By 1972 most of our West Islanders have passed away: Jean Devanny in 1962, Eric Baume in 1967 and Roland Wakelin in 1971.

This is the year the parties end for Dulcie Deamer – though, who knows, perhaps she’s still conducting kissing competitions and doing the splits in her leopardskin suit in whatever wild wine-soaked heaven bohemians go to when they die.

Nationally, there are many changes. Some are far reaching and begin to define the Australia we know today. On 26 January the famous Aboriginal Tent Embassy is set up in Canberra. Among its co-founders are activists who will become household names, among them Gary Foley, Roberta Sykes and Mum Shirl. This year pastor, activist, sportsman and governor Douglas Nicholls will make history as the first Aboriginal to be knighted.

At the end of the year Prime Minister William McMahon will be replaced by Gough Whitlam. It is the first Labor government after 23 years of a Liberal Country Party coalition regime. Their slogan ‘It’s Time’ is mirrored on the other side of the Tasman when the New Zealand Labour Party comes to power under Norman Kirk, ending a 12-year reign by the National Party.

Two Australian women triumph on two wildly divergent international competitive platforms. In the sporting world swimmer Shane Gould excels at the Munich Olympics, winning three gold medals, one silver and a bronze. In recognition of her achievement she is made Australian of the Year. In Puerto Rico Kerry Anne Wells is crowned as the first Australian Miss Universe. As the decade wears on, feminist opposition to beauty pageants will become more strident.

After decades of smoking as a social norm, ‘Smoking is a health hazard’ is introduced as a warning in advertising for cigarettes and tobacco products. Next year, 1973, the warning will be printed on the packets themselves. Australians continue to puff away as if there’s no tomorrow.

In the world of books, Thea Astley wins the Miles Franklin Award with her novel The Acolyte. It is the third time since 1962 she has won the prize, which is an extraordinary achievement in a literary environment dominated by men. Thomas Keneally’s novel The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith is nominated for the Booker Prize. The story is based on the life of Aboriginal bushranger Jimmy Governor and told from his perspective. In his later life Keneally will say he would not now attempt that point of view. In six years a film based on the novel will be made.

The theatre world is thriving. Playwright Alex Buzo wins the Australian Literary Society Medal for Macquarie: A play, and also for Tom. David Williamson’s iconographic play Don’s Party is produced in Sydney for the first time, to mixed reviews.

Commercial radio is dominated by the band Led Zeppelin (which is this year touring Australia and New Zealand), along with Cat Stevens, Jethro Tull, Don McLean, Neil Young, Slade, Deep Purple, John Lennon, Elton John, Rod Stewart, The Rolling Stones, America, Paul Simon, Wings. Australian Helen Reddy will record her anthem of the moment, ‘I Am Woman’.

The Adventures of Barry McKenzie, which could be seen as a kind of precursor to the more famous Crocodile Dundee (1986), is the film of the year. It’s a story of an Australian yobbo on his travels to the UK. Among the cast is Barry Humphries, who has several roles including that of Aunt Edna Everage from Moonee Ponds. This character will later become world famous as Dame Edna.

And although we may think the terrorist threat is recent, Sydney suffers on 16 September a bombing in Haymarket by Croatian separatists. The target is the Yugoslav General Trade and Tourist Agency and 16 people are injured.

What, then, of our only surviving West Islander? Douglas Stewart is 59 years old and living in the suburb of St Ives, Sydney. Three years ago his friend and colleague Nancy Keesing published her lengthy essay, ‘Douglas Stewart’, as part of the series Australian Writers & Their Work. He is one of the most famous Australian writers of his era, having written across genres – plays, poetry, short stories and criticism – for nearly 30 years. He is also a long-term gatekeeper for Australian letters, having been for 14 years the literary editor of the Bulletin, then editor for publishers Angus & Robertson.

On Boxing Day 1972, biographer Doctor Clement Semmler arrives with his reel-to-reel tape machine to interview Stewart about his life and work.

The week I begin this chapter both Australia and New Zealand are in mourning for much-loved comedian and satirist John Clarke, who has died suddenly in Victoria at the age of 68. Such an outpouring of grief for a trans-Tasman identity, missed equally on either side of the ocean, is a rare and precious thing. In the New Zealand Herald a satirist who stayed home pays tribute, recalling an interview he did with Clarke in 1997. ‘He loved poetry and all its magic tricks; some of his best and most closely observed satires were of poets whose work he loved,’ writes Steve Braunias. ‘He thought of New Zealand as a kind of distant aunt. There simply wasn’t the work and there was also the obstacle of New Zealand television programmers and executives, many of whom he regarded affectionately as vermin.’1

Douglas Stewart died in 1985. The deaths of these two famous New Zealanders who made their homes in Australia are separated by some 30 years, but there are some similarities. Stewart was a writer and editor, not a comedian. Even so, he may well have espoused his dear friend Norman Lindsay’s theory that all artists are entertainers. He may not have thought that the authorities in the New Zealand literary scene (his equivalent to Clarke’s chosen medium of television) were vermin, but he did feel unjustly abandoned by them. He said as much to Vincent O’Sullivan, who visited him in Sydney in 1984 and recalled that he ‘liked him very much’.2 For the young O’Sullivan, visiting Stewart was a kind of pilgrimage: ‘Stewart’s “Ned Kelly” was one of the first professional plays I saw – a brilliant production with the Campions’ NZ Players, and I definitely owe my later interest in Australian writing to the start that play gave me … I think Douglas was touched that a younger NZ writer made the effort to call on him, as I very much felt that he thought our literary “establishment”, by which he meant mainly Curnow and Glover, had condescended to him, and resented his opting to live in Australia, and become so successfully part of its literary world.’3

This sentiment expresses the peculiar phenomenon we have already witnessed with Devanny. If a New Zealand writer goes to Australia and fails, he/she is forgotten. If a New Zealand writer goes to Australia and succeeds, he/she is even more forgotten. The amnesia becomes aggressively conscious. Writer and activist Rosie Scott (1948–2017), a more recent and very successful West Island import, had the same experience, even though the novel published four years before she left, Glory Days (1984), was clasped to the collective bosom and became an international bestseller.

Among Stewart’s papers in the Mitchell Library is a 1980 letter from another New Zealander, academic and writer Peter Simpson, who was then researching for his 1982 book on New Zealand novelist Ronald Hugh Morrieson. Morrieson’s The Scarecrow and Came a Hot Friday had been published during Douglas Stewart’s time at Angus & Robertson.

‘I have often wondered how it came about that Morrieson was first published in Australia instead of in New Zealand,’ writes Simpson:

Did he attempt to place his novels with NZ publishers first and only turn to Australia after his MSS were rejected here? Or did he immediately send his MSS to Australia? Perhaps you might be able to throw some light on these questions for me? It has always seemed to me that there was a certain rightness in RHM’s first being published in Australia and meeting there greater acceptance than he has still (except for a growing minority) found at home. An easy relationship with his native environment is perhaps more typical of Australian writers than New Zealanders and Morrieson brought into New Zealand writing certain qualities which had been present in Australian writing for decades. Some Australian reviewers of the novels ... have seen affinities between Morrieson’s books and Norman Lindsay’s Saturdee and Redheap … Do you think RHM might have been directly influenced by Lindsay or other Australian writers?’4

There are other questions in the letter. Simpson is especially curious as to why Stewart had rejected Morrieson’s third and last novel, Predicament, then called Is X Real? Stewart’s answer is simply that he hadn’t liked it as much as the others. He explains that two years after the rejection, Morrieson sent ‘a strange explosive letter’ expressing the usual writers’ anguish about poor sales and laying blame at the publisher’s door.5 Stewart invited him to submit another novel but Morrieson, by then in the throes of advanced alcoholism, only re-submitted the first one with a new title and a few minor changes. It could be that Morrieson felt he had an ally at Angus & Robertson in the shape of a fellow Taranakian, and the rejection of Predicament felt like a betrayal. In an email to me, Peter Simpson wrote, ‘It’s still surprising to me that they wouldn’t publish Predicament which is not notably inferior to the first two in my opinion. I wonder if it would have made any difference to Ron’s downward slide if they had?’6 As any writer knows, rejections are especially painful. Simpson’s suspicion that Morrieson would have been buoyed by an acceptance is very likely correct.

In a curious postscript to Stewart’s and Morrieson’s troubled association, a film was made in 2010 of the rejected novel. Despite starring the brilliant Jemaine Clement, it is a rather bad film and garnered poor reviews. For the Dominion Post, Graeme Tuckett wrote: ‘“Predicament” is adrift … Poor casting and some underwhelming performances kill it stone dead.’7 Rather eerily, the film was partially shot in Stewart’s hometown of Eltham.

Neither Simpson nor O’Sullivan made contact with Stewart with the particular aim of talking about Stewart’s own writing, although O’Sullivan could have told the grand old man of letters, as Stewart was by then, how much he had enjoyed the ‘rich and vivid’ language of Ned Kelly.8 The year before O’Sullivan’s visit, in 1983, Stewart received a letter from a fellow grand old man of letters who had stayed in Aotearoa but had briefly escaped to West Island. Historian Keith Sinclair had netted a writing fellowship at Australian National University in Canberra. In the letter he wonders if Stewart remembers him from about 1959, when Sinclair was writing a history of the Bank of New South Wales in New Zealand. Stewart had written a piece about him in the Bulletin and someone had done a drawing of him. The purpose of his letter is to say how much he loved the newly published Springtime in Taranaki: ‘Offhand I can’t think of an NZ autobiography nearly as good. Both Brasch and Sargeson were so evasive about their love life, I mean. Your book reminds me a bit of Laurie Lee’s Cider with Rosie: both books are lyrical … I think your pic looks whimsical, sardonic, a bit uptight. My wife says “cheeky”.’ In a casual postscript he adds, ‘Oh – I shall be in Sydney 17–21 December, if you’re going to be in the city’, and gives Stewart the phone number.9

There is of course a very good reason why Stewart could be brazen about his youthful sexual adventures, and Charles Brasch and Frank Sargeson were not. Both were homosexual, Sargeson more openly than Brasch. To have written frankly about their love lives would have been tantamount to committing professional suicide. It seems odd that Sinclair would make this comparison, because he must have known about Sargeson, if not about Brasch. The literary scene in New Zealand was so small it was difficult to keep private lives altogether private.

During his years in West Island, Stewart received many other visits and letters from New Zealanders, whether resident in Australia or passing through. Two years before he left the Bulletin, Brasch, poet and founding editor of the literary journal Landfall, had called on him at his Bulletin office. Brasch kept journals throughout his writing life and left a vivid record of that 1956 meeting:

He works in a dingy shabby badly lit partitioned-off little room by a window hard against a building & admitting only a grey half-light – he sat with his back to it so that I couldn’t see him well. A spare dark-faced man with smooth dark hair & dark eyebrows, a little smaller than I am, speaking quietly & pleasantly. He was reserved & cautious, I felt, but I tried to be friendly & I think he thawed a little; I liked him almost at once. He had been to Canberra for a meeting of the Board of the Commonwealth Literary Fund. A romantic I suspect.10

Stewart himself recalled his working environment rather more favourably, as a romantic would: ‘The Bulletin was one of those immensely civilised offices, now probably vanished from the earth, where you could do your own work in your own time and completely ignore everything and everybody if you happened to be taken by a ballad.’11

Brasch and Stewart talked about William Hart-Smith, a now almost forgotten poet who had arrived in Australia from New Zealand around the same time as Stewart. Stewart was so much an admirer of Hart-Smith’s Columbus Goes West, published in 1948, that he was able to quote from it: ‘two rather obvious romantic passages’, commented Brasch, airily. They also discussed Denis Glover’s Arawata Bill, which Stewart thought was Glover’s best work. Their conversation turned to Dan Davin’s choices for an important edition of New Zealand stories: Stewart was critical, since Davin had not selected any of the New Zealanders he had published in the Bulletin. They talked about Bill Oliver’s positive review of Stewart’s recent book, edited with Nancy Keesing, Old Bush Songs: Stewart approved. It may well have been through Keesing that Brasch had his introduction, since he and Keesing were cousins. Brasch’s description of Stewart fits with Keesing’s: he was a man whose ‘physical presence would not turn heads’, but who had many deep friendships and a formal, kindly way of conducting himself.12

Stewart obviously liked and respected Brasch. The journal entry concludes: ‘He also invited me to contribute to The Bulletin – verse or stories, rather to my surprise; and asked that LF [Landfall] should be sent regularly for review, & Caxton and Pegasus books. So much friendly interest was unexpected.’13 Brasch may well have found Stewart’s bonhomie and curiosity fresh and unusual. He was likely steeped in the New Zealand literary culture, which very often may be steeped in mutual suspicion and toxic jealousy.

As a further demonstration of the insularity of this period, from Vincent O’Sullivan comes a story related to him by the Australian poet A.D. Hope, who met famous-in-New-Zealand poet Allen Curnow in Auckland. Hope expressed his regret that Australian and New Zealand writers knew so little of one another’s work. Curnow replied, ‘But you don’t realise Alec, we don’t need you.’14

I could fill a page or two here about what lies behind Curnow’s remark: the provincialism, the stultifying isolation, the dominance of the literary scene by three generations of fairly talentless men when, as Australian critic Vance Palmer had remarked mid-century, the best New Zealand novels were being written by women.

Even now there is a sense, when one lives and works in New Zealand, of existing in a parallel universe. Books are published and fade away; they are not often championed by fellow writers, as was my experience as a young writer in Australia. Nothing has any impact unless it wins a prize overseas, no matter how unreadable the book, and nothing much has changed in relation to Curnow’s ‘we don’t need you’. When novelist and university lecturer Paula Morris set up the Academy of New Zealand Letters in 2015 she was subjected to vitriol that arose from the same place. Why would you want to establish relationships between New Zealand writers and those of other countries? We don’t need that. We are fine just as we are, thanks, talking to ourselves. When Peter Wells and I gathered together a group of enthusiasts in 1998 to establish the Auckland Writers’ Festival, we encountered similar opposition from some quarters. At an early festival a leading Wellington literary identity said to me, ‘This doesn’t feel like New Zealand.’ He meant, I think, the collegial atmosphere, the open discussion of ideas and sense of generosity, the fizz of excitement in the air.

What would Douglas Stewart think of how we are now? He certainly never wanted to live in New Zealand again, even though, as we shall see, much of the inspiration for his work throughout his life stemmed from the country of his birth.

On Boxing Day 1972, Stewart receives a very important visitor at his North Shore home at 2 Banool Avenue, St Ives. This is his biographer Dr Clement Semmler, OBE, who arrives armed with a tape-recording machine. Stewart is flattered, I think, that Semmler has chosen him for his subject. He is one of Semmler’s many admirers.

Already the biographer of poets Barcroft Boake (1965), Banjo Paterson (1966) and Kenneth Slessor (1966), Semmler has at this time worked 30 years at the Australian Broadcasting Commission, the last seven of these as deputy manager. Before that he was assistant controller of programming, a role he took very seriously. He is a jazz buff, and thanks to him Australian households in the 1940s heard some of the best jazz in the world. He had inspirational ideas for shows such as The Sturt Report, which he initiated in 1951. It was a popular programme voiced by two actors as they travelled down the Murrumbidgee and Murray rivers, reliving the journey made by Charles Sturt and George McLeary in 1829–30.

In 1969, three years prior to his arrival for this recording session, Semmler was awarded a Doctorate of Letters for his published work, all of it undertaken in his leisure time. One of these, Broadcasting and the Australian Community, was deemed to be so controversial that the ABC commissioner quashed it in 1955. Among other things, Semmler was critical of the legally required presence of two public servants on the commission, believing (as many people did) that it compromised the organisation’s ability to make independent political commentary. The book was accepted by Oxford University Press on the proviso that the commission agreed to it. They did not, and the book was never published. More recently Semmler has been openly critical of the new broadcast medium of television, much of which he regards as frivolous and ill-informed. In five years’ time when Semmler retires, he will fire off furious shots at his employer of 40 years. Not only is the ABC anti-intellectual, he will say, but he doubts ‘if some senior executives had ever read a book’.15 He believes that radio will find its niche as the more serious medium, an opinion that very likely endears him to famed radio dramatist Stewart.

Who is home at St Ives when Semmler arrives? Stewart’s wife, painter Margaret Coen, is certainly there for some of the recording, because she helps her husband remember certain dates and years – for instance, when it was they were married.

‘The fifth of December, 1945,’ Margaret replies when Stewart calls for her help. Does she wonder why her husband can never remember, as married women have wondered for centuries? After all, their twenty-seventh anniversary was only a few weeks ago. Margaret could remember their courtship and marriage clearly, from the first time they met at the end of 1938. Many years later their daughter Meg, adopting her mother’s voice in a loving and sensitive memoir of Coen’s life, will write: ‘I had never met such a dark, intense young man. Doug startled me by suggesting marriage almost as soon as we started going out.’16 She held him off, well aware that married women usually struggle to continue as artists of any kind.

Neither can Stewart remember the year Meg was born, and Margaret supplies that as well. Meg, nearly 25, is in 1972 embarking on a career as a writer and filmmaker. She would have spent Christmas Day with her parents but is not home on the day of the interviews. She is flatting in Paddington and working at the Commonwealth Film Unit, which next year will become Film Australia.

The interviews begin conventionally enough with the subject of Stewart’s childhood. The location of his father’s birth escapes him too, and it seems that his wife can’t help him with that. The Bulletin he describes as his childhood family bible, and he confesses that he had a poem a week rejected by the magazine for years. Eventually, he tells Semmler, a poem was accepted by the Bulletin’s ‘rather disgraceful little sister the Australian Women’s Mirror’, edited by none other than Cecil Mann, who then went on to the Bulletin.17 As we already know, Mann was instrumental in getting Stewart his start as his assistant on the ‘Red Page’.

Why Stewart thinks of the Mirror as ‘disgraceful’ is curious. Dulcie Deamer wrote for it for years, and among the sillier pieces intended simply as entertainment are more thoughtful articles, such as the ones on women in Long Bay prison and women’s refuges, which are well written and well researched. Perhaps his embarrassment about first publishing in the magazine has more to do with the fact it is a women’s paper. It resonates with his response to his first published poem being in the children’s pages of the Taranaki News.

When war broke out at the end of 1939, neither he nor Cecil Mann went to fight. Stewart explains to Semmler, ‘I lasted one day [in the army] and was knocked out on medical grounds and Cecil lasted some weeks before he was bunged out as being too old, he was first world war vintage, and we were swapping jobs around and it became necessary for him to do much more political work and the Red Pages fell to me by accident, more or less.’ It wasn’t as if Stewart was inactive during the war years. As Meg recalls in her mother’s biography, ‘Doug went off to enlist in the AIF [Australian Imperial Force]. I was beside myself. He disappeared into Victoria Barracks for a whole weekend. I cried for two days. But he was rejected on medical grounds, for which I was most thankful … it did seem incongruous that only the fittest specimens were accepted for the slaughter … Doug became an air raid warden.’18

Stewart was rejected from service because of a stomach ulcer. Doctors provided him with a planned diet to help correct the problem. In the memoir of her mother, Meg expresses the opinion that the world was better served by his writing through the war, rather than fighting. They were productive years.

Douglas and Meg Stewart in the Snowy Mountains, Australia, 1960s. Stewart loved fly fishing almost as much as he loved writing poetry and plays. The photograph was probably taken by his wife, painter Margaret Coen.

Meg Stewart collection

Elegy for an Airman, published in 1940, is dedicated to Stewart’s childhood friend Desmond Carter, who was killed in action in 1939. It is Stewart’s third book after Green Lions and The White Cry. The title poem celebrates the boys’ idyllic childhoods, the neighbours and the changing seasons, the games of castles and princes, funerals for dead blackbirds. He writes of how he and his friend mapped the land around for what it offered them – mushrooms and blackberries, or the mud in the Ngaere swamp. In the last three stanzas the youthful poet faces the death of his friend with the statement, ‘No one should die and not be wept by women’.19 The verse ends with the assurance, ‘The women have wept for you, comrade.’ There is the sense of the young Stewart posturing, the poet taking up different stances. Letters from the period imply that he was voting left when his family voted the other way. Hence, perhaps, the use of ‘comrade’, a term in common use among communists as well as soldiers. But the poet’s grief is genuine as he recalls, ‘But I who remember/The childhood as far off as China.’ Towards the end of the poem we are finally with the lost airman as an adult, and Stewart recalls the time they spent together in London before the war: ‘… the way we coughed and laughed in a London fog,/ Remember the way of a man, that you sang and were strong.’

There are 20 other poems in the book, all of them nature poems and fairly slight. Were it not for the one use of the word ‘Maori’ and the reference to the Ngaere swamp, a reader could think Stewart had spent his childhood in England. There are magnolias and pine trees, buttercups and thrushes. Some of the poems may well have been written during his short stay abroad, but it’s likely most of the poems are juvenilia. The English trait was of course common in writing by Pākehā in the 1930s when, for most, New Zealand was little Britain. International readers of many books by Pākehā even now could be forgiven for thinking it is still viewed as such.

Elegy for an Airman shows us Stewart finding his feet two years into his new life in Australia. Illustrated by Norman Lindsay with his trademark naked nymphets looking startled among waterlilies, or naked tree-women with leaves for hair and hands arched over a fallen Icarus, the little book is an artefact of the period. The copy I borrow from the Auckland Library has a sticker affixed to the inside cover: ‘The Churchill Auction 1942’. This was an initiative of Patrick Lawlor’s in Wellington, where ‘literary and art enthusiasts’ were asked for donations from their collections for ‘patriotic auctions in the four centres’. The desired outcome was not only ‘to win the war but to strengthen our National culture’.20

Semmler is keen to discuss Norman Lindsay with Stewart, not just because of Lindsay’s enormous influence on a generation of Australasian artists and writers but also because he was one of Stewart’s closest friends. At the time of the interview, Lindsay has been dead for three years and it’s likely Stewart is still grieving, but in the quiet way we learn later in life, when so many of our friends and relatives have died. It’s also possible that he has had time to think about Lindsay in a more objective fashion.

‘Well I have my doubts about the influence of Norman Lindsay,’ he says, when his name is first mentioned. This would almost have been heresy at this time, but it is not something he says out of bitterness. They were very close, delighting in one another’s company. Stewart, Margaret, Lindsay and his wife Rose spent most weekends together for a period of 14 years.

Lindsay and Stewart had met for the first time in 1938, at Lindsay’s studio in Bridge Street near Circular Quay, then a kind of mecca for local artists. Many painters and sculptors had studios in the area. Stewart had been taken along by his friend and colleague, the poet Kenneth McKenzie, because he had had an idea for a cartoon Lindsay could draw for the Bulletin. It would depict ‘Hitler taking a bath in the Mediterranean and annoying Musso’.21 It was a successful proposition – the cartoon appeared in the Bulletin on 12 May 1938.

Stewart recalls that the first thing Lindsay asked him was what other art he practised. For Lindsay, renowned as a visual artist and a novelist, it was normal to excel at two art forms. ‘I was a raw recruit from New Zealand with only the slightest knowledge of the fine arts picked up during six months in England,’ Stewart wrote later.22 He told him it was sculpture, a total fabrication.

‘I used to be terrified of him,’ Stewart tells Semmler. Lindsay ‘had a very big reputation in New Zealand, but we would have read him only along with Bertrand Russell and D.H. Lawrence and other – Havelock Ellis – other sort of advance guard of the period’.

Stewart may also have been guarded and a little alarmed in Lindsay’s company because it appears that his wife Margaret Coen and Lindsay had been lovers for a period before her marriage, and maintained a great affection for one another once the affair had run its course. Whether Stewart knew about the relationship is unknown. Margaret had a studio not far from Lindsay’s, further along Pitt Street. She went there every day to paint but lived at home with her parents in Randwick. The two spent a lot of time together at Lindsay’s studio, and Margaret would help him by ‘cleaning up after he finished painting and also attended to what I guess you could call “household matters”.’23 Lindsay lived at his studio alone. He was married, but unhappily, and for a number of years he and his wife were informally separated. When the couple reunited for a time and lived together in the Blue Mountains, the Stewarts left their flat in Crick Avenue, Kings Cross, and moved into Lindsay’s studio. They were expecting a baby, and thought it would offer them a little more space. Stewart writes very amusingly of this time in his memoir on Norman Lindsay.

When Semmler presses him on the influence of Lindsay, refusing to accept Stewart’s first pronouncement, Stewart demurs, pointing out the major distinction in their work. He sees himself as a nature poet, while Norman Lindsay’s work was ‘based in love or sex, whatever you like to call it – I was based in nature, and all my poetry starts there, I would think simply because I had a boyhood in the country in New Zealand, and this is where you form your outlook.’ Stewart never really wrote about sex. He tells Semmler, ‘The wonderful bit in Tom Jones – somebody’s got one of the girls in the bedroom and Fielding says merely, “As nothing in the least out of the ordinary occurred, I shall not say anything more about it” – so bloody marvellous, you know – there’s the whole of Lawrence, “Nothing out of the ordinary occurred”, and this to me is the civilised mind.’

Through the years of Stewart’s regular visits up to Lindsay’s house, Springwood, the two men would often talk about nature. Lindsay loved it as much as he did, but not as actively. He was, as Stewart described him, a ‘pedestrian’, i.e. not keen on bush walking.24 Stewart, on the other hand, was happy to spend hours in the bush, examining flora and fauna, and then writing his jewel-like nature poems that seem very often to distil the essence of whatever living being had taken his attention.

‘Yeats laid down what’s pretty well the perfect rule,’ Stewart tells Semmler, ‘and this is use the natural words in their natural order …’

W.B. Yeats was an early hero, and Stewart’s poetry, particularly his later, more lighthearted work, shows that this ‘perfect rule’ is one he adhered to. The poems may today seem old-fashioned, with their emphasis on rhythm and rhyme, but the language is always natural, with no poetic contractions or forced metaphor. Semmler calls it a ‘catholic attitude to rhyme’, and as a demonstration mentions the pairing of ‘put his foot on’ and ‘mutton’. This is from Stewart’s poem ‘Reflections at a Parking Meter’, a musing on how cars are not only taking over the world but irrevocably changing human nature. The words he refers to are in the verse:

Some saw the true position quite reversed;

The car, they said, was just a starter button

That loosed man’s own fierce passions at their worst;

Fired with the chance it gave he stamped his foot on

His own accelerator in a burst

That knocked his fellows down like so much mutton.25

Another poem Semmler wants to discuss is a piece from Stewart’s book Rutherford (1962). It is ‘Fence’, an ironical and humorous observation of suburban life, one of several observational poems that Semmler thinks are ‘quite unique in Australian poetry, because they are somewhat odd in a Raleighian sense’.26 By this he means they are lyrical, incisive and direct, with no obfuscation of meaning.

‘Fence’ is, it seems, about an actual broken fence that stood between the Stewarts’ house and the neighbours, whom he calls the Hogans. The second and fourth verse of this nine-stanza poem read:

For fence is defensa, Latin; fence is old Roman

And heaven knows what wild tribes, rude and unknown,

It sprang from first, when man first took shelter with his woman;

Fence is no simple screen where Hogan may prune

His roses decently hidden by paling of lattice

Or sporting together some sunny afternoon

Be noticed with Mrs Hogan at nymphs and satyrs;

…

It is not wise to meet the Hogans in quarrel

They have a lawyer and he will issue writs:

Thieves and trespassers enter at deadly peril,

The brave dog bites the postman where he sits.

Just as they turn the hose against the summer’s

Glare on the garden, so in far fiercer jets

Here they unleash the Hogans against all comers.

At the end of the poem, the neighbours nail up the broken fence ‘so that Hogans are free to be Hogans/And Stewarts be Stewarts and no one shall watch us scorning …’27

Douglas Stewart gives no indication of what he thinks of Semmler’s comparison of his work to Sir Walter Raleigh’s. Perhaps he knows that Raleigh ended his colourful, tobacco-championing life at the scaffold. Raleigh was not a man given to sitting alone in garrets writing verse – he was an explorer, spy and innovator – and, by today’s terms, also a colonist and murderer. When he was hung, it was to appease the Spanish after a particularly bloody episode in South America.

There are other poets Semmler suggests as influences on Stewart’s work, either in individual poems or more widely. He tries and fails to get Stewart’s admission on the influence of John Donne or that of South African Roy Campbell, and, closer to home, of Stewart’s close friend Kenneth Slessor. This may have irked Stewart a little, though he would have been well aware this is the bread and butter of the literary biographer. Once a connection is found, an influence confessed to, then riches are opened up, and the biographer can spend pages teasing them out.

Semmler is particularly interested in Stewart’s ongoing fascination with New Zealand. Earlier biographer Nancy Keesing had seen Stewart’s love for the country of his birth as a great strength. She wrote: ‘In stressing Stewart’s citizenship of two countries, it is also important to make it plain that in becoming a major interpreter of Australian landscape he has not rejected New Zealand: rather … his continuing preoccupation with two landscapes enhances his interpretation of both.’28 Semmler asks: ‘The poem “Rutherford” – was this some sort of loyal New Zealand orientation, or you know, is it –’. Stewart interrupts: ‘No that was by God’s grace that he happened to live in my own part of Taranaki really. No, I was interested from that metaphysical period we’ve been talking about, which led inevitably to a study of evolution and to how much truth there could be in the theory of evolution, and was there not something more behind it which was worked out in the poem called “The Peahen”.’

‘The Peahen’ explores the evolutionary theory that it is the dowdy female of the species that creates the splendid male. She does this by preferring the males that first begin to evolve the colourful feathers, and that as the generations spin around, the male becomes more and more glorious, and more desirable to the henbird, whose kind Stewart dubs ‘that most poetical poultry’. This is natural selection. But the poet concludes:

It could not be sufficient explanation;

And if it were, what of the peahen’s mind

We’d proved responsible for his creation?

Instinct or taste in her was so refined

That she who had made him perfect sought no sequel

Must deep within her clearly be his equal,

Her sensibility glorious as his plumage.

Could it be so? That dull, drab miserable bird?

We viewed her with new respect; we paid due homage;

But sometimes thought, whatever part she had played

In bringing that blazing splendour out of the dark,

Some utterly unknown principle was at work.29

The biographer is not distracted by the subject of natural selection and presses on with his question about Rutherford: ‘It wasn’t an act of New Zealand faith in other words.’ Stewart replies, ‘No not at all – it was just so useful that it all fell into my hands because I could do the New Zealand stuff without trouble.’

Semmler also pushes him on whether ‘Worsley Enchanted’ from Sun Orchid (1962) is part of an Antarctic fixation. Stewart interrupts him, but is seems Semmler is going to assume that this too is part of his subject’s New Zealand loyalty.

Worsley was the New Zealand navigator of Shackleton’s ill-fated voyage to Antarctica in 1914–16. The ship Endurance became frozen into the ice and the crew made a difficult and challenging trip overland, dragging their lifeboats after them. Eventually, under great duress, they sailed to Elephant Island and from there a small group made it to safety at Georgia. Both perilous voyages were navigated by Worsley. The men on Elephant Island were later collected, and all owed their survival to this extraordinary New Zealander. In recent years he has had a revival. He is the subject of Leanne Pooley’s feature-length documentary Shackleton’s Captain (2012), and is the subject of a dramatised mini-series Shackleton (2002), which stars Kenneth Branagh in the title role. In the 1920s and 30s, Worsley wrote books about his experiences on the Endurance. Stewart’s generation, as boys, read these books and regarded Worsley as a hero. Semmler’s sense that Stewart’s initial curiosity about the story was seeded in his New Zealand childhood was probably right. Certainly the poem is a stellar work, almost filmic in its conception.

From boyhood heroes, acknowledged as such or not, Semmler moves on to humour and tolerance. He points out that the early poems had no humour at all, and that Stewart discovered it as he got older. He quotes Stewart as saying, ‘Tolerance, the tolerance of maturity is not necessarily to be preferred to the romantic ardour of youth …’ As this interview is taking place, the so-called ‘youth culture’ that will come to dominate Western mainstream entertainment for decades is still in its infancy. The legacy of the 1968 Paris riots, of flower power, free love and long-haired hippies is daily more visible. Stewart, with his great curiosity for human behaviour and foibles, and with his ear to the ground for new writing by new writers, will be as aware of it as anybody. One of the last things he will ever say to his daughter Meg will be, ‘The world is for you young people now.’30 Perhaps his statement about tolerance and maturity is further bolstered by an awareness that many writers, composers and artists do their best work before the onset of middle age. At any rate, Stewart agrees with his biographer, and remarks, ‘I think if you’re going to continue writing at all you’ve got to become more tolerant and philosophical.’

Semmler returns to the influence of nationality, with regard to the Birdsville Track poems, which are without exception nature poems. He tells Stewart how much he has always admired them, and asks, ‘[I]s this a sort of gesture of the New Zealander to Australia, now becoming an Australian that you are going to write this sort of classic sequence with an Australian background?’ Once again Stewart plays it down, impressing upon Semmler his long interest in his adopted country. ‘No, it wasn’t like that – I have always had a curiosity about Australia which you see in the first poems, just discovering bits of it.’

Elsewhere, Stewart is less guarded about his sense of displacement. There is a passage in The Seven Rivers where he describes coming for the first time to Duckmaloi, a place he would visit many times to fish. ‘[T]he first time I saw the place it gave me the horrors. The trouble was, I was a newcomer: doubly a newcomer, for I had not been long in Australia, and I had never before stayed at the guest house from which we fished. It takes a few years to learn to cherish the more formidable peculiarities of Australia; and it is a truly terrible experience to arrive for the first time at any guesthouse, even so kindly an abode as was the Richards.’31 A little further on he writes about how, after some rain in the ‘baked landscape, we saw, simultaneously, three snakes quietly weaving their way across our track. It was good weather for hunting frogs, I suppose; but they looked very much as if they were hunting fishermen. To a newcomer from New Zealand, these were quite an appalling sight.’32

The Seven Rivers has become a kind of classic in Australia, and could well herald a revival in Australian nature writing of the kind that is taking place around the world.

Fire on the Snow, Stewart’s most famous verse play, one that garnered awards and was broadcast in many countries, is about Scott’s famous expedition to the South Pole. Generations of Australian school children studied it, and a phrase from it became part of the lexicon in the way that few phrases from literature do today. Stewart had been told that when young lifesavers at the Sydney beaches go overboard from their surfboats, it is customary for them to say, ‘I am just going outside … I may be some time’ – a line attributed to the doomed Captain Oates. Stewart maintains that he finds this appropriation ‘a curious and unnerving thought’.33 It must also have made his heart swell with pride.

The play had come to the attention of Leslie Rees, assistant director at the ABC, after he saw an excerpt in the Bulletin. He contacted Stewart, then 28 years old and working for the magazine, who told Rees he had ‘no thought of having the work produced’, and that his influences were Auden’s ‘The Ascent of F6’ and T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral, which he may have heard broadcast as early as 1935. Rees championed the play, even though there was some debate as to whether ‘a play by a New Zealand writer about Englishmen in Antarctica was truly Australian’.34

Despite the international success of Fire on the Snow, Semmler tells Stewart his favourite play is The Golden Lover. He asks him, ‘Did you know Maoris well when you were a boy, did you get to know the Maori people at all, or did this come from reading or from firsthand association – I’d be interested to know something about that as a sort of background.’

Stewart replies, ‘Well it is my own favourite play too – I think it’s got more poetry and more laughter than any of the others, it’s more natural to myself. And actually I loved writing it – which I usually don’t.’

This sentiment resonates with one of Dorothy Parker’s most quoted aphorisms about the writer’s common experience of hating the process of writing but loving having written. Meg Stewart, writing as her mother, recalled, ‘It wasn’t the writing that took so much out of him, but the preparation, the intense effort of working it up beforehand, exhausted him. I don’t know how he did it. Such concentration.’35

It is worth quoting at length from the tape transcripts on the subject of The Golden Lover because Stewart seems at once at ease and discomfited by Semmler’s questioning him about his familiarity with kaupapa Māori:

| Stewart: | I did know the Maoris fairly well, but not en masse – they were not common and not frequent around Taranaki when I was there, but you saw them, they were the natural part of your life, just as you see migrants today, you saw Maoris then, they used to come round with kit bags selling white-bait at the door – |

| Semmler: | – but your play seems to show a great knowledge about their mores, their customs, and their traditions and their folklore and so on. |

| Stewart: | Well you grow up with all this in your bones, really. The Maori war, a lot of it, the Taranaki war, had been fought over ground where I went to school, and although I wasn’t interested in those days in the history, you soaked it in. We had Maori boys at school with us and I got quite friendly with them, and when I was working on newspapers I had quite a bit to do with somebody who was about to start another Maori war – we had some amusing nights going out to report these dramatic things and I got friendly at that time with educated Maoris who were providing me with information for the paper and then I did go and live with them for only a short while, perhaps two or three weeks or a month or something, in North Auckland when I was carrying a swag up there for some ungodly reason. And a lot of the feeling I got from them, from living with these people, got into the play. But it’s just a general feeling for New Zealand, the Maoris were part of the tradition, and from reading – I don’t think I took Maoris and their culture up consciously in those days, but I’d been to Rotorua – everybody made a pilgrimage to Rotorua – they had dances and songs and Hakas, and you’d pick up something of their legend. Matter of fact when I wrote the play I was reading Cowan’s fairy folk tales of New Zealand for the story of Hinemoa and Tutanekai which is an entirely different legend, much better known than the one I used … And I just dropped onto this other one and, well it hit me like a blinding light, it was just the one I was ready to write. |

If we are to cast a contemporary light on this, as opposed to Stewart’s blinding light, we could truly get our collective knickers in a knot. Earlier I discussed Ruth Park’s The Witch’s Thorn, which suffers from the incipient and highly damaging racism of the time. Top-ranking New Zealand writers of that period had no cultural anxieties regarding the creation of Māori characters. In contemporary New Zealand, non-Māori writers are discouraged from writing about Māori. This is understandable, given the sometimes painful errors made by Pākehā writers, but it has resulted in the peculiar phenomenon of a raft of books over a period of decades that completely ignore the very presence of Māori. If there were to be a worldwide apocalypse and all that is left for future readers are literary works from the late twentieth-/early twenty-first century New Zealand, survivors could suspect us of an extreme, institutionalised racism – the opposite, in fact, of what we are trying to do.

In the interview, Semmler asks Stewart about the line from The Golden Lover, ‘He is full of his importance and too many eels’, and goes on to ask: ‘Is this typical of the Maori, this sort of suddenly bringing things back to earth with a very prosaic sort of utterance you know, from flights of poetry down to the – well from the gor blimey to the ridiculous sort of thing?’

| Stewart: | Yes I think that would be right – they are people very like the Irish, they’re an eloquent people … they are a humorous, laughter loving people and like the Irish, capable of very quick changes of mood. |

| Semmler: | … There’s a line where it says ‘The dogs came to lick my shame with their tongues’ – do the Maoris talk in images like this – is this their way of talking? |

| Stewart: | I think they would have in Maori, I don’t – never heard them today speak in, except in speeches – no, they just talk the most commonplace talk as far as I know. |

And there we have it, the ‘as far as I know’. In his finished biography, Semmler writes that Stewart ‘had grown up with the customs and traditions of the Maoris well embedded in his consciousness’.36 He is perhaps overstating the case.

I once heard the much-loved British writer David Lodge say that a novelist only needs to know enough about a subject to convince the reader that he/she is an expert. It’s a matter of magic, of sleight of hand, of the right details put in the right places so that the narrative is not bogged down with unnecessary information, nor flying around with no roots in reality. How much Stewart knew of Māori culture before he went to live in Australia is debatable, but what he would have learned of speech patterns and idiom he would have learned directly from Māori friends and associates in Taranaki rather than from books.

His confidence in tackling Māori subjects may have been further bolstered by his friend, poet R.D. FitzGerald, who wrote to him from Rotorua when holidaying there with his young family in 1936:

… what amazed me was the tolerance of you New Zealanders and your lack of colour consciousness. I’ve no colour prejudices myself worth talking of, but I’m so used to them in other people that it almost shocks me to see white girls walking up the street in animated conversation with Maori girls or half-caste men. And when I walk along the road the Maori does not step out of the way of a white man; he expects me to step aside if anything. If they deserve, and I gather they do, this status, good luck to them …37

Such sentiments were often expressed by Australians of the time. Even in the mid-1980s, when I lived in Australia, I would often find myself in conversations with Australians who were unhappy with the ‘Aboriginal situation’ and who would tell me New Zealanders were ‘so lucky with the Maoris’. For FitzGerald, it was not only that appalling treatment of indigenous Australians that would have been on his mind, but the White Australia Policy which didn’t come to an end until after World War II. New Zealanders are sometimes in danger of being unnecessarily smug during conversations of this kind. One glance at our current prison population, homelessness and substance abuse problems tells us that our ‘colour prejudices’ are alive and well.

The Golden Lover was Stewart’s favourite of his dramatic works, equal with Shipwreck, which he completed in 1945. It is certainly one of his most successful, not only in the medium for which it was written but also as a live stage performance. In 1942 it won a national competition held by the ABC for a verse play, a genre that has all but died out. Perhaps the most recent attempt at a dramatic verse work of comparable exposure is British filmmaker Sally Potter’s 2004 film Yes, which is entirely written in iambic pentameter. Viewers were either bored and infuriated, or totally captivated, which is a fairly predictable polarised response to the conceit and high artifice of a screenplay in verse.

A few years before Semmler’s interview with Stewart, The Golden Lover was produced as a stage play across the Tasman. Among Stewart’s papers in the Mitchell Library is a copy of ACT, a magazine published by Wellington’s Downstage Theatre Society. It is the April–June edition of 1967 and cost 2/6. Playwright Bruce Mason is the editor and, it appears, writes most of the reviews. On the front cover is a captioned picture of Timoti te Heu Heu (sic) as Tiki and Shirley Duke as Tawhai, starring in the Maori Theatre Trust production that opened at Downstage, Wellington, on 3 April that year. Other cast members include Don Selwyn as ‘a fine authoritative koro’, Kuki Kaa, Thelma Grabmaier, Harata Solomon, Sue Hansen, Ada Rangiaho, Ray Henwood and Bob Hirini.

It is a phenomenal line-up. The names that leap out here are those of Don Selwyn, one of the most recognisable for mid-late century television audiences, starring in drama and directing film; and Timoti Te Heuheu, revered Ngāti Tūwharetoa leader and statesman. Harata Solomon was a well-known actress, singer, performer and cultural leader. Wi Kuki Kaa’s career on stage and film spanned 30 years and included roles in Geoff Murphy’s film Utu and Vincent Ward’s River Queen. Welshman Ray Henwood, we may safely assume, played the golden lover himself, the patu paiarehe Whana, who tries to steal beautiful Tawhai away from her earthly (and, we are given to understand, fat and lazy) husband Ruarangi.

Mason writes:

The problem is idiom. How to write a lyric comedy based on Maori legend, unable to use the language in which it originated, except for the odd chant, greeting or moan of distress? The lyric impulse of English has not been capable of quite this artless freshness since it was Anglo Saxon; how to avoid an artificially poetic jargon? ... In ‘The Golden Lover’ written … for radio, and now twenty years old, Douglas Stewart opts for a mixture of fern and bracken, striking an idiom somewhere between ‘The Song of Solomon’ and Alfred Domett’s ‘Ranolf and Amohia’, redeemed by wit, some crisp comedy and appropriately earthy imagery …

I hope this doesn’t suggest that at Downstage, the play was anything but a fine success. It was and delighted the audience though I suspect that we all felt it to be half an hour too long. But Richard Campion has shown the town for the second time in a few weeks what he can do with a largely inexperienced Maori cast … so an overlengthy but rewarding evening, suggesting new paths for New Zealand drama. For Richard Campion, another huia feather in his cap.

Alfred Domett was briefly the fourth New Zealand premier, a youthful friend of Robert Browning and a poet himself. His Ranolf and Amohia, a South Sea Day Dream was first published in 1872, following several earlier slim volumes of poetry. Encyclopaedia Britannica says of Domett that his ‘idealization of the Maori in his writings contrasts with his support of the punitive control of Maori land’.38 His reputation was not quite so damaged, or truthful, at the time Mason made the comparison. In Mason’s view, Stewart’s play fitted into an emerging subgenre of Pākehā telling Māori stories, among which Alfred Hill’s Māori opera Tapu (1902) and famous cantata ‘Hinemoa’ left a lasting legacy. Tapu was produced in Sydney, complete with geysers and white cast in ‘brown face’.

Mason neglects to mention that ‘traditional Maori food’ was served before the Downstage performance, most likely at the initiative of the Māori cast.39 Not only would this help the audience to understand the most intrinsic tenet of Māori welcome, it would also have helped them enter the world conjured by the possibly homesick 29-year-old playwright burning the midnight oil in his Kings Cross flat.

I borrow a volume of Stewart’s plays from the library. It has a handsome, restrained cover in yellowing white with a grey tile-like border. Four Plays contains The Fire on the Snow, The Golden Lover, Ned Kelly and Shipwreck, and was published in 1958. The copy was issued seven times from December 1958 to March 1959, the stamps filling half of one of the three columns on the glued-on due-date slip. After that, interest appears to have waned, certainly until the stamping system was abandoned and the computer system took over. Was it never borrowed again until I asked for it to be retrieved from the gulag reaches of the stacks? Leafed into the pages is a 2015 checkout item summary for a borrower with a Māori name. The name seems familiar – I look him up – and there, so is his face. He is an Auckland actor, director and writer, and I have seen him on stage. On the same day he borrowed another book – a volume of five plays by Māori playwrights. The slip marks a page about halfway through The Golden Lover. He might have given up on it, or read to the end. New Zealanders of his generation were taught to look for ‘key words’ in any text, an ill-advised idea possibly related to the fashion of moving away from linear narrative. The key words I imagine snagging his eye are, unfortunately, ‘snoring’, ‘lazy’, ‘fat’, ‘smell’ and ‘shark oil’.

The play begins with the Announcer naming the source of the legend as James Cowan’s Faery Folk Tales of the Maori, and toys with the idea that patu paiarehe really did exist ‘as a fair-skinned red-haired people of different origin from the Maoris … There are Maoris to-day who are proud of patu paiarehe blood in their veins, and who have light complexions and auburn hair to prove it.’40

Until relatively recently there were commonly accepted ideas that white-skinned people co-existed with Māori before British colonisation. Those theories have been rightfully tossed aside, along with even more far-fetched ideas that Māori originated in South America, India and even Greece. In 1947 Norwegian Thor Heyerdahl and his crew famously sailed across the Pacific in a papyrus raft, the Kon Tiki, in an attempt to prove that the Pacific was settled in successive migrations from Peru. The expedition caught the public imagination, especially in New Zealand. This was, after all, a period in which Māori were categorised in the national census as ‘Caucasian’.

After the Announcer has set the scene, beautiful Tawhai rouses her husband, who is snoring. ‘Wake volcano!’41Already Tawhai has both cooked and caught the breakfast, having risen at dawn. She asks him, talking about herself in the third person, ‘I am a good wife? You are pleased with Tawhai?’, before going on to tell him how in the early-morning mist she had seen a man of the faery people.42 She explains how frightened she was, and Ruarangi chastises her for disturbing his breakfast. He is frightened by her story too: the eel he has eaten ‘squirms and bites’ inside his stomach.43 They squabble, accusing one another of laziness, of eating too fast, being too fat, and of jealousy. Not only does Tawhai have an admirer from the world of ‘ghosts, monsters and demons’ but she has been seen keeping company with the warrior Tiki, who is younger and slimmer than Ruarangi.

In the second scene we meet Wera, Tawhai’s mother, and her close friend Koura, who saw Tawhai with the patu paiahere. Wera goes looking for her daughter and finds her asleep in the fern. Koura and Tawhai talk about the faery, with red hair and gold skin, who is as tall as a tōtara tree. As the play progresses there is a little tension created by Ruarangi and Tawhai’s father attacking Tiki as the reason for Tawhai’s frequent absences from her whare. In truth she is spending time with Whana, the patu paiarehe, and in time-honoured fairy-tale style she is at first frightened of him and then wildly in love. In Stewart’s version of the story, Whana is overlaid with the European idea of the incubus. Whana tells Tawhai:

You have dreamed about me. All your life you have dreamed.

I know you, Tawhai. You have had lovers, a husband,

And lovers and a husband they were not to be despised;

But always beyond them, Tawhai, there was a dream.

You lay, I know you have lain, with your lover in the bracken,

You have lain with your husband in the bed of fern in the whare,

But who did you lie with in dreams? With your golden lover!44

Tawhai’s people try to make her rub herself with shark oil in order to put off her handsome suitor. Tawhai refuses, saying she is bewitched already, and runs away back to Whana. There are jokes about Ruarangi threatening to eat Tawhai’s father’s dog, and jokes at Ruarangi’s expense because he is fat and hopeless with the axe, which is presumably a mere or taiaha. The play ends, as the legend does, with Tawhai giving up her lover and returning properly to her husband. There are variants in the means by which this comes about, but the Announcer has told us at the very beginning that the play is ‘a free interpretation’ of the original story as related by Cowan.

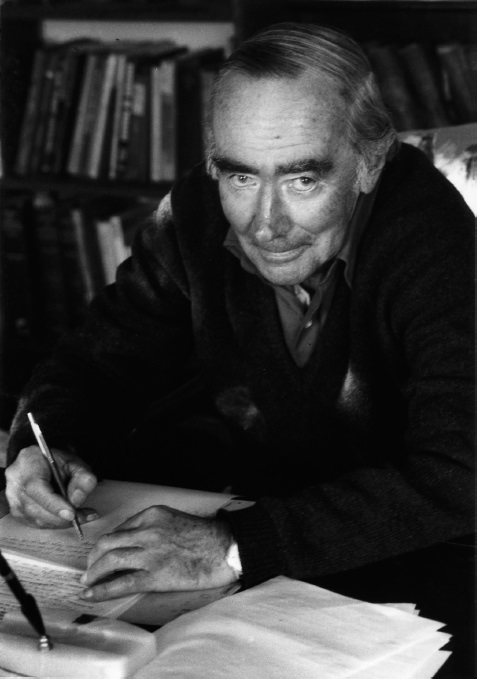

Douglas Stewart at his desk at home in St Ives, 1970s.

Michael Elton photographer, Meg Stewart collection

On that Boxing Day afternoon in 1972, Semmler mentions that The Golden Lover is having a bit of a run with Māori players in New Zealand. Stewart replies:

Yes I’ve been terribly pleased about that. There are a couple of productions in the last two or three years, I think there’s a Maori Theatre Trust over there and they operate sometimes with white groups, there might be one or two white actors perhaps – I think one was an all Maori cast and it had a reasonable press, was I think pretty good, it was essentially, you know, a small production, but it seemed to be the start of something I’d like to see carry on.

Semmler asks if there is a lack of indigenous material of the type that Māori could use to develop traditions in the theatre.

| Stewart: | I have been told by the last people that put it on that this was the only play they could find that expressed the spirit and feeling of the Maoris. It doesn’t mean it’s the only good thing that’s been written about the Maoris, there’s tons of very good short stories and novels but I don’t think much has gone into plays as far as I know. |

There is also, although Stewart doesn’t mention it, emerging writing by Māori, as opposed to about them. He is aware, perhaps, of the publication of Witi Ihimaera’s first collection of short stories, Pounamu, Pounamu, this very year. Ihimaera’s Tangi, the first novel ever published by a Māori writer, will be published the following year, in 1973. He does not know that he was himself one of Ihimaera’s main inspirations to become a writer, after reading the short story The Whare as a boy.

When Semmler asks Stewart about his other New Zealand-inspired play, the unpublished ‘An Earthquake Shakes the Land’, about the land wars of the 1860s, Stewart replies that he never cared very much for it. ‘There’s quite a good soliloquy MacDonald [the central character] makes to his shadow in it, I think. I think the Maoris are a bit statuesque in it; and it was a conscious attempt to analyse war which is too big a subject to analyse anyhow.’

| Semmler: | Is there a sort of thing for the Maoris in it, an indignation at the way the Maoris are treated? |

| Stewart: | Yes there would have been but I don’t think I set out to do that, it was an attempt to analyse war, it was written during the war, I think or just after it, but I think it’s a bit too self-conscious and the Maoris don’t come alive as people. |

Written after The Golden Lover, ‘An Earthquake Shakes the Land’ was produced by the ABC in 1944. A copy of the manuscript is held in the State Library of New South Wales, re-titled ‘Sunset in the Waikato’. As in The Golden Lover, there is an attempt to capture a ‘Māori’ sense of humour. It is one thing for a Māori writer to make jokes at the expense of Māori characters, quite another for a Pākehā to do it. The first joke is on the first page and plays on the fact that the visiting Māori have eaten not only minor chief Kimo’s pigs but are starting on the matting of the whare. This is not just unlikely; it is also highly offensive to Māori. Kimo’s first speech of any length is not humorous, but full of angst and despair. He is referring to land he sold to MacDonald, a Scots settler trying to wrest a farm from the bush on land he has procured from Kimo.

KIMO: You gave me tobacco, and I have smoked the tobacco;

You gave me rum, and I drank too much and was sick;

You gave me flour, and I have eaten the flour,

You gave me clothes, and now they are all holes;

You gave me blankets and now they have worn so thin

That even the fleas are cold. I gave you the land,

And the land is still there; nobody eats the land,

Nobody smokes it or drinks it, it doesn’t wear out,

It stands where it is for ever. I was a fool.

You have the land, and all I have left of the price

Is the tomahawk and the gun.45

MacDonald has a Māori wife, Ngaere, and a baby. We are shown MacDonald stopping Ngaere from drinking whiskey, not because it’s bad for her, but because it’s a man’s drink. MacDonald is dour and hardworking, a kind of everyman settler, not based on any individual. He believes the wars have devastated the Waikato, and thinks of his unloved baby as a ‘piccaninny’.

When Ngaere is questioned about her child, she answers:

He is my pakeha baby, MacDonald’s baby.

The Maoris are finished. They talk and talk at their meetings,

But they all died years ago. New Zealand belongs

To the white man now. I belong to a white man.

And you, little sleepy, New Zealand belongs to you.

You will live in this house, you will have MacDonald’s farm,

It is all for you, these hours and years that he works,

Sunrise to sunset, making a farm for his baby.

Pākehā writers of the 1940s tended to sympathise with the pioneering classes and gave characters such as Ngaere a sense of total defeat. After MacDonald tries to trade his wife and child in return for keeping his land, Ngaere takes up with Kimo, whom she has always loved.

A warrior called Rewi advises Kimo to get MacDonald off the land and take it back for his tribe. MacDonald has other ideas:

I’ll never go.

I made this farm. Made it with my hands and my sweat.

I’ve sunk my life in it. I’ve grown a part of myself

In every pine and fruit-tree I’ve planted.

I’ve ploughed a part of myself into the ground

Whenever I’ve turned a furrow. My blood’s in the grass.

The wheat grows out of my body. Would I leave all that

Because a few savages dance a dance in the night?

In the background, off stage as it were, the building of the Great South Road is going ahead, and Kimo is only too well aware that it will bring soldiers from Auckland. Among the chiefs, Rewi (Ngāti Maniapoto) wants to fight, Tamihana (Waikato) and Te Wherowhero (the future Māori king) do not. They are persuaded to go to war by MacDonald coming to tell them that Governor Browne is to be replaced by Governor Grey: ‘The man of peace, the friend of your people.’ Kimo is present when Grey meets Tamihana. In Rewi’s absence, Kimo tells Grey, ‘Next time you come to the Waikato, bring the soldiers.’

As the war begins, Rewi sends Kimo to collect Ngaere and the child and bring them back to the tribe. This is when MacDonald gives his soliloquy, which reads, in part:

Night. And a man alone. And the times bad.

A lamp and a bottle and a shadow. Shadow my lad,

Will you have a drink with me, Shadow? Drink with MacDonald,

For he drinks alone this night.

The next day he goes to the village with his gun to try to reason with the chiefs, but is shot by Māori warriors. It is Kimo who kills him, presumably because MacDonald is the one Pākehā who has damaged him more than any other.

To create crowd scenes, the play uses the convention of VOICE ONE, VOICE TWO, etc. In the final scene, we hear from soldiers with accents hailing from various parts of the United Kingdom. A Scottish accent has the last word, which may be read as an attempt to justify the war.

… Those brown gigantic men towering on the hill –

The sun stood here! The sun came out of the sky

And stood for three days on Orakau. Now it is dark,

No light, no laughter, no war-song, only the dead.

Yet something remains. The dark earth glowing, glowing!

Men will come here and fill their hands and their hearts

With light forever. They have made this hill a sunset.

(Haka, distant, fading)

No wonder Stewart had mixed feelings about this play, but there is something to admire in his attempt to dramatise the land wars at a time when few New Zealanders knew about the conflict, let alone based literary or artistic works on it. He was in some respects well ahead of his time in that he valued our stories over and above those he could have written centred further afield.

One of the final questions Semmler asks is about Stewart’s love of Australian and New Zealand landscapes and animals. He says, ‘There is to me a sort of simple and loveable way in which you write about these rivers and the countryside and so on, and I suppose it’s – do you ever get a pulling apart, a dichotomy thing between your love for the Australian countryside and your memories of the New Zealand countryside, or do the things coalesce in your thinking and your love of the countryside generally?’

Stewart answers, ‘I don’t think I have any nostalgia at all for New Zealand now – it seems like, you know, a fairy tale to me it’s so long since I lived there, and when I go back it all seems like something you dreamed … after a few years, you know I used to think it took about 10 years to get used to Australia and after that I think you just become Australian.’

Where is Margaret as the interview finishes? Perhaps she is in her studio painting, or perhaps she is outside. A poem that displays not only Stewart’s impressive gift as a poet but also his great love for his wife describes her coming in from the garden. After Margaret’s death, Meg has the poem etched on her mother’s gravestone.

My wife, my life, my almost obligatory love

Heaven forbid that I should seem your slave,

But perhaps I should say I saw you once in the garden

Rounding your arms to hold a most delicate burden

Of violets and lemons, fruits of the winter earth,

Violets and lemons, and as you came up the path –

Dark hair, blue eyes, some dress that has got me beaten –

Noting no doubt as a painter their colour and shape

And bowing your face to the fragrance, the sweet and the sharp,

You were lit with delight that I have never forgotten.46

When the interview is finished, Semmler goes home with the tapes. He works away on his book, and after many trials and tribulations the biography is published by Twayne in 1974.

In September 1975 Douglas Stewart writes to Semmler: ‘The book is certainly getting a wonderful run. In fact, if Twayne will send out review copies, it might be worth trying to continue the run in New Zealand. I get attacked a good deal over there, except for The Seven Rivers, but that doesn’t trouble me.’47

I think it did trouble him, but not overly, not enough for him to lose sleep or fall into a depression. Douglas Stewart was far too level-headed for that. He did know, however, as many of us have learned since, that it is a rare artist or writer who produces work that straddles the Tasman.

In 1982, reviewing Springtime in Taranaki, historian Michael King wrote:

Douglas Stewart is one of New Zealand’s forgotten literary pioneers. Though he has lived in Australia for more than 40 years, he was one of a small group of authors who set in motion a revolution in New Zealand writing in the 1930s. His New Zealand work included poetry, short stories and at least one play, one of the first New Zealand ones broadcast on radio.48

That could be the last word on Douglas Stewart. His close friendship with and/or support of writers like Eve Langley, Rosemary Dobson, Ruth Park, David Campbell, Gloria Rawlinson, Kenneth Slessor, R.D. FitzGerald, Judith Wright, Frances Webb, Mary Gilmore, A.D. Hope, Thomas Keneally and Christina Stead, to name only a few, was instrumental in creating twentieth-century literatures on both sides of the Tasman. However, I think the last word belongs to Stewart himself. In an interview with Geraldine O’Brien in 1984, a year before his death, he talked about the long three years it had taken for his autobiography to find a publisher.

‘It was a comedy, really,’ said Stewart, when asked about this. ‘You see publishers believe Australians won’t read about New Zealand and in New Zealand I’m not known or else wrongly thought an Australian!’49