I WAS WALKING ROSE of Sharon in the courtyard beneath the branches of that big shade tree the next morning when Nacho and Anibal came running over.

“Here. See,” Nacho said, pushing a long sheet of paper at me. “Mañana. You ride Bad Boy. Tomorrow, race number three.”

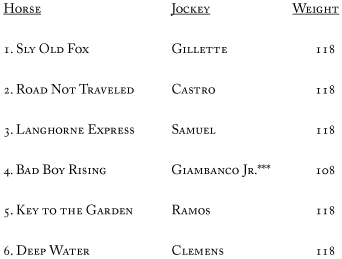

It was the entries for the next day’s races, and there was my name listed as the jockey for Bad Boy Rising, with three asterisks next to it.

3RD RACE

PURSE: $2,400

6 FURLONGS, (CLAIMING $2,000)

FOR 3-YEAR-OLDS & UP

I felt six feet tall as I finished walking the last of those laps with Rose of Sharon.

“You should be down-on-your-knees grateful. This is a helluva opportunity,” Dag told me later at the barn. “The winner gets sixty percent of the purse money, and the jockey ten percent of that. You could make a hundred and a half for about a minute and fourteen seconds’ worth of work. And that’s the cheapest purse money we run for around here. Now see yourself riding all nine races, every day. Start to add up that scratch.”

“I appreciate it. I’ll do the best I can,” I said, with Cap’s warning about Dag creeping into my brain.

“I know you will, Gas,” said Dag, taking the toothpick out of his mouth and stabbing at the air between us.

“What are these three asterisks next to my name for?” I asked.

“Well, one asterisk would mean you’re a bug boy. Three says you’re a triple bug boy—the lowest of the low in a jockey’s career. You got no real experience, and to even make it a race, the other jocks have to spot you ten pounds of weight. But if either you or the horse you’re riding has got any talent, it can be a big advantage.”

That’s when El Diablo came over and stood at my shoulder.

“Satan himself is gonna give you some pointers on how to ride for me,” said Dag.

“Four o’clock, I meet you right here, bug,” said El Diablo in a disgusted voice, like Dag had forced him into it.

I walked away still feeling great, except for the parts about me being tutored by El Diablo, and being called a bug. And somewhere in my mind I had a vision of myself squished under the sole of somebody’s shoe.

“Oh, and Gas,” Dag called after me. “No matter what you might hear about me from certain people at this racetrack, don’t forget, I’m the only one who’s taking care of you.”

That afternoon I went over to the racetrack. I watched the jockeys parade their horses before every race, dressed in the different colored silks of each horse’s owner.

People in the grandstand would yell all kinds of things to them:

“Go get ‘em, Jorge! Bring this one home! You’re my boy!”

“Use that whip, Chop-Chop!”

“I lost a fortune betting on you, Gillette. And every time I bet somebody else, you beat me, you bastard!”

“You on the number six horse, you’re a bum with a capital B!”

Sometimes those riders would wink at the good comments or spit on the ground over the real bad ones. But they mostly stared straight ahead, pretending those people weren’t even there.

It was like they were little supermen, and nothing anybody said could touch them. That’s how I wanted to be.

Nobody in that crowd had the guts to climb aboard a 1,200-pound Thoroughbred like those jockeys did, driving them through tiny openings between horses that could close up in a split second. And even if somebody there did, they were probably too big and heavy to race-ride.

It was just after three thirty when I watched the horses in the fifth race go flying past. With the sound of their hoofbeats thundering in my ears and a streak of bravery running through me, I walked up to the first pay phone I saw to call Dad.

It had been five days since I left, and I had to know what he’d say. Even if he put me down, like I knew he might, I had that jockey’s license I could hold over his head, without telling him where I was.

I listened to the operator’s voice and to a dollar forty in change slide through the coin slot. Then, with my heart pounding, I got connected and heard the phone ring in my house.

Ring … ring … ring …

After three rings Mom’s voice used to pick up on the answering machine. For months after she got killed, it still did.

“You’ve reached the home of the Giambancos—Gaston, Maria, and Gaston Jr. Leave a message at the tone. We’ll get back to you soon, and have a terrific day,” she’d say.

Our last name always sounded like music out of Mom’s mouth—“Gi-am-ban-co.”

Last semester, when I didn’t know how I’d get through the day, I’d call home from school just to hear that message. I’d close my eyes, listening to the sound of her voice. In my mind I could always see her galloping a horse at sunset, with the sky a mix of bright blue and orange.

Then late one night the phone started ringing, and neither Dad or me got to it in time. Her voice came on. Dad was so angry to hear it that he slammed the answering machine with his fist, breaking it in two.

And the last trace of her was gone for good.

I let the phone ring at least twenty times that afternoon from the racetrack, but Dad never answered and no message came on.

Before I hung up, I dropped my face into my chest to hold back the tears and stop the feeling that there was no place left for me anywhere.

When I got to Dag’s barn, El Diablo was already there, sitting on a bale of hay with a whip in one hand and an open can of beer in the other.

Nacho, Rafael, and Anibal were there too, for the horses’ four o’clock feeding.

“This your horse now, bug,” said El Diablo, standing up and slapping at that bale of hay with his whip. “Climb on.”

I felt stupid, but I did it anyway.

Nacho and his brothers were already grinning at me.

“First, starting gate. You break a horse from there? Ever?” El Diablo asked.

I shook my head.

“It called iron monster, ‘cause you don’t know what a horse do inside there. They can get scared in that tight space—the size of a phone booth. They turn loco on you,” El Diablo said. “Keep your horse leaning against back doors, no the front. So he no flip backward and come down on top of you. Crush you. Snap your spine.”

I leaned all my weight back.

“RINNNNNGGGGG!” he shouted in my ear, like the sound of the bell on the starting gate when the iron doors spring open.

My heart jumped, and my weight shot forward.

“Now you go from the gate. Push with your arms. Pump hard. Use your legs for balance,” he demanded, with his face two inches from mine, and the smell of beer heavy on his breath.

I was pumping away when Rafael came over with a handful of feed and offered it to my hay bale.

“No fucking joke!” snapped El Diablo, raising his whip toward Rafael for a second.

He turned back to me and said, “Bug, you learn to ride right or you kill somebody out there. Somebody with kids, you know. I ride a million times better than you, and I kill my own brother on the track in my country—Peru.”

Then El Diablo poured some beer into the dirt, watching it seep into the earth.

“That’s for him—mi hermano,” El Diablo said. “Por el muerto. For the dead.”

“How’d it happen?” I asked, cautious.

“How?” he answered, stopping to take a slug of beer. “His horse break a leg on the first turn. So my brother jump off. He lying on the ground, but my horse no see. Steps on him. Puts its hoof through his skull. That’s how!”

I just stared into his glowing eyes.

“I know right away he dead. But I finish the race, not to face it for another minute. I beat my horse with the whip till somebody take it away from me. That’s when they give me this name—the Devil.”

“But it was an accident,” I said.

“That’s what I say to my ma-ma when I tell her how I kill her son. That no stop her tears,” he said. “Being a jockey ‘bout waiting your turn to get hurt, or paralyze, or killed. You know ‘bout those things, bug?”

“I know,” I answered.

“What you know?” he exploded. “Pick up you shirt! Pick it up! Show me!”

I started to lift my shirt, and El Diablo yanked it quick up to my chin, feeling around my shoulder blades on both sides.

“Hah! Too clean!” he sneered, pulling up his own shirt and pointing to the bumps beneath his shoulders. “I break each collarbone twice. That’s what happens when you go flying from horse. It’s a badge of honor for riders. I got four. It say I know ‘bout being jockey, ‘bout what can happen. You got none, bug. You know nothing. You no even got a pair of leather boots. You ride in joke sneakers your ma-ma buy for you.”

I was somewhere between being ready to break down bawling and wanting to fight. Then I thought about those jockeys on the racetrack and how they seemed bulletproof to all that shit people said to them.

That’s when Nacho yelled at El Diablo in Spanish.

I heard him say my name, the word “madre,” and “no.”

But El Diablo just laughed him off.

“What else you got to teach me?” I asked, trying to sound strong.

“You know how to use this?” he came back, shoving the whip at me.

I closed my hand around it, and the inside of my palm started to burn.

“Prove to me,” said El Diablo.

I hit that hay bale as hard as I could, still pumping with my other arm.

I could hear the swoosh of air and almost feel the whip’s crack.

“Now, switch whip to your left hand,” he ordered. “That surprises horse. Lets him know you mean business.”

But I didn’t have nearly as much strength from that side.

“Harder! Hit harder!” he hollered, grabbing my left arm and squeezing until it hurt.

Then he swung my arm up and down, again and again, until I thought he was going to break it off.

But I wouldn’t give in or tell him to stop. I just stared right through him.

Nacho and his brothers came rushing over, pulling El Diablo off me, screaming, “Para! Para! No!”

El Diablo just shoved the three of them to the floor, with the horses in the barn raising their voices too.

I jumped off that bale of hay and stuck my chest out in front of his, with every muscle in my body trembling.

“Back off!” I shouted in the strongest voice I could find.

Then he looked into my eyes, nearly breathing fire, and said, “They take my license for making one mistake. Now I got to beg every year to ride—to be somebody again. And they let you ride, bug. You?”

“But I didn’t do anything wrong,” I said, and it was like a thousand-pound weight was suddenly lifted off my shoulders.

“Forget what I teach you ‘bout riding. You want to be jockey? No make the mistake I make. ‘Cause then you be crushed anyway,” he said. “Lesson over.”

As he left, El Diablo kicked the beer can lying on the ground. And with a stinging welt rising up on my left arm, I went over to where that can had landed and kicked it even harder.

After they got up and dusted themselves off, I walked back to the dorms with Nacho, Rafael, and Anibal.

They were mad as hornets, cursing at El Diablo in Spanish.

“Ve? See this?” Rafael asked me, annoyed, pointing to the bloody scrape on his chin. “This for helping you.”

“Next time, Gas, fight devil you-self,” said Anibal. “So we no get fired.”

Nacho was walking with his head down and hadn’t said a word to me.

Part of me couldn’t stand what those beaners had done. Like I needed them for protection. But there they were, the only ones by my side.

So I wasn’t sure how to act or what to say. And I didn’t know if I could trust any kind of good feelings I had for what they’d done.

“Gracias,” I told them before I pushed it all out of my mind.