Chapter 5

Identify Your Clients’ Feelings, Physical Reactions, and Behaviors

In the previous chapter we covered how to structure a session. Did you have a chance to try setting an agenda with a new client or a current client? How did it go? What about reviewing at the end of the session? How did using a structure make a difference to your therapy sessions? I am hoping that you will keep using a structured format. One of the best ways to maintain change is to assign yourself a specific task that reinforces your new behavior. Would you be willing to pick four clients and try setting an agenda and reviewing?

If you did not have a chance to try structuring a session, what got in the way? Did you have negative predictions about structured sessions? Try to set an agenda with just one client this coming week and notice how your client responds.

Set the Agenda

In this chapter we will cover how to identify situations that trigger your client and then how to use the four-factor model to understand your client’s reactions. We will focus on identifying your client’s feelings, physical reactions, and behavior. I want to leave identifying thoughts for the next two chapters.

- Agenda Item #1: Use the four-factor model in therapy.

- Agenda Item #2: Identify your clients’ triggers.

- Agenda Item #3: Understand your clients’ reactions.

- Agenda Item #4: Help your clients identify their feelings.

- Agenda Item #5: Help your clients identify their physical reactions.

- Agenda Item #6: Help your clients identify their behaviors.

- Agenda Item #7: Remain empathic.

Work the Agenda

Clients come to therapy with all kinds of problems. For example, Suzanne is too anxious to talk to the other teachers and make friends, Raoul is procrastinating on his project at work, some clients drink too much, and others feel panic when they try to use an elevator. In this chapter we are going to start using the four-factor model to understand your clients’ problems.

Agenda Item #1: Use the Four-Factor Model in Therapy

Almost every client has specific situations that trigger him, and when triggered he automatically zooms down a well-worn negative path. The path is strewn with a mix of feelings, physical reactions, behaviors, and thoughts and ends in a big negative jumbled black ball. It happens so quickly and automatically that your client never pauses to notice or question his negative path. He is just aware of the big negative ball at the end. The negative path feels like the only option. Take a look at figure 5.1 to see how the negative path works.

Figure 5.1. Your client’s negative path.

Figure 5.1. Your client’s negative path.

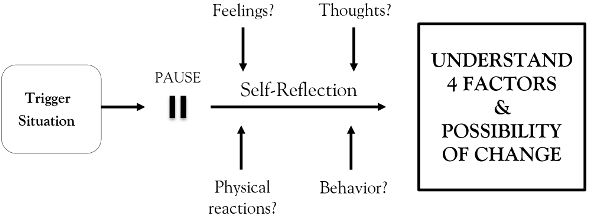

We are going to spend the next three chapters using the four-factor model to help your clients hit the pause button on their negative automatic paths (see figure 5.2). This starts a process of self-reflection, and it is often the first time that a client has fully acknowledged his own thoughts and feelings. As clients become more aware of how the four factors are maintaining their problems, change becomes a possibility.

The first step involves identifying a trigger situation and then identifying and recording your client’s feelings, physical reactions, behaviors, and thoughts. We are going to use the Understand Your Reaction worksheet (which is the same as the first five columns of a thought record) as a tool to identify and record your client’s reactions. You can download a copy at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

| Understand Your Reaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | Feelings

(Rate 1–10) |

Physical Reactions

(Rate 1–10) |

Behaviors | Thoughts |

|

What? Who? Where? When? |

What did I feel? |

How did my body react? |

What did I do? |

What did I think? |

If you are not used to writing during therapy, you may initially find it awkward. However, once you try it, I think you will find writing very useful. For most clients, writing down thoughts and feelings creates a different experience from saying them in their head; writing encourages pausing and reflecting. Using a written worksheet helps organize the session. Plus, your clients can use the Understand Your Reaction worksheet outside of therapy to slow down and identify what is going on when they are upset.

While I think it is important to try a written worksheet, CBT is flexible; identifying the four factors can also be done orally, as part of a therapy dialogue.

Agenda Item #2: Identify Your Clients’ Triggers

Each client has specific types of situations that set his automatic negative path in motion; these are his triggers. To address your client’s problems, you need to know which situations are difficult for him and trigger his negative path.

While many clients are aware of their triggers, other clients have trouble identifying their specific trigger situations. For example, a client may tell you that he is “always” sad, or “always” drinks too much, and can’t identify specific problematic situations. Identifying your client’s triggers helps you start to see patterns and then know what to focus on in therapy.

A helpful first step is to ask your client to monitor his problematic feelings or behaviors and see if there are some situations where his feelings are stronger or his behavior is more extreme. For example, a client of mine, Elsbeth, came to therapy because she was always angry. When I asked for examples of specific situations, she responded that she was angry “all the time.” Her first homework assignment was to monitor her angry feelings and see when they were strongest. She came back having discovered that she was the most angry when her tee nage son didn’t do what she wanted him to do, for example, when he did his homework at 2 a.m., broke curfew, or did not do his chores. She discovered that her anger toward her son was spilling over into the rest of her life.

I often use a simple monitoring worksheet like the one below. You can download a copy of What Is Your Trigger? at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501. I ask my clients to note situations that were the most difficult for them and to rate their feelings from 1 to 10. We often start to see patterns. For example, Suzanne told her therapist that she was very unhappy in her new school “all of the time.” As homework, her therapist asked her to notice situations where she was the most unhappy and rate her moods. Look at how Suzanne filled in the worksheet below. Do you see a pattern?

When Suzanne and her therapist looked at the worksheet, they discovered that she was the most unhappy in social situations with other teachers. None of the situations she identified involved students. Suzanne was surprised. Charting her reactions helped her focus on the situations that were difficult for her, and it also helped her realize that some aspects of school were going fairly well.

Help Your Clients Identify Situations That Are Specific and Concrete

You begin the session with a check-in, set the agenda, and then decide on the agenda item you want to start with. What happens next? You want to identify a specific situation that is problematic for your client and that you can work on in therapy.

Frequently, your client will describe his trigger situation in vague terms, and you don’t really understand what happened. You need to help your client become more specific and concrete. A specific and concrete description includes what happened, with whom, and the specific time and place it occurred. For example, a vague description of a situation would be “My partner doesn’t respect my work”; a more concrete and specific description would be “My partner told me that she thought her work was more important than mine.” Below are some additional examples of situations that are described vaguely, along with more specific and concrete descriptions of the same situations.

The more specific and concrete your client’s description of the situation, the more your client will be emotionally engaged with the situation, and the more he will have access to his feelings and thoughts. Consider your own experience: Think of someone you are a little annoyed with. Now, think of a specific situation when you were annoyed with this person. Try to remember the situation in detail. Chances are that as you thought about a specific situation, you became more annoyed and your feelings and thoughts became more immediate. The same thing will happen when your clients talk about specific situations.

Sometimes your client’s situation is a long, complicated story. In this case, listen to the whole story and then ask what was the worst or most difficult part for your client. It is helpful to identify a situation that lasts from a few seconds to thirty minutes (Greenberger & Padesky, 2016)—any longer and your client will probably have a large variety of feelings and thoughts, and it will be hard to focus on the main ones.

Questions to help identify a specific situation. I know I have a clear understanding of the situation if I can form a picture in my mind. If not, I ask my client the W questions: What happened? Who was involved? Where did it happen? and When did it happen? I am looking for the facts of the situation. In some ways it is similar to being a detective or a newspaper reporter on a fact-finding mission, except rather than being a solo operator, you are a fact-finding team with your client. I usually start with being sure I understand What happened.

Let’s look at an example. One of my clients was upset with her boyfriend. I asked for an example. She responded, “My boyfriend was really mean to me last night.” Let’s see if we have the answers to the W questions. Do we know What happened? No, we don’t. Do we know Who was involved? Yes, the boyfriend, but we don’t know if anyone else was involved. Do we know Where it happened? No, we don’t. Do we know When it happened? Yes, it happened last night. Before we can start to explore my client’s feelings, physical reactions, behaviors, and thoughts, we need a clearer idea of what occurred.

Here is another example. If you remember from chapter 4, Suzanne’s main agenda item was about being invited to a barbecue at the principal’s house. She doesn’t feel like going and thinks she will just say no. Her therapist wants to get a better understanding of the situation. Let’s look at what happens when her therapist uses the four W questions.

Suzanne: I was invited to a barbecue event at the principal’s house.

Therapist: I want to make sure that I understand. (Notice her therapist explains what she will do.) What is the event?

Suzanne: The principal invited all the new teachers to her home for a barbecue.

Her therapist doesn’t want to fire a volley of questions at Suzanne, but she also wants more information. You can ask more than one of the W questions at the same time.

Therapist: Can you give me a better sense of what’s involved with the barbecue, for example, who was invited, where is it happening, and when?

Suzanne’s therapist learns that Suzanne was invited to a barbecue at her principal’s house along with the three other new teachers. It is taking place after school in two weeks. Once you are clear on the situation, you and your client can start to figure out why she is upset by using the four-factor model.

Your Turn! Help Neale Identify a Specific Situation

Neale, a thirty-six-year-old man, starts a session by saying he wants to focus on his relationship with his mother. Try to help him specify a situation that he wants to work on.

- Therapist: You said you wanted to focus on your relationship with your mother today.

- Neale: Everything is going wrong; my relationship with my mother is worse than ever.

Look at the three possible responses below and pick the one that will help you get a better understanding of the situation that is troubling Neale.

- Can you tell me more about your relationship with your mother?

- I can see that your relationship with your mother is really upsetting you; it feels as if everything is going wrong.

- Could you give me an example of what is going wrong between your mother and you?

Response #3 is the most likely to help the client identify a specific situation. Response #1 is too vague. If this was the first time you were hearing about Neale’s difficulties with his mother, it could be a good question, but it does not help you focus on a specific difficult situation. Response #2 is supportive, but it also does not help identify a difficult situation.

- Therapist: Could you give me an example of what is going wrong between your mother and you?

- Neale: We had a big family dinner on Sunday afternoon and it was just awful. My mother and I just don’t get along.

Before looking at the therapist’s response, ask yourself what the therapist could ask to help Neale be more specific about what happened.

- Therapist: You were saying that the family dinner was just awful last Sunday. Can you tell me what happened?

- Neale: I am so upset because my mother was so critical of me.

Ask yourself the W questions: Do you know What happened? Who was involved? Where it happened? When it happened? You don’t know what happened; you know Neale’s mother was involved and that the situation occurred at a family dinner last Sunday. We need more information.

Look at the three possible responses below and pick the one that will help you get a better understanding of the situation.

- When you say your mother was critical of you, can you help me understand what your mother did?

- Can you tell me more about your mother being critical?

- When your mother was critical, what did you think?

- Response #1 is most likely to help Neale become more specific about the situation. Response #2 is a good start, but it is too vague. Neale could react by talking about his feelings or thoughts, or about the situation. In response #3 you don’t know what the client means by critical, so it is too early to ask about his thoughts.

The Facts About a Situation Are Different from the Meaning of a Situation

Clients frequently include their thoughts or interpretation of what the situation meant when describing the situation. When you start to separate the facts about the situation from the thoughts and feelings about the situation, you and your client begin to get a more objective idea of what occurred. Let’s look at an example. A client identifies the following situation: “My wife doesn’t care about my mother; she told my mother we were too busy to visit her.” The facts of the situation are that his wife told his mother that they were too busy to visit; the client’s thoughts or interpretation of the situation are, “My wife doesn’t care about my mother.” Let’s look at another example. A client says, “My new girlfriend asked me home to meet her parents. She’s moving too fast; I don’t want to get serious.” In this example, the facts of the situation are the girlfriend invited the client home to meet her parents; the thoughts or what the situation meant to the client are, “She is moving too fast; I don’t want to get serious.”

Often a client will use an adjective to describe the other person in the situation; the adjective is usually the client’s thought about the other person. For example, a client says, “My child was very inconsiderate toward the teacher.” “Inconsiderate” is an adjective. You know that the client thought the child was inconsiderate, but you don’t know what the child did. If you want to understand the facts of the situation, it is helpful to ask, “What did your child do that made you think he was inconsiderate?”

Sometimes a client will include his feelings as part of the situation; for example, when describing a situation he will say, “I was so angry at my mother when she was late.” The fact is that his mother was late; the feeling is anger. A client can also include his behavior in the description of the situation, for example, “When my boss yelled at another coworker, I just sat there and did nothing.” The boss yelling at another coworker is the fact in the situation; the client doing nothing is the client’s behavior.

Your Turn! Separate the Facts about the Situation from the Thoughts about the Situation

Below are examples of situations where clients mixed up the facts about the situation and their thoughts about the situation. In the examples below, separate the facts about the situation from the client’s thoughts. Complete the worksheet below before looking at my answers in the appendix.

| Examples of Situations | Facts about the Situation | Client’s Thoughts about the Situation |

|---|---|---|

|

Instead of doing homework, I was lazy and went out with friends. |

||

|

My boss told me I did a good job, but he didn’t really mean it. |

||

|

My child is not normal; he is not crawling at age five months. |

||

|

The huge mess my husband left in the kitchen |

Agenda Item #3: Understand Your Clients’ Reactions

Identifying trigger situations is an important first step. The next step is using the four-factor model to understand your client’s reaction. It is important to explain what you will be doing, both so that your client understands the process and so that he learns a tool to use outside of therapy. I use the Understand Your Reaction worksheet that we looked at in the beginning of the chapter as a structure. I show the worksheet to my client and explain each column. I usually say:

I think you did a really good job identifying the situation. What I would like to do now is to see if we can understand your reaction by identifying your feelings, physical reactions, behaviors, and thoughts—and then see how they all go together. I call this using the four-factor model.

I want to complete this worksheet. (I get out the worksheet or draw one on a sheet of paper.) You see there are five columns. This first column says “Situation,” and we are going to write down the situation we just identified. (I write it down or the client writes it down.) We are then going to see if we can identify your feelings, physical reactions, behaviors, and thoughts and write them down in the next columns.

When clients see the five columns, they automatically become more organized, and some of the jumble and distress starts to diminish. My own attitude is one of engaged curiosity, as this models a helpful attitude my client can take toward his own problems. Notice how I start by saying, “I think you did a really good job identifying the situation.” Providing positive feedback for learning a specific skill reinforces the skill and helps the therapy relationship. Many of our clients rarely receive any positive feedback; to hear that they did something well is important.

YOUR TURN! Practice in Your Imagination: Explain the Understand Your Reaction Worksheet

Choose a client who you think would benefit from identifying his or her feelings, physical reactions, behaviors, and thoughts. Before you start, rate from 1 to 10 how comfortable you feel introducing and using the Understand Your Reaction worksheet. At the end of the exercise, rate your level of comfort again to see if it changed. Now, let’s try this exercise.

Imagine you want to introduce the Understand Your Reaction worksheet to your client. Try to get a picture of him or her in your mind. Imagine yourself in your office with your client. See your office; notice the sounds and smells in the room. Read over how I suggest introducing the worksheet while imagining yourself saying the words. You can also use your own phrases. Really hear and feel yourself taking out the worksheet and explaining it to your client. Now, imagine explaining the worksheet two more times with the same client. Each time, imagine that your client responds positively.

Agenda Item #4: Help Your Clients Identify Their Feelings

In this book, we are going to start with identifying feelings, then physical reactions and behavior, and lastly thoughts. This is because most clients are more aware of their feelings than their thoughts and tend to come in talking about feelings. However, in practice, you could start with any of the four factors. I often start with the factor that my client brings up first.

The ability to label feelings is a part of affect regulation, or managing one’s feelings in a healthy way. When you ask your client, “What were you feeling?” you are asking him to pause and reflect, which automatically interrupts his negative path. Labeling feelings helps both client and therapist understand the client’s reactions. Asking your client to label his feelings gives the message that you are interested in his experience. Clients’ feelings can also guide therapy. You may want to try different interventions depending on your client’s dominant feelings. For example, if your client tells you he feels “bad,” it is hard to know where to start, but if he tells you he feels “anxious,” you can start to explore his fears.

What Are Feelings?

Let’s see if we can understand Suzanne’s feelings about going to the principal’s barbecue. When Suzanne’s therapist asked her what she was feeling, Suzanne answered, “I just don’t want to go.” Let’s stop for a moment. Suzanne’s response is not a feeling, it is a thought about the behavior Suzanne wants—or in this case, doesn’t want—to do (she does not want to go to the barbecue).

If Suzanne’s response was not a feeling, then what is a feeling? As I mentioned earlier, feelings are usually one word. There are generally six main emotions that clients identify: happy, mad, sad, anxious, guilty, and ashamed. While there are many other feelings, these are the basic ones. Take a moment to look at the Identify Your Feelings handout, which is a more comprehensive list of feelings; you can download it at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501. Reading over this handout will help expand your own vocabulary. Clients find it helpful when you find a word that exactly captures what they are feeling.

Strategies to Identify Your Client’s Feelings

While some clients can give very accurate and detailed descriptions of what they are feeling, others have difficulty. Remember my client Elsbeth, from earlier in the chapter, who was angry with her son for not doing his homework or his chores? Initially she was only aware of her anger, but when we started paying attention to her feelings, she discovered that she was more anxious than angry.

If your client has trouble identifying his feelings, here are some interventions you can try:

- Show your client the Identify Your Feelings handout and ask if one of these feelings seems to fit.

- Ask your client to notice his feelings during the coming week, and see if he can start to identify his feelings. Often just paying attention to feelings can be helpful. Some clients have never asked themselves the question, What am I feeling?

- Ask your client to notice when he becomes physically tense and to try and label his feelings at that moment.

- You can discuss feelings with your client and how to know whether someone is happy, sad, mad, glad, anxious, guilty, or ashamed. Ask your client to identify physical symptoms, behaviors, and thoughts that go with each feeling.

Raoul generally found it hard to identify his feelings. In one of his therapy sessions, he came in looking very agitated and said he was really upset about his boss’s comment at a meeting. His boss had said that Raoul’s project seemed to be going slowly, and he hoped Raoul would be able to meet the deadline. When the therapist asked Raoul if he could describe his feelings a little more, Raoul shrugged, looked down at the floor, and said he felt “awful.” His therapist thought it would be helpful if Raoul could start to be more aware of his feelings. She tried three interventions. First, they talked about feelings and how you could know what you are feeling. Second, his therapist gave him the Identify Your Feelings handout and discussed it with him. Third, for homework his therapist asked him to record three situations when he felt awful, to note what was happening in his body, and to look at the Identify Your Feelings handout and try to label his feelings. When Raoul came back the next week, he had completed his homework and was able to identify that he felt nervous and angry. This helped him and his therapist start to address these feelings more specifically. His therapist also started directly asking whether he was nervous or angry when he said he was feeling “awful” or “upset.”

One of the difficulties in identifying feelings is that we often use “feel” when we are making a judgment and are really describing what we “think.” For example, you might say, “I feel that the movie was too slow” when what you really mean is “I think the movie was too slow.” It is even more difficult to differentiate thoughts and feelings in statements like “I feel stupid” or “I feel incompetent.” Even though these statements start with “I feel,” they are really judgmental thoughts about ourselves. We say, “I feel stupid” when we mean, “I think I am stupid.” Thoughts are so closely connected to feelings that it can be hard at first to see the difference, but the more you use the four-factor model, the easier it will get.

Now, let’s go back to Suzanne and see how her therapist helps her identify her feelings about the invitation to the principal’s barbecue.

Therapist: I hear you don’t want to go, but I am wondering what your feelings are when you think of the invitation.

Suzanne: What do you mean? I just don’t want to go.

Often when you ask clients what they were feeling, they answer with a feeling word. However, Suzanne repeated her initial response. Her therapist thought that Suzanne needed more guidance.

Therapist: Well, feelings are usually expressed in one word. While there are many feelings, it would be helpful to ask yourself whether you were feeling happy, mad, sad, anxious, guilty, ashamed, or any other feeling.

Suzanne: Oh that’s easy, I was really nervous and worried, and I think also embarrassed.

Giving Suzanne the basic list of feelings helped her start to identify her own feelings.

Help Your Clients Rate Their Feelings

In CBT, we often ask our clients to rate the intensity of their feelings. At first it can feel strange to ask your client to rate his feelings; however, it is very helpful. You are asking your client to reflect on his feelings rather than automatically respond to them. Here is an example of how rating his feelings helped one of my clients. He was a man in his late forties who had intense anxiety attacks at work and would subsequently become immobilized for the whole day. A few weeks after we had started working together, he came in smiling and said, “I had one of my anxiety attacks at work last week, but I rated my anxiety, and I realized it was only a 7. So I kept on working and it went away.” Rating his feelings helped my client get a different perspective on his feelings.

I usually ask clients to first identify and label their feelings and then to rate their feelings. I say,

You did a good job identifying your feelings. (Notice I am reinforcing my client for a specific task.) Before we move on, I would like to ask you to look at each feeling you identified and rate how strongly you had this feeling from 1 to 10. Ten would be the strongest you have ever felt this feeling and 1 would be not having the feeling at all. Rating your feelings can help us get a better understanding of how you are feeling. Would you be willing to try?

YOUR TURN! Help Suzanne Rate Her Feelings

Let’s go back to the situation where Suzanne was invited to the principal’s barbecue. Imagine that Suzanne has just identified her feelings. You now want to help Suzanne rate the intensity of her feelings.

- Therapist: When you received the invitation to the barbecue, what were your feelings?

- Suzanne: Oh that’s easy, I was really nervous and worried, and I think also embarrassed.

- Therapist: You just did a really good job of identifying your feelings. (Note how the therapist is giving specific feedback on a task.)

Look at the three possible responses below and pick the one that will help Suzanne rate her feelings.

- Can you tell me what you are nervous about?

- I think it would be helpful if you could look at each feeling and rate how strongly you felt, from 1 to 10. Ten is the strongest you have ever felt this feeling, and 1 is not at all. Would you be willing to try?

- Lots of people are nervous when they are invited to a party. It’s a very normal reaction.

Response #2 is the most likely to help Suzanne rate her feelings. It clearly explains what the therapist would like her to do. Response #1 starts to explore the thoughts that go with the feeling of being nervous. It is too early in therapy to identify thoughts, as you have not finished identifying and rating feelings. Response #3 is a supportive comment, but it does not help Suzanne rate her feelings.

- Therapist: I think it would be helpful if you could look at each feeling and rate how strongly you feel it, from 1 to 10. Ten is the strongest you have ever felt this feeling, and 1 is not at all. Would you be willing to try?

- Suzanne: Well sure. Where do I start?

Look at the three possible responses below and pick the one you think will help Suzanne start to rate her feelings.

- Where would you like to start?

- I can tell you really want to get better, which is very important. Learning about our feelings is a key part to getting better.

- Why don’t we start with the first feeling you listed, which was “nervous.” When you think of the invitation, 1 to 10, how nervous are you?

Suzanne is asking for guidance on how to rate her feelings. Response #3 is the most likely to help Suzanne start to rate her feelings. It clearly explains what the therapist would like Suzanne to do. Responses #1 and #2 don’t address Suzanne’s question, “Where do I start?”

Suzanne and her therapist rate all of her feelings. Before filling in the Understand Your Reaction worksheet, her therapist says, “You did a good job of rating your feelings. Just to summarize, you were nervous at a 7, and worried at an 8, and embarrassed at a 6. Is that right? Can we write it down?” Notice that the therapist makes a summary statement and then explains that she wants to fill in the worksheet. This keeps therapy organized. Below is how Suzanne recorded her responses on the Understand Your Reaction worksheet.

| Understand Your Reaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | Feelings

(Rate 1–10) |

Physical Reactions

(Rate 1–10) |

Behaviors | Thoughts |

|

What? Who? Where? When? |

What did I feel? |

How did my body react? |

What did I do? |

What did I think? |

|

Principal invited me to barbecue with the other new teachers |

Nervous (7) Worried (8) Embarrassed (6) |

|||

Agenda Item #5: Help Your Clients Identify Their Physical Reactions

Physical reactions are often clues to our feelings. Plus, a client can misinterpret his physical symptoms, leading to emotional distress or dysfunctional behaviors. For example, a client may assume that if his heart is pounding he is having a heart attack or it is dangerous for his health. He becomes very anxious and starts to avoid situations where his heart pounds. In reality, his pounding heart is related to too much coffee or another issue and is not dangerous. Unless your client is able to identify his physical reactions, you can’t explore what these physical reactions mean to him.

While some clients are very aware of their physical reactions, other clients are unaware. The easiest way to identify your client’s physical reactions is to simply ask, “How did your body react?” or, “What were you feeling in your body?”

If you are working with a client who has difficulty identifying his feelings, it can be helpful to start with identifying his physical reactions, and then move on to identifying feelings. Often specific physical reactions go with specific feelings. For example, Raoul discovered that when he felt angry he was hot, when he felt anxious he was shaky, and when he felt sad he had a lump in his throat. As he learned to relate his physical symptoms to his feelings, it became easier for Raoul to identify his feelings. When your client identifies his physical reactions, it encourages self-reflection and helps him hit the pause button and stop zooming down the path of his automatic negative reaction.

Suzanne’s therapist asked her to identify the physical reactions that went with her feelings about being invited to the barbecue. Suzanne indicated that she got a clenched stomach and felt tense in her shoulders. She rated her clenched stomach at about a 4 and her tense shoulders at about a 5. She was surprised at how low her ratings were. Often when my clients rate their physical reactions, they realize that they are not as strong as they had thought. If, on the other hand, the physical reactions are very strong, this suggests you may want to teach your client specific skills to manage his physical symptoms.

This coming week, try to notice any increase in your own physical tension. Ask yourself what you were feeling and what you were thinking. See if you learn anything.

Agenda Item #6: Help Your Clients Identify Their Behavior

Next you want to identify your client’s behavior. I usually simply ask, “What did you do?” I am looking for behaviors that indicate that my client is avoiding a situation, acting impulsively, or behaving in a way that is likely to make the situation worse. For some clients, when you slow down and help them specify what they did, it is a first step in acknowledging their problematic behavior and taking responsibility for their actions. A client of mine, Connor, had difficulty controlling his anger and tended to minimize his angry outbursts. He was describing how angry he was at his friend for not repaying a minor debt. He initially described his behavior as “letting off some steam.” When I asked what he had done, he sheepishly told me that he kicked a door so hard that he smashed the glass insert. Connor went on to blame his friend for not paying the debt and making him so angry that he kicked the door. When we looked at his behavior, Connor could see that his friend had not “made” him kick the door, and that kicking a door so hard that he broke the glass insert was not just “letting off steam.”

To really understand your client’s behavior, you want a description of his behavior that is specific and concrete, like Connor’s. This way, you can examine the consequences of the behavior and the appropriateness of the response. Clients often initially use a vague descriptor, such as “I just gave up” or “I freaked out.” It is important to ask what your client actually did.

Here are some examples of vague descriptions of behavior and specific descriptions of the same behavior. You want to know what your client did, whom he did the behavior with or to, where he was, and when it happened.

| Examples of Vague and Specific Behaviors | ||

|---|---|---|

| Situation | Vague Behavior | Specific Behavior |

|

My father told me I should not have dropped out of school. |

I withdrew. |

I sat at the dining room table completely silent for the rest of the meal. |

|

My husband came home so drunk he could barely stand. |

I got angry. |

I stood in the kitchen and yelled at my husband that I was tired of him drinking all the time. |

|

My boss at the restaurant told me I had made a mistake on two customers’ orders, and he wanted me to double-check all orders. |

I did what my boss asked. |

I returned to serving tables and double-checked the orders. |

I often ask my clients about the consequences of their behaviors. This is a question many of my clients have never asked themselves. It is important to look at both short-term and long-term consequences. Often, avoiding dealing with a situation or having angry outbursts has relatively positive short-term consequences but very negative long-term consequences, which many clients have never considered.

Let’s return to Suzanne’s invitation. Her therapist wants to identify her behavior and asks Suzanne how she had responded to the invitation. Suzanne said, “I just got it three days ago and I’m not sure what to do.”

Ask yourself if you know what her behavior is. You don’t really know. It seems that her behavior is that she has not responded to the invitation, but you need to check. Given that it has been three days, I would guess that Suzanne is avoiding dealing with the invitation. Is her statement “I’m not sure what to do” a behavior, feeling, physical reaction, or thought? (Try to answer before reading on.) It is a thought. At this point I would notice the thought but not comment on it, as we are concentrating on her behavior. Remember, you want to stay organized. I put that thought in my back pocket, so when I ask Suzanne to identify her thoughts, if she does not mention “I’m not sure what to do,” I have it in reserve and can take it out at the right moment.

Below is a summary of what we know about Suzanne’s reaction to the invitation from the principal. We don’t yet know Suzanne’s thoughts, but we will cover that in the next chapter.

| Understand Your Reaction | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | Feelings

(Rate 1–10) |

Physical Reactions

(Rate 1–10) |

Behaviors | Thoughts |

|

What? Who? Where? When? |

What did I feel? |

How did my body react? |

What did I do? |

What did I think? |

|

Principal invited me to barbecue with the other new teachers |

Nervous (7) Worried (8) Embarrassed (6) |

Clenched stomach (4) Tense shoulders (5) |

Has not responded |

|

Agenda Item #7: Remain Empathic

Although CBT is structured, it is not rigid, and the therapeutic relationship is critically important. Using summary statements and asking open questions are key counseling skills for maintaining an empathic relationship while adhering to the structure of CBT.

Summary statements help your clients pause and reflect on what they just said. A good summary statement can be very simple. It’s as if you are holding up a mirror that helps your clients look at themselves. When you summarize, you also let your clients know that you heard them. Let’s try one. Your client starts a session saying, “I am not sure which situation I want to focus on. First, the whole party was a disaster. My three-year-old child screamed and cried most of the night; at the end of the evening, my husband told me he never wants to have another party. Second, work has been awful this week, once again my boss ignored my comments at a meeting; and third, to top it all off, my husband got really drunk again.” How could you summarize what your client just said? One way is to simply say, “It is hard to know what to focus on, since so much happened. Should we talk about the party, what’s been happening at work with your boss ignoring your comments, or your husband getting drunk again?” The summary helps your client pause and think about where she would like to start.

Earlier we talked about open and closed questions. If you remember, closed questions can be answered with either a single word or a short phrase. Examples of closed questions are “Did you ask your boss for a year-end evaluation?” and “Did you use cocaine over the weekend?” Closed questions can usually be answered with a yes or no, or with facts. Open questions ask people to think and talk about their thoughts and feelings. Examples of open questions are “How did you feel after you asked your boss for a raise?” and “When your friend offered you cocaine, what were your thoughts?” As you use the four-factor model as a structure to explore your client’s reactions, remember to use summary statements and open questions.

Homework: Practice CBT

Before continuing with the next chapter, take some time to try the homework.

Apply What You Learned to a Clinical Example

Complete the following exercises.

- Exercise 5.1: Raoul’s Boss Is Difficult

- Exercise 5.2: Find the Facts

- Exercise 5.3: Mary Treats Her Son Badly

Apply What You Learned to Your Own Life

After you have completed the homework assignments below, pause and take a moment to think about what you learned about yourself. Then, think about the implications of your experience with these exercises for your therapy with clients.

Homework Assignment #1 Describe a Specific and Concrete Situation

Think of a situation in your own life where you would describe someone in a general, vague manner, such as, “My partner is self-centered,” “My boss is unreasonable,” or “My father is very frail.” Now try to make the situation more concrete and specific. Think of a specific example and ask yourself, What happened? Who was in the situation? Where did it happen? and When did it happen?

What did you learn from specifying the situation? Did it make a difference?

Homework Assignment #2 Describe a Specific and Concrete Behavior

Think of a behavior that you either like or dislike about yourself and that is a vague description. For example, are you messy, kind, organized, thoughtful, ambitious, easygoing, or easily distracted? Now try to think of a specific example of this behavior and describe your behavior in a more specific and concrete manner. What was the impact of giving a specific description of your behavior?

Homework Assignment #3 Rate Your Own Feelings

Often my students are skeptical about the benefit of rating feelings until they try it for themselves. This coming week, pick three different situations. At least one should be a situation that upset you. Try to first identify your feelings. You may have only one feeling, but you may have many. Remember: if you have trouble identifying your feelings, ask yourself if you felt happy, mad, sad, anxious, guilty, or ashamed. You may also have lots of other feelings. Once you have identified your feelings, rate each one. Complete the chart below. Did rating your feelings make a difference? What did you learn?

| Identify Three Situations | Identify Your Feelings in Each Situation and Rate Each Feeling from 1–10 (1 = not at all, 10 = the strongest you have ever had this feeling) |

|---|---|

Apply What You Learned to Your Therapy Practice

It is now time to start using the Understand Your Reaction worksheet. Don’t worry if it feels awkward at first; it is important to try.

Homework Assignment #4 Use the Understand Your Reaction Worksheet with a Client

Choose a current client you think would benefit from and like using the Understand Your Reaction worksheet. Then complete the steps below.

Step 1: Ask your client to identify a specific situation that he wants to work on. Be sure to ask What happened? Who was involved? Where did it happen? and When did it happen?

Step 2: Explain that you want to understand the situation using the four-factor model, and show your client the Understand Your Reaction worksheet.

Step 3: Ask about your client’s feelings and have your client rate their intensity from 1 to 10.

Step 4: Ask about your client’s physical reactions and have your client rate their intensity from 1 to 10.

Step 5: Ask about your client’s behavior.

Complete the worksheet with your client. If it is the first time you are trying to use the four-factor model with a client, you may feel awkward, and it may not go smoothly. But that’s okay! Think of the first time you rode a bike, drove a car, tried to swim, or cooked a turkey. If you are like most people, you were unsure how to do it. The more you practiced, the better you got. Think of me cheering you on. Remember that the goal of homework is not to do it well, but to try.

Let’s Review

Answer the questions under the agenda items.

Agenda Item #1: Use the four-factor model in therapy.

- How can you use the four-factor model in therapy?

Agenda Item #2: Identify your clients’ triggers.

- What are four questions you could use to specify your client’s trigger situation?

Agenda Item #3: Understand your clients’ reactions.

- How could you introduce using the four factors to understand your client’s reaction?

Agenda Item #4: Help your clients identify their feelings.

- How could you explain a feeling?

- Is “I feel like a failure” a feeling or a thought?

Agenda Item #5: Help your clients identify their physical reactions.

- What is a good question to identify your clients’ physical reactions?

Agenda Item#6: Help your clients identify their behaviors.

- Your client says, “I want to punch him in the face.” Is this a behavior? If not, is it a feeling, physical reaction, or thought?

Agenda Item #7: Remain empathic.

- What is the purpose of summarizing your client’s response?

Figure 5.2. Your client hits the pause button.

Figure 5.2. Your client hits the pause button.