This chapter deals with a couple of sharp variations which fall somewhere between the Slav and the Semi-Slav; Black plays...e6 and ...c6, but delays...♘f6. This may be intended simply as a clever move order to reach the Semi-Slav while avoiding some unpleasant exchange variations, but Black may also choose to give the move-order independent significance after 4 ♘f3 by capturing on c4 (the Abrahams). Instead White may take the bull by the horns with the immediate central thrust 4 e4. These lines constitute our subject-matter here.

Marshall’s Gambit

Since Black has delayed developing his king’s knight (to prevent the pin with ♗g5), it is logical for White to exploit Black’s lack of control over e4 with Marshall’s sharp pawn sacrifice. If these positions are not to your taste, we can recommend 4 ♘f3, leading to the Abrahams/Noteboom (4...dxc4) or the Semi-Slav proper (4...♘f6).

Game 25

Lautier – M.Gurevich

Biel IZ 1993

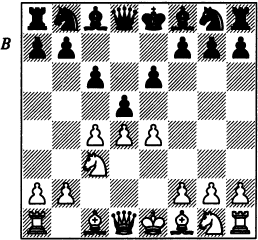

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 ♘c3

3 |

... |

c6 |

4 |

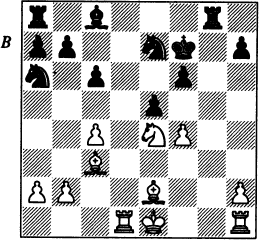

e4 (D) |

|

4 |

... |

dxe4 |

If Black doesn’t want to go into the complications following White’s pawn sacrifice, he could try 4...♗b4!?. This move is very rarely played but there doesn’t seem to be a simple way for White to gain a substantial advantage:

a) 5 exd5 cxd5 6 ♘f3 ♘f6 is the Caro-Kann, Panov Attack, and not dealt with in this book.

b) 5 e5 ♘e7 is possible. Then 6 a3 ♗xc3+ 7 bxc3 b6 8 cxd5?! (8 ♘f3) 8...♕xd5 9 ♘f3 c5 gave Black a good game in Borisenko-Korchnoi, Moscow 1955, but 6 ♘f3 looks better.

5 |

♘xe4 |

♗b4+ |

a) 5...♘f6 6 ♘xf6+ ♕xf6 7 ♘f3 h6 (7...♗b4+ 8 ♗d2 ♗xd2+ 9 ♕xd2 ⩲) 8 ♗d2 ♕d8 9 ♗c3 ♗e7 10 ♗d3 with better prospects for White; Reindermann-Hartmans, Purmerend 1993.

b) 5...♘d7 6 ♘f3 ♘gf6 7 ♗d3 ♘xe4 8 ♗xe4 ♗b4+ 9 ♗d2 ♕a5 10 0-0 ♗xd2 11 ♘xd2 0-0 12 ♕c2 ⩲ Vaiser-Dejkalo, Tallinn 1986.

6 |

♗d2 |

|

This move constitutes the gambit itself, though by this point White has little option if he wishes to make anything of the opening, since 6 ♘c3 c5 (or 6...e5!?) 7 ♘f3 ♘f6 8 ♗e2 ♘c6 promises White nothing.

6 |

... |

♕xd4 |

7 |

♗xb4 |

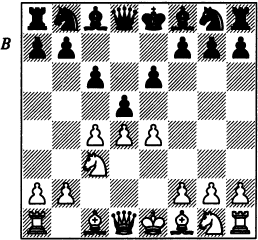

♕xe4+ (D) |

The key position. White’s compensation is based on his lead in development, his bishop pair and Black’s sensitive dark squares.

8 |

♗e2 |

|

White’s first major decision is between the text, which invites Black to grab another pawn on g2, and 8 ♘e2 which holds on to this pawn but delays White’s natural development. It is not obvious which of these moves is better; the main game certainly shows the advantages of the bishop move, but there are some unanswered questions, while the knight move may have been underestimated.

a) 8...♘d7 9 ♕d6 c5 (9...a5!? 10 ♗a3 ♕e5 {10...c5!? Stoica} 11 ♕d2 ♘gf6 was played in Hauchard-Dorfman, Brussels Z 1993, whereupon 12 f4 would have been far more testing than 12 0-0-0?! ♘e4) 10 ♗c3 ♘gf6 11 0-0-0 e5 (11...♕c6 12 ♕g3 ♖g8 13 f3 ♔e7 14 ♘f4 b6 15 ♘d3 ♗a6 16 ♘e5 ♘xe5 17 ♗xe5 ♖ad8 18 ♗e2 ♕a4 19 ♔b1 ♘d5 20 b3 ♕a5 21 ♗b2! ± G.Georgadze-Matlak, Naleczow 1989) 12 ♘g3 ♕c6 13 ♗xe5 ± G.Georgadze-Maliutin, USSR 1991.

b) 8...♘a6 9 ♗f8! (a striking move, characteristic of Marshall’s Gambit) 9...♘e7 (9...♕g6 10 ♕d2 ♕f6 11 ♗d6 ♘e7 12 0-0-0 0-0 13 ♘c3 ♖d8 14 ♗d3 ♘g615 ♘e4 ♕d4 16 ♕g5 with better prospects for White; Terpugov-Smyslov, Leningrad 1949) 10 ♗xg7 ♘b4 (10...♖g8 11 ♗f6 ♖g6 12 ♕d4 is better for White) 11 ♗xh8 e5 12 ♕d6 ♘c2+ 13 ♔d2 ♗f5 14 ♖d1! (14 ♘g3 ♕f4+ 15 ♔c3 ♘d5+! 16 cxd5 ♕d4+ 17 ♔b3 ♘xa1+ 18 ♔a3 ♘c2+ 19 ♔b3 ♘a1+ ½-½ Gomez Esteban-Illescas, Lisbon Z 1993) 14...♖d8 15 ♕xd8+ ♔xd8 16 ♔c1+ (16 ♘g3? ♕f4+ 17 ♔c3+ ♘d5+! 18 ♔b3 ♘d4+ 19 ♖xd4 ♕xd4 20 cxd5 ♗d3! –+ Berg-Hector, Århus 1993) 16...♔e8 17 ♘c3 ♕f4+ 18 ♖d2 (Illescas). The position is still highly unclear but White’s prospects should be preferred.

c) 8...♘e7 9 ♕d2! (Georgadze’s move) 9...c5 10 0-0-0 0-0 11 ♗xc5 ♘bc6 (11...♕xc4+ 12 ♕c3 ♕xc3+ 13 ♘xc3 ♘bc6 14 ♗b5 +−) 12 ♘d4 ♘xd4 13 ♗xe7 e5 14 ♗xf8 ♔xf8 15 f3 ♕c6 16 ♗d3 + G.Georgadze-Cruz Lopez, San Sebastian 1991.

8 |

... |

♘a6 |

Black has various other moves:

a) 8...♕xg2 9 ♕d6 ♘d7 (9...c5 10 ♖d1! +– Wells) 10 0-0-0 ♕xf2 (10...♕g5+ 11 f4 ♕e7 12♕d2c5 13 ♗c3 ♘gf6 14 ♗f3 0-0 15 ♕g2 ♖b8 16 ♘e2 followed by a kingside attack gave White the better chances in Furman-Kopaev, USSR 1949) 11 ♗h5 ♕e3+ 12 ♔b1 ♕e5 13 ♗xf7+ ♔xf7 14 ♖f1+ ♘gf6 15 ♕e7+ ♔g8 and now 16 ♘f3! wins, despite White being a piece and two pawns down, e.g. 16...♕f5+ 17 ♔a1 ♕g6 18 ♖hg1 ♕f7 19 ♖xg7+! ♕xg7 (or 19...♔xg7 20 ♖g1+) 20 ♕xe6+ ♕f7 21 ♖g1 + mating.

b) 8...c5:

b1) 9 ♗c3 ♘e7 10 ♘f3 (an attempt to revive a line considered dubious; its one recent outing was a resounding success) 10...0-0 11 0-0 f6 12 ♗d3 ♕f4 13 ♖e1 ♘bc6 14 ♘d2 ♖d8 15 ♘e4 f5 16 g3 ♕c7 (16...♖xd3? 17 ♕h5 +−; 16...♕xe4! is more testing) 17 ♘g5 e5 18 ♕h5 h6 19 ♕f7+ ♔h8 20 ♘f3 (20 h4) 20...♘d5 21 ♘g5 ♘de7 (offering a repetition; 21...hxg5 22 ♕h5+ ♔g8 23 cxd5 ♘d4) 22 h4! hxg5 23 hxg5 ♗e6 (23...f4 24 ♔g2 f3+ 25 ♕xf3 is good for White, since 25...♗h3+ 26 ♔xh3 ♕d7+ 27 ♔g2 ♕xd3 is met by 28 ♕f7 +−) 24 ♕xe6 ♘d4 25 ♗xd4 ♖xd4 26 ♗xf5 +– I.Sokolov-San Segundo, Madrid 1994.

b2) 9♗xc5 ♕xg2 and now:

b21) 10 ♕d4 ♘d7 (10...♘c6 11 ♕d6 ♘ge7 12 0-0-0 is good for White; 10...♕xh1? fails to 11 ♕xg7 ♘d7 12 ♗d6) 11 0-0-0! ♕g5+ 12 f4 ♕f6 13 ♘f3 ♕xd4 (13...♘xc5 14 ♕xc5 ♕xf4+ 15 ♘d2 ♘f6 16 ♖hg1 ♘d7 17 ♕a3 ♕e5 18 ♗f3 ♘c5 19 ♖xg7! ± Yuferov-Moroz, Mikolaiki 1991) 14 ♗xd4 f6 15 ♖hg1 ♔f7 16 ♘d2 ♘e7 17 ♘e4 ♘f5 18 ♗c3 was good for White in Vera-Semkov, Rome 1990.

b22) 10 ♗f3 ♕g5 11 ♗d6 ♘e7 12 ♘e2:

b221) 12...♘bc6 13 ♖g1 ♕f6 14 ♘c3 ♘f5 (14...♘d4! 15 ♗e4 ♘df5 16 ♗a3 gives White compensation – Spraggett) 15 ♗xc6+ bxc6 16 ♘e4 ♕d8 17 ♕d2 and with the black king stuck in the centre White enjoys a clear advantage; Spraggett-Majorovas, Cannes 1992.

b222) 12...♘f5 13 ♗a3 ♘c6 14 ♗xc6+ bxc6 15 ♖g1 ♕d8 16 ♕xd8+ ♔xd8 17 0-0-0+ ♔c7 18 ♘g3 ±.

c) 8...♘d7 9 ♕d6 (9 ♘f3 c5 {9...b6!?} 10 ♗c3 ♘e7 11 0-0!? Crouch-Wells, Dublin Z 1993) 9...c5 (for 9...♕xg2 10 0-0-0, see line ‘a’) 10 ♗c3!? (after 10 ♗xc5 ♕xg2 11 ♗f3 ♕g5 12 ♗e3 ♕a5+ 13 b4 ♕e5 14 ♕xe5 ♘xe5 15 ♗e2 the pair of bishops gives White some compensation for the sacrificed pawn) 10...♘e7 11 ♕d2 0-0 12 0-0-0 ♘g6 13 ♘h3!? ♕xg2 14 ♕e3 e5 15 ♖hg1 ♕c6 16 f4! exf4 17 ♘xf4 ♘f6 18 ♗f3 ♕a6 19 ♘d5 ♘xd5 20 ♗xd5 ♗d7 21 h4 ♖ae8 22 ♕xc5. White has a clear advantage but A.Sokolov-Bagirov, Riga 1993 now came to a very sudden end after 22...♕xa2? 23 ♖xg6! 1-0. 23...hxg6 is answered with 24 ♕d4.

d) 8...♘e7 9 ♕d2 (9 ♘f3 ♘d5! 10 ♗a3 ♘f4 11 0-0 ♘xe2+ 12 ♔h1 « Borisenko-Kalikstein, Uzbekistan Ch 1992) 9...♘g6 10 ♘h3!? (10 0-0-0 ♕f4) 10...c5 11 0-0-0 (11 ♘g5 ♕f4 {11...♕d4!} 12 ♗xc5 ♕xd2+ 13 ♔xd2 ±) 11...♘d7 12 ♘g5 ♕f4 13 ♗c3 ♕xd2+ 14 ♖xd2 0-0 15 ♖hd1 with a good game for White.

9 |

♗c3 |

|

9 ♗d6 b6 (9...e5 10 ♕b3 ♘f6 11 ♕g3! ± Yudovich) 10 ♘f3 ♗b7 11 0-0 0-0-0 (11...♖d8 I.Sokolov) 12 ♘e5 ♕f5 13 ♗g4 ♕f6 14 ♗f3 ♘e7 15 ♗xe7 ♕xe7 16 ♕a4 ♕c7 17 ♘xc6 ♗xc6 18 ♕xa6+ ♔b8 = Verduga-Vera, Havana 1986.

9 |

... |

♘e7 |

Black has some alternatives here but they all seem to give White an edge:

a) 9...♘f6 10 ♘f3 ♗d7 11 0-0 0-0-0 12 ♗d3 ♕g4 13 ♕c2 ♕f4 14 b4 c5 15 b5 ♘b4 16 ♗xb4 cxb4 17 ♖fe1 ± I.Sokolov-Akopian, Groningen 1991.

b) 9...e5 10 ♕d6 ♘e7 11 ♖d1 ♗e6 12 ♘f3 ♘f5 13 ♕xe5 ♕xe5 14 ♗xe5 f6 15 ♗c3 c5 16 g4 ♘e7 17 g5 ♔f7 18 gxf6 gxf6 19 ♘h4 ⩲ Semkov-Spassov, Sofia 1991.

c) 9...f6 10 ♕d6 ♗d7 11 0-0-0 0-0-0 12 ♕g3 ♕g6 13 ♕e3 b6 14 ♘h3 ♕h6 15 f4 ♘e7 16 g4 e5 17 ♗d2 ♘c5 18 ♕a3 e4 19 ♘f2 ⩲ Bronstein-Szily, Budapest 1949.

10 |

♗xg7! |

|

10 ♘f3 0-0 11 0-0 ♘g6 12 ♖e1 ♕f4 (12...f6!?) 13 b4 f6 14 ♖c1 ♕c7 15 b5 ♘b8 16 ♕b3 ♘f4 17 ♗f1 e5 18 ♗d2 ♘e6 19 ♕b1 with some compensation; Antonsen-Votruba, Tåstrup 1992.

10 |

... |

♖g8 |

11 |

♗f6! |

|

This is far better than 11 ♗c3?, although Black must play precisely to highlight the shortcomings of this move: 11...♘d5!! 12cxd5 ♕xg2 13 dxe6 (the careless 13 ♗f3? runs into 13...♕xg1+!) 13...♗xe6 14 ♗f6 ♖g6! 15♗h4 ♕xh1 16 ♕d6 ♖g5!! (Razmoglin) and Black refutes the attack.

11 |

... |

♕f4 |

11...♖g6 12 ♗c3 (12 ♗xe7 ♔xe7 13 ♕d2 e5 14 ♖d1 ♗e6 15 f3 ♕d4 16 ♕xd4 exd4 17 ♔f2 ♖d8 = Vaiser-Savchenko, Moscow Tal mem 1992) 12...♘d5 13 cxd5 ♕xg2 14 ♕d4! ±.

12 |

♗c3! |

|

Keeping the dark-squared bishop certainly makes sense, but 12 ♗xe7 is also possible: 12...♔xe7 13 g3 ♕e5 (Wells later preferred 13...♕f6) 14 ♕b1! ⩲ ♗d7 15 ♘f3 ♕a5+ 16 ♔f1 ♕h5 17 ♕d3 ♖ad8 18 ♖d1 ♗c8 19 ♕e3 ♕h3+ 20 ♔e1 ♖xd1+ 21 ♔xd1 ♖d8+ 22 ♗d3 ♕f5 23 ♔e2 ♕g4 24 ♖c1 and White, with the better pawn formation, keeps a small edge; Flear-Wells, London Lloyds Bank 1993.

12 |

... |

♖xg2 |

13 |

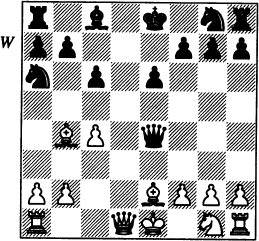

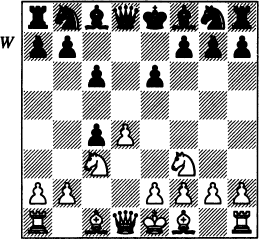

♘13 (D) |

|

This seems to be the critical position.

13 |

... |

f6 |

After the game the players analysed a number of other moves for Black:

a) 13...♘c5 14 ♗e5 ♕h6 15 ♕d4 b6 16 ♖d1 ♗b7 17 ♗f6! with the idea of b4 +–.

b) 13...♘f5 14 ♗e5 ♕h6 15 ♕d2! ♖g8 (15...♕xd2+ 16 ♘xd2 threatens 17 ♗g3 and 16...♖g6 17 ♘e4 is also better for White) 16 ♗f4 ♕f8 17 0-0-0 ♕e7 18 ♖hg1 +−.

c) 13...♗d7 14 ♗e5 ♕h6 15 ♗g3 ♘f5 16 ♕d2! +–.

These three examples show how important the move ♗e5 is, so this leaves us with only:

d) 13...♘g6 leaves the rook in trouble on g2 after 14 ♔f1!:

d1) 14...e5 (a tactical method which wins the queen but gives up too many pieces) 15 ♔xg2 ♗h3+ 16 ♔xh3 ♕f5+ 17 ♔g2 ♘f4+ 18 ♔f1 ♕h3+ 19 ♔e1 ♘g2+ 20 ♔d2 ♖d8+ 21 ♔c2 ♖xd1 22 ♖axd1 +−.

d2) 14...♘h4 15 ♗e5 (this manoeuvre again!) 15...♕f5 16 ♗g3 ♕h3 17 ♔e1! and the rook is trapped (but 17 ♘g5? would be very careless because of 17...♖g1++! 18 ♔xg1 ♕g2#!)

d3) 14...♖g4 15 h3 +−.

14 |

♕d2! |

|

An extremely powerful move. 14 ♕d3 is another possibility, but by exchanging queens White robs Black of his most important defensive piece.

14 |

... |

♕xd2+ |

15 |

♘xd2 |

e5 |

16 |

♘e4 |

♔f7 |

17 |

♖dl |

|

There’s no point winning an exchange with 17 ♘g3 since Black obtains significant counterplay after 17...♘g6 18 ♗f3 ♘h4 19 ♗xg2 ♘xg2+ 20 ♔e2 ♘f4+. White should not cash in his compensation so cheaply.

17 |

... |

♖g8?! |

This plausible move is probably a mistake, since after White’s next move Black is pretty much lost. In view of this Black should have tried 17...♘c7 but after 18 ♗h5+ White wins the exchange under more favourable circumstances than on move 17, e.g. 18...♘g6 19 ♗f3 ♘h4 20 ♗xg2 ♘xg2+ 21 ♔e2 ♘f4+ 22 ♔f3±.

18 |

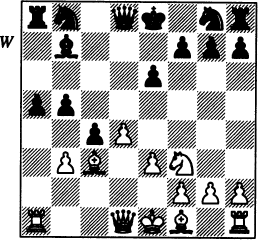

f4! (D) |

|

18 |

... |

♘g6 |

19 |

♖d6 |

♔e7 |

19...♗e6 runs into 20 f5!.

20 |

♖xf6 |

♘xf4 |

20...exf4 is well answered by 21 h4!.

21 |

♗xe5 |

♘xe2 |

22 |

♗d6+ |

♔e8 |

23 |

♔xe2 |

♗h3 |

Black could gain a tempo with 23...♗g4+ but that would give some problems on the g-file, e.g. 24 ♔e3 ♖d8 25 ♖g1.

24 |

♖h6 |

♗g4+ |

24...♗g2 25 ♖g1 ♗f3+ doesn’t help since 26 ♔xf3 ♖xg1 27 ♖xh7 is decisive.

25 |

♔e3 |

♗f5 |

26 |

♘f6+ |

♔f7 |

27 |

♘xg8 |

♖xg8 |

28 |

♔f4! |

|

With an extra exchange White had no difficulties in winning the game: 28...♗g6 29 ♖e1 ♖d8 30 ♖e7+ ♔f6 31 c5 ♘b4 32 ♖exh7 ♘d5+ 33 ♔f3 ♖e8 34 h4 ♖e3+ 35 ♔f2 ♔f5 36 ♖g7 ♖e6 37 h5 1-0.

Abrahams/Noteboom Variation

This variation, developed first by Gerald Abrahams in Britain, and later by Noteboom in the Netherlands, is one of the more violent lines in the Queen’s Gambit. On move four Black grabs a ‘hot’ pawn, and imparts a great deal of imbalance into the position.

White can certainly win his pawn back, and gain a central preponderance, but Black’s queenside pawns and active pieces keep matters double-edged.

In this section we shall discuss some of the more interesting deviations from the main line, and some gambit approaches for White in the early stages.

Game 26

Aseev – Tregubov

Sochi 1993

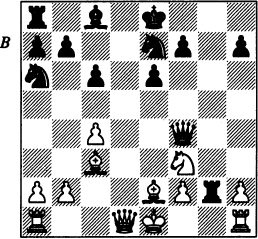

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 ♘c3 c6

4 |

♘f3 |

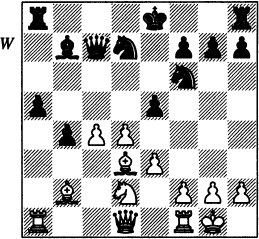

dxc4 (D) |

5 |

a4 |

|

Those who are desperate for a sharp and messy position may wish to investigate 5 e4 b5 6 ♗g5. Then 6...♘f6 is the Botvinnik Variation of the Semi-Slav (when 7 a4 stays inside the scope of this book), whilst 6...f6 leads into uncharted territory, in which Black’s pawn weaknesses and White’s central preponderance ought to provide compensation. Gaprindashvili-Bagirov, Ter Apel 1990 saw instead 6...♕b6 7 a4 ♘d7 8 ♗e2 ♘gf6 9 axb5 cxb5 10 d5! ♗b4 (10...exd5 11 exd5) 11 ♗e3 ♘c5 12 0-0 0-0 13 ♘a2 ♗a5 14 ♘d4! ♘cxe4 (Ftačnik analysed 14...exd5 15 b4 cxb3 16 ♘xb3 ♘fxe4 17 ♘xc5 ♘xc5 18 ♕c2 +− and 14...♘fxe4 15 b4 cxb3 16 ♘xb3 ♕c7 17 ♘xc5 ♘xc5 18 ♖c1 ♗b6 19 d6 +−) 15 ♘xe6 ♕d6 16 ♘xf8 ♗c7 17 g3 ♕xf8 18 ♗f3 ♗h3 19 ♖e1 a5 (19...♖d8 20 ♗xe4 ♘xe4 21 ♗xa7 ±) 20 ♗d4 ♘c5 21 ♘c3 ♘d3 (21...♖b8!?) 22 ♘xb5! ♘xe1 23 ♕xe1 ♖e8 24 ♕c3 ♗d8 25 ♕xc4 +–.

A further approach with which White makes no immediate attempt to regain the pawn is the Catalanstyle 5 g3. This has scored well in practice:

a) 5...b5 6 ♗g2 ♗b7 7 0-0 ♘d7:

a1) 8 e4 ♘gf6 9 e5 ♘d5 10 ♘g5 ♗e7 11 ♕h5 g6 12 ♕h6 ♗f8 13 ♕h3 ♗e7 14 ♘ce4 ♕c7 15 ♖e1 ♕b6 16 ♘d6+ ♗xd6 17 exd6 left Black defenceless in Sunye Neto-Petursson, Manila IZ 1990.

a2) 8 ♖b1?! ♘gf6 9 b3 cxb3 10 ♕xb3 ♗e7 11 ♘e5 ♘d5 12 ♘xb5 cxb5 13 ♕xb5 and now 13...♗c8? 14 ♕c6 +– Rausis-S.Nikolov, Sofia 1989 is no good, but I’m not sure what White’s doing after 13...♖b8, e.g. 14 ♗xd5 ♗c8 15 ♕c6 ♖xb1 16 ♘xf7 ♖b6! and White can obtain a whole load of pawns for a rook, but that is all.

b) 5...♘f6 6 ♗g2 ♘bd7 7 0-0:

b1) 7...♗d6 8 ♕c2 0-0 9 ♖d1 ♕e7 10 ♗g5 h6 11 ♗xf6 ♘xf6 12 ♘d2 e5 13 d5 cxd5 14 ♘xd5 ♘xd5 15 ♗xd5 ⩲ c3 16 ♕xc3 ♗g4?! 17 ♘c4 ♖ac8 18 ♕e3 ♗b8 19 ♕e4 ♕g5 20 h4 ± Lputian-Arencibia, Biel IZ 1993.

b2) 7...♕a5 8 e4 e5 9 dxe5 ♘g4 10 ♗f4 ♘gxe5 11 ♘xe5 ♘xe5 12 ♘d5! ± Ligterink-Kuijf, Budel Z 1987.

5 |

... |

♗b4 |

6 |

e3 |

b5 |

7 |

♗d2 |

|

The continuation 7 ♘d2 ♕b6 8 ♕g4 ♔f8 9 g3 ♘f6 10 ♕f3 ♗b7 11 ♗g2 a6 12 0-0 ♘bd7 got a bad reputation following the game Speelman-Flear, London 1986, in which 13 ♘a2 ♗d6 14 b3 cxb3 15 ♘xb3 ♔e7 failed to give White sufficient compensation. However, Beliavsky-Kharlov, USSR Cht (Azov) 1991 saw White find a more effective way to pursue the initiative: 13 axb5 axb5 14 ♖xa8+ ♗xa8 15 ♘de4 ♔e7 16 ♘xf6 ♘xf6 17 e4 c5 18 d5 ♖e8 (18...♗xc3) 19 ♗g5 e5 20 ♗xf6+ gxf6 21 ♘d1♗d2 22 ♕e2 ♕a5 23 f4 with good compensation.

7 |

... |

a5 |

This is Black’s best reply. After other moves Black has problems meeting White’s idea of shattering his queenside pawns with b3:

a) 7...♘f6 8 axb5 ♗xc3 9 ♗xc3 cxb5 10 b3 0-0 11 bxc4 bxc4 12 ♗xc4 ⩲ Bagirov-Kupreichik, Lvov 1984.

b) 7...♗b7 8 b3 ♘f6 (8...a5 can be met by 9 bxc4 bxc4 10 ♗xc4 ⩲ Spraggett-Klinger, Vienna 1986 or 9 axb5, transposing to the main game) 9 axb5 ♗xc3 10 ♗xc3 cxb5 11 bxc4 bxc4 12 ♗xc4 ♕c7 13 ♗b5+ ♗c6 14 ♗a5 ♕d6 15 ♕b3 ♗xb5 16 ♕xb5+ ♕c6 17 ♕b4 ♕d5 18 ♘e5! ♕xg2 19 ♔e2 ♘bd7 20 ♖hg1 ♕e4 21 ♕a4 ♖c8 22 ♖ac1 +− Lautier-Ruban, Sochi 1989.

c) 7...♕e7 8 ♕c2 ♘f6 9 axb5 ♗xc3 10 ♕xc3 cxb5 11 b3 ♘e4 12 ♕a5 ♘xd2 13 ♘xd2 ± Denker-Kristoffel, Groningen 1946.

d) 7...♕b6 is best met by 8 ♘e5!.

8 |

axb5 |

|

8 ♕b1!? ♗d7 (8...♕b6!? should be considered) 9 ♗e2 ♖a6?! (Ftačnik prefers 9...♘f6 10 0-0 0-0) 10 0-0 ♘f6 11 e4 ♗e7 12 ♖d1 ♕c8 (12...b4 13 ♘a2 ±) 13 ♗g5 h6 14 ♗h4 ♗b4 15 d5! ± Uhlmann-Serrer, German Ch 1991.

8 |

... |

♗xc3 |

9 |

♗xc3 |

|

9 bxc3 cxb5 10 ♕b1 ♗a6 11 ♗e2 ♘c6 12 0-0 ♘f6 13 e4 h6 14 ♗d1!? gave White compensation for the pawn in M.Gurevich-Bjork, Saltsjöbaden Rilton Cup 1987.

9 |

... |

cxb5 |

10 |

b3 |

♗b7 (D) |

11 |

bxc4 |

|

White should not be tempted into 11 d5 ♘f6 12 bxc4 b4 13 ♗xf6 ♕xf6 14 ♕a4+ ♘d7 15 ♘d4 e5 16 ♘b3 ♔e7! with a position which is at the very least fine for Black, e.g. 17 ♗e2 ♕d6! Rogers-Krasenkov, Hastings 1993/4.

11 |

... |

b4 |

12 |

♗b2 |

♘f6 |

13 |

♗d3 |

♘bd7 |

14 |

0-0 |

♕c7 |

14...♖a7?! 15 ♖e1 ♕a8 16 e4! a4?! 17 d5 ♘c5 18 ♗d4 ♘fd7 19 ♘e5! was pretty much decisive in Kir.Georgiev-Antunes, Manila OL 1992.

15 |

♘d2!? |

|

The normal line 15 ♕c2 0-0 16 e4 e5 17 ♖fe1 ♖fe8 18 c5 exd4 19 ♗xd4 looks fine for Black after Kramnik’s useful move 19...h6!, but White may well wish to investigate 15 ♖el 0-0 (15...e5! Van der Tak) 16 c5 ♗e4 (16...♘e4 17 ♕c2 f5 18 ♘d2 ♘xd2 19 ♕xd2 ♘f6 20 f3 ♗d5 21 ♗b5 ± Brigden-Amoviel, Corr 1988) 17 ♗b5 ♖fb8 18 ♗a4 ♖d8 19 ♘d2 ♗c6 20 ♕e2 ♗xa4 21 ♖xa4 e5 22 ♘b3 ± Malaniuk-M.Raičević, Kecskemet 1989.

15 |

... |

e5! (D) |

Black should avoid 15...0-0? 16 f4! a4 17 ♖c1 ♖fd8 18 ♕e2 ♘f8 19 e4 b3 20 ♘b1 ♕b6 (Vilela-Ruban, Santa Clara 1991) 21 e5 ±.

16 |

♖e1 |

|

Aseev suggests 16 f3!?.

16 |

... |

0-0 |

17 |

♘f1!? |

♖fd8 |

Aseev points out that 17...a4 fails to 18 dxe5 ♘xe5 19 ♗xe5 ♕xe5 20 ♖xa4 ±.

17...♖fe8 should also be met by 18 f3.

18 |

f3 |

|

Glatman suggested 18 ♘g3, intending 18...e4 19 ♗e2 ♘e5 20 ♕c2 ⩲, but presumably he was forgetting that Black’s last move has made 18...a4 a viable option.

18 |

... |

♗c6? |

After this Black is in real trouble. Aseev mentions the line 18...e4 19 ♗e2 ♘e5 20 ♘d2 exf3 21 gxf3 ±, and suggests that Black should investigate 18...♘b6!?.

19 |

d5 |

♗b7 |

Even worse are 19...a4? 20 f4 a3 21 dxc6 ♘c5 22 ♗xe5 +− and 19...♘c5 20f4 +–.

20 |

♘g3 |

♘e8 |

21 |

f4! |

h6 |

21...g6 22 ♕f3 ±.

22 |

♘f5 |

♘ef6 |

23 |

♕f3 |

e4 |

23...♔f8 24 ♕g3 ♘e8 25 fxe5 +–.

24 |

♕g3 |

♘h5 |

24...g6 25 ♘xh6+ ♔g7 26 ♘f5+ ♔f8 27 d6! ♕c6 28 ♕h4 gxf5 29 ♕h8+ is winning for White (Glatman).

25 |

♕g4 |

exd3 |

26 |

♗xg7 |

1-0 |