Former Detroit mayor Kwame Kilpatrick, handcuffed in court after violating the terms of his probation. [Daniel Mears/ Detroit News]

POLITICS

THE QUESTION PERSISTED, as yet unresolved: was Dave Bing really the man we wanted behind the wheel of the car metaphor representing Detroit’s future? As the nationwide sense of economic doom was hitting Michigan harder than any other state of the union, Detroit not only faced bankruptcy but the threat of a state takeover, made possible by Governor Snyder’s emergency management law, dangling like an invisible sword. Was it real, or just that, a threat, meant to stiffen the spines of Detroit’s historically feckless political class in their forced marched toward austerity?

Detroit’s tawdry and dispiriting political erosion had started at the top, with the undoing of Kwame Kilpatrick, the young, virtuosic, wildly charismatic mayor who’d come into office in 2002 on a wave of promise and left in handcuffs, charged with perjury and obstruction of justice. While Kilpatrick and his administration also stood accused of bribery, kickbacks, embezzlement, blatant cronyism, and running the city like mafia capos, his ultimate downfall proved to be a humiliating sex scandal involving his chief of staff—and most damningly, his agreement to settle a police whistle-blower lawsuit with nearly nine million dollars of taxpayer money in order to prevent a series of suggestive text messages from seeing the light of day. That ploy obviously failed, and so the public was eventually treated to ripe exchanges such as the following:

CB (Christine Beatty, the mayor’s chief of staff): I really wanted to give you some good head this morning and i didn’t know how to ask you to let me do it. I have wanted to since friday

KK: Next time, just tell me to sit down, shut up and do your thing!

Meanwhile, several members of Detroit’s city council managed the improbable concurrent feat of almost equally disgraceful public misbehavior, including mockery of a fellow councilperson’s hearing aid (Council President Monica Conyers), involvement in a bar fight with another woman (ditto), threatening to “get a gun if she had to” in order to shoot a mayoral staffer (ditto), skipping important votes to tour in England while casually referring to the council in the UK press as “a second job I have” (ex–Motown star Martha Reeves), and paying an annual sixty-eight dollars in property taxes for years without once questioning the preposterously low, clearly erroneous bill (JoAnn Watson, who insisted the charge had simply led her to “the natural conclusion my house isn’t worth much anymore”).

In a plot twist too delicious for fiction, Conyers, the wife of long-serving and belovedly liberal Representative John Conyers, eventually pled guilty to a bribery case involving a billion-dollar sewage sludge disposal contract. As of this writing, she is serving a thirty-seven-month prison term. When news of the FBI’s investigation into the sewage deal broke, Reeves, asked for comment, claimed to identify a net positive. What she said, exactly, was: “What I think it will do is get a bit more publicity for the council. This is one of the most highly publicized councils in the history of Detroit. They say if you’re not doing anything, they’re not saying anything about you.”

The writer Zev Chafets, in Devil’s Night, his 1991 book about Detroit, compared the city to a postcolonial African state, despoiled by attendant historical baggage and endemic corruption. It’s sort of a great analogy, but also a flawed one. Black Detroiters were not a conquered people; they moved to Detroit to improve their lives—and did, building the city alongside the white majority, albeit in drastically disadvantaged and prejudicial circumstances. To me, the power shift in Detroit, and the ensuing hostilities with the suburbs, feels much closer to a cold war satellite-state scenario, in which dueling ideologies play themselves out through largely immaterial pawns. And so in the seventies and eighties, Coleman Young was spoken of by suburbanites in terms reserved, at a national level, for the likes of Fidel Castro or Ayatollah Khomeini. At the invocation of Young’s name, many suburbanites easily lapsed into the fanaticism of the anti-Castro Cubans raging from the shores of Miami Beach at the not-so-distant island paradise snatched from them, the rightful owners, by a corrupt demagoguing madman.1

Likewise, for all his outsized flaws, Kilpatrick clearly did himself no favors by being African American and built like a linebacker. Putting his blackness aside, Kilpatrick would have still been a flamboyant, almost Shakespearean character in many ways, but certainly his penchant for wearing diamond-studded earrings and flashy suits and listening to hip-hop abetted his transformation into a cartoonish bogeyman. There was a slightly creepy, Willie Horton aspect to the way the camera lingered on his mug shot on local newscasts and the ease with which it became de rigueur for (generally white) commentators to describe him as a “thug.” While still mayor, at the height of the scandals assailing his administration, Kilpatrick made an infamous state of the city address in which he claimed, “In the past thirty days, I’ve been called a nigger more than any time in my life.” Using such inflammatory language so opportunistically, and in so public a forum, drove his critics and even many of his few remaining supporters apoplectic—and yet the pointed, incessant deployment of “thug” as descriptor suggested that perhaps he wasn’t exaggerating all that much.

After Kilpatrick’s resignation, the president of the city council, Ken Cockrel Jr.—whose late, aggressively Afroed father, a radical civil rights attorney, had served on the council in the seventies as an openly Marxist candidate—automatically became mayor. Prior to his ascension, the bald and somewhat hulking (but quite genial) Cockrel had become an unintentional YouTube sensation thanks to clips of a city council meeting in which Monica Conyers seemed to violate parliamentary procedure by shouting “You not my daddy!” at Cockrel before angrily referring to him as “Shrek.”

Cockrel’s reign was short. Within a few months, a special election was held, giving the business community the opportunity to install one of their own, Dave Bing, who had parlayed his NBA stardom into the creation of a successful steel- and auto-parts-supply company. Coming after Kilpatrick, the anointment of the former Detroit Pistons point guard made perfect sense. Bing was the anti-Kwame, a lanky, graying man in his late sixties, bespectacled and mild-mannered. Critics pointed out that Bing had not lived in the city proper for decades, having long ago decamped to the tony suburb of Franklin. But voters didn’t care. Bing cut a perfect visual contrast to the gross appetites of the Kilpatrick administration, which had remained on public display for so long. There was an appealing, ascetic quality to the new mayor—something monkish about his gauntness, his quiet dignity, his unself-conscious baldness and drooping silver mustache. He looked like an avuncular praying mantis. Even his eye-glazing ineptitude at public speaking became a plus when compared with the glibness of his quick-tongued predecessor. This guy was not going to cause trouble; this guy wouldn’t be capable of tricking us. Detroit no longer wanted a visionary—just a ruthlessly competent technocrat in the mold of Michael Bloomberg, someone whose very lack of charisma would be its own mark of authenticity.

* * *

With Bing firmly in place, political observers turned their attention to the city council, a governing body that historically had a contentious relationship with the mayor of Detroit. Considering Bing’s age and his vow to serve for a single term, the council might also be the place where the next mayor emerged, a man or woman with the boldness to steer Detroit through this uncharted, transformational moment—once noble, self-sacrificing Bing had taken the hits for implementing tough new policies in the name of rightsizing and budgetary rectitude. The 2009 elections looked to be an exciting race. By summer, 167 candidates had thrown their hats into the primary, all jockeying for only nine seats, and the scandal-weary Detroit electorate seemed prepared to usher in a new slate of leaders: the postprimary field, whittled down to eighteen, had shed both Monica Conyers and Martha Reeves.

One evening that October, I attended the closing candidate debate, which was being held at the grand, domed Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. Because of their potentially unruly number, the candidates had agreed to multiple, subdivided debates featuring randomly selected participants, so this final meeting would involve only six of the contenders. Still, it was being closely watched because it featured the two front-runners, Charles Pugh, a former TV news personality who also happened to be openly gay, and Gary Brown, an ousted police officer whose whistle-blowing lawsuit had set off the chain of revelations ending with the toppling of Kilpatrick. Pugh’s popularity, in particular, was considered surprising, as conventional wisdom had pegged Detroit’s predominantly black electorate as socially conservative when it came to issues like homosexuality.

Both men, though, came bearing, “uniquely Detroit” (Pugh’s words) backstories. In 1974, when Pugh was three years old, his mother was murdered by her heroin-dealing boyfriend; four years later, his father, depressed after being laid off from Ford, killed himself. Pugh, aged seven and the only other person in the house at the time, discovered the body. Somehow, he not only survived but flourished. Raised by his grandmother, Pugh decided to go to journalism school, with the intention—he mapped out this plan in high school—of starting in local news, moving onto a national broadcast like The Today Show, and eventually running for the U.S. Senate. The years of television experience had given Pugh a distinct messaging advantage over most of his opponents. A young-looking thirty-eight-year-old with a highly personable, perpetually empathetic demeanor, Pugh addressed potential constituents with a warm and expertly calibrated sincerity. He had the broadcaster’s habit of smiling as he spoke and took an almost childish delight in the pronunciation of every word, as if, rather than speaking, he were nibbling a treat or unwrapping a series of little presents with his mouth.

Meanwhile, Brown, a methodical-minded overachiever, had known he wanted to be a cop by the time he was twelve. By sixteen, he’d finished high school, though before graduating he’d already enrolled in after-school community college courses in criminal justice. On the advice of one of his professors, a judge, he joined the Marine Corps rather than head straight for the police academy, where he was too young to become a cop, anyway. After being stationed at Pearl Harbor, he returned home to Detroit to find his twin brother had become addicted to heroin. Brown, in turn, became an undercover narcotics officer. “I thought this was a way of helping him,” Brown told me. “I’ve raided every drug house in the city. I guess it was me being idealistic.” Brown, who helped build complex conspiracy cases against drug gangs like Young Boys Inc. and the Chambers Brothers, would call his brother before certain raids to make sure he wasn’t in the targeted dope house. As for his eventual clash with Kilpatrick, there was an almost literary perfection to the asymmetry between the two men, it seeming especially poetic for the ostentatious Goliath of a former mayor to be brought low by someone as unassuming, at least at first glance, as Brown. A trim, preppy guy with glasses, a neat little mustache, and the high, purring voice of a chain-smoking grandmother, Brown was basically Eliot Ness, exuding both military discipline and an upright fixation on investigatory precision.

The auditorium for the debate was packed. I sat beside an unusually tall man wearing an expensive gray suit and a gold Fendi watch. He told me he tried to attend most of the debates in order to stay involved, though he was more of an Eisenhower Republican. Introducing himself as a lawyer “by trade,” he said he hoped to one day produce his own low-budget, self-financed movies for a black audience. He also thought one of the keys to Detroit’s revival might lie in its rich cultural history, in somehow pivoting on the world’s consistent adoration of the Motown sound, and of Detroit artists like Aretha and Eminem, by cultivating a vibrant club district. “New Orleans has a six-block entertainment strip and it attracts two million people a year,” my neighbor said. He understood the job would not be easy. His brother, he said, liked to tell a story about leading a blind man into the light. What’s the first thing he does? his brother asked. Close his eyes.

I didn’t entirely understand the fable. Detroit was, presumably, meant to be the blind man, recoiling from too much change, even change of a positive nature. But had the blind man actually regained his sight? Or was the point that even his blind eyes were sensitive to bright new surroundings? The lawyer, after delivering the punch line, gave me a gnomic grin. I smiled back and nodded foolishly, as if we’d shared a moment of wisdom. After that, I didn’t feel like I could ask what he’d actually meant.

Soon the six candidates filed onstage. Part of the drama of the debate, aside from its finality, surrounded Charles Pugh, who had been forced, just the day before, to make a humiliating disclosure: his $385,000 downtown condominium was about to be foreclosed on, after his default on a second mortgage. Apparently, Pugh was also being sued by his condo association for unpaid dues. As a broadcast personality, Pugh made well over $200,000, a year, but he claimed that leaving his job in order to run for city council full-time had put him in financial jeopardy—a claim undermined when the Detroit News reported on the eleven different eviction notices Pugh had received while renting an earlier apartment during a four-year period beginning in 2001. In an effort at damage control, Pugh posted a video on his website. It appeared to have been hastily produced with a cheap webcam. Pugh’s large and uncannily egg-shaped head—which, completely shaved, made him look like a colossal baby—had been shot at an unflattering angle and nearly filled the screen as he exhorted viewers to pray for him and vowed to remain “on the grind, asking for your vote.” He also insisted that going into foreclosure actually opened a number of “options” for the foreclosee—true, in a sense, if those options were limited to (a) leaving your house or (b) paying back the money you owed.

In his introductory remarks, Pugh assumed an upbeat tone, as if he were anchoring live from a Super Bowl victory party for the Detroit Lions. Explaining his decision to move from journalism to electoral politics, Pugh said, “I’m tired of just reporting what’s wrong.” As for his more immediate problems, he transformed them into an asset—an issue not of irresponsibility but of relatability, pointing out, “Just like many families, I’ve experienced personal tragedy. And just like many families, I’m facing financial challenges right now.”

Aside from his polished delivery, Pugh’s performance struck me as terrible. At one point, he told the moderator, straight-faced, “Well, the good thing is, personal finances have nothing to do with how the city is run.” He also had the annoying habit of referring to his finances as “my challenges,” as if he’d been nobly struggling to overcome some severe disability, like being been born with flipper arms and then deciding, through sheer force of will, to become a professional juggler.

Several of Pugh’s opponents provided even greater entertainment value. Kwame Kenyatta, a gaunt fifty-lhree-year-old sporting a pinstripe jacket, mustard yellow turtleneck, and brown kofia, had the best fashion sense of anyone on the stage, a sort of Casual Friday Afro-centric look. That April, Kenyatta and his wife had not only defaulted on the mortgage of their four-bedroom colonial home on Detroit’s northwest side but physically abandoned the property, simply walking away from the loan. When confronted with this fact by the moderator, Kenyatta was unapologetic. Flashing a tricky half smile and peering over his podium through permanently hooded eyes that gave him a serpentine quality, Kenyatta insisted he’d made a financial decision, “just like GM made a financial decision to go bankrupt.” This line received hardy applause, as did his bit of one-upsmanship of candidate James Bennett, an ex-cop who had declared himself “a blue-collar guy,” to which Kenyatta responded, “I’m street collar, not necessarily blue collar. I come from the streets.”

Mohammad Okdie, the only non–African American to make the final primary cutoff—Okdie’s parents were Lebanese immigrants—mentioned he regularly rode the bus. During his closing remarks, he declared, “I am you, Detroit.”

Gary Brown said, “I will not embarrass you.”

Kenyatta, delightfully, concluded with a quote: “As the Last Poets said, ‘It’s down to now.’”

Pugh asked the voters of Detroit for their support of his leadership, “flaws and all,” then flashed a grin.

On Election Day, the voters—such as they were: turnout was under 25 percent—wound up responding to Pugh’s message, and he became the new city council president. Brown, coming in second, became council president pro tem. After his victory, Pugh told the Free Press he’d be calling the newly reelected Detroit city clerk to congratulate her and also, more urgently, “ask[ing] her for a certified letter that I was the top vote-getter … and the salary that corresponds to the top vote-getter is $85,000 a year. That’s officially provable income. And the mortgage company was kind enough to postpone the sheriff’s sale.

“I’m on much more solid footing on negotiating,” he went on. “It’ll be wrapped up before the swearing-in. Hell, it may be wrapped up before December.”

* * *

As November approached, stencils began appearing on buildings around town featuring an anachronistic, bearded visage and the words RE-ELECT PINGREE. Elected in 1890, Hazen S. Pingree still reigns, pretty much uncontested, as Detroit’s finest mayor. Republican railroad barons thought they had hand-picked an acceptable leader from the capitalist ranks, one who gave (per Robert Conot) “every indication [he] would complaisantly respond to their desires.” Pingree, fifty years old, a Civil War veteran and owner of the largest shoe factory west of New England, surprised and infuriated his benefactors by becoming one of most progressive mayors in the country, siding with labor during a streetcar-workers’ strike and dramatically revealing the dirty dealings of the public school board (apparently, some things never change) during a surprise appearance at a Board of Education meeting, where he announced to his stunned audience, “You are a bunch of thieves, grafters and rascals! As your names are called, the police will take you into custody.”

Other echoes of futures to come: the depression of 1893 had left one-third of Detroiters unemployed. Along with securing money for an ambitious public works program, Pingree pioneered, nearly a century before it became a staple of the bright-new-ideas-for-saving-Detroit trend piece, an urban farming scheme in which more than three thousand families were encouraged (and partially subsidized) to grow vegetables on five-hundred acres’ worth of half-acre plots throughout the city. Because the program launched in mid-June, the only crops harvested that first year were turnips, beans, and late potatoes, and the gardens were mocked as “Pingree’s potato patches.” In the end, though, it became Pingree’s signature initiative, ultimately viewed as an ingenious pilot program by copycat mayors in Boston, Minneapolis, and New York.

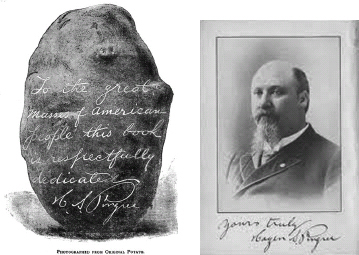

Pingree eventually became governor of Michigan, a vanguard presence of the coming Progressive Era, admired, and copied by towering figures in the movement like Robert LaFollette and Teddy Roosevelt. In his 1895 account of his battles with the status quo, Facts and opinion; or, Dangers that beset us, Pingree wrote that “monopolistic corporations” were to blame for “nearly all the thieving and boodling” besetting us and our cities and wonderfully described the white collar bandits of the late nineteenth century as “a grade of criminals of finished rascality.” The book’s frontispiece was a photograph of Pingree’s dedication of the volume to the “great masses of American people,” handwritten on a potato. (A note at the bottom of the page reads, “Photographed from Original Potato.”) It was as governor, campaigning against his would-be Democratic replacement in the mayor’s office, that he informed a crowd in Detroit that “this town needs somebody to tell the public-utility crowd to kiss something else besides babies.”

Frontispiece, Facts and opinion; or, Dangers that beset us

The yearning for a duly-elected savior like Pingree was understandable. In recent years, the only Detroit politician who’d come close to the old man’s panache—as terrible as it was to admit—was the Hon. Kwame Kilpatrick. From the moment I returned to the city, no matter what Bing or the council happened to be grappling with, a disproportionate amount of news coverage was devoted to the deposed mayor. It was like Nixon being sentenced to house arrest in the Lincoln Bedroom and still being allowed to call the periodic press conference. Kilpatrick had served time, moved his family to an expensive home in suburban Dallas, missed several restitution payments, and was ultimately sent back to jail. Still, his every move, voluntary or otherwise, caused seismic tremors in Detroit—a telling commentary on the power of his charismatic pull, even in exile and disgrace, and especially compared with those who had replaced him. Voters had declared their preference for the dull but steady Bing, Pugh the effervescent anchorman, Brown the crime-fighting Boy Scout—but still, they couldn’t tear their eyes from the larger-than-life figure born to command a room.

Part of the reason, of course, had to do with the soap operatic pull of scandal involving sex, all manner of corruption (shakedowns, nepotism, general kleptocratic rot), even murder. (Rumors had circulated about wild parties the mayor had thrown in the Manoogian Mansion, including one in which his wife arrived unexpectedly and allegedly assaulted an exotic dancer named Tamara “Strawberry” Greene. Later, the twenty-seven-year-old dancer was shot and killed at four-thirty in the morning while sitting in her car with her boyfriend on the city’s west side, feeding lurid but wholly unfounded conspiracy theories that had Greene snuffed by a mayoral hit man in order to prevent her from speaking publicly about the alleged party incident.) But there was an extra sting to Kilpatrick’s downfall precisely because, once upon a time, he truly had struck many as an energetic and even visionary leader who might alter Detroit’s trajectory through the sheer strength of his personality.

Kilpatrick came from a politically connected family—his mother, Carolyn Cheeks-Kilpatrick, was a U.S. Representative—and when Kwame was elected in 2001, at the age of thirty-one, he was the youngest mayor in Detroit’s history. I spent two days shadowing Kilpatrick in 2002,2 when he was celebrating his first year in office with a 75 percent approval rating, having already logged an impressive list of early-term accomplishments that included five thousand new housing starts and balancing the city budget, despite the inheritance of a seventy-five-million dollar deficit. At the time, the comedian Chris Rock gave an interview about preparing for his role as the first black president in the 2003 film Head of State; he didn’t cite Barack Obama, the obscure state senator from Illinois, as a model for his character, but Kwame Kilpatrick.

“Kwame got it—he was brilliant,” Kurt Metzger, Detroit’s most respected demographer, told me later, after everything had gone wrong. “He just understood data. Whenever I threw a number at him, he’d know it, and could respond with numbers of his own. And he’d be right!” Metzger smiled sadly. “Unfortunately, he was also a sociopath. But other than that … ”

Almost immediately, I took to the mayor. Despite his size, he moved with a relaxed, ambling gait. His head looked small atop such a bulky presence, his ears tinier still, with a slightly crushed quality, as if they’d been stuck to either temple as globs of half-baked dough. But Kilpatrick was a handsome man, with an easy, confident smile, and he backed his storied personal magnetism with obvious intelligence and a quick wit. He also possessed the natural charm advantage of the physically imposing, whereby little more than a reassuring nod or welcoming grin from a person twice your size triggers, on some dank evolutionary substrata, an involuntary rush of gratitude. When I heard rumblings about “immaturity” and “arrogance,” I was quick to write off the objections as generational, stylistic. Kilpatrick and I were close in age, and when journalists dubbed him “the hip-hop mayor,”3 I didn’t see it as an epithet, but, rather, a milestone.

Still, the cockiness of his administration—”swagger,” in hip-hop terms—was evident. One evening, when I joined Kilpatrick on an Angel’s Night patrol, the mayor’s press secretary, Jamaine Dickens, casually popped a CD into the stereo of his blue Crown Vic as we drove to meet the mayor. “Do you like Ludacris?” he asked. “This was our unofficial campaign song, just because we spent so much time on the road.” The rapper boomed, “You got to MOVE, bitch! Get out the WAY!”

Dickens smiled, flinched, and went on: “You know what? Our real song was ‘You Scared.’ You know that one?” To refresh my memory, he shout-rapped, in the manner of Lil’ Jon, the song’s auteur, its bullying chorus: “You SCARED! You SCARED! Bee-AAAAA bee-AAAAA!” “Bee-AAAAA” was short for “bitch.” (The actual title of the song was “Bia Bia,” with other choice lines including “Stop acting like a BITCH and get your HANDS up!”) Adding clarification, Dickens explained, “That was our song because it seemed like everybody was scared to endorse us.”

My exchange with Kilpatrick himself that night felt raw and honest, more so than the majority of interactions I’ve had with public figures. Earlier in the day, Kilpatrick had addressed a council of Baptist preachers (telling them, “The next wave of the Civil Rights movement is access to capital”); he’d since changed from a suit into brown Timberland boots, grey jeans, and an Angel’s Night sweatshirt the safety-orange shade of a deer hunter’s anorak. The night was proceeding smoothly and the mayor lapsed into a decided informality between stops. At one point, while a small group of us rode in the back of the black mayoral Suburban, Kilpatrick absently picked up one of the flashlights being passed out to volunteers and announced, “I wanna flash some people.” He began shining the light out the window. Then he illuminated his own face, like one of the ill-fated teenagers from the movie The Blair Witch Project, only instead of telling a campfire story, he began to imitate a man being hassled by a police officer.

“‘What you doin’, man?’

“‘Well, I’m blind, now. Could you take the flashlight out of my face? I ain’t going nowhere.’

“‘You being smart?’

“‘I’m always smart. I went to school, man. I’m just hoping you’ll take that flashlight down so we can have a conversation.’”

Shifting back to his own voice, Kilpatrick said, “They used to hate me.” He meant the cops. After falling silent for a moment, he turned to me and asked drolly, “Mark, have you had positive experiences with police officers?”

I said, “Positive? I don’t know. Probably not.”

The mayor said, “Heh.”

I said I guessed my experiences had been pretty neutral. Then I asked, “What about you?”

“I was getting hassled during the campaign,” Kilpatrick said. “The police department was against me. Vehemently against me. So that was going on. But I had a real bad experience with a police officer once. I thought he was going to kill me for no reason.”

I asked what happened. The mayor went quiet again, and seemed to be considering whether or not to tell the story. When he spoke, his tone had become more serious. “It was about three years ago,” he began slowly, “He told me I robbed something. This is Seven Mile here,” he said to the driver, before continuing: “I was standing in my driveway. I was trying to tell him that I lived there. A house down the street had been robbed. I was coming outside with my friend and we were about to go to the store and get some food. My wife was going to cook dinner. It was after church, so I was pretty well dressed.” The mayor cleared his throat. “The police pulled up and, to make a long story short, he put a nine-millimeter gun to my head, told me to get on the ground, or he was gonna shoot me.”

There was a long silence. Finally, I began, “So when he figured out you weren’t the guy—”

“No apology,” the mayor interrupted. He gazed out the window, shadows flickering across his broad face. “There were like four police cars by that point. Matter of fact, he was yelling, ‘I was following procedure, I didn’t do nothing wrong!’ He was such a bad officer. He’d been cussing at me the whole time. ‘I swear to God, you move, I’m gonna kill you.’ Another officer grabbed my friend and threw him in the car. I was this calm, talking to him just like this, but with a gun in my face. I said, ‘Just put the gun down. My license is in my pocket. This is my house.’ It was like three or four in the afternoon. Kids were riding their bikes, skipping up the street.” Kilpatrick chuckled mordantly. “It was a nice day.” Kilpatrick said the reason he didn’t get on the ground right away was because his two-year-old twins were standing in the doorway.

Later, of course, I wondered how much of the story had been bullshit.4

* * *

I visited Gary Brown one afternoon at his home in Sherwood Forest, a neighborhood of handsome brick estates with its own private security patrol. Brown’s political career had been the one thing Kilpatrick had inarguably bequeathed to the city, and the council president protem was certainly the most impressive of the new lot of Detroit politicians. We chatted in a sunny Florida room in the back of the house, where African masks hung on the wall above a Bose stereo system. Brown, dressed like a suburban dad, wore a zippered sweater and a pair of loafers with no socks.

Brown’s lawsuit had made him a well-liked public figure in Detroit,5 and once in office, Brown proved to be the most hard-headed of the new council, training the forensic obsessiveness he’d honed as a narcotics and internal affairs investigator on Detroit’s budgetary crime scene. Almost single-handedly, Brown pushed the council to propose far deeper annual spending cuts than the Bing administration—in 2011, $50 million more than Bing had proposed—not out of rightwing austerity-mindedness but because Brown understood the very real threat of a state takeover of Detroit.

By April 2012, when it became clear that Detroit, drowning in $12 billion of debt, would have to accede to some form of state control, Brown and Charles Pugh led the council in crafting a responsible compromise “consent agreement” in which a nine-member financial oversight board would oversee budgetary reforms. The consent agreement opened the door to more public-service union concessions and deeper governmental cuts, but also staved off the appointment of an emergency manager, which would have sidelined elected representatives like Bing and the council. Brown and Pugh came off especially well in comparison to Bing, who spent much of the budget crisis either engaging in dubious accounting tricks or seemingly angling to be appointed emergency manager himself, and to longer-serving council members like Kwame Kenyatta and JoAnn Watson, who played to their base with righteous-sounding but ultimately fatuous obstructionism.

At times, Gary Brown and Charles Pugh felt like two sides of the Kilpatrick persona, Brown embodying the wonk, Pugh the great communicator. If Pugh seemed weak discussing specifics of policy—the first time we met, he brought up his idea to bottle and market water from the Detroit River—he nonetheless assembled a smart, young team, and was generally upbeat and forward-looking rather than fixated on the racial and geographccal battles of the past. In a city like Detroit, where so many citizens had felt disenfranchished for so long, the ability to clearly and effectively speak to one’s constituents, as Pugh could, masterfully, struck me as no superficial tool.

To that end, Pugh spent an hour or two most Friday afternoons riding the city buses and mingling with the electorate. Using public transportation as a means of proving “relatability” has always been an easy PR stunt, but in Detroit, the very act of riding the harrowing, unreliable bus system became a deeply empathetic act of shared sacrifice. One Friday, when Pugh invited me to join him in the field, a woman at the bus stop glanced at us as she wandered by, then came to a full stop. “Hi, Pugh!” she called out. “What you doing out here?”

“Talking to people like you,” Pugh said enthusiastically.

When one of Pugh’s staffers informed him of the arrival of his bus, a look of concern spread over the woman’s face. “You gonna catch the bus, Pugh?”

“I ride the bus every week!” he called over his shoulder.

The woman snorted, seeming both skeptical and anxious for the young man.

On board, the driver recognizing the council president, evinced similar incredulity. Staring back at us in his wide rearview mirror, he shouted, “When was the last time you been on the Iron Pimp?”

Pugh said, “I ride the bus two or three times a month.”

“For real?”

Pugh said, “The very first time we rode the bus, it broke down on Woodward! Just so you know.” Then he added, “I love it because it keeps us connected.”

The driver said, “You about to get connected with some kids in a minute.”

Pugh’s staff laughed nervously.

We’d started at the central bus terminus, named for Rosa Parks, one of the few examples of ambitious and aesthetically pleasing new architecture to appear in downtown Detroit in the past several decades—most strikingly, the curved white awnings sheltering each bus stop, looking from the street like the billowing sails of a grand seafaring vessel, and appearing from directly below like the underside of a row of dirigibles, docked and awaiting take-off, either conjured image working as a fitting tribute to Parks, hinting as they did of the moment before an epic journey.

Over the course of our two-hour ride, I was the only white passenger, save for a single man with a ponytail and camouflage jacket who boarded for a brief stretch near Highland Park. On the bus, Pugh took a seat near the middle. It was not very crowded yet. One of the first passengers we picked up, a middle-aged man, took a seat in the handicapped area near the front, then spotted Pugh and shouted back a greeting. He told Pugh they’d met once at Eastern Market. Pugh asked if the man shopped there. “No, I work there,” the man said. When they’d met, he told Pugh, he’d been fixing a broken HiLo (a type of forklift), which seemed to puzzle Pugh.

“Hey, you got a pencil?” the man called out. “Write down this number. I want you to call my mama.”

Pugh wrote down the number and promised the man he would call his mother and tell her that he’d met her son on the bus.

As we meandered up Woodward, Pugh occasionally switched seats to chat with other passengers. His team members had spread out, too, distributing flyers with information about the council, including phone numbers and Internet addresses related to various city services and departments. The interactions highlighted, in a pitiless way, the difficulties many in the city faced. Pugh approached a pair of weary looking men and handed them flyers, asking brightly, “Y’all know anybody looking for a job?” The flyers contained information about city employment programs.

“Yeah,” one of the guys muttered, barely glancing at Pugh or the flyer. “Everybody.”

Another man in a knit Carhart cap took the seat behind Pugh and leaned forward. “I wonder if you can help me,” he asked. “I have a felony, fifteen years old, but they discriminate against me now when I’m trying to get work.” The man was gaunt, in his fifties, with a toothpick in his mouth and a nasty-looking bruise under his left eye. Pugh chatted with him for a few minutes, then asked if he ever used the Internet. The man said yes and Pugh handed him a flyer and told him to go to his website, where there was an entire section devoted to constituents with criminal records.

And so it went. One teenage boy turned out to be returning from a visit to his lawyer for a charge he didn’t want to discuss; he’d also been temporarily expelled from school. A group of high school girls discussed Raisin in the Sun with Pugh, who recommended various colleges and argued gently with the one who said she couldn’t wait to get out of Detroit. I noticed that one of the staffers, a stocky older man, stuck close to Pugh whenever he moved around, always sure to position himself in a seat nearby, no doubt acting as a sort of bodyguard. I wondered if they thought Pugh was in danger of being mugged while riding a bus in broad daylight.

During a lull, Pugh told me that he hoped to see more regional cooperation with the suburbs, that he would love for the planned light-rail line to connect Detroit with surrounding communities. Most of the constituent interfacing had gone well up to this point. But then an older man sitting behind Pugh perked up and noticed his famous neighbor. The man had an old-fashioned pair of oversized headphones hanging around his neck, and he reeked of booze. Leaning forward, he introduced himself to Pugh, then said, “I have a lot of questions for you. Why are you hiding back here?”

A glimmer of annoyance crept into Pugh’s voice, sounding odder because he couldn’t turn off its chirpier inflection. “I’m not hiding!” he said. “You just got on. You don’t know what I’ve been doing.”

The man nodded and said, “So, in regards to the change issue, I’m wondering, ‘What is our destination?’ For instance, this dumping right here.” The man nodded out the window to his left. On the other side of the street, there was a rubble-strewn lot.

“No, no!” Pugh said. “See, that’s not dumping. That was an abandoned building. It was taken down. That’s a good thing.”

The man considered this response, pursing his lips, then said, “So what you’re saying is, I’m not viewing urban blight. I’m viewing urban progress.”

Pugh didn’t seem to know if he was being messed with or not, but he stuck with his argument about abandoned buildings needing to be demolished.

“I’m part of your constituency,” the man interrupted. “And what you’re not hearing is, a couple of days ago, I saw trucks illegally dumping. These guys are making sixteen hundred dollars dumping in the city, and they’ve got no overhead. Man, in this area I’m talking about, you see mounds and mounds and mounds. It’s Trumbell and … and … Well, I’m an old man. I forget.”

“Elijah McCoy Drive?” Pugh asked. As the man spoke, Pugh had taken out his BlackBerry and pecked out a memo regarding the dumping location, or at least pretended to. “There are a lot of abandoned fields over there. It’s not far from where I grew up.”

“Do you remember Maryanne McCaffery?” the old man asked, referring to a beloved city council member from the Coleman Young era, now deceased. He asked Pugh about a specific bill McCaffery had championed. Pugh obviously had no idea what the man was talking about. “See, I read history,” the man said. “It’s important to know history.”

As he spoke, we pulled back into the Rosa Parks Terminal, and Pugh rose abruptly, his patience all used up. “When she was elected, I was seven years old, dog,” he noted sourly. “I wasn’t following politics then. Sorry.”

* * *

Dave Bing had initially pledged to serve only a single term as mayor. But by December 2009, in a year-end interview with the Free Press, the mayor reversed himself, declaring, “I never considered myself a one-term mayor. My nature is to finish what I start. Can I do that in this job? I don’t think so. It’s a ten-to-twenty-year process. I don’t know if I have that kind of time, but I’m not coming to this job saying I’m only going to do it for one term.”

The backpedaling was both unsurprising—he was a politician, after all—but also not, as Bing hardly struck anyone as enjoying his job or being particularly engaged with it. The Detroit News reported that Bing’s workdays rarely extended past 5:00 p.m. As a public speaker, he remained leaden and stultifying, unerringly tone-deaf to the expectations of his audience. Even his storied managerial skills didn’t appear to be so hot. He bragged in an early interview about not “believ[ing] in emails,” preferring to walk down the hall and look a person in the face, which, while presumably meant to convey old-timey virtue and simplicity, came off rather like a stubborn and bizarrely inefficient personal quirk. And in truth, becoming a wealthy auto-parts supplier in Detroit doesn’t necessarily prove any sort of genius-level business acumen, especially when you happen to be a local basketball star potential clients would be eager to meet.6

The Bing administration’s tepid rollout of the Detroit Works project in the fall of 2010 did nothing to boost the city’s confidence in its mayor. And over the following year, it became increasingly clear that Council President Pugh and Pro Tem Brown recognized Bing’s weaknesses. Brown was said to be exploring a senate run. Pugh, meanwhile, found it less and less necessary to mask his own obvious designs on the mayor’s office. The first time we’d met, shortly before Pugh’s own election, he had tiptoed around his ambition, shifting it over to anecdotal strawmen (“There are people who walk up and say, ‘You should have run for mayor.’ Not right now. Give me four years, as we downsize and get used to that, the innovations that we bring … ”), while undermining Bing via backhanded words of support (“He’s got a monumental task ahead of him, in downsizing government—and he’s the oldest man ever elected mayor in Detroit’s history.”). By the time of our bus ride, however, Pugh’s tone vis-à-vis Bing had shifted to open condescension: “All mayors have some growing pains, and obviously, Dave Bing is the quiet, unassuming type. I just don’t think he realizes the power he has. He’s too quiet. I know I would have done the right-sizing meetings a little different. There needs to be more door-knocking. People need hope. I wish Dave Bing would take the lead.”

All of this naturally decreased Bing’s incentive to assume a conciliatory tone with the council in general and the council president in particular. In the midst of difficult negotiations over the city budget, for example, Bing’s press office coolly announced that seventy-seven public parks would close for the summer because of the council’s fiscal outrageousness—a move that ultimately forced the council to blink and restore nearly $18 million of budget cuts they’d previously overridden a Bing veto to preserve. By most other metrics, though, Bing had few wins after three years in office: crime was up, the most elementary public services (the bus system, the lighting department) remained miserable failures, and a head-turning number of high-profile city hall departures left the impression of an administration in disarray.

While Detroit’s leadership had bickered, venture capitalist Rick Snyder had settled into the governor’s mansion in Lansing. Even more overtly than Bing, Snyder made much of his stiffness as a public speaker, proudly describing himself as a “nerd” in his campaign ads—he injected six million dollars of his own money into the campaign, outspending his Democratic opponent four to one—and trading on the public’s stereotypical association of nerdiness with a high I.Q. and a certain level of uptightness, which Snyder implied would act as twin virtues when it came to the governance of a state in desperate need of rebuilding.

Immediately after taking office, Snyder embraced supply-side economic solutions to address Michigan’s fiscal problems—basically, cutting taxes on most businesses while raising taxes on just about everyone else, in hopes of attracting new private-sector investment in the state. (Specifically, Snyder lowered corporate taxes by more than $1.5 billion a year, making up some of the difference by cutting state aid to colleges and universities by 15 percent, reducing K–12 education funding by $430 per pupil, and raising taxes on pensions.) More alarming still was the adoption of the Emergency Financial Manager law. As critics noted, the bill passed at a time when Michigan still had one of the country’s highest unemployment rates, which in turn was having a steep attritive effect on the state’s population (along with its tax base), the result being that dozens of local government leaders finding themselves staring down potential bankruptcy unless they enacted draconian cuts in basic city services and the unionized civic employees who provided them. At the same time, the federal government, and now the state government under Snyder, was actually reducing local aid.

Detroit was the fattest prize, for someone willing to take the most cynical, Machiavellian view of the Snyder administration, of Republicans foaming at the mouth to snatch the city back from the liberals—a racially coded word here—who’d run it into the ground. So, as Bing and Pugh spent a few weeks arguing over control of a city-run public access cable channel (really), others worried that such machinations were soon to become wholly irrelevant. In the end, the city-state consent agreement reached was infinitely preferable to emergency management: the mayor and council would retain their power, though their budgets would now be subject to final approval by the nine-person financial oversight board. Mayor and council would solely or jointly appoint five of the board’s members; the board would not have an emergency manager’s power to discard union contracts completely. Still, the city was basically agreeing to work with the state to slash payroll, sell off city assets, and outsource departments. Though Detroit’s elected leadership remained in place, it felt less relevant than ever; its powers, in the face of unworkable math, had basically come down to managed decline.

Gary Brown, ever the realist, was quick to declare the consent agreement a “great deal”—if, as he pointed out, “you look at the fact that we don’t have anything to bargain with, we don’t have anything to negotiate with, we’re down to the ninth hour, we don’t have any cash and we don’t have any leverage.”

1 A better-natured satirical collection of the (admittedly eminently) quotable Young, released in 1991, was printed in the style of Mao’s Little Red Book.

2 For a planned magazine profile, ultimately never published.

3 Partly, this referred to Kilpatrick’s youth and sartorial flair, but Kilpatrick had certainly lived up to his nickname, inviting Biz Markie to spin at his inauguration party and allowing himself to be sampled by the Detroit rap group Black Bottom Collective, on a ten-second track called “Best Not Keep Da Mayor Waitin’,” on which he exhorted the group to “‘come wit’ it Detroit style.”

4 Who could say? My friend Stephen Henderson, the editorial page editor at the Detroit Free Press, once witnessed a Kilpatrick performance in which the mayor, near tears, convincingly proclaimed his innocence to an assembled group of supposedly jaded Free Press editors and writers, Henderson among them, who basically walked away believing him.

As rumors of Kilpatrick’s after-hours partying at the mayoral mansion trickled out, I recalled how, at end of our night together, I’d overheard the mayor ask a member of his entourage, “So she’s gonna be able to come to the mansion tonight?” It was close to midnight. We’d seen the mayor’s wife at an earlier stop, but she had gone home with the children. (The mansion was being renovated, so the Kilpatricks were still living at their personal residence.) Someone noticed me standing there and quickly said, “cWe just found out a woman who does massages is going to be able to come to the mansion tonight. We go there to work sometimes, and she’ll come out if it’s been a long day.” I nodded, not sure how credulous they expected me to act. I decided to go with “extremely credulous.”

5 Well, not universally: during an interview, a prominent, politically connected local activist turned off my tape recorder and said, “Gary Brown is a punk bitch. What happens when you investigate your boss? You get fired. That’s what happened. He was serving at the mayor’s discretion. Okay, Kwame was a boner. He was a baller. You get to the position where a hundred and fifty women a year are throwing themselves at you, what do you do? You might hit one or two. If it’s okay with them and okay with your wife, why is it anyone else’s business?”

6 The shameless number of sports analogies used by Bing in speeches and interviews suggests he remains well aware of the power of his former athletic celebrity and has in fact been flexing those muscles for so long it’s now second nature. During my own half-hour interview with the mayor, he cited, as an analogy for his deliberative style of governance, how he’d always been someone who “makes layups and free throws, not three-pointers.”