INTRODUCTION: A TABLE AND TWO CHAIRS

Levee [lev-ee]: an embankment along a river that prevents flooding during inclement weather.

NEW YORK IS ONE OF THE MOST DENSELY POPULATED CITIES in the world, and yet it can often seem like the loneliest, especially on the subway, where New Yorkers stand and sit shoulder to shoulder every morning and afternoon without so much as making eye contact. The city is too fast-paced, the screens on our devices too absorbing, the press of bodies too disturbing. But in my first weeks in the city, as the news reminded us hourly that we were a country divided, I detected something else: a special restlessness in the air, a desire to break through the commuter glaze and communicate. I wondered, as an artist, listener, and teacher, could I help New Yorkers engage with those around them in a meaningful way?

I positioned myself at the 3rd Ave subway platform on the L train, along with a table, two chairs, a blank book yet to be written in, and a cardboard sign that read “Secret Keeper.” It took about five minutes for a curious passerby to stop and inquire what I was doing. I presented the book and encouraged him to write down any truth that was weighing on him. “The emotional burden of your secret won’t be as heavy for me,” I said. “I’ll help you carry it.”

Within a few short weeks hundreds of New Yorkers had shared with me their innermost concerns. I didn’t take payment, though many kind souls offered; I wanted to show them, and myself, that some good things could be free. The practice taught me to love listening: While many did choose to write down their secrets, the majority of those who stopped by my table really just wanted to talk. I often heard some version of, “This is great! It’s like therapy!” (I assured everyone that I am not a licensed therapist.) The name kept coming up, so I decided to make it stick. On May 22, 2016, I added a “Subway Therapy” sign to the wall behind my setup.

For the next six months, on a weekly basis, I would set up my Subway Therapy office—a card table and chairs—listening to the people of New York. One day I talked to a woman, a recent immigrant, for three hours about her yearning for a community she could trust. She’d been hurt, taken advantage of since her arrival, and though she had a specialized foreign degree, she saw a future here of menial work far below her potential. There was the daring photographer who showed me images taken from inside subway tunnels. (From now on, whenever a train conductor has to slow down because of someone walking the tracks, I’ll think of those images, their sheer beauty, and the way they bring the underground to light.) Another day, a charming and articulate eighteen-year-old told me about how he wanted to develop medications to slow aging, then asked, “Can I talk to you about being black?” And he did.

Though I had started it for the sake of others, the project was changing my own experience too. Riding the train back to Brooklyn each night, I began to consider the fullness of those around me and across from me, the outstanding complexities that made up each life. How thin the barrier could be between those lives and myself—just a matter of invitation. I loved that Subway Therapy allowed me to ask, “Would you like to sit down?” And I loved that most did—even those drawn to the “office” with laughter, snapping pictures—people from every race, religion, sexual identity, age, socioeconomic profile, and many other designations. The one commonality was that each participant was desperate to be heard by someone.

The day before the 2016 presidential election, many people stopped by my table to speak about their apprehension, how scared and uncertain they felt. The following morning was a dreary one for a majority of New Yorkers: a morning of surprise, anger, disbelief, and, for some, elation. A palpable tension coursed through the air. I wanted to extend the reach of Subway Therapy, to multiply the opportunity for spontaneous expression. I stopped by a store on the way to the train to buy extra supplies, remembering how my mother, a grade-school teacher, used sticky notes in her classrooms to get her students to open up.

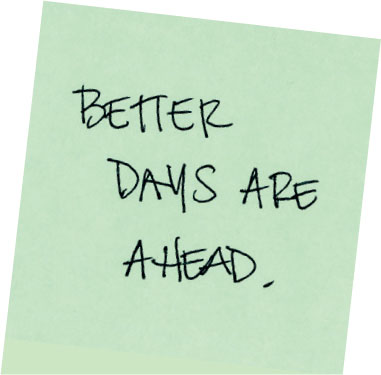

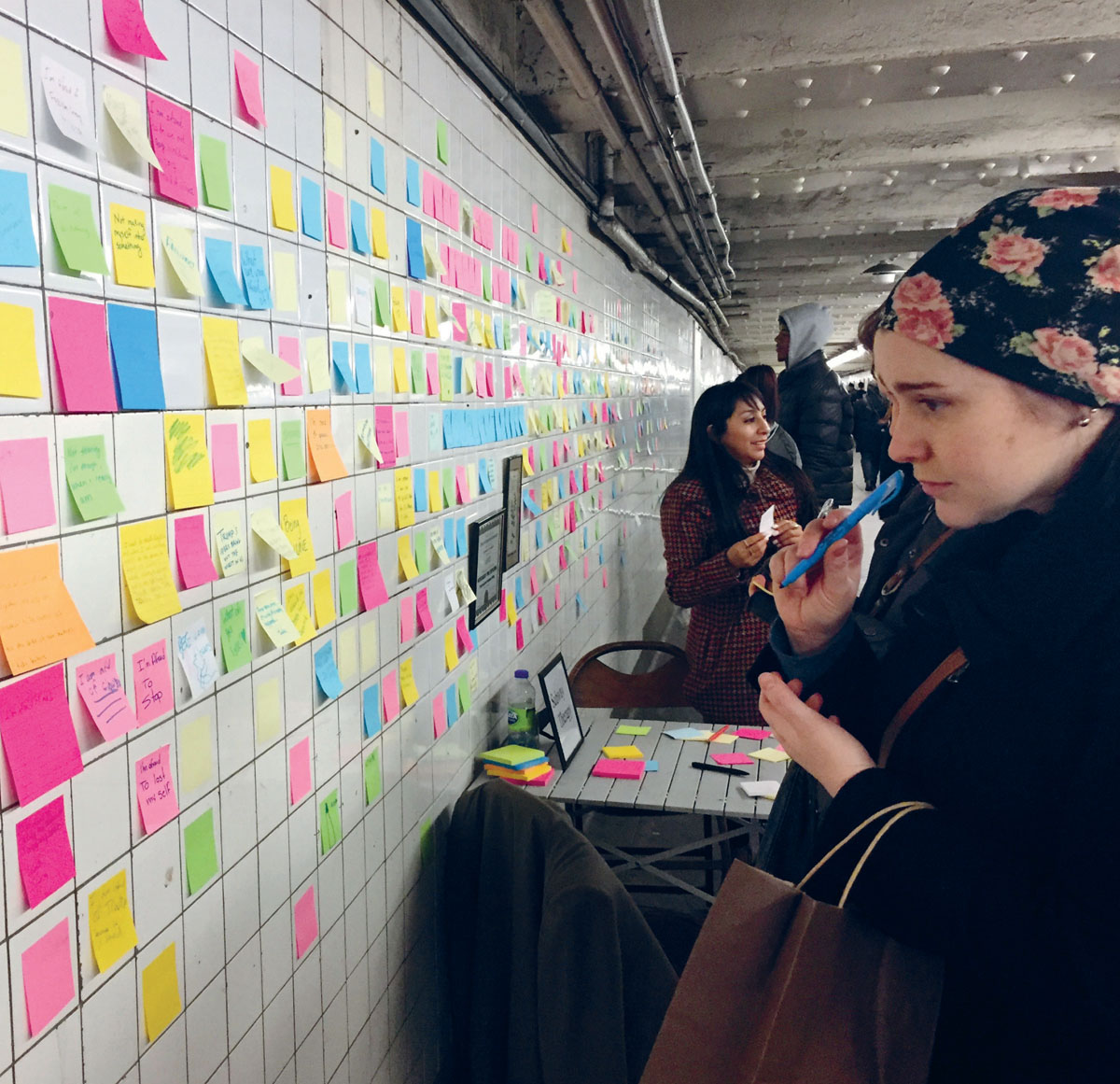

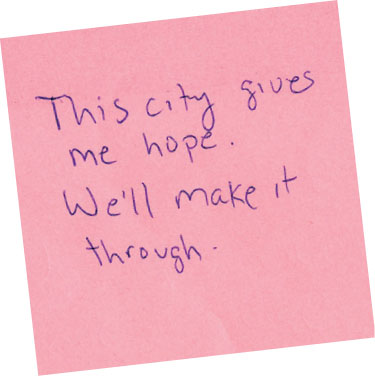

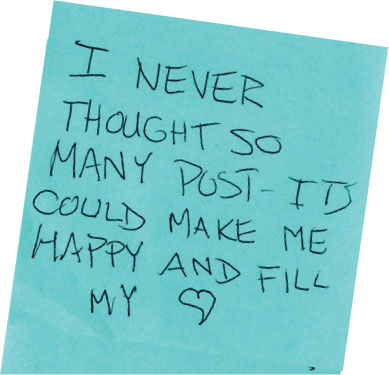

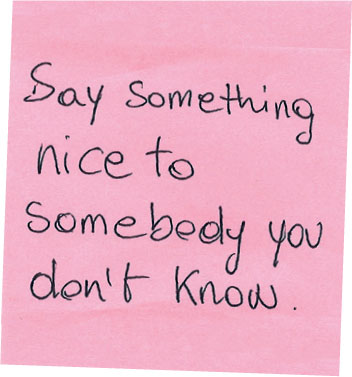

At 2 p.m. I set up my table, chairs, and signs in the bypass tunnel that connects the 6th Avenue L train and the 14th St. 1-2-3-F-M trains, a long, quiet walkway where I knew that I would not be in the way of busy commuters. One letter at a time, I wrote “EXPRESS YOURSELF” on pieces of white paper and taped them up on the wall above my table. Then I picked up a pad of sticky notes and wrote “I’m sad my friends are upset.” I peeled the note off the pad and affixed it to one of the cold white subway tiles above me, leaving the remainder of the pad on the table for others to use. Almost immediately, someone stopped to write. Soon there was a flood of people scribbling around me, some lingering to read the notes left by others. Some would stop to speak; others wrote, read, even wept.

Something was happening. I couldn’t leave, so I called my best friend, Adam, who showed up with a bagful of sticky notes in all colors. Soon news crews arrived to capture footage of the scrum. By midnight there were two thousand handwritten notes on the wall, a mosaic of human emotion.

At the end of the day I wasn’t sure what to do. Would the notes be removed and disposed of if I left them behind? Would they be vandalized, swept away? I felt responsible for them, but also to the people who had left them behind. In my exhaustion, I could think of only one option: I would take the notes down that night and bring them home with me, then put them back up again the next day. Carefully peeling each note from the wall by myself that night made for a strange sort of meditation. At 2 a.m., as I sat alone in the empty tunnel, all traces of the day stowed safely in my backpack, sticky notes were spontaneously spreading like rainbow-colored ivy in other subway stations across the city. New Yorkers were connecting with one another.

Within days, walls of sticky notes popped up in San Francisco, Seattle, Boston, Washington, D.C., Oakland, and other cities around the nation and abroad. Teachers sent me pictures of walls their students had created, others would tell me about sticky note walls in offices, stores, and even on the mirrors of public restrooms. Each morning that followed, a group of friends and passersby helped me put up thousands of notes in the tunnel, and each night new people stopped on their way home to help me collect the originals and the thousands of new notes that had been written that day. I’m eternally grateful for the help of these volunteers of far-ranging political leanings.

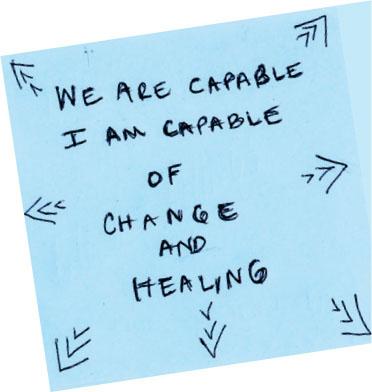

The sticky note project has been called a visual representation of the voices of the people of New York: some confused, some scared, some angry, but so, so many that are loving and hopeful and inspiring and proud. I have seen the notes turn countless strangers writing alongside one another into neighbors, children into their parents’ teachers, and sweethearts into fiancés (several people used the sticky note wall to propose marriage to their beloveds). New Yorkers from all across the political spectrum contributed. And though the wall became a phenomenon around a political event, its power is not limited to political discourse; the wall has presented a larger opportunity for people who would not ordinarily interact or understand one another to connect, feel empathy, and find common ground.

I hope these notes speak to you as they have spoken to me.

A note on my name: I grew up next to a levee in Gilroy, California, and my friends and I would go there often. I loved watching the trickling creek of the dry season transform into a powerful force with the rains. And I loved the steady neutrality of the levee—just there, not stopping the surge but directing it, managing the overflow, many times saving our neighborhood, our homes. One of my goals has been to help people channel strong emotions, and I chose the name Levee as a way to embody this.