CHAPTER EIGHT

FIRST WORLD WAR

Shimon Dov expected the world to end in a burst of divine radiance. There would be a knock on his door and he would open to utter clarity, absolute knowledge, perfect peace, and overwhelming joy: the Messiah had come at last! The scribe and his offspring in Volozhin and Rakov and New York and New Jersey, and all the Jews in Russia and Europe, in Vilna and Warsaw, Berlin and Moscow, London and Rome and Vienna, even the Jews in China and Africa and Australia and South America would rush to their synagogues to praise God and then stream as one people, one redeemed body, back to Jerusalem, where the Temple would stand again in all its holiness and might.

Shimon Dov did not expect his world to end with a bullet fired from an assassin’s rifle into the proud pampered body of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne. For Shimon Dov, for Europe’s Jews, the assassination of the archduke Franz Ferdinand, on June 28, 1914, ushered in the age of the anti-Messiah. It took three decades to complete the mission—and when it was done, the earth, at least one smoldering chunk of it, was emptied of justice, joy, clarity, light, and love. Shimon Dov at the age of seventy-nine saw it begin. He was blessed that he did not live to see it end.

—

When the news reached Volozhin that Germany, on August 1, had declared war on Russia, three old friends—Fayve the tailor, Oyzer the postman, Naftoli the bookbinder—were gathered as usual in the Klayzl synagogue on Vilna Street. The talk, of course, turned to the future. Their country was now at war with the most powerful, most modern, most heavily armed nation in Europe. What would happen to them, to their families, to their beloved shtetl? Nothing to worry about, Oyzer the postman told his friends resolutely. Russia was not only immense but immensely strong. So strong that she could choose to fight where she wanted. Siberia, the Caucasus, the fertile plains of Ukraine, the deserts of Manchuria: the tsar controlled all of this territory and he would fight where his commanders advised him to fight. Volozhin was safe—they could all relax. With a huge empire under his belt why would the emperor pick their little town for a battlefield?

While Oyzer held forth, Nahumke, a graduate of the yeshiva, was sitting nearby, ostensibly immersed in a book. But the yeshiva man looked up when there was a pause and launched into a story—a true story he insisted: There once was a poor Jew in Volozhin with six ugly daughters, one nastier than the next, all of them impossible to marry off. One day the shadken—the matchmaker—appeared at the house of the poor Jewish father to announce that he had found a most impressive match: the only son and heir of Count Tyshkevitch, the nobleman who owned forty thousand acres of estates and forests surrounding Volozhin. There was just one problem: the prospective groom was a goy. The poor Jew was outraged, but his wife was intrigued—and so, after much soul-searching and beard-tugging, he summoned the shadken back and gave his consent. “Wonderful,” replied the shadken. “Now we have to go see if the count and his son are agreeable.”

“The moral of the story,” Nahumke told his friends, “is that even though Russia may claim she will fight where she chooses to fight, first she needs to get the consent of Germany and Austria. Are you sure that they would agree to do battle in those precise places and not here in Volozhin?”

Nahumke was prophetic. A little more than a year later, the German army was virtually on their doorstep.

—

Shimon Dov was convinced they had been spared. When Russia mobilized, half a million Jews were called up to fight in the tsar’s army, but his sons and grandsons were not among them. Avram Akiva and his three boys were safe in America. The same with Yasef Bear, Leah Golda (who had emigrated with her family in 1911), Herman, and all of their sons. Arie was dead, and Arie’s two sons, Yishayahu and Chaim, were too young to be drafted. The only ones left within range of the imperial recruiting officers were Shalom Tvi and his family in Rakov. But, praise God, Shalom Tvi had only daughters—four of them once Feigele, the youngest, was born in 1912, two years after Sonia. Shalom Tvi himself was forty-two the summer war was declared—too old for the army. The news was dire—immense battles were being fought in the Pale, shtetlach were on fire, Jews were being evacuated, robbed, killed, denounced as traitors—but at least the family was safe.

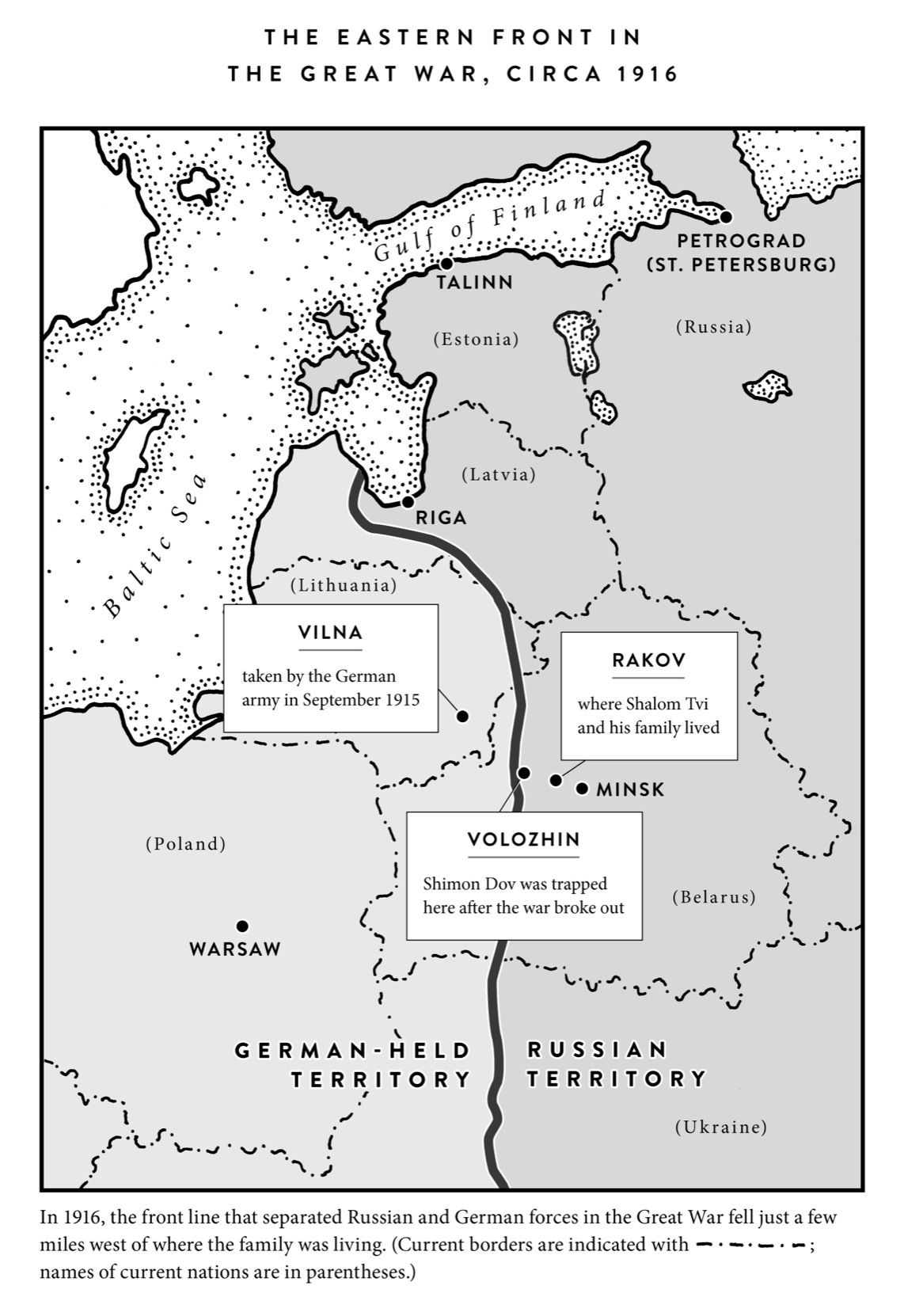

Shimon Dov clung to this belief for as long as he could before the reality of the Great War closed in. In the initial chaotic months, the opposing armies had made a series of rapid advances and retreats in the borderlands of Eastern Europe, “swaying back and forth in Poland and in Galicia,” as one Yiddish daily reported, and fighting “every inch of ground in Jewish towns and villages.” But in the spring of 1915, the swaying stopped and the movement turned decisively in one direction: east. The Germans mounted a push into Russian territory and the tsar’s army was powerless to halt it. The heavily fortified Lithuanian city of Kaunas fell in the middle of August; Smargon, where Harry and Hyman had done their apprenticeship, was overrun at the start of September; and Vilna, the regional capital, with its large cultured Jewish population, was in German hands by the middle of September. At the end of September the Eastern Front congealed along a line that sliced south through the Pale from the Baltic to the Red Sea.

The line fell so close to Volozhin that on maps the name was bisected. The yeshiva town was now a besieged outpost on the Eastern Front—still inside Russia but close enough to the line of battle that Shimon Dov was within range of artillery and in earshot of machine-gun fire. At night the eighty-year-old patriarch awoke to the repeating earthquake of exploding shells. Week after week, he watched two endless currents flow in opposite directions along the town’s main street: Russian soldiers and Cossacks moving west with their supply wagons and unwieldy artillery pieces mounted on limbers, while refugees from evacuated towns and villages streamed east. The Volozhin marketplace filled with the homeless, the wretched, the hungry and dispossessed. Yeshiva boys were routinely dragged from the school by Russian military police, marched off in shackles to Minsk, and thrown into the Russian army—or prison. The tsar’s government, deeming all Jews potential traitors, ordered mass deportations from shtetlach at the front. Some 600,000 Jews were sent packing into the Russian interior, and as many as 200,000 Jewish civilians were killed behind the Russian line. Peasants from the surrounding farm villages were also being evacuated en masse. With winter looming, those remaining in Volozhin wondered where they were going to get food.

The neighbors warned Shimon Dov that it was now a capital offense to speak Yiddish in public. The Russians had noticed that Germans could understand Yiddish—which is essentially a German dialect—and they accused Jews at the front of passing secrets to the enemy. Yiddish speakers were suspected of spying, and spies were shot on sight.

Behind their hands, the neighbors whispered that the shtetlach that had fallen to the Germans were the lucky ones. Russian soldiers raped, plundered, and torched Jewish homes, just as they always had. Cossacks were desecrating synagogues, smashing headstones, digging up Jewish graves because they believed that Jews buried their dead with their money. But the Germans were different. German soldiers were civilized, law-abiding. When they wanted something, they paid for it. Or so they thought in Volozhin.

Rakov, twenty-five miles east of Volozhin, was a day’s march from the front—far enough that Shalom Tvi did not have to worry about forced evacuation, but close enough to absorb the shock waves. It turned out that Shalom Tvi was wrong when he assumed he was too old to be drafted. After the losses of 1915, the desperately depleted Russian army was pressing every able-bodied man under fifty into service. Rakov was picked clean, but somehow Shalom Tvi escaped. Maybe his leather business was considered critical to the war effort (saddles, straps, coats, gloves); maybe he secured an exemption because he had four small children to feed; maybe his angel interceded on his behalf. Whatever the reason, Shalom Tvi managed to remain at home during the war to look after his family and their business.

Rakov families that could afford it sent their wives and daughters to Minsk “lest they fall prey, Heaven forbid, to the lust of the soldiers and Cossacks,” as one resident wrote. Shalom Tvi and Beyle had no relatives in Minsk and lacked the means to pay for lodging, so it’s likely that the mother and daughters stayed put. Day by day, they watched the town swell with refugees. “Old and young, men and women, were carried by the huge wave, heading to the interior of Russia. And they all passed through Rakov,” wrote one of their neighbors. “They would congregate in the market square, blocking the roads with their wagons, boxes, sacks, furniture, and bundles. Bundles upon bundles, of all kinds, holding the poverty which was somehow saved from the jaws of destruction. Sighing and choked weeping filled the air. They would sit, like mourners, on the ground, hungry and thirsty.” Shalom Tvi listened in horror as the refugees told how Jews in the opposing armies were forced to fight against their fellow Jews—brother against brother. Again and again, a story was repeated of a Jewish soldier who was about to make the fatal plunge with his bayonet when he heard the enemy cry out in Hebrew, “Shema Yisrael!”—“Hear O Israel”—the first words of the most essential Jewish prayer. Had Shalom Tvi been drafted, this might have been his fate.

No record has come down of how Shalom Tvi and Beyle survived the first years of war. That the business suffered is certain. “The World War brought complete ruin and destruction to the industry of Rakov,” wrote a shtetl historian. “Because of the economic difficulties and the drafting of the farm workers, the farmers and estate owners stopped buying the agricultural machinery which was produced in Rakov. Many of the factory owners (or as they were called: ‘Mechanikers’) were drafted into the army; others left Rakov and were spread all over the globe. As a result, factories were shut down, and the end came to the industry of which Rakov was famous for generations.” By January 1916, with the front line more or less fixed, the flow of refugees ceased and Rakov surrendered to its winter torpor. Occasionally a convoy of ambulances careered through town bearing wounded or frostbitten soldiers; then the frozen silence closed in again.

Word came that Volozhin, which had been sealed off by the Russian army due to its proximity to the front, was on the verge of starvation. The yeshiva was emptying as bochurim were drafted or imprisoned. Those who remained struggled to keep the light of Torah shining, but they were slowly dying of hunger because the townspeople had no food to spare. In a neighboring shtetl, Cossacks lounging in the synagogue ripped up the Torah scroll and used pages of the Talmud to roll cigarettes: Volozhin’s holy books would be next. A letter appealing for emergency aid was smuggled out of the yeshiva and delivered to Rakov’s community leaders. After much soul-searching, Rakov residents finally decided to hold back a portion of the food they had been distributing to refugees and send it to the Volozhin yeshiva instead. A sleigh was loaded and Rabbi Kalmanovitch set out. The bochurim received him like Bar Kochba, and the women of Volozhin got busy making bread and noodle kugel. And so the revered yeshiva, having risen from the ashes of nineteenth-century fires and the enforced closure by Russian authorities, survived for another season.

Two years into the war, Shalom Tvi and Beyle’s youngest daughter, Feigele, fell ill with scarlet fever. It tore the parents’ hearts to see their four-year-old so weak and undernourished, but how could they feed the child properly with soldiers and stragglers plundering the garden, and with milk, eggs, and meat so hard to come by? Everyone suffered in the towns near the front, but the young and old suffered most. The doctor was summoned and medicine was prescribed—no one remembers what it was, though it must have been very strong. Feigele was put to bed in a room by herself so as not to infect her sisters. Miserable and frightened, the child drifted in and out of burning sleep. Her mother had told her that the medicine would make her better—so why not take more and get better faster? The medicine was on the table beside the bed. When no one was looking, Feigele opened the bottle and drank it all down at once. Her parents found the empty bottle and the tiny cold corpse. “It’s impossible to describe my mother’s feeling,” Sonia, six years old at the time, told her own children many decades later. In the family photos taken after Feigele’s death, Beyle looks stricken. She never stopped blaming herself. She never recovered. Next to the 600,000 refugees, the millions who had already died of bullets and shells, and the millions more who would die in the battles and influenza epidemic to come, a tragedy in a darkened bedroom is a speck of dust. But for the parents who lost their daughter, this is the history that matters.

Shalom Tvi and Beyle were both devout, strict in their observance of the commandants. But they wondered how God could let them go about their lives—unwitting, heedless—while their beloved child poisoned herself to death.

In March of 1916, the Russians tried to punch their way back toward Vilna with a massive offensive—more than 350,000 men, 282 big guns, a huge stockpile of artillery shells and poison gas, cavalry, infantry, machine guns, bayonets—the combined arsenals of traditional and modern industrial warfare. All to little or no avail. “Epic confusion” snarled the Russian push. In the end, the Germans held on to Vilna; the Russian army suffered losses of 100,000 men, and 12,000 more succumbed to frostbite. The Eastern Front remained where it had been.

The winter of 1916–1917 was a bitter one. The cold and snow were so intense that roads and rail lines became impassable and food deliveries were disrupted to Russian cities; what food got through was fantastically expensive due to rampant inflation. In Rakov, there were so few vigorous men left that the Russian authorities began pressing the elderly into forced labor. “They were put to work digging trenches, cutting down trees, and other forms of hard labor, in exchange for dry bread and water,” recorded one resident. “One cannot describe the great suffering of the town people during that period.” In Volozhin, still on the front line, all trade had come to a halt; a stamped permit was required to enter or leave.

Shalom Tvi managed to secure a permit for his father. A congenital worrier, Shalom Tvi had been going out of his mind at the idea that his eighty-one-year-old father was living all by himself in a starving town at the front. He greased a palm, got the necessary papers stamped, and brought Shimon Dov to live with him and his family in Rakov. The scribe had precious few possessions. He took up hardly any room in his son’s house. Pious, charitable Beyle did everything she could to make her father-in-law comfortable.

The long years of war had eroded the patriarch’s will to continue. Who would want to live in a world where Cossacks shredded the sacred Torah and rolled tobacco in the pages of the Talmud? On February 4, 1917 (12 Sh’vat, 5677), with temperatures plunging across Russia and food shortages worsening, Shimon Dov HaKohen died. His body was laid to rest in the Rakov Jewish cemetery, the cemetery of exile. The deceased grandchildren—Shalom Tvi’s daughters Shula and Feigele and the two babies lost to Avram Akiva and Gishe Sore—may have been buried nearby, but the stones of the children have disappeared and only Shimon Dov’s headstone remains at the back of the cemetery near the fence. “He was strong in Torah, he will rest with the hands of the Kohanim,” reads the Hebrew inspiration—and a pair of hands, the thumbs almost touching, the fingers spread in priestly blessing, hovers over the text. It was a comfort to Shalom Tvi that his father’s grave was at the cemetery’s far edge. Descendants of Aaron are forbidden to enter a cemetery—but Shalom Tvi could walk to the side and gaze through the railing at the patriarch’s grave while he recited the mourner’s kaddish. As long as Shalom Tvi remained in Rakov, his father’s soul would be attended to.

Abraham and Sarah were already in mourning when word reached Abraham that his father had died in Rakov. A few months earlier, their daughter Anna, a delicate black-haired girl of twenty-two, had been diagnosed with tuberculosis. On the advice of a doctor, Anna was packed off to a sanatorium in New York’s Catskill Mountains, but it was too late to do her any good. Anna died on November 1, 1916, and Harry was dispatched to bring the body home. Sarah had now lost three of her nine children—two buried back in Rakov, and now Anna, dying alone in a sanatorium at an age when most young women were just starting their lives.

With the death of Shimon Dov, the mantle of the patriarch passed to Abraham, the firstborn son. And finally Abraham was in a situation worthy of a patriarch. After eight years in America, the golden door had creaked open for him a bit. The business was now bringing in enough money that the family was able to leave the Madison Street tenement and move into a clean modern apartment building in the Brooklyn neighborhood of Williamsburg, a short stroll from the East River. No more cold-water flat on the dingy courtyard. The Roebling Street apartment had steam heat and unlimited hot water.

The war in Europe was bringing prosperity to neutral America, and the Cohens and their business rose with the tide. Now when Abraham wrote to his brother in Rakov, he sent a little money along. And judging by Shalom Tvi’s letters, the family in Rakov was going to need all the help they could get. Russia was once again in turmoil, and who knew where it would lead or when it would end.

On March 8, 1917, a month after the death of Shimon Dov, Petrograd, as Russia’s capital was now called, erupted in protest. It was International Women’s Day, and thousands of disgruntled women—textile workers, students, peasants, even a scattering of society ladies—marched in the street to decry the lack of bread. Police and Cossacks were called in, but they were powerless to suppress or disperse the crowd. For some reason, no one had thought to issue whips to the Cossacks that day—an oversight with serious consequences. The uprising was reminiscent of 1905—with this signal difference: after three years of war and a winter of food and fuel shortages and unbearable breadlines, not only the people of Russia but also the army had reached the breaking point. The strike of March 8 (February 23 in the old-style Julian calendar that was still in use in Russia) turned out to be the gust that brought down an empire: it was the start of the Russian Revolution. The following day the strike doubled in size, and two days after that, soldiers called in to quell the uprising turned on their officers in open mutiny. The Petrograd chief of police, rounding on the protesters with a bullwhip, was surrounded, forced from his horse, disarmed, beaten with a piece of wood, and then shot through the heart with his own revolver. One week after the women of Petrograd took to the streets shouting “Bread!” the tsar was persuaded to abdicate. On March 21, the imperial family was placed under arrest.

Romanov rule was over. Yet it was far from clear what would take its place. In the power vacuum that followed the autocracy’s collapse, an unwieldy power-sharing arrangement emerged in which a provisional government, representing the elites (progressive politicians, liberal landowners, bourgeois professionals and intellectuals), ruled side by side with the Petrograd Soviet, a grassroots council of workers, soldiers, and radical politicians that was modeled on the soviets (councils) that had sprung up during the 1905 revolution. The assumption, or hope, was that the dual power arrangement would in time evolve into a single democratically elected government, but that was not what happened. As of March 15, 1917, Russia had no head of state—but it was still committed to fighting a devastating war. Had the world been at peace, revolution might have ushered in a stable, possibly democratic future. But revolution in the midst of world war proved to be catastrophic.

The Jews of Rakov and Volozhin and a hundred other shtetlach at the front erupted in wild euphoria at the news that the tsar had fallen. But joy, as always in Russia, was tempered by anxiety. Revolution had exploded and fizzled before; upheaval yielded freedom first, then repression and pogroms. Meanwhile, the war continued, practically at their doorstep. Though more and more soldiers were melting away and returning to their villages, though the officer corps was in shambles, though radicalized workers and soldiers were demanding with rising stridency that Russia pull out, still the fighting on the Eastern Front went on with no end in sight. Rakov and Volozhin Jews were giddy with their new rights, but their sons, those sons who remained after two and a half years of slaughter, were still being marched off to fight and die.

Of the three Cohen brothers, Hyman was the most taken with Germany. He loved the precision of German workmanship on clocks and watches, and his first job in New York, before A. Cohen & Sons got started, had been for the German-based Kienzle Clock Company. When Kienzle’s president came over to inspect the New York operation, he was so impressed with Hyman that he offered to bring him back to Germany and train him in the manufacture of clocks. Hyman would have jumped at the offer had his mother not refused to let him go.

When Europe went to war in the summer of 1914, Hyman was naturally sympathetic to the German side. He was not alone. Even if they didn’t share Hyman’s love for German craftsmanship, the majority of American Jews supported Germany because it was fighting against Russia, the land of the pogrom. Russia’s enemy was their friend—it was as simple as that. The pro-German stance was reinforced by stories and letters that came from the Pale attesting to how much better Jews fared in territory conquered by Germany. Under the Germans, there was no rape, no plunder, no desecration of synagogues. German officers billeted in Jewish homes were considerate, even kind. Germans laid down the law, but it was the same law for Jews and gentiles. So even though England and France were more appealing politically and socially than the Central Powers (Germany, Austria, and the Ottoman Empire), Jewish America had very little appetite for the Allied cause. Jewish socialists abhorred the war as a capitalist plot to distract workers from their legitimate struggle. Jewish moderates worried about the consequences of an Allied victory for their relatives still in Russia. Apolitical Jews shrugged their shoulders and thanked God that they had gotten out. But the consensus was that a Jew would have to be crazy to fight on the same side as the tsar.

Everything changed when revolution broke out in Petrograd. With the tsar gone, with Russian Jews granted full civil rights, suddenly the world was a different place—not only on Nevsky Prospect but on East Broadway. Even William and Itel’s beloved Forward abandoned its socialist-pacifist stance to declare, “There is nothing more to discuss. Feelings dictate, reason dictates, that a victory for present-day Germany would be a threat to the Russian Revolution and dangerous for democracy in Europe.” The revolution for which Itel and William had been chased out of Russia twelve years earlier had resurged and triumphed at last. At a stroke, American Jewry renounced Germany and realigned itself with the Allies. On March 20, five days after the tsar abdicated, twenty thousand American Jews packed New York’s Madison Square Garden, shouting and dancing in the aisles to celebrate the revolution.

They were dancing on an earthquake. That same day, President Woodrow Wilson assembled his cabinet secretaries in Washington, DC, and sought their advice on the situation with Germany. Wilson had been reelected the previous November on the promise to keep America out of the war, but in the late winter of 1917 that promise seemed doomed to be broken. On February 1, the Germans announced their intention to resume unrestricted submarine attacks on Atlantic commercial shipping, and several American vessels were sunk by German torpedoes in the following weeks. In March, as revolution swept Petrograd, the American press intercepted and published the so-called Zimmermann telegram, in which Germany’s foreign secretary, Arthur Zimmermann, was instructed to secretly enlist Mexico as Germany’s partner in a war against the United States. Zimmermann was told to dangle the promise to “re-conquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona” as an incentive for Mexico to join with Germany. Public pressure on the Wilson administration to deal with German aggression had been mounting all winter, and the Zimmermann telegram was, in the minds of many, the tipping point. Wilson felt he no longer had any choice. He presented the options to his cabinet, and on March 20 they voted unanimously to go to war. Two weeks later, Wilson made his case before Congress. “The world must be made safe for democracy,” the president exhorted America’s lawmakers—and the lawmakers agreed. The Senate reached its decision on the night of April 4—82 voted for war, 6 against. In the predawn hours of April 6, the House vote was tallied: 373 members of Congress in favor, 50 opposed.

Had the family stayed in Rakov, Abraham’s three sons would have been drafted into the Russian army and sent to the front. But now, just when revolution had freed Russia’s Jews, the war had crossed the ocean and crashed into their home in Brooklyn. None of the boys was safe from conscription after all.

June 5, 1917—National Draft Registration Day—dawned fair and mild over New York City with a soft breeze out of the south. The temperature had approached eighty the previous day—and what green there was in the city looked bright and fresh and miraculously clean. Nowhere more miraculous than in the tiny garden of the narrow three-story Williamsburg row house at 73 South Tenth Street, where the Cohen family had just moved from Roebling Street. At last, Abraham and Sarah had a home of their own—not a couple of rooms off a shared hallway but a whole house rising out of God’s earth with a bit of grass in front and a small bed in back where Sarah could grow a few flowers and vegetables and remember her garden in Rakov. Harry and Hyman were careful when they left the house that morning not to crush a single precious leaf or blade underfoot. Freshly shaved, neatly dressed, and nervous as hell, the brothers walked together to the local polling place to register for the draft. Every male between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-one was doing the exact same thing—not only in New York City but from coast to coast all over the country. Citizen, immigrant, naturalized, disabled, disaffected—it made no difference: all had to register for the draft that Congress had been forced to reinstate in order to bulk up America’s paltry army of 210,000 men (seventeenth in the world). Harry was twenty-eight, Hyman was twenty-four—right in the bull’s eye of Uncle Sam’s ten-year draft target—and so, they went off to do their civic duty along with 10 million other American males.

Sam, who was twenty-seven, wasn’t with them because Sam was now a married man with a place of his own. Four years earlier, he had married a girl named Celia Zimmerman, a fellow Russian Jew, and the couple was now keeping house on John Street—not in Williamsburg, like the rest of the family, but in Brooklyn’s Vinegar Hill neighborhood near the Manhattan Bridge. The two houses, though just a couple of miles apart, were in different precincts, so Sam had to go off by himself to register that morning. But before he could get out the door, Sam had to deal with his wife. Celia was flighty and high-strung and two months pregnant, and this war was making her frantic. What if they took him? What if he never came back? What if he came back with his legs blown off? In truth Sam was worrying himself.

It was the cusp of summer, but in Brooklyn and Manhattan it felt like the Fourth of July. At the stroke of seven when the registration stations opened, the whole city filled with the joyous noise of church bells tolling, horns blasting in the harbor, factory whistles shrilling. The avenues were bedecked with flags and bunting, and in the parks, bands and choruses belted out patriotic songs and marches. You couldn’t walk ten blocks without hearing the National Anthem. Eight hundred interpreters stood by to assist foreign-born registrants at the 2,123 stations that had been set up not only at polling places but also in storefronts, schools, barbershops, even funeral parlors. “I do not anticipate any trouble,” said Mayor John Purroy Mitchel (the so-called Boy Mayor of New York, who would die the following year at the age of thirty-eight while training with the fledgling air force). “But if there is any trouble, the police will be ready.” Indeed, in Williamsburg, the city had deployed one hundred extra policemen to break up protests threatened by socialists; a machine-gun squad, thirty-five motorcycle police, and two hundred cops armed with rifles were on hand—just in case.

The city was “prepared for anything short of invasion” reported the New York World—but the registration of some 610,000 New Yorkers unfolded peacefully. There was certainly no trouble from the Cohen brothers. Harry and Hyman filled out their cards under the watchful eye of registrar Edward P. Kearney, while Sam submitted his card to one D. H. Leary at Precinct 152. Though all three were citizens now, none of them showed much appetite to serve in the armed forces of their adoptive country. On line 12 of the registration card, in the space beside the question “Do you claim exemption from draft (specify grounds)?” Harry wrote “Yes break up the business and support of father and mother.” Sam wrote “Weak lungs.” And Hyman wrote “Yes. Support of mother.”

Six weeks later, there was a lottery drawing in Washington, DC, to determine the order in which registrants would be called up, and as luck would have it, all three of the brothers received very low numbers. Hyman, convinced that his civilian days were numbered, managed to get himself invited to the Catskills summer resort where his sweetheart, Anna Raskin, was vacationing with her family. Might as well make time while there was still a chance. Hyman could be gruff and scrappy, but he pitched as much sweet woo to lovely Anna as the senior Raskins would tolerate. By the time he returned to Brooklyn late in the summer, the couple had evidently reached an agreement. Sam and Harry, meanwhile, toiled away at A. Cohen & Sons and anxiously checked their mail.

The U.S. War Department intended to have 687,000 new recruits in uniform by autumn, and the first round of call-up notices went out at the end of August. Sam was one of the lucky recipients—but the army didn’t want him. At his physical, the examiners concluded he was too nearsighted to pick off German soldiers. In any case, he was short and stout and married and claimed to have weak lungs, so all in all not very promising soldier material. Harry was also refused. So that left Hyman. He got the call a few weeks after returning from what he called his “long date” in the Catskills. The War Department ordered him to report to his Brooklyn draft board for processing and warned that he was now “in the military service of the United States and subject to military law. Willful failure to present yourself at the precise hour specified constitutes desertion and is a capital offense in time of war.” Hyman showed up at the appointed hour and got in line for his physical with hundreds of other tense young Brooklynites. Medium in height and build, good-looking in a kind of hooded way though none too muscular after years shuffling papers and schlepping flatware samples, Hyman was a perfectly adequate specimen of Jewish American manhood. Neither flat-footed, alcoholic, myopic, or sexually degenerate, Hyman passed his physical with flying colors. The examiners told him to get dressed, go back to work, and await the next communiqué from Uncle Sam. It wouldn’t be long.

All that summer and autumn, as the United States shambled into war, violence and uncertainty convulsed Russia. The Germans had facilitated Vladimir Lenin’s return to Petrograd, in April, on the assumption that the Bolshevik leader would further destabilize Russia, and they were right. Fierce, grim, and disciplined, Lenin pushed for the extreme solution. He demanded that the bourgeois provisional government be overthrown at once and replaced by a government of those at the bottom of Russian society—urban workers, disaffected soldiers, and the disenfranchised rural poor. Russia must withdraw immediately from the world war; rural estates must be broken up and redistributed; food must be made affordable for the starving masses. Large angry crowds took Lenin’s call for “all power to the Soviets” to the streets. The message hit a nerve—even Lenin was surprised by how rapidly the ranks of his supporters swelled that summer. In June, Alexander Kerensky, a moderate socialist who was then minister of war and would shortly take over as head of the provisional government, launched a disastrous military offensive that only played into the Bolsheviks’ hands. Morale collapsed in the army; desertions increased exponentially. In the first week of July, the streets of the capital filled with half a million armed deserters and militant, radicalized workers. In September, the Moscow Soviet went over to the Bolsheviks, and on October 23, the Bolshevik Central Committee called for the armed overthrow of Kerensky’s provisional government.

The triumph of the so-called October Revolution was swift and all but bloodless, at least in the capital. Led by Trotsky, the Bolsheviks stormed the Winter Palace on the night of November 8 and took control of the government. “We shall now proceed to construct the socialist order!” Lenin proclaimed in his harsh monotone to a rapturous crowd.

In Rakov, hundreds of jubilant young Jews marched to the marketplace to the strains of the “Marseillaise” blared out by the band of the revolutionary Russian army. “How bestirred were our hearts!” wrote a nephew of Sarah’s named Zelig Kost, who was among the marchers. “The whole town rose with us, the marchers, like waves in a stormy sea. We had great hopes. We sang about a new emerging world, a superior world where the tortured Jewish people would find their rightful place. Ah! How quickly the illusion vanished.”

A scant seven months had passed between Lenin’s return and the raising of the red flag over the Winter Palace. A “decree on peace” was the new leader’s first proposal to the Congress of Soviets. It was approved unanimously.

Peace was what the people most fervently hoped for. But as Zelig Kost and his young comrades in Rakov discovered, peace was the first illusion to vanish after the revolution.

Hyman turned twenty-five on November 5, a Monday, three days before the Bolsheviks seized the Winter Palace. A full day of work lay ahead of him at A. Cohen & Sons. Though Hyman and Harry were no longer roommates—Harry, at the age of twenty-eight, had finally left home and moved into a place of his own on West 150th Street in Manhattan—they were still brothers and partners, and they still spent every day but the Sabbath working together side by side. Nonetheless, Hyman felt compelled to sit down that morning and write Harry a long, emotional letter. His orders from the War Department were due to arrive any day, and the birthday letter had the urgent self-dramatization of a young man face-to-face with his own, possibly heroic, death.

“You know me to be a poor writer,” Hyman began, but he needed to explain his “present feelings in my own poor way.” He had recently heard at a lecture that “when a boy enters his twenty-fifth year he at the same time enters into manhood, and a man should therefore take inventory of himself, look over and examine carefully what he has done in the past, and make new plans for the future.” And so:

I have taken inventory of my self to-day and I can tell you that with the exception of a few minor things not even worth mentioning I was pleased with my past work and I started to make plans for the future, but I couldn’t go very far, and didn’t make many plans, as at the start of my planning I remembered my self that this birthday came in a month in which I may have to give up all my plans for a while, as our government will very soon start to do all the planning for me.

Hyman waxed nostalgic over the five and a half “very pleasant” years he and Harry had spent as business partners:

We struggled together when everything about looked complete failure, and we were, and are, both sharing the honor now that we have brought for our business a little success and its good name in the “business world.”

I am approaching very rapidly the day when I’ll have to stop for a while to take active interest in the business, and while I appreciate the hard work Sam has done for us, we know that he only can do hard inside work (labor) and he couldn’t run the business even for a week. I therefore want you although you will have to work much harder, [to] do some of my work, follow my principals [sic], and also protect, and take care of my interest as well as of your own, during my stay in the “National Liberty Army.”

To Harry Cohen my friend I have this to say, we have been friends for a very long time, our friendship started in 1906 in the little city, or town of Smargon, Russia, when we worked to-gether in the little old Watchmaker’s shop owned by Mr. Rudnick. You undoubtedly remember how you worked for 2.50 Rubbels [sic] a week, and with your small salary we lived to-gether in a little room 10 X 6. . . . When in 1909 I came to this country to-gether with our parents and our sister Lillie and our late sister Anna, our friendship was resumed, and in fact we were more united, and if on one or the most two occasions we had a misunderstanding it only kept up for a few hours, our friendship couldn’t stand much longer.

Moved by his own eloquence, Hyman signed off emotionally:

We have seen brothers drifting apart from one another, but we have always stuck together, we were real brothers, and as my brother I don’t ask any more but I demand of you in other words I draft you to take good care of our parents, protect them, support them, and keep up their spirits. . . . Take care of my interest, and when I’ll return, and I hope in the very near future, we will start life again as the best Partners, Friends, and Brothers one for all, and all for one. Unity the key of success. Yours for an early and general world Peace your Partner your loving brother your Friend Hyman.

Hyman’s induction orders arrived in the mail two weeks later and he reported as instructed to Camp Upton out in the scrub flats of central Long Island. The 77th Division—the so-called Melting Pot or Times Square Division, assembled from raw immigrant recruits from the ghettos of the Lower East Side, Brooklyn, and the Bronx—was training at Camp Upton when Hyman got there. The division’s commanding officer despaired when he learned that the men he was in charge of spoke forty-three different languages—“the worst possible material from which to make soldier-stuff.”

Hyman soon found out that anti-Semitism was rampant in the army. He wised up fast: if a guy called you a kike, there was no use whining to your sergeant—you had to deal with it with your fists. Anyway, it wasn’t just Jews. Hunkies, Pollocks, Guineas, Chinks all got razzed, picked on, shoved out of the chow line, denigrated as hyphenated Americans or not American at all. While the Ivy League officers perused Madison Grant’s 1916 best seller The Passing of the Great Race, which claimed that “the wretched, submerged population of the Polish Ghettos” was polluting the “splendid fighting and moral qualities” of America’s old “Nordic” stock, the draftees—20 percent of them foreign-born—traded ethnic insults and occasionally came to blows. Hyman never breathed a word of it in his letters home. What would be the point?

“No one is allowed to leave the barracks,” Hyman wrote home on December 10. “Whatever may turn up we are getting ready and are singing in the barrack our camp songs Pack up Your trouble in your old kit bag and smile smile smile and also Where do we go from here?” (The latter ends with the memorable refrain: “Where do we go from here, boys? Where do we go from here? Slip a pill to Kai-ser Bill and make him shed a tear, And when we see the en-e-my we’ll shoot them in the rear, Oh, joy! Oh, boy! Where do we go from here?”)

Around Christmas, Hyman returned home to Brooklyn on a three-day pass. He and Anna had one last date—dinner and a show in Manhattan. Back at Camp Upton a couple of weeks later, Hyman received word that Sam’s wife, Celia, had safely delivered twins on January 9—Dorothy and Sidney, a girl and a boy, the first great-grandchildren of Shimon Dov. Three days later, Hyman’s unit was finally issued their “complete field outfit”—rifle, bayonet, ammunition, mess kits, and metal water bottle. On January 17, they were ordered to assemble in the bitter cold at the rail platform for the train to Long Island City. Here they boarded ferries bound for a pier in New York harbor. Stowed like steerage passengers on the lower deck of a British troop ship—“We were just live freight,” wrote Hyman—they set out across the Atlantic. The crossing proceeded without incident until the final day, when, eight hours shy of Liverpool, Hyman’s ship collided with one of the freighters. Sirens wailed as passengers and crew were ordered to evacuate to lifeboats. “Here, I learned how men react in emergencies,” said Hyman. “Strong men prove to be panicky and weak men become strong, some cry, some pray, some sing. I was among those who sang. Normally, I don’t carry a tune.” Upon inspection, the damaged ship was deemed seaworthy—and so the weak and the strong, the tuneful and the teary, reboarded and steamed on to Liverpool. After a few days regrouping in dank unheated wooden-floored tents at a camp near Winchester, they boarded ships at Southampton and crossed the channel.

“Arrived safely,” Hyman cabled from LeHavre on the Normandy coast on February 3. “Feeling great love to all.”

He spent his first two months of war marching, training, and feeling sorry for himself because not a single letter reached him from the States. All the replacement recruits from Camp Upton were in the same boat: because they were constantly on the move, shuffled from unit to unit, neither their mail nor their pay caught up with them. “We began to feel we were all among the forgotten men,” Hyman lamented.

Finally, on March 10, 1918, his permanent assignment came through. The forgotten men were piled into dun-colored French rail cars—no American soldier failed to remark on the words “40 hommes, 8 chevaux” (40 men, 8 horses) prominently stenciled on the side—and transported to the city of Toul east of Paris. Hyman reported to Company K, 18th Infantry, First Division. The company’s commanding officer, Captain Joseph Quesenberry, a boyish twenty-three-year-old honors graduate and former football player from the New Mexico College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in Las Cruces (now New Mexico State University), informed Hyman of the great honor that had befallen him: he had landed in the fabled Big Red One. The First Division prided itself on being first in every way: it was the oldest division in the U.S. Army, the first American division to arrive in France after the United States entered the war, the only American division to parade through the streets of Paris on July 4, 1917, the first to fire a shell at the German line, and the first to suffer casualties. When Hyman and the other replacement troops fell into line at Toul, Captain Quesenberry laid out their sacred mission: “The First Division has been in every war the country was in. It came out with honors every time. I expect to maintain the good name of the division in this present conflict, so we can wear the Red One [the divisional insignia] with pride.” There was another First Division first that involved the captain personally—on March 15, he had participated in an attack in which the Americans took their first German prisoners of war. After bouncing around for five months, Hyman was at last in a permanent outfit with men who had “pride in their company, regiment, and division.”

Above all, pride in their commanding officer. “He was a great officer, a soldiers’ soldier,” Hyman wrote of Quesenberry. “He was the idol of our outfit.” The 250 men in Company K were ready to lay down their lives for their young captain. Hyman felt the same.

“There is no doubt that it will be a shameful peace,” declared the newly empowered Lenin when faced with the dilemma of how to extract Russia from the war, “but if we embark on a war, our government will be swept away.” The most the Bolsheviks could hope for was to minimize the shame. This they botched as well. Peace negotiations with the Germans opened in the city of Brest-Litovsk three days before Christmas of 1917 and culminated in a dramatic stalemate in the middle of February 1918. The Russian delegation under Trotsky announced that Russia was pulling out of the war but refused to commit to any kind of peace treaty. “Neither peace nor war” was Trotsky’s sly position. The Germans’ response was to mount a rapid push east into Russian territory. In five days, the German army advanced 150 miles, swallowing more Russian territory than in the previous three years. With Petrograd in imminent danger, the Bolsheviks moved the government to Moscow. On February 23, the Germans made one last ultimatum for a peace treaty, and Lenin conceded: “It is a question of signing the peace terms now or signing the death sentence of the Soviet Government three weeks later.” The treaty of Brest-Litovsk was formalized on March 3 and it was indeed shameful. Russia lost not only all of its western territories—Poland, Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, Ukraine, most of Belarus—but a third of its population, a third of its arable farmland, more than half of its industry, and nearly 90 percent of its coal mines. The dismembered former empire would devote what remained of its resources to a protracted civil war.

Rakov and Volozhin were now under German control. After three years near the front line and six months of lawlessness following the Bolshevik revolution, Shalom Tvi and Beyle were subjects of the Ober Ost—the German name for the territory they had taken from the Russians during the war. The regime change came as a huge relief. The family had lost everything during the chaotic “neither peace nor war” weeks in February, when a gang of armed bandits and deserters took over Rakov and terrorized the townspeople. “For three days they rioted, looted, and plundered, with no one to stop them,” one resident wrote. Sonia, now almost eight, and her two older sisters, Doba and Etl, were hidden away in a closet while the marauders went from house to house. Their mother crept into the garden at night to bury the family’s money and silver. Then, a week into March, the Germans rolled in and the reign of terror came to an end. The girls emerged from hiding. Beyle went to the market to see if there was any food for sale. Shalom Tvi salvaged what he could of their shop and factory. The family, like all of Rakov’s Jews, had high hopes from the Ober Ost. The provisional government had been powerless. The Bolsheviks had brought nothing but plunder and chaos. Maybe under the Germans life would return to normal.

And indeed for a while it did—or something that approached normal. German officers requisitioned rooms in the finer houses in town, but they treated the home owners, Jews and gentiles alike, with respect. Germans did not steal from Beyle’s garden as the Russian soldiers had. Shops reopened in the market. The peasants once again trundled into town on Monday and Friday, bought and sold, got drunk, and staggered back to their villages. Relatives of Shalom Tvi in a nearby shtetl had a German officer billeted in their house, and the daughter reported that he was a perfect gentleman who did everything he could to keep the family safe and comfortable. When Passover came on March 28, the German authorities made sure that Rakov’s Jews had kosher flour to bake matzo. Shalom Tvi was astonished when a couple of German Jewish soldiers showed up at shul for Shabbat services. Germany’s Jews were far more assimilated than Russia’s, and most of the German-Jewish soldiers who occupied the shtetlach were appalled by the poverty and backwardness of the Ostjuden—the Eastern Jews. But for a few, the life of the shtetl stirred some deep atavistic longing. “On the earth this is the last part of the Jewish people that has created and kept alive its own songs and dances, customs and myths, languages and forms of community, and at once preserved the old heritage with a vital validity,” wrote one German Jew serving with the Ober Ost.

After nearly four years of war, Shalom Tvi and Beyle did not expect much from their new rulers. The Germans were better than chaos and banditry—but they were occupiers, not angels, and they could be just as ruthless as the Russians when they were crossed. There were stories of German soldiers jeering at the Jewish townswomen whom they had forced to scrub a market square on hands and knees; and Germans giving Jewish laborers soup crawling with worms. “Jews are living here in considerable numbers: a cancerous wound of this land,” one German officer reported after taking charge of his district in the Ober Ost. Another officer declared that Jews were loathsome “because of the ineradicable filth which they spread about themselves.” A good German was better than a Russian, Shalom Tvi concluded, but a bad German was worse than anything. The German high command had had almost four years to impose Deutsche Arbeit—German Work—on the Ober Ost; by the time they took Rakov, they had their Germanizing policies down to a science. They restored order, but they also took all the best food, grain, and livestock and sent it off to Germany. “We ate what the [German] soldiers threw away, including potato peels from the military kitchen,” one boy wrote.

Shalom Tvi could not help noticing that Rakov’s German occupiers were hungry and ragged too. These were not the grinning, singing, strapping youths who had marched off to war in the summer of 1914—but an exhausted army of the very old and very young. Shalom Tvi had seen four occupying forces come and go in quick succession in the year since his father’s death. The Germans were tolerable as long as they lasted, but frankly, he was dubious that they would last long.

Shalom Tvi and Beyle’s youngest daughter, Sonia, was eight years old when the Germans entered Rakov. She retained no memory of the foreign soldiers marching into town, the new flags and posters, the punctilious officers, her parents’ cautious relief. What she did later remember from this time was being punished for setting foot in a church.

Sonia was a born adventurer, confident and curious; when her heart was set, she did what she wanted—even if it got her into trouble. One day late in the war, Sonia noticed crowds of people in their finest clothes converging on the Catholic church, just a stone’s throw from their house. Sonia slipped out the gate and followed the people up the lane. When she reached the church, she saw there was a wedding. One of the teachers at the Polish Catholic seminary was marrying a seventeen-year-old girl from a wealthy gentile home, and the celebration was large, noisy, and colorful. As the guests in their finery climbed the steps and disappeared into the big double doors beneath the pointed brick arches, Sonia decided she had to follow them. It was beautiful inside the church—far more beautiful and mysterious than Rakov’s cozy wooden shul. The ceilings were so high she had to crane her neck to see to the top, and there were paintings framed in gold wherever she looked—paintings of beautiful women and a sad suffering man. “It was so quiet there,” Sonia remembered, “with not even the sound of a fly buzzing around. The walls were covered with many different pictures of Jesus, the crucifixion, the resurrection, his mother Mary, and more. This was the first time I had ever entered a church.” But not all the images were lovely. Sonia noticed a knot of guests gathered in the shadow at the back. She crept over to see what they were doing—no one paid any attention to her, she was so small and quiet. “I saw that they were all spitting onto a certain place, and when I looked closer I saw the figure of an old Jewish man with a big nose, dressed in a red cape, labeled ‘The Traitor Judas Iscariot Who Betrayed Jesus.’”

Sonia fled from the church and ran home. She couldn’t help blurting out what she had done and seen to her parents. Her father was furious. “He said that it was forbidden to Jews to set foot in a church. I had to swear a neider [vow] of 40 days of silence.”

Forty days of silence—when the child felt like howling at the top of her lungs. But this was the vow that Jews in Europe had always imposed on one another: when you wanted to scream, keep your head down and your mouth shut; don’t look; don’t fight back; hide.

Sonia could not understand what she had done wrong. “It was simply that it was very interesting to me to see inside,” she said. Wasn’t it punishment enough to discover that in their church the Christian neighbors secretly spat upon the dirty Jew? She wondered if they spat on the gates of her own house while their backs were turned. She couldn’t fathom this hidden hatred. It didn’t seem right that their churches had domes and steeples and stained glass and pictures framed in gold while everything Jewish was so shabby and sad. Even the Christian cemetery was a gardenful of flowers, while the Jewish cemetery where her grandfather was buried struck Sonia as a place of “total destruction, poverty, and the feeling of exile—that’s what I felt.” Sonia was once walking through the Christian cemetery when her eyes fell on an inscription in Russian—I’m already home, you’ll come to visit soon. She wondered what it could possibly mean. The Christians had a home right here on earth—why did they need another? In Rakov’s Jewish cemetery, the cemetery of exile, trees grew but not a single flower bloomed. When her father went there to pray for her grandfather’s soul, he stood outside the rusted fence like a beggar. Why couldn’t a Jew have sweetness and beauty too?

At the end of March 1918, around the same time that Rakov was absorbed into the Ober Ost, the Germans launched a massive push aimed at decisively ending the stalemate along the Western Front. The Americans had still barely gotten their noses bloodied in the war: now that the spring offensive had put the Germans within striking distance of Paris, the time was at hand for the Americans to show what they were worth. The First Division was chosen to mount the counterattack, and on April 6, 1918, Sonia’s first cousin Hyman boarded one of the hated “40 hommes, 8 chevaux” train cars and headed up to the front line in Picardy. On the train ride across northern France, Hyman saw smooth round hills just greening up in the first flush of spring and blackened stumps of villages that had been shelled to oblivion. He saw women and children, sometimes waving, sometimes staring stonily; he saw men, but only old men or young ones who were bandaged or missing limbs. He saw church steeples and hedge-rows and delicate jade green fronds that by summer would explode in drifts of red and pink poppies. He detrained in a sector that looked a lot like the countryside around Rakov, only hillier. He scrambled to find places to sleep. He listened to the rumors of imminent attacks. He pined for letters—“I have not heard a word from anyone since I left the States,” he wrote his parents, “days have turned into weeks and weeks into months and even the months are turning and turning and still not a word from any one of you.” He pined for Anna. He became a crack marksman with a Springfield bolt-action rifle.

On the night of April 24, Company K took up its position about a mile from the village of Cantigny. Hyman, scoping out the terrain, understood at a glance what they were up against: the Germans had chosen an elevated position on the top of a chalk rise that commanded the countryside to the west. When it came time to fight, Company K would be slogging uphill without any cover into the teeth of German machine guns.

But first they had to survive the ceaseless barrage of German artillery. As soon as the regiment dug in near Cantigny, huge volumes of high explosive shells and canisters of poison gas rained down on them from some ninety German battery positions. German airplanes whined overhead, spitting down rounds of machine-gun fire. “The shelling did not come in bursts,” wrote one soldier, “but was continuous and apparently was meant to break down the morale of the new occupants of the sector.” Food carts were blown up or held back by the intense shelling, and the men counted themselves lucky to get one cold meal a day. For a week they lived on “a slice of meat, a spoonful of sour mashed potatoes, a canteen of water, a canteen cup of coffee, a half-loaf of bread, a beautiful country and sometimes a sunny sky.”

On the evening of April 27, German shells started landing with such deadly accuracy that Captain Quesenberry decided to move his men to a safer position. It was either move or get blown up. Around eight o’clock that night, the men were engaged in digging a new trench in a less exposed position when the shell with the captain’s name on it came in. Quesenberry had listened to a thousand shells whistle and detonate—but this one was different. The shriek was directly overhead; the flash was blinding; the concussive blow immediate, deafening, and suffocating. On contact, the high-explosive shell casing disintegrated into a thousand hot splinters of steel. Some of these splinters tore into Captain Quesenberry’s arm and leg.

“We held our position,” wrote Hyman, “but Captain Quesenberry, the idol of our outfit, was hit and severely wounded.” A soldier with Company K who saw Captain Quesenberry fall testified that “he was taken away in an ambulance and I understand died on the way to the hospital, from loss of blood.” But Hyman gave a different account:

Four of us carried him into the church basement of the town, which was now a field hospital. We found many of our men lying there waiting for first aid and evacuation. The medics seeing the captain attempted to give him first aid. He refused treatment and ordered the medics, “don’t touch me until all my men are treated.”

The army’s Graves Registration Service recorded that Captain Quesenberry died of shell wounds on April 28, the day after he was hit. The twenty-three-year-old captain was buried in the temporary American military cemetery at Bonvillers, though later, at the request of his father, his remains were disinterred and returned home to Las Cruces.

The men of Company K carried on without their beloved captain. For a month they endured ceaseless pounding outside of Cantigny. Then, on the morning of Tuesday, May 28, they were ordered to take the village. It was Hyman’s first taste of combat. At the dot of 5:45 A.M., the combined French and American artillery opened up with everything they had and blasted away for an hour. When the guns fell silent, whistles shrilled up and down the line and the infantry moved out in waves toward the German stronghold. By 7:20 A.M., the Big Red One had taken Cantigny. The hard part would be fending off the inevitable German attempts to take it back.

Hyman’s unit was supposed to form “working and carrying parties” to supply ammunition and water to the units at the front of the assault. Hyman remembered it like this: “Our company was ordered to get to the top of the hill and dig in. Make no advances. Just dig in and defend our position. Our company reached the assigned positions. We lost many of our buddies while digging under fire.” These heavy casualties occurred during the ferocious counterattacks that German forces began mounting around 9 A.M.—seven counterattacks that went on for two days. Company K’s carrying parties made easy targets as they tried to run supplies to the front; their losses mounted quickly.

“We were under continuous fire,” wrote Hyman. “The German Army tried to retake the position, but our regiment held on. Cantigny was ours, and remained so.”

Though it looked like an insignificant knob on the map of the Western Front, Cantigny was a jewel much prized by the German high command because it represented the westernmost point on their line—the deepest they had penetrated into French territory. Paris was a mere seventy miles away. A German victory there would not have significantly altered the course of the war, but it would have dealt a stinging blow to American morale. The First Division made sure that that did not happen. They paid a stiff price, but in the end, the Americans fought off the ferocious German counterattacks and prevailed. Captain Quesenberry was dead, many of his men were killed or wounded in the course of the battle, but Hyman and the boys who remained held their position—and the Big Red One held Cantigny.

When new recruits were rotated into Company K to fill the places of those who had fallen at Cantigny, Hyman had bragging rights. He had been there first. He had acquitted himself honorably in the first major American engagement of the war, and the first victory of the First Division. A decade earlier he had been tinkering with watches in the Russian Pale. Now he was a warrior.

Two months later, the 18th Infantry saw action again at Soissons. It was Hyman’s last battle in the Great War.

Hyman had always admired square-jawed, starched-collar, old-line WASPs—and his new boss was a prime specimen of the type. Six feet tall, ramrod straight, broad chested, and steely eyed, Colonel Frank Parker, commander of the 18th Infantry, was a son of coastal South Carolina, a graduate of West Point, a gentleman and a scholar who spoke fluent French and taught young soldiers the art and science of modern war. He was also, apparently, one hell of an inspiring leader. Colonel Parker certainly inspired Hyman on the morning of July 17, when he stood in a clearing in the Compiègne Forest surrounded by his regiment—3,500 strong—and exhorted his men to fight and die:

Men, tomorrow we go over the top. Back home the war is a fight for the survival of Democracy. You just forget it. Tomorrow you and I fight for our own lives. Those of you who have no will or desire to live can start out by giving your life away. My advice is to go out and fight for your life and the lives of your buddies alongside of you. Starting tomorrow the whole world will be watching our activities. God be with you.

Hyman had no idea on that July morning that he was about to be marched into the battle that turned the tide of the war. “You in America know more about the war in one day [from reading the newspapers] than we soldiers find out in a whole month,” Hyman wrote the family back in Brooklyn. Men on the ground are seldom aware that they are making history, but history would be made in the wheat fields at Soissons in July 1918.

During their spring offensive, the Germans had punched a salient—a bulge—in the line between Soissons and Reims, from which they hoped to storm the Allies’ ranks and march on Paris. At this weary stage in the conflict it was little more than a desperate gasp of hope and both sides knew it. But the Marne Salient had been stuck like a thorn in the Allies’ side. The longer it remained, the more it goaded them. In July, the Allied command decided the moment had come to extract the thorn and start pushing the Germans back to their own borders. The First and Second American Divisions, along with the First Moroccan Division (which included the French Foreign Legion), were handpicked to do the job. Parker’s 18th Infantry would spearhead the push. “No more glorious task could have been assigned to any troops,” one of the regiment’s officers declared.

Hyman set out for the front with a full pack at dusk on July 17. Within minutes it was pouring down rain. Men, horses, mules, and transport vehicles became snarled in an epic jam on the narrow muddy French roads:

Blinding flashes of lightning illuminated the countryside momentarily and gave the moving columns of men glimpses of a scene such as they would witness only once in a lifetime. Every road, every track and every field was filled either with trucks, wagons, artillery or moving columns of men. Here and there the French cavalry could be seen threading their way through the maze of tangled men, trucks and animals. . . . Clothing, packs and equipment of all kinds were soaked until they added many extra pounds for the men to carry. Strange oaths of the Orient mingled with those of Europe and America.

In one burst of lightning the serene neoclassical façade of the royal Château de Compiègne appeared at the end of a long straight line of trees and then vanished: a glimpse of heaven in the midst of hell. The sky cleared before dawn and by first light Hyman stood blinking and shivering in the crossroads village of Coeuvres—two intersecting streets packed almost wheel to wheel with rows of French artillery. There was to be no preliminary shelling. It was so quiet Hyman could hear birds heralding the dawn. At the dot of 4:35 a French artillery captain gave the signal to lay down the first salvo of the rolling barrage and two thousand big guns opened up simultaneously. The divisions to the south did the same thing at the same time. A thirty-mile wall of fire blazed, died, and blazed again.

Hyman understood that his time had come. Crouched like a boxer stepping into the ring, he gripped his Springfield rifle in both hands and moved out. About a thousand infantrymen fanned out in the first wave. Once Hyman cleared the scrubby woods around Coeuvres, he was in open wheat fields—fresh golden waist-high grain swaying in the morning sun for mile after mile on rising ground. A beautiful sight to behold if it weren’t for the sudden flash of machine-gun fire and the black fountains of dirt that spouted where German shells detonated. Every now and then Hyman heard a cry and then a pockmark appeared in the wheat where one of the men fell and bled. By noon the wheat in every direction was speckled with dots of moving khaki and littered with pockmarks. Hyman kept moving ahead. The German fire was too intense to evacuate the wounded—as for the dead, they swelled and blackened in the summer sun until the battle was over and the chaplains and burial details could tend to them. Hyman didn’t stop; he tried not to look at the wounded or hear their pleas for water. His orders were to go forward into the bullets and bombs. He fired his rifle when he had a target, ducked his head instinctively at every explosion, crawled on his stomach through the wheat when a burst of bullets came, and rose again to put one foot in front of the other. Even though every fiber of his being wanted to turn and run, he advanced. He had had no sleep and precious little food for thirty-six hours. Adrenalin kept hunger and the dull ache of sleeplessness at bay—adrenalin and fear. “No man is fearless in battle,” wrote one of his comrades of that day, “but most well-trained soldiers hide their emotions.” Hyman had lived through Cantigny. He hid his fear and pushed on.

July 18, the first day of the Battle of Soissons, was long and grueling. German resistance stiffened through the morning hours. Enemy machine guns spat at them from every rise and from behind every stone farm building. Casualties mounted. In their few months of combat, Americans had learned to hate German machine gunners. Word was that Boche officers ordered their machine gunners to chain themselves to their weapons and keep shooting until they were killed. They mowed down your buddies in perfect rows and then, when you were about to take them out, they jumped up with their hands in the air shouting “Kamarad!” Even though artillery killed more men in the Great War, machine guns aroused more fear and rage among the troops.

Through the endless hours of daylight, Hyman listened to the peculiar “zeep-zeep” of machine-gun bullets whizzing past him “like insects fleeing to the rear.” That night, he bedded down in a shell crater for a few hours of sleep, and the next day he and the other guys who had made it through were up and at it again. Captain Robert S. Gill, who had replaced Joseph Quesenberry as commander of Company K, told his men they had advanced farther into hostile territory than any other unit in the sector. Now they had to do it all over. Their objective—the heights of Buzancy, south of Soissons—was still seven miles away.

The second day, July 19, went badly. Resistance was ferocious, forward motion painful. Those German machine gunners were living up to their reputation. Hyman and his comrades in Company K were now so far out ahead of the rest of the division that they were taking horrific flanking fire from the left. Cover was all but nonexistent in the wheat. By day’s end, 60 percent of the regiment’s officers were gone—dead, wounded, missing, captured—and nearly all the noncommissioned officers (the corporals and sergeants who were in charge of the individual platoons) had fallen. Even doughty Colonel Parker, shaken by the number of casualties, begged to be relieved. Another officer complained that his men were “so exhausted . . . that it was often necessary to take hold of them and shake them to get their attention.” But First Division commander Major General Charles P. Summerall was implacable. The assault continued.

July 20, the third day, fell on the Sabbath. Hyman was still in the wheat. He was still being savaged by machine-gun and artillery fire. Sometime in the course of that bright hot summer day Hyman’s luck ran out. He was gassed with mustard.

They called it mustard because it reeked of garlic and mustard, and they called it a gas, but in fact mustard gas is a thick oily amber-colored liquid like toxic molasses that volatilizes above freezing. Of the three types of poison gas introduced during the Great War, mustard was the most insidious, the most excruciating, and by far the most lethal. It was delivered in glass bottles packed inside artillery shells: when the bottle burst, the mustard escaped and transformed itself into a heavy vapor that crept along the ground and oozed into trenches and dugouts. By the time Hyman smelled the reek and got his gas mask on, it was too late. Mustard, as Hyman quickly discovered, did not have to be inhaled to inflict pain and injury and death: the gas ate at any piece of flesh it came in contact with, inside or outside his body. The vapor fixed itself to the sweat on Hyman’s neck and raised excruciating blisters that swelled and broke and wept plasma for days and refused to heal. Had he not been wearing his mask, the mustard would have blinded him and flayed away his bronchial tubes. Men who inhaled it vomited and bled internally; they choked and gagged and gasped for breath. The pain was so intense that victims had to be strapped to their beds or they would tear at themselves or bash their head against the wall. The oily vapor saturated clothing and refused to dissipate, so doctors and nurses were gassed with mustard when they treated soldiers who had been gassed. Those who died suffered for a month or more before death released them.

Hyman never talked about the agony he suffered. “On the third day, we were attacked with mustard gas,” he wrote later. “I became a casualty. Taken to the field hospital, put in an army ambulance to a railroad station; put in a hospital train and sent to a French hospital in the city of Angers, far from the front.”

The Battle of Soissons raged on without him for one more day. At the end of Sunday, July 21, the fourth day of fighting, the American soldiers still in action accomplished their mission of cutting German supply routes at the neck of the salient and driving the Germans back to a line running south from Soissons; the German retreat from the salient would continue for another month. Soissons was chalked up as a success—but the price was ruinous. A thousand men in the regiment’s Third Battalion had gone into battle alongside Hyman on the morning of July 18; only seventy-nine returned when the regiment was withdrawn on July 22. The First Division Infantry as a whole suffered casualty rates (dead, wounded, gassed, missing) of 50 percent, and 75 percent of the infantry’s field officers were knocked out. “The flower of the American Army had been cut to ribbons,” wrote one soldier in the regiment.

The generals, however, had cause to celebrate. For the first time since September 1914, the German high command had ordered a general retreat. Appalling as the casualties were, Soissons proved to be the beginning of the end of the war.

For Hyman, the war was over. “It would be foolish for me to say that I am well for this letter is written in a Hospital,” he wrote home on July 22. Two days later, he elaborated a bit—though he was clearly distraught and disoriented. “I am not well enough just now to go under the same strain that I was under recently while at the front. . . . I lived through days that a fellow does not have to make [illegible] to remember and if God will be as kind to me in future operations, as he has been in the last, then [these] days will always live in my memories.” Whatever memories he carried, Hyman never again wrote or spoke of them. “What’s done is done,” he told the family.

The blisters raised by the mustard gas eventually closed and healed, though he would always have scars on the lower part of his chin and on his neck behind his left ear. Hyman remained in French military hospitals long enough to get thoroughly bored and restless. While nurses changed his dressings, he argued with the other wounded guys about which American state was the best (“I certainly have a heck of a time when I tell the Westerners and Southerners that New York is the only place”). In September he was well enough to go to Yom Kippur services. He boasted in a letter to his parents that “it is a known fact the First Division has done wonderful work.” It shamed him that the division was still in combat while he convalesced behind the lines. Indeed Company K, its decimated ranks filled out with replacement soldiers, fought at Saint-Mihiel and the Argonne, the massive American engagement that brought the war to an end on November 11, 1918.

Hyman finally returned to the States in February 1919. He went back to work in the business, married Anna, fathered two children. But in ways that counted, ways he would never speak of, Hyman’s life was not the same. He had been in war. He had seen men get torn apart by exploding shells and bleed to death in a wheat field; he had marched into machine-gun fire and shot his rifle at enemy soldiers; he had been burned and scarred by poison gas. Hyman had passed a test that every man wonders about. His uncles and cousins in Russia had endured occupation and revolution, but they had not been in the army; his brothers in America had spent the war building the business. Hyman alone had worn the uniform. It wasn’t his choice to be a soldier. But he did his duty and was proud that he had. “What’s done is done,” Hyman said when his family asked about the war. But that wasn’t the whole story. To soldiers like Hyman—Jews, immigrants, naturalized Americans—the war made a critical difference. They all knew the stereotypes—pants presser, watchmaker, pale-faced scholar, slacker, coward. They knew the skepticism of the likes of Captain Quesenberry and Colonel Parker and Major General Summerall. Is it possible to make soldiers of these fellows? Hyman had seen for himself the new respect in the eyes of his officers and comrades after he returned from battle. It was a point of honor that the percentage of Jews in the U.S. Army was higher than in the civilian population. Two thousand American Jews were killed in action in the Great War; Jewish American casualties topped ten thousand; 72 percent of Jews in uniform served in combat units. Sarah had been devastated when her son was drafted, but she wept tears of pride when he came home to Brooklyn safe and mostly sound. Hyman’s service bound the entire Cohen family more closely to America. One of their own was a Doughboy. When the Purple Heart—the American military medal bestowed on those wounded or killed in action—was reinstituted in 1932, Hyman was awarded one retroactively. He wore it proudly all his life.

It was different for the children and grandchildren of Shimon Dov who remained in the Old Country. An armistice was declared, a treaty was signed, but in Rakov and Volozhin, revolution and civil war continued. Indeed, the treaties that formalized the cessation of hostilities in 1919 proved to be less the end of the Great War than the beginning of the next one.