Chapter 8

Look for Evidence and Create Balanced Thoughts

In chapter 7 we covered how to help your clients identify their thoughts. Did you have a chance to notice your own thoughts? Did you ask your clients about their thoughts and feelings? What did you discover?

If you did not do the homework, think about an upsetting experience that happened last week. Try to identify your feelings and thoughts. What did the situation mean to you? What was your worst-case scenario? Did you have any images?

Set the Agenda

In this chapter we are going to build on the Understand Your Reaction worksheet and learn how to work with thought records. You will ask your clients to examine the evidence for their negative thoughts and develop a balanced thought that takes into consideration all of the evidence. The whole process is called cognitive restructuring.

- Agenda Item #1: What are thought records?

- Agenda Item #2: Explain looking for evidence.

- Agenda Item #3: Find evidence that supports negative thoughts.

- Agenda Item #4: Find evidence against negative thoughts.

- Agenda Item #5: Develop balanced thoughts.

Work the Agenda

In chapter 5 we talked about how your client has a well-worn automatic negative path that she zooms down, ending up in a big black jumbled ball of feelings, physical reactions, behaviors, and thoughts. One way to hit the pause button on your client’s automatic negative reaction is to use the four-factor model to help your client understand her reaction. Once your client has identified her feelings, physical reactions, behaviors, and thoughts, she is ready to actively change her negative path. One way to help your client change her negative path is to ask her to step back and examine the evidence for her thoughts. Negative thoughts are like thinking habits; we assume they are true and don’t stop to question whether they make sense. However, habits can be changed. Looking for evidence starts a process of developing new and more positive thought habits that are based on reality.

Agenda Item #1: What Are Thought Records?

A thought record is essentially a structure for helping your client look for the evidence for her hot thoughts. In its simplest form, a thought record is a worksheet where a client identifies a problematic situation and then records her feelings and thoughts about the situation. The client then choses one thought to focus on. For a thought record to be effective, the thought the client chooses needs to be a hot thought. Once your client has identified the hot thought she wants to explore, she then looks for the evidence for and against her thought. After the client has examined the evidence, she develops a new more balanced or alternative thought. Many thought records also include space to record physical reactions and behavior. The Understand Your Reaction worksheet can be used as the first five columns of a thought record. Thought records also frequently involve having clients rate how much they believe their new balanced thought and rerate their feelings after completing the thought record; however, this is not essential. Below are the steps to complete a thought record. The steps in italics are common but not essential to the process.

- Identify a problematic situation.

- Identify and rate feelings.

- Identify physical reactions.

- Identify behaviors.

- Identify thoughts.

- Choose a hot thought (a thought that is related to a negative feeling and a negative evaluation of self, other, or the future).

- Look for evidence for and against the hot thought.

- Create a balanced or alternative thought based on all of the evidence.

- Rate the extent to which you believe the new balanced thought.

- Rate your feelings now that you have examined the evidence.

I use the Examine the Reality of Your Thoughts worksheet, which follows, to help clients complete the rest of the thought record process.

| Examine the Reality of Your Thoughts | |

|---|---|

| Thought I want to examine: | |

| Evidence for My Thought | Evidence Against My Thought |

| Conclusion or thoughts that consider all the evidence: | |

The theory behind thought records is that clients assume their negative thoughts are true. Asking clients to examine the evidence for their thoughts stops their automatic reaction and starts a process of self-reflection. When clients examine the evidence for their thoughts and create their own balanced thought, they develop new ways of thinking and less extreme attitudes toward the world and themselves. New ways of thinking open up the possibility of behavioral change. Evidence clearly shows that this process of cognitive restructuring is related to alleviating depression and anxiety (Beck & Dozois, 2011).

A written thought record is not essential. Looking for the evidence for a thought can be done as part of a therapy conversation. However, I would encourage you to use the Understand Your Reaction and Examine the Reality of Your Thoughts worksheets as written tools. A written thought record provides a structure and makes the process of identifying thoughts and looking for evidence very concrete. Some therapists like to use a seven-column thought record with space for identifying the four factors, looking for evidence, and developing a balanced thought. Dennis Greenberger and Christine Padesky use this type of thought record in their book Mind Over Mood (2016). Personally, however, I like to break the thought record down into two stages, first using the Understand Your Reaction worksheet and then the Examine the Reality of Your Thoughts worksheet. You can download both at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

Although looking for evidence is a powerful intervention, looking for evidence once will not shift a longstanding negative thought. Your clients will need to complete many thought records, over a period of time, to change their negative thoughts. However, while a client’s thoughts vary somewhat from situation to situation, most clients have recurring negative thinking patterns. If you identify a client’s thoughts in one situation, most likely these thoughts will recur in other situations. This means that the thought record you complete for one situation will often be relevant to other situations.

Choose a Hot Thought

If your client has one central negative hot thought that is closely related to her emotional distress, that is the thought you will focus on. However, your client may have more than one hot thought, for example, I am an inadequate mother and My partner does not love me. In this case, your client needs to choose which thought to work with, as you can only examine the evidence for one thought at a time. If a client has more than one hot thought, I ask, “Which thought do you think is the most central, or the most important for us to examine?” Another question I have found helpful is, “Which thought do you think is most closely related to your strongest negative emotion?” Clients usually know which thought they need to focus on. Most of our negative thoughts are repetitive. If your client chooses to examine I am an inadequate mother, she will have another chance to examine My partner does not love me.

What Is Socratic Questioning?

All CBT books talk about the importance of Socratic questioning. The term comes from the Greek philosopher, Socrates. Socratic questioning is the idea that skillful questioning can help your clients examine the assumptions behind their thoughts, consider aspects of the situation they had ignored, or understand their situation from a different perspective. Your role is to ask questions that help your client understand her problems in a new light.

The basic idea is that it is more effective to ask questions that help clients reach their own conclusions than to tell a client what to think. If I could post one sticky note on all my readers’ heads, it would say:

Agenda Item #2: Explain Looking for Evidence

Once your client has identified a hot thought, you need to explain the idea of looking for evidence. Essentially, you are going to teach your client to examine her thoughts for their validity rather than treating thoughts as facts. Your client needs to learn to take a step back and put some distance between herself and her thoughts.

My clients almost always immediately grasp the idea of looking for evidence, though sometimes they assure me that they know their negative thoughts are accurate. Here is how I usually explain looking for evidence (you can find a copy at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501):

You did a really good job of identifying your thoughts and catching the negative thoughts that cause you to feel bad. I am wondering if you would be willing to examine your thoughts. I would like to look at the evidence that supports your negative thoughts, and also at evidence that doesn’t support your negative thoughts. Negative thoughts are like thought habits. By that I mean they are ways of thinking that you are used to, but you have not examined whether they are accurate. When we look for evidence, I want us to focus on facts. That way, we can evaluate the accuracy of your thoughts. Would that be okay with you?

We need to pick one thought that we want to examine. I want to look over the thoughts you identified that go with your negative feelings and see if we can pick one that feels the most central to you, or is the most related to your strongest negative emotional reaction.

YOUR TURN! Practice in Your Imagination: Explain Looking for Evidence

I want to ask you to imagine explaining looking for the evidence for a hot thought. Before you start, rate from 1 to 10 how comfortable you feel explaining looking for evidence for and against a hot thought. At the end of the exercise, rate your level of comfort again to see if it changed. Now, let’s try this exercise.

Choose a client who you think would benefit from looking for evidence for his or her thoughts. Try to get a picture of him or her in your mind. Imagine yourself in your office with your client. See your office; notice the sounds and smells in the room. Imagine that your client has identified a negative thought and you want to explain how to examine the evidence for his thought. Read over how I suggest explaining the process of looking for evidence while imagining yourself saying the words. You can also use your own phrases. Really hear and feel yourself explaining how to examine the evidence. Now, imagine explaining looking for evidence two more times with the same client. Each time, imagine that your client responds positively.

Agenda Item #3: Find Evidence That Supports Negative Thoughts

If you are going to help your client reevaluate her negative thoughts, you need to understand the evidence she uses to support them. Many clients find that writing down the evidence, or saying the evidence out loud, makes it more manageable. It becomes a fact that you can talk about, rather than something that sits in your head. Sometimes when a client starts to look for facts that support her negative thoughts, she realizes that there aren’t any, or not as many as she thought. Sometimes a client discovers that her negative thoughts are fairly accurate. This can also be helpful, as it highlights the need to problem solve and cope with a real problem.

Suzanne Examines the Evidence

Let’s look at how we could help Suzanne with her anxiety about the invitation to the principal’s barbecue. She identified her hot thought as No one will want to talk to me. Suzanne’s therapist explained the process of looking at the evidence, and Suzanne was willing to try.

Therapist: I want to start with looking for the evidence that supports your thought, No one will want to talk to me. What makes you think that it might be true?

Suzanne: Well, I know that I will feel anxious when I go to the barbecue.

Suzanne’s thought, I will feel anxious when I go to the barbecue, is not a fact. It is a prediction about how she will feel. Suzanne’s therapist wants to explore whether there are any facts that support her hot thought.

Therapist: I hear you will feel anxious, but I wonder if there are any facts that support your belief that no one will want to talk to you.

Suzanne: What do you mean?

Therapist: If I wanted to prove that no one would want to talk to you, I would have to back up my opinion with facts. For example, if you were in a court of law, the judge would look only at the facts. Does that make sense to you?

The therapist wants to be sure that Suzanne understands the idea of facts. Sometimes using the analogy of a court of law can be helpful.

Suzanne: What about the fact that I hardly know any of the other teachers, does that count?

Therapist: Of course, that is a fact. I wonder…how is it related to no one wanting to talk to you?

Suzanne: Well, none of them have made an effort to talk to me. I usually stand alone at recess and I eat lunch by myself also.

Therapist: Okay, so let’s write down what you just said, to be sure we don’t forget. How would you put that in your own words? (Either Suzanne or her therapist writes.) Other evidence that makes you think, No one will want to talk to me?

Notice that Suzanne’s therapist is gathering data; she is not refuting or problem solving.

Suzanne: I think it’s mainly at lunch and recess. Maybe also when I arrive in the morning, no one says hi to me, or smiles.

Use the Past to Understand the Present

It can be helpful to ask your client if she had any experiences in her childhood or past that support, or that are related to, her negative thoughts. Making the link between her history and her current thinking can help your client start to see that what was true in her past is not necessarily true in her current life.

Take a moment to think about how you could ask Suzanne about the relationship between any past events and her hot thought.

Therapist: Suzanne, is there anything in your past that would cause you to think, No one will want to be my friend?

Suzanne: Actually, when I was in high school, in my last year, there was a group of really awful girls who made my life miserable. They wanted to use my house for a drinking party when my parents were away for the weekend, and I said no. They spread awful rumors about me, and I lost almost all my friends. It was a horrible, lonely time in my life. I felt then that no one wanted to be my friend.

When a client discloses painful memories from her past, you need to decide if you want to focus on the memory or continue with the thought record. Generally, if it is the first time a client discloses a traumatic memory, I ask my client if she would like to focus on the memory. Suzanne disclosed a painful memory from high school that was upsetting, but not traumatic. Her therapist thought it was more important to continue with the thought record than to explore the high school memory.

Therapist: It must have been very upsetting to have this happen. Is that when the thought No one wants to be my friend started?

Suzanne: It was pretty awful. Yeah, that’s when I became more self-conscious and started worrying about people liking me. Before that, I just had a bunch of friends whom I hung out with.

Therapist: It sounds like it really changed your outlook. In another session, it might be important for us to talk about what happened in high school. For now, could we just put it down in the “Evidence for” column?

Let’s see how Suzanne filled in the “Evidence for My Thought” column of her Examine the Reality of Your Thoughts worksheet.

| Thought I want to examine: No one will want to be my friend. | |

|---|---|

| Evidence for My Thought | Evidence Against My Thought |

|

No one has made an effort to talk to me. I am alone at recess and lunch. Other teachers do not say hi when I get to school in the morning. In high school, some girls started rumors and I lost almost all my friends. |

|

Agenda Item #4: Find Evidence Against Negative Thoughts

Clients tend to focus on information that confirms their negative thoughts. Your job is to help your client focus on information she usually ignores and that challenges her negative thoughts. You can think of your client as living in a room filled with information, but only the information that supports her negative thoughts is lit; the rest of the room is in the dark. Your job is to use questions so that the whole room is in the light. Once the whole room is lit and your client sees all of the evidence, she can decide if her previous belief still makes sense.

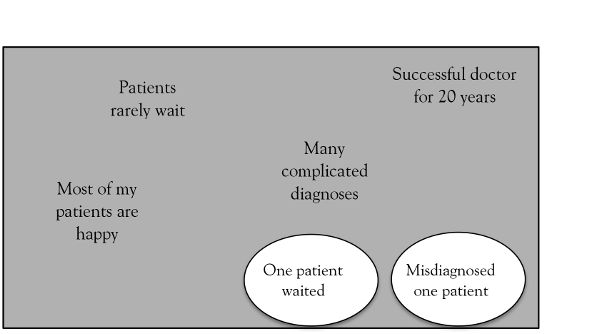

Figure 8.1 shows how a therapist used a drawing of lighting up a room to help her client Paula, who is a doctor, understand that she was only looking at information that confirmed her hot thought. In one of Paula’s therapy sessions she was very distressed and told her therapist she thought that she was not a good doctor. Her evidence for her belief was that this past week she had misdiagnosed a patient and another patient had been very angry because she had kept him waiting half an hour. Paula and her therapist looked at the evidence against her belief. Paula noted that she had been a successful doctor for twenty years, almost all her patients are happy, and she rarely keeps patients waiting; she also gave examples of many complicated diagnoses she made over the years.

Her therapist drew figure 8.2 to help Paula understand that she only sees information that confirms her belief that she is a bad doctor, and that all of the information that suggests she is a good doctor is ignored or kept in the dark. Her therapist told Paula they had to shine a light on all of the information.

Figure 8.1. Paula’s therapist shines some light on ignored information.

Figure 8.1. Paula’s therapist shines some light on ignored information.

There are three types of questions you can use to examine the evidence against a hot thought:

- Is there evidence that contradicts my negative thoughts?

- How probable is my negative prediction?

- Is there another perspective?

Evidence That Contradicts Your Client’s Negative Thoughts

I generally start by directly asking my client if she has any experiences that suggest that her hot thought is not true, or not true all of the time. When Suzanne’s therapist asked, “Have you had any experiences that suggest that people may want to be your friend?” Suzanne responded quietly, “I had some friends in my previous school.”

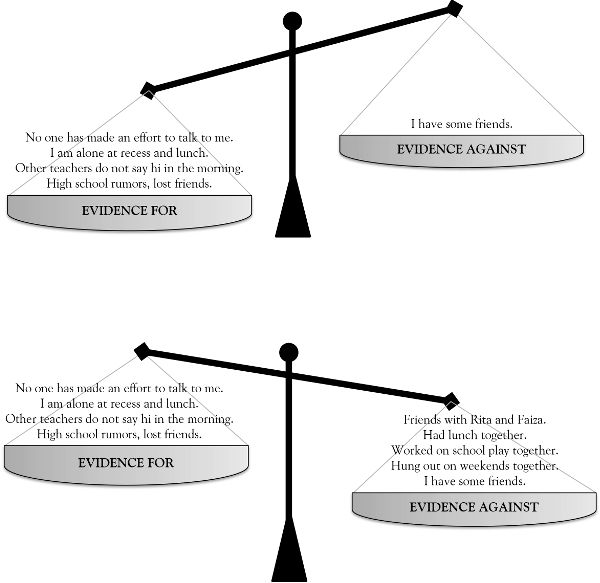

Evidence needs to be concrete and detailed. Examining the evidence for and against a negative automatic thought is similar to weighing evidence on a scale. On one side is the evidence for the negative thought and on the other side is the evidence against the negative thought. The evidence for the negative thought is usually very heavy and full of details. The evidence against the negative thought is often more abstract and lacking in details. It can feel light compared to the heavy evidence for the thought. The more your client can provide detailed examples of evidence against the negative thought, the more she will be emotionally engaged, and the more the evidence against the negative thought will weigh compared with the evidence for it.

Suzanne’s evidence against her hot thought is that she had “some friends.” This is not very strong or emotionally compelling evidence. To make the evidence more compelling, her therapist started by asking for specific examples, and then asked for details about the examples. Below are some of the questions her therapist asked.

- Can you give me examples of some of your friends?

- When you say you had “some friends,” can you tell me about them?

- What kinds of things did you do with your friends, both at school and outside of school?

- How did you know that they wanted to be your friend?

Her therapist discovers that Suzanne was friendly with many of the teachers at her previous school, but she had two good friends, Rita and Faiza. They generally ate lunch together and worked on the school play together. They often saw each other on weekends, and sometimes they would get together with their children and spouses. Suzanne thought they were funny, nice, warm people whom she had a good time with. Since she moved to her new school, she has seen less of them. They have often called to see if she wanted to do something on the weekend, but she’s been too tired. Faiza dropped by the other day with a cake she had made to cheer Suzanne up.

What was the effect of making the evidence more concrete and detailed? Did it become more emotionally compelling? When her therapist explores the details of her friendship with Rita and Faiza, Suzanne’s mood lifts. When her mood lifts, she is also more likely to remember other situations that challenge her negative automatic thoughts. Figure 8.3 captures the idea of making the evidence heavier: when Suzanne’s evidence against her hot thought No one will want to be my friend becomes more detailed and concrete, it becomes more compelling.

Additional Questions to Challenge Your Client’s Hot Thought

Clients may need additional help to think of evidence against their hot thoughts. The following questions are inspired by a number of wonderful CBT therapists, including Judy Beck (2011), Dennis Greenberger and Christine Padesky (2016), and Jackie Persons and colleagues (2001). You can download a Questions to Identify Evidence Against Negative Thoughts handout at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

- What would you say to someone who thought this way?

- What do you think a friend or someone who cared for you would say if he or she knew you had this thought?

- If you were in a better mood, what would you think?

- Five years from now, looking back, what might you think?

- Is there any information that contradicts your interpretation? Even small pieces of information?

- Is there any positive information that you are ignoring?

Let’s see how Suzanne’s therapist uses some of these questions.

Therapist: It sounds as if Faiza and Rita are really good friends. What do you think they would say if they knew you were thinking, No one will want to be my friend?

Suzanne: They would say it was ridiculous. That of course people would want to be my friend.

- Her therapist wants to expand this evidence.

Therapist: And if they really wanted to convince you, what might be some evidence they would tell you?

Suzanne: Well, they would probably remind me of all the friends I had at my previous school; they would also remind me that they like me.

Therapist: So they would remind you of your friends from your previous school and that they like you. And how is the fact that Rita and Faiza like you evidence against No one will want to be my friend?

The therapist starts with a summary statement and then relates the evidence to the hot thought.

Suzanne: (tentatively) Well I guess, if they like me, other people might like me?

Therapist: (smiling) Do you think that might be true?

Suzanne: (smiling) Yeah, I guess so.

Given that Suzanne’s mood has lifted a bit, she is more likely to remember other positive information.

Therapist: I am wondering if there is any positive information that you are ignoring.

Suzanne: (smiling) When I think of it, there is actually quite a bit. In college I had lots of good friends whom I still see, at least I saw them until I got depressed. I also have a bunch of friends from my neighborhood that I see on weekends, at the park.

How could you expand the evidence that Suzanne just discussed? Remember, ask for an example and then ask for details.

Suzanne’s evidence is starting to look very different!

| Thought I want to examine: No one will want to be my friend. | |

|---|---|

| Evidence for My Thought | Evidence Against My Thought |

|

No one has made an effort to talk to me. I am alone at recess and lunch. Other teachers do not say hi when I get to school in the morning. In high school, some girls started rumors and I lost almost all my friends. |

I had some friends in my previous school. Rita and Faiza are good friends; ate lunch together; worked on the school play; hung out on weekends; went out as couples; still call to see if I want to do something; Faiza brought a cake. Friends from college whom I still see Friends from neighborhood |

How Probable Are My Predictions?

Clients’ thoughts are often about the future and include negative predictions. Some examples might be No one will like me, I will fail the test, I will not get the job, or No one will like my Facebook post. When thoughts are about the future, you want to look for evidence about how likely it is that the negative event will occur. Below are the steps I usually use.

- Identify what your client fears will happen, and make the list as concrete as possible.

- Rate the probability that each feared event will occur.

- Examine the evidence for the probability that each feared event will occur.

- Rerate the probability that each feared event will occur.

I often use the following worksheet, How Probable Are My Predictions?, which you can download a full-scale version of at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

| How Probable Are My Predictions? | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What I Fear Will Happen | Probability That Feared Event Will Occur

(0–100%) |

Evidence That Supports the Probability | Evidence Against the Probability | Rerate the Probability That Feared Event Will Occur |

Here is Suzanne’s list of what she feared would happen at the barbecue:

- When I get there, everyone will be talking to each other, and no one will say hi to me.

- If I approach one of the new teachers, she will turn her back on me.

- I will stand there alone, with no one to talk to.

- If I go up to one of the other teachers, I will have nothing to say.

- Clear image of standing next to the barbecue grill, looking very awkward, holding a glass in my hand, and being all alone as everyone else talks together.

Rate the probability of each event occurring. Suzanne’s therapist asked her to rate from 0 to 100 percent how likely it was that each of these events would occur. Suzanne thought that the first three events, as well as her image, were very unlikely and rated them at 20 percent. Her therapist asked Suzanne to explain what made them unlikely. Suzanne laughed and said that it was a small group, and the principal would make sure everyone was talking to someone. She rated “having nothing to say” as probable, at 80 percent.

Examine the evidence. Suzanne and her therapist looked at the evidence for “If I go up to one of the other teachers, I will have nothing to say.” Suzanne explained that when she was anxious, she sometimes had difficulty finding something to talk about. This had happened at her husband’s holiday party. When Suzanne and her therapist examined the evidence against her prediction, she was able to think of many examples when she had been able to find something to say at social events, even if it had been difficult. Even at her husband’s holiday party she had found something to talk about with her husband’s colleagues.

Rerate the probability. After looking at the evidence, Suzanne rated the probability of having nothing to say at about 50 percent. Before and after probability ratings allow your client to see that there has been a decrease, even if the probability is not a 0.

You can see how Suzanne and her therapist completed the How Probable Are My Predictions? worksheet at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

Real and false alarms. Friedberg, Friedberg, and Friedberg (2001) have a wonderful exercise that helps clients look at whether their negative predictions actually occur. The therapist asks the client to list all of her worries for the coming week. The next week they check which worries actually happened. Most of the time, the majority of worries are “false alarms.”

Tolerance of uncertainty. Unless your client’s negative predictions are totally bizarre, no one can guarantee that they will not occur. Clients need to learn to tolerate uncertainty (Dugas & Robichaud, 2007). This can be hard, but a first step is talking honestly with your clients about accepting that life is uncertain, and that while not impossible, the probability of the feared events occurring is small.

Is There Another Perspective?

Sometimes a client’s negative thought is based on an overly negative interpretation of an event; you want to help your client find a more benign interpretation. Let’s look at an example. Raoul was upset because a colleague walked past him in the hall without saying hello. Raoul thought this meant that his colleague was avoiding him. Another possible interpretation is that his colleague was in a hurry or preoccupied.

Sometimes simply asking your client whether she can think of a different perspective is enough to start her thinking in a different way. However, sometimes you need to be more active. The following two approaches can help clients reach a more benign interpretation: (1) taking a close look at the facts of the situation and (2) exploring whether your client is blaming herself for something she has little or no control over.

Take a close look at the facts. Clients tend to focus on narrow information that reinforces their thoughts; your job is to help your clients broaden their perspective and look at all of the facts of a situation to see whether there is a more balanced interpretation.

Do you remember in the last chapter Raoul was extremely upset that he had been assigned to work with junior colleagues on a report? He was sure this meant that his boss did not respect him. Below are questions you can use to help your client examine her interpretation of a situation. You can download a Questions to Gather More Information about the Situation handout at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

- How did this situation come about?

- Who are the other people you will be working/interacting with?

- Is there any information that contradicts your interpretation? Even small pieces of information?

- Is there any positive information that you are ignoring?

- Have you ever behaved in a similar way? What was your motivation?

Let’s see what happens when Raoul’s therapist uses these questions to explore Raoul’s interpretation of the situation.

| Questions to Gather More Information about the Situation | |

|---|---|

| Questions | Raoul’s Response |

|

How did this situation come about? |

My boss approached me and said he would like me to work on this report, as he thought I had the needed expertise and had done this kind of work before. |

|

Who are the other people you will be working/interacting with? |

Two junior colleagues, who have been hired in the past two years. |

|

Is there any information that contradicts your interpretation? Even small pieces of information? |

Often senior people are asked to work with more junior people on reports. It is pretty common in the firm. |

|

Is there any positive information that you are ignoring? |

One of the junior people told me she was really glad to have me on the team, that she had heard great things about me. |

|

Have you ever behaved in a similar way? What was your motivation? |

In the past, I assigned a senior person to work on a project, to be sure that there was someone with the needed expertise on the project. |

Raoul’s therapist asked him whether this additional information had any implications for his thought that being assigned to the project meant that his boss did not respect him. Raoul replied that it might mean they wanted a senior person on this project. I am looking for a crack in my client’s beliefs. Just like water seeping through a stone, if you can get a small crack, it can spread.

Your Turn! Help Suzanne Take a Close Look at the Facts

Suzanne was very distressed that none of the teachers talked to her at recess. This was a key piece of evidence in her belief that no one would want to be her friend. Her therapist thought it would be worthwhile to see if there was a more benign interpretation.

- Therapist: One of the pieces of evidence you use to support your belief that none of the teachers would want to be your friend is that no one talks to you at recess.

Look at the three possible responses below and pick the one that will help Suzanne start to gather facts about the situation.

- It seems strange to me that they don’t talk to you; they sound like horrible people.

- How could you join one of the groups of teachers?

- Can you describe to me what happens at recess, what the other teachers do, and what you do?

Response #3 is the best question to help collect information on what occurs at recess. Depending on the answer, the therapist can follow up in different ways. Response #1 supports Suzanne’s interpretation of the situation. Response #2 starts a problem-solving process before the problem is clarified.

- Therapist: Can you describe to me what happens at recess and what the other teachers do?

- Suzanne: We each have an area we are responsible for. Actually, when I think of it, only the two teachers who are assigned to the jungle gym stand together. The rest of us stand alone in the school yard. Some of the other teachers might approach each other and say a few words. I just stand in the back of the school yard next to the swings.

Look at the three possible responses below and pick the one that will help Suzanne start to gain a different perspective.

- I hear that everyone is assigned to an area and that most of the teachers are standing alone; do I have it right?

- How much of a discipline problem are the children? What kinds of things do you find help with maintaining order?

- It seems to me that everyone is alone, and it doesn’t mean they don’t want to talk to you.

Response #1 is the best response. It is a summary of what Suzanne has told her therapist and is most likely to encourage her to consider a different perspective on what standing alone at recess means. In response #2, the therapist is gathering data about the situation, but the data is not relevant to Suzanne’s thought, No one wants to be my friend. In response #3, the therapist is telling Suzanne what to think.

Is your client blaming herself for something she has little or no control over? Many clients feel responsible for situations they have no control over or believe that the situation is a reflection of themselves, when it is at least partially due to external factors. Two of the questions I find most helpful are:

- Are there other factors that could contribute to this situation?

- Am I blaming myself for something I have little or no control over?

Let’s look at some examples of clients’ thoughts and see if there are other ways of looking at the situation. You can download a Other Ways of Understanding the Situation worksheet at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

| Other Ways of Understanding the Situation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Situation | Client’s Thought | Are there other factors that could contribute to this situation?

List all of the factors. |

What can I control?

Am I blaming myself for something I have little or no control over? |

|

Client’s 16-year-old son is using marijuana |

I am a bad mother. |

Many factors contribute to a child using marijuana, including availability, peer group, and laws. |

I can control telling my child not to use marijuana, but there are many other factors that contribute to marijuana use. Yes, I am blaming myself for something I do not have complete control over. |

|

Only 15 people came to my talk at the confer-ence; many people had over 25 at their talks. |

My work is not interesting or important. |

My talk was at the end of the day; it was a beautiful day outside; there were other similar talks at the same time. |

I can control how much work I put into my talk. I cannot control when my talk is scheduled or the weather. Yes, the other factors would also impact how many people came. |

Help Your Clients Reach Their Own Conclusions

Sometimes you remember information that challenges your client’s negative thought, but your client does not think of the information. Should you just tell your client? Let’s go back to the basic principles of Socratic questioning. You want to ask questions that draw your client’s attention to information she is not thinking about. Once your client has the information, you want her to draw her own conclusion.

For example, Raoul tells you that he has stopped contributing to meetings because he believes that “no one is interested in my comments.” You remember that a few weeks ago Raoul described making a comment in a project meeting, to which one of his colleagues responded, “That is the best solution anyone has suggested so far.” You could remind Raoul of his colleague’s comment and then tell Raoul that clearly people are interested in what he has to say. However, it is more effective if Raoul can reach his own conclusions. It is better to ask Raoul if he remembers what his colleague said, and then once Raoul has told you, ask him what his colleague’s statement might mean about his thought, No one is interested in my comments.

YOUR TURN! Help Cynthia Reach Her Own Conclusions

Cynthia was in therapy because she was having trouble with low self-esteem that was affecting many different areas of her life. She tells her therapist, “I was so embarrassed. I was at a party and a guy I know from work kept hitting on me. He kept telling me he wanted to go out with me and that I was beautiful. I just kept ignoring him. Men are only interested in me for sex.”

Cynthia’s hot thought is Men are only interested in me for sex.

Cynthia’s therapist tells her, “You are a wonderful woman; you deserve to find a great man. You have told me that lots of your male colleagues like and respect you.”

Instead of telling Cynthia what to think, what questions could the therapist ask that would help Cynthia reach her own conclusions?

From previous sessions her therapist knows that Cynthia is dating John, who frequently tells her that he cares about her. John always checks that she also wants sex before they have sexual relations. Cynthia has also talked about male colleagues who made comments indicating they respect Cynthia, especially Mike and Chris, whom she works closely with.

Your job is to think of questions that you could ask to help Cynthia reach her own conclusion about whether men are only interested in her for sex. You can find my suggestions in the appendix.

Consolidate the Evidence Against the Hot Thought

Most likely your client is used to thinking about the information that supports her negative thoughts and tends to minimize the information against her negative thoughts. If you want your client to emotionally connect to the information against her negative thought, it is important to review the information. Reviewing focuses your client’s attention on this information and starts to create new thought habits.

Usually I simply say, “Let’s review the information we have gathered.” If you have not written down the evidence, this is a good time to do so. You can say, “You collected some very important evidence about your thoughts. I think it would be helpful if we wrote it down, to be sure that we don’t forget it.” I encourage my clients to do the writing, as I think it helps with the review process. (If I am doing the writing, I repeat out loud what I am writing.) This also provides the client with a piece of paper she can take home and review as part of homework.

You can also use imagery to help evidence against a hot thought come alive (Josefowitz, 2016) by asking your client to form an image in her mind of the memories and situations that constitute the evidence against the hot thought. For Suzanne, an important piece of evidence against her hot thought was eating lunch almost every day with Rita and Faiza at her previous school. Her therapist asked Suzanne to form an image in her mind of eating lunch with her friends. She asked Suzanne to remember the lunchroom, the fun of being together, and how much they liked each other. Her therapist then went over the rest of the evidence, asking Suzanne to form an image for each example. When they had finished, the evidence felt much more real and emotionally engaging.

Agenda Item #5: Develop Balanced Thoughts

The final step in completing a thought record is evaluating the original hot thought and creating a new more balanced thought that takes all of the evidence into account. This is when you fill in the “Conclusion” section of the Examine the Reality of Your Thoughts worksheet. The basic question is, “Given all of the evidence, is your hot thought accurate, or does it need to be modified?” Here are some questions I regularly use. You can find Questions for a Balanced Thought at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

- When you look at all of the evidence, what does this say about your original hot thought?

- When you look at all of the evidence, what would be a more accurate thought?

- What might be a thought that captures all of the evidence?

- Let’s take a moment and look at all of the evidence. What did you learn?

- You initially interpreted the situation in a specific way. When you look at the evidence, is there another interpretation that either makes more sense or might be equally true?

- What would you tell someone who thought the way you did, and had all of this evidence?

Let’s look at how Suzanne initially completed the Understand Your Reaction worksheet and the Examine the Reality of Your Thoughts worksheet. Then, let’s look at the evidence that Suzanne and her therapist collected.

| Thought I want to examine: No one will want to be my friend. | |

|---|---|

| Evidence for My Thought | Evidence Against My Thought |

|

No one has made an effort to talk to me. I am alone at recess and lunch. Other teachers do not say hi when I get to school in the morning. In high school, some girls started rumors and I lost almost all my friends. |

I had some friends in my previous school. Rita and Faiza are good friends; ate lunch together, worked on the school play; hung out on weekends; went out as couples; still call to see if I want to do something; Faiza brought a cake Friends from college whom I still see Friends from the neighborhood |

Try to think of a balanced thought that captures all of the evidence. Write it down so you can compare it to the one Suzanne came up with.

Therapist: It seems to me that when you think, No one will want to be my friend, you are only considering the evidence that supports your thought. What happens when you consider all of the evidence?

Suzanne: I guess that it doesn’t seem to be so true.

Therapist: In what way is it not so true?

Suzanne: Well, I do have friends who like me and want to be my friend. I think one of the problems is that I have been avoiding my friends from my old school.

Therapist: I think you are right; we discovered that you have quite a few friends who like you. What would be a thought that captures all of the evidence?

Suzanne: Well, I guess, even though I haven’t yet made friends at my new school, I had friends in the past and there really is no reason I won’t have friends in the future.

Is Suzanne’s balanced thought better than the one you came up with? My clients often come up with far better balanced thoughts than I could ever have “told” them. Your job as a therapist is now easy—you just need to reinforce and consolidate the balanced thought.

There are two tasks left before completing the thought record. First, ask your client how much she believes the thought from 0 to 100 percent. Even if she gives a fairly low score, it is still a start to believing a new balanced thought. Second, ask your client if she believed the balanced thought, how would this affect her feelings, and ask her to rerate her original feelings. Suzanne believed her balanced thought 75 percent. She rerated her feelings Nervous: 5, Worried: 5, and Embarrassed: 4.

Consolidate the Balanced Thought

You have just spent a great deal of time and effort creating a balanced thought. It is worth spending a bit more time to consolidate this thought. First, be sure to smile and express interest in your client’s balanced thought. Your enthusiasm is reinforcing. Second, review the balanced thought in as many ways as you can. Here are some suggestions.

- Say the balanced thought out loud and add a compliment. For example, I might repeat the balanced thought and say, “I like the way the balanced thought captures all of the evidence.”

- Ask your client if she would like to write down the balanced thought so that she can remember it. My clients have written their balanced thoughts on coping cards, kept the balanced thoughts on their phones, or made the balanced thought into their screen saver.

- Ask your client to repeat the balanced thought out loud. Depending on the balanced thought, I might ask my client to try a more assertive tone, or a more compassionate, gentle tone.

- Ask your client to regularly review the balanced thought. I find it helpful to specify a set time to review, such as first thing in the morning.

Develop a metaphor or an image. Often a balanced thought is fairly long and complex and can be hard to remember. It can be helpful to create an image of the evidence that is the most compelling for your client and attach it to the balanced thought. An image that symbolizes the balanced thought, a metaphor, or even a shortened version can increase the emotional strength of the balanced thought and make it more memorable (Hackmann et al., 2011; Josefowitz, 2017). Here is Suzanne’s shortened version of her balanced thought: Hang in there, you will make friends again.

Use Balanced Thoughts to Create a New Image

When Suzanne’s therapist initially asked her about her thoughts and images, Suzanne reported that she had an image of herself alone in the principal’s backyard while the other teachers talked to each other. Once you have examined the evidence against the hot thought and created a balanced thought, you can go back and directly modify your client’s original image. Given the close connection between imagery and emotion, this can be a very powerful intervention. Let’s see how Suzanne’s therapist helps her create a new image.

Therapist: You started out with a very clear image of yourself standing in the principal’s backyard, awkward and alone, as the other teachers talked together.

Suzanne: That’s right, I wasn’t even aware that I had that image until you asked.

Therapist: Given the evidence that we just looked at, and your balanced thought, how accurate do you think your original image is?

Suzanne: (laughing softly) Probably not accurate at all.

Therapist: I think it would be really helpful if we could develop a more realistic image of what you think will happen. Could we try?

Suzanne: When I look at the evidence, and I really think about it, a more realistic image would be of my standing in the principal’s backyard talking to the other teachers, or at least being part of the group, even if I am not talking.

Suzanne’s therapist thought this was a good start for a new image. However, the initial negative image was very detailed and vivid. Suzanne’s therapist wanted the new image to be as compelling.

Therapist: Can you tell me a little bit more about this new image?

Suzanne: Well, I see myself standing there with my drink, and I am part of a small group. I am listening as one of the other teachers says something.

Therapist: Can you get a clear picture in your mind of this new image?

Suzanne: Yes, I can see it clearly (smiling).

Therapist: And how do you feel when you get this image?

Suzanne: A lot more relaxed about going, and a lot less depressed. Almost makes me wonder if it could be a good experience.

After they had developed this new image, Suzanne’s therapist asked her to consciously practice seeing the new image three times a day. They discussed specific times that Suzanne could practice. Her therapist told Suzanne that the practice could be very short, even a few minutes, but it was important to practice regularly.

Use Balanced Thoughts to Manage Stress

Balanced thoughts generally move your client away from extreme thinking, such as No one will like me, to more balanced thinking that generally helps with anxiety and depression as well as self-esteem. Balanced thoughts provide a more resilient attitude toward life’s stressors. As we discussed earlier, most clients have typical negative thoughts that tend to recur. This means that the balanced thoughts you develop for one situation will most likely also be relevant to other situations.

When Suzanne’s therapist asked if there were other situations where she had the thought No one will want to be my friend, Suzanne said she had this thought “all the time.” Her therapist asked for examples, and Suzanne replied that she often had these thoughts when she was alone at school during recess and lunch and at the end of the day when she left without saying good-bye to anyone. If you look at all of these situations, the thought No one will want to be my friend leads to Suzanne feeling depressed and withdrawing from the other teachers, making it almost impossible to make friends, leading to a vicious cycle where it seemed true that no one wanted to be her friend.

Suzanne’s therapist asked her, “Instead of thinking, No one will want to be my friend, if you thought your new balanced thought, Hang in there, you will make friends again, how do you think you would feel?” Suzanne smiled as she responded that she would be less depressed. Suzanne and her therapist problem solved how she could remember her new balanced thought in the other situations when she starts thinking, No one will want to be my friend. Suzanne’s therapist also encouraged her to notice if she had any unrealistic images in these situations.

Sometimes, completing a thought record influences how your client wants to behave. After Suzanne developed a balanced thought, she turned toward her therapist and said, “I have been really silly about the barbecue. I would like to go. It would be good to meet the other teachers, and there is no reason to be so anxious.” Let’s see how Suzanne’s therapist could help her use her balanced thought.

Therapist: When you think about it, you would like to go to the barbecue.

Suzanne: I think it would be a good thing to do. I want to make friends at my new school, and it’s just silly to avoid social events because of my anxiety.

Therapist: After we did the thought record, you came up with a really good balanced thought; do you remember what it was?

Suzanne: Yes, it was, Hang in there, you will make friends again.

Therapist: That’s right. I am wondering if you could remember your balanced thought when you think of going to the barbecue, if that would help with your anxiety.

Suzanne: I think it would.

Therapist: Sounds like a great plan.

Checklist of Common Problems with Thought Records

Thought records are generally an effective intervention; however, some are more helpful than others. Below is a checklist you can use to check that a thought record is well done. You can find a copy of Checklist of Common Problems with Thought Records at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

Is the situation a factual description of what occurred?

Did my client identify and rate his or her feelings?

Did my client identify his physical reactions?

Is the behavior a factual description of what my client did?

Is the thought my client wants to focus on a hot thought?

Is the thought about self, others, or the future?

Is the thought related to his or her negative feelings?

Does the evidence against address the hot thought?

Does the balanced thought address the hot thought?

It is important that the evidence you gather challenge the hot thought you are working on. For example, a colleague had passed Raoul in the hall and had not said hi. Raoul thought, My colleague is avoiding me. His evidence against his thought was, My bowling buddies are happy to see me. This evidence will help Raoul feel better, but it is not related to the thought, My colleague is avoiding me. In this situation you need to keep exploring Raoul’s thoughts using Questions to Identify Evidence Against Negative Thoughts to find evidence related to the hot thought you are working on.

It is equally important that the balanced thought directly address the hot thought. For example, if the original thought was about self, the balanced thought needs to be about self; if the original thought was about others, the balanced thought needs to be about others. When Raoul was assigned to work with junior colleagues, his original thought was My boss doesn’t respect me. After examining the evidence for and against, his initial balanced thought was I work very hard and do a good job. This is a generally helpful thought that will increase Raoul’s positive mood. If I were his therapist, I would be delighted that he was able to have such a positive thought about himself. However, the hot thought was about others (his boss), and the balanced thought needs to also be about others. A better balanced thought would be, Even though I was asked to work with junior colleagues, this does not mean my boss does not respect me. There is a lot of evidence that my boss still respects me and my work.

It is helpful to keep this list in mind when examining your clients’ thought records. Take a moment after your session is over and on your own review your client’s thought record, using the checklist. After you have used it a few times, it will become second nature.

Homework: Practice CBT

Before continuing with the next chapter, take some time to try the homework.

Apply What You Learned to a Clinical Example

Complete the following exercises.

- Exercise 8.1: Suzanne Is Upset with Her Husband

- Exercise 8.2: A Therapist Is Having a Bad Day

- Exercise 8.3: Suzanne Is Asked to Be a Maid of Honor

- Exercise 8.4: Suzanne Reviews Her Balanced Thought

- Exercise 8.5: Common Problems with Thought Records

Apply What You Learned to Your Own Life

I think you only become a committed CBT therapist when you experience how helpful it can be to identify your own negative thoughts, step back and examine the evidence, and then develop a balanced thought.

Homework Assignment #1 What Is the Evidence?

This coming week, when you have a strong emotional reaction, try to identify the situation, identify and rate your feelings, and then identify your thoughts. Choose one thought to examine using Questions to Identify Evidence Against My Negative Thoughts. Record your answers on the following worksheet.

| Examine the Reality of Your Thoughts | |

|---|---|

| Thought I want to examine: | |

| Evidence for My Thought | Evidence Against My Thought |

| Conclusion or thoughts that consider all the evidence: | |

Homework Assignment #2 How Probable Is My Prediction?

This coming week when you are anxious, notice your negative predictions. Rate the probability that each will occur, look at the evidence, and then rerate the probability. Try to use the How Probable Are My Predictions worksheet.

Homework Assignment #3 Is There Another Interpretation?

This coming week when you are upset by what someone did to you or by a situation, ask yourself if there is a more benign interpretation. Ask yourself if you are considering all of the facts of the situation. Are you blaming yourself for something you have no control over? Try to use the Other Ways of Understanding the Situation worksheet.

Apply What You Learned to Your Therapy Practice

It is time to start asking your clients to examine the evidence for their thoughts. Try to help a client identify her trigger situation and then identify and rate her feelings and thoughts. Once you have identified a central thought, introduce the idea of looking for evidence and use the Questions to Identify Evidence Against My Negative Thoughts. Make sure that the evidence is concrete and addresses the hot thought. Use the Examine the Reality of Your Thoughts worksheet to record your client’s responses.

Let’s Review

Answer the questions under each agenda item.

Agenda Item #1: What are thought records?

- What are the essential steps in a thought record?

Agenda Item #2: Explain looking for evidence.

- How could you introduce looking for evidence to your clients?

Agenda Item #3: Find evidence that supports negative thoughts.

- Why is it important to look for facts that support negative thoughts?

Agenda Item #4: Find evidence against negative thoughts.

- What are three questions that will help gather information against a client’s negative thoughts?

Agenda Item #5: Develop balanced thoughts.

- How could you consolidate a balanced thought?

Figure 8.3. Weighing Suzanne’s evidence.

Figure 8.3. Weighing Suzanne’s evidence.