Go out into the street in New Zealand or Australia and ask anyone under 30 about the significance of the year 1939 and chances are he/she won’t know. In universities around the world history departments are shrinking. The subject is less and less popular even at high school, suffering the twin effects of the market imperative for vocation-driven courses and the narcissistic desires of the so-called ‘selfie’ generation. History is boring because someone else did it.

I begin this chapter early in 2017, two months after the election of President Donald Trump in the United States of America. I have no idea what will have come to pass in the time that will elapse between my writing these words and you reading them, but if the predictions are correct then the world may well be enduring another war of similar dimensions to the one that began at the end of 1939. History proves its value in times of upheaval. The word ‘Orwellian’ has recently been thrown around by journalists in the Western world, and sales of 1984 and Animal Farm have peaked. Young observers will also be learning the meaning of the word ‘fascist’, if they didn’t already know, as well as newly coined terms such as ‘alternative facts’. The internet will define these terms for them, rather than books. The Guardian website sees a massive increase in traffic whenever it runs an article on the lead-up to World War II and the way the politics of hatred are mimicking those that made it possible for Hitler to rise in Germany.

Early 1939 finds our New Zealanders only just beginning to suspect there could be another war. The closest conflict is in China, two years into the Japanese invasion. In faraway Europe the Italians are conquering Albania, Russia invades Finland and very soon the Germans will invade Czechoslovakia and Poland, signalling the beginning of the conflagration. Closer to home, the first Jewish refugees from German-occupied countries are beginning to arrive. In April, Australian Prime Minister Joseph Lyons dies and Earle Page succeeds him. His term lasts for less than three weeks before Robert Menzies is selected leader of the United Australia Party and begins his first term. Eventually, after serving a second term in the 40s and 50s, Menzies will become the longest-serving of Australian prime ministers, who traditionally have short periods of incumbency.

Fully established in Australia, Jean Devanny has added to her substantial list by publishing two books in two years: Sugar Heaven in 1936 and Paradise Flow in 1938. The year Paradise Flow is published, the Writers’ Association – of which Devanny was first president – joins forces with the newly established Fellowship of Australian Writers. After a long and tumultuous affair with J.B. Miles, the general secretary of the Communist Party, she is separated from husband Hal and spending much of her time in Queensland. This year she will be expelled from the Communist Party, a tearing loss which upsets her – but not as much as the death of her son Karl five years earlier: ‘For the second time in my life the sun went out.’1

Last year, in 1938, Roland Wakelin was represented in a highly prestigious exhibition, 150 Years of Australian Art, at the New South Wales Art Gallery. He had three paintings included, his first in a museum exhibition. This year sees another solo show at the Macquarie Galleries and another shift in residence, this time to a flat on the corner of Challis Avenue and Victoria Street in Potts Point. He is 52 years old and assured of his place in contemporary Australian art.

Forty-nine-year-old Dulcie Deamer has also been in the limelight. Last year her play Victory was produced. This play, along with most of her others, is now lost. She is resident in the Cross and living life, as always, to the hilt.

Douglas Stewart is returned from a few months in England where he made the acquaintance of a long-admired poet, John Powys. Early in 1937, a year before he left for England, he proposed to painter Margaret Coen. This year they are halfway through their long engagement and he is in his first year of his long-coveted job as assistant to the literary editor for the Bulletin. A volume of his poetry, The White Cry, is published in London. After all the success and excitement, the year ends sadly. In October Stewart’s mother, to whom he is very attached, passes away in New Zealand.

Of our five friends, 1939 is the most seminal for Eric Baume. This is the year he leaves for London to work as a war correspondent.

We last spent time with Eric Baume when he was 23 and on his way to Australia. It was his first confessed experience of loneliness. He recalled that on the second day of the voyage he watched ‘North Cape fade into the clouds, just after dawn when the decks were wet. I was alone. My eldest daughter, Nancy Jean, was far too young to travel. My wife’s health would not permit an early trip for her.’2

Describing Baume’s first night alone in Sydney in the Metropole pub, biographer Manning says ‘loneliness hit him like a punch’, before going on to remark how quickly the young man would, ‘like so many migrants from New Zealand’, fall in love with Sydney.3 His New Zealand origins were not forgotten. Bill Olson comments in his 1967 biography, Baume: Man and beast: ‘People who knew Baume well often wondered about his New Zealand birth. That such a green, quiet, pleasant place, where even the geysers are predictable and the inhabitants passive, could cradle a poor man’s P.T. Barnum such as Baume seems incredible.’4

Among Baume’s shipmates were some other newspapermen who were also going to work on the Guardian. The newspaper world of Sydney would neither welcome nor trust them, thinking there were far too many of them and that they were pushing Australians out of the birthright of their jobs in an already cut-throat environment. Most of these migrant ink-slingers found good jobs, early examples of successful New Zealand journalists who still abound in Australia today.

Packer’s Guardian survived for six years, setting the low standards for the tabloid gutter press that would flourish later in the century. Crime was its main form of sustenance. ‘Executions were meat for us,’ Baume recalled. ‘I remember featuring on the front page the death struggles of Williams, the violin-playing murderer who had killed his two little daughters.’5 His investigations were sometimes aided by the police, who had given him a blue press pass with ‘New South Wales Police’ embossed in gold letters. On one occasion he used it to wrest information out of a man who had transported a woman’s body from a Coogee block of flats. The body was concealed in a trunk, and the man was unaware of what it contained. The Daily Mail quoted him: ‘A tall, dark man looking like a policeman showed me a detective’s card, and I was frightened and spilled my guts.’6 Voltaire Molesworth, the managing editor of the Guardian, stole photographs from the dead woman’s flat and took copies before returning them to the police. This kind of activity, described by Baume as ‘flashy’, earned the newspaper many readers but also approbation.

Recalling his professional life during this time Baume believed he witnessed ‘cynicism, brutality, even horror; so there were times in Sydney when I would have given the world to return to some tiny New Zealand town and write a paragraph in some dull, virtuous sheet about what a well-meaning pillar of municipal government had to say on mismanagement of the local pound’.7

The newspaper folded after six years, thanks to the advancing Depression and to New South Wales Premier Jack Lang. Managing editor Molesworth, who may well have been a member of the fascist organisation the New Guard, had never been sympathetic to the Labour Party and did his best to destroy Lang’s reputation. On Packer’s instructions Baume himself had joined the organisation so that he could watch its every move and report back.

When Lang became premier he had introduced what became known as the Packer Bill, which aimed at parliamentary control of aspects of reporting on political matters. Firmly in the centre of Lang’s sights was Packer’s popular newspaper the Daily Telegraph, which had run reports on Lang’s preference for and support of the Labor Daily. The premier himself was a shareholder and director of that paper. Had the bill been passed, Packer believed, he would have lost everything. As it was, the bill was thrown out and Packer, whom most recall as an unpleasant man with very few friends and many enemies, escaped ruin. Not long afterwards he was injured on his yacht and was forced to give up work. He made a trip to England and died during the voyage back to Australia.

In the meantime, Baume was ambitious and energetic, finding time to write two books as well as working for a number of papers before being appointed editor of the Sunday Sun, the largest newspaper in Australia, in 1932. It was during this decade that he and his wife Mary moved to Gordon on the upper North Shore, having previously lived in Cremorne and Roseville. Baume had had a full year of freedom before Mary joined him. The birth of two more children and his wife’s ongoing illness did not seem to alter his bachelor-like behaviour, aided by a large amount of money. He was one of the highest paid journalists in Australia, earning between £1500 and £2000 a year. The house was surrounded by a hectare of leafy grounds and the Baumes entertained lavishly, hosting parties of up to 40 guests. Mary, suffering unbearable pain from advancing rheumatoid arthritis, would at least have had him home on those occasions. Very often he was somewhere on the other side of the bridge, chasing stories or gambling and drinking, AWOL for 24 hours at a time. It was, understandably, a troubled marriage. There were periods when he lived away from the family and his role of comforter was taken over by a family friend, who came to live with them from New Zealand and stayed for many years.

Baume saw the pre-war period, once the Depression started to recede, as a kind of fool’s paradise. He recalled: ‘Australia least of all realized the German menace … I can remember the doxologies … sung at every cocktail party given by the Japanese in Sydney, attended by a slobbering bunch of socialites as well as a tail-coated assembly of minor German and Italian officials.’8 He had something in common with Devanny in that a novel, his second, was banned at this time. This was Burnt Sugar, set in Queensland and abounding with Italian characters. In typically bombastic fashion Baume believed the banning came about because ‘some of the statements against Fascism offended the Fascists’.9

Two years before the declaration of war, Baume left for America at the request of politician, philanthropist and newspaper magnate Sir Hugh Denison, who wanted Baume to buy features for a new weekly. As he headed across the Pacific aboard the liner Monterey he relished every moment of the slow voyage. Apart from half a dozen short trips to New Zealand, he had done 14 years’ hard yakka in Australia, a period he described as ‘unutterable turmoil’.10 By this time he was the author of three books, various highflying jobs on newspapers had come and gone, and his arrogance and uncompromising nature had earned him many enemies. His nickname ‘Baume the Bastard’ had less to do with alliteration than his behaviour. More intimately, he had been swallowed by grief at the death of his beloved mother in 1934. As he followed the funeral cortège up to the Wellington cemetery he had vowed to become a better man, but hadn’t quite managed it. Just as traumatic was the recent implosion of his once close friendship with Packer. Baume felt it keenly, stating that Packer had been like a father to him. Biographer Manning comments, ‘I’d be prepared to say Packer’s was the only regard Baume ever valued at all.’11

En route to America Baume filed stories from Fiji and Mexico. A whole chapter of his I Have Lived These Years is given over to his experiences in Suva, where he visited a hospital built with American money. He met young Fijians who were training as ‘native practitioners’ – that is, not as fully qualified doctors. This gave him the chance to expound his theories on race, which he would later attempt to express as fiction in his appalling 1950 novel Half-Caste:

No native is ever happy completely in his associations, professional or otherwise, with those of the alien race who, by the glory of God and their great-grandfathers, regard themselves with a superb superiority. Even the New Zealand Maori, whose blood courses to-day throughout the veins of thousands of most prominent New Zealanders, is never completely at home in his full-blooded state with his white associates. The Australian black, more negroid, more strange and ancient, is never at ease with the white man … The fact that the Maoris have had knights such as Sir Apirana Ngata or Sir James Carroll, or vivid politicians such as Tau Henare, does not suggest that within his own mental processes the native recipient of formal honours casts aside his own prejudices and ignores the prejudices of others.12

Much ink has been spilt on the idea that the two world wars of the twentieth century helped to unite indigenous people and colonists, in that soldiers were drawn from every race and all went off to fight a common enemy. The land wars of the nineteenth century, about which Baume’s childhood gardener had poured stories into his eager ears, came well after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in 1840. The promise of equality, to many Māori, was proven to be a lie. Subjugation could not and would not ever be willing. At the time Baume was writing, the late nineteenth-century idea persisted in both Australia and New Zealand that the original inhabitants of both countries were dying out. I have already mentioned the memorial on Auckland’s One Tree Hill, which was erected for that purpose – ‘to smooth the pillow of dying race’. Māori, it was thought, would disappear through the effects of disease and poverty. It is a horrifying notion to us now, but as Michael King points out this was not necessarily a ‘derogatory gesture’ but an expression of ‘respect and regret on the part of Pakeha who admired Maori’.13 By Baume’s time, intermarriage was marginally less frowned upon but seen as another cause of demise – the race would become diluted. In the 1980s Dame Whina Cooper was the last great exponent of intermarriage, and she was roundly criticised for it, even though it was her belief that it would save Māori.

After a period in Honolulu, where he had a Japanese secretary entirely unapologetic for Japanese actions in China, and who convinced him that a major war was imminent, Baume went on to San Francisco. He was back in the city where he had precociously come of age, but in the late 30s it held no fascination. His right-wing sensibilities were offended by what he saw as the ‘modern American system of picketing’ as people protested against late-Depression inequality.14 He repaired to his uncle’s ranch, and then to Hollywood, where he was guest speaker at the Authors’ Club and made an ill-received joke about America being formed from the manure of Noah’s ark.

The promise of a good story drew him down to Mexico. The high incidence of violence shocked him, but not as much as the extreme poverty, particularly the sight of homeless beggars shivering on doorsteps through the night. In Sydney he had been a ‘street angel’, and no doubt he was again here, forking out his loose change. It is often noted that people who espouse right-wing politics, and are particularly critical of state aid to the disadvantaged, will be personally generous. Throughout his life, Baume epitomised this dichotomy.

After an off-the-cuff remark to a Guadalajara newspaper that land reform, for some mysterious reason, reminded him of Australian legislation in respect of the allocation of farmland, he was written up as an ‘Australian Communist’. This so earned the admiration of the administration that within his first day in Mexico City he was appointed Honorary Consul for Australia and New Zealand. The Australian newspapers forbore to write this up, since it was seen as an example of Baume the Bastard-type behaviour and best ignored, but it was proudly reported in the New Zealand Gazette. Not surprisingly, anti-communist Baume didn’t want the job. It took nine months to extricate himself – an irksome and time-consuming process, mitigated by his meetings with Leon Trotsky, who had been offered asylum in Mexico at the end of 1936. The articles that resulted from their conversations were syndicated in the United States and published in Australia. Jealous of Baume’s access, and managing to express both anti-Semitism and loathing of communism in one breath, the Bulletin announced that Baume ‘had been granted the interviews through the brotherhood of circumcision and had no right to print anything Trotsky had to say’.15

Indications that Germany would be an aggressor in a coming war were mounting. Trotsky himself predicted it during their conversations, and in Mexico City Baume met undercover Nazi airmen and soldiers working in menial and sales jobs. He was glad to get back to Sydney where he resumed his editorship of the Sun, and also began broadcasting on the 2GB network, a precursor of the ABC.

It must have been a conflicting time. Always proud of his German ancestry, he was now convinced that Germany would bring about another war. His commentary on the matter earned official complaints from Dr Asmis, German consul-general. The broadcasts were discontinued as a result. When Associated News introduced a new rule that editors were not allowed to broadcast, he lost his job. For the first time in many years, Baume had no income.

By the end of 1938 Mary was extremely ill and his three children were at boarding school, both factors that made life expensive. He needed a fairy godmother or, at the very least, a patron. His wish was granted but, as is often the case when wishes come true in fairy stories, with some unfortunate consequences.

The fairy godmother was the wealthy widow of a grazier, who wanted Baume to go into politics. Doubtless she had read his articles in various newspapers and perhaps listened to his broadcasts, and decided their politics were of the same deep blue. One of her first gifts was a gold cigarette case. Despite later admitting to his biographer that it made him feel like a gigolo, he didn’t return it. Nor did he return the £2500 she slipped him one evening after he took her to dinner at the Australia Hotel. The gifts kept coming. Over the years he received from his admirer over £20,000, a phenomenal sum. It would come back to bite him.

In Europe war drew ever closer. When Ezra Norton, the managing director of the Truth group in Australia and New Zealand, offered Baume a job as foreign correspondent in England for £50 a week, he didn’t hesitate, even though he would be leaving his grievously ill wife. The promise of adventure was irresistible, and so was the salary: an increase of £10 on his previous weekly income. On 15 September 1939, 12 days after the war began, he left for England.

At first, given his heartfelt identification as a wild colonial boy, the class system and snobbery of England intensely annoyed him. But in common with the experience of many colonials, he was soon just as intensely seduced by it, especially when the seduction later took the form of an actual lady willing to slide about with him on the black satin sheets he had especially made for his bed at the Ritz. He was ‘duchessed’, as the expression was: utterly won over by the baubles, fine living, good wine and country piles of the aristocracy. He made the acquaintance of T.S. Eliot, King Zog of Albania and the Marquess of Londonderry; he frequented the Casino, the Café de Paris, the Ritz and the Mirabelle, places he had previously only dreamed about. He must have felt he had achieved his rightful place at the centre of the world.

But he wasn’t to hang around in England for long. Norton wanted him to go to France, to Arras, to be stationed among French troops. The Battle of Arras in 1917 had produced some of the bitterest fighting of World War I, and Baume, desperately keen to see active service – an ambition that had been with him since boyhood – was glad to accept. At long last, a real war. His own war. In preparation, and so that he looked the part, Baume had three diggers’ hats made: one for himself and one each for the two Australian journalists who were to accompany him. Bizarrely, he was resentful that he hadn’t been issued with an Australian uniform. Equally as odd were the manufactured hats that were not exactly diggers’ hats, being slightly out in dimension and style.

Arras was a disappointment. This was the ‘phoney war’, soldiers marching up and down, doing target practice, playing cards, drinking and generally hanging around through the snowy winter, waiting for action. There was a brothel, of which all made full use. Ronald Monson, one of the Australian journalists obligingly wearing a pseudo-digger hat, remembered that Baume made their time there more interesting. Opinionated, brash and militaristic, he would have been in a fervour, and never so much as when Englishwoman Unity Mitford, whom Hitler had been romancing, was shot and injured in a Munich park and arrangements were made to fly her to London. Baume conceived the idea that she had with her the terms of a peace agreement. It was a total fabrication, his novelist’s brain at war with his instincts as a journalist. He wrote up the story and sent it back to Australia, where it duly appeared in Truth.

His Australian colleagues stuck alongside him in Arras must have been dismayed. Monson certainly remembered being appalled when Baume gave a lecture, airing his opinions on what swines the Germans were and how the Australian Aborigine should be exterminated.

And here we will pause for a moment because many readers, justifiably offended, will either flick ahead to the next chapter or put this book down entirely. They could ask – why should a man like this be remembered at all? What possible benefit is there in remembering his life and his opinions? The man was an amoral, puffed-up, violently racist liar.

Racial prejudice, one of the greatest cruelties perpetuated by humanity, has the quality of gathering prisoners as it goes. As a boy, growing up in a society that was already fairly secular at the turn of the twentieth century, Baume was subject to anti-Semitic taunts. His German ancestry drew fire during World War I, not aided by his frequent trumpeting about the Ehrenfrieds of Hamburg, his maternal grandmother’s family, who had once been exceedingly rich and in possession of a fleet of ships that they used for cargoes of leeches among other goods. Some of the epithets accorded him in Australia, inspired by his dark complexion and black curly hair, were purely racist. The rumour that his family was of Middle Eastern origins spawned nicknames that riffed on Baume the Bastard – the Black Bastard, the Syrian Bastard, the Afghan Bastard.

Those who are subject to racism will very often exercise it themselves in a subconscious attempt to elevate their perceived low standing. All antennae are primed to pick up the smallest slight; skins are thickened; the judgements made by others are internalised and expressed in the worst ways possible. We could argue that Baume’s pronouncements put him on a parallel with those who had discriminated against him. They made him feel that he was up there with the big guys, that he was one of the winners.

I am not excusing Baume for his genocidal racial discrimination. There have been times, working on this book, when I considered jettisoning him altogether from the narrative. If Baume and I had co-existed, and if we had ever met, it is highly likely we would have despised one another. He’d have seen me as a soft pinko nincompoop with unfortunate feminist tendencies, and I’d be cowering from his overblown, aggressive misanthropy.

But as I work on it here in Auckland in early 2017, when the world seems to be on the brink of a rise of a new, corporate species of fascism, I find myself thinking about how biographers and historians are themselves more often of left-wing leanings than of right, and subsequently are attracted to subjects that reflect that. And yet, if we are not reminded of how people of all persuasions lived, the opinions they held, their relationships, careers and the long-reaching decisions they made, then the breadth of our understanding is narrowed.

It would be extremely naïve to suggest that men of Baume’s political persuasions do not still exist. In fact, we could say that there are more of them than ever and that they are enjoying renewed influence. They may not openly suggest the extermination of an entire race, but the motivation is still there. Witness the response of the American government to the events surrounding the Dakota pipeline. It is more vital than ever that all of us extend tolerance and empathy to people of different political persuasions so that we can demonstrate another way of being. If Baume was still alive, and if he was reading this, he would likely snort with disgust and accuse me of high handedness, or a sense of moral superiority. He was a man who did not enjoy arguing with women, even though his last burst of fame was predicated on exactly that.

His wife argued with him, when she was well enough. He recalled an incident, while they were driving across the Sydney Harbour Bridge some time before the war, when Mary punched him hard on the nose, twice. He had said ‘a filthy thing’ to her, and the poor woman, who did not appear to possess a shred of violence, found this to be her only possible response.16 He owned that the punishment improved him, doubtless because it was the kind of punishment he understood.

Soon after Christmas 1939 Baume returned to London, where Mary joined him briefly. He escorted her back to Sydney by air, but within 24 hours of landing was on his way back, since in his absence the war had properly begun. On arrival, his German surname caused consternation among the customs officials. He was held up for three hours before convincing them that he was a New Zealander and an upstanding member of the press corps.

Now that the war had reached England, Baume was vindicated. He had raised ire in the months before by criticising British imperviousness, their seeming conviction that London was safe from the bombs. Now that the Blitzkrieg had begun he was in his element, wandering around the city in a tin hat and carrying a sleeping bag, so that he could kip in between gathering stories. He travelled around England giving lectures for the minister of information, apparently to audiences that numbered in their thousands. He embarked on an affair with Lady Margaret Stewart, who added to the excitement by convincing him that his phone was tapped. When his accommodation suffered in a raid he moved to the Savoy, where he took on a suite. The bedroom was his private domain; the sitting room he turned over to become his news office. The desks were pushed to the centre of the room, and Baume, wearing one of the fake uniforms he had had run up to his own design, strode about, dictating his stories in a loud voice. He had a cable service installed and bought typewriters. Telephones rang at all hours. Teleprinter machines spewed cables; maps and photographs were glued to the Savoy’s pristine walls. There were piles of dirty plates and cups pushed into the corners. Once word got out that Baume basically kept an open door, allied servicemen on leave, as well as correspondents from other newspapers, thronged in and out. Noël Coward kept a room upstairs and would sometimes visit. New Zealand pilot Jimmy Ward, who would later win the Victoria Cross at the age of 22, poked his nose in. Lady Oxford, widow of ex-Prime Minister Asquith, was a regular visitor.

Baume built his little empire. A story circulated about how he had paid £80 to have his uniforms run up and those black satin sheets sewn for his bed. Tongues wagged about Lady Margaret, whom he had put on the news team. He appointed an old school friend from Waitaki Boys as his chief of staff. This was Dr Angus Harrop, who after the war would establish the weekly New Zealand News UK paper: it survived for 79 years before losing its life to the internet. Some of the younger journalists who cut their teeth in the Savoy newsroom went on to have brilliant Australian careers. New Zealand-born Keith Hooper was one of them, but not until after his incarceration in a German prisoner-of-war camp. Robert Raymond, who would later become producer on the famous and much-loved Four Corners weekly television programme, started work for Baume when he was only 19. New Zealand-born Elizabeth Riddell, who would garner fame not only as a journalist but also as a poet, was also on the staff.

The working day began at four o’clock in the afternoon and Baume would be up and down from the bars and restaurant downstairs. Often he would drink with the American correspondents who had far bigger expense accounts than he did. Besides, he needed his own lesser one to entertain his mysterious sources. Raymond, looking back on that period of his life, could only marvel that despite the fact many of Baume’s bulletins had to be altered, being ‘sensational, inflammatory and false, his predictions about the next stage of the war were so often proved to be correct’.17 His biggest scoop was his correct prediction of the date Russia would enter the war. He wrote it up and cabled it away to Australia days in advance of its happening. Lady Oxford was likely the source of this top-secret military information, and she in turn would have got it from Prime Minister Churchill, who was not fond of Baume. The antipathy was mutual: Baume thought the PM was soft, and couldn’t understand why full-scale bombing of German civilians had not yet commenced. He had other criticisms of Churchill, to do with ‘drink sodden officers’ and poor security at the Savoy. In his turn, Churchill would have liked to expel Baume for being ‘unwise and disloyal and treacherous’.18

Further smuts adhered to his character when the Australian Smith’s Weekly uncovered the story about the wealthy widow’s gifts of thousands of pounds. Baume wanted to sue the magazine from London, and would have done so, probably unsuccessfully, if it hadn’t been for editor Ezra Norton talking him out of it. Another black spot was Mary’s receipt of an anonymous letter telling her about her husband’s hanky-panky with Lady Stewart. There is no record of how Baume smoothed that one over. Perhaps Mary, knowing her husband as well as she did, was not surprised. Baume was not the kind of man to think faithfulness to a wife was important. And because of her painful illness, their intimate life – on the rare occasion he was actually home – had ceased.

Poor character reports, the Savoy newsroom, the war and Lady Stewart may have combined to become an irksome burden. Whatever, Baume decided he was in need of a personal outlet and that he would revive his career as a novelist. By 1941 he had already published two novels and a volume of memoir. The novels Half-Caste (1933) and Burnt Sugar (1934) had earned him few accolades. He thus treasured a letter from no less than famous writer and journalist Dame Mary Gilmore, who had read Burnt Sugar, set in the sugar plantations of Queensland, and told him, ‘it is a sculpture and it is a memorial, and it is a very fine thing to have done it’. Even better, poet Kenneth Slessor reviewed the novel and mentioned ‘Mr Baume’s astonishing power’.19

Half-Caste is the novel about which Dulcie Deamer took him to task at a meeting of I Felici. We’ll take a closer look at that later.

Baume was very proud of the fact that he could, he thought, write effortlessly. He dictated his books to a harried typist, boasting that he could turn out 100,000 words a day, and that he never rewrote anything. Waving his arms, he would act out the scenes. In this manner he amused himself through the war years by writing four more novels, one of which he declared later in life made him ‘blush with shame’ and another he thought ‘the worst book in the English language’.20 This latter, Sydney Duck, sold an astonishing 800,000 copies and was translated into German and Dutch, a success deemed by its creator to relate only to the fact that few books were being published at the time.

At the end of 1943 Baume made a trip back to Australia, having not seen his wife and children for four years. During his absence war began on the Second Front, a development he’d predicted. He was devastated to have missed it, and got on a ship back to England as quickly as he could. He then travelled across the channel to France for what he would remember as the most important nine days of his life. It must have seemed to him that everything up until then had been a rehearsal.

In Paris he joined the Second Army, got hold of a jeep and a Mexican driver, and made his way to Brussels. A high point was witnessing the battle of Arnhem, actual front-line conflict, which meant that he was forever able to refute accusations that he spent the entire war at the Savoy. It was a vicious fight with huge losses on either side. Afterwards he and journalist Monson went on ahead of the army into Holland, passing dead American paratroopers on the way, some of whom he recalled had died with their hands clasped in a plea for mercy. Both he and Monson were subjected to shelling, though neither of them was hit.

Inspiration for his novella Five Graves at Nijmegen came from a battle over a bridge. After the Allies’ victory, the Germans were made to pick up the British dead and bury them in the grounds of a hotel. The experience made an enormous impression on Baume. Many men, when they returned, would think of war as state-sanctioned murder. Baume would always be a militarist. He was sure that had Hitler not committed suicide, the Germans would have gone on fighting until the end.

Back in the comfort of the Savoy, Baume continued to file reports and to field accusations that he got all his information from brothels and pubs. After his nine-day Boy’s True War Adventure, those criticisms meant nothing to him. He had his blue-blooded mistress, he had his best-selling novel Sydney Duck, he had seen real fighting. On VE Day he took Lady Margaret out for dinner – the woman who, after her death, he would describe as plain and dumpy and only ever a friend.

After VJ Day he went to Norway, where he attended the trial of the fascist politician and collaborator Vidkun Quisling. So famous was this trial that it bequeathed to us the word ‘quisling’, meaning traitor. When Quisling was found guilty, Baume paid various people off in order to get, in true tabloid style, a photograph of the execution. He would have got it, and it would have been a scoop almost as big as the Russian offensive, but the camera was faulty and he missed the money shot.

Baume would have been one of few people mourning the end of the war. He certainly didn’t hurry back to Sydney, travelling in the immediate postwar months to America, Germany and around Britain, filing stories for Truth. When at last he was called back to Australia, it was to take over as editor-in-chief for the Truth group. Rather than returning to live with his wife and children, he took a flat in Kirribilli. Many men found it difficult to readjust to domestic life after the war, but usually because they were traumatised by their horrific experiences in the battlefield. Getting about in his individual uniform adorned with a Croix de Guerre given to him by an inebriated French general in Arras, Baume was extending his bachelor lifestyle. In the same manner as he had retained the widow’s thousands of pounds, he kept the medal, though he did consider giving it to a museum.

Eric Baume in the 1950s.

From the illustrative file on New Zealand writers (A–L), ref. 86-105-052, Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington

These immediate years after the war were, Baume said, the worst in his life. Mary was sicker than ever and he was fighting constantly with Ezra Norton. Finally, just before Christmas 1952, he was sacked. While he continued to fight Norton, this time for compensation, there followed a brief period of working with his brother, who had established the Baume Advertising Agency in Sydney. By his own admission Baume was ‘the most hopeless advertising man Australia had produced’, having few social graces and an inability to sweet-talk clients.21 The uniform was dispensed with and instead Baume wore a bowler hat, sported a moustache and carried a cane, believing this would help people believe he was the right man for the job. He wasn’t. He was miserable, subsisting on the £20 a week his brother paid him, and waiting for a lucky break.

It came in the shape of broadcasting, a medium in which Baume was not only to find his niche but also to pioneer the radio shock jock in Australasia. By the mid-1950s he was on air regularly on 2GB, filling two Monday to Friday programmes This I Believe and I’m on Your Side. He was abrasive as ever and often as ill-informed, offering his conservative opinions on politicians and current events. These were happy years: his fame grew, he earned good money, and Mary’s health improved marginally. He continued to write for Truth and various other papers, and became Australia’s first television news commentator on ATN7. Tapes of This I Believe were flown to the United States and broadcast to millions of people.

Fame and fortune. But despite his many admirers and detractors, and Baume’s happy conviction that he was forming opinions all over Australia and further afield, Ezra Norton lured him back to work for the Truth group, this time as director. They fought again, bitterly, particularly over the retirement of Truth newspaper in favour of the new Sunday Mirror. Even though the older, salacious newspaper had loyal readers and a history stretching back to the last decades of the nineteenth century, Norton believed he would do better with the new one. The paper, as Baume predicted, was a failure. Soon after, Norton’s health declined and the paper was sold to Rupert Murdoch. After yet another long, protracted battle with management, Baume received a lump sum to pay him out of his contract.

It was the end of his newspaper career. He had made himself into a kind of legend, not so much for his skill as a journalist or news gatherer but because of how much he had been paid. The 50s were boom times and many people were earning more than ever before, but Baume set a kind of record, earning between £12,000 and £15,000 a year.

Back on radio, Baume tried to re-establish himself with listeners. 2GB and other radio stations broadcast I’m On Your Side, but it wasn’t as popular as before. After a bout of ill health, he set himself up with a microphone in his own study at home, employing a secretary to help him with the day-to-day running of his enterprise. Audiences continued to flag, and his racist, misogynistic opinions garnered more enemies than they did supporters.

Further controversy erupted in 1963 when he was invited to West Germany and expressed praise for various aspects of the Nazi regime, particularly the Afrika Corps, whom he believed, somehow, had not been brutal. He had, in his heart, absolved them from guilt because they were not SS, the guards who manned the concentration camps. On his return Baume announced that he had experienced no anti-Semitism at all in postwar Germany.

The Jewish response was one of disgust and surprise. Wasn’t the man a Jew himself? Didn’t he care about the millions of Jews who had been murdered? Biographer Manning tries to cast some light: ‘The explanation for these apparent contradictions is that Baume is an Australian (or a New Zealander, because he refuses to make any distinction between the two countries), a monarchist, a militarist, and a Jew in roughly that order.’22 Surely sympathy for those who lost their lives in the Final Solution should not hinge particularly on whether one is or is not a Jew. It is a matter of abhorrence and horror at this extreme of institutionalised cruelty. In a restaurant in New Zealand during a 1966 tour in which he was accompanied by Manning, Baume told him that had he been born in Germany he would have been a Nazi. Perhaps he was drunk when he said this, so drunk that he forgot he was Jewish. All through his life he had a fascination with Catholicism, and would never pass up the opportunity to talk to a priest or a nun. Perhaps he longed to be able to convert, just as his mother did before her second marriage. Perhaps he wished, in some way, to be rescued from his Jewish-ness, and by expressing praise for West Germany and its recent history was experiencing again the schizoid loyalties of the cowardly bully as he had so often before.

Baume’s popularity was at an all-time low and attacks were coming from all sides. In the same year as his trip to Germany he received a phone call from James Oswin, general manager of ATN7, asking him if he would compere a new television agony/chat show, Beauty and the Beast. Baume did not hesitate. He would be the beastliest of all beasts. After a slow start, the show became enormously popular, winning large audiences in every state and city except genteel Melbourne.

New Zealand had its own version of Beauty and the Beast, with the mild-mannered and suave Selwyn Toogood as our ‘beast’. Baume was the antithesis, sometimes reducing his co-panellists to tears. These women were no shrinking violets; among them were film producer Pat Lovell (Picnic at Hanging Rock, Gallipoli), brilliant writer and broadcaster Anne Deveson, and journalist and media personality Maggie Tabberer. Baume was abusive, rude and cantankerous, but also aware that he had become in some ways a pastiche of himself, a kind of court jester. People loved to hate him.

The show ran with Baume as the beast for three years. At age 66 he received an OBE for services to journalism, which we could cynically assume he would not have received without his re-invention as a television personality. Then, as now, an identity on the box makes all the difference.

Only a year after his award, and his journey to New Zealand with his biographer – ‘Rather you than me,’ colleagues told Manning – Baume suffered another serious bout of illness. He died in April 1967.

In an obituary for Baume in the Canberra Times, Alan Fitzgerald wrote: ‘He was the strident voice in the vacuum, he was the histrionic sage dealing with the ephemeral parish pump issues of the day’, and further, he ‘doggedly echoed the prejudices of that section of the population amounting to 51%’. This could be the last word on Eric Baume, except to examine more closely the opinion he held about the differences between Australia and New Zealand. He repeatedly refused to make any distinction between the two. He saw them as the same country, despite their individual indigenous populations and vastly different colonial histories, though he often spoke ‘wistfully’ of New Zealand. It seems Aotearoa occupied a romantic place in his bifurcated heart, but his feelings were never strong enough to bring him home permanently.

Baume is perhaps not a son of New Zealand whom we’d like to reclaim, though he had his fans. On his tour with Manning he’d been frequently stopped by people who listened to him on long-range radio. A West Coast barman recognised him purely from the sound of his voice. Still, he is a colourful figure who went west and prospered. It is important to remember that he engendered love as well as fury in his many listeners and readers in both countries. Along with his more unpleasant attributes, he was generous and charismatic. Australian war correspondent Ronald Monson said of him that he ‘put his arm around the world’.23

First, a digression.

In 2014 I was invited to London to take part in a literary festival with participants drawn exclusively from New Zealand and Australia. It was a strange experience, not least because the organisers had not had the funds to run a decent publicity campaign. Audiences were small and mostly made up of expatriates. As one Australian writer remarked, we had come a very long way to talk to one another.

I was the only New Zealander in a panel discussion on ‘Lost Classics’ from our part of the world. My colleagues were impassioned and erudite – a literary critic and a publisher. Both of them had lists of books they considered Australian classics by writers such as Miles Franklin, Katharine Susannah Prichard, Henry Lawson and others. There had been a recent series of Australian classics published as ‘lost’, though surely they were all rediscovered if not really lost in the first place.

As the sole Kiwi I had thought long and hard about which books to discuss. The three I selected were The Witch’s Thorn by Ruth Park, published in 1951; Maori Girl by Noel Hilliard (1960) and Mackenzie by James McNeish, first published in 1970. Of these three, Mackenzie is possibly the least lost. It tells the story of the famous nineteenth-century Scottish sheep rustler and his dog in Otago. It is true to the period, has a big cast, and also pays tribute to the original inhabitants of the land. Writer Martin Edmond deftly describes it as ‘a work as idiosyncratic, obdurate and strange as the man it is about’.24 A television series was based on the book, which increased its popularity at the time.

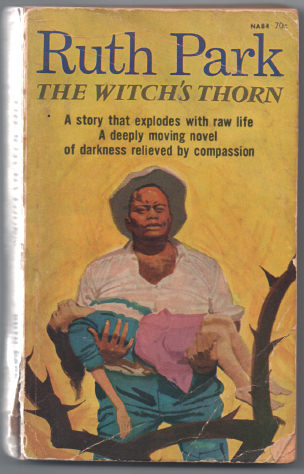

Copies of Ruth Park’s forgotten novel may still surface in second-hand bookshops and op shops. This is the Horwitz edition of 1966. The rather lurid illustration shows hero Wi carrying the child Bethany.

Maori Girl and The Witch’s Thorn are very much North Island books. Both tell stories of Māori–Pākehā relationships. Maori Girl is set in Wellington in the 1950s, and is beautifully written, with liberal use of idiomatic speech. Its author Noel Hilliard was a left-wing journalist, novelist and short-story writer. Much of his work was published in Russian. His wife, Kiriwai Mete, was introduced to him by revered poet Hone Tuwhare, and it is probably because of Hilliard’s love for her that his novel has an autobiographical, truthful feel. He went on to write sequels – Power of Joy (1965), Maori Woman (1974) and The Glory and the Dream (1978) – but they were not so well known or appreciated.

Hilliard takes as his main character Netta Samuel, one of nine children growing up in relative poverty in the Taranaki district. In her teens Netta goes to Wellington to look for work. At first she lives in a boarding house, working as the cook. It is there that she falls into bad company and has a relationship with a greasy Pākehā called Eric, who takes advantage of her innocence and naivety. Later she has a much more loving relationship with another Pākehā, Arthur, who does love her, until he finds out she’s pregnant with Eric’s child and deserts her. The novel has a tragic ending – a long time after Eric abandons her, he sees Netta drunk in a Wellington pub.

New Zealander Ruth Park was adopted by Australian literature as one of theirs. She was a famous and much-loved writer on both sides of the Tasman and further afield. Novels, children’s books and, later in life, her three volumes of autobiography were all well received. The Witch’s Thorn, written after she emigrated to Australia, is almost entirely forgotten. It has some Australian references – Kingsford Smith’s flight across the globe, and a nun called Sister Eucalyptus (Egyptus). When I found a battered copy in a second-hand bookshop, it was the first I knew of it, though I was a Ruth Park fan. There are some salient reasons for its virtual disappearance.

The story is set between the wars in a small fictitious King Country town called Te Kano, mostly populated by Irish Catholics and Māori. Central in the narrative is illegitimate child Bethell Jury, and what becomes of her after the death of her grandmother and the disappearance of her promiscuous mother. Although written in a realist style, the novel is dreamlike, nightmarish. There is grinding poverty and disastrous family relationships. People endure appalling cruelties, especially the children. Neighbour Ellen Gow lives with her husband and many children in a hovel in a sump, which is freezing cold and abounding with hellish vapours. Her main source of misery is the endless pregnancies that result from being repeatedly raped by her brutal husband. There is a German publican with incestuous desire for his daughters. A widowed Pākehā with eight children to support has turned to prostitution. Casual and deliberate racism proliferates not only among the townspeople but also authorially.

Hero Georgie Wi is so vast that when he goes to the cinema he needs two seats. Uncle Pihopa has a full moko, a cannibal past, no trousers and, it is repeated several times, lest we forget, he stinks. He believes strongly in the colour bar, not being keen on ‘Hinamen’, including Jim Joe the Chinese fruiterer. To keep warm at night, the old man sleeps in ashes from the fire. Princey, one of his relatives, worries that he’ll snack on his buttocks. There is a scene revolving around the slapstick comedy of Pihopa coming to life at his own tangi and then being killed by the shock of being dead.

It’s unfair, perhaps, to go on so much about Uncle Pihopa, when really he is a peripheral character. Mostly we move between Bethell’s miserable time staying with the Gows, her brief period given shelter by the prostitute, and her final homecoming to her loving, newly adopted father Wi, who regards her as being ‘just as good as a Maori’. In order to adopt her Wi spins a story to the local priest: he is her real father, Bethell’s mother went with Māori men, and he was one of them.

In the meantime Hoot, a Māori boy not much older than Bethell, falls in love with her. He takes her on an outing to some disused burial caves and reference is made to a tangi and the new laws introduced to stop the ceremonies going on for more than three days. There is added detail: in the past, farewells would last for so long that the deceased would start to melt through the floorboards.

Hoot knows he will have to wait until Bethell is a little older before he can court her properly. He steals one kiss and announces:

‘Now I shall be a white man.’

‘I’m not white people,’ cried Bethell passionately. ‘Aren’t we all the same underneath?’

And that, I suppose, is the nub. That is what the author wants us to take away with us, the wisdom of that time, which is that fundamentally all human beings are the same. It was a comforting notion that endured for much of the twentieth century: all peoples of the world could live in peace and harmony, the past could be forgotten and we could sense a deep human connection – the colonised absolving the manifold sins of the colonisers, the colonised offering true equality and lack of discrimination in return. The ideal was to search for what made us the same, to let bygones be bygones and look to the future, the brave new world.

The Witch’s Thorn is written with great feeling and has all of Ruth Park’s characteristic love and empathy for every character. It is an important story about the parallel suffering of second-generation Irish New Zealanders and Māori and how they got along, or didn’t. The metaphor of the title, that a person pricked by a witch’s thorn will carry the poison along to the next person, illustrates heredity and teases the notion of escape from it. Do we have to remain the people we are born to be? Can we escape deprivation and poverty?

And yes, of course, the story is racist. For a Pākehā author to create a character like Uncle Pihopa would now be unthinkable. Further, any author gaining traction in the literary world by writing about a culture not her own would be censured for cultural appropriation, viewed in some quarters as theft.

The amnesia that has banished Maori Girl and The Witch’s Thorn from our literary memories is partially the result of a well-intentioned and widespread cultural norm that discouraged non-Māori from writing about Māori. Consequently there were rafts of novels published set in New Zealand that had no Māori characters and so presented a very warped, thin notion of how we live. The few writers who attempted to write about New Zealand as we saw it, myself included, could be censured as racist for the mere fact that we included Māori characters. As recently as 2016 Waikato University history professor Nepia Mahuika told my historical fiction students that if they were not Māori then they should not create Māori characters. The students, mostly in their early twenties, accepted this cultural edict. When I responded mildly that most of my books have Māori characters, it sparked no discussion in the classroom, only an uncomfortable silence. It is as if, so many years on from the freedom that allowed Park, writing from the distance of West Island, to create a slapstick clown like Uncle Pihopa, we are not allowed to consider, create, deliberate or love Māori characters if we are not ourselves Māori. Surely this extreme position is not only ridiculous but dangerous. It is a form of mutual oppression.

In the nineteenth century, European writers could believe that they were giving voices to people who had none. Throughout the twentieth century indigenous writers around the world published excellent novels, and arising alongside that great upswelling of voices was this notion that we could only write about who we were. Imagination, like God, lost its vigour. It was a dangerous idea for a man to imagine how a woman thought or for a heterosexual to imagine homosexuality, even though the practice of writing from opposing points of view had long been a method of fostering understanding.

I suggested, in that talk in London, that these lost classics should not remain lost. I wondered if we would at last reach a stage of cultural maturity where we could look back at these very flawed mid-century Pākehā attempts to spin stories that expressed love and respect for Māori, and if in the process we could forgive those novels for their ham-fisted, often inadvertent prejudice. In the audience was a young woman who tweeted: ‘Stephanie Johnson says we should read racist books.’

What a dangerous thing is instant publication. I did not suggest that we should read ‘racist books’ but rather books from our heritage that do not necessarily fit with current sensitivities. There is much in both novels to upset us, it is true, but also much to delight and fill us with pride. Ruth Park and Noel Hilliard were remembered by those who knew them as people of principle. They did their best. We could not say that, with any conscience, of Eric Baume.

Half-Caste, written in Sydney in 1932–33, precedes the others by around 20 years. It wrestles clumsily with the idea of racial inheritance.

The novel opens by introducing us to a newly arrived Scotsman in Auckland, Peter Wade, who is getting ready to go to the opera. ‘He rather hoped to find Maori in a primitive state.’25At this early point of his arrival he has not met any. The invitation to the opera has come from a mysterious older woman, who is attending the theatre with her young companion Ngaire Trevithick, who has dark brown eyes and golden hair. When Wade later dines with benefactor Helene and Ngaire at their home in Mount Albert, he meets their Persian-cross cat. He holds forth: ‘Marvellous thing about animals – you put two breeds together and form a third breed which may be more valuable than either of the original strains. The superiority is often recognized. Now if only man were so perceptive where different breeds of humans were concerned, it might end a lot of the world’s troubles, what? But we’re all so dense. Must keep to our pure strains. Can’t let the master race get contaminated …’26

Ngaire’s appetite for her dinner evaporates and Wade, because he doesn’t understand that she is the half-caste of the title, is confused. She becomes quiet and sad, and when Helene hears her crying alone in her bed that night she mutters to herself, ‘Damn the girl. He’s a fine man. Why can’t she forget she’s half-Maori?’27 The implication is that Ngaire is so ashamed of her Māori blood she can’t establish a relationship with a Scotsman, despite the fact that at this time in our history thousands of people claimed combined Caledonian and Māori heritage.

The third chapter abandons the established narrative and plunges into a history lesson: ‘Over a century before the first Spanish galleons ventured westward from the Azores, Chief Marutuahu rolled his fleet of war canoes down to the Tahitian shores and set sail with his tribe across two thousand miles of the Pacific into the south-west towards New Zealand.’28 A few pages later Baume arrives at the land wars of the 1860s:

For twenty years the Maori courage held out against the British musket until the warriors were so decimated that further resistance was impossible. Their courage won them the right to a portion of their former lands and representation in the government established by the conquerors … So to survive, the Maori withdrew to the lands that remained to them, clung tenaciously to the ways of their fathers, and the two peoples were divided. Such divisions do not last. Where a society as a unit draws a line, the individual member of the society will cross it.29

The individual member, in this case, is Ngaire Trevithick. The narrative then returns to her, rolling back the years to her mother Rewa and a sailor from Liverpool, and the conception of Ngaire on a beach. A German doctor visiting the mother and new baby finds ‘Rewa reclining on her cot inside the shack surrounded by a group of pipe-smoking, babbling women. In the semi-darkness was the rancid smell of perspiration mixed with the fumes of the drying shark, which hung from the rafters. Women entering the room for the first time paused to rub noses with the mother before accepting a puff from the ceremonial pipe … He smiled at Rewa, and her coffee-brown face smiled back, the tension of her full lips bringing the blue tattoo marks on her lips into bright relief.30

It is possible that during his time on the Waipa Post Baume travelled to the Kawhia district, which is where he imagines Rewa lives. It is also possible that he was a guest in a kāinga and that his nose was offended by drying shark, but it is unlikely that the fish was dried inside a whare. Also, although Māori adopted tobacco use with tragic results, and would often share pipes, smoking was never ‘ceremonial’.

Rewa tells the doctor of the conception, making the other women uncomfortable because she is the daughter of the chief, ‘a descendant of Te Kooti’. But Rewa has had the benefit of an English-style education and ‘mortifies tourists’ by quoting Chaucer and Shakespeare: ‘Her education was her captive, a thing she had wrung from a conquering race and she loved to parade it publicly. If she sometimes chanted lines of Shakespeare at a tribal celebration it wasn’t so much from love of Shakespeare as from her joy at making England’s greatest poet the servant of a Maori girl.’31

After the doctor leaves, Rewa looks at her pale baby: ‘There is more in life than the dominance of a Maori bull. It is only the colour of the skin that makes the difference.’32 Here again, appallingly expressed, is the sentiment Ruth Park approached – that we are all the same, that there is no cause for worry about the things that make us different. The aim is homogeneity.

When the narrative returns to Auckland in the early 30s, Ngaire and Peter Wade are driving out of town in Helene’s Bentley, Ngaire behind the wheel. They put the roof down, smoke cigarettes, drive ‘westward along the isthmus then north again through the rolling pasture lands until they were back along the coast’. Ngaire has gone to an Anglican school in Auckland, possibly based on Diocesan School for Girls. They talk about religion. Peter says:

‘As soon as a man admits there may be more than one correct way to worship God, he weakens his own belief … when you ask a man to be tolerant of other beliefs, you’re merely asking him to give up his own.’

‘Then you don’t believe in tolerance?’

He smiled at her, ‘I hope I don’t impress you that way. I believe in it very much, but I think people ought to know what it means.’33

This was the great Pākehā fear of the time. If you give an inch, you will lose a mile. Tolerance is all very well, but only one way – the way that maintains the status quo.

Back at the pā Ngaire has a close friend, Paul, who gave up studying for the ministry after three years because a night on the whisky made the page blur and he saw instead ‘the beautiful brown faces of the girls at home, the girls who fall into your arms when you are ready for them. So I killed the Pakeha’s god too lest he spoil the beautiful girls when I brought him among them.’34

This paragraph owes more to the author’s smutty ideas about dusky maidens than anything else, ideas that may well have been urged on by American anthropologist Margaret Mead’s 1928 book Coming of Age in Samoa. It’s doubtful Baume would have read Mead’s book, but he would have heard about her portrayal of Polynesian sexual behaviour, a portrayal later proved false by New Zealand anthropologist Derek Freeman.

Ngaire has rejected her faithful friend Paul thanks to the influences exerted by her private girls’ school. She thinks he is dirty, whereas she recognises ‘the value of clean clothing and a clean body, of polished nails and good manners’.35 The reader is expected to accept her apparent opinion that no Māori has these attributes. She wonders how she can possibly tell her admirer, ‘I’m a bastard, Peter. A half-breed bastard who was suckled by a woman with a tattooed face. My father was a drunken bum …’36

She writes to the German doctor and asks him what to do. Doctor Sembach thinks ‘… you would love to go to Scotland where ze Maori do not live – there ze past would disappear and never trouble you again … In Scotland ze gorse is yellow and like New Zealand smells ze same.’37 The attempt at writing a German accent is mirrored throughout by an insulting idea of how Māori spoke.

Meanwhile, Paul is dying. He wants Ngaire never to visit the pā again – he loves her and hates seeing her suffer as she does there. He tells Sembach not to let her know he’s dying and to keep her away from his tangi, so Sembach goes to visit Ngaire after not seeing her for four years. He delivers a letter from Paul saying her inheritance is all gone because he spent it. ‘Thus the Maori take vengeance on strangers who spring up like parasites in our midst.’

Ngaire is aware that her failure to tell Peter about her heritage is wrong because if they have a child it could be ‘dark-skinned, thick-lipped offspring [who] would suddenly make one or both of them subject to the cruel laughter and probably ostracism by the society in which they had been raised’.38 To put some flesh on the bones of this idea, we learn in reportage about Ngaire’s experiences when she left school. She tells Peter about how she went to live with a Pākehā family, the Mercers. The father is a judge and the mother cold-hearted. While she lived with them she met up again with Robert Treacy, a racist snob who had earlier tried to rape her. For some unfathomable reason they become friends and she falls half in love with him. Mrs Mercer tells Ngaire she has to leave the home and get a job, but when the judge won’t help her find work she turns to Treacy, who gets his own back for not succeeding in raping her. He says he has only been taking her out to get in with the judge, that he’ll only help her if she’s his mistress. In true melodramatic fashion, she becomes Mercer’s maid for four months, hiding in the house.

Peter is appalled and says, ‘… he treated you as though you were some native girl’. Still Ngaire cannot tell him the truth of her heritage. But Peter asks her to marry him, and she wonders if his earlier remark came because ‘habitual domination has led to habitual contempt’.39

She accepts his proposal, and Helene, delighted, tells her that she’s bequeathing Ngaire her entire estate. The wedding is arranged and takes place at ‘a little vine-covered Methodist church’. All the guests are Pākehā – the German doctor has informed the Māori relatives, including long-suffering Bella, that they cannot come. Bella shows up anyway:

There had been a gasp as an old woman started to her feet and tried to draw back out of sight. She was much too slow. She stood there not ten feet from them in a loose denim dress, her large eyes red-rimmed from weeping, her tattooed lips drooping open, and the whole head framed in the red handkerchief tied about it. It was Bella. Ngaire fainted.40

After the wedding reception Sembach tells Ngaire she’s in good hands now and should not worry that Bella had come uninvited:

Ngaire … laughed again and her eyes were hard and glistening. Sembach didn’t like it, but there was nothing he could do in the short period of time left to him. Nothing at all … For the first time in his long active life he realized that racial problems were not racial problems at all. They were thousands of individual problems which looked like a single unit only because those who studied them insisted upon seeing them that way. But the solution remained an individual solution for each person concerned.41

The not very happy couple honeymoon in the South Island, then return to the north, where they stay in a Rotorua hotel. Who should be there at the same time but the dastardly Treacy. By unspoken mutual agreement Ngaire and Treacy pretend they’ve never met. Ngaire observes that the two men ‘had a bond between them – the white man’s bond which was so much of the white man’s environment that most of them never knew of its existence’.42 But the moment she is alone with Treacy he tells her, ‘It seems you’ve married this very eligible young man without telling him that your children are apt to be piccaninnies.’43

Later, she goes to Treacy’s hotel room to strike a bargain that he won’t tell Peter about her Māori heritage. Of course he wants sex. Luckily, there is a conveniently loaded gun lying on the desk, so she shoots him. The body is not discovered before she and Peter leave for Auckland to board the ship to Scotland. Somewhere beyond the Gulf, Ngaire chucks the key to Treacy’s room overboard. She is unhappy and suffering from nausea – she is expecting a baby.

When the ship docks in San Francisco Ngaire asks to wander about by herself. Straight away she goes to Pan-American Airways and buys a ticket back to New Zealand. She leaves a note in the hotel for Peter: ‘If I bring you pain now, it is as nothing compared with the pain I would bring if I remained beside you.’44 Back in Auckland Ngaire goes to Helene. She tells her, ‘You think I’ve lost my mind but you don’t want to say so to my face. But I haven’t lost my mind, Helene. If anything, I’ve found it.’45 She believes the only reason Helene ever loved her was because she could see that Ngaire was a criminal, and Helene had had practice at loving criminals, having once been married to one.

What, asks the bewildered reader, was her crime before she shot the would-be rapist? Is Baume suggesting that her crime is her mixed heritage, or her concealment of it? She explains to Helene: ‘I’m just telling you why you loved me – because deep inside your white soul, so deep that even you have forgotten about it, is the feeling that it’s morally and ethically wrong to be anything but white.’46 To justify killing Treacy she says, ‘He needed to be killed simply because he was a white man who thought he had rights over me because I was of another race. That is always sufficient reason for a Maori to kill a white man … but I killed him because I was a white woman trying to hide a criminal past. Now I’m not a white woman any more. I’m Maori. Only by being Maori can I excuse myself. It’s the only way I’ll find peace.’47

So saying, she returns to Bella and the village.

When the jilted Scotsman follows his wife’s trail back to Auckland he is met by the German doctor, who tells him the truth of Ngaire’s parentage. Peter is taken aback. ‘Damn it, she’s a Maori, not a negress!’ Sembach asks him what he would say if she was a negress and Peter assures him he wouldn’t care. Together they travel to Ngaire’s village, only to find that she has committed suicide, leaving a note:

Darling Peter,

Sembach says you are coming, and if you come you will know why I went away from you. For a time I thought I might stay here until our child was born – hoping things would be different for me then. But now I know they will never change. I am not for the Maori. But I am not for your people either. I tried so hard and failed. Forgive me Peter, please, please forgive me. If you need to know more, talk to Helene. Only know that I could not have seen you without going away with you again, and to do that would be to kill us both ... I shall die with your name on my lips,

Ngaire48

Baume wrote two different endings for the book. In the 1933 edition, Ngaire does not commit suicide. When Peter arrives at the village the baby has been born and Ngaire greets him warmly because the baby has blue eyes! He forgives her for running away, and for the truth of her lineage.

The novel is still available today in rare-book sections of libraries and, more surprisingly, also as an ebook. On the Harlequin Romance website it is listed as general fiction, and described, with capitals, as ‘Clean and Wholesome’.

As recently as 2015 Half-Caste received attention from Kirstine Moffatt in her essay ‘What is in the blood will come out: Belonging, expulsion and the New Zealand settler home’ in Jessie Weston’s Ko Meri. Comparing Baume’s novel to Weston’s nineteenth-century novel, in which the bi-racial heroine also dies, Moffatt remarks that ‘anxieties about the “taint” of Māori blood and the atavistic power of Māori heritage continued well into the twentieth century. In Eric Baume’s Half-Caste, Ngaire Trevithick is alienated from her Maori community by virtue of her pale skin and European education … The novelists who create these characters fear the Maori “other” so much that they reject assimilation in favour of expulsion and, in many cases, annihilation. The death of these heroines symbolizes the death of the race.’49

Tastes in novels change generation by generation, and we are seeing in our time a blurring between the once great divide between literary and commercial fiction. Broadly, commercial fiction relies heavily on story, whereas literary fiction may be more concerned with style and the manner of telling. Literary fiction may challenge contemporary mores and shibboleths, while commercial fiction may not. Clumsily told, Half-Caste is so rich in story that it verges on melodrama. Most certainly it reinforces the common prejudices and opinions of its time.