1951 is the sixth year of peace following the end of World War II, and Australia is experiencing a boom time. Wool shorn from the backs of Australian sheep is manufactured into uniforms, mittens and balaclavas for American soldiers fighting in Korea, with the result that sheep farmers’ yearly incomes have quintupled – they are buying cars and radios, fine clothes and furniture. Inflation is galloping and Prime Minister Menzies is trying to control it by introducing taxes. His budget this year will target Holden dealers, razor blades, shaving cream, ice cream and sweets, among other commodities deemed luxuries.

In view of growing international concern about communism, he introduces the Communist Party Dissolution Act. A referendum is held in September on the issue and Menzies is defeated by 50,000 votes.

The cost of the Snowy Mountains Scheme, designed to provide both hydroelectricity and irrigation from the Murray and Murrumbidgee rivers, has blown out from its original cost of £65 million to more than £200 million. Construction goes ahead, drawing men from all over Australia. Many of the workers are new immigrants, who may now become new citizens of the new nation. Two years ago, Australia Day 1949 marked the beginning of Australian citizenship.

Holden is in its third year of manufacturing on Australian soil what have rapidly become iconographic Australian cars; cricketer Don Bradman is the most famous and revered sportsman ever; and shopping and consumption are the new norms. The beer keg has become a regular fixture at parties, a focal point for the men otherwise booted out of pubs at six o’clock. Parties are divided by gender: while the men honk back the beer, the women gather in the kitchen, in keeping with the widespread idea that women who willingly consort with the men are loose. Nonetheless, hems are up, bathing suits are smaller and beach-culture is taking hold.

Douglas Stewart is the father of a three-year-old daughter and in his second decade as editor of the Bulletin’s ‘Red Page’. The magazine is enormously popular and he is besieged with copy for his small literary section. For business and pleasure he conducts correspondence with many writers on both sides of the Tasman. He will later remark that this period was a ‘tremendously exciting time. We did feel that we were at the centre of the movement of Australian culture at that time. There wasn’t much else ... Southerly and Meanjin were only just starting … I had absolute freedom and because the writers too recognised it as the centre, the only place they could get published, we met everybody who was worth knowing and tremendous people just used to walk in the door. I remember seeing Miles Franklin and Mary Gilmore one day appear like a couple of giantesses or goddesses or something in the doorway.’1

Eric Baume is back in Sydney but possibly estranged from his long-suffering wife. There is a period soon after his return during which he lives alone in Kirribilli before going back to the family home in Gordon. Every day he travels into the city to the Truth office, where he writes, edits, and fights with manager Ezra Norton. It is a time of adjustment for him as he recovers from the great excitement of the war and intervening travel to Berlin, France and the United States.

For Roland Wakelin 1951 is a positive, productive and possibly nostalgic year. He takes a position teaching at the National Gallery School, Melbourne, and his work is represented in the prestigious Jubilee Exhibition of Australian Art with the inclusion of ‘The Bridge from North Sydney, 1939’. In December he and his wife will travel to New Zealand, staying for three months and visiting his brother in Wellington. It is the only visit he makes to the land of his birth.

Dulcie Deamer is 51 years old but living life with the enthusiasm of a teenager looking forward always to the next party. It is 11 years since she had a novel published, which is not to say that her output has slowed. She writes on with fervour, surviving on next to nothing. As her daughter Rosemary will recall, Dulcie stays in bed until late each day, ‘writing for her own pleasure’. She is also spending a lot of time delving into the occult with her exciting new New Zealand friend Rosaleen Norton.

For Jean Devanny, 1951 is the year she consolidates her attachment to Queensland, a part of Australia in which she has travelled and worked since the 1930s. Not only does she publish her popular Travels in North Queensland but she also buys a cottage at 2 Castling Street, Townsville, for £650. It will be her first true home, the only house she ever owns, and she will live there until her death in 1962.

‘In human and animal alike only tameness bores.’2

When reading Jean Devanny’s novels or non-fiction, her autobiography, Carole Ferrier’s excellent biography, or commentary from other sources, it is easy to experience a surprising, niggling envy for her life and times. Surprising, also, because Devanny’s life was in many respects tragic.

The first source of this envy is for the conviction, passion and energy that fuelled Devanny’s position at the vanguard of twentieth-century feminism and left-wing thought. The second is for the articulate love and knowledge she movingly expresses for the natural world. Her non-fiction works By Tropic Sea and Jungle and Travels in North Queensland are much neglected and deserve a renaissance, if only to remind us of what we have so far lost and stand to lose in the near future.

Of the five West Islanders, Devanny was the only one to eventually make her home outside Sydney. Many New Zealanders fall in love with that city and never go further afield. Others, like Devanny, formed a more ambivalent relationship with it. Her connection with Queensland began in the 1930s when she travelled far and wide throughout the state on exhausting speaking tours for the Communist Party of Australia, the CPA. She had grown up in rural, verdant Golden Bay at the tip of the South Island and her affection sprang partly from what she perceives as a similarity: ‘I was greatly taken with the type and calibre of these people. The mountainous country resembled my homeland, and developed like characteristics in the natives. North Queenslanders were soft of mien; and in general they were kind and generous.’3 She was to retain this love for the north of Queensland all her life.

By 1951 the Devannys had been in New South Wales for 22 years. It was August 1929 when the family first arrived in Sydney, at the end of a decade in which newspaper Truth described the city as a ‘mecca for magsmen’. Depression was biting and crime was rife.

Devanny was to recall not only how the ‘midday heat had us in a lather of perspiration’ but also how she and her family

‘marvelled to find Sydneysiders so “foreign” … Many of the social aspects of Sydney shocked us. For instance, the ramifications of the White Australia Policy. All enlightened New Zealanders of my generation detested the White Australia Policy. The teaching of pride in, and respect for, our native people the Maoris was part of the school curriculum … the New Zealand Labour Movement had reflected this feeling. It had officially pronounced the WAP to be a nefarious and reactionary doctrine … [we were] shocked and confounded … to find the theory expanded to include South Europeans!’4

New Zealanders are often accused of propagating the utopian myth that eulogises New Zealand race relations. In that light, Devanny has been roundly criticised for this statement, sometimes unfairly. While it is true that many New Zealanders had no understanding of Māori culture, let alone respect for or pride in their indigenous people, it is also true that a superficial identification with tangata whenua was common. In rural areas, such as the one Devanny knew, Māori were more integrated with new populations than they were in the cities, where they were almost invisible. It is important to note that by the time of her arrival in Sydney, Devanny had earned applause for her treatment of Māori characters in her novels, in particular Jimmy Tutaki in The Butcher Shop and Rangi Fell in Bushman Burke.

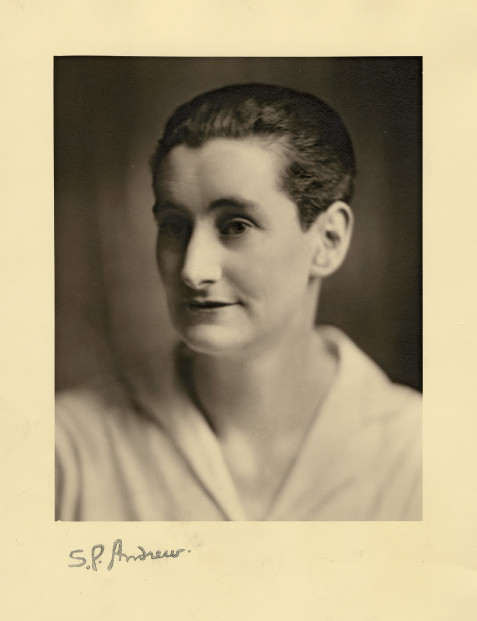

Jean Devanny, c. late 1920s.

S.P. Andrew photographer, Box-074-002, Hocken Collections – Uare Taoka o Hākena,

University of Otago

But although in many ways a successful and sympathetic character, Jimmy Tutaki illustrates Devanny’s confusion about Māori, particularly when it comes to sex. He is as knowledgeable about English literature as his Pākehā employers and attended the same school as his Pākehā contemporary Barry Messenger. He has high standing in his own community and seems to be well versed in Māoritanga. However, once Miette begins pursuing him, Devanny tells us he is ‘only a few decades removed from the savage’ and so is unable to resist a white woman of low character who makes herself available.

Bushman Burke was also known as Taipo, the nickname Devanny gives her central character. Devanny believed the word meant wētā, an insect native to New Zealand, but it is also a transliteration of ‘typoid’, and may mean a kind of supernatural being. Whatever, the novel is less about him than it is about Flo, the flapper who marries him for his inheritance. Flo’s father Wallace is a well-off divorce lawyer with a reputation for being on the side of wronged wives. Taipo is caught in Flo’s glittering thrall despite his preference for women who don’t smoke, drink or wear cosmetics. He is fully aware that she does not love him and is marrying him for his money. Flo has an ongoing affair with Rangi Fell, whose mother is Māori. Unlike Taipo, Rangi can recite poetry, jazz (i.e. dance) beautifully, and sing. Rangi functions as the villain of the novel, interested in Flo only for sex and a good time.

Flo treats Taipo very badly. While she tries and fails to turn him into a city man, she is rude, cold and hypercritical. On her insistence he has tennis lessons and learns to dance, but disaster looms: he finds out about her affair with Rangi. Immediately he returns to his bush home on the West Coast. Flo follows him, and in keeping with many of Devanny’s heroines, undergoes an epiphany and becomes the woman she should be. The novel ends as Flo falls in love with Taipo properly.

Bushman Burke was Devanny’s seventh book, and the second to last novel she would set in New Zealand. The people and landscape of Queensland would forever replace the southern country as the landscape of her imagination.

Within the first year of their arrival in Sydney, the Devannys had joined the Communist Party. The party had by now aligned itself firmly with the Soviet Union, which meant that it was more concerned with policies that would suit that faraway monolith, rather than any vision of a communist Australia. Jean Devanny embraced the party with all the fervour of the newly converted. Neither the New Zealand Labour Party nor the Australian Labor Party was left leaning enough for her; both had been a source of disappointment.

The Devannys’ misconception that the Depression was less severe in Australia than it was at home was very quickly corrected. The family moved from slum dwelling to slum dwelling between Surry Hills and Wolloomooloo. Work was hard to come by. Karl was deadly ill and Hal was unemployed. Jean had no choice but to forget about her writing. In 1930, desperate to support her family, she left the city far behind to work on a sheep station in the northwest of New South Wales. She had been offered a job as a ‘general’ for a squatter. She was paid £2 a week and lasted only a few months – as long as she could stand. She recalled, ‘The train journey out shook me badly. The consuming and over-all impression I gained was that here was a land at once in its forming time and decayed, worn out.’5 It was her first journey into the bush, so different from the countryside of her homeland, and it served to whet her appetite for it. The people too fascinated her. The hard lives endured by the tough inhabitants of this part of her new land inspired her first Australian novel, Out of Such Fires, which was published in New York in 1934. It was never to be published in England, banned for its outspoken disregard for organised religion.

It is perhaps worth remembering here that the banning of The Butcher Shop in Australia in 1929, the year of Devanny’s arrival, may have been less due to its content than to Devanny’s readiness to invite trouble. Not long in Sydney, she gave a talk at the Aeolian Hall on ‘Literature and Morality’ and the perils of government-sanctioned censorship. She had ‘put her head above the parapet, where it was noticed by authorities’.6

Back in Sydney she continued her political work. The Communist Party found the means to provide her with a small stipend, enough to meet her costs and a little left over for the family. One of her first actions was to help organise a mass meeting of unemployed women at the town hall. When the throng, led by men and containing all of the Devannys, marched to Parliament House, they were met by the police, who promptly arrested them all. ‘That my whole family were in jail together was reckoned a record for the revolutionary Labour Movement,’ noted Devanny dryly.7

One of the aims of the meeting was to involve more women in the movement: ‘Significant of the difference in cultural standards between Australia and New Zealand was the complete absence of women at many of my meetings,’ she wrote. ‘In my homeland, women were the half of every political gathering. Here – a sprinkling appeared in the halls of the FOSU [Friends of the Soviet Union] and the Party … gradually the women turned up. We were soon getting meetings of women only.’8 Although Devanny was never to call herself a feminist, women’s issues consumed her more than any other. In 1930 she worked also for Mrs Piddington’s birth control clinic in Martin Place, an association that has led to her being accused of eugenicism.

It is true that early feminist movements advocating reliable birth control, which improved the lives of women, were linked with eugenics, but not all women espoused the most extreme aspects of the theory. Women from the left and right of the political spectrum are often uncomfortable bedmates on feminist issues. Devanny’s writing displays great compassion and understanding for those who would be persecuted or dispensed with under a eugenicist regime, as would be demonstrated in the near future by the persecution of non-Aryans in Nazi Germany.

Political conviction and a newly contracted travel bug combined to send Devanny off to the world congress of Workers International Relief (WIR) scheduled to take place in October 1931 in Berlin. She left Sydney in August, all expenses paid by the Australian Communist Party, on the Nordeutscher-Lloyd freighter Murla. When the ship stopped at Fremantle she travelled up to Greenmount, an hour and a half by train from Perth, to meet Katharine Susannah Prichard, an author she hugely admired and a founding member of the Australian Communist Party. Jean would undoubtedly have read Prichard’s most enduring novel, Coonardoo: The well in the shadow (1929), which centres on an Aboriginal woman on a farm in Western Australia.

To read Coonardoo now is to marvel not only at the quality of the writing but also at Prichard’s empathy and understanding of Aboriginal people at a time that was, after all, only a year after the Coniston massacre in the Northern Territory. This was the last recorded officially sanctioned mass murder of indigenous Australians – men, women and children. Few people of European descent felt or expressed concern for Aboriginals’ continued survival, let alone their wellbeing. But just as Eleanor Dark’s The Timeless Land did in 1941, Coonardoo answered an overdue curiosity. We may quibble and disparage these attempts now, in the twenty-first century, while a renaissance of true Aboriginal literature, written and performed by indigenous authors and playwrights, is flowering. Lawyer, writer and academic Professor Larissa Behrendt deems Coonardoo to be ‘about white sorrow, not black empowerment. The book leaves out any possibility that Coonardoo and her community could benefit from the assertion of their own authority or autonomy.’9 But if we are to judge these books by the standards of the time, Katharine Susannah Prichard and Eleanor Dark, and particularly the former, were trailblazers.

Devanny and Prichard spent two pleasurable days together walking in the country and talking about literature and politics. They differed in their opinions of D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Prichard, whose work was greatly influenced by Lawrence, loved it; Devanny did not. She commented later that Prichard’s ‘personality I found to be in marked contrast with my own. Her manner was quiet and serene, her expression deeply thoughtful, if not grave … I joyed in the literary discussion and interchange of opinion and ideas.’10 Years later, Prichard wrote in a letter to a friend: ‘Jean Devanny is wonderful. No one I know is so vital, magnetic, absolutely devoted and disinterested. She is a great woman, really. I wish I could give all my time to Party work as she does.’11 She and Devanny were to become firm friends, though the relationship was tested, wavered and crashed, never to recover, in the late 1940s.

Devanny set sail for Europe. To pass the time on the voyage she wrote what would be her last novel set in New Zealand, Poor Swine. The story is set in Granity, a mining village on the West Coast of the South Island. By now her literary style was well established into her trademark combination of romance, sometimes cloying and even histrionic, combined with socialism, sometimes didactic. It was not a particularly winning formula, and Poor Swine had a hard time of it, published only after deliberation by the authorities on whether it should be banned. There was a moral concern: the central character is a married woman who enjoys the attention of more than one lover without any detectable authorial censure.

Sex appears to have been on Devanny’s mind in Europe too. From Berlin she was invited to travel to the Soviet Union, and on her return to Australia she would regale her audiences with the vision of a muscle-bound agricultural worker she had seen in a wheat field. On one famous occasion, having described this Adonis, she informed her astonished listeners that ‘sex was a delightful experience in the Soviet Union’.12 At a Waterside Workers’ Federation meeting, where we can assume that most of the attendees were men, she repeated the sentiment. A voice from the back called out, ‘It’s not too bloody bad here either, lady.’13

It seems that back in Australia more jokes were told about her possible sexual exploits in the Soviet Union than her political activities. Despite Hal’s revolutionary ideas, he must have been embarrassed by these stories of Jean’s Red Guards and Russians with rippling muscles. The couple had been miserable for some time. Jean dates their first separation – there would be several – to the day of her arrival back in Sydney. ‘From [that] day … my relationship with my husband was fundamentally changed. By mutual agreement, each from then on was absolved from marital obligations.’14 They may have ceased their sexual relationship, but for almost all of their lives they remained financially and emotionally dependent on one another.

Devanny’s work for the party redoubled on her return. The visit to the Soviet Union inspired the establishment of WIR art and theatre clubs in Sydney. Artists who were not necessarily sympathetic to communism but interested in social realism formed a splinter group, which they named the Workers’ Art Club. Devanny remained associated with the group, seeing it as a broad-front organisation and a way to garner interest and support for workers’ rights. This did not please the party, which wanted the working class to be united inside the Communist Party only. She was forced to leave the WIR, and endured further criticism from the entirely male secretariat for her publicly expressed views on birth control and the party’s lack of regard for the contribution made by women. Her daughter Pat Hurd believed that Devanny was so upset by this that in March 1933 she was dangerously ‘close to having a breakdown’.15

Drusilla Modjeska comments that Devanny ‘never called herself a feminist with its bourgeois connotations and accepted without question that under socialism the “woman question” would cease to exist’.16 She was to discover, as many women have since, that if a man has left-leaning politics it will not necessarily make him a champion of women’s causes. As late as 1985 New Zealand feminist scholar Lynley Cvitanovich was asking: ‘What does it mean in the nineteen eighties to be a man and a socialist and what might commitment to socialist politics mean for personal relationships with women? Do men continue to fit women unproblematically into the categories of Marxist analysis and how might we deal with this as socialist women?’ Cvitanovich remarks, ‘Jean Devanny was one of the first in New Zealand to begin grappling with these kinds of issues.’17 She then goes on to describe a ‘national gathering of socialist activists’ in the 1980s which is ripe for satire:

In the background the cooking and the kitchen jobs still get done. There is a man in charge and there are no complaints. His helpers are both men and women. You need to look especially closely though to see how things are running. It is the men who wander in and chop and slice ‘real’ political issues and a few onions. Shortly they meander off. The women wander in too. They chop and slice and peel and stir. Hours later they are still there. Not such an easy thing for them to simply pass in and out and consider they have done their bit. Like Val Devoy in the novel (Dawn Beloved) these men give women’s needs only lip service. Ultimately domestic concerns are assumed to be inseparable from women’s concerns.18

Had Devanny witnessed the scene above, it is probable that she would have seen nothing amiss. It was normal then, as it mostly continues to be, for women to bear the domestic burden. Women of the early twentieth century who managed, as Virginia Woolf famously said, to ‘kill the angel in the house’, were the ones most likely to achieve ‘a room of one’s own’, as Katherine Mansfield did. These women were rarely from the working class. In Devanny’s circle of women writer friends, all were better cushioned than she was. Katharine Susannah Prichard, whose husband had tragically committed suicide, was middle class, and had her own home. Eleanor Dark’s husband was a doctor. Miles Franklin, although she endured poverty at the end of her life, was a successful writer with an income for most of it. Marjorie Barnard was university educated, held various white-collar jobs and maintained a sense of security by remaining in the family home with her elderly mother, whom she looked after. Devanny was dependent on a stipend from the Communist Party of Australia which, despite its many criticisms of her, certainly got its money’s worth.

Devanny’s long-running affair with J.B. Miles, the party’s general secretary, began on her return from the Soviet Union. She never names him in her autobiography; instead she calls him Leader. In keeping with all of her relationships, the affair was extremely tumultuous. She was a woman of great, stormy, conflicting emotions, who had the knack of annoying even her closest friends, but once she had made a decision to pledge her allegiance, that loyalty was set in stone. For the most part she writes of Leader with worshipful respect, at least until he turned against her, as many in the party would later do. But for now he was as thrilled as she was to be engaging in a secret love affair.

Physically, Miles was unprepossessing. Probably shorter than Devanny, who was tall and thin, he had a noticeably big head and short limbs. He was also married, with five children. There was a level of delusion in the couple’s conviction that nobody knew about the affair. Gossip was rife, and as Devanny herself was never blessed with any degree of discretion, more people knew about the relationship than the lovers thought. She and Miles would talk and argue deep into the night. And of course, among the many things they disagreed on were women’s issues, or at least the degree to which women should be liberated, or even listened to.

Devanny’s love for Miles was inextricably tied up with her devotion to communist ideals. Communism for many thinkers and writers of the time had the fire and soul of a religion. It was embraced with righteous fervour. For Devanny, sleeping with Miles could have been a little like sleeping with the high priest. Through him came all communications from the Soviet Union; through him came the invitation to attend the world congress of Workers International Relief in the first place. He had recognised Devanny’s power as a public speaker; he had heard her argue with many of the members of the party on various issues. Early in their association, at least, he had great respect for her and recognised her as a valuable asset to the party.

In the two years following the trip to Europe and the USSR, Devanny worked tirelessly for the party, travelling to Melbourne on a speaking tour and addressing crowds of tens of thousands in the Sydney Domain. On one occasion the police lifted the platform and tipped it up to get her off. When a riot erupted she was dragged away and put into a nearby lock-up. Hal Devanny took her place and carried on speaking over the turmoil. Consequently Jean was sentenced to three months jail or a fine of £30 for resisting arrest and assaulting the police. With her characteristic fiery lack of self-control she told the court, ‘I don’t deny that I kicked him! I’d do it again!’19 Fortunately, International Class-War Prisoners’ Aid paid up, as a fine that size could have broken the family finances. The Devannys were barely staying afloat, moving from one miserable slum to another, and all the time anxious about Karl’s health.

Somehow, with the prodigious energy that so many people who knew her would comment on, Devanny managed in 1932 and 33 to write two more novels, The Ghost Wife and The Virtuous Courtesan. Neither book has much literary merit. Each in its way caused a scandal. Just as Devanny was forced by her circumstances to work harder than anyone else, she was also forced to write for what she imagined was the marketplace. Her good friend Kay Brown, whom Devanny would later say was closer to her than a daughter, remembered her buying two cartons of cigarettes and hiding out in a secret room in the Cross so she could bang out these steamy tales. Brown would bring her food and not divulge the address to a living soul.

So scandalous was The Virtuous Courtesan, it was not allowed into Australia until 1958, 23 years after its New York publication in 1935. Not only does it contain gay and lesbian characters, it also portrays heavy drinking among the middle class and a working-class girl who is sold into prostitution at the age of 10. Another character carries out a do-it-yourself abortion with a knitting needle. The question Devanny seems to ask is whether marriage is a form of legalised prostitution no better or worse than the illegal version. This is an issue that dominated feminist discussion well into the late twentieth century.

In 1934 Devanny travelled to Queensland for the first time, little realising that the northeastern state would become not only the setting for some of her most successful novels, but also, eventually, her home. There were many trials and tribulations to be got through in the interim, as well as a bereavement from which she never quite recovered.

For a long time Devanny had suffered from a gynaecological problem, which would worsen with the onset of menopause. In her correspondence with Miles Franklin she recalls an operation that she had in the 1940s to remove ‘ten pounds of malignant growth’ and treatment for an ‘ulcerated vagina’.20 Diagnosis was still sometime in the future. Now, she was 40 years of age, extremely anxious about her son’s health, exhausted, thin and frantic. On the one hand the party was happy to release her from her punishing schedule for a period of convalescence, but on the other charged her with setting up a branch in Cairns. She was a stroppy, unwell woman travelling alone, with little idea of how to look after herself. At least for part of the time she had Kay Brown with her. Pat Hurd, in her contribution to her mother’s autobiography, recalls that a Mount Isa audience on that first tour was antagonistic because both women were wearing slacks and Devanny was known to be from New Zealand: ‘Someone called out “What can you know about Australia? We don’t want to listen to you.” Devanny replied: “I know this much about Australians, they all wear wrist watches and call each other bastard.” When the laughter died down, she had them eating out of her hand.’21 The observation about wristwatches would have pleased the crowd. Wristwatches were a status symbol and still relatively expensive.

Miners, farm workers, mill hands, plantation labourers and people of small towns would have felt familiar to Devanny. From her affection and commitment to Queensland, she would write four novels set there: Sugar Heaven (1936), Paradise Flow (1938), Roll Back the Night (1945) and Cindie (1949), and two non-fiction works, By Tropic Sea and Jungle (1948) and Travels in North Queensland (1951).

The inspiration for Sugar Heaven came during this first trip. At the time of her visit there was a push from the cane cutters to improve their pay and long hours. Added complexities, which Jean wove into the story, came about from the influx of non-unionised Italians working in the area and the incidence of Weil’s disease, a very unpleasant and painful skin condition that afflicted the cane cutters. Interestingly, Drusilla Modjeska names it as her favourite of Devanny’s work. Other commentators have harshly criticised it, and Devanny herself saw that her desire to proselytise and preach on workers’ rights and conditions had overwhelmed the narrative.

The edition I borrow from the Auckland Library is a beautiful modern antique, published in 1936 by Modern Publishers, 191 Hay Street, Sydney. Long ago it was lovingly covered by a librarian in the same thick pale-green and white flecked wallpaper I remember from childhood visits to the houses of elderly relatives. Two lending record slips have come loose in the front. They are headed TIME ALLOWED FOR READING, followed by a stern warning that the time must not be exceeded or the reader will be charged THREE PENCE FOR THE FIRST WEEK OF PART THEREOF and ONE PENNY PER DAY thereafter. The novel is over 300 pages long. How many readers had to part with their pennies, or were forced to return it before they’d finished? The first borrowing was on 5 May 1937, and the book was issued fairly frequently after that until 1948, when it fell very much out of favour, or perhaps for a period it was lost. The next time a reader wanted it was October 1967. Somebody else may have tried to borrow it in 1976 but the date has been scratched out. To hold this book in my hands is to be transported back to the war years.

On the inside cover, which has at some point come adrift and been glued to the frontispiece, Jean Devanny is described as ‘a well known Australian publicist and author’. In 1935 the word publicist retained some of its old meaning. Over the course of a century it had gone from describing a writer on the law of nations to what the Shorter Oxford Dictionary calls ‘a writer on current public topics’. It was only five years earlier, in 1930, that ‘publicist’ had entered the dictionary in its current meaning of ‘publicity agent’. It is probable that Devanny and her publishers leaned further towards the older meaning of the word. The use of the word here, then, is to announce to the reader that this is a valid contemporary novel by a writer who knows what she’s talking about.

Sugar Heaven is in some ways a Queensland version of Dawn Beloved, set a decade or so later, in 1935. It too is about a young woman coming to terms with the restrictions and true nature of marriage. Dulcie, like Dawn, is learning about life from a more worldly husband. Dawn’s husband Val was a miner; Dulcie’s husband Hefty is a cane cutter. Just as Dawn was, the young wife in Sugar Heaven is occasionally overwhelmed by conflicting urges: ‘Her cheeks flamed now, with shame. Hate and desire had intermingled in the ancient inscrutable way and Dulcie was totally unprepared for such a manifestation.’22

The couple are newly married. Each of them has a secret past. Hefty has been married to livewire Eileen, who is now married to his brother Bill and conducting a clandestine affair with one of the Italian workers. Dulcie’s secret is that she was a scab during an industrial dispute in Sydney. When Hefty finds out about this, he sees it as evening things up between them, since he had neglected to tell her about the existence of his first wife. Husband and wife barely know one another, and Dulcie does all she can to avoid sex with Hefty, just as Dawn did for a time with Val, until both wives discover they enjoy it.

In this novel Jean Devanny concerns herself not only with sex, marriage, workers’ rights and conditions, but also with the Aboriginal predicament, a tragedy that would distress her throughout her years in West Island. Hefty’s brother Bill tells Dulcie about the hunting parties:

‘I’m sorry if I’ve hurt you, Dulcie, but you must face facts. It is true that our early settlers used to hunt the abos as they now hunt kangaroos and wallabies. It was particularly abominable up on the Tablelands. They used to drive the blacks into trees, fire the trees and shoot them as they dropped from the branches to avoid the fire. They drove them into rivers and picked them off that way. They poisoned their food. They commonly left abo babies to die after killing off their parents. They used to boast about their day’s bag of blacks as they now boast about their bag of birds or kangaroos …’23

Bill’s lesson arises out of a discussion about the treatment of Kanakas on the cane fields after the introduction of the White Australia Policy. Kanakas, hailing from Melanesia – and in many cases blackbirded – were also starved, their wells and food supplies poisoned, since it was cheaper and easier for some of their employers to do this than to pay for their workers’ repatriation.

Closer to Devanny’s personal experience is the Communist Party’s treatment of Eileen, who decides she would like to join the organisation after the sugar-cane workers’ strike. She is refused membership because of her affair with the Italian. Her husband tells her, ‘You’re a fool to think you can play around like this and at the same time attain membership of the Party.’24 When she and Dulcie eventually become friends, Eileen confides, ‘Then the strike came. It made me want to join the Party. But they won’t have me. Party women have to be conventionally pure it seems.’25 This is nothing less than a cry from the author’s own heart.

When the men go back to work not much progress has been made, and there is infighting within the Australian Workers’ Union and other labour organisations. Throughout the novel Devanny is critical of the monolith sugar corporations but goes easy on the small farmers, explaining that they are just as much at the mercy of the big companies as anyone. This sympathy, along with her criticisms of the CPA’s attitude towards women, did not endear her to party officials.

Towards the end of Sugar Heaven, Devanny tries to weave together Dulcie’s personal life and the political environment. The result is clumsy, almost risible:

The strike situation had thrown up out of obscurity more issues than the bare one of class. She was led to think, deeply and almost with fear, of the need of a man for a woman. Her old conception of sex repelled her now. She glimpsed sex as a real force, apart from love; as a physical necessitous urge like food hunger, satisfaction of which meant clearer action for the class, clear heads, quiet bodies, better men. With inward love tremors she visioned Hefty’s eyes at certain times when he had emerged from her embrace. How clean and pure they had been! And once, when he had been terribly worried about the strike, and she had loved him in her dainty, yielding and yet withholding way, he had murmured: ‘How you have helped me! Good comrade!’26

Dale Spender, however, is apposite on this typically Devanny-ish, uncomfortable shackling together of sex and politics. She writes, ‘I am critical of The Butcher Shop, for example, which in its brave and bold assertion of women’s right to sexuality, seems to give sex and satisfaction too much significance as a solution. But some of her political novels … such as Sugar Heaven and Cindie … were for me a salutary introduction to the political/social/racial – and misogynist – history of Australia. I would recommend Jean Devanny’s fiction to all alert, intellectually active individuals who cherish the dream of a just world.’27

Of Sugar Heaven’s genesis Devanny herself wrote: ‘I collected up all the facts of the struggle and organised them into a book, fact in the form of fiction … This book went far beyond the new vogue in writing at that time: the creative reporting (reportage, it was called), invented by Austrian/Czech Egon Kisch and popularised by him throughout the literary world.’28 Egon Kisch was a communist literary celebrity whom Devanny was to meet when she returned to Sydney. He had been refused entry to Australia, being forced to sit a language test in Gaelic as a ham-fisted means of keeping him out of the country. Language tests were a weapon of the White Australia Policy, and usually conducted in English. Perhaps, when the authorities really wanted to keep someone out, they hit them with Gaelic. Kisch could speak several languages but Gaelic wasn’t one of them. Undeterred, he jumped ship in Melbourne, breaking his leg in the process. The injury did not prevent him from speaking to rallies of thousands in Victoria and New South Wales. He also influenced the writing of social realism in Australia, including Devanny’s novels.

It could be that Devanny’s friendship with Kisch, by whom she seems to have been entirely captivated, went a little way to assuaging the next tragedy in her life. It was heartbreak of the kind that only the strong survive, and one she had already endured: the death of a child. There is no record of who made the decision to keep her in the dark about it until she returned to Sydney, but that is what happened. She was told on arrival that her son Karl had passed away.

Biographer Carole Ferrier maintains that Karl had Tb, not a heart and thyroid problem, which is what the Devannys believed. He was often bedridden, with the added complication of what doctors thought was a type of rheumatism. At the time of his death he was only 22 years old.

‘For the second time in my life the sun went out,’ wrote Devanny.29 She was plunged into a deep depression, part of which was caused by guilt. Would Karl have died if she had stayed at his bedside to nurse and care for him, to make sure he ate well and to keep his spirits up? She had left a very sick young man to fend for himself. Not only had she killed the angel in the house, but she’d possibly hastened the death of her own son.

Point of Departure contains very little about Karl’s death, an omission that Miles Franklin questioned. In the late 40s and early 50s Franklin read and re-read the manuscript, and carried out a lengthy correspondence with Devanny throughout the writing of many drafts. In one of Devanny’s letters, obviously in relation to Franklin’s inquiry about Karl’s passing, Devanny replied, ‘My son, Miles. I can’t write about his death …’30

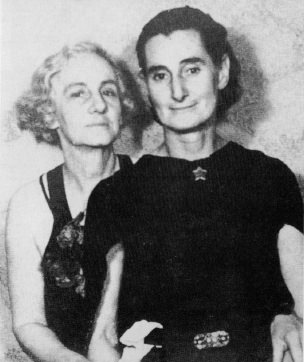

Jean Devanny with Katharine Susannah Prichard sometime in the 1930s. The two women had much in common – their careers as writers and their communism – but their friendship was tested and wavered.

In her grief, she threw herself into her work. Early in 1935, she and Katharine Susannah Prichard set up the Writers’ League with help from Egon Kisch. This is perhaps Devanny’s most lasting legacy, since by a fairly convoluted process the league combined with a later organisation, the Writers’ Association (of which Devanny was president), which would eventually become the Fellowship of Australian Writers, and then the Australian Society of Authors.

Devanny and her husband saw little of each other through this period – it is Kisch she writes about the most. When he left Australia she was bereft. Perhaps they had become lovers, or perhaps it was just – although ‘just’ in these circumstances is rarely descriptive – an affair of the mind.

In April 1935 Devanny went back to Queensland for eight months. She spoke openly about the possible war looming on the horizon. The Communist Party’s official line was that the USSR was at risk of invasion given the rise of fascism in Europe, the Japanese invasion of Manchuria and the continuing Depression. In Queensland there were large, peaceful public meetings, with none of the riots that often erupted at meetings of similar size in Sydney. It was during this eight months away that Devanny formed a sustaining friendship with two members of the party in Brisbane, Isaiah (Ike) and Anne Askew. She also caught the attention of Joe McCarthy, who was the organiser for the Cairns party branch. He was attracted to her, but she maintained that attraction was not reciprocal: ‘Joe was devoid of imagination – and having said that, one has said everything.’31 Of all the men in the CPA, including J.P. Miles, McCarthy was one of the most damaging to Devanny. He fell in love with her but in the way an unimaginative man will fall in love: the woman must be his, or she is nothing. When Devanny later needed his support he actively sabotaged her reputation.

Health and money were serious concerns for Devanny throughout the late 1930s. Despite two physical breakdowns she found the funds to contribute to the publication of Sugar Heaven and to write another novel, Paradise Flow. When the latter was published in 1938, Devanny was once again in Cairns, apparently conducting an affair with Charlie Sailor, a married Torres Strait Islander. In North Queensland and in Sydney, her preoccupation with sexual matters was often given vent on the podium. Not only did she express herself frankly on the matter, she was far ahead of her time. The party men, judgemental and sexually conservative, were horrified. Devanny was in some respects their poster girl. She was a famous writer and a popular speaker off the political circuit as well as on it. In January 1939, for example, she was one of the speakers at a dinner held for H.G. Wells, attended by many prominent Sydney-siders. But for all her fame, these party men wanted to control her.

At the end of that year, once again exhausted and wrung out, Devanny came to the end of a longer stay in Sydney. She had been living in a rented room in the Cross, so tiny that she had to keep her suitcases elsewhere. They were stolen, which was a terrible blow, since she possessed so little. She had also suffered two bouts of serious illness. During the first she was given refuge by Miles Franklin at her house in Carlton; during the second she went to stay with a woman doctor friend in Melbourne, who found her a difficult patient. She described Devanny’s ‘unfailing rejoinder: ‘But you see, dear, you don’t understand. That’s not correct thinking.’ And went on: ‘I’m fond of her, but her vanity is colossal. There’s no argument, she’s simply right. Marx knew everything from the dawn of civilisation to the end of time …’32

Devanny’s departure to Queensland in 1939 was a sad farewell. ‘My husband accompanied me to the train,’ she recalled. ‘And as he stood beside the carriage window, a wave of regret for the disunity between us swept over me. I fell to weeping.’33 Worse was to come. Within the next 12 months she would be expelled from the Communist Party, an organisation for which she had made the most enormous sacrifices.

By September of 1940, Devanny was living near Emuford, a small mining town near Cairns. She was the only female member of the camp, occupying a tin shelter built for her by fellow members of the party who were working the mine. It was here that she wrote By Tropic Sea and Jungle, the first of her natural history books on Queensland.

Reading it now, it is obvious it is written for a market. The book consists of sketches written in a bright, chatty and intimate manner. Many of them finish very abruptly, as if they were intended for magazine publication rather than to be gathered together in a volume. The book is divided into two parts, the first consisting of short pieces on fishermen and lugger boys, flora and fauna, and life in the sugar towns. Her descriptions of the natural world are vivid, almost photographic. Of a visit to Babinda, she writes: ‘Tree-ferns leaned from the banks; white water rippled over golden stones; great round boulders, banded with fawn, mauve and purple, were mirrored in flat waters against the background of jungle scrub.’34 She describes a python digesting freshly killed wallaby with ‘a hump as high as a chairback’.35 She also listens to men talking about damper, good and bad. One of them says: ‘My experiences with cooks are too numerous to mention. If the cook’s bad it’s summed up in camp by the question, “Who called the cook a bastard?” and the reply “Who called the bastard a cook?” There are cooks and cuckoos. The cuckoo’s the bastard.’36

She relates a story told her by an old man about the half a dozen tribes of Aborigines who once inhabited the area:

It was the influx of Chinese that wiped them out. The Chinese grew bananas on the Tully River and employed Abos almost entirely. They paid them a small wage, and got it back by selling opium to them after they themselves had smoked it. This, together with venereal disease and influenza, wiped them out by the hundred. The poor devils would soak the opium charcoal in hot water and drink it. In the ’nineties I’ve gone into camps and found the whole bunch – men, women and children – dead to the world. Couldn’t kick a grunt out of them.37

Devanny has the ear of an oral historian. We can almost hear the old man’s voice telling this shocking, tragic tale, clear down the years, as if it was recorded.

The second section of the book finds the author camped at Emuford. It seems the men with whom she shares her camp are kind and generous. At one point she is given a native cat, or quoll, as a pet. It escapes, but not before she has delighted in its ‘upheld white paw, its defiant but wild gaze’.38 She is fascinated by the insect life, making careful observation of various species of ants and a terrifying sounding creature called a fish-killer, a three- to four-inch insect that kills small fish and frogs with its strong forelegs, and can both swim and fly. At one point she refers to herself as a ‘collector’, since she is sending much of what she finds down to Cairns.39 In the early 40s there was still much to be discovered and understood, and amateur collectors such as Devanny would often do as much damage as good. She describes killing snakes, and accompanying loggers to take out the last of the red cedar. On another occasion she shoots a rat-kangaroo, having described how the marsupial gives out simultaneous sounds of a ‘blurt and thud … what is described in vulgar terms as a “raspberry” every time his hind legs hit the ground’.40 She is, of course, mistaken. An animal would require a peculiar anatomy to allow it to fart on every leap.

So taken is she with the gassy kangaroo-rat that she tries to trap one. When this is unsuccessful, she and her companions shoot him: ‘We found that the bullet had blown off the lower jaw and gone through the bottom of the heart. He was a buck, well grown, as big as a large hare. His thick fur was very soft and white near the skin, red-tipped on the back and less so on the sides. His hard tail was practically the same length as his body.’41

As the ravages of pollution, climate change and overpopulation wipe out much of what wildlife we have left, it will become increasingly difficult for us to imagine how this jolly account could be given by a woman of intelligence and compassion. People who kill endangered animals in our world are pilloried, loathed, and suffer the ignominy of their triumphal photographs going viral. In the 1940s the ancient paradigm of man at the mercy of nature prevailed: there were far more of them than there were of us, and we had every right to kill whatever animal we liked. The supply was seemingly inexhaustible.

The authorial presence in By Tropic Sea and Jungle is bubbly, curious and optimistic, and gives no hint of the horrifying event that would happen at Emuford. The communists who had invited Devanny to join them, all men, grew tired of her lecturing. As it was, they were all under some degree of police surveillance thanks to Devanny’s reputation as a rabble-rouser. Then a local woman spread a rumour that she had seen Devanny having sex in the open air with one of the men, Murdoch Macdonald. When the rumour reached Devanny she was furious and asked Macdonald to do something about it. Instead he struck her, and refused to talk to the local woman and others who were convinced of the story’s veracity.

Many women, in this situation, would keep their own counsel and take some sort of cold comfort from the knowledge that the rumour was lies. They might wait for the story to die down and for the truth to out. More sensibly, they might disappear from the area, never to return. Not Devanny. She made the journey northeast to Cairns and asked Joe McCarthy for help. He gave her his assurance that he would help her, but then made himself scarce. When she couldn’t find him, Devanny returned to Emuford alone. This was a serious mistake.

It is certain that the men in the camp assaulted her, and probable that she was also raped by more than one of them. Sometime afterwards she was taken to hospital by ambulance and the men, in time-proven fashion, let it be known that Devanny had been willing, and that she had been working for them as a cook and general dogsbody. And so insult was added to injury: not only did they assault her, but they demeaned and devalued the work she had been doing there.

Charges were not laid against these men, and Devanny herself kept quiet. She repaired to her old friends, the Askews, with whom she was still staying when Ike Askew died in early March. Around this time she had the operation mentioned in her letter to Miles Franklin. It was a radical hysterectomy. The only person who ever knew the truth of what happened at Emuford, aside from Devanny and her assailants, was Anne Askew. A loyal and true friend, she kept Devanny’s experience to herself and the secret died with her.

Inevitably, stories of Devanny’s supposed sexual activities at the mining camp reached Sydney. They resulted in her expulsion from the party. Some of these stories were trite: she had, for example, been seen swimming in the nude. Some of it was pure, vindictive gossip: a trade union official’s wife told her she was a homewrecker. Her moral conduct, so called, was the major reason for her expulsion, the news of which came to her while she was convalescing in Brisbane. Men will believe other men, something that Devanny knew only too well. She did not protest her innocence, although there is evidence she did write a statement about the event and its aftermath and sent it to J.B. Miles in Sydney, where it was destroyed.

Much of Devanny’s conduct during the following year was so deranged and destructive that a modern psychologist would likely diagnose her as suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. There were attempted reunions with Hal in Sydney, even though he apparently beat her when he learned of her expulsion from the CPA. She demanded that he ditch his girlfriend and support her, despite the fact that he had had a mild stroke. Hal, whom she always criticised for his mild manners and lack of spunk, agreed to her demands, and for some time they battled on together in a house in Neutral Bay. There were also ongoing skirmishes with various members of the Communist Party who were, it is easy to see with hindsight, terrified of what Devanny could publicly say about her treatment at their hands. J.B. Miles, devoid of any residual affection from their long-running affair, had no sympathy for her, as was demonstrated in 1942 when Devanny made a special trip to Sydney on his instigation. Perhaps she hoped he would apologise, or go some way to recompense her for her injuries. Instead, he warned her not to write or say anything negative about the party. Even Katharine Susannah Prichard failed to stand by her. In Pat Hurd’s addendum to her mother’s autobiography, she writes that despite Prichard’s supposed friendship, when Devanny was ‘hard-pressed and suffering, KSP does nothing to help; she lines herself up with the prosecution!’42

In the early 1950s, while Miles Franklin was assisting Devanny in her efforts to find a publisher for Point of Departure, the manuscript was given to an anonymous journalist to read. The journalist was a man with connections to the Australian Labor Party. His response, which Franklin sent to Devanny, must have gone a little way to assuage these old hurts:

The hatred of the intelligent – the writer – and intellectual is a hangover from the old Labor party … If we weren’t so hopeless in the Labor Party there would be a proud place in it for the Jean Devannys of this world. Instead, we let them go over to the Commos who turn them into working cattle. Read the itinerary handed out to Jean year after year. It would kill an ox. What courage – integrity and fundamental decency. She threw her husband, her children, herself and finally her health into this Cause – only to be finally and contemptuously rejected.43

Although the expulsion from the Communist Party was difficult to bear, in the long run it did Devanny a lot of good. She healed slowly, and she returned to Queensland where she spent time on Magnetic Island and on the Barrier Reef. By Tropic Sea and Jungle was published in 1944, and Cindie, her last and, to my mind, best novel, in 1949. Separated once again from Hal, she conducted an affair with an older man whose identity she guards throughout her memoir, but he may well have been Dr Hugh Flecker, a natural scientist who had been encouraging of her efforts in that direction. A whole chapter of Travels in North Queensland is devoted to a trip she makes with him to Low Island Reef to collect coral and shells and discover species of mollusc, starfish, algae and rare coastal plants. He had no affiliation whatsoever with the CPA, and was indeed antipathetic to it. At one stage he asked her to marry him, but only if she had relinquished all connections. She had not, and would not, until 1950, by which stage she was living peacefully enough with Hal in a rented house in Townsville.

Devanny, perhaps, had contracted some version of Stockholm syndrome to go alongside the possible PTS: she wanted, throughout much of the 40s, to be reinstated as a member of the party that had treated her so badly. When they did finally re-admit her it was only a brief contretemps. At the point she was able finally to turn her back on the party, she labelled them all ‘liars, cheats and miscreants’ – an opinion that held until five years before her death, when she mysteriously re-joined.44 It was the party’s response to her historical novel Cindie, rather than the scandalous lies they had disseminated about her personal conduct, that forced her resignation. The Communist Party newspaper, Tribune, refused to review it. The official line was that Devanny’s portrayal of the mistreatment of Kanaka labour in the Queensland sugar fields at the turn of the century was incorrect. It was not: Devanny had done her research and believed that the ‘the cruelty [to the Kanakas] lay chiefly in the recruiting’ – that is, blackbirding. Further, she held that their conditions on the plantations were the same as those handed out to white men after the White Australia Policy came into play and Kanaka labour was ended.

‘There was a picture in their minds, I fancy, of the “noble savage”, a picture as far removed from reality as anything well could be,’ wrote Devanny.

Impossible for them to envisage the conditions in most of the islands from which the Kanakas were recruited or ‘blackbirded’: the hunger, the filth, the cannibalism, the fear of primitive magic, the deadly internecine feuds incessantly raging between the tribes – and the comparison presented by their Queensland mode of life … Not that I am attempting here to excuse the cruelties and abominations of blackbirding. Or to minimise them one jot. Why should I? My whole life-work and outlook, my ingrained acceptance as a New Zealander of the coloured man as equal with white, my studies in anthropology, my cultivation of coloured persons as personal friends, my writings – all together, these establish that a tolerant attitude towards injustice perpetrated upon coloured peoples is not to be numbered among my many faults … many Kanakas were opposed to enforced repatriation.45

J.B. Miles, whose opinion she still valued, refused not only to read the novel but to discuss it with her. Perhaps he knew that he would be on the receiving end of such high-handed statements as the one above – a typically New Zealand response to accusations of racism. As far as Prichard’s desertion of Devanny goes, it probably had more to do with this issue surrounding the portrayal of the Kanakas rather than those surrounding her friend’s apparently scandalous behaviour.

Many of us, having had doses of Christianity in our childhoods, will return to the church in our senior years. Devanny’s devotion to the party was so devout that the loss of it in late midlife left a great gaping hole in her heart and mind not easily filled by anything else. Perhaps the motivation to rejoin was more spiritual and emotional than intellectual, particularly as the party was at that time trying to persuade her not to publish her autobiography. Her long letters to Miles Franklin regarding the manuscript demonstrate that she herself had grave doubts about the book, not so much from anxiety about who or what she might expose but about its structure and pace, its value as literature. When the book was rejected by a publisher in 1953, Devanny had one sad sleepless night, but wrote to Franklin the next day: ‘this morning my irrepressible optimism is once more flying the flag’.46 Publication of the memoir during her lifetime would doubtless have resulted in much argument and accusation. It was not until 1986, long after her death, that it finally broke into the world.

In the same letter to Miles Franklin, Devanny expressed her sorrow at a letter from a ‘loved sister in New Zealand’ who told her about the family’s pride in her early career as a writer, but also ‘how disappointed and shocked they were when I gave it all up for “notorious” politics’.47 Part of her distress, perhaps, was her sister’s ignorance of the work that had come later, despite the ‘notorious’ politics. The sister must have missed the reviews. In a 1950 letter to Franklin, Devanny mentions some critical response to Cindie: ‘I have had some good reviews of my last book from NZ, where it seems to have caused a stir in the literary world, which pleased me greatly. One critic suggested that I should return home and devote myself to my own country.’48

The intimate correspondence between these two very different but important writers was sustaining to both of them in their later years. It is shocking that Miles Franklin, a scion of Australian letters, was at the end of her life often lonely and in relative penury. In 1954 Devanny wrote to her: ‘I can’t bear to think of you desolate, as you state, sitting alone in that house from which you can’t look out … The only thing I dread in life is loneliness. While working hard I did not know the meaning of the word, but now I absolutely refuse to have Hal leave me alone. He knows. He had his day – the twenty years in Sydney while I was on the loose, scrounging a crust for him, and now he will meet my needs. I am finished with being a doormat for any worthless creature.’49

Such bitterness! No wonder Hal told a visitor that he thought Devanny was frequently quite unhinged, and that he often did his best to avoid her. Fourteen years earlier Devanny had written to Prichard: ‘Hal is tremendously useful to me politically, but otherwise I have to count him out. He has been trying to get to NZ for a long time, but he would have to be born again to achieve any dynamic at all … He is no good to me, as a husband, as a provider, or anything else, yet he stands between me and any sort of happiness at all, since the eyes of the workers are on me. The P[arty] provides me with a pittance, otherwise I would starve.’50 We often lash out at the people closest to us, and Devanny, plagued by frequent ill-health, rattling with self-doubt while giving every appearance of being convinced of her own correct thinking – a zealot in many ways – lashed out more than most.

Devanny’s daughter Pat, who also had periods of estrangement from her mother, believed that her mother’s last years in Townsville were predominantly happy ones. She had a couple of close friends, a productive and beautiful garden, and a great curiosity and love for the animals and insects that shared it, including a pet python. She went swimming in a tidal creek near her home without fear of crocodiles or sharks, rode her bicycle everywhere, and watched two movies a week at the local cinemas. Aside from her correspondence with Miles Franklin, she also exchanged letters with many others, including natural scientists and aspiring writers to whom she was always encouraging.

And, despite everything, she had Hal, who would outlive her by two years. After almost two decades of hard slog in New Zealand, together they had crossed the Tasman in search of a new and better life, by which stage they were in their thirties. The life they had in West Island was certainly new, and different in ways they could never have imagined. Had Devanny joined the Communist Party in New Zealand and fallen in love with the leader; if she had informally dissolved her marriage and conducted affairs with other men; if she had gone on to write more novels set in the land of her birth that questioned that status quo and said hard things about her own colonial history – what then? It is possible she would have ended up a pariah, more isolated than she ever felt in her little house in Townsville. Devanny had a big, abrasive personality, more suited perhaps to stereotypical notions of the Australian national character than the supposedly more sombre, private, quiet Pākehā.

The departure from the homeland often affords the traveller or emigrant an opportunity to re-invent themselves, to become someone else. Devanny’s friend Kay Brown apparently stated that ‘Devanny found New Zealand social conditions had not offered sufficiently fertile ground for the socialist project to which she was committed.’51 That may or may not have been true, had it been put to the test. What can be stated with some degree of certainty, is that Devanny would not have become the woman she was if she had stayed at home in a smaller country, with all the strictures and restraints placed on her by the demands and expectations of relatives and long-term friends.

Perhaps the penultimate word on Devanny’s longstanding reputation in New Zealand could be from John A. Lee, who wrote in his 1977 letter to Andrée Lévesque Olssen, ‘Jean Devanny, strange how completely she vanished. There is no grave as deep as the Commo party.’52 But she didn’t so much vanish into the party as disappear behind the iron curtain that hangs across the watery border between our two nations. It seems that the curtain may have opened a chink to allow Devanny’s work to slowly regain ground in the years since her death, ground that could metaphorically be thought of as a small island. This fictional island, the one we imagine her happily inhabiting, is not a tropical cay of the kind she was so fond of and wrote of so winningly in Travels in North Queensland. Instead it lies fittingly in the middle of the turbulent, stormy Tasman Sea, and so allows both sides of the ditch to lay claim to this extraordinary, brilliant, highly sexed, maddening, ferocious, inexhaustible woman called Jean Devanny.

Of my five West Islanders she is the one I would most like to have met.