The Slav is one of the most popular lines of the Queen’s Gambit. Black secures his centre with 2...c6 and intends to develop his light-squared bishop before playing...e6.

We have decided to recommend that White plays the main line, viz. 3 ♘f3 ♘f6 4 ♘c3 and meets 4...dxc4 with 5 a4. White’s sound, sensible plan is to regain the pawn and seize territory in the centre. In turn, Black has control of the b4 square and chances of sniping at White’s centre. As Nigel Short commented, ‘It’s quite a good opening.’

Black has various responses to 5 a4. Some of these, such as 5...♗g4 and 5...♘a6 are rather provocative, and are considered in the next chapter.

The main line is 5...♗f5, with which Black establishes a grip over the e4 square. The battle will focus around White’s attempts to establish a pawn on this square, gaining time on Black’s bishop, without making too many concessions.

Here we shall focus on plans for White involving ♘e5, ♗g5, ♘xc4 and eventually e4, rather than get bogged down in the hot theoretical lines following the piece sacrifice 6 ♘e5 e6 7 f3 ♗b4 8 e4 ♗xe4. However, we suggest that this line should be borne in mind for comparison purposes; naturally if White can get a superior version of this line, then there is no point avoiding it.

En route to the main lines, we shall deal with various deviations for Black, including, after 5 a4 ♗f5 6 ♘e5, Black’s alternatives to 6...e6.

Game 18

Vladimirov – Engqvist

Gausdal 1990

1 d4 d5 2 c4

2 |

... |

c6 |

3 |

♘f3 |

♘f6 |

Black has also tried 3...dxc4 intending to hold on to his pawn with ...b5. The complications in this line have so far favoured White: 4 e3 b5 (4...♗g4 5 ♗xc4 e6 6 h3 ♗h5 7 ♘c3 ♘d7 8 0-0 ♘gf6 9 e4 left White with a pleasant edge in Ribli-Ljubojević, Amsterdam 1986) 5 a4 e6 6 axb5 (Loginov suggests 6 b3 ♗b4+ 7 ♗d2 ♗xd2+ 8 ♘fxd2 a5 9 axb5 cxb5 10 bxc4 b4 11 ♕f3 ♖a7 12 ♕g3 ♘c6 13 ♕xg7 ♕f6 14 ♕g3) 6...cxb5 7 b3 ♗b4+ 8 ♗d2 ♗xd2+ 9 ♘bxd2 a5 10 bxc4 b4 11 c5! ♘f6 12 ♗b5+ ♗d7 13 ♕a4 0-0 14 ♘e5 ♗xb5?! (14...♘d5 15 ♘xd7 ♘c3 16 ♘xf8 ♘xa4 17 ♘xe6 fxe6 18 ♗xa4 ± Malaniuk) 15 ♕xb5 ♕c7 16 ♘dc4 ± Malaniuk-Maliutin, Forli 1992.

4 |

... |

dxc4 |

Black has a variety of alternatives to this move. The most fashionable is 4...a6, which has become important enough to deserve a chapter of its own. The others:

a) 4...♗f5 is premature due to 5 cxd5 (5 ♕b3 ♕b6 transposes to line ‘c’) 5...cxd5 (5...♘xd5 6 ♘d2! Δ e4 ±)6♕b3!±.

b) 4...g6 hopes to reach a Schlechter Variation after 5 e3, but White can play 5 cxd5 cxd5 6 ♗f4 ♗g7 7 e3 0-0 8 h3 with a very pleasant game.

c) 4...♕b6 5 ♕b3 ♗f5 (if Black exchanges, White has useful pressure on the a-file; 5...♘a6 6 c5 ♕xb3 7 axb3 ♘b4 8 ♖a4 ±) 6 c5 and now:

c1) 6...♕xb3 7 axb3 ♘fd7 (7...♘a6 is met by the standard trick 8 e4! followed by ♗xa6, shattering Black’s queenside) 8 ♗f4 f6 9 e3 e5 10 ♗g3 g6 11 b4 (Miles-Bellón, Las Palmas 1980) and although Black has mobilized his centre, White’s queenside play gives him a clear plus.

c2) 6...♕c7 7 ♗f4 (this is another standard trick) 7...♕c8 8 h3 is given as ⩲ in ECO. This is certainly believable, though there have been few practical examples, e.g. 8...h6 9 g4 ♗e4 10 ♘xe4 ♘xe4 11 ♗g2 ♘d7 12 ♘e5 ♘xe5 13 ♗xe5 f6?! 14 ♗h2 ♕d7?! 15 h4! ♕xg4 16 ♗f3 ♕xh4 17 ♗g3 ♕g5 18 ♕xb7 ♖d8 19 ♗c7 ♕d2+ 20 ♔f1 ♕xd4 21 ♗h5+ ♔d7 was played in Burgess-Truus, Võsu 1989. Now after 22 ♗e5+? Black resigned, but White really ought to have found the forced mate in five – we’ll leave this as an exercise for the reader!

5 |

a4 |

♗f5 |

6 |

♘e5 |

♘bd7 |

The move active 6...e6 is covered in the next game.

Another possibility is 6...♘a6 but simple methods suffice to give White an advantage, viz. 7 e3! ♘b4 8♗xc4 e6 9 0-0 ♗e7 10♕e2:

a) 10...♘d7 11 e4 ♘xe5 12 dxe5 ♗g6 13 ♗e3 ♕a5 14 f4 ± Razuvaev-Meduna, Moscow 1982.

b) 10...0-0 11 e4 ♗g6 12 ♖d1 c5 13 ♘xg6 hxg6 14 d5 exd5 15 e5! ♖e8 16 ♗b5 ♗f8 17 ♗xe8 ♘xe8 18 e6 ± Li Zunian-Vaganian, Biel 1985.

c) 10...h6 11 e4 ♗h7 12 ♖d1 0-0 13 ♗f4 ♕a5 14 ♗b3 ♖ad8 15 ♘c4 ♕h5 16 f3 ± Smejkal-Torre, Thessaloniki OL 1984.

6...c5? is overambitious, and gets absolutely demolished by 7 e4!, e.g. 7...♘xe4 8 ♕f3! e6 (8...cxd4 9 ♕xf5 ♘d6 10 ♗xc4 +– Nadel-Margulis, Berlin 1932) 9 g4! ♕xd4 10 gxf5 ♘xc3 11 ♘xf7! winning, or 7...♗xe4 8 ♗xc4 e6 9 ♘xe4 ♘xe4 10 ♗b5+, also winning.

Lobron-Beliavsky, Munich 1994 featured the unusual 6...♘d5? and after 7 e4 ♘xc3 8 bxc3 (8 ♗xc4! +− Beliavsky) 8...♗xe4 9 ♗xc4 ♗d5 10 ♗xd5 ♕xd5 11 0-0 ♘d7 12 c4 ♕e6 13 ♕b3 ♘xe5 14 ♕xb7 ♕c8 15 ♕xc8+ ♖xc8 16 dxe5 e6, Dorfman recommends 17 ♗e3 a5 18 c5 when ‘Black will suffer for a long time’.

7 |

♘xc4 |

♕c7 |

7...♘b6 is also interesting. After 8 ♘e5 e6 9 f3, in comparison to Game 19, White has already captured the pawn on c4 but the black knight is on b6. This should favour White, e.g. 9...♘fd7 (9...♗b4 10 e4 ♗g6 {now 10...♗xe4? is not possible now because of 11 fxe4 ♘xe4 12 ♕d3} 11 ♗e3 a5 12 ♕b3 ♘fd7 13 ♘d3 ♗e7 14 ♗e2 0-0 15 0-0 ± Gelfand-Draško, Tallinn 1989) 10 a5! ♘xe5 11 axb6 ♘d7 12 e4 ♗g6 13 ♖xa7 ♘xb6 14 ♖xb7 ♖a1 15 ♔f2! ♗e7 16 ♕b3 ♖xc1 17 ♕xb6 with a small edge for White according to Tukmakov in ECO.

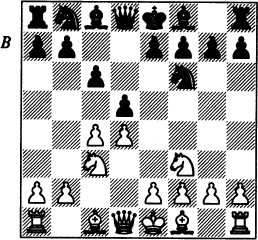

8 |

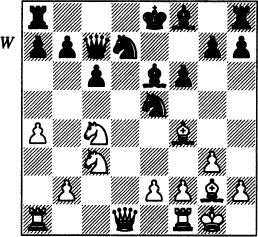

g3! (D) |

|

The best and most logical plan.

8 |

... |

e5 |

9 |

dxe5 |

♘xe5 |

10 |

♗f4 |

♘fd7 |

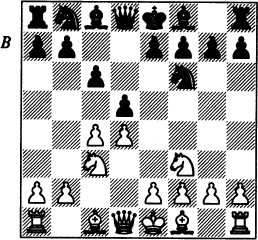

10...♖d811 ♕c1 ♗d6 12 ♘xd6+ ♕xd6 surrenders the bishop pair in return for a very solid position. White can win a pawn with 13 ♕e3 but Black achieves good counterplay after 13...♘g4 14 ♕xa7 0-0 15 ♗g2 ♕b4 16 ♗xe5 ♘xe5 17 0-0 ♘c4 A.Rodriguez-Torre, Biel IZ 1985. Therefore 13 ♗g2 (D) is normal:

a) 13...0-0:

a1) 14 0-0 invites transposition to ‘c’, by 14...a5, while 14...♘fd7 15 a5 a6 16 ♘a4 ♕b4 17 ♗d2 ♕b3 18 ♗c3 ⩲ was P.Cramling-Campora, Biel 1990.

a2) 14 a5:

a21) 14...♕e7 15 0-0 a6 16 ♘a4 ♖fe8 17 ♘c5 ♘g6?! (17...♗c8 ⩲) 18 ♗g5 ♗c8 19 ♘e4 ♗f5 20 ♗xf6 gxf6 21 ♘c3 ± Bagirov-Meduna, Stary Smokovec 1981.

a22) 14...♕e6 15 0-0 a6 (Adorjan-Osmanović, Sarajevo 1983 continued 15...♘g6 16 ♗g5 h6 17 ♗xf6 ♕xf6 18 ♕e3 a6 19 ♕b6 ♕e7 20 f4 ±) 16 ♖d1 (16 ♘a4 ♘fd7 17 ♕e3 f6 ∞) 16...h6 17 ♕e3 ♖xd1+ 18 ♖xd1 ♘fd7 19 ♕d4 ♕e7 20 ♘e4 ♗xe4 21 ♗xe4 and the bishop pair guarantees White an edge; Tukmakov-Agzamov, USSR Ch 1983.

b) 13...♕e7 14 0-0 a5:

b1) 15 ♕e3 ♘c4 16 ♕xe7+ ♔xe7 17 e4 ♗e6 18 ♖fel h6 19 b3 ♘d2 20 ♘d5+! cxd5 21 ♗xd2 b6 22 exd5 ♘xd5 23 ♖ad1 ♘f6 24 ♗c1 ♖xd1 25 ♖xd1 ♖c8 26 ♗a3+ ♔e8 27 ♖d6 ⩲ Mokry.

b2) 15 h3!? is a good alternative, e.g. 15...0-0 16 g4 ♗c8 17 ♕e3 (17 ♗g5!?) 17...♘g6 (17...♖fe8 18 ♖fd1 ♖xd1+ 19 ♖xd1 ⩲ Haba-Trichkov, Lazne Bohdanec 1994) 18 ♕xe7 ♘xe7 19 e4 ♗e6 20 ♗c7 ♖d2 21 ♖ab1 ♖a8 22 ♖fd1 with a wonderful position for White in Vladimirov-Barbulescu, Havana 1986 and Uhlmann-Starck, E.German Ch 1985.

c) 13...a5 14 0-0 0-0 15 ♕e3 (15 h3!? is probably best answered here with 15...♘fd7). Now Black has a choice between two moves:

c1) 15...♘fd7 16 ♖ad1 ♕e6 17 ♕a7 (17 ♖d4 f6 18 ♖fd1 ± Salov-Bareev, USSR 1983) 17...♗c2 18 ♖d2 ♕b3 19 ♖c1 ♗f5 20 ♘e4! ♗xe4 21 ♗xe4 ♕xa4 22 ♗f5 ♕b5 23 ♖cd1 ± Grünberg-Meduna, Sochi 1983.

c2) 15...♘fg4 16 ♕b6 ♕b4 17 ♕xb4 axb4 18 ♘a2 (18 ♘e4!?) 18...♘g6 19 ♗c1 b3 20 ♘c3 ♗c2 21 a5 ♖a8 22 ♖a4 f5 23 h3 ♘f6 24 ♗e3 ♖fd8 25 ♖fa1 ⩲ Browne-Miles, Surakarta/Denpasar 1982.

11 |

♗g2 |

|

Not 11 ♕d4 f6 12 ♖d1 ♗c5 13 ♘d6+ ♔f8 14 ♕d2, which fails to the continuation 14...♘d3+! 15 exd3 ♗xd6 ∓ Engqvist.

11 |

... |

f6 |

If Black doesn’t want to weaken his pawn structure immediately he can try 11...♗e6 12 ♘xe5 ♘xe5 but then White has a comfortable choice:

a) 13 0-0:

a1) 13...♗e7 14 ♕c2 ♖d8 15 ♖fd1 0-0 16 ♘b5! ♖xd1+ 17 ♖xd1 ♕a5 18 ♘d4 ♗c8 19 b4! ♕c7 20 b5 ± Alekhine-Euwe, Amsterdam Wch (1) 1935.

a2) 13...♕a5 14 ♘e4 ♖d8 15 ♕c2 ♗e7 16 b4! ♗xb4 17 ♕b2 f6 18 ♖fb1 0-0 19 ♗xe5 (19 ♕xb4? ♖d1+!) 19...fxe5 20 ♘g5 ♗c3 21 ♕c2 ♗f5 22 ♗e4 +– Capablanca-Euwe, Netherlands 1931.

a3) 13...f6 14 ♕c2 ♗d6 15 ♘e4 0-0 16 a5 a6 17 ♖fd1 ♖ad8 18 ♗e3 ♘c4 19 ♗c5 ♗xc5 20 ♘xc5 with the better chances for White in Timman-Hébert, Rio de Janeiro IZ 1979.

b) 13 ♕d4 f6 14 a5 a6 15 ♘e4 ♖d8 16 ♕c3 ♗d5 17 0-0. Now it isn’t strictly necessary for Black to exchange on e4 immediately, but he will be forced to do so sooner or later:

b1) 17...♗e7 18 ♖fd1 ♗xe4 (18...0-0? fails to 19 ♘xf6+! ♗xf6 20 ♗xd5+) 19 ♗xe4 0-0 20 ♕b3+! (better than 20 ♗e3 ♖d6 21 ♕b3+ ♔h8 22 ♗b6 ♕c8 23 ♖xd6 ♗xd6 24 ♖d1 with only a little edge for White; Browne-Unzicker, Wijk aan Zee 1981) 20...♔h8 21 ♕e6. Black is in severe trouble according to Henley; how should he break the pin?

b2) 17...♗xe4 18 ♗xe4 ♗d6 19 ♕c2 ± Torre-Hübner, Tilburg 1982. White has the bishop pair and can create pressure on both the kingside and the queenside.

12 |

0-0 |

♗e6 (D) |

12...♖d8 13 ♕c1 ♗e6 14 ♘e4! ♗e7 15 a5 a6 16 ♘xe5 ♘xe5 17 ♘c5 ♗c8 18 ♕c3 0-0 19 ♕b3+ ♔h8 20 ♘e6 ♗xe6 21 ♕xe6 ⩲ Taimanov-Ignatiev, USSR 1971.

13 |

b3!? |

|

An interesting idea – White doesn’t want to clarify things in the centre just yet. Before this game White usually tried 13 ♘xe5 fxe5 (for 13...♘xe5 see 11...♗e6) 14 ♗e3 ♗c5 (14...♗e7 15 a5 a6 16 ♕c2 0-0 17 ♖fd1 ♖ad8 18 ♘d5 ± Capablanca-Brinckmann, Budapest 1929) 15 ♕c1 ♗xe3 16 ♕xe3 ♕b6 17 ♕d2 0-0 18 a5 ♕c7 19 ♕e3 ⩲.

13 |

... |

♗b4 |

14 |

♕c2 |

0-0 |

15 |

♘xe5 |

fxe5 |

15...♘xe5 is possible, but White gets the better endgame after 16 ♘d5 ♕a5 17 ♘xb4 ♕xb4 18 ♗d2! ♕xb3 19 ♕xb3 ♗xb3 20 ♖fb1♗c4 21 f4! ♘g4 22 ♖xb7 ⩲.

16 |

♗e3 |

♘f6 |

17 |

♘e4 |

♘xe4 |

18 |

♗xe4 |

h6 |

19 |

♖fdl |

♖fd8 |

19...♕f7 20 ♗g6 ♕f6 21 a5 ♗d5 22 a6 b6 23 ♖a4 ⩲.

20 |

♗f5 |

♗f7 |

21 |

♕e4 |

a5 |

22 |

♕g4 |

♖d6 |

23 |

♖xd6?! |

|

An inaccurate move. White should prefer 23 ♖d3 ♖ad8 24 ♖c1 ⩲. After the text, White went on to win, but this was partly due to the clock:

23...♕xd6 24 ♗c2 ♗d5 25 ♕f5 ♕e6 26♕h7+♔f7

26...♔f8 may be a little better.

27 ♗f5! ♕f6 28 ♖d1 ♗c3 29 ♖d3 ♗d4 30 ♗e4 ♗xe4

30...♖d8 31 ♔g2 ♗xe4+ 32 ♕xe4 also gives White a small advantage.

31 ♕xe4 ♕g6?

A terrible error in time trouble. After 31...♖d8 White’s advantage is only minimal.

32 ♕xg6+ ♔xg6 33 ♗xd4 exd4 34 ♖xd4

The rook endgame is easily won.

34...♖a6 35 f4 ♖b6 36 ♖d3 ♖b4 37 ♔f2 c5 38 ♔f3 c4 39 bxc4 ♖xa4 40 ♖d6+ ♔h7 41 ♖b6 ♖xc4 42 ♖xb7 ♖c3+ 43 e3 a4 44 ♖a7 a3 45 h4 1-0

Game 19

Kamsky – Akopian

Biel IZ1993

1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 ♘f3 ♘f6 4 ♘c3 dxc4 5 a4 ♗f5 6 ♘e5

6 |

... |

e6 |

This is the most popular move. Black will pin White’s queen’s knight, and fight tooth and nail for the e4 square, sacrificing a piece there if necessary.

7 |

f3 |

♗b4 |

The move 7...c5 attacks White’s centre immediately, but in view of a superb piece of work by Van der Sterren, interest in the move has come to an abrupt halt: 8 e4 cxd4 9 exf5 ♘c6 (the piece cannot be recaptured due to the weakness of f7) 10 ♘xc6 bxc6 11 fxe6 fxe6 12 ♗xc4 (there is no good way to keep the knight) 12...dxc3 13 bxc3 ♕a5?! (13...♕xd1+ 14 ♔xd1 ♘d5 15 ♔c2 ♖b8! is the lesser evil – Petursson). Now rather than 14 ♗d2? ♘d5 (14...♗c5!?) 15 ♕e2 ♔f7 16 0-0 ♗c5+ 17 ♔h1 ♖he8 18 ♗d3 ⩲ Salov-Smyslov, USSR Ch (Moscow) 1988, Van der Sterren’s recipe was 14 ♕e2!! ♕xc3+ 15 ♔f1 ♕xa1 16 ♕xe6+ ♔d8 17 ♔e2! ♕xa4 18 ♖d1+ ♕xd1+ 19 ♔xd1 +– Van der Sterren-Petursson, San Bernardino 1992.

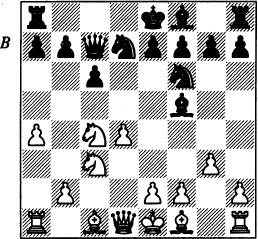

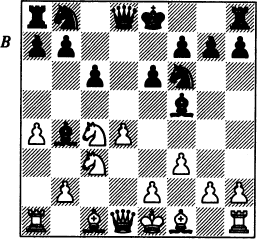

8 |

♘xc4 (D) |

|

The highly theoretical line is 8 e4, whereupon Black sacrifices (8...♗xe4) and the main lines have been worked out beyond move twenty. We would like instead to draw your attention to a calmer method which involves less memory work.

After the text, White is definitely threatening 9 e4 (see ‘a’ in the next note), so Black’s response must take this into account.

8 |

... |

0-0 |

There are a few alternatives, but none to trouble White:

a) 8...♘bd7 is now met by 9 e4, when the sacrifice is unsound: 9...♘xe4 10 fxe4 ♕h4+ 11 ♔d2 ♕f2+ (11...♕xe4?? walks into 12 ♘d6+! – compare the note to White’s 9th move) 12 ♕e2 ♕xd4+ 13 ♔c2 ♗g6 14 ♗e3 ♕f6 15 ♖d1 ± Magerramov-Stratil, Uzhgorod 1988, so Black has nothing better than 9...♗g6 10 ♗e2 0-0 11 0-0 ♘e8 12 ♕b3 a5 13 ♘a2 ♗e7 14 ♗e3 c5 15 d5 ± Vladimirov-Shamkovich, USSR Ch 1967.

b) 8...♘d5 9 ♗d2:

b1) 9...♕h4+ wastes too much time: 10 g3 ♕xd4 11 e3 ♕f6 12 e4 ♘xc3 13 ♕b3! ♘xe4 14 ♗xb4 ♕d4 15 fxe4 ♕xe4+ 16 ♔f2 ♕xh1 17 ♘d6+ ♔d7 18 ♘xf5 +– Mikenas-Feigin, Kemeri 1937.

b2) 9...♘b6 10 e4 ♗g6 11 h4!? (better than the more obvious 11 ♕b3 a5 12 ♗e3 ♘8d7 13 ♗e2 ♘xc4 14 ♕xc4 0-0 15 ♖d1 ♔h8 16 0-0 f5 ∞ Sturua-Mnatsakanian, Tbilisi 1983) 11...h6 (essential since 11...♘xc4 fails to 12 ♗xc4 ♕xd4 13 ♕b3!) 12 ♘e5 ♗h7 13 a5 ♘6d7 14 ♕b3 gives White a large advantage (Botvinnik).

c) 8...c5 9 dxc5 ♕xd1+10 ♔xd1 and now Black should castle:

c1) 10...♗xc5 11 e4 ♗g6 12 ♘b5 ♔d7 13 ♘e5+ ♔d8 14 ♗f4 ♘a6 15 ♘d3 ♗e7 16 ♖c1 ± Browne-Formanek, USA 1982.

c2) 10...♘c6 11 ♘d6+ ♔e7 12 e4 ♗g6 13 ♘xb7 ♘d8 14 ♘a2 ± Beliavsky-Velikov, Plovdiv 1983.

c3) 10...0-0 11 e4 ♗g6 12 ♘d6 ♖d8 13 ♔c2 ♘c6 (after 13...b6? 14 cxb6 axb6 15 ♘db5 White has a safe extra pawn; Henley-S.Pavlović, Lugano 1983) 14 ♗e3 b6 15 ♗b5 ♘a5 (Agzamov-Beliavsky, USSR Ch 1981) 16 ♖hd1 ⩲ Tukmakov.

9 |

♗g5 |

|

9 e4 is dubious here since after the sacrifice 9...♘xe4 10 fxe4 ♕h4+ 11 ♔d2, Black can play 11...♕xe4 ∓ Khapilin-Firsov, Naberezhnye Chelny 1988, since, now that Black has castled, 12 ♘d6 is not check.

9 |

... |

h6 |

This move isn’t entirely compulsory but if Black plays 9...c5 immediately White may later bring his bishop back to a useful square on the c1-h6 diagonal.

10 |

♗h4 |

c5 |

It is tempting for Black to prepare this thrust, but this may only give White time to prepare a response, e.g. 10...♘a6 11 e4 ♗h7 12 ♘e3! (now White is ready to answer...c5 with d5) 12...c5 13 d5 exd5 14 ♗xf6 ♕xf6 15 ♘xd5 ♕e5 16 ♗c4 ♗a5 17 0-0 with the better prospects for White; Lin Ta-Chernin, Lucerne Wcht 1985.

11 |

dxc5 |

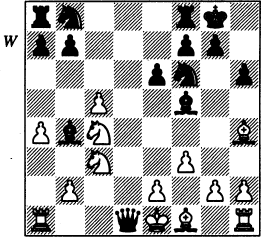

♕xd1+ (D) |

This is better than permitting White to exchange: 11...♗xc5 12 ♕xd8 ♖xd8 13 e4 ♗h7 14 ♗f2 ♗xf2+?! (14...♗b4 ⩲) 15 ♔xf2 ♘c6 16 ♗e2 ♘d7 17 b4! f5 18 ♘d6 fxe4 19 b5 ♘a5 20 ♘cxe4 ± Langeweg-Böhm, Wijk aan Zee 1976.

12 |

♔xd1 |

|

At first sight it seems more natural to recapture with the rook, i.e. 12 ♖xd1, but it will still be a while before White is ready to castle. Moreover Black can activate his light-squared bishop: 12...♗c2 (else the bishop risks being shut out of the game by e2-e4) 13 ♖c1 and now Black’s best chance is an exchange sacrifice, made famous by Beliavsky’s loss in 1986 to Bareev (at the time a little-known, low-rated player):

a) 13...♗h7?! 14 e4 ♘c6 15 ♘d6 ♘a5 (15...b6 16 ♗f2) 16 ♗f2 b6 17 ♖d1 bxc5 18 ♗a6 ♖ab8 19 0-0 ♘b3 20 ♘b7 c4 21 ♗g3 ♖bc8 22 ♘d6 ± Beliavsky-Portisch, Wijk aan Zee 1985.

b) 13...♗xa4!? 14 ♗xf6 gxf6 15 ♖a1 ♗b3 16 ♘b6 ♘c6 17 ♘xa8 ♖xa8 18 e3 ♗xc5:

b1) 19 ♖f2 f5 20 ♘a4 (20 g3? ♖d8 21 ♗e2 ♖d2 22 f4 ♘b4 23 ♔f3 ♘d5 24 ♖hc1 ♘xe3 ∓ Beliavsky-Bareev, USSR Ch 1986) 20...♗b4 (20...♗xa4 21 ♖xa4 ♖d8 22 ♗e2 ♖d2 gives Black a wonderful initiative) 21 ♗b5 ♖d8 22 ♗xc6 ♖d2+ 23 ♔g3 bxc6 24 ♖hc1 ♗c2 25 ♘c3 a5 with equality; Bareev-Ehlvest, USSR 1986.

b2) 19 ♗b5! (a fine move that makes e2 available for the king) 19...♘b4?! (19...♗xe3) 20 ♔e2 ♘c2 21 ♖ac1 (21 ♘e4) 21...♘xe3 22 ♘e4 ♗d4 23 ♘xf6+ ♔h8?! (23...♔g7 24 ♘e8+ ♔f8 25 ♘d6 a6) 24 ♖c7 ⩲ Oud-Wealer, Corr 1989.

12 |

... |

♖d8+ |

13 |

♔c1 |

♘a6 |

13...♗xc5 14 e4 ♗h7 15 ♘a5 b6 16 ♘b3 ♗e3+ 17 ♔c2 ♘c6 18 ♖e1 is far from clear.

After 13...♘c6!? 14 e4 ♗h7, as in Akopian-Oll, New York Open 1994, Byrne and Mednis suggest 15 ♗e2.

14 |

e4 |

♘xc5 |

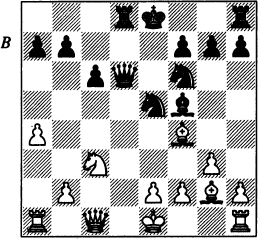

15 |

♔c2 (D) |

|

White would have serious development problems after 15 exf5 ♘b3+ 16 ♔b1 ♘xa1 17 ♔xa1 ♗xc3 18 bxc3 ♖d1+ 19 ♔b2 exf5.

15 |

... |

♗h7 |

16 |

♗e2 |

g5 |

Hertneck suggests 16...♖ac8 as a possible improvement, since if White plays by analogy 17 ♖hd1, then Black can exchange rooks and take on c3 and a4, without having to worry about ♗xc5. John Nunn suggests 17 a5!?, simply taking the pawn ‘off prise’. Then 17...♗xc3 18 bxc3 ♘fxe4 19 fxe4 ♗xe4+ 20 ♔b2 g5 21 ♗g3 ♗xg2 22 ♖hg1 ♗d5 23 ♘d6 may offer White some chances, since Black’s pawns are at least no better than the piece.

17 |

♗f2 |

♖ac8 |

The alternative is 17...♘d5 18 ♖hd1 (for 18 ♘a2 ♖ac8 19 ♖hd1 see the game) 18...♘f4 19 ♗f1 f5! 20 ♗xc5 ♗xc5 21 g3 ♘h5 22 ♔b3 ⩲ (Kamsky).

18 |

♖hd1 |

♘d5 |

19 |

♘a2 |

♗a5 |

19...a5 is much better, and leads to great complications, i.e. 20 ♘xb4 ♘xb4+ 21 ♔c3 ♖xd1 22 ♖xd1 ♘a2+ (22...♘xa4+ 23 ♔b3 ♘c5+ 24 ♗xc5 ♖xc5 25 ♘xa5) 23 ♔d4 (or 23 ♔d2!? ⩲ Nunn) 23...♘b3+ (23...♘c1 looks better, the point being that 24 ♗f1?? fails to 24...♖d8+, but 24 ♖e1 may still give White an edge) 24 ♔e5 ♔g7 25 ♖d7 and here Kamsky ends his analysis, assessing the position as unclear, although it looks very good for White, e.g. 25...♘ac1 26 ♗f1 ♘c5 27 ♗xc5 ♖xc5+ 28 ♔d6. Further analysis is definitely required if you want to go into such a line.

20 ♗xc5!

The white king needs a square; this exchange makes b3 available.

20 |

... |

♖xc5 |

21 |

♔b3 |

♘f4 |

22 |

♘xa5 |

♖xd1 |

23 |

♖xd1 |

♖xa5 |

24 |

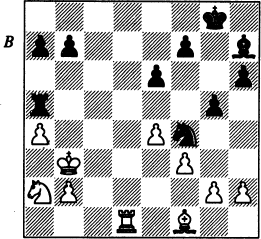

♗f1 (D) |

White’s strategy has turned out very well – Black’s bishop has been walled up on h7 and is completely out of play. Black’s only chance was now 24...g4! but accurate play still gives White a good position: 25 g3 ♘h5 26 f4!! ♗xe4 27 ♘c3 ♗c6 28 ♔b4 b6 29 ♘b5! a6 30 ♘c3 ♘f6 31 ♖d6 ♖c5 and now either 32 ♗xa6 or 32 a5!? leave White with an advantage.

Instead, the game concluded in one-sided fashion:

24...e5?! 25 ♘c3 ♘e6 26 ♘b5 a6 27 ♘d6 b5 28 axb5 axb5 29 ♘xb5

With an extra pawn and the black bishop still fighting to come out, Kamsky has no problems winning the game.

29...g4 30♗c4 gxf3 31 gxf3 ♘g5 32 ♖d3 ♗g6 33 h4 ♘h3 34 ♘d6 ♖a8 35 ♔b4 ♖b8+ 36 ♔c3 ♘g1 37 ♖e3 ♗h5 38 b4 ♔f8 39 b5 f6 40 ♔b4♘xf3 41 ♔c5 1-0