on to the house—see it?” He stabbed the flames jutting from the roof with a thick finger. Sure enough, they resembled a cartoonish demon’s head, and you could even flesh out the pair of fiery arms reaching down to hug either wall of the place. “It’s not cropped or anything,” Marvin said.

Marvin had started out as a firefighter in Pontiac. “Before that, I was a junior engineer,” he said. “Sucked! I tried nursing. Sucked! I said, ‘I need something exciting.’” Eventually, a friend told him, “You want to see some real fires? Come down to Highland Park.” At the time, Republican governor John Engler had just modified the residency rules in Michigan, allowing city workers to live outside the community employing them, so Marvin was able to transfer to Highland Park without moving there. None of the Highland Park firefighters I met actually lived in the city, except when they slept at the warehouse.

An average night found eight firefighters on duty. Normally, this level of staffing would be more than adequate for a city of Highland Park’s size. But considering the firehouse often saw multiple structure blazes over the course of a single evening, the place eked out its defensive duties with an absurdly skeletal crew. One of Marvin’s lieutenants, Eric Hollowell, told me about a time when eleven houses burned in one night. Hollowell’s entire seven-person unit—one of the eight firefighters on duty must always remain behind to answer incoming calls—had been in the midst of combating the first three fires, a trio of neighboring houses, when they got word of several more fires breaking out at the opposite end of the block, forcing Hollowell to split up his already overstretched crew. (Normal procedure would call for three trucks—about fifteen people—when responding to a single residential fire.) Not long after that, a resident approached Hollowell at the scene and informed him of another abandoned house that had caught fire, on the next block over. Hollowell had to let that one free-burn for an hour. He couldn’t spare any more guys.

One of the fire trucks came from Texas, used; another, also used, from Arizona or Georgia, no one could remember which. All were ancient by fire engine standards, twenty years old, leaky. One had a five-hundred-gallon tank that, by the end of an average night, would lose three-fifths of its water; another’s ladder, so rickety, had everyone afraid to climb it.

“You know how we communicate at fire scenes?” Hollowell asked me.

A part-timer named Chuck, sitting nearby, glanced up and muttered, “You telling him everything?”

Hollowell continued, “We only have three radios. We communicate by voice. Once people are inside a building, I have no way to know if they’re okay. Chuck is driving our main truck and he doesn’t have a radio. If people are called to another scene, he can’t communicate.”

Chuck, nodding glumly, admitted, “It’s like in baseball: all hand signals.”

Then he did an imitation of a catcher flashing dispatches to the mound.

* * *

Angel’s Night had been slow, so Marvin invited me to come back to the station on another occasion. Even by Highland Park standards, the week of my return had been a rough one. A two-hundred-unit apartment complex had burned several days earlier, one of the residents dying after leaping from a second-story window. “Definitely arson,” a firefighter who wished to remain anonymous told me. “Either an insurance job or some kind of retaliation.”

When I showed up, several of the men had arranged their folding chairs in the mouth of the bay doors, facing the train tracks. They all looked crispy and adrenaline-deprived. Even Marvin, outwardly jovial as ever, had exhausted, vacant eyes. The night before, there had been only two fires, but afterwards, Marvin hadn’t been able to fall back asleep. “Every time gas prices drop, we see an increase in fires,” he noted. A Bluetooth device blinked from one of his ears. He delivered the line matter-of-factly, like an observational comic doing a bit about airplane food.

Hollowell sat nearby, chain-smoking and drinking coffee from a thermos. A trim black man with a cleanly shaved head and a wispy mustache, he wore a blue Highland Park Fire Department polo shirt tucked into dark slacks. Hollowell was thirty-seven. He’d grown up in Highland Park, just a few blocks from the warehouse; so few houses remained on Hollowell’s old street, one of his coworkers told me, “I call that block We Lost It.” Hollowell’s mother had been a teacher at Highland Park High. His father died when Hollowell was only ten years old. An electrician, he’d been doing work in a friend’s basement as a favor and stepped into a puddle of water, not realizing someone had cut the power back on.

Hollowell had always thought being a cop would be a cool job, that or the military, and began working as a cadet-in-training at the police department when he was fifteen. By the time he turned twenty-one, he’d already seen close to thirty homicides. The job started to get to him. He’d been fired upon by people openly selling drugs from their porches, and he took to strapping on his gun before going out to cut the lawn.

“Actually, if I was outside at all,” he emended. “I could be sitting on my porch and I’d have a gun on the table next to me with a rag over it. The city was riddled with dope.”

Hollowell related all of the above in a muted deadpan. I’d be tempted to describe his affect as hard-boiled if not for his habit of coaxing reactions from his listener by pulling some manner of exaggerated face.

A train flew by. Hollowell lifted his hand and waved at the conductor. He told me he’d transferred to the engine house as soon as word of an opening came down.

Hollowell’s colleague Sergeant Nate Irwin wandered outside and planted himself in another chair, bringing his cigarette and coffee mug. Hollowell told Irwin about my book.

Irwin gave me an appraising look. “You going fiction or nonfiction?” he asked.

Non, I said.

He snorted. “No one’s gonna believe it.”

Hollowell and Irwin could be characters in an eighties Hollywood buddy movie about firemen. Irwin, a thirty-two-year-old white guy, had grown up in Royal Oak, which, back when I was a kid, had been the “hip” suburb (record stores, vintage shops, a bondage outfitter). His head, shaved cleaner than a brush cut, retained a sandpapery stubble, and Irwin clearly derived therapeutic pleasure from pensively rubbing it while discussing the particular hardships of his career path. Having worked in Highland Park for over ten years, he’d armored himself with a jaded air similar to Hollowell’s.

“How did I end up here?” he asked. “Well, you watch the news.” He meant that, like Marvin, he’d been drawn by the action. “And then,” he said, lighting another cigarette, “after a few years, you can’t leave, for multiple reasons: (a) you don’t want to, and (b) no one will take you.” The reason for (b), oddly enough, had to do with the amount of field action one quickly accumulated in a place like Highland Park: a captain at a suburban department, who might see a handful of fires each year, wouldn’t necessarily be eager to hire a young guy with so much more experience.

Highland Park and Detroit get so many fires, of such spectacular variety, that firefighters from around the country—Boston, Compton, Washington, D.C.—make pilgrimages here. Some monitor the police scanners and just turn up at the scene, snapping photos and shooting video. A decent enough photograph might make the pages of one of the trade (Fire Chief or Firehouse), where a cover shot could fetch a thousand bucks. “We’re YouTube legends now,” Irwin noted wryly. One firefighter from the Bronx visited twice every year. He’d told the Highland Park guys the Bronx had become boring. Most of their buildings were occupied now, and it just wasn’t popping like in the old days.

The sky had turned a mauve color. On the service road of the industrial park, a stream of cars began to depart; a late shift at one of the parts shops must have ended. From inside the warehouse, we could hear the echo of a television commercial for Liberty Mutual Insurance. What’s your policy? the announcer asked. A slight, pleasant breeze stirred up.

“It’s probably something free-burning somewhere, sucking up all the oxygen,” Hollowell said.

A firefighter named Chaplain sat nearby, occasionally answering a phone and taking notes on a pad. I hadn’t paid much attention to him until I realized he was talking to someone who seemed to be requesting an ambulance. Hollowell noticed the curious look on my face and said, “This is our 911.” He meant that Chaplain—a lone guy sitting in a folding chair answering a phone—was the 911 operator for the entire city of Highland Park. When the call was completed, Hollowell said, “Chaplain, who have you got tonight waiting for the EMS?” Chaplain looked at his pad and said, “Two strokes, a heart attack, a guy who fell and cracked his head open.” He said the first call had come at 5:56 p.m. and none had received EMS attention yet. I looked at my watch. It was after eight.

The city of Highland Park did not own an ambulance and had only one EMS truck. Many of the calls Chaplain had been fielding were repeat calls from people asking when the medics would arrive.

With the exception of Hollowell and Irwin, the other firefighters sitting out there—the diminutive, shaved-headed white guy who talked about his impoverished childhood, how when his mom got remarried, the family finally had enough money to buy Kool-Aid; the ripped Iraq vet, with tattoos of a machine gun and Arabic script running up and down his arms, who used to live in Detroit, but had moved across 8 Mile, to suburban Ferndale, “just to get city services,” he said, adding, “I mean, my fiancée is pretty tough. She can handle herself. But if you get someone on your front lawn acting crazy and you have to shoot ’em, that’s no good”—all of these guys were being paid ten dollars an hour. Cops in Highland Park started at eight. Irwin and Hollowell both liked to use this fact to wind up their right-leaning chief, especially when it came to conservative demagoguing on the supposed overcompensation of the public workforce.4

“Unions, I mean, what’s left?” Irwin asked. “The trades? None of those guys even have jobs. The only unions left are the ones they can’t break: public safety, UAW, Teamsters, teachers.”

Public safety officers in Highland Park were no longer unionized, which was how the city got away with compensating the cops and firefighters so pathetically. As with corporate structured bankruptcies, the city had been able to break its existing union contracts when, facing a $6.5 million deficit, the first emergency financial manager, Ramona Henderson-Pearson, took over the city’s finances in 2001. A disastrous attempt by Henderson-Pearson and then-mayor Titus McClary to build a new suburban-style development within Highland Park was later investigated by the FBI.5 Henderson-Pearson’s successor, Arthur Blackwell II, was convicted of illegally paying himself a salary of close to $300,000 while serving as manager. Blackwell’s successor, Robert Mason, was not convicted of any wrongdoing—though, to be fair to his predecessors, he served only for three months.

* * *

Why were there so many fires in Highland Park? The high number of vacant houses, along with squatters and legitimate residents who pilfered electricity via jerry-rigged, easily combustible wiring jobs, pushed up the count, for sure. But Irwin considered most of their runs the result of arson. You could quick-claim a deed to a house in Highland Park for a thousand dollars and insure it for eighty thousand. If the house burned a month later, suspicious or not, it would be one fire among many, and best of luck proving anything, because until recently Highland Park had no fire inspector. Irwin had paid out of pocket to take investigatory courses at the fire academy. He’d also bought his own equipment.

Hollowell said, “Mark, he probably doesn’t want to tell you this, but I’m going to: getting a license on your own like that is totally unheard of. Up until this point, fires were just not investigated in this city, at all.”

Irwin, seeming embarrassed by the attention, leaned down to adjust the volume of a walkie-talkie next to his chair. “I have a hard time sitting around,” he murmured. “I was just looking to do stuff.”

“For fifteen years here, the fires have gone completely unchecked,” Hollowell went on. “The city played games as if they were being investigated, but they didn’t really do anything.” Hollowell was convinced that the eleven-fire night hadn’t been a fluke, that one of the arsonists had started the latter fires to taunt the firefighters.

Irwin, who was sitting with his legs crossed and black boots unzipped, finally warmed to the topic. “Investigating sucks,” he said. “Only 1 to 2 percent of arson cases end in prosecution, nationally. It’s so difficult to prove. You’re looking at all circumstantial facts. Before you even get into court, the DA is going to try to prove you’re not qualified.” He smiled. “The good thing about Highland Park is, that’s hard to do, because we have lots of experience. But basically, if you can lie you can get away with arson. You know the foam in furniture, like a couch from Ikea, is made of low-grade petroleum. So if you can put your space heater next to your couch, it’s as good as or better than gasoline. And I can’t prove it was intentional. You’d pass a lie detector test. Not that I have a polygraph machine. Nor am I allowed to interrogate people. But every single case I get has accelerants, so there’s not a problem proving incendiary. The problem is proving who did it. So I just keep trying and trying, hoping to find a fingerprint on a gas can one day.” He smiled ruefully at his own Willy Loman impression. After a moment, the smile vanished and he added, “It gets depressing.”

* * *

Another night, after most of the firefighters had drifted off to the Village, I was left alone to doze off in front of the television. A young firefighter I’d never seen before lay sprawled on the striped couch closest to the fan. I wondered why he hadn’t gone to his room, and then we started chatting and I found out he was a volunteer. Having recently completed his fire training, the guy—I’ll call him Donnie—was looking for a job, and so a few times a month he’d work a shift as a volunteer, hoping to make his presence known and increase his likelihood of being hired if a paying position opened up. I hadn’t realized you could work an unpaid internship at a job requiring you to risk your life.

Donnie kept turning his head to one side when he talked to me, finally revealing that he was partly deaf in his left ear, on account of being carjacked. He said he’d been very stupid: he’d stopped for gas after dark. (In certain parts of Detroit, this qualified as “asking for it.”) He’d seen the carjackers approaching and hadn’t tried to resist, but one of the guys pistol-whipped him anyway and the gun had gone off near his ear, permanently damaging his hearing.

Donnie also told me that he was taking classes at Wayne State, that he thought Medicaid should fund abortions and that people on welfare shouldn’t be allowed to have kids.

I said, “Huh.”

Donnie said, “I might sound like an extremist, but that’s the way I feel.” Then he complained about how the downtown riverwalk, late at night, had become rowdy—how there were too many “ethnic” people there, if I knew what he meant. I was pretty sure he meant black people. If it had been another white guy saying this to me, I would have felt obligated to keep my face very still and not seem like I was agreeing with any racist insinuations. In the case of Donnie, though, I nodded ambiguously, almost imperceptibly, in a way that might lead one to believe I’d merely started to nod off, considering the lateness of the hour.

* * *

Hollowell told me I could ride along with him if a call came in. One evening, close to midnight, the alarm sounded. This time, I was alone on the couch, reading. Then I blinked and everyone was wide awake and suited up. Marvin, on dispatch, took the call. His voice came over an intercom, sounding disconcertingly serious.

“All apparatus respond to 40 Pasadena house fire,” he said. “Police department is on the scene.”

Irwin frowned. There’d been a fire on Pasadena the night before, directly across the street. Irwin thought someone must have gotten the address wrong—that, surely, the same house must have lit up again.

Hollowell and I climbed into his engine. “Sounds like a good fire,” he said. Oxygen tanks set into the front seats forced me to sit forward in an awkward manner. The instrument panel was covered in dust and looked very old, like technology from another era. Different buttons that could light up read “Left Scene Light,” “Right Scene Light,” and “Retarder Applied.” An axe with a yellow handle leaned between our seats like a manual gear shift.

Blasting his siren, Hollowell raced to Oakland, leading a three-truck convoy. We took a dramatically wide turn onto Woodward, hurtling down the center of the street, and I felt a boyish thrill. Hollowell had a sober look on his face.

When we turned onto Pasadena, I could see flames strobing from the porch of a brick duplex. As we got closer, though, it became clear that the home itself wasn’t ablaze. Someone living inside had, inexplicably, started a fire in an oil drum on the covered porch—a wooden porch, so doubly foolish. The flames were practically tickling the underside of the eaves. Still, it wasn’t a three-alarm call. As we exited the fire truck, one of the police officers, a blond woman, approached Hollowell apologetically. “When we rolled up, there were flames all the way up to the roof,” she insisted.

The man who’d started the fire, wiry, in a white undershirt, appeared inebriated. He insisted he’d been burning wood to keep away bugs. When the police officers ordered him to extinguish the fire, he’d disappeared into the house, emerging with a single ice cube tray sloppily filled with water. Hollowell asked the man for his name. He grimaced and said, “She took it,” nodding dismissively at one of the officers, before retreating inside to fetch more water.

The other firefighters were already beginning to climb back into their trucks. I looked across the street at the remains of the previous night’s fire: a decent-sized brick home, its arched roof now partially collapsed.

Back in the truck, Hollowell grumbled about having been summoned for such a nonsense run. “The address on the guy’s license was in Detroit—Burn Street!” he said, appreciating the irony on some level but not laughing. On the way back to the warehouse, we passed an old firehouse on Stordivan dating back from when Highland Park had three stations. That particular station place had been shut years ago and since horribly burned. Hollowell said the fire had happened when a man from Inkster who’d murdered his mother had carried her corpse to the empty station and torched it.

At the warehouse, Irwin said he thought there might be a connection between that night’s episode and the fire across the street. But Hollowell shook his head. “I think that guy was just stupid. And high. He’ll start up that porch fire again as soon as the police leave.”

Hollowell’s mood had soured. A few years ago, he’d moved out of Highland Park to a suburb north of 26 Mile. When I asked him what could be done with the city, he gave me a look and said, “Honestly? Level it. Tear it down and start over.”

Marvin came out of his room to hear about the nonfire. When they told him the guy said he had just been trying to keep away bugs, Marvin said, “Well, in Picayune, Mississippi, you do burn wood to keep away the bugs.”

“This isn’t Picayune, Mississippi,” Hollowell said.

Marvin said, “No, it’s not.”

1 The plot was eventually leveled when development truly got under way, so today the area is no higher than anywhere else in Detroit.

2 In Highland Park, Ford not only perfected his notion of the assembly line—the number of Model T’s produced annually at the plant soared from 82,000 to two million in the course of a decade—but also announced the doubling of his workers’ daily wages to an unheard of five dollars. John Reed, the radical journalist and future author of Ten Days That Shook the World, wrote after his visit to Highland Park, “The Ford car is a wonderful thing, but the Ford plant is a miracle. Hundreds of parts, made in vast quantities at incredible speed, flow toward one point. The final assembly is the most miraculous thing of all.” In Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, Year Zero of the AF (After Ford) calendar aligns with the year the first Model T rolled off the Highland Park assembly line. “Like the New Testament story of the loaves and fishes,” writes Ford biographer Steven Watts, “Ford seemed to be creating material sustenance for thousands of people by a superhuman process. His fellow citizens responded with a kind of worship … ”

3 Beyond some assistance from his sister, a high school English teacher in rural Clio, who helped edit the narrative portion of the proposal.

4 The first time I visited the Highland Park engine house, they’d just had a benefit for a part-time firefighter who almost died when he’d been overwhelmed by flames while putting out a fire in a vacant house. “His hands, for all practical purposes, are gone,” one of his colleagues told me. “That’s for a guy who makes ten bucks an hour, no benefits.”

5 The neighborhood, called North Pointe Village, remains one of the eeriest in Highland Park, a miniature ghost town composed of 150 brand-new two-floor colonials with cheap-looking gray siding, most standing vacant and gutted, some partially burned. The majority of the homes had never even been occupied. They were so cheaply built, their basements almost immediately began leaking ground and sewage water, and certificates of occupancy couldn’t be issued by the city. The developer sued the building contractor, who filed for bankruptcy; a group of backers in California who’d bought the homes as investment properties in turn sued the developer, who also filed for bankruptcy.