Chapter 10

Behavioral Activation—Action Plans for Depression

In the last chapter we covered problem solving. Did you notice your clients’ problem orientation? Did you have a chance to try problem solving in your own life or with any clients? What was it like to consciously evaluate different solutions? Was it hard not to jump in and solve your clients’ problems?

Set the Agenda

In this chapter you will learn how to help your clients who have depression by increasing their activity level to improve their mood. The technical term for this intervention is behavioral activation.

- Agenda Item #1: How does behavioral activation work?

- Agenda Item #2: Help your clients understand their depression.

- Agenda Item #3: Monitor your clients’ daily activities.

- Agenda Item #4: Plan activities that increase positive moods.

- Agenda Item #5: Graded task assignments.

- Agenda Item #6: Increase well-being.

Work the Agenda

Behavioral activation is primarily a treatment for depression. It is based on the premise that when your clients change their behaviors, and increase activities that promote pleasure and a sense of competence, their mood will improve.

Agenda Item #1: How Does Behavioral Activation Work?

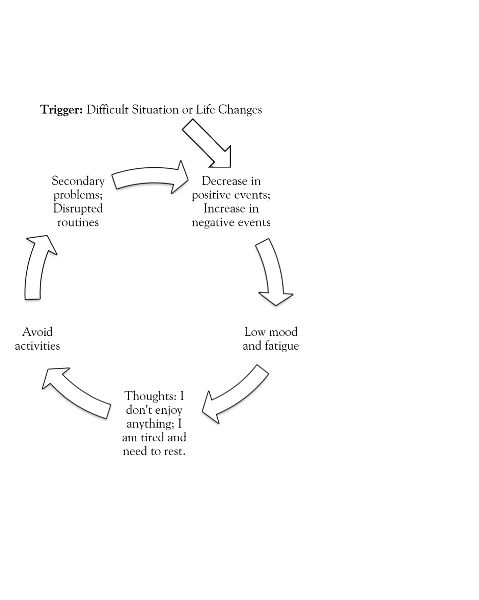

You can think of depression as a cycle that is caused and maintained by avoidance and a lack of positive reinforcement. Depression starts with changes in a client’s life that lead to a decrease in events that she enjoys and an increase in unpleasant events. As a result of these changes, your client’s overall mood declines and activities she used to enjoy are less pleasurable. Clients start avoiding activities such as seeing friends and family and pursuing hobbies, exercise, or leisure activities. The more clients avoid activities that might lift their mood, the less contact they have with positive reinforcements. The less contact with positive reinforcements, the more down they feel and the less they feel like doing anything (Martell, Dimidjian, & Herman-Dunn, 2010).

When clients become less active, their overall routine is disrupted, which may lead to sleep problems, poor appetite, and generally feeling out of sync with their environment, all of which exacerbate depression (Dimidjian, Barrera, Martell, Muñoz, & Lewinsohn, 2011). The more your clients are caught in this cycle of depression, the more they disengage from their normal life and the more likely they are to develop secondary problems. For example, the student who is too depressed to attend baseball practice may eventually be kicked off the team. Figure 10.1 shows how the cycle of depression works.

Figure 10.1. Cycle of depression.

Figure 10.1. Cycle of depression.

Breaking the Cycle of Inactivity and Depression

Behavioral activation interrupts the cycle of depression by directly targeting avoidance and encouraging clients to engage in mood-boosting activities. Clients identify activities that (1) are enjoyable, (2) increase their confidence or sense of mastery, or (3) are functional in that they decrease the negative consequences of avoidance. The therapist works with clients to schedule these activities into their week in a step-by-step manner and uses the problem-solving process to address any obstacles (Martell et al., 2010). As clients start to engage in pleasurable activities, their mood improves. As clients feel better, they have more energy, they stop wanting to avoid activities, and they engage in healthy routines. In short, a mood-boosting cycle starts.

Overview of Behavioral Activation

The formal goal of behavioral activation is for your clients to return to their pre-depression level of functioning. I prefer to tell my clients that our goal is to help them have a life they enjoy. The focus is to actively encourage clients to engage in activities even though they “feel” like avoiding or resting. It seems to me that folk wisdom often captures the essence of behavioral activation. My Aunt Tanya, who is eighty-eight, always told me, “No matter what, get up every morning and put on your makeup, and before you go to bed at night, have a sip of vodka.” In other words, according to Aunt Tanya, no matter how you are feeling, get up and face the world, and before the day ends, do something nice for yourself.

Generally, the behavioral activation process unfolds in the following order.

- Understand your client’s depression in relation to changes in his or her daily activities.

- Monitor your client’s daily activities.

- Plan activities that increase positive mood.

- Monitor your client’s mood before and after activities.

- Problem solve obstacles.

- Establish healthy routines and prevent setbacks.

Is Behavioral Activation Effective?

Even though I have practiced behavioral activation for many years, when a client with severe depression comes into my office, I often find myself thinking that behavioral activation will not be enough. How can adding pleasurable activities be sufficient to help this very depressed client? But rather than believing my automatic thoughts…I look at the evidence!

Over the past three decades, numerous studies, including a number of meta-analyses, have consistently demonstrated that behavioral activation is an effective treatment for mild, moderate, and severe depression (Dimidjian et al., 2011; Soucy-Chartier & Provencher, 2013). This is true for children, teens, and adults of all ages. Behavioral activation alone has been found to be as effective as treatments that include both behavioral and cognitive interventions, such as identifying and challenging negative thoughts (Dimidjian et al., 2006; Richards et al., 2016). There is some indication that if clients are severely depressed, therapy provided over a sixteen-week period that includes only behavioral activation is more effective than therapy that includes behavioral and cognitive interventions. Behavioral activation is also an effective intervention for relapse prevention (Dobson et al., 2008). A recent study found that clients with complicated bereavement also responded positively to behavioral activation (Hershenberg, Paulson, Gros, & Acierno, 2014).

Agenda Item #2: Help Your Clients Understand Their Depression

A client who is depressed often starts therapy saying, “What is wrong with me? I used to be so strong” or, “I think I am going crazy, I just feel like crying all day.” You want to help your client understand that her depression is related to a lack of mood-enhancing activities and is not a personal failure.

You can use the cycle of depression as a model for gathering information that will help your clients understand the factors that caused and maintain their depression. If your clients understand that their depression is related to a lack of pleasurable activities in their lives, they will be more motivated to engage in mood-boosting activities. This is important, as you are going to ask your clients to engage in activities even if they don’t “feel like it.”

Start with looking at the changes in your client’s life that preceded her depression, in particular, decreases in reinforcing and/or pleasurable activities and increases in unpleasant activities. You also want to look at how your client coped with these changes, and the role of avoidance. The two main questions I ask my client are:

- What life changes occurred prior to your depression?

- How did these changes affect your daily life activities in relation to an increase or decrease in pleasurable activities?

Suzanne’s Cycle of Depression

Suzanne started therapy saying she didn’t know what was wrong with her. She had a great house, great kids, a good job, and a great husband, but she was just so overwhelmed that she didn’t enjoy life anymore. She cried softly as she told her therapist that she wasn’t coping.

In chapter 2 we listed the stressors and recent changes in Suzanne’s life that happened prior to her depression.

- Suzanne started teaching at a new school. The school is a thirty- to forty-minute commute from home; she does not know the other teachers, who form a tight group.

- Her mother-in-law is no longer able to babysit.

- Genia, her best friend, moved away.

Let’s see how her therapist uses the two questions we just identified to understand Suzanne’s depression.

Therapist: It sounds like there have been a lot of changes in your life. I am wondering if we could spend a moment and think about how each change has affected your life. Which one should we look at first?

Suzanne: Well, I think the really big one is the new school.

Therapist: I think it would be helpful to look at how your life has changed since starting at the new school. I want to look at activities you stopped doing, and activities you started doing because of the new school.

The therapist instills hope by starting with, “I think it would be helpful.” Notice her therapist did not ask Suzanne how she feels about the new school. She asked her to look at how her life is different.

Suzanne: One of the biggest changes is the morning. I used to walk to school; it was about fifteen minutes each way. I now spend forty-five minutes commuting. The extra thirty minutes I used to have meant that I had time to get the kids ready in the morning. Now everything has to be ready the night before. The kids have to be completely ready to be dropped off at my neighbor’s home by 7:30. It’s really hard getting them up, dressed, and fed. My neighbor takes them to school. My husband leaves early for work and can’t help.

Therapist: That sounds like a really big change to your morning routine.

Suzanne: Yes, I used to enjoy the mornings—it was a nice time with the kids, and I liked the walk to school. Now it is just so stressful.

The therapist makes a supportive comment, and Suzanne goes on to elaborate how her life has changed.

Therapist: I want to start making a list of the ways your life has changed. I think it will help us understand your depression and how to help you. What would you put down?

Notice how her therapist instills hope. The therapist asks Suzanne what she would put on the list.

Suzanne: Well, I guess, I no longer have the fifteen-minute walk to school, I no longer have a nice time with my kids in the morning, and actually, I rarely eat breakfast, I am so frazzled. I am often starving by the time I get to school.

Therapist: I think that’s a really good list of all the things that you are no longer doing. What about anything that you now do because of the new school that you were not doing before?

Suzanne: Well, I guess I have to be really organized the night before, which I find hard. I make my daughter’s lunch, put out the kids’ clothes, and make sure I am all organized for school. Also, I have to be really strict with the kids, as I am on a tight schedule. Which means I yell more to get them going in the morning. I also have the long drive to work, which I hate. I spend the whole time in the car thinking about what a bad mom I’ve become, how I yelled at the kids once again, and how I wish I were back at my old school. It’s just awful.

Therapist: Sounds like a lot of changes. When we look at how different your morning is now to how it used to be, what are your thoughts?

Note that the therapist first asked Suzanne what had changed, second asked her how the change had affected her daily life, and third asked her what she thought when she looked at the changes.

Suzanne: Well, no wonder I am depressed; it sounds like an awful way to start the morning.

By examining how her morning has changed, Suzanne has shifted from “something is wrong with me that I am depressed,” to realizing that the changes in her morning routine may be contributing to her depression.

Therapist: I think you said something important. Seems like the change in school caused a lot of other changes in your life and had a negative effect on your morning routine and mood. I think we are discovering some important information. I want to see if there are other ways that starting at the new school has impacted your life.

Notice how Suzanne’s therapist reinforces her awareness that her morning routine is impacting her mood. Also notice how the therapist keeps Suzanne on track with the task.

Suzanne used to spend time with other teachers, who were her friends, and now she sees few of her friends. She had enjoyed being involved in the school play and had received a lot of positive feedback from many people in the school. She was well known as a popular teacher. At her new school she participates in no extracurricular activities and knows none of the other teachers socially. She gets home late from work, tired and frazzled from the drive.

Suzanne had not realized that since her mother-in-law had become ill and could no longer babysit, she and her husband had practically stopped going out in the evening. It had been ages since they had seen many of their friends. Suzanne also realized that since Genia had moved away, she had stopped her weekly walks and talked to her friend much less. Suzanne was surprised when she looked at the impact of all the changes in her life.

Use a Written Summary

After I have explored with my client how her life has changed, I find it helpful to provide a written summary. Sometimes I draw the cycle of depression and together we look at how it is related to my client’s specific situation. Other times I use the Understand Your Depression worksheet, which you can download at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501. The worksheet gives your client an overview of how her activities have changed since she became depressed. When Suzanne looked at her Understand Your Depression worksheet, it made sense that the changes in her activities were affecting her depression.

| Understand Your Depression | ||

|---|---|---|

|

Changes or stressors in your life prior to your depression? New school, mother-in-law no longer babysitting, and Genia, her best friend, moving away. Since these changes or stressors, how have your activities changed? Complete the form below. |

||

| Increased Since Life Changes or Stressors | Decreased Since Life Changes or Stressors | |

| Activities I enjoy or that provide pleasure or mastery |

None |

Walk to school; nice time with children in the morning; going out with husband and seeing friends; Sunday walk with Genia; talking to Genia |

| Activities I do not enjoy |

Getting ready the night before; long drive to work; getting up early and getting children ready |

None |

| Exercise |

No walk to school, no Sunday walk |

|

| Spending time with friends |

Stopped seeing school friends, Genia moved away |

|

| Spending time with family |

See mother-in-law more, as she has been ill |

Less time with children in the morning; less time with husband overall |

| Leisure or hobbies |

None |

No school play; no other extracurricular activities |

| Smoking, overeating, alcohol or drug use |

None |

|

| Routines related to eating and sleeping |

No breakfast routine, often fall asleep in front of TV |

|

Use an Analogy

I sometimes use a flower analogy to help my client understand her depression. This analogy was inspired by Melanie Fennell’s virtuous and vicious flowers (Fennell, 2006). I explain that feeling happy is similar to a brightly colored flower with lots of petals. I then draw a flower with a circle in the middle and petals around the circle. I ask my client to fill in each petal with an activity she did before she became depressed that she enjoyed or gave meaning to her life. I look for healthy routines; social activities with colleagues, friends, and family; activities that are pleasurable or meaningful; and activities that lead to a sense of competence or mastery.

Once my client has completed filling in her flower, I ask her to draw an X through all the petals that have changed since the depression. Usually, almost all of them are gone. What was once a full bloom is often only a few petals.

With some clients, instead of a flower I draw a picture of a wall. I use bricks to build a strong wall; if you take out too many bricks, the wall will fall, or have big holes.

Suzanne’s therapist used the flower analogy, and Suzanne was surprised to see her flower. Her depression was making more and more sense to her. Her therapist explained that together they would help Suzanne start to add petals back into her life so that she could start to feel better. Suzanne said this was a good idea, but added that she couldn’t imagine where to begin. Her therapist assured her they would work together and go slowly.

Your Turn! Understand Mayleen’s Depression

Below is a description of Mayleen, a fifty-eight-year-old woman who has come to therapy because she is currently depressed. Try to complete the Understand Your Depression worksheet with the information below. You can see my answers in the appendix.

- Mayleen is a successful sculptor. She lives alone, has never married, and has no children. Two years ago her mother became ill, and Mayleen has been very involved in her care.

- Mayleen’s mother lives alone in the town where Mayleen grew up, about three hours away. Mayleen left when she was eighteen and no longer has any friends or other family who live there. She spends four days a week visiting her mother and attending to her needs, looking after the house, and taking her to doctor’s appointments. Mayleen is happy that she is able to care for her sick mother but feels lonely when she visits. She and her mother watch a lot of daytime TV, which Mayleen finds boring.

- Over the two years that her mother has been ill, Mayleen has become increasingly depressed and feels guilty about not spending all her time caring for her mother. She has stopped seeing many of her friends, has given up exercise, and has almost completely stopped sculpting, as she believes there is no time for these activities, and she is so tired most of the time.

Agenda Item #3: Monitor Your Clients’ Daily Activities

Behavioral activation involves asking your clients to engage in pleasurable activities. Sounds easy. The difficulty is that depressed clients don’t feel like doing anything. They will tell you, “Nothing helps.” You are going to ask your clients to act according to a plan rather than according to how they feel. If your clients can see the connection between an increase in their activity level and an increase in their mood, they will be more motivated to add pleasurable activities to their lives, even if they don’t “feel” like doing them.

The easiest way for clients to see the connection between their mood and specific activities is to monitor their daily activities and rate their moods. I ask clients to complete a Daily Activities Schedule (available at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501), where they write what they do, hour by hour, and rate their mood. I usually complete the first day of the Daily Activities Schedule during the therapy hour. That way, I am sure my clients understand what to do. (If the session is early in the morning, we complete it for the previous day.) Then for homework I assign the Daily Activities Schedule for the rest of the week.

Here is how I introduce the Daily Activities Schedule. I explain both the rationale behind the intervention and what we will be doing.

I think it is important to understand how you spend your days, and if your mood changes with the types of activities that you do. I have a Daily Activities Schedule where you can write down what you do throughout the day, and rate your mood. That way, we can see whether there are times during the day when you feel better, and times when you feel worse. We are going to try and increase the times you feel better and learn how to cope with the times when you feel worse. Does this make sense to you?

Let’s take today and see if we can complete the schedule together. Is that okay with you? What time did you wake up? If you had to rate your mood from 1 to 10, with 10 being the most depressed you have ever been, and 1 being not at all depressed, where would you rate your mood when you woke up today?

I then take my client through her day, rating her mood during each activity.

Your Turn! Practice in Your Imagination: Explain a Daily Activities Schedule

Before you start, rate from 1 to 10 how comfortable you are explaining a Daily Activities Schedule to a client who is depressed. At the end of the exercise, rate your level of comfort again to see whether it changed. Now, let’s try this exercise.

Choose a client who is depressed and who you think would benefit from using behavioral activation. Try to get a picture of him or her in your mind. Imagine yourself in your office with your client. See your office; notice the sounds and smells in the room. Imagine that you want to introduce a Daily Activities Schedule. Read over how I explain using a Daily Activities Schedule while imagining yourself saying the words. You can also use your own phrases. Imagine getting out the Daily Activities Schedule and explaining it to your client. Now, imagine explaining the Daily Activities Schedule two more times with the same client. Each time, imagine that your client responds positively.

What Did Your Client Learn?

The next step is to use the Daily Activities Schedule to help your client discover an activity/mood relationship and to decide which times of day to target and which activities to introduce or expand. I start with asking my client about the general experience of completing the Daily Activities Schedule and then ask whether she learned anything in the process. I then go over Questions to Explore a Mood/Activity Relationship (Martell et al., 2010). When I first started doing behavioral activation, I kept these questions next to me. You can download a copy at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

- Do you see an activity/mood relationship?

- What activities help you feel better?

- What activities or situations are connected to a low mood?

- What time periods are you most at risk for a low mood?

- Do you have any routines that help you maintain a positive mood?

- Is there anything you are avoiding?

Below is the Daily Activities Schedule that Suzanne completed and brought to therapy. She rated her depression from 1 to 10, 1 being not at all depressed and 10 being the most depressed she had ever been.

What Did Suzanne Learn?

Before looking at Suzanne’s answers to Questions to Explore a Mood/Activity Relationship, examine her week and see how you would answer the following questions. After each question, I have included Treatment Implications, where I encourage you to think about how you would use the answers to the questions in guiding future therapy.

Do you see an activity/mood relationship? What activities help you feel better? What activities or situations are connected to a low mood? When Suzanne reviewed her Daily Activities Schedule, it struck her that she was doing almost nothing fun. She was surprised that when she was more active, her mood improved. In particular, socializing with other people helped her feel better. Suzanne also noted that she felt better when her husband was home and that she felt fairly good most of the time at school. Suzanne had always thought that she felt better on the weekends because she slept more and was away from school. After looking at her Daily Activities Schedule, she wondered if she felt better because she was more active and spending time with her husband, friends, and family.

Suzanne noted she was very depressed during her drives to and from school. She explained that she spent most of the drive thinking about how horrible the morning had been and how she wished she was back at her old school. Watching TV at night with her kids and without her husband was also a low time. She also noted how much she disliked getting ready for the next day and how hard she found the morning routines.

- Treatment implications: How would you use Suzanne’s answers to the questions above to reinforce the importance of adding pleasurable activities to her life?

What time periods are you most at risk for low mood? Suzanne noted that mornings were particularly bad. When she wakes up, she lies in bed and thinks about what a bad mother she is and how her husband must be fed up with her. She has images of him leaving her and of being alone and miserable. Suzanne had not realized how depressed she was every morning and how hard it was for her to get the kids ready on a tight time schedule. She also noted that the nights she was home alone with the kids were particularly hard, and she was often depressed.

- Treatment implications: What time period would you target first for adding pleasurable activities?

Do you have any routines that help you maintain a positive mood? Suzanne could not see any routines that helped her feel better. She realized how different that was from the previous year, when she had a good morning routine, walked to school, and regularly saw friends. Her therapist noticed that she put her children to bed at a regular and appropriate time. Suzanne and her husband also went to bed at a regular time and early enough that they got eight hours of sleep. Her therapist thought that these were real strengths and important routines.

- Treatment implications: How would you use this information in therapy?

Is there anything you are avoiding? Suzanne could not think of anything she was avoiding. She mentioned that she did not go out with her friends much anymore, but that was because she was so tired all of the time.

- Treatment implications: From a behavioral activation perspective, do you think she is avoiding friends?

Agenda Item #4: Plan Activities That Increase Positive Moods

After looking at her schedule, Suzanne agreed it would be a good idea to start a mood-boosting plan. Her therapist explained that when you are depressed, doing pleasurable activities is like taking medicine—you do it because you know it will help, not because you want to. As a therapist, you need to encourage your clients to follow their mood-boosting plan rather than their depressed feelings.

Activities that Encourage Mastery and Pleasure

In behavioral activation you want to increase activities that provide your client with a sense of mastery or competence and pleasure. However, such a general statement does not provide much guidance for therapy. I suggest activities in the following categories to help boost a client’s mood. It is important to remember that this is a very individualized process, as activities that provide a sense of mastery or competence and pleasure are different for every individual.

Activities of daily living. First and foremost, I want to be sure that my client is accomplishing the basic business of living, including feeding herself, cleaning her clothes, getting enough sleep, doing basic chores, and addressing responsibilities to family, friends, or work such as taking care of children or completing minimal work tasks. For example, Suzanne is often too frazzled to eat breakfast and arrives at school starving. She often eats a chocolate bar or is hungry all morning. It would be important for her therapist to help Suzanne make an effort to eat breakfast.

Social contact. People vary in how much and what kind of social contact they want, but everyone needs some. When clients become depressed, they usually withdraw from family and friends. It can be hard to re-engage. You want to start slowly with small steps.

Exercise. There is increasing evidence that regular exercise boosts your mood and can counter depressed feelings (Trivedi et al., 2011). Exercising outdoors may lift your mood even more than exercising indoors (Barton & Pretty, 2010). This makes total sense to me; I am far happier walking outside on a beautiful spring day than using the treadmill in the gym. In fact, I am even happier if I walk outside with a good friend…and pick up a coffee (and maybe even a cookie!).

Clients vary tremendously in how much exercise they want to do. Generally, any increase in activity is good. With some clients I have started by encouraging them to go outside for five minutes.

Pleasurable activities. When clients are depressed it can be hard to find activities that they find pleasurable. Here are some suggestions.

- Build on existing activities. Identify mood-boosting activities your client is already doing and expand the activity. For example, if your client enjoyed talking to a friend about the recent political situation, can she see this friend more often? Can she contact another friend? Maybe the stimulation of discussing politics increased her mood. Could she read the newspaper or listen to a podcast?

- Try activities your client used to enjoy before she was depressed. She may be surprised at how much she still enjoys them. Just make sure your client doesn’t expect to enjoy these activities as much as before.

- Use the Pleasurable Activities List, which you can download at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501. The list can start clients thinking about possible activities they don’t usually do but might like to try.

- Choose activities that lead to a sense of mastery or competence. People tend to enjoy doing things they are good at. You also want to address any avoidant behavior that is likely to create additional problems, such as avoiding completing a work project or enrolling children in camp.

- Encourage activities that are consistent with your client’s values and are meaningful. For example, volunteering may be enjoyable because it is related to a client’s values.

Practice being mindful. I encourage my clients to gently put aside their critical mind and allow themselves to concentrate on the activity in the moment. For example, if a client is walking outside, I encourage her to notice the fresh air, see the flowers, and feel the wind. Don’t tell your client to stop thinking negative thoughts. When we tell ourselves to stop thinking something, the thought bounces back stronger. Some of my clients like the idea of taking a holiday from their negative thoughts.

Guidelines for Effective Activity Plans

Suzanne wanted to start with an activity that would have an immediate effect on her mornings, as she arrives at school already very depressed. She decided to try listening to music and podcasts in the car on the way to work as a way to boost her mood.

Suzanne also wanted to add telephoning Genia, her best friend; contacting Rita, her friend from her previous school; and seeing her mother-in-law. She set a time when she would call Rita and Genia. Rather than set a specific time to see her mother-in-law, Suzanne wanted to see how her weekend developed. Sometimes it is helpful to set specific times for activities, but sometimes clients want a more flexible schedule. If we were flexible in terms of when an activity would get done, and my client didn’t do the activity, the next week I try to set a specific time. Suzanne was not optimistic that these would make much difference to her mood, but she was willing to try.

Though these activities sound great, often clients don’t do the activities they plan. Activities that follow the guidelines below have a better chance of being done. You can find a Guidelines for an Effective Activity Plan handout at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

- Was the plan developed collaboratively with your client?

- Is the plan specific and concrete?

- Is the plan doable?

- Is the plan naturally reinforcing?

- Can the plan be part of a regular routine?

Developed collaboratively. I start by asking, “What would be a good activity to add to your week that would help you start to feel better?” Clients often have very good suggestions; however, sometimes they need help thinking of good activities. If you suggest the activity, try to involve your client in tailoring your suggestions to her situation. The key is to develop the activity with your client, not for your client.

Suzanne’s therapist was careful that the activities were either Suzanne’s idea or developed together.

Specific and concrete. Use the same criteria we used to decide whether homework was sufficiently specific and concrete: Is there a specific behavior your client is going to do? How often will your client do the activity? Where and when will your client do the activity?

Suzanne’s activities are specific and concrete. Suzanne wanted some flexibility in planning to see her mother-in-law. That seemed fine to her therapist. Not every activity has to be rigidly scheduled.

Doable. Start at your client’s current level of activity, not where she would like to be, or where she used to be. Start small, so that your client can experience success. I always ask if the activity “feels doable.” I also check if my client has everything she needs to complete the activity. Ask if your client foresees any obstacles and problem solve how to overcome them.

When Suzanne’s therapist checked if the activities felt doable, Suzanne said that listening to music while driving to and from school felt doable. However, the idea of finding a podcast, downloading it, and then concentrating on someone talking felt overwhelming. They decided she would focus on listening to music.

Naturally reinforcing. Choose activities that are intrinsically enjoyable or that your client will receive positive reinforcement for doing. For example, fifteen minutes of playing a board game with your child is more naturally reinforcing than fifteen minutes of doing dishes. This is particularly important in the beginning, when you want your client to experience positive results and stay motivated.

The activities Suzanne and her therapist chose were naturally reinforcing. Suzanne likes music and enjoys spending time with Rita, Genia, and her mother-in-law.

Regular routine. Many of my clients initially suggest planning a big, faraway event, such as a vacation for next December. However, positive, routine activities sustain a positive mood more than one-time, big events. Examples of routine activities include a regular date with a friend or a weekly exercise class. A good routine is like a good structure that maintains a good mood.

The activities Suzanne and her therapist picked could become part of her routine.

YOUR TURN! Develop Mood-Boosting Activities for Anna

Anna recently graduated from a community college program and has been living at home with her parents for the past six months while she looks for work. She is increasingly depressed. She completed a Daily Activities Schedule, which she reviewed with her therapist, who wanted to add activities that would increase pleasure or a sense of mastery or competence.

Anna noticed that her lowest mood is around 5:00 p.m. She is alone in the house, and her parents do not get home for another two hours. She spends the time surfing the web and ruminating. Her therapist tells her to stop ruminating and that surfing the web is not helping her. Anna used to like running, but she has not run for over a year. Her therapist suggests that Anna go back to running, starting with three times a week for an hour. Anna likes the idea. Together they decide that Anna will run Monday, Wednesday, and Friday for an hour at 5:00 p.m.

Now try the following exercise:

- Evaluate her therapist’s interventions in relation to the Guidelines for an Effective Activity Plan, and complete the following table. You can see my answers in the appendix.

| Suggested Activity | Developed Collaboratively | Specific and Concrete | Doable | Naturally Reinforcing | Regular Routine |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Run three times a week for an hour |

- After you assess the current plan, design a more effective one.

Monitor Your Client’s Mood Before and After Activities

If you ask your clients who are depressed if they will enjoy an activity, they will probably say no. Clients who are depressed don’t enjoy activities as much as they used to. However, clients tend to enjoy activities more than they think they will. Often, starting the activity is the hardest part. Rating moods before and after a pleasurable activity provides your client with important data on how adding mood-boosting activities to her life affects her moods. I usually ask clients to complete the Predict Your Mood worksheet, shown below. (You can download a blank copy at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.)

After clients try an activity, if their mood ratings improved, I ask what they learned. I want my clients to see that even though they believe that they will not enjoy an activity, their predictions are not necessarily accurate.

Let’s see how Suzanne completed the Predict Your Mood worksheet for two of the activities she was going to try and how her therapist used the worksheet.

| Predict Your Mood | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date and Activity | How much will I enjoy this activity?

(rate from 1–10; 1 = not at all; 10 = a lot) |

Mood Before Activity

(rate from 1–10; 1 = very happy; 10 = very depressed) |

How much did I enjoy this activity?

(rate from 1–10; 1 = not at all; 10 = a lot) |

Mood After Activity

(rate from 1–10; 1 = very happy; 10 = very depressed) |

|

Monday: Listened to music in the car |

3 |

7 |

5 |

5 |

|

Called friend, Rita |

3 |

7 |

6–7 |

4 |

Therapist: Looks like you did a great job of completing the Predict Your Mood worksheet. When you look at your responses, what do you notice?

Suzanne: Well, for one thing, in both cases my mood went up.

Therapist: Could you tell me more about that?

The therapist wants to expand and consolidate Suzanne’s awareness of the activity/mood relationship. When her therapist asks for details, Suzanne remembers the experience and it becomes more salient.

Suzanne: Well, I actually enjoyed listening to music. I chose some really upbeat old songs that I like. I think it distracted me from my bad morning.

Therapist: So listening to music was a good idea. What about talking to Rita?

Suzanne: That was also more enjoyable than I expected. We had a really good talk and caught up. She told me she missed me, and all my friends have been asking about me.

Her therapist uses a summary statement to consolidate the experience.

Therapist: I hear Rita missed you, and your other friends also miss you. Hmm (therapist gently smiles). Let’s look at the accuracy of your predictions. What did you initially predict? (They look at the Predict Your Mood worksheet.)

Notice how Suzanne’s therapist is not giving Suzanne the answers but is asking her for the information and letting her draw her own conclusions.

Suzanne: I predicted that I would not enjoy listening to music and calling Rita very much. I gave both a 3.

Therapist: And what actually happened?

Suzanne: (laughing a bit) Well, I actually enjoyed listening to music quite a bit; I gave it a 5. And I enjoyed talking to Rita way more than I expected; I gave it a 6 to 7—it was great to catch up.

Therapist: And what does that say about your predictions?

Suzanne: I guess I was wrong.

Overcoming Roadblocks: Your Client Did Not Try the Planned Activity

Despite your best efforts, your client will not always do the agreed-upon activities. First, ask your client what got in the way. Sometimes it is a simple answer. Next, ask what went though her mind when she thought of doing the activity. Did she think it was too hard? Did she think it would not help, or did she have other thoughts? I go back to the fundamental principle: Follow your mood-boosting plan rather than your depressed feelings. Remember, for depression, activity is like medicine. There is some evidence that clients who make a public commitment to doing an activity are more likely to follow through (Locke & Latham, 2002). If my client has supportive family members or friends, I encourage her to share her plans.

I then problem solve how my client could do the activity the next week, or modify the activity so that it is more doable. I make sure I remain encouraging and optimistic and convey my belief that treatment will work.

The first week, Suzanne listened to music every day on the way to and from work. However, at her next appointment, she told her therapist that she had stopped listening to music, that this past week she was just “too down.” Her therapist reviewed what Suzanne had learned from her Predict Your Mood worksheet. She decided to try again. Suzanne laughed and said she would have to listen to music “even with her depressed hat on.” Her therapist thought this was a great image, and used it often in therapy.

What If I Have Only a Few Sessions?

The research on behavioral activation has generally evaluated a protocol that involves sixteen weeks of treatment, and often two sessions a week for the first eight weeks (see, for example, Dimidjian et al., 2006). However, many therapists see clients for only a few sessions. If I have only a couple of sessions, I start with exploring what my client is no longer doing that she used to enjoy. I then explain the activity/mood relationship. Either in the first or second session, we work together to identify specific pleasurable activities she could start doing. I make sure the activities make sense given my client’s current level of activity. I try to target a period of the day when her mood is particularly low. If possible, I encourage social contact, as there is such strong evidence that it is a mood booster.

Preventing Relapse

To maintain a positive mood, your client needs to have good routines. What is involved in a good routine is different for every person, but it generally includes a structure to the day, socializing, some exercise, activities that are meaningful and connected to your client’s values, and some fun. I use the analogy of creating a strong structure for a building. If the supporting beams are rotten and weak, even if you have good drywall and a beautiful paint color, you will have an unstable house.

I teach my clients that after therapy ends, if they start to get depressed again or are going through a stressful time, they should examine their daily routine. I encourage them to notice their worst times of the day and think about how they can make those times better. I also encourage them to try adding even small mood-boosting activities throughout the day.

I also use activity scheduling to prevent depression with clients who are going through a particularly difficult time. If you have ever gone through a difficult time, I am sure people have told you to “take care of yourself.” This is good advice, but very general. I examine pleasurable activities my client has stopped doing because of the stress and see if we can add them back into her life, or add other activities that she enjoys. Together we make a specific plan that is doable and can be part of my client’s routine.

Agenda Item #5: Graded Task Assignments

Graded task assignments are used primarily when your client is avoiding important tasks that feel overwhelming. It is often a component of activity scheduling, problem solving, and treating procrastination.

Graded task assignments involve looking at a whole activity and breaking it down into smaller pieces, or chunks. These smaller chunks feel doable in a way that the whole task does not. Your client starts with completing the first chunk and progresses to additional chunks. It can be helpful to limit the amount of time a client spends on each task to make it feel more manageable. By breaking tasks down into specific chunks, your client can feel she is progressing as she completes each task. It can also be helpful to set a specific time when the tasks will be done.

For graded task assignments to be effective, the tasks have to be very specific and concrete behaviors. For example, if a client is procrastinating over filing his taxes, the first task might be spending twenty minutes reviewing the tax form, the second task might be spending half an hour gathering income statements, and the third task might be entering the income information he gathered on the tax form. You don’t need to set out all the steps, but it is helpful to specify the first few.

YOUR TURN! Use Graded Task Assignments

Below are examples of clients who are feeling overwhelmed. Their therapists want to use graded task assignments as an intervention. Look at their first task and decide if it is sufficiently specific and concrete, doable, and time-limited. I will do the first one; you do the next two. You can find my answers in the appendix.

- Cynthia’s boss asked her to be in charge of the site visit when members of the head office come to inspect their unit. She is feeling very overwhelmed. She and her therapist thought a good first task would be reorganizing the filing system to make it more systematic.

- Richard wanted to invite his whole family—about fifteen people—for Thanksgiving dinner. He is feeling very overwhelmed. His therapist and he thought that spending thirty minutes making a list of the food he wanted to cook would be a good first task.

- Alexandra wanted to find a part-time job. She is feeling very overwhelmed and tells her therapist she does not know where to start. She and her therapist thought that exploring her options for work would be a good first step.

Agenda Item #6: Increase Well-Being

The goal of behavioral activation is to decrease depression; however, most clients want to feel good, not just “less bad.” Positive psychology seeks to identify factors that lead to a happy, engaged, and meaningful life. The focus is on developing interventions that promote well-being rather than on alleviating depression (Seligman, Steen, Park, & Peterson, 2005). Most CBT therapists I know incorporate some of the following interventions into behavioral activation. Though less robust than the research demonstrating the effectiveness of behavioral activation, there is some evidence that these interventions may increase happiness (Duckworth, Steen, & Seligman, 2005; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009).

Activities That Increase Well-being

Socialize with friends and family. Social contact is the single factor most consistently related to happiness (Leung, Kier, Fung, Fung, & Sproule, 2013; Parks, Della Porta, Pierce, Zilca, & Lyubomirsky, 2012). Increasing positive social interaction is also one of the most effective interventions to increase happiness (Seligman et al., 2005).

Keep a journal of positive experiences. Write down one to three positive experiences a day. I ask my clients to take a moment to remember the experience fully and to see it occurring again in their mind’s eye.

Savor the moment. Make a conscious effort to enjoy a pleasant moment. It is helpful to focus on one’s senses to stay present. For example, if a client plans to take a walk, remind her to notice the flowers or the fresh air.

Express gratitude. Write one to three things to be grateful for every day. This is also called “counting one’s blessings.” I ask my client to take a moment to remember the blessing fully and to appreciate that it was in her life. Another form of expressing gratitude involves consciously telling, or writing to, others to say that you appreciate them or what they have done.

Practice acts of kindness. Consciously do a kind act you would not normally do. This may involve consciously acting in a kind manner to someone you would not normally be kind to, or doing an additional kind act to someone you would normally be kind to. Ask your client to notice the other person’s reaction to her acts of kindness. Often people smile, say thank you, or react in a positive manner, which in turn will contribute to your client’s feeling happy. It’s nice when someone smiles at you.

Think optimistically. Identify a potentially stressful upcoming event and then describe the best possible outcome. The more detailed the description, the more emotionally engaged your client, and the more positive her mood. Encourage your client to write the description and to form a detailed image in her mind of the positive outcome.

Homework: Practice CBT

Before continuing with the next chapter, take some time to try the homework.

Apply What You Learned to a Clinical Example

Complete the following exercises.

- Exercise 10.1: Raoul’s Cycle of Depression

- Exercise 10.2: Jamar Is Feeling Depressed

Apply What You Learned to Your Own Life

Therapists often talk about the importance of self-care. The exercises below are an opportunity for you to take some of the interventions from this chapter and, instead of using them with your clients, apply them to your own life—and in the process take care of yourself.

Homework Assignment #1 Add an Activity to Your Life That You Enjoy

Identify a low time in your day. Think of a small, doable activity you could add that you would enjoy or that provides a sense of competence. Use the Predict Your Mood worksheet, available at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

When I did this exercise, I realized my husband and I used to have a favorite TV series we watched Monday evenings. The series ended, and instead of watching TV together, we each did our own chores. Watching a favorite show with my husband versus doing chores—which do you think boosts my mood more? We picked a new TV series to watch.

Homework Assignment #2 Increase Your Happiness

Look over the list of interventions that increase happiness:

- Socialize with friends and family.

- Keep a journal of positive experiences.

- Savor the moment.

- Express gratitude.

- Practice acts of kindness.

- Think optimistically.

Pick one intervention and try it for a week. Do the following: (1) rate your overall mood before and after each time you practice the intervention; (2) rate your overall mood at the beginning of the week and at the end of the week.

Apply What You Learned to Your Therapy Practice

For this next assignment, pick a client whom you know well and who is depressed.

Homework Assignment #3 Complete the Understand Your Depression Worksheet with a Client

Using the information you already know about your client, complete the Understand Your Depression worksheet. How did this exercise help in understanding your client? Remember, you can download the worksheet at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

Homework Assignment #4 Try Behavioral Activation

Choose one of the following interventions, and try it with a client this coming week. You can find the worksheets on the website.

- Introduce the Daily Activities Schedule and complete the first day in session.

- With your client, pick an activity to add to his or her life that will promote pleasure or mastery. Use the Predict Your Mood worksheet to evaluate whether the activity had an effect on your client’s mood.

Let’s Review

Answer the questions under each agenda item.

Agenda Item #1: How does behavioral activation work?

- What is the main idea in behavioral activation?

Agenda Item #2: Help your clients understand their depression.

- How can you use the flower analogy to help your clients understand depression?

Agenda Item #3: Monitor your clients’ daily activities.

- What is the purpose of the Daily Activities Schedule?

Agenda Item #4: Plan activities that increase positive moods.

- What are two types of activities you might want your clients to add to their lives to help them feel better?

Agenda Item #5: Graded task assignments.

- What are graded task assignments?

Agenda Item #6: Increase well-being.

- What are two interventions that evidence indicates would increase well-being?