Chapter 11

Exposure Therapy—Clients Face Their Fears

In the previous chapter we covered behavioral activation. Did you have a chance to ask a client to monitor his or her daily activities? What about adding mood-boosting activities to a client’s life, or your own? Did you try graded task assignments to help a client break down an overwhelming task?

If you did not have a chance to do the homework, think of a mood-boosting activity you could add to your own life this week. Choose a small, doable activity. Schedule it into your week. Then try it, and notice the effect on your mood.

Set the Agenda

In this chapter we are going to learn how to use exposure therapy to help your clients face situations they have been avoiding.

- Agenda Item #1: What is exposure?

- Agenda Item #2: Prepare to do exposure.

- Agenda Item #3: Implement exposure.

- Agenda Item #4: Do postexposure debriefing.

- Agenda Item #5: Discuss relapse prevention.

Work the Agenda

As with all interventions, to use exposure effectively, it’s critical to begin with a clear understanding of how and why it works.

Agenda Item #1: What Is Exposure?

Exposure therapy is a treatment for anxiety based on gradual, planned, repeated exposure to what we fear, starting with easy situations and progressing to more difficult situations. It is based on the premise that the more we face our fears, the less anxious we become and the more we learn we can cope.

I want to start by telling you a story related to exposure from my own life. I am at Disneyland. My kids want to ride the really big roller coaster. We wait in line. I start to get anxious; the roller coaster looks pretty scary. I wonder, Are there lots of accidents? It occurs to me that if planes can crash, roller coasters can also crash. We get to the front of the line, I look at the roller coaster, and I have one of the most intense anxiety reactions of my entire life. I turn to my husband, with panic in my voice, and say, “I am absolutely not going on that thing!”

If I do not get on the roller coaster, what will happen to my fear? Next time, will I be more or less likely to go on a roller coaster? How will I feel about my ability to cope with roller coasters? How will I feel about my ability to cope with scary rides generally?

I am embarrassed to say, I turned around, made my way back through the long line, and did not go on a roller coaster for many years. If I wanted to get over my fear of roller coasters, what would you suggest? Here is my plan: Start with a really small roller coaster, and ride it a few times until I am comfortable. Next, try a slightly larger roller coaster. Once I am comfortable with this larger roller coaster, try an even bigger one. Basically, my plan for overcoming my roller coaster anxiety is exposure therapy.

Exposure therapy involves identifying the feared object or situation your client is avoiding and making a plan to face the fear. Your client starts exposure with objects or situations that elicit little fear and stays in the situation until either habituation occurs or he learns that he can cope with the situation. Your client then progressively faces situations that elicit more fear.

The Theory Behind Exposure

There are basically two theoretical models that explain exposure: habituation (Foa & Kozak, 1986) and exposure as a behavioral experiment (Clark & Beck, 2010; Craske, Treanor, Conway, Zbozinek, & Vervliet, 2014). My own sense is that both models are accurate and reinforce each other.

Habituation is based on the observation that when an anxiety-provoking stimulus is consistently paired with a neutral consequence, the fear response eventually extinguishes. Let’s look at my roller coaster example. The roller coaster is the anxiety-provoking stimulus. I think about riding a roller coaster and I get anxious. If I frequently ride a roller coaster and consistently nothing bad happens, riding the roller coaster becomes paired with a neutral consequence (nothing bad happening). If I ride often enough, I will habituate to the roller coaster and no longer be afraid. In our daily lives, exposure occurs naturally, all the time. Can you remember a situation where you were initially anxious, but as you got used to the situation, your anxiety diminished or disappeared? Maybe it was your first night in a new house, driving on the highway, or jumping off a diving board? By staying in the situation until you were no longer afraid, you were naturally doing exposure therapy.

Exposure can also be understood as a behavioral experiment that tests your client’s negative fear predictions (Clark & Beck, 2010; Craske et al., 2014). If you remember, anxiety is about expecting bad things to happen. Anxiety is fueled by your client’s overestimation of the danger of a situation and an underestimation of his ability to cope with both the situation and his feelings of anxiety. Clients often predict that something awful will happen or that their anxiety will become intolerable. For example, I believe that if I go on a roller coaster, there is a good chance that it will fall off the rails (this is an exaggerated belief in the danger of roller coasters). I also believe that I will become so anxious that I will be unable to stop screaming (this is an exaggerated belief in my inability to cope).

The exposure task is an experiment that tests the accuracy of your client’s negative predictions. By facing his fears, your client learns that the situation is not dangerous and that he can cope with both the situation and his feelings of anxiety. Your client will also learn that when feared situations are faced, over time, anxiety diminishes. By the way, I did go on a roller coaster recently; it did not crash, I did scream, and by the end of the ride I actually enjoyed it!

How Avoiding Maintains Fears

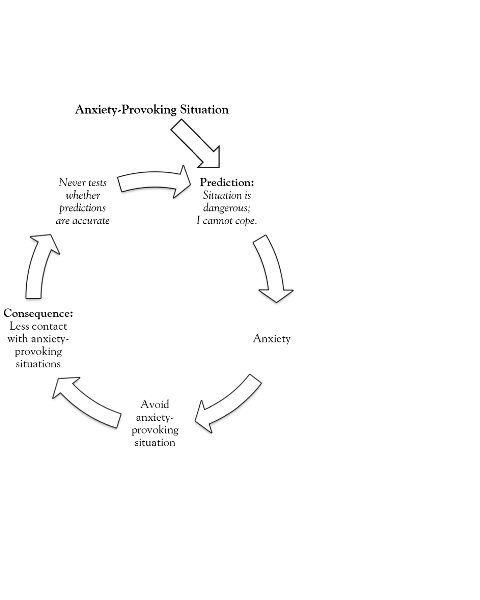

The key treatment component in exposure is to stop avoiding and to repeatedly confront your fears until you are no longer afraid. When we avoid situations, initially our anxiety decreases as we leave the feared situation. However, in the long term our anxiety increases because when we avoid we never learn that the situation is not dangerous and that we can cope. Over time, the number of situations we fear expands. We are caught in a self-fulfilling cycle. Take a look at Figure 11.1, the Cycle of Avoidance; you can see how avoiding leads to more avoiding and more anxiety and becomes a vicious cycle.

Can exposure therapy help Suzanne? At this point in therapy, Suzanne is doing better. She has been listening to music on the way to work and arriving in a better mood. She has also started socializing again with her old friends. As her mood has lifted, her relationship with her husband has improved and her mornings with the children have become less difficult. So generally things at home are going better. However, she still dislikes her new school and hardly interacts with the other teachers. Let’s see if exposure therapy can help her.

First let’s check if the cycle of avoidance applies to Suzanne. Situations that involve interacting with other teachers have become increasingly anxiety provoking for Suzanne. She believes that the other teachers do not want to be her friend and that even if she tried they would not like her (negative predictions). She is coping by avoiding almost all social contact. Since she avoids social contact, she never gets to check whether her negative predictions are accurate. In addition, if Suzanne is avoiding the other teachers, how do you think they react to her? Most likely they leave her alone, which reinforces her thought that they are unfriendly. Suzanne is caught in a vicious cycle.

Role of safety behaviors. Anxiety is maintained not only by avoidance, but also by what are called safety behaviors; I think of them as “fake” safety behaviors. Fake safety behaviors increase how safe you feel; they do not actually decrease the danger of the situation. Real safety behaviors, such as wearing a seat belt or looking both ways before crossing the street, do in fact increase your safety. For example, if I was only willing to get on a roller coaster with my daughter, having my daughter with me in the roller coaster is a fake safety behavior—if the roller coaster crashes, will it help if my daughter is with me? The problem with safety behaviors is as long as you use them, you never learn that you can cope without them.

The best way I know to explain safety behaviors is to tell you one of my favorite jokes. Harry is walking along the street, when he sees his old friend George. George is shaking his head from side to side saying, “shush, shush.” Harry goes up to George and says, “George, great to see you, but why are you saying, ‘shush, shush’?” George pauses. “I am keeping the zebras away.” Harry is a bit stunned. “But George, there are no zebras in America!” George smiles and says, “See, it works!” So, why have I told you this silly joke? Saying “shush, shush” is George’s safety behavior. Because he always says, “shush, shush,” he never learns that if he stops, there still will be no zebras in America.

It can take a while to learn to recognize safety behaviors. They generally fall into four categories (Abramowitz, Deacon, & Whiteside, 2011):

- Avoidance. Never putting your hand up in class to avoid sounding stupid; avoiding elevators because you fear they will fall.

- Checking, reassurance seeking, and rehearsal. Repeatedly checking if the door is locked; spending hours searching the Internet for information on every small ache and pain; mentally rehearsing what you say in casual conversations to be sure you do not look silly.

- Compulsive rituals. Washing your hands for half an hour after you go to the bathroom; needing to check twelve times that the windows are closed before you go to bed.

- Safety signals (objects you carry or have near you to be sure you are safe, even though the chances of needing them are slight or they could not really help). Having another person or an animal with you; making sure your cell phone is in your pocket with your finger on the emergency button in case you need to call for assistance.

The problem with safety behaviors is that they interfere with everyday functioning, and some safety behaviors actually make things worse. For example, a client is worried about germs and washes his hands for half an hour every time he goes to the washroom. This interferes with his ability to get his work and other tasks done, and, if excessive, can cause irritation and skin problems. A client with social anxiety is worried that she looks messy and awkward. While talking to a friend she constantly checks her hair. The constant checking makes her hair look messy, annoys and distracts her friend, and makes the client look awkward.

During exposure therapy, clients give up their safety behaviors in a planned, systematic manner so they can see that it is possible to cope without them.

Identify your clients’ safety behaviors. Sometimes when clients describe their anxiety, they include their safety behaviors. For example, when a client of mine described her fear of flying, she mentioned that she always has two or three glasses of wine before getting on the plane, to numb the anxiety. The wine is her safety behavior; she believes she needs it to tolerate the anxiety of flying.

You can also ask your clients directly about their safety behaviors. Next time one of your clients is describing her anxiety, try using Questions to Assess Your Client’s Safety Behaviors, available as a handout at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

- Are there things or situations you avoid because of your anxiety?

- Are there things you do to make yourself feel safe, or to be prepared in case of danger, such as carrying things or being with certain people?

- Is there anything you do to make yourself feel comfortable in situations where you feel anxious?

YOUR TURN! Identify Suzanne’s Safety Behaviors

See if you can help Suzanne identify her safety behaviors.

- Therapist: We’ve been talking about how anxious you feel around the other teachers at work, and generally how hard it’s been for you to make friends. I am wondering if there are things you do to make yourself feel more comfortable when you are with them.

- Suzanne: Well, I guess I have just been trying to avoid everyone as much as possible.

Look at three possible responses below and pick the one that will help Suzanne identify her safety behaviors.

- What are some of your thoughts when you feel anxious?

- Is there anything you do to make yourself feel more comfortable in situations where you have to interact with the other teachers?

- What are some of the worst situations for you, when you feel the most anxious?

Response #2 is the best response to help Suzanne identify her safety behaviors. Response #1 would be a good response if you wanted to explore her thoughts, but that is not the task at the moment. Response #3 would be a good question if you were starting to develop a hierarchy of situations, but not for identifying safety behaviors.

- Therapist: Is there anything you do to make yourself feel more comfortable in situations where you have to interact with the other teachers?

- Suzanne: If I really have to interact with them I try very hard to say something smart or funny. I will often rehearse a comment in my mind before saying it.

- Therapist: Anything else that you do to feel comfortable?

- Suzanne: Well, I usually wait until someone asks me a question before speaking. That way I don’t have to talk as much.

Suzanne identified two safety behaviors. The first is to rehearse in her mind what she will say before speaking. Do you think this will make her more or less fluent as a speaker? More or less anxious? The second safety behavior is waiting to talk until someone asks her a question. Is that likely to make her more or less engaged in the conversation?

One of the difficulties with safety behaviors is that there can be a fine line between coping and safety behaviors. For example, before cutting a piece of wood it is good practice to double check your measurements; however, checking six times becomes a safety behavior. Some safety behaviors are benign. For example, if my daughter is happy to come with me on roller coasters, and I will only go on a roller coaster if she is with me, this is a benign safety behavior. The assessment issue is whether the behavior interferes with your client’s functioning or causes her to avoid a situation that is not dangerous in reality.

Is Exposure Effective?

The answer is yes; in fact, exposure therapy is considered the most effective treatment we have for fear and anxiety disorders (Clark & Beck, 2010). Exposure has been used effectively for a variety of anxiety-related disorders, including panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), social anxiety disorder, PTSD, health anxiety, and specific phobias (Abramowitz et al., 2011; Clark & Beck, 2010). Despite its effectiveness, exposure therapy does not work 100 percent of the time. Some clients do not respond, and for some clients, after successful treatment, fears return. Researchers are exploring factors that predict who will respond and how to make exposure more effective.

Overview of Exposure Therapy

There are three types of exposure: in vivo, virtual, and imaginal. In vivo exposure involves exposure to what you actually fear. For example, if you fear needles, exposure tasks would involve an actual needle. Virtual exposure involves using the Internet, or another medium, to simulate the experience you fear. Often exposure to fear of flying relies on virtual exposure. Imaginal exposure is when your client uses his imagination to experience the situation. It is used primarily when in vivo or virtual exposure is not feasible. Trauma work usually relies on imaginal exposure to help clients face their trauma memories.

A word of caution: if your clients have poor impulse control, difficulty controlling their substance use, or suicidal ideation or urges, or if they engage in self-injurious behavior when under stress, it is generally not recommended to use exposure until they are stabilized (Taylor, 2006).

Exposure therapy generally occurs in three phases: preparing to do exposure, implementing exposure, and debriefing after exposure.

Agenda Item #2: Prepare to Do Exposure

Before you actually implement exposure, you want to prepare your client by going through the following steps:

- Identify the fear your client wants to address.

- Help your client understand how avoiding maintains his fears.

- Explain exposure.

- Develop a hierarchy of feared objects or situations.

Identify the Fear Your Client Wants to Address

You can use exposure in almost any situation where your client copes by avoiding. Suzanne was socially anxious, and in particular she was anxious about interacting with other teachers and colleagues at her new school. Below is a list of other types of fears you could treat with exposure. Take a moment to think of your clients and whether any of their fears fit into these categories.

- Fear of living creatures: Clients may fear dogs, insects, or human beings who remind them of an individual who hurt them.

- Fear of inanimate objects: Many clients fear germs, toilet seats, blood, or needles.

- Fear of specific situations: Clients may fear going to the dentist, public speaking, all kinds of social situations, and places that remind them of where they were hurt.

- Fear of specific thoughts, memories, or images: Clients with PTSD fear remembering the trauma; clients with OCD have specific thoughts that they try to avoid.

- Fear of specific physiological reactions: Clients can fear the sensation of having to cry, the physical symptoms related to going to the bathroom, or vomiting. Individuals with panic disorder fear the physical symptoms of anxiety.

Avoiding Is Not the Solution

Exposure is hard work. Unless clients understand the negative consequences of avoiding, they will not be motivated to engage in exposure. Many clients are so used to avoiding that they minimize the impact on their lives. I find the following questions helpful:

- How is avoiding a problem for you?

- If you were not avoiding this situation, how would your life be different? What would you be doing differently?

- Why is it important to you to stop avoiding?

When Suzanne’s therapist explored the consequences of avoiding social contact with the other teachers, Suzanne realized that she was lonely and felt isolated.

You can also increase motivation to engage in exposure tasks by linking cessation of avoiding to your client’s values. An important value for Suzanne is being friendly and having good relationships with other people. When Suzanne saw the connection between interacting with the other teachers and acting on her values, her motivation to stop avoiding social contact at school increased. Especially if clients are hesitant to engage in exposure, I examine how the exposure task is related to values that are important to them.

Explain Exposure

Exposure involves asking clients to do what they fear most. They need to trust you. I tell my clients that I will not ask them to do anything they do not want to do. I fully explain exposure and communicate my optimism. I often say, “This will initially be hard, but I think you will be glad you did it.”

I model a matter-of-fact attitude toward anxiety: anxiety is unpleasant but not dangerous. I let my clients know that anxiety will decrease as they avoid less and face their fears. I cannot promise to eliminate anxiety, but I can help them learn to cope with their anxiety. Below is how I generally explain exposure to my clients, of course, tailoring the explanation to each client. You can find Explain Exposure to Your Clients at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

We have been talking about how you avoid situations that make you anxious. We have also talked about how avoiding these situations has not helped and has actually caused you some difficulties. We have also talked about how being able to do the activity you have been avoiding is related to some very important values for you. (Only say this if you have been able to make the link to your client’s values.)

I think exposure therapy would be a very helpful treatment for you. Exposure therapy involves facing your fears. We will make a list of the situations that make you anxious, starting with situations that are fairly easy and going up to situations that are hard for you. We will start with the easiest and see if together we can help you learn to cope with the situation.

Once you have learned to cope with the easiest situation, we will progress to more difficult ones. We will work together and go at whatever pace works for you. How does that sound to you? (I pause to check if my client has any questions.) As you face your fears, you will learn not to be afraid.

I want to talk a bit about anxiety. You will feel some anxiety as we do the exposure tasks. But that’s okay; you need to feel some anxiety for exposure to be effective. We’ll go slowly. Also, the more we face what makes us anxious, the less anxious we feel. This means that the more you do the exposure tasks, the less anxious you will feel and the more you will learn to manage your anxiety.

YOUR TURN! Practice in Your Imagination: Explain Exposure Therapy

I would like you to imagine explaining exposure therapy to a client. Before you start, rate from 1 to 10 how comfortable you feel explaining exposure therapy. At the end of the exercise rate your level of comfort again to see if it changed. Now, let’s start this exercise.

Chose a client who you think would benefit from using exposure therapy. Try to get a picture of him or her in your mind. Now, imagine yourself in your office with your client. See your office; notice the sounds and smells in the room. Imagine that you want to explain exposure therapy. Read over the words I suggested while imagining yourself saying them. You can also use your own phrases. Really hear and feel yourself explaining exposure therapy. Imagine explaining exposure therapy two more times with the same client. Each time, imagine that your client responds positively.

Develop a Fear Hierarchy

A fear hierarchy is a list of situations that are increasingly anxiety provoking for your client. Fear hierarchies usually include objects or situations that are either increasingly similar in some way to the feared stimulus or involve physically approaching the feared stimulus. For example, if a client is afraid of spiders, a hierarchy of similar stimuli might include looking at a picture of a spider, touching a plastic spider, looking at a real spider, and finally touching a real spider. If a client was avoiding a street where she had been assaulted, a hierarchy based on physically approaching the feared stimulus might start with standing four blocks away, progressing to standing three blocks away, then two blocks away, and eventually standing on the street where the assault occurred.

I ask clients to give me examples of situations they find fairly easy, moderately hard, and very difficult. Here is Suzanne’s list of anxiety-provoking situations related to engaging in more social situations at school. Her therapist asked her to list three situations for each level of difficulty.

Fairly easy:

- Saying hello to other teachers I pass in the hall when I arrive at school

- Saying hello to another teacher on the way to recess

- Saying hello to the teacher next to me at assembly

Moderately hard:

- Eating in the lunch room and sitting down at a table with the other teachers

- Starting a conversation with the teacher next to me at assembly

- Asking for help with a school-related task, for example how to use the copier or where a resource is located

Very difficult:

- Asking another teacher to have lunch with me

- Making a comment at a staff meeting

- Volunteering to participate in the school play and letting the other teachers know that I have experience

When creating fear hierarchies, clients rate the difficulty of the tasks and their anxiety using subjective units of distress, or SUDS. A SUDS of 100 is the most anxious your client has ever been, and a 0 is not at all anxious. Using SUDS ratings helps clients keep track of their level of anxiety. You can download an example of a fear hierarchy that I used with a client who was afraid to go into a subway car after an accident. (See Sean’s Fear Hierarchy at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.)

Agenda Item #3: Implement Exposure

You are now ready to start doing exposure. This phase involves developing effective exposure tasks, identifying your client’s negative predictions, and actually doing exposure.

Develop Effective Exposure Tasks

Exposure tasks should be sufficiently easy to ensure success, but sufficiently difficult that your client learns that exposure works. I usually start with a task that has a SUDS rating of around 30 to 40.

There are three criteria for good exposure tasks:

- The task is sufficiently specific and concrete that it is clear to your client what he will do as well as when and where he will do the task, and he will be able to measure whether he was successful.

- The task specifies an action your client will do, and not how he will feel.

- The task is under your client’s control.

Let’s look at a couple of tasks and see if they meet these criteria.

| Task | Specific and Concrete? | Action the Client Can Do? | In Client’s Control? | Conclusion: Is This an Effective Task? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Impress my boss with a good question |

No, not clear what he will do, when or where |

No, not clear what he will do |

No, can’t control whether your boss will be impressed |

No BETTER TASK: Ask one question at staff meeting. |

|

Walk in the area where I was assaulted |

Not sufficiently specific. Where will client walk? For how long? |

Yes, client can walk |

Yes, in client’s control |

No BETTER TASK: Walk for fifteen minutes, three blocks from where the assault took place. |

YOUR TURN! Develop Effective Exposure Tasks

Look at the two exposure tasks below and decide whether they are (1) sufficiently specific, (2) an action that the client can do, and (3) under the client’s control. If you do not think they are good tasks, develop a better task. You can find my answers in the appendix.

| Task | Specific and Concrete? | Action the Client Can Do? | In Client’s Control? | Conclusion: Is This an Effective Task? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stand in front of the elevator in my building for 5 minutes every day |

||||

|

Look at photos on the Internet of cars similar to the one that hit me |

First Exposure Task

If possible, either conduct the first exposure task with your client in your office or go with your client to the situation he fears; that way, you can be sure that your client understands the process and you are there for support. In my many years of doing exposure, I have played with plastic spiders and plastic knives; stood in front of elevators, subways, and streetcars; and looked at photos of cars, knives, and vomit. The Internet is fabulous for exposure therapy—you can find photos and videos of almost anything!

For her first exposure task, Suzanne suggested starting with saying hello to teachers she passed in the hall on the way to class in the morning. Her SUDS rating was a 40. The task is specific and involves an action that Suzanne will do. However, her therapist thought the task was not sufficiently specific, and it would be hard to measure whether she was successful. They decided she would say hello to at least three teachers, five days a week in the morning on the way to class.

Move Up the Hierarchy

Once a client has accomplished the first task on the hierarchy, we develop the next step collaboratively. I ask my client what would be a good next task. Generally I aim for tasks with SUDS of 40 or 50, though sometimes clients want to try a task with a higher SUDS rating that they feel is doable. Traditionally, you would not move up the hierarchy until your client’s anxiety in response to the present task had decreased by 50 percent. However, recent research (Craske et al., 2014) suggests that this may not be necessary. I usually move up the hierarchy when my client indicates he is ready and can manage the next task.

Make Exposure Effective

There are some specific factors that can help make exposure tasks more effective.

Tasks should be frequent and prolonged. Do you think it would be more effective for me to ride a roller coaster three times a day for five days in a row or once a week for fifteen weeks? Probably three times a day for five days. What about a two-minute ride or a fifteen-minute ride? It is important to repeat the exposure task a number of times to consolidate the learning experience.

Tasks should be varied and done in multiple contexts. Do you think I should ride one roller coaster at one amusement park over and over, or a variety of roller coasters in a variety of amusement parks? Various roller coasters in various amusement parks will be more effective.

Exposure should be mindful. Clients often distract themselves during exposure to avoid really facing their fears. When a client is mindful, he is present in the moment (Teasdale, Williams, & Segal, 2014). Many of my clients say mantras, space out, close their eyes, or pretend they are not there. I use various grounding techniques to help clients stay present (Dobson & Josefowitz, 2015). For example, I watch my client’s eyes to make sure he is looking at the anxiety-provoking stimuli, and during exposure I ask him to label what he sees, to feel the ground beneath his feet, and to notice any sounds. I also ask my client to notice and label his feelings or thoughts without needing to change the thoughts or the physical sensations.

Safety behaviors should be eliminated gradually over the course of exposure therapy. Eliminating safety behaviors is part of the fear hierarchy (Rachman, Shafran, Radomsky, & Zysk, 2011). For example, a client kept a clonazepam in his pants pocket as a safety signal whenever he had to fly. As he became more comfortable with flying, he moved the clonazepam to a bag at his feet, then to a bag in the overhead compartment, and finally, he flew without the clonazepam. For my roller coaster exposure, I would start with riding roller coasters with my daughter (being with my daughter is my safety behavior) and then go on them by myself.

Between-session exposure tasks should be assigned. It may not be possible to conduct the exposure tasks with your client, as the anxiety-provoking stimuli may not be easily accessible. This occurred in Suzanne’s case, where the exposure task involved behavior that would take place at school. A lot of exposure work is done between sessions, as homework. If we completed an exposure task during therapy, my client’s homework is usually to do the same task on his own. This enables the client to consolidate the work we did together.

Identify Your Client’s Negative Predictions

Remember that you can think of exposure as a behavioral experiment. This means you ask your client to predict what will happen during the exposure task. The exposure task is a test to see if the prediction was accurate (Craske et al., 2014). Remember, in chapter 6 we defined anxiety as expecting bad things to happen and we used the following equation to understand anxiety.

Figure 11.2. Understand anxiety.

Figure 11.2. Understand anxiety.

I want clients to predict what will occur and how they will react so that we can examine the accuracy of their predictions and change the anxiety equation.

Clients often have “realistic” predictions and “worst-case” predictions. I ask for worst-case predictions because I want to test whether the belief that is driving the anxiety is accurate. I look for two types of predictions: first, what is my client’s worst fear, or what is he most worried will occur? I then ask my client to rate the likelihood of his prediction occurring. Second, I ask my client to predict his worst fear about how he will react—about how he will feel, about the symptoms of these feelings, and about what he will do. I then ask him to rate the likelihood of this occurring. It is important that the predictions are sufficiently concrete that your client can judge the accuracy of his predictions. Often a client’s prediction involves how he or other people will feel. Try to specify the behaviors your client predicts will happen as a consequence of the feelings; predictions that are behaviors are easier to assess than predictions that involve feelings. For example, if a client predicts he will be anxious, ask what he is afraid he will do because of his anxiety, or what symptoms he is afraid he will have. For example, is he afraid he will talk too quickly, or blush, or have a crushing feeling in his chest? If a client predicts that a friend will be bored, ask how he will know that the friend is bored.

Below are some examples of predictions.

| Exposure Task | What are you most worried will occur? (Likelihood 0–100%) | How am I most worried I will react? (Likelihood 0–100%) |

|---|---|---|

|

Stand in the subway station and watch a train |

Someone will throw himself on the track and get killed. (80% likely) |

I will be so anxious that I will lose control and throw myself on the track. (50% likely) |

|

Look at a drawing of a cockroach for 15 minutes |

I will find it too difficult to do. (50% likely) |

I will be so anxious that I will run out of the room screaming or faint. (40% likely) |

|

Ask a question in class |

The teacher will say it is a stupid question. (60% likely) |

I will freeze and stumble on my words. (95% likely) |

|

Ask a friend to go to the movies |

My friend will not want to go. (90% likely) |

If my friend says no, I will be quiet on the phone and stay home feeling depressed the rest of the day. (90% likely) If we do go out, I will have nothing to say and will be quiet the whole evening. (80% likely) |

Below are some questions to help your clients identify their predictions. You can download Questions to Identify Your Client’s Predictions During Exposure at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501.

I start with saying, “When you think of doing the exposure task,”

- What is your worst-case scenario?

- What is your worst fear about what will happen, including how other people will react?

- What is your worst fear about how you will feel, including your worst fear of the symptoms you will have?

- What is your worst fear about what you will do or how you will behave?

- What do you imagine will happen? Do you see it happening? (Clients often have images of what will occur during the exposure task.)

Suzanne’s therapist asked her what was the worst that could happen if she said hello to the teachers in the hall. Suzanne responded that she would be anxious and rated her anxiety a 5 out of 10. Her worst-case scenario was that she would say hello in a hesitant and awkward manner and her face would turn bright red. She rated the likelihood of being hesitant at 75 percent and turning bright red at 45 percent. Suzanne’s therapist then asked for her worst-case scenario of how she expected the other teachers to react. Suzanne responded that the other teachers will “ignore me and walk past me without saying anything.” She had a clear image of two teachers in particular smirking at her. Suzanne now has a concrete prediction that she can assess. Suzanne’s therapist wrote down her worst-case predictions and her likelihood ratings so that they had a record to refer back to.

In exposure therapy you do not verbally challenge your client’s predictions, no matter how farfetched they may seem. You write them down and use the exposure task as an experiment to test whether the prediction is accurate.

Agenda Item #4: Do Postexposure Debriefing

Once your client has completed the exposure task, you want to discuss what he learned.

Monitor Outcome of Exposure Tasks

It is helpful if your client can monitor, on a written worksheet, the outcome of his exposure task and his anxiety level. This provides data that can be used to challenge his predictions. I ask clients to monitor their anxiety every five minutes if the task involves staying in a situation for a prolonged period of time, or until their anxiety decreases. In Suzanne’s case, she recorded her anxiety at the beginning and the end of the task. Below is Suzanne’s monitoring worksheet.

| Task: Say hello to three teachers a day on the way to class in the morning. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Teachers Said Hello To | Anxiety (SUDS) | ||

| Start of Task | End of Task | ||

|

Monday |

3 |

40 |

40 |

|

Tuesday |

3 |

40 |

35 |

|

Wednesday |

4 |

30 |

25 |

|

Thursday |

5 |

20 |

10 |

|

Friday |

5 |

10 |

10 |

Complete the Postexposure Debriefing

The next step is to debrief or explore what your clients learned from the exposure task. I use the anxiety equation we looked at earlier as the conceptual model that guides my debriefing. You want to review:

- The accuracy of your client’s initial predictions

- The danger or difficulty of the situation

- Your client’s ability to cope with the task and with his anxiety

- What happens to anxiety with exposure

In debriefing, you are gathering evidence and looking for facts that will enable your client to evaluate the accuracy of his prediction. I usually use the Are My Predictions Accurate? worksheet, which you can download at http://www.newharbinger.com/38501. Let’s look at how Suzanne and her therapist completed the worksheet.

You will use the data you collected to debrief and assess whether your client’s predictions were accurate. I explore both my clients’ ability to stay in the anxiety-provoking situation and their ability to tolerate anxiety. Anxious clients often use their anxiety as a sign that they need to avoid the situation. I want my clients to learn that they don’t need to listen to their anxiety but rather can make decisions about how they want to behave. You also want to reinforce that anxiety will decrease with exposure.

Let’s look at how we might debrief with Suzanne. Notice how her therapist helps Suzanne reach her own conclusions and then reinforces the conclusions.

Was Suzanne’s prediction accurate in relation to the danger or difficulty of the situation?

Therapist: Do you remember what you predicted would occur if you went up to teachers and said hello?

Suzanne: Yes, I predicted that they would ignore me, and two teachers would smirk.

Therapist: And what occurred?

Suzanne: Almost all of them smiled and said hello back.

Therapist: Hmmm, what do you make of that?

The therapist is asking Suzanne to reach her own conclusions.

Suzanne: I guess my prediction was wrong; people were friendly.

Therapist: (smiling) Can you say that again?

The therapist is reinforcing Suzanne’s conclusions by asking Suzanne to repeat her conclusion.

Suzanne: (laughing slightly) People were friendly.

Therapist: I think that is a very important observation.

Was Suzanne able to cope with the task and her anxiety?

Therapist: When you started the task, on the first day, where was your anxiety?

Suzanne: It was at a 40.

Therapist: And were you still able to say hello to the other teachers and accomplish the task?

Suzanne: Yes, I was.

Therapist: The fact that you were able to say hello to teachers even though you were anxious, what does that tell you about needing to avoid if you are anxious?

Suzanne: I guess I can still do things, even if I am anxious. It seems that just because I am anxious, I don’t have to avoid.

YOUR TURN! Continue Debriefing with Suzanne

Try using what you’ve learned to help Suzanne understand the effects of exposure on her anxiety.

- Therapist: I’m curious what happened to your anxiety over the course of the week as you said hello to the other teachers.

- Suzanne: Well, it got easier and easier, and my anxiety went down.

Look at the three responses below. How could you help Suzanne reach her own conclusions about the effect of exposure on anxiety?

- I think that’s great. This is exactly what we would expect from exposure therapy. The more you do a task, the easier it will be and the less anxious you will be.

- Given that your anxiety went down, what did you learn about what happens to anxiety when you do exposure?

- What helped you confront the task?

Response #2 is the best response to help Suzanne reach her own conclusions. Response #1 would be a good response after Suzanne had reached her own conclusions in order to reinforce them. Response #3 would be a good question if you wanted to understand how Suzanne had motivated herself.

Consolidate What Your Client Learned

After you have debriefed the exposure task, you want to help your client consolidate what he learned. I use three approaches: developing a more accurate prediction, imaginal rehearsal, and review.

To develop a more accurate prediction, I refer to my client’s original prediction and then ask what would be a more accurate prediction, given what occurred during the exposure task. I encourage my client to write down his new prediction. Next I use imaginal rehearsal to review the outcome of the exposure task and the new prediction. In Suzanne’s case her new prediction was that the teachers would be friendly when she said hello. Her therapist asked her to create an image and see the various teachers smiling at her and saying hello. Her therapist then asked Suzanne to review this memory three times a day as part of her homework.

Agenda Item #5: Discuss Relapse Prevention

One of the difficulties with exposure treatment is that fears can return after treatment (Craske & Mystkowski, 2006). I explain to clients that exposure is similar to exercise. Even if you exercise every day and get into really good shape, you have to keep exercising or you will not stay in shape. Exposure is similar; you have to keep practicing for the benefits to last. At the end of therapy, I explain the principles of relapse prevention:

- Continue to face situations you previously avoided. Remember: anxiety is not a reason to avoid.

- The more you face your fears, the easier it becomes. Remember: anxiety is normal and exposure works.

Homework: Practice CBT

Before continuing with the next chapter, take some time to try the homework.

Apply What You Learned to a Clinical Example

Complete the following exercises.

- Exercise 11.1: Suzanne Avoids the Other Teachers

- Exercise 11.2: Maia Was Attacked

- Exercise 11.3: Aiden Uses a Knife Again

Apply What You Learned to Your Own Life

After you have completed the homework assignments below, pause and take a moment to think about what you learned about yourself. Then, think about the implications of your experience with these exercises for your therapy with clients.

Homework Assignment #1 Identify Your Own Safety Behaviors

Think of a situation in the past month where you were anxious. What did you do to make yourself more comfortable? For example, did you carry an object or be with a certain person? Did any of your strategies involve avoidance, checking, reassurance and rehearsal, compulsive rituals, or safety signals? What was the consequence of your safety behavior?

Homework Assignment #2 Develop a Fear Hierarchy

Try to think of any situations that you have been avoiding. It could be a social situation or a specific fear.

- Develop a fear hierarchy for your problem. Think of situations that are fairly easy, moderately hard, and very difficult.

- Choose a first task; make sure it is concrete, an action that you can perform, and in your control.

- Make a prediction of what will occur if you do the first task.

- Now, it is up to you to try the task.

Apply What You Learned to Your Therapy Practice

For this next assignment, think of a client whom you are currently working with and who suffers from anxiety.

Homework Assignment #3 Identify Your Client’s Safety Behaviors

Once you have chosen a client, complete the following steps.

- Ask one or two questions from the handout Questions to Assess Your Client’s Safety Behaviors.

- • Are there things or situations you avoid because of your anxiety?

- • Are there things you do to make yourself feel safe or to be prepared in case of danger, such as carry things or be with certain people?

- • Is there anything you do to make yourself feel comfortable in situations where you feel anxious?

- If your client is avoiding, ask how avoiding is a problem in his life.

- Once you have identified your client’s safety behavior, explain safety behaviors and explore the consequences of the client’s safety behavior.

Homework Assignment #4 Develop a Fear Hierarchy

Think of a client who is avoiding and who you think would benefit from facing his or her fears.

- Develop a fear hierarchy with this client. Identify situations that are fairly easy, moderately hard, and very difficult.

- Identify a first exposure task. Make sure it is concrete, an action your client will take, and under his or her control.

- Ask your client to predict what he or she thinks will occur.

- Steps 1 through 3 may be enough for your first experience with developing a hierarchy. However, if you feel you are ready, and it would be helpful to your client, ask your client to try this first task.

- Check whether your client’s predictions were accurate.

Let’s Review

Answer the questions under each agenda item.

Agenda Item #1: What is exposure?

- What is the central theory of exposure?

Agenda Item #2: Prepare to do exposure.

- What two things do you want to do before you start exposure?

Agenda Item #3: Implement exposure.

- What are three factors that make for an effective exposure task?

Agenda Item #4: Do postexposure debriefing.

- Why is it important to have a postexposure debriefing?

Agenda Item #5: Discuss relapse prevention.

- What are two important things to tell your clients about relapse prevention?

Figure 11.1. Cycle of avoidance.

Figure 11.1. Cycle of avoidance.