Douglas Stewart’s early life, as described in his autobiography Springtime in Taranaki (1977) and earlier volume The Seven Rivers (1966), was idyllic. It was the kind of childhood that has now all but vanished. He fished, built tree houses, went on excursions over hill and dale, swam in the rivers. He knew all the local people by name. He had dogs, cats, rabbits, guinea pigs, pet sparrows and even, for a short period, a leveret.

The second oldest of an Australian-born country lawyer and devoted, light-hearted mother who liked a laugh and a song, Doug was one of five children. They lived in the small town of Eltham in the province of Taranaki, on the western side of the North Island, close to Hawera and New Plymouth.

The volcano Mt Taranaki, which Doug knew by its now abandoned colonialist name Mt Egmont, rises magically above the plains. It is not part of a range but stands proudly alone. On a clear day on the road from New Plymouth to Eltham you can enjoy seeing Mt Ruapehu and his brother Tongariro away to the north: three snowy peaks – one close in, the other two at a distance – rising high above the green plains. In Māori legend the mountains are gods who once all lived together in the centre of Te-Ika-a-Māui (the fish of Māui, or the North Island) but fought over nearby Pihanga, the only mountain goddess among them. At the close of the battle Tongariro sent the loser Taranaki to stand all by himself near the coast, as far to the west as he could go. And stand there he does. In Stewart’s words, the majestic, breath-taking mountain ‘made the whole world miraculous’.1

For Eltham, the mountain is the one constant. So much has changed. In Stewart’s day the town was a thriving, close-knit community. There were two banks – the Bank of New Plymouth and the Bank of New South Wales. There was a draper, a butcher, a grocer, a dentist, a doctor, a pharmacist, a fine town hall and substantial courthouse, two practices of lawyers, two hotels, a newspaper office, a Presbyterian church, a Roman Catholic church and, just out of town, on the road back to Stratford, a park that contained exotic animals for entertainment on Sunday afternoons.

Today Eltham is a charming but melancholy example of true rural decline. On Bridge Street, the main shopping street since the town was founded, the majority of shopfronts are boarded up. Most of those that remain open sell second-hand clothes, collectibles and junk. There are no banks, no butcher, no grocer, no dentist, no pharmacy, newspaper office or legal practice. On a lower corner of the street spreads a large lurid-green franchised seed and garden merchant. This is the site that once held Chew Chong’s business. Chew Chong was the enterprising businessman who first created the pound of butter as a means to package and export the commodity to England, a move that ensured a good part of the nation’s wealth for over a century and for which, it could be argued, he should be celebrated rather than forgotten. Chew Chong was perhaps the father of the man Stewart remembered: ‘the humble nameless Chinese vegetable man who sold us crackers and skyrockets in season and, at all times, lettuces for threepence’.2

Next door to the old Chew Chong site is the courthouse, with its imposing entrance, Doric columns, ornate pediment and crenellations. It was officially opened by Prime Minister Sir Joseph Ward in 1908. It hints at the dashed hopes and failed ambitions of those fin-de-siècle townspeople. By the early 1950s it was very apparent that the town was not going to grow, and with improved technology and transport the courthouse was no longer needed: lawyers and criminals alike could make the journey to New Plymouth or Hawera or even further afield. The courthouse was closed and only a short time later converted into an imposing veterinary clinic. The building retains that function today.

Bridge Street, Eltham. The photograph was taken around 1913, the year Douglas Stewart was born in the Taranaki town. Frederick George Radcliffe photographer, ref. 1/2-006046-G, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

Unlike many small towns in New Zealand fallen prey to the wrecker’s ball, Eltham preserves many Victorian and early twentieth-century shopfronts and old buildings, and they are consciously preserved. With only a little dressing, Bridge Street has been used as a set for films and television drama. Perhaps as more and more young New Zealanders find it increasingly difficult to survive in our major cities, towns like Eltham will be not only revived but loved and treasured as they were in Stewart’s day.

So who were the people who lived in Eltham during Stewart’s boyhood? Māori, of course, although not to the extent his readers and listeners might have assumed given the prominence of Māori culture in much of his New Zealand-inspired poetry and work for radio and stage. In a possibly unintentionally tragic passage in Springtime in Taranaki he recalls: ‘Plump Maori ladies, with tattooed chins and bare feet, came and sold us kit-bags made of flax, and purple, earthy kumaras, and treat beyond all treats, beautiful fresh whitebait which they would have netted, I suppose, at the mouth of the Waingonoro near Hawera, where they lived. Often, lords of the land as they had once been, they would ask for old clothes in exchange for their wares.’3 There were Dalmatians and Austrians too, employed to dig ditches to drain swamp for farmland. It’s possible that some of these families called ‘Austrian’ were Croatian but misidentified because they were members of the Hapsburg Empire. A man with the Croatian surname Radisch (more likely Radich) was the fishmonger.

It was the more usual, bog-standard English, Irish and Scottish immigrant stock that closely surrounded Stewart as he grew up. His own family were of Scots extraction. His grandfather, Rev Alexander Stewart, was a Presbyterian minister. Having tried Dunedin for a short period, he went to live in Geelong and then Melbourne where he married the daughter of a wealthy landowner and raised his family. Rev Alexander was no ordinary minister. Ambitious, hardworking and clever, he rose to be Moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church in Australia.

There appears to have been some tension between Stewart’s father, another Alexander, and the minister. The cause of the quarrel is not known but it may perhaps have been about the academically gifted young Alexander studying medicine instead of entering the Church. At any rate, it resulted in Stewart’s father leaving Melbourne. When he arrived in Auckland, his knowledge of the classics meant he was able to obtain a position teaching Greek and Latin at King’s School, Remuera. Another position followed at a country school in the Hauraki Plains town of Waihi, which is where he met and married Mary FitzGerald. After their marriage the couple moved to Rawhiritoa, in Taranaki, where Alexander taught at the small local school and studied law at night. Soon after qualifying he and his young wife moved to nearby Eltham. He became a partner in a practice with two other lawyers, and stayed in the town for the rest of his life.

In Stewart’s account, his father was a contented man. He did not inherit his own father’s ambition, happy instead to practise law in a small country town. He kept limited hours, refused big criminal cases such as they were, and confined his business to conveyancing and minor offences. Stewart remembered his mother encouraging her husband to go back to work in the afternoon after lunch, when he would rather sit and read in the sun or adjourn to the golf course. The family house was in Meuli Street, which abuts the only hill in the district apart from the distant mountain. A photograph shows it complete with veranda and an iconic cabbage tree in the front yard.

They were wealthy enough to afford housemaids drawn from one local family, and a gardener. These days perhaps we would credit Alexander Stewart with advanced E.I. (emotional intelligence) and a healthy work-life balance. He had what he wanted – a beloved wife, a healthy family, a pretty house set in half an acre of gardens, a job he liked better than teaching, golf and plenty of books. He also had, at a time when car ownership was rare, a Buick, which conveyed the family to Opunake beach for long summer holidays.

In keeping with their middle-class position in the small society of Eltham, Douglas Stewart attended a private primary school from the time he was five until he was eight. This was presided over by a Miss Hooper, who was strict but firm, and ‘given to laughter’. After three years of her benign tutelage, Eltham Public School was a rude shock, particularly since the schoolmistress there was fond of the strap. By his own count, Miss Papps gave him some three hundred cuts in the first year. All of us educated before the 1980s have memories of the drawer in the teacher’s desk in which the regulation-issue strap was kept, and how ominous it was when the teacher removed it for use. Astonishing as it now seems, getting the strap was part of the quotidian existence.

Miss Papps can’t have been all bad, because she encouraged Stewart in his first attempts at writing. It was a story from the point of view of an old, rusted umbrella lying discarded in the washhouse, and he recalled that, basking in her praise, he thought he might become an author. It was an ambition that was to fade for a number of years.

Young New Zealanders of the twenty-first century are very aware of the historical tensions between Māori and Pākehā. Less do they know of the historical mutual antipathy between Catholic and Protestant factions. Children nationwide would call out to one another, depending on which side they were on:

Cattle dogs

Jump like frogs

Don’t eat meat on Fridays!

Or:

Catholic, Catholic ring the bell

While the Protestant goes to hell.4

As a boy, then, Stewart would have been aware of the divisions between Catholic and Protestant, between Māori and Pākehā, and also between the two nationalities absorbed into his family. Of all of the five subjects of this book, Stewart would have been the most familiar with not only the idea of Australia but the reality of it.

Most importantly, there was a real live emissary from West Island. Granny would come to stay – a kind, gentle woman who was in possession of a purse bulging with pennies and sixpences, and who welcomed the children who jumped into bed with her in the morning for a cuddle. In Stewart’s recall the family seem more demonstrative than many in this era when it was not uncommon for Pākehā children, and especially boys, to receive no physical affection at all.

Letters would have gone back and forth between Eltham and Melbourne, bringing family news of West Island. By far the greater source of Australian information on a national scale was the weekly Bulletin. Stewart’s father subscribed to it at a time when it was one of the most widely read magazines in Australasia. Published in various formats between 1889 and 2008, the Bulletin was an opinion-maker on politics, commerce, arts and literature.

Stewart, being an observant child and very fond of his father, would have learnt from an early age that the Bulletin was, for him, very close to a holy book. He would also have known that in Australia the magazine was fondly known as the Bushman’s Bible. In imitation of his father he would have studied it closely, from its now highly controversial masthead, Australia for the White Man, to its cartoons and funny stories and, most importantly, the ‘Red Page’, the Bulletin’s literary component. Poems, literary gossip and reviews in what looks to a modern eye like crowded typography filled its pages. Much of it would have made little sense to a small boy, even a literate small boy, in a small town in New Zealand, but it would have encouraged his already strong perception of Australia as a place of ideas and stories.

The enviable childhood went on. After the war, FitzGerald uncles and aunts came to settle in Eltham to be close to Stewart’s mother, who was the fulcrum of the family. The Meuli Street front parlour was used for the Glee Club – entertainment in the days before radio and television. The locals interested in music would gather around the piano to sing ‘surprisingly juvenile items’ – rounds like ‘Humpty Dumpty’, ‘Three Blind Mice’, ‘Ten Green Bottles’.5 Folk songs and Gaelic songs were also part of the repertoire. Stewart’s father would parade up and down singing, pretending to play the bagpipes. Stewart remembered not only the participants but also the quality of their voices: Harold Northover from the box factory, for example, with his ‘husky baritone’.

In his introduction to Springtime in Taranaki, long-time friend and literary agent Tim Curnow remarks on Stewart’s prodigious recall for names. It is perhaps one of the most extraordinary aspects of what is, apart from some standout passages of nature writing – which was Stewart’s true gift – a very ordinary account of an ordinary middle-class rural childhood. Aside from family, he recalled some 25 full names of tradespeople and professionals in the town

‘How innocent and merry and companionable were the pleasures of life in Eltham!’ Stewart remarked.6 There were the usual less innocent children’s pastimes and experiences, which he recalled with great humour and candour. He remembered playing games of ‘Rudey’ with a friend of his sister’s, ‘inspecting with great interest such differences as were to be detected between little boys and little girls; and then, since we knew nothing of the more enterprising games we might have attempted, decorating any crevices we could find in each other with ivy leaves. It was rather a charming game, now I come to think of it, and I am sorry we did not play it more often.’7 On holidays with family friends who were farmers, he and his mate shared quarters with farmhand Phil. This man was ‘blessed with the most enormous doodle every worn by mortal man. Really, he was like a stallion. As he invariably went to bed wearing only his singlet, we saw a good deal of this mighty object, swinging about and casting long shadows in the candlelight or gruesomely dangling in the dawn, and we never failed to be impressed by it.’8

The year Stewart turned 13 he was sent some 30 kilometres west to board at New Plymouth Boys’ High School, where he would remain for the next five years. The school sits high on the hill overlooking the small city of New Plymouth and with a panoramic view of the sea. It is a handsome institution, with buildings of the same vintage and style as those of other prestigious grammar schools in New Zealand such as Mount Albert Grammar in Auckland.

New Plymouth Boys’ is still a boarding school, though the original boarding house is long demolished. The senior housemaster occupies a gracious, late-nineteenth-century two-storey house at the memorial gate. The high white gate is itself impressive, a sombre monument to former pupils killed in World War I. Among the many old buildings still in use is a gymnasium with gabled roof and turret. There are new classrooms and facilities for the boarders, mature trees, music rooms and playing fields. One field occupies the top of a hill, and another called The Gully is exactly that, with high eastern and western terraces carved into the banks for spectators. Walking around the deserted grounds one Labour Weekend, I had the sense of a school well cared for and treasured by its community.

Stewart’s years at New Plymouth Boys’ seem to have been, in the main, happy ones. After being asked to write a poem for the school magazine he found not only that he could write poetry but that he loved it, and ‘so changed the universe’.9 This was a poem of around 30 lines, a dialogue between an angler and the stream he fished: evidence of his two life-long passions – fishing and poetry – taking hold. All students were given Smith’s Book of Verse, a standard text of the time, which contained carefully chosen extracts from the works of Shakespeare, Herrick, Milton, Wordsworth, Burns, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Browning and Tennyson. Stewart read it so often that he knew much of it off by heart.

Many of us are grateful to the one teacher during our high school years who saved our lives if we were having a difficult time, or who recognised where our strengths lay and so gave us direction. Stewart’s saviour was a Scottish master, Jas Leggat, his English teacher. Leggat arranged for him to join the New Plymouth Public Library, where he could read more poetry than the school offered. It was there that he discovered the more recent poets, the men (and they were all men) deemed to be influencing the next generation of bards: Yeats, Walter de la Mare, W.H. Davies, Edmund Blunden, Siegfried Sassoon, Richard Church, Humbert Wolfe and Rupert Brooke.

The reading inspired him and gave him further confidence. He sent a newly penned sonnet to the Taranaki News and was mortified when it was published in the Children’s Page. At school he made friends with the young Denis Glover, though doesn’t relate whether at this stage Glover had ambition to write. He remembered him as ‘a shrill, pink-faced boy … who was always my great rival in French and English’.10

So confident was he of his own abilities that at age 15 he started to send poems to the Bulletin. Later, under the auspices of Pat Lawlor, the Bulletin would have a New Zealand office situated in Wellington; at this time, however, the magazine was generated from Sydney. Stewart sent so many poems across the Tasman that he would later describe it as a bombardment. In the same year he began submitting to the Bulletin, the school asked him to write new words for the school song. He regarded this as a great honour. Many years later he would return to New Plymouth Boys’ High to rejuvenate these lyrics, removing from them the imperialist sensibility that had infused the first ones. New Zealand in the 1920s, or at least the majority Anglo-Saxon New Zealanders of the 20s, regarded the country as a far-flung archipelago of the British Isles. By the 1970s this was, for young New Zealanders, a distant memory. The values the school attempts to instil in students – fortitude, clear thinking and mateship – feature strongly in the lyrics, with the recurring strain ‘Comradeship, valour and wisdom’. The last verse even harks back to the Roman Empire:

We will fight for the right, honour the brave,

We will keep till we sleep to the rule that Rome gave,

Comradeship, valour and wisdom, Comradeship, valour and wisdom.

Life at boarding school was not all study and the writing of poetry. The great mystery of sex was unfolded for him by a school housemaid, whom he took out to a local park called The Meeting of the Waters in his father’s Baby Austin, and where ‘very expertly and intriguingly she instructed’ him in the art of love.11 He managed for the most part to avoid other physical activities such as sport, for which he had no interest or aptitude.

In early 1931 Stewart left Taranaki for what must have seemed a racing, glittery metropolis – Wellington – to follow in his father’s footsteps by studying for a law degree. In hindsight he was able to describe it as ‘the bleak, windy city of Wellington’, and it is true that the place has an unappealing climate.12 The outlying areas are less windy, but the city itself is built on precipitous hills above Cook Strait, one of the most turbulent bodies of water in the world. It faces into southerly gales while also weathering howling storms from the north, particularly in the spring. Even in these days of global warming, Wellington winters are icy and sleety, and in Stewart’s day heating of the uninsulated wooden buildings would have been rudimentary.

The law bored him to death. So much so that he failed everything, even the few papers for which he had actually attended lectures. He was far more interested in racing his Baby Austin back and forth from Wellington to Eltham for his holidays, and exploring the works of writers introduced to him by a new friend: James Joyce, Edith Sitwell, Wyndham Lewis, D.H. Lawrence and Bertrand Russell, among others. Prime among these was Australian Norman Lindsay, with his ‘baffling but wildly stimulating Creative Effort and his much more approachable “Redheap” (which doesn’t seem to have been banned in New Zealand as it was in Australia, and which we enormously enjoyed for its comedies of adolescent love in an Australian small town, so very like the comedies of Eltham)’.13

Stewart must also have spent a fair amount of time gazing out to sea, just as he must have done during his years at New Plymouth Boys’, except that this time he was focused towards the south or east, rather than northwest. Gazing out to sea is a time-honoured New Zealand pastime, eyes resting on the horizon while contemplating either escape or the arrival of visitors. ‘We felt with ever increasing urgency that beyond the rocky headlands of Wellington Harbour lay the great world, and we must see it.’14

His sentiments were expressed in an early poem, probably published in the Bulletin. Evident is the influence of the poets he was reading at the time, particularly in the repetition of ‘cold’ in the last line. Unmentioned in the list he recalled is, possibly, T.S. Eliot:

Morning at Wellington

Thin stone is in this chill wind from the south:

Thin stone, an essence of those bleak, hard hills

That bulk between the town and the cold surf.

Yes, though it gets its coldness from the sea

That, snowed with moonlight, icicled with foam,

Antarctically glistened all night long,

This current, in its planes like panes of glass

That vertically shear between sheer walls,

Is hardened and made sour with those huge hills,

As though the sharp spurs jutting through the grass

Exhale their own dank breath into the wind.

Like the lean soul of steel, like spinsters’ lips

It has an acid taste, unhumanised.

I think it will be hard for the young birds,

And children’s lips will blue because of it.

If you had ears like mine you’d hear it now,

Bitter with a thin sound that stone might make,

And icy with the far-off ocean breaking,

A cataclysm of surf with frost toned bells,

Coldly on crag and stone and coldly on cold shells.15

The poet gave his location as ‘Maoriland’. This was not only a hangover from the nineteenth century but also a kind of literary affectation on the part of non-Māori writers from New Zealand.

The opportunity to escape the thin stone and chill spinster’s lips of Wellington (although by his own account he had a beautiful dark-haired, dark-eyed girlfriend to kiss at this time) was not so far away, hastened by his total failure at law school. The results came while he was on holiday with his family. It is an insight into the character of his father that Stewart was not made to feel like a failure generally, as fathers commonly do when their sons disappoint them. Instead, he was allowed to come home and think about his future. During this time he got his first job as a journalist, as sole reporter on the Eltham Argus. This was a tiny daily newspaper of four pages, and cost one penny. Stewart was responsible for a column called ‘Tut tut’, which exercised the humour of the period. For example, when he wrote up the window display of woollen underwear in the local draper’s he gave it the headline ‘Winter is drawing on’ – a play on the old word ‘drawers’ for undies.16 Hilarious. He had fans, locals who wrote to the paper to congratulate him on his wit.

The Argus building still stands in Eltham, tattered and abandoned. Someone has started to paint the facade green but either gave up or ran out of paint at the last minute. Beyond the painter’s reach the scruffy pediment, mossy and cracked, announces proudly 1897 Eltham Argus. A stencilled graffiti to one side reads DUDES, the name of a popular Auckland band of the late 1970s. Both newspaper and band are consigned to history.

The country journalist suffered a few romantic misadventures, one of which inspired a poem that brought him his longed-for publication in the Bulletin. Pat Lawlor had begun to man a Bulletin office in Wellington and it’s possible he was looking for New Zealand talent. It was a poem about love and the loss of it. But Stewart was restless. There he was, back in Eltham, a failure at law school, and living with Mum and Dad. He wanted freedom and the open road: the life of the roaming bard.

Fortuitously, a man called Charlie Davey arrived in Eltham with his merry-go-round, and needed an assistant. Stewart left the Argus without a backward glance and toured the North Island, or at least as far as Auckland, where the merry-go-round became an adjunct to a touring circus. In Ōtāhuhu, then an outlying town, he and Charlie had a falling-out. Not willing to return to Eltham, Stewart, a failure yet again, headed north. In the Kaipara he was taken in by an elderly Māori couple, with whom he lived for a week or so.

In his first collection A Girl With Red Hair (1944), published 10 years after this experience, Stewart included a story about his hosts. An excerpt reads:

I looked at the old couple, nodding by the fire, the light on their dark faces. What did I really know about them? What went on in those secretive Maori minds? They weren’t animals. They had their own thoughts, based on a conception of life beyond my understanding. What possible communion could there be between the white man and the native? The memory of that deep, mindless sympathy when we sat quietly by the fire on the wet night was uncannily disturbing, horrible. The friendly little whare was a prison.

He was not to know that it was this story, full of the prejudices of the time, that would incense and inspire Witi Ihimaera, one of the foremost New Zealand writers of the twentieth century and beyond. It is interesting to compare Stewart’s recollection of the story’s inspiration and then to look at how Ihimaera, as a schoolboy forced to read it, responded. Here is Stewart, writing about that adventure in Springtime in Taranaki:

And they fed me, the old couple, next day in their own whare, where the fire smouldered all day on the earth under its smoke hole in the corrugated iron roof, and the big black kettle swung on its iron hook, and, perpetually simmering with what must have been about the most lethal black brew ever known to mortal man, the fat enamel teapot stood by the embers, never emptied of its accumulated tea-leaves but occasionally replenished with a handful of fresh leaves if the liquid seemed insufficiently tarry. We ate oiled watercress, a stringy vegetable; and flat damper bread; and cockles or pipis which were kept, still vaguely alive, in a kerosene tin in a corner and which somebody had gathered a week or two earlier from the Kaipara. They strike me now as a most dangerous form of nourishment, though they never did us any harm. We cooked them, briefly, the shells opened, over the fire. We ate, too, delicious boiled kumaras, with purple skins and soft floury yellow flesh, the king of all sweet potatoes.17

He goes on to describe how the fleas tortured him on his mats in the wharepuni, and how at night he would scrape them from his legs by the handful and chuck them in the fire. ‘The old chief and his wife seemed more or less immune from them,’ he writes, ‘and only very occasionally, when some particularly penetrating bite really got through to him, the old man would say he would pour boiling water over them “tomorrow”. But that tomorrow never came, and the fleas flourished and bit. They were a torment … They were in the wharepuni, too, by the million: in the mats of my bed. I could not sleep for them.’18

He recollects how the couple talked about finding him a Māori wife, and how he helped harvest the kūmara crop by riding a horse down the hill to where the women dug and laboured. They would lay a sack of kūmara over his horse and he would return up the hill to where the men were laying the kūmara in fern-lined pits to preserve them.

Here is Ihimaera, remembering the time he read the story at school during the early 1950s:

I had the same attitude to the story that the Nigerian novelist Chinua Achebe had when he read Joyce Cary’s novel Mister Johnston: ‘It began to dawn on me that although fiction was undoubtedly fictitious, it could also be true or false.’

What was Mrs Bradley thinking? Was she trying to rub our noses in our own pathetic lives? I found the story poisonous, the setting demonic and the Maori characters demeaning. As my Māori schoolmates ducked for cover I was incensed enough to ask Mrs Bradley, ‘Why have you made us read this story?’ Despite her protestations that New Zealand Short Stories represented the best of our writers, I threw the book out the window. Quite rightly, she hauled me before Mr Allen and he gave me six of the best.

My ambition to be a writer was voiced that day. I said I was going to write a book about Māori people, not just because it had to be done but because I needed to unpoison the stories already written about Māori, and it would be taught in every school in New Zealand, whether they wanted it or not.19

Ihimaera’s rage and determination are obvious. We could, in a way, thank Stewart for setting Ihimaera on the road, even though it was a bitter stirrup cup he offered.

I should add here that when Stewart’s daughter Meg read a draft of this chapter she was saddened by Ihimaera’s boyhood response to the story and wrote to me: ‘If Dad was alive to today I’m sure he would be deeply distressed to learn of the affront that the heightened language and sentiment of a short story written by him decades earlier caused to the young Witi Ihimaera. Obviously Dad never intended (as you acknowledge) his words in that story or any of his works to be so offensive or wounding to Ihimaera or other Māori readers (including the Māori members of our own family) and I apologise to them on his behalf.’20

What is clear, from Stewart’s letters, diaries, poetry and plays, is that he was not an overt racist. If the charge of racism is to be made against him it is of the same innate type that infected all new New Zealanders of the time. On his return from the Kaipara he wrote this poem, reproduced in Springtime in Taranaki:

Talk lewder now, and turn the radio

Louder, and shout the whirling darkness down,

And someone lock the door against the snow.

So in a bleak time once I reached the end

Of troubling and pianoing desire.

And dead as stone in age-old leathery silence

Crouched with two savages beside a fire

And as a dog knows, knew them both for friend.

Corncobs and drying shark were hung on wall

And sooty kettle swung from a black chain.

And rain outside, and shadows in. The woman

Jabbed at the embers. And then was still again.21

Had Ihimaera read this his resolve to become a writer would doubtless have been even stronger. In the 1930s the term ‘savage’ was passing from use, and it was certainly archaic by the time Stewart wrote his autobiography. This might well be why he added: ‘“Savage” was hardly the word for these two gentle souls.’22

Living ‘among the Maori’ was not for Stewart. He returned to the Taranaki where he thought he had a girl waiting for him. She was not. He endured his first real heartache and even contemplated suicide, though not for so long or so intensely that he couldn’t fall in love with someone else three months later. Meanwhile, he worked as a journalist on the Hawera Daily News and took up drinking. He continued to send poems to the Bulletin and was regularly published. One such effort is ‘Watching the Milking’, the first verse of which is:

In the ashen evening of a bird’s song spouts in silver

That swirls to the shed where an engine spits and chugs.

The yard is muddy; sunk to the knees, the cows

Await the sucking cups, the hand that tugs,

Content and chewing; and not afraid of man

Or the weird machine that robs their swollen dugs.23

Breasts, ovine and human, are always a source of fascination for masculine young poets. Here is an excerpt from ‘Two Studies’:

The four girls frolic in the water

and their flesh grows warm at the subtle caress of the current

two of them, meeting in the pool

stop

and stand face to face

each with hands on the other’s delicate breasts.24

All young poets, perhaps, should destroy their juvenilia.

Stewart enjoyed his time in Hawera. He reported on all issues, including on one memorable occasion a journey to Patea to interview the prophet T.W. Ratana. His record of this, as set down in Springtime, is rather sneering and not worth reproducing. This was a time of heavy drinking and youthful behaviour, and in February 1931 he was given the sack.

Poetry was all. He wrote prodigiously, sending poems off to magazines in New Zealand and Australia. He grew a thick skin – necessary, perhaps, given the wording of some of his rejections. In September 1931, when he queried a rejection by the New Zealand Magazine, established in 1921 as New Zealand Life, the editor responded in a handwritten note:

Dear Sir,

You ask in your letter: did I find the poem unamusing, dull? To be perfectly frank, I did; and that is why I advised against publication … If you are writing for your own pleasure, well and good; if you are writing for publication (other people’s pleasure) then I think your venture hopeless.

Yours sincerely

The Editor NZM25

Another letter preserved among his papers, not quite a rejection, stands as an example of the kind of response today’s young writers rarely receive. It is dated 10 August 1931 and typed in dashing blue.

University Tutorial School

Masonic Chambers,

Wellington Terrace, Wellington.

Dear Mr Stewart,

I have read the Ms of your burlesque epic with great amusement and a keen appreciation of your felicity in handling an extensive vocabulary. Occasionally you have trouvailles in verbal prestidigitation that a verse writer in Punch might envy … I am inclined to think that your appeal would be more effective if you retained that half of the whole which is best; a heavy demand, as it would involve rewriting a large number of stanzas. After all, not much happens to your hero that could not be put on a sheet of note-paper, and if you rely wholly on your skill with words to interest your readers, that skill must be kept as nearly as possible at its highest level throughout. Your work seems to me good enough to be worth the labour of making it shorter.

Sincerely yours,

GW von Zedlitz26

For around 10 years Stewart had been in correspondence with the literary editor of the Bulletin, the writer Cecil Mann, not only concerning the publication (or not) of his verse and short stories but also in the hope of a possible job. In 1933 Mann wrote to say that there could well be an opening as staff light verse writer. The letter reads, in part:

… as editor of the Mirror I’ve been accepting your verse for some time: now I’m back with the Bulletin, looking after the short stories, Red Page, ‘serious’ verse and suchlike literary matters … I write to see if you’ll let me have first choice of your work; I’ll return what I don’t take so that you may place it elsewhere. Also, are you likely to be over this way? If you are, look me up. You might also tell me what inky experiences you’ve had, for possible future reference. Have you ever, for instance, written ‘light’ verse?

All the best intent

Cecil Mann27

Contemporary writers would be envious – imagine being paid to write light verse! Older New Zealanders will remember Whim Wham and others of his ilk. Light verse was a kind of poetic cartoon, a way of making light of the serious issues of the day. Mann believed that the current staff writer of light verse, Andrée Hayward, was about to relinquish his post. Without hesitation Stewart boarded the Marama in Wellington and made the five-day voyage across the Tasman. He intended to stay for a while at the People’s Palace, a cheap, private hotel run by the Salvation Army, and favoured as safe accommodation for single people as well as families. Built in 1888 on a large site on Pitt Street in the central city, with 600 rooms, it was a New Zealanders’ destination for decades. My own mother, making her first brave foray away from home at the age of 20, stayed there with her best friend when they arrived in Sydney in 1959. The building was demolished in the late 80s.

Stewart would likely have thought that staying at the People’s Palace was part of the usual Kiwi in Sydney adventure and particularly inspiring to a poet, but it is unlikely he was disappointed when Mann changed his plans and took him across the harbour to Kirribilli to stay in the flat he shared with his wife and two young sons. Stewart’s daughter Meg recalls that Mann’s flat was ‘filled with literary atmosphere as well as a sense of Sydney cultural life’.28 Bookshelves boasted first editions from Nonesuch Press, a British publishing company renowned for its handsome editions of John Donne’s poetry, as well as the works of writers such as William Wycherley and William Congreve. On the walls were framed drawings and cartoons from the Bulletin. Beyond the flat were the strident cries of Australian birds and the hum of cicadas, fiendishly loud to New Zealand ears, and fine houses and gardens that spread to the water’s edge. Stewart and Mann went swimming at midnight in the shark-infested harbour, and the following morning drank six bottles of beer. Then it was across the harbour again on the ferry, and on to the Bulletin office. ‘I walked through the turnstiles at Circular Quay into the world of magic I had dreamed of,’ Stewart recalled.29

But Andrée Hayward didn’t resign. Who could blame him? Jobs writing light verse were rare even then. Stewart, still only 26 years old, went instead to Melbourne where he stayed with relatives and tried for six months to make a go of it as a freelance writer. He went to see fellow New Zealander and editor of the Sun, Eric Baume. Stewart recalled his interview: ‘“Oh, writers,” said lordly Baume, lolling back on his chair with his feet on the desk, “I can get writers anywhere. Are you a good sub?” Truthfully, but foolishly perhaps, I said I had had no experience as a sub-editor, and that was that.’30 He did manage, briefly, to find employment as a reporter – on yacht racing, about which, by his own admission, he knew nothing. After Christmas in Melbourne he returned to Sydney to see if Andrée Hayward would at last relinquish his post, but the situation was the same as it was before.

Back to New Zealand he went, wanting nothing more than to return to Australia as fast as he could. He was excited by the men he had met, the writers and artists, the ‘brilliant, hard-drinking men’, and especially the poets Kenneth Slessor and Robert D. FitzGerald, who would become close friends.31

As we all do when we return from our first journey to Australia, Stewart marvelled at how green and lush the New Zealand countryside is, how different the quality of light. He felt that he had fallen in love with New Zealand all over again.

In a poem ‘Haystack’, written after his return, he wrote: ‘The creamy frost of toi-toi plumes/Above the rushes’ blue-green shrilling/Forewarns the farm that winter comes,/But the rich land is not unwilling.’32 Another poem, ‘The Growing Strangeness’, contains the evocative line: ‘The blunt grey statement of New Zealand hills’.33

Love for the beauty of New Zealand, particularly Taranaki, was not so overwhelming that he did not experience an irritation with his homeland. This too is a common phenomenon in young New Zealanders after their first real, adult experience of Australia. It can manifest itself in highly unpleasant ways, annoying family, friends and total strangers, especially if that irritation is published. Stewart tried to publish his. Luckily for him, the piece he submitted at the end of 1933 to the New Zealand Herald, ‘Nelson in Winter: A drive to Takaka green rivers and black crags’, was rejected. It reads, in part:

‘Where are we now?’ I ask. I am being cured of a sentimental predilection for Maori place-names, for in Nelson the English names are all so beautiful that one must believe it was colonised by poets, while the Maori ones are harsh and ugly, sounding as if they were squawked out by quarrelling seagulls. Motueka, Riwaka, Wakapuwaka, and hideous Takaka are the brown man’s legacy: but the white pioneers have given us Rainbow Valley, Golden Valley, Dovedale and Pigeon Valley, Bright-water and Ruby Bay. The biggest natural spring in the word ... is still insulted with the ridiculous Maori [erased] name of Pu-Pu …

He goes on to describe travelling through a valley of inbred idiots and remarks that:

. . . many of the bridges over the big rivers are crazy structures that would not be tolerated in the progressive North … The Maoris, before they were driven away are said to have had five hundred acres under cultivation around Nelson … (these days) the country’s full of unemployed fossicking on the subsidy. They’re making a crust, but these people are different. Three Wellington families, all comfortably off before the depression; went broke, and are making a marvellous fight of it here.34

It was during these few years back in Taranaki, before his departure for good, that Stewart made the acquaintance of novelist and poet Eve Langley, an Australian living in New Zealand. He was so dazzled by her writing that he hoped, on their first meeting, they would fall in love. Given her long battle with mental illness, he had a lucky escape. He visited her several times in Auckland and was to say, ‘[I]t was always the same impression of squalor and down-to-earth peasantry all around her and this vivid flame in the middle of it’.35 Langley wrote in her journal of him: ‘I really do love that boy for his goodness and quiet kindness and his Douglas Stewartness … his red rimmed eyes, his sad down pulled nervous mouth …’36 Their friendship was to endure until Langley’s lonely death in her shack near Katoomba, New South Wales, in the winter of 1974. Langley loved Stewart as a brother, often addressing him as such. He helped her out financially, emotionally and practically many times, and was a great admirer of her feverish, image-rich writing. Langley had a brief, unhappy marriage, and bore three children who were put in an orphanage by their father Hilary Clark while Langley was incarcerated in Auckland Psychiatric Hospital. An extract from one of her many, lengthy letters to Stewart, written in the 1930s, gives a strong sense of her voice and state of mind:

My brother you should know by my silence, that I am busy about forbidden things. The angels are always waving Eve out of Eden. In old days I went out alone, but this time I have contrived to drag a companion with me. I have married him, so I suppose that means that he must come, too.

His name is Hilary, he is a tall black bearded art-student of 22 and he lives alone in his garret, like a wolf, and bawls out, ‘Who the hell’s there?’ whenever I go near the door. Therefore, I don’t go near it, often.

At odd times he will consent to share the marriage couch, but when the clocks strike the long midnight, he says that he hears a motif in them that he must follow, and paces around the room, complaining, ‘god, tonight I feel that I could write a concerto! My Eve, I will away!’ and he buckles on his sandals, and with a delicate flutter of white undergarments is gone.

So, Dhas, I am much alone, and working hard, preparing a book of verse for London. Surely to God they’ll have the sense to see that it’s not worth printing. And a book of fairy tales for the same suffering City, and a book of short stories for the same screaming, outraged place.

Fear and loneliness drive me on, brother, and I will admit them to none but you ... Hilary is a great and glorious drinker; foam lies on his beard, his lips grow rich and wide, and he has a laugh as long as the Wall of China and as loud as a Maori’s blazer … This place at Hernbae (as the Indian greengrocer’s calender [sic] has it) is two rooms belonging to a woman who paints, and for seven and tix [sic] a week I have got it from her for three wiks. It is full of the gimcracks that some women love, and which I love, too, for a while. Little cups and plates and things like a mob of cattle of different brands, all yarded in cupboards … Hilary lives under a big box, for which he pays no rent. It has two rooms, the one below is for him to study and swear and sing and bellow in, and the one above is for the echoes, because his echoes need plenty of space. He really has more belongings than I have, because there is his piano which he rocks like a cradle, and his violin which rocks him, and a bed which is like rocks, and a chair with its jawbone torn out.37

Stewart was captivated by the humour, energy and sense of danger in her writing, and always felt very sympathetic towards her, no matter how irked he was by her behaviour. It may have been that Langley first came to his notice in 1934, when he received a letter from Dunedin asking if he would be willing to contribute to a new magazine called The Golden Fleece. Its mission was ‘to find out literary wealth in New Zealand’. The editor, A.N. Allan, was proud to announce that he had ‘five pounds in Dunedin Savings Bank and a guarantee of five pounds that we can call on’. Most importantly, he wrote, ‘Eve Langley has given us permission to quote from her “Jason of Argo laughs” on the title page.’38 For the magazine to go ahead he needed 560 subscribers at £1 each. Stewart may well have contributed financially. His willingness to support other writers and all kinds of literary endeavour was one of his endearing, life-long traits.

Meanwhile he wrote letters to Australian newspapers seeking work. The Ballarat Courier replied to say there were no vacancies but that ‘Your name has been placed on our list.’ A telegram arrived from the Melbourne Weekly to say his application had been received; a second telegram announced position filled.

Stewart continued sending poems to the Bulletin. A 1935 letter from Mann reads, ‘Work has been so thick that I’ve only now got to your verse. Some of it is splendid – Mending the Bridge, Winter Crazed, the Poplar piece and the … strangeness seemed to me uncommonly full of poetry … the others enclosed I don’t care for so much.’39

‘Mending the Bridge’ is worth reproducing in full for its vigorous energy and imagery. Until the end of his life, Stewart rightly regarded it as one of his best:

Burnished with copper light, burnished,

The men are brutal: their bodies jut out square,

Massive as rock in the lantern’s stormy glare

Against the devastation of the dark.

Now passionate, as if to gouge the stark

Quarry of baleful light still deeper there,

With slow, gigantic chopping rhythm they hack,

Beat back and crumple up and spurn the black

Live night, the marsh black sludgy air.

And clamour the colour of copper light

Swings from their hammering, and speeds, and breaks

Darkness to clots and spattering light, and flakes

Oily, like dazzling snow and storms of oil.

The night that never sleeps, quickens. The soil,

The stones and the grass are alive. The thrush awakes,

Huddles, and finds the leaves gone hard and cool.

The cows in the fields are awake, restless; the bull

Restless. The dogs. A young horse snorts and shakes.

Beneath the square of glaring light

The river still is muttering of flood,

The dark day when thick with ugly mud,

Swirling with logs and swollen beasts (and some

Still alive, drowning) it had come

Snarling, a foul beast chewing living cud,

And grappled with the bridge and tried to rend it,

So now these stronger brutes must sweat to mend it

Labouring in light like orange blood.

Men labour in the city so,

With naked fore-arms singed with copper light

And strangeness on them as with stone they fight,

Each meet for fear, and even the curt drill

Mysterious as trees and a dark hill.

But these are stronger, these oppose their might

To storm and flood and all the land’s black power.

Burnished with sweat and lanterns now they tower

Monstrous against the marshes of the night.40

On 1 July 1973 an ABC programme called ‘The Poems of Douglas Stewart’ was broadcast on Sunday Night Radio Two, presented by Stewart himself. The typescript of the unscripted narration explains the genesis of the poem: ‘[It] dates away way back to my early youth in New Zealand. Think I was about twenty when I wrote it, and oddly enough, I’d just come back from my first attempt to get a job and live in Australia, and that fell through. And when I went back to New Zealand I seemed to be seeing the place with fresh force, almost for the first time.’

Poets of every generation struggle to get their work published. Stewart went into battle with Whitcombe & Tombs over his first collection, Green Lions. Following an initial request that they read the manuscript he received a letter, dated 11 September 1935:

… as you probably know, the market for poetry in Australasia is small and as a rule we undertake publication only at author’s expense. However, if you care to submit your selection we will consider them and report to you as soon as possible.

Yours faithfully,

AW Shrimpton,

Editor41

A month later, he received a further communication:

Dear Sir,

Yours of the 29th of September has been under consideration for some time. We have no wish to incite you to reckless expenditure but as you seem keen to have your verses in print we will see if we can help you … We will estimate the cost of production in the style say of Jessie Mackay’s recent volume, Vigil, which you have no doubt seen.

AW Shrimpton42

By 6 November his demands were starting to annoy Shrimpton:

… I have to say that your condition re window display is impossible. It would not pay any bookseller to do more than give a little space to a book of poetry, particularly by an unknown author and at the Xmas season. Poetry sells badly at any time and window space is valuable. Few copies are selling of Vigil and Miss Jessie Mackay is well known … We cannot control window displays by our branches and our Australian houses have no windows. Neither can we dictate to other booksellers, who, of course, fill their windows with stuff for which there is a known demand.

Your other condition re having the book out to catch Xmas sales I regret to say is practically impossible too. You perhaps don’t realise that there is no profit for us in this job at the price quoted.43

It seems that that Stewart asked his father for help in this regard – and that he had already suggested his father read The Wasteland so that he had some conception of what his son was on about. A letter from his mother confirms:

We’ll think hard about ‘Green Lions’ and act in due course.

Pop’s got to find out what kind of book T.S. Eliot’s Waste Land is before he accepts your kind offer – let you know the result later – suppose it’s too indecent!44

In the end, his loving mother contributed £50 towards his book. Stewart himself would have had additional funds to contribute. When Green Lions roared into print in 1936 he was editor of the Stratford Times, a job that would have paid not a lot but more than enough to keep a young single man who was living at home. A letter from Mr Shrimpton in January of 1937 informed Stewart that all Whitcombe & Tombs’ outlets had been supplied with the book and the rest were in the warehouse awaiting his instructions. Many poets are too self-effacing, lacking in confidence or ignorant of the power of connection to do much more than get their books into print. Possibly because of his years as a journalist, Stewart knew better and didn’t waste any time, sending copies not only to the Observer and possibly other newspapers but also to poets he admired, most particularly John Powys.

It was the publication of Green Lions that gave him the impetus and will to leave – not for Australia, as he’d always planned, but for England. He was flying high: his first book had been published and he was in love with a Taranaki woman called Daphne, whom he intended to marry. Powys also knew about her, which shows that their correspondence was about things personal as well as poetical. Powys may even have met her, since Daphne went to England later in the year.

The main problem that confronts all young New Zealanders going to live in England is how to survive. Stewart, once he started working on it, was well connected. W.J. Green, editor of Wellington newspaper The Standard, wrote a letter to Prime Minister Michael Savage in April of 1937:

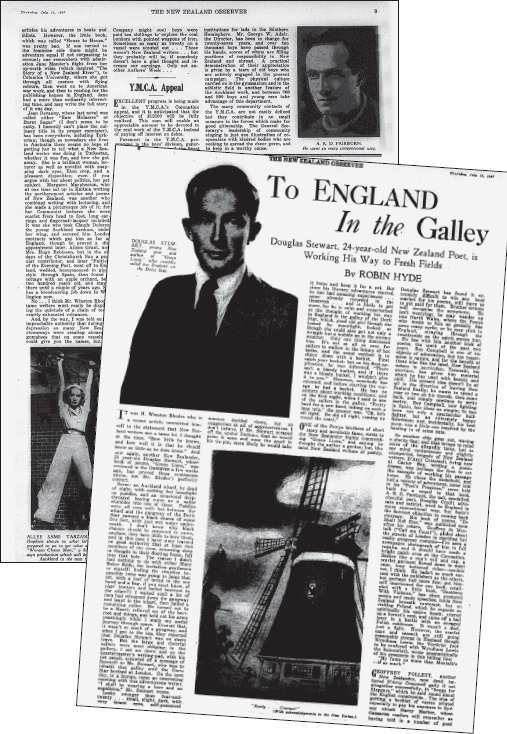

A studio portrait of Douglas Stewart as a young man, just before he worked his passage to England in 1937. Brandon Haughton photographer, Hawera

Mr Douglas Stewart has asked me would I give him a letter of introduction, as he is desirous of covering your movements and your reception in England for THE STANDARD.

Mr Stewart has recently published a book of poems which has been very well received in New Zealand and in Australia, and has been described by ‘The Sydney Bulletin’ as the best poet in this part of the world today. He is a fully experienced journalist, having worked in both Sydney and Melbourne as well as in New Zealand cities. Prior to leaving for England he was editor of ‘The Stratford Evening Post’.

I may mention incidentally that he was a foundation member of the Labour Party branch at Eltham, but his subsequent connection with ‘The Stratford Post’ forced him to keep his Labour views in the background.45

In the same month he obtained two cards from his uncle Maurice FitzGerald, county engineer for the Matamata County Council. FitzGerald’s name was printed on the front of the card, with ‘Tirau New Zealand’ beneath. On the back he had written:

Introducing Douglas Stewart, my much travelled journalistic nephew to

Mr AA Dorliac

15 Rue Bartholde

Boulogne-Sur-Mer

France.46

There were identical cards addressing a barrister in Bristol and Sir Seymour Williams of Warmsley Lodge (also a barrister). The cards appear unused, as if Stewart forgot to pack them or make use of them. He also had a letter of introduction dated 27 April from L.M. Moss, a barrister and solicitor in New Plymouth to the High Commissioner for New Zealand, London: ‘This letter will introduce Mr DS son of Mr AA Stewart, Barrister and Solicitor of Eltham.’ The lawyer goes on to say that he has known the family for many years and that Stewart’s newspaper work and Green Lions have ‘received favourable notice here and in Australia, and although he has had very attractive offers to remain in NZ, I feel sure that he is wise in seeking wider experience in England.’47

The day finally came when Stewart boarded the Doric Star in Wellington. He was to work his passage to London as Third Pantryman. In Auckland, a journalist went on board to interview him for the New Zealand Observer, and headed her article ‘To England in the Galley’. The journalist was none other than Robin Hyde. He let her know she would recognise him by what he wore – ‘a beer and an aspidistra’. She describes him as looking ‘younger than four-and-twenty … small, slight, dark, with very intent eyes, self-possessed manner, decided views, but no suggestion at all of aggressiveness’. She related how Stewart had received a letter from John Cowper Powys and that the English poet thought the New Zealand one a genius, ‘but, like most New Zealand writers of poetry, Douglas Stewart has found it extremely difficult to win any local market for his poems, still more so to get paid for them. Brother writers will recognise the symptoms … So another ship goes out, waving a plucky flag.’48

‘Like most New Zealand writers of poetry, Douglas Stewart has found it extremely difficult to win any local market for his poems,’ wrote Robin Hyde in a newspaper feature as Stewart left the country. New Zealand Observer, 15 July 1937

Stewart’s sojourn in England was to last less than a year. He spent time with Powys, he worked in a bar and made the discovery that most young colonial poets do sooner or later, which is that everything in England seems to have had prior claim laid to it by the centuries of native-born writers who came before us:

But England, just when I was beginning to feel I could survive in it, increasingly filled me with dismay. I was not writing my customary poem a week. I was not writing anything. Moreover, I could not see where I could ever make a start. In the kind of country writing in which I was interested, everything in both verse and prose seemed to have been said before. ‘That’s Hardy’s moor!’ Yes, and that was W.H. Davies’ skylark, if it wasn’t Shelley’s or Wordsworth’s or Shakespeare’s …49

He wrote again to Cecil Mann in Australia, this time suggesting that he take over a page called ‘The Long White Cloud’, which dealt with New Zealand issues. The Bulletin expressed interest, though made no commitment. It was enough to get Stewart on a ship back to Sydney, the city that was to be his home for the rest of his life.