CHAPTER FIFTEEN

SECOND WORLD WAR

Doba was still a young woman—only thirty-seven years old—in 1939, but she was emotional and high-strung and a bit of a hypochondriac. Motherhood, her greatest joy, was also the source of endless upset, which no doubt contributed to her attacks of nerves and ill health. If Shimonkeh or Velveleh so much as skinned a knee, Doba flew into a passion; when Shimonkeh nearly died of scarlet fever the summer Sonia made aliyah, no one could breathe a word to pregnant Doba, lest she become unhinged. With so much angst fluttering her heart, Doba was forever craving rest and relaxation. When her in-laws offered her and Shepseleh and the boys use of a cottage that they had rented in the spa town of Druskininkai that summer, Doba jumped at it. Druskininkai’s mineral baths were renowned; the country air would do all of them good; there was a hammock stretched between two trees where they could take turns snoozing on warm afternoons. Doba decided that she would spend the entire summer there and, after some cajoling, she prevailed on her mother to join her. After all, Shalom Tvi was in America and the leather business had been sold, so for the first time in her life Beyle was free to leave Rakov and do what she wanted. What better occasion for a nice long stay in the country?

Beyle joined Doba’s family at the spa right after Shalom Tvi’s departure at the start of July and stuck it out at Druskininkai for as long as she could stand it. She took the waters; she tried to sleep in the hammock; she sat in the shade; she watched Shimonkeh, now eleven years old, ride his bike and Velveleh, seven, sit with his father and move wooden pieces around the chessboard. She wrote letters to her husband and bustled around the kitchen. She went to shul on Saturday with Doba. But five weeks in, Beyle decided that she had had enough. After more than forty years of hard work, idleness did not come easily. She wanted to be home. It was arranged that Beyle would depart and that Etl, Khost, and Mireleh would take her place in the Druskininkai cottage for a few weeks’ vacation. By August 21, Beyle was back in Rakov writing to Sonia and Chaim about how healthy she felt after taking the waters and how glad she was that Etl’s family had a chance to relax at the spa before Khost started another busy year teaching school.

It was only because Khost was away in Druskininkai that he avoided being called up by the Polish army when the Germans attacked on the morning of September 1.

With the outbreak of war, there was no question that they must leave Druskininkai immediately—but where should they go? The two couples sized up the situation anxiously. Clearly, Etl and Khost would return to Rakov—Mother could not be left alone and Khost had a job there. But what about Doba, Shepseleh, and the boys? Wouldn’t it be better for them to come to Rakov too so the family could all be together? They didn’t have long to debate it—they must get out before the roads became impassable and the rail lines were bombed. In the event, they decided that their two families should separate, reasoning that if they were in different places they would have a better chance of keeping some line of communication open with Sonia in Palestine and Father in America.

The little rail station outside of Druskininkai was pandemonium, but somehow the two couples shoved their children and luggage onto separate trains and somehow the trains got through to Vilna and to Olechnowicze, the station closest to Rakov. Thank God, they thought, that Rakov and Vilna were in the east of Poland, far from the Nazi invaders. (Rakov and Vilna had been incorporated into the newly formed Polish state in the 1920s, so when the war broke out, the members of both families were Polish citizens.) Thank God that on September 3, Britain and France declared war on Germany. Thank God that Poland had an army, an air force, tanks, modern weapons, the will to fight. Doba wept with joy when they opened the door to their flat near the Dawn Gate and saw that all was exactly as they had left it in June.

Then came the first German bombing raids. Sirens wailing in the street—screams and shouts in the hallway—the pounding of shoes on the stairs as the neighbors fled to the cellar. Doba and Shepseleh leapt out of bed, woke the boys, and fled downstairs with the others. They cowered in the dark and strained their ears for the thud of explosions. They huddled together trembling until the all-clear sounded. When they returned to their flat, their hearts were racing, sleep impossible. In the morning, Doba and Shepseleh dragged themselves out of bed hollow-eyed and desperate for news.

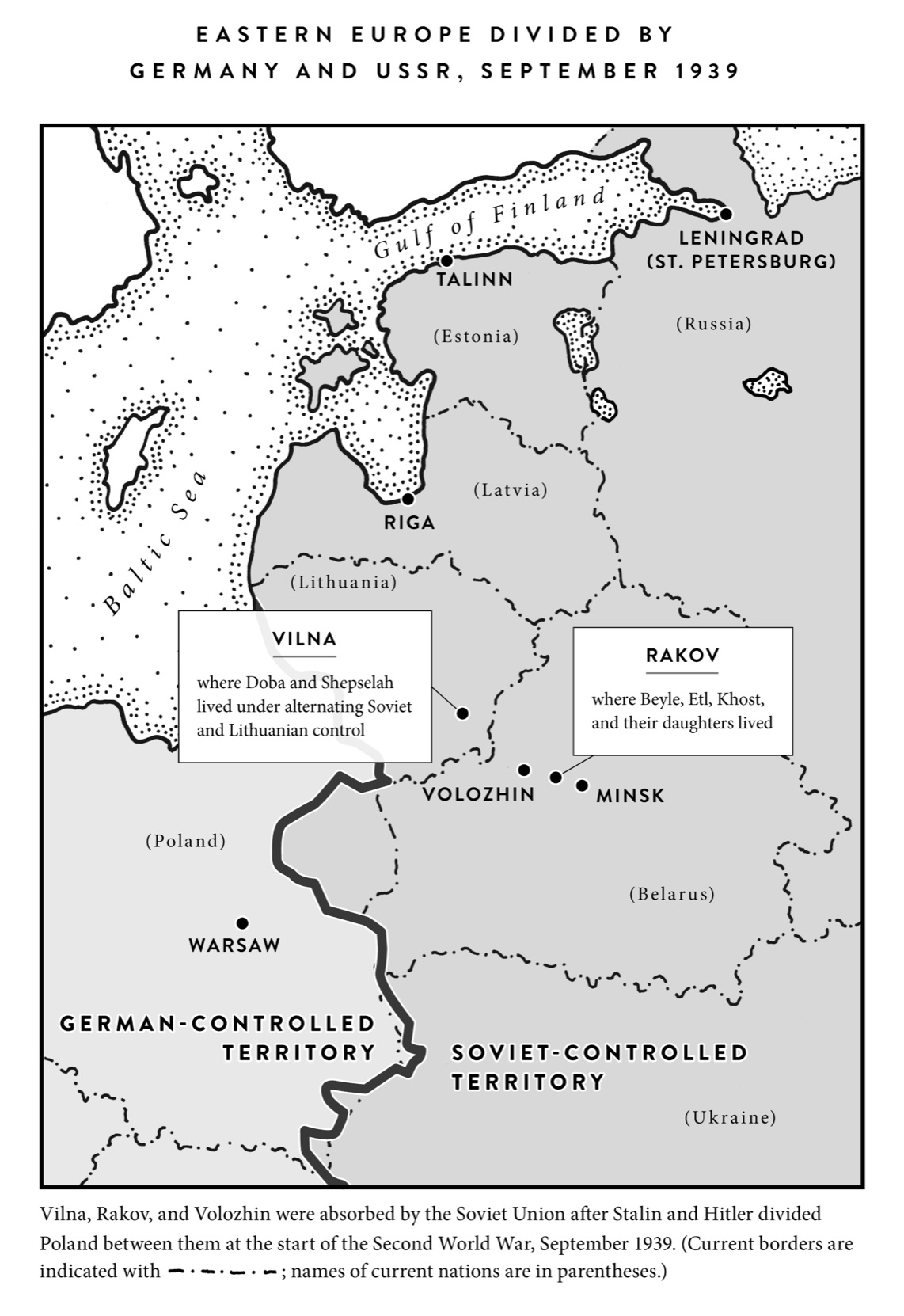

It came thick and fast in those September days and none of it was good. Britain and France were technically at war with Germany but they did nothing to help Poland. The Polish retreat from the western border had turned into a rout. The Wehrmacht seemed to be everywhere and unstoppable. The Luftwaffe dominated the skies. By September 14, Poland’s air force had been effectively disabled. Sixty German divisions were converging on Warsaw, and German planes, unchallenged, were bombing every major city in the country. In the general mobilization, Khost was called up for service with the Polish army. (Shepseleh, though subject to the draft as a citizen of Poland, was spared.) Etl had no idea where her husband was being sent or when he would return. The news that arrived on September 17 baffled all of them: the Russians were now attacking Poland from the east. Evidently, the Nazis and the Soviets were allies in this new war—it made no sense, but that’s how it was. Only later did it emerge that Hitler and Stalin, by the terms of a secret nonaggression pact worked out by their foreign ministers, Ribbentrop and Molotov, at the end of August, had agreed to carve up Poland between them. Hitler took the west, including Warsaw, Lodz, Cracow, and Lublin; Stalin got the east, with Lithuania thrown in as a “Soviet zone of interest.” In this new division of Poland, Rakov was Russian once again; and Vilna, which had flown God knows how many flags in the past twenty years, became Russian again too, at least for the time being.

As quickly as it started, the war seemed to be over. The bombing stopped in Vilna. Blackout curtains were removed; street lamps were lit again at night. Shimonkeh and Velveleh slept all night in their own beds. Polish troops started to trickle back, many passing through Vilna on their way home. “I cried when we saw soldiers returning and Khost was not among them,” Doba wrote her father. She and Shepseleh feared the worst, but God was merciful.

November 28, 1939

Dear Father,

I have much to tell you, but it is hard to do in a single letter. I have written to you before that Khost had been drafted to the Army. Now I can tell you that he has come back—first to Vilna and from here he returned to Rakov. You cannot imagine how happy we were when we saw him.

He was lucky. He was with us at Druskininkai and therefore reported for duty a bit later. That changed the whole situation. Shepseleh worried that if “the big ones” [i.e., the Russians] had not come, his fate would have been the same. The fact that we can joke about it is a good sign. So you don’t have to worry about our men, or the rest of us. We were very glad to see the “big ones” because we had been weary of staying days and nights with the children in the basement.

The real problem now is that there is not enough money. Zloties [the Polish currency] are worth nothing. Shepleseh does not have work. The office has shrunk. Only a few workers were left and it is hard to find work. The big firms are no more. Everything has changed suddenly.

Who could imagine that such a situation could ever happen? Briefly, dear father, we are left with no means of livelihood. What I have written is only a drop in the sea. What you read in the papers is nothing in comparison to what has happened here in only three weeks.

I envy the Americans their peaceful life. They cannot fathom what is happening here and in the rest of the world.

Love, Doba

The situation in Vilna remained volatile. The Soviets had seized the city on September 19, two days after they invaded Poland, but they agreed to turn it over to Lithuania at the end of October on the condition that 20,000 Red Army troops be permitted to remain in Soviet bases on Lithuanian soil. In the final days of the Soviet occupation, civic life collapsed. The Forward reported that “Vilna is congested with refugees and its population suffers hunger and privation; economic life has come to a halt and many Jews wander the streets begging for a piece of bread.” The Soviet pullout triggered a three-day pogrom. Vilna’s Polish and Lithuanian population beat Jews in the street, wounding 200 and killing 1; scores of Jewish shops were vandalized; a policeman was killed. A typhus epidemic broke out and hospitals overflowed (Lithuanians claimed that disgruntled Poles had triggered the epidemic by cutting the city’s water supply, while Poles insisted that Volksdeutsche—German nationals residing in Vilna—had connected sewer pipes to the municipal water supply). Meanwhile, 14,000 Jewish refugees from Poland’s German-occupied sector streamed in—among them “the spiritual elite of Polish Jewry” including 2,000 halutzim, 2,440 rabbinical students, 171 rabbis, and assorted Bundists, teachers, journalists, and scientists whom the Nazis had expelled. The refugees survived on charity distributed by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (“the Joint”), but Vilna’s non-refugee Jewish residents were on their own. “The food supply is being rapidly depleted,” wrote one resident. “One must brace oneself to acquire a little butter and some eggs. The queue for these items is enormous. . . . It is pointless to join the queue at 6 A.M., for by that time thousands wait at the door.” White-collar workers who had been accustomed to conducting business in Polish, Russian, and Yiddish were laid off in droves because they could not speak Lithuanian, the new official language. Shepseleh, now forty-two years old, joined the ghosts who haunted the streets looking for work.

My dear Father-in-law Shalom Tvi,

The big problem is that it is hard these days to find work. I traveled to Kovno [the Yiddish name for Kaunas, Lithuania’s second-largest city and the temporary capital during the interwar period] to see if I could find something. I spent money for the trip but found nothing. All the big companies have lost everything, and there is no one to turn to. Of course, the idleness causes the money to dwindle away and the cost of living has gone up. We still have food and do not suffer, but when I think of the future, I feel like my brain is exploding. To stay sane and healthy, it is better to not think too much. Who knew that the situation would deteriorate so fast?

You know, father, that I am not one to make life difficult, so if I allow myself to write to you like this, it shows that I am totally broken. Though truthfully, others have bigger problems. There are people who were well-to-do in the past who have no roofs over their heads. There are those who have lost a relative. So we should be satisfied with our lot and not complain.

Father, please write to us in detail about yourself, about Reb Avram Akiva and his family and about Hayim Yehoshua and his family. If you have not yet received our letter, I am reminding you that the money you sent has arrived and we thank you and uncle from the bottom of our hearts. Write to us what is happening with the visa. We can no longer take care of it from here. Maybe you can handle it.

Your son-in-law Shepseleh

For the family, there was one ray of light that dark season: on November 28, Sonia gave birth to a son. They named him Arie, for Chaim’s late father, though they called him Areleh as a baby and Arik when he was older. As he grew, no one could understand where the child had come by his looks—bronze, athletic, chiseled, a lanky golden boy in a short dark family. It was as if some warrior gene, after skipping many generations, had surfaced under the fierce Mediterranean sun.

“Mazal Tov, Mazal Tov, with God’s will may the tender born son bring luck, blessing and peace to the world,” Shalom Tvi wrote his daughter and son-in-law from New York. “May you raise him easily and may he merit a long life.” Shalom Tvi sent Sonia not only blessings and prayers but a steady stream of packages—hand-me-down clothing from the rich American relatives (“here one wears clothes a few times and then they discover a new fashion, discard the garment and buy something new”), money, even the occasional brooch or necklace. Sonia’s insistence that she had no need for jewelry puzzled her father. “Is it forbidden to wear jewelry there?” he demanded. “Surely women in the big cities wear jewelry even in Palestine.” Jewelry was the last thing on Sonia’s mind in those days. She had a toddler, not yet five, and a newborn but no refrigerator; their cow ate voraciously but provided only a trickle of milk; she worried about Arab attacks every night when Chaim drove the truck and was late getting home. We’ll come when it’s quiet, her mother and sisters used to reply when Sonia urged them to join her in Kfar Vitkin—quiet was their euphemism for peaceful, free of violence—but it was never quiet in the Land. Now Europe wasn’t quiet either. For as long as this war lasted, Sonia knew there was no hope of getting her mother or sisters out of Poland and into Palestine. She was on her own with two small children, a stingy cow, a tiny house baking in the sun, meat and cheese spoiling in the heat, an antiquated ringer washer, hostile Arabs over the next dune, and the cowardly British government that valued oil more than human life.

So no, Sonia was not thinking about jewelry when Areleh was born in the dwindling days of 1939.

Many years later, when she had children of her own, Leah asked her mother why she had spaced her children at such long intervals. Nearly five years separated Leah and Arik, another five and a half years passed before a third child was born, and yet another five years before the last one—four children in all spread out over sixteen years. “We waited because we were poor and there was so much work to do,” Sonia told her daughter.

“We met some wise people who are aware that we are sitting on the mouth of a volcano,” Doba wrote her father as winter closed in on Vilna. “Anyone with means has already escaped from here. Dear father, we must do something so that we can all come to you [in New York]—Mother, Etl, Khost, Mireleh. We are not interested in going to Eretz Israel, as you suggested. It is not quiet there. We simply don’t have the strength to go through a third war.”

Doba saw what was going on in Vilna—the refugees lining up for bread at the Joint; prominent lawyers, wealthy businessmen, distinguished congregants from Warsaw in rags, subsisting on handouts; men like her husband broken and despairing. Escape to New York now seemed like the only hope. “We have a joke about the refugee situation,” she wrote. “Everyone is laughing and saying that it pays to become a refugee, because at least someone takes care of them.” Doba was high-strung and hyperbolic—but she wasn’t foolish. She knew what was burning inside the volcano. She had a friend named Marisha whose husband had been taken by the German army at the start of the war and had not been heard from since. Four months without a letter—who knew whether he was still alive? Doba heard the rumors that the refugees brought with them—about the seizure and burning of Jewish homes and businesses in Warsaw and Lodz; about the sudden disappearance of able-bodied Jewish men. The Germans moved in and the next day the men were gone: rounded up, imprisoned, deported, God knows what. Doba wouldn’t talk about it, but she knew how close it was.

Winter came and the weather turned savagely cold. For days on end Doba refused to set foot outside the apartment. The boys quit going to school on the coldest days and stayed in bed under their feather quilts—it was cheaper than paying for extra coal. Velveleh was still jumpy from the German bombing raids. If a door slammed or a book fell he startled and trembled. Shimonkeh, a year away from celebrating his bar mitzvah, was growing tall and serious. What kind of future could she give them? Doba watched the luckier neighbors pack up and leave, and she envied them. Someone had sent for them. Someone had paid their way. Someone had arranged their papers. Why not her family?

Doba was tenderhearted. It was not in her nature to heap scorn, to recriminate or lash out. But as the first winter of the war dragged on, she began to seethe. It made her crazy to see others heedlessly enjoying what she and her children lacked. No one she knew enjoyed more than the American relatives. They became the focus of her fury. She blamed them for being rich while she and her family were poor, for being comfortable while they were suffering, for not doing more to help them.

Every week, Doba wrote to her sister in Palestine and her father in New York. Every week, her letters grew more bitter:

January 17, 1940

Dear Father,

It is good that you are not here. If you were home you would have suffered.

Who could have imagined that so horrible a war had begun? You were able to see Warsaw [before leaving for America], but now Warsaw is all in ruins. Tens of thousands were killed and woe to the few Jews who remained. What we didn’t see in the previous war we are going though in this war.

January [date missing], 1940

Dear Sonia,

The truth is that father’s stay in the USA is a big deal for us. He sees to it that the family sends money and help to us. But we are such egotists that it does not satisfy us.

I do not understand to what extent the family [in the United States] wants to bring us to them. If they wanted us, they would begin to arrange the papers because it takes a long time, but when one does not work on it nothing will happen. Why doesn’t Rosenthal make an effort? Everyone who has even a distant relative in America does all they can to get them out of here. But we have a wealthy family, and they prefer to send money instead of inviting us. Write me what you think about this.

You know that my heart is bitter. I am angry with the family and cannot understand why they have not sent all of us an invitation to come to them.

Dear Father,

I wish at least that William Rosenthal would be interested in us and help us survive in these hard times. A person needs hope. We received some money for food, but that is all the money we have. The Joint helps the refugees in Vilna but we have a family who can help us. Rakov is already barred and we can’t get any money from them. God forbid that we should be refugees. Doesn’t the family over there want us? Why do they remain indifferent in these hard times? They are waiting and this is a great mistake.

February 12, 1940

Dear Sonia,

Father said that a family like ours needs $50 to $60 a week [to live in America]. It will be hard to make a living [in New York] because Shepseleh does not know the language. We are still young and we can learn the language if we have to. Of course, it will be hard at first, but it will be very good for us. But they don’t care so it will never happen. In my opinion, if it were not for father, we would never have received even this money.

February 19, 1940

Dear Sonia,

Father allowed me to understand that they will never invite us. Too much of a burden for them. I don’t want to ask. It is enough that father needs to ask them for money to help us. It is very cold and the children spend the whole winter in bed. Thus we pass the days, while in America when it gets too cold for them they go to Florida.

Dear Sonia,

As the holiday [Passover] nears I see how our family is torn. There are moments when my heart goes to pieces from pain for them [the family in Rakov]. Mother writes in every letter that she wants father to stay there [in New York] and bring her there. Father writes me now that they will not let him stay in the U.S. permanently. When he went to HIAS [Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society] they did not accept his application. Sonika, father should be happy to be there and not in Rakov, because in Rakov the situation is not good.

March 26, 1940

Dear Sonia,

Hayim Yehoshua [Beyle’s brother] has written from Florida—just one letter during this entire time. He writes that we need not worry. They are taking good care of father. He devotes not a single word to our situation, does not ask if we need anything, and God forbid, he does not mention anything at all about whether we could come to America. He writes calmly, as if nothing has ever happened in the world. Nothing has happened to him, because it is quiet over there and they think only about having a good time. I am angry that none of the family we have there is the least bit interested in inviting us to come to them. We know that moving to a new country one does not lick honey, but we think about our children. It would be good to take them out of here once and for all, so they at least could live peacefully during the years of their childhood and youth.

People are leaving here and going to America and to Palestine. Thousands are fleeing from here—refugees and people from Vilna. They get their travel permits by cable—everything is settled very quickly. Naturally we ask why our family, who are people of means, cannot receive us and the family from Rakov? This question has cost me my health.

In fact, nothing was settled quickly nor did many succeed in leaving. Once the war started, international travel became difficult to arrange. Vilna’s travel agents arbitrarily stopped booking tickets for anyone older than eighteen or younger than fifty. Berths on transatlantic ships were scarce due to wartime demand. Even if Doba and Shepseleh had somehow been able to book passage out, it would not have been easy to get in. The U.S. government had not altered its immigration policy after the outbreak of war, but the State Department began enforcing the law more stringently and snarling its red tape more impenetrably. State Department officials justified the squeeze by claiming they were trying to keep out potential spies and saboteurs. But this was a smoke screen for entrenched isolationism, xenophobia, and anti-Semitism. Public opinion was solidly on their side. The majority of Americans had no desire to open the doors to the likes of Doba and Shepseleh. Even after Hitler invaded Poland, the country remained overwhelmingly opposed to easing immigration restrictions. A bill introduced by New York’s senator Robert Wagner to admit twenty thousand German refugee children died in committee in 1939 due to opposition from the powerful anti-immigration bloc and President Roosevelt’s failure to get behind it. The truth is that from September 1939 forward, Vilna’s Jewish residents and refugees had little hope of securing sanctuary in the United States or anywhere else in the world. The ranks of those who succeeded were tiny: according to one report, as of April 1940, a total of 137 Vilna Jews had immigrated to all countries excluding Palestine; of these, 41 were admitted to the United States. The Joint managed to get some into Shanghai or Siberia. South America was a haven for a handful. But very few went from Vilna to America.

Doba blamed the American relatives for refusing to “invite” them (i.e., file the necessary sponsorship affidavits) and there is no evidence that the relatives tried. But even had they done so, it’s unlikely they would have succeeded.

—

“I walk around confused and ponder how everyone could have been envious of me for going to America,” Shalom Tvi wrote to Sonia after the war started. “Maybe in America I could have done something for my children—but then suddenly came such calamity. I have been separated from everyone and only God knows for how long.” The weeks dragged on, he renewed his tourist visa for another three months, letters from Doba and Etl and Beyle trickled in, but otherwise nothing changed. There were no more trips to the museum or the World’s Fair. The sycamores and maples shed their leaves; the sky over the Bronx turned leaden gray. With nothing to do but ask for handouts and worry about his wife and children, Shalom Tvi became despondent. He came to depend more and more on his brother for support and guidance. Abraham found him a job at A. Cohen & Sons packing jewelry into boxes in the shipping room. It was menial, repetitive work but Shalom Tvi was happy to get it—anything to help pass the time. “I go to work a little at my brother’s store and earn a little because I don’t want to stay idle,” he wrote Sonia. “When one does nothing the mood is much worse.”

Shalom Tvi and Abraham had been close in Rakov thirty years earlier. In New York the brothers became close once more. Shalom Tvi was not as strictly observant as his older brother, but they were cut from the same traditional cloth and it was a solace for both of them to be together in old age. Shalom Tvi fell in with his brother’s weekday routine: first thing in the morning they went to shul to pray, then they returned home for a bowl of cereal and two hard-boiled eggs, then Abraham had a short rest on the sofa, and then at ten o’clock they left together for work. The brothers rode home together in the evening chatting in Yiddish in the back of Sam’s car. Shalom Tvi shared a single bathroom with the other family members—eight of them under one roof including Ethel and her husband, Sam Epstein, and their three children, ages twenty-one, eighteen, and twelve.

The Americans called Shalom Tvi the Uncle, and behind his back they joked fondly about his “greenness.” On his first Saturday in America, the Uncle had taken out a piece of paper with an address in Texas written on it and asked one of the nephews to walk there with him. He was incredulous when they told him it was impossible. When a new baby daughter was born, the Uncle made a little sachet with salt inside, tied it with a red ribbon, and tucked it under the cushion of her carriage. Once the Uncle wandered into the living room when one of his pretty young nieces was in the arms of her fiancé engaged in what used to be called heavy petting. “Oh, I see you’re playing cards,” he murmured in Yiddish and left them to it. The younger relatives thought of the Uncle as a benign phantom from the Old World—polite, tidy, quiet, unassuming, wrapped in a cloud of sadness and incomprehensible Yiddish.

What Shalom Tvi thought of the Americans he never said, not even in letters to his wife and daughters. The only one he singled out for special mention was his oldest brother. In America, no one seemed to have much respect for anything or anyone, but all of them respected Abraham. Not only the family, not only the members of the Hebrew Institute of University Heights, not only his fellow Jews. Christian clerics sought him out for his wisdom about the Talmud. The Chevrah Mishnayos—Mishna study class—he founded at the shul was always full of eager students young and old. Though Abraham lived modestly, he was clearly a man of substance—substance grounded in security and law, not like in Poland where every decade a war or pogrom blew all you owned into the whirlwind. A truly religious person, Abraham was tolerant of the beliefs of others and bent to the customs of his adopted country. He let his grandchildren hang a stocking on Christmas Eve and secretly filled it with candy. When one of the granddaughters landed a job that required her to work half a day on Saturdays, Sarah hit the ceiling but Abraham said, “She is an American girl—she’s lucky to have a job—let her work.” Abraham was the patriarch and his word was law, but he laid down the law gently and with humility. “I had two heroes growing up,” said one of his grandsons. “Grandpa and FDR.” Though he had long since given up the work of the scribe, Abraham still loved to make things with his hands; his grandchildren remember him sitting outside in the summer whittling them toys and whistles with their names carved in Hebrew letters. “Mr. Cohen’s patriarchal appearance distinguished him from all the people in the congregation,” wrote one of the members of his shul. “He was the leader of the older generation and lived the way of life which brought respect and admiration even from people unaccustomed to it and unwilling to subscribe to it.”

Shalom Tvi would have been lost in America without his brother. His niece Itel was rich but intimidating. Even her generosity was imperious—at Hanukkah Itel always made a point of giving twice as much gelt (money) to the nieces and nephews as the other aunts and uncles. William was more approachable, but he was so busy with Maiden Form that they rarely saw him. His nephew Sam downstairs was happy to chat and joke in Yiddish, yet most of the time Sam was too consumed by fighting with his brothers over the business to pay his uncle much attention. Shalom Tvi dropped hints about his family. He complained about how much money he had lost as a result of the devaluation of the Polish zloty. The Americans listened, shook their heads, and told him to keep his spirits up. No one talked about the fate of Poland. The name Hitler was a curse that they refused to utter. Abraham sent money; the others were kind but vague.

The visa extension that Shalom Tvi had been granted after the outbreak of war was due to expire on April 13, 1940. As the date approached he sized up his situation. “They will either give me a few more months, or I will have to go back to Rakov,” he wrote Sonia on April 1. “In the meantime I don’t have another place to go. May there be peace! I need papers to go anywhere, and if I don’t have them I will have to go back to Rakov—this is surely not good.” His latest idea—bringing Beyle to America and then traveling with her to Palestine after the war—was dashed when he went to the HIAS office to inquire about the paperwork. The one hope now, Shalom Tvi wrote his youngest daughter, was that “God would bring quiet to the world and we could all come to you together.”

England and France were technically at war with Germany, but Europe had been eerily quiet since the carving up of Poland the previous September. The six-month lull—which came to be known as the phony war—was punctured on April 9, 1940, when the Nazis launched an air and sea attack against Norway and Denmark. Britain and France sent troops to Norway on April 18, but the Allies bungled the defense, and by the end of the month the Germans had pushed them back sufficiently to consolidate a three-hundred-mile line connecting Oslo and Trondheim. Denmark surrendered at once. The swastika now flew over Norway, Denmark, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and half of Poland.

The Cohen family wasn’t paying much attention to the world situation that spring. They had troubles of their own to worry about—business trouble. After weeks of fruitless negotiations over a new contract, Local 65, the CIO-affiliated chapter of the United Wholesale and Warehouse Employees Union, went out on strike against A. Cohen & Sons. Abraham had always considered the warehouse workers at A. Cohen & Sons his friends, practically his family. He took it as a personal betrayal when picketers shouted at him in the street and jostled him as he tried to get inside the new West Twenty-third Street office. Hyman, who had played a reluctant part in the failed negotiations, became irate. It was bad enough that the union guys yelled at his father, but this was the sloppiest picket line he’d ever seen. Hyman had drilled with the First Division in France! He wasn’t going to stand by and watch while these Bolshevik deadbeats slouched around at the entrance to his office. Hyman grabbed a placard from one of the strikers, rested it on his shoulder like a rifle, and, with back straight and chest thrust out, marched a few steps back and forth on the sidewalk—just to show them how it was done. “If you’re going to picket—picket!” he shouted. Everybody laughed and it broke the tension. But it was a bitter day for Abraham.

The workers picketed for three days, after which the mediation board intervened and brought the two parties together. “The strike upset Father,” Hyman wrote later. “He just could not believe that people, friends whom he helped in time of need, would picket against him. Actually they were picketing against the Company. He was badly hurt psychologically and never the same after the strike.”

For Orthodox Jews, the weekend starts at sundown on Friday and ends at sundown on Saturday. Sundays are a workday like any other—which explains why Abraham was at the office when he collapsed on Sunday, April 28. One of the sons heard the old man fall and rushed in to find him conscious but weak. The brothers conferred and quickly decided that their father would be better off at home than in the hospital. They got him into Sam’s car and tried to make him comfortable. Sam, a terrible driver under the best of circumstances, somehow managed to keep the car on the road between Manhattan and the Bronx. When they reached the house, they moved Abraham into a chair and the men carried him up the stairs and got him into bed. Dr. Fred Glucksman, who lived a few doors down on Andrews Avenue, was summoned to do an exam. The doctor broke the news to the family that Abraham had suffered a heart attack. Hyman believed that the warehouse workers’ strike was responsible, but that seems unlikely. Abraham was in his late seventies; the family had a history of high blood pressure and hardening of the arteries; the strike had been settled for some time when he collapsed.

The heart attack had been fairly mild and Dr. Glucksman said that the patient should be okay in a few days if they kept him in bed and made sure he was quiet. But on May 6, a Monday, he took a turn for the worse. By the time Dr. Glucksman arrived at this bedside, Abraham was in a coma. He had suffered a serious stroke. “Pray that he does not recover,” the doctor told the family. “If he does he will be a helpless invalid.”

At dawn on May 10, the Germans terminated the phony war once and for all with a coordinated surprise attack on Luxembourg, Belgium, and the Netherlands—a swift deathblow that was being called a blitzkrieg—lightning war. At eight o’clock that night, Abraham died at his home in the Bronx. Since it was a Friday and after sundown, Shabbat had begun and the body could not be moved. A man from the synagogue came to sit by the bedside of the deceased and pray through the night. The family arranged a funeral service for 1 P.M. on Sunday at the Riverside Memorial Chapel, the same chapel that had handled the funeral of Itel and William’s son, Lewis, a decade earlier, but the leaders of the shul wanted to do something more. They asked to have the pine coffin of the patriarch placed in the sanctuary of the synagogue he had helped to found fifteen years earlier—an honor bestowed only on rabbis and esteemed religious scholars.

University Avenue is a major six-lane thoroughfare slicing north/south through the Bronx, parallel to the East River, but on the day of the funeral the police closed the avenue to traffic on the block of the Hebrew Institute. The synagogue staff set up loudspeakers outside so the crowd that overflowed into the street could hear the prayers. The ancient poetry of the mourner’s kaddish drifted into the soft air of spring.

Yit’gadal v’yit’kadash sh’mei raba

May His great name be exalted and sanctified

Yit’barakh v’yish’tabach v’yit’pa’ar v’yit’romam v’yit’nasei

v’yit’hadar v’yit’aleh v’yit’halal sh’mei d’kud’sha

Blessed, praised, glorified, exalted, extolled, mighty, upraised, and lauded be the Name of the Holy One

B’rikh hu.

Blessed is He.

Abraham’s grandfather had been alive at the time of Chaim the Volozhiner, the beloved student of the Gaon of Vilna. His father, Shimon Dov, had died while the last war raged. Now every hour brought word of fresh disasters from Europe.

Two thousand people turned out that day to pay their respects. It was the end of an era not only for the family but also for Jewish New York. The old guard was passing on and there was no one to take its place. The patriarch had died; there would be no patriarch after him.

While they were sitting shiva, Shalom Tvi approached his nephew Harry. As the oldest son of the oldest son, Harry was now by rights the head of the family. Shalom Tvi took him aside and told him quietly that, because his brother was dead, he must return to Poland. He had found a ship that was due to embark shortly and he was going to buy a ticket. Why should Ethel and Sam Epstein continue to put him up? It was one thing to live with a brother—but a niece and her husband had no obligation.

Ever gracious, Harry sat with the Uncle until he talked him out of it. Ethel and Sam would never throw him out no matter what happened. Europe was burning; the Atlantic was swarming with German submarines; how could he even think of sailing back? Here in the States he had a job and a place to live with people who loved him. He must remain until the war was over and he could be reunited with his own family.

Finally, Shalom Tvi bowed his head and agreed to do as Harry said.

According to family lore, the ship on which he had been planning to sail back to Poland was torpedoed and sunk.

Brussels fell to the Germans on May 17, a week after Abraham’s death. By May 21, German soldiers were on the shores of the channel gazing across toward England. At Dunkirk, what Winston Churchill called the “whole root and core and brain of the British Army” was cut off by the Wehrmacht and had to be evacuated between May 26 and June 3. The Germans entered Paris a week later. The enfeebled French government sued for peace and a French-German armistice was signed on June 22. The Battle of Britain began soon after.

“The big ones make plans which are impossible for our heads to grasp,” Shalom Tvi wrote to Sonia. “God knows how this will end.”

—

July 15, 1940

Dear Sonia,

Soon it will be Rosh Hashanah, but this year the world has turned on its face. A year ago, when I arrived here, my heart was glad. Today there is mourning. Etteh [Beyle’s sister] passed away. Here, my beloved brother Avram Akiva passed away. In New Haven there is also mourning. Hayim Yehoshua, our beloved brother-in-law, has died. Mourning at everybody’s. The air is full of mourning—the pain and the sadness are great.

From your father who kisses all of you,

Shalom Tvi Kaganovich