One day I will find the right words, and they will be simple.

—JACK KEROUAC, THE DHARMA BUMS

If you have ever read a Dr. Seuss book, you may be familiar with words like fizza-ma-wizza-ma-dill, fiffer-feffer-feff, and truffula.

You may also be familiar with these: a, will, the.

Besides made-up words and rhymes, Dr. Seuss’s biggest trademark is the simplicity of his writing. Even compared to other children’s authors, Dr. Seuss pushed the limits. We can partly thank his Houghton Mifflin editor, William Spaulding, who after a string of successes presented Seuss with a list of just a few hundred simple words in the mid-1950s. Seuss had already published Horton Hears a Who!, And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street, and If I Ran the Zoo. But, as detailed in the New Yorker article “Cat People,” Spaulding wanted Seuss to go after an even younger audience: “Write me a story that first graders can’t put down!”

Seuss would later describe how he struggled with Spaulding’s challenge:

He sent me a list of about three hundred words and told me to make a book out of them. At first I thought it was impossible and ridiculous, and I was about to get out of the whole thing; then decided to look at the list one more time and to use the first two words that rhymed as the title of the book—cat and hat were the ones my eyes lighted on. I worked on the book for nine months—throwing it across the room and letting it hang for a while—but I finally got it done.

The result was The Cat in the Hat. It clocks in at 220 unique words, and to this day ranks as the second-most-selling book of Seuss’s career. The one book ahead of it? It’s Green Eggs and Ham, which uses just fifty words. All but one, anywhere, are one syllable.

Seuss’s two most popular books are those in which he restricted himself the most: Simplicity brought success.

Of course, Seuss was not writing for a general audience—he was writing for children still learning to read. It would be impossible to write a book with just fifty words if it weren’t covered in giant illustrations. And adult readers are looking for more than your average first-grader.

But what if there’s more to this idea? Sure, the books we read and love as adults are more complex—but just how complex? Is there an ideal level if you’re aiming to write the next number one bestseller? And where do the literary greats clock in?

The word lists that Dr. Seuss used when writing The Cat and the Hat and Green Eggs and Ham were created by a man named Rudolf Flesch. In his 1955 book Why Johnny Can’t Read, Flesch argued that reading education in America was in dire need of reform; he introduced the nation to phonics and his word lists ended up inspiring just the kind of revolution he was hoping for.

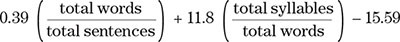

Flesch then went on to create a mathematical formula—the Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level test—that was capable of measuring the simplicity or complexity of any text. The formula itself is simple—just a couple of fractions weighted and then added together.

The score, by Flesch’s description, is the grade level required to understand the text. If a book is given a grade of 3, that means a third grader (and anyone older) could be expected to understand it.

The test works best when applied to large texts but it’s easy to understand with short samples. Take the first sentence in George Washington’s first State of the Union Address:

I embrace with great satisfaction the opportunity which now presents itself of congratulating you on the present favorable prospects of our public affairs.

At 43 syllables and 23 words, the sentence would be given a grade-level score of 15.

Compare to the first sentence in George W. Bush’s last State of the Union Address:

Seven years have passed since I first stood before you at this rostrum.

It has 16 syllables, 13 words, and a grade-level score of 4.

The numbers 4 and 15 may seem arbitrary, but side by side it’s easy to see why the first sentence is given the higher complexity score. The grade scores tend to average out over the course of a longer text, but short samples like these do show the limits of a metric like Flesch-Kincaid. It has its detractors, who criticize the formula for being too simple or not capturing context or fumbling the exact grade levels.

For instance, there are some unusual writers whose unique style breaks the simple scoring system. Green Eggs and Ham has a negative grade-level score, -1.3 to be exact. Consider the passage below:

Not in a box.

Not with a fox.

Not in a house.

Not with a mouse.

I would not eat them here or there.

It has 24 words and 24 syllables spread out over 5 sentences, which yields a negative score.

On the other end of the spectrum is William Faulkner. In The Sound and the Fury he disregards punctuation, which leaves him with a “sentence” composed of over 1,400 words. It has a Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level score of 551.

But these are the outliers, the texts that pose the biggest challenge. As a relative measure, Flesch-Kincaid works well, averaging out the irregular sentences over the length of a full book. Even The Sound and the Fury as a whole has a grade-level score of 20. Most books meant for a general audience, not by Faulkner and not by Seuss, will fall within the fourth to eleventh grade. Every New York Times number one bestseller since 1960 falls in this seven-grade-level spread.I Ultimately, Flesch-Kincaid’s simplicity is an advantage, allowing us to compare huge swathes of text across genres or generations.

If you follow U.S. politics you might see the Flesch-Kincaid formula pop up once a year when it’s time for the State of the Union. It has become a popular pastime to evaluate the complexity of these speeches, for doing so reveals an undeniable trend. When comparing all of the State of the Union addresses from America’s founding to the present, the Flesch-Kincaid test shows a steady decline in the sophistication of our political speech.

If you’re being optimistic, politics is reaching a wider audience. If you’re being cynical, politics is getting stupider by the decade.

In an article in the Guardian, titled perfectly “The state of our union is . . . dumber,” the authors used Flesch-Kincaid to determine that the annual presidential State of the Union Address has gone from an eighteenth-grade level pre-1900, to a twelfth grade level in the 1900s, and it’s now sunk below a tenth-grade level in the 2000s.

The role of the State of the Union has changed over the years. After all, when Washington was addressing Congress in 1790 it was meant as an actual addressII to Congress. The event has transformed into a national radio and television spectacle, making it important to reach every corner of America, regardless of age and education.

* * *

It might be one thing for the State of the Union to drift downward, but what about the world of books? Do we see any patterns when we look at the state of the American novel over time? Is the state of our fiction . . . dumber?

To find out, I collected every digitized number one New York Times bestseller since 1960III and ran the Flesch-Kincaid test on all 563 of them.IV

The overall trend, in just the last fifty-plus years, shows the same downward slope. The bestseller list is full of much simpler fiction. If you pick books by checking out what is trending on the list, chances are you are going to be picking up books of less sophistication today than you would forty or fifty years ago.

The black bar represents the reading level of the median book in each decade. The shaded region represents the middle 50 % of all books. In the 1960s the median book had a grade level of 8.0, with the middle half of all books coming in between 7.2 to 9.3. While 7.2 could be considered low fifty years ago, in 2014 there were 37 bestsellers, and 36 had a grade level of 7.2 or below. The floor for simplicity has become the ceiling. The number one bestseller with the highest reading level in 2014 was Daniel Silva’s The Heist, which had a score of 8.0. Out of all 37 books it was the one book that had a score that half a century ago would have been typical.

On the upper end, James Michener’s 1988 novel Alaska had a grade-level score of 11.1, making it the number one bestseller since 1960 with the highest reading level. Twenty-five books since 1960 have had a grade level of 9 or higher. But just two of these were written after 2000.

On the lower end, eight books tie for the lowest score of 4.4. All eight of these books were written after 2000, all by one of three high-volume writers: James Patterson, Janet Evanovich, and Nora Roberts.

These ultrapopular bestsellers with low reading levels are a recent phenomenon. Twenty-eight of the number one bestsellers since 1960 that I collected had a grade-level score below 5. Just two of these were written before 2000.

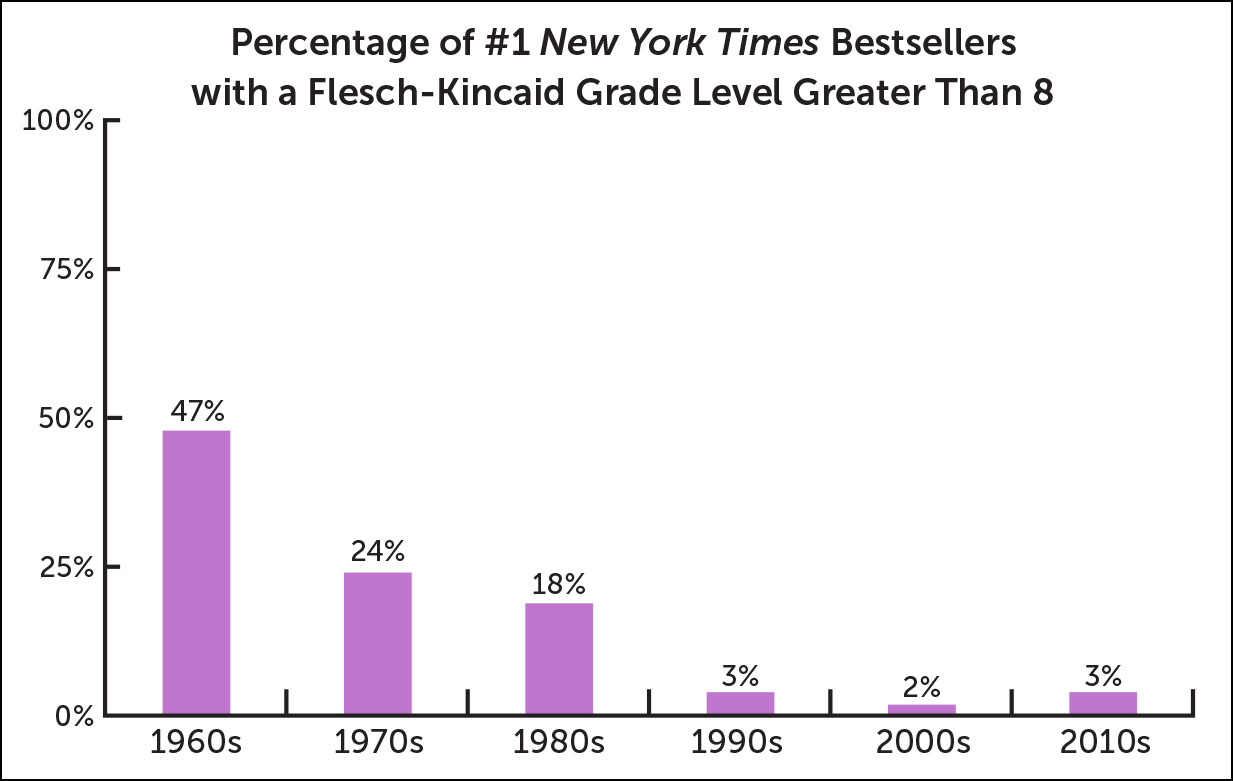

To see the trend before your eyes, below is a graph showing the percentage of books with a grade level greater than eight, the median score in the 1960s.

And on the next page is a graph showing the percentage of books with a grade level less than six. This is the median today.

The New York Times bestseller list holds a rarefied place in the book world. To have written a New York Times bestseller is to have made it. And for the general public, the list often serves as the public face of fiction, a guide to what’s worth reading. Yet in the last fifty years, there is no way around it: The books that we’re reading have become simpler and simpler.

There are two reasons this could be happening. The first would be that all popular books today are filled with simpler sentences and more monosyllabic words. The alternative is that the New York Times bestseller list is getting “dumber”—as the Guardian would put it—because more books of a “dumb” genre are reaching the top. I’ll call this the “guilty pleasure” theory. If quick reads like thrillers and romance novels now make the list more often than they did thirty years ago, the median reading level would move down even if each genre’s grade level stayed the same.

I’ve checked both theories, and the answer, it turns out, is: both.

There have always been “guilty pleasure” books on the list. In the 1960s it was Valley of the Dolls, in the 1970s, The Exorcist, in the 1980s, the books of the Bourne Trilogy, and in the 1990s The Lost World of the Jurassic Park series.

But without a doubt, there are more guilty pleasures on the list today than there used to be. In the 1960s a book would hold its top position on the list for many months at a time. Today, books jump up and down the chart much more rapidly. James Michener’s Hawaii and Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent were the only two books to reach number one bestseller status in 1960. In 2014 there were 37 that did, and the longest any one book claimed the top spot was four weeks (Grisham’s Gray Mountain). Prize-winning literary novels like The Corrections and The Goldfinch make the number one spot on occasion, but today it’s much more often dominated by commercial novels. This makes the contribution of the literary books less important to the median.

Looking at prizewinners rather than bestseller lists, we find that literary books haven’t declined in reading level nearly as much. That being said, they are not as complicated in terms of sentence length and word length as you might think. Complicated themes don’t always translate to complicated writing. The average for Pulitzer Prize winners in the 1960s was a 7.6 grade-level score, and in the 2000s a 7.1. In the years in between, the average was 7.4. There are many more outliers among the Pulitzer winners (Chabon’s The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay scored a 10.0 while Alice Walker’s The Color Purple, from the perspective of fourteen-year-old Celie, scores a 4.4), but there has not been a systematic shift over the years.

The growing presence of guilty pleasures is not the sole reason for the decline in bestseller reading levels, however. If we break down bestsellers by genre, we find that there has been a long-term shift within those guilty pleasures. Thrillers have become “dumber.” Romance has become “dumber.” There has been an across-the-board “dumbification” of popular fiction.

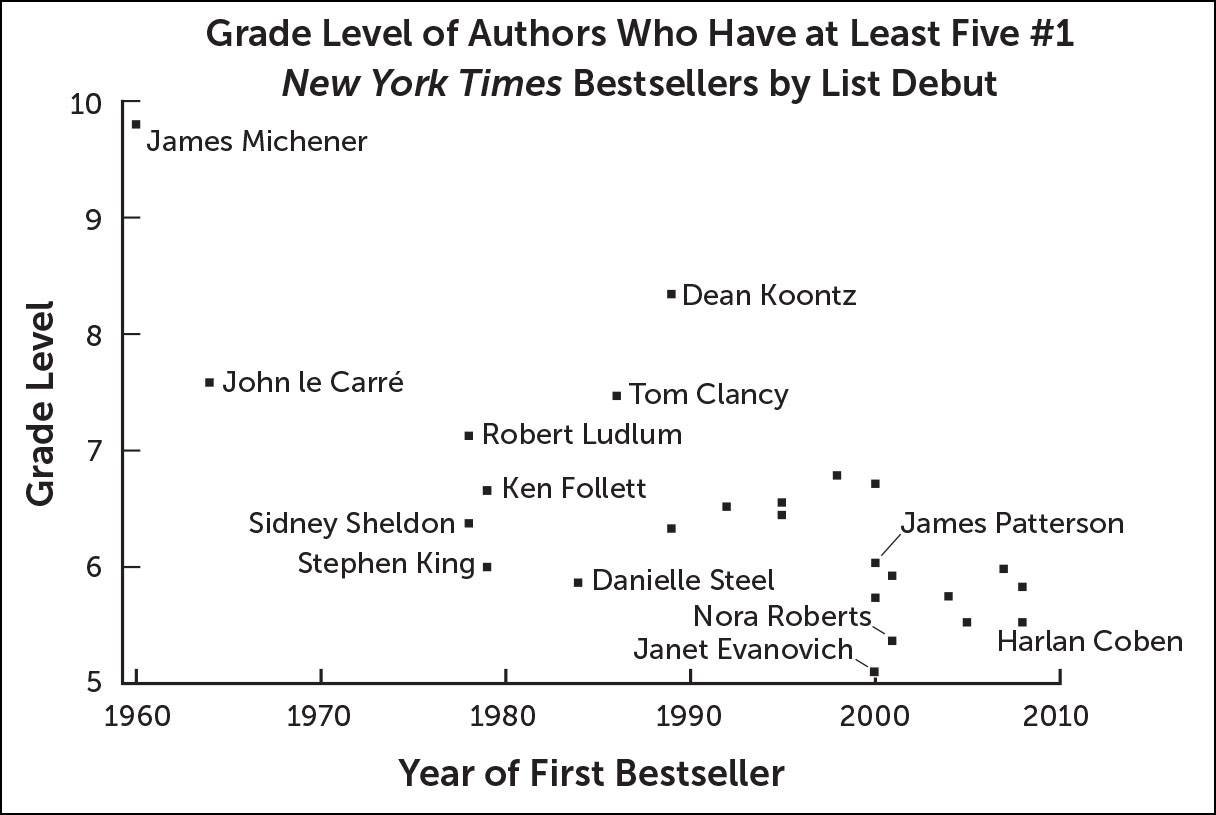

In the following graph I have plotted the 25 authors with the most number one bestsellers since 1960. All of these writers have had at least seven number one hits in their career, and just about all of them are writing for a broad audience: suspense, mystery, romance, action, etc. They are shown by the average reading level of their books and the year in which their first number one bestseller was written.V

Robert Ludlum is known for thrillers like the Bourne Trilogy, which debuted in 1980, but he still wrote at a Flesch-Kincaid reading level of 7.2, not common in popular fiction today. Tom Clancy and Dean Koontz, who both got their starts in the 1980s, write at a level higher than any of the rising popular writers of the last twenty years. Your average John le Carré novel had a reading level higher than 36 of the 37 number one bestsellers from 2014. Danielle Steel ranks as a low outlier for her time period, but she still writes at a higher grade level than many of her even more modern counterparts.

There aren’t just more guilty pleasures representing popular books. The pleasures have gotten guiltier.

Though it is the most prevalent, the Flesch-Kincaid test is just one of many tests of reading level. Most use sentence length as a large component. Today’s bestsellers have much shorter sentences than the bestsellers of the past, a drop of 17 words per sentence in the 1960s to 12 in the 2000s. This means any of these similar tests will show similar declines.

One interesting alternative is the Dale-Chall readability formula. While it too uses sentence length, it has a separate component that factors in the number of “complex” words that appear in a text. In 1948 Edgar Dale and Jeanne Chall compiled a list of 763 words they did not consider complex. From this list it’s possible to count the number of “complex” and the number of “not complex” words in a text.VI The thought is that it’s not just sentence length that can make a book hard to follow for young readers, but the number of words that are unfamiliar.

Since their original list, Dale and Chall have expanded the list to almost 3,000 words. Over 99% of the words in Dr. Seuss’s The Cat in the Hat are considered “not complex.” Seuss’s only two exceptions are thump(s) and plop.

But 1 % complex is unheard-of when it comes to novels. The closest any number one bestseller has come to this is Danielle Steel’s 1993 Star, which uses a record-low 7% “complex” words. The book’s first sentence is below with its one “complex” word bolded.

The birds were already calling to each other in the early morning stillness of the Alexander Valley as the sun rose slowly over the hills, stretching golden fingers into a sky that within moments was almost purple.

On the other side we have Robert Ludlum’s 1984 thriller, The Aquitaine Progression. Twenty-two percent of its words are considered “complex” by Dale and Chall, more than any other number one bestseller. Below are the first three sentences with words considered “complex” in bold.

Geneva. City of sunlight and bright reflections. Of billowing white sails on the lake—sturdy, irregular buildings above, their rippling images on the water below.

Just as we see Flesh-Kincaid scores decline in recent decades, so do the “complex word” counts measured by Dale-Chall. Though the results are much less pronounced than the change in Flesch-Kincaid reading levels, there is a clear downward trend since 1960.

A bestseller once considered typical in complex word usage would now be on the high end of the spectrum. A 2% decrease is small in absolute terms but when you consider the small range a book may fall in, somewhere between 7 and 22%, a 2% fall is significant.

* * *

Where will the bestseller list be in ten or twenty years?

The New York Times bestseller list is looked up to in the book world. It’s prestigious for authors and a guide for readers. By the changes the New York Times has made over the years, it’s clear that they think about its composition. And while their exact methods are undisclosed, they’ve acknowledged that unlike other lists they weigh the sales of certain independent stores more heavily than bigger retailers, tending to give a fighting chance to smaller, more “literary” books versus the commercial, grocery-aisle thrillers. But if the New York Times is conscious of the trend in its bestseller list, they face a question: Should they ever step in to exclude certain authors or genres from the bestseller list for fiction?

It might sound outrageous at first for the Times to try to “shape” the list, but they have done it before. In 2000 a major change was made that excluded the Harry Potter books from the list. In the previous year, the number one spot was filled by a Harry Potter book on twenty separate weeks. The result was a new “Children’s Book” list, which has since splintered even more into distinct “Young Adult,” “Middle Grade,” “Picture,” and “Series” lists.

One obvious fix to the dominance of guilty pleasures would be to split up the fiction list, the marquee list of the New York Times, into one focused on literature and one focused on genre fiction. If the New York Times wanted to promote a diverse range of books, they could make the former list their most touted. A safe haven could at least please those serious readers who want to know what’s popular in the world of books beyond pulp fiction. (Admittedly, the line between genre fiction and literary fiction would be difficult to draw, especially if publishers have a financial interest in gaining a certain categorization.)

A similar effort was already attempted by the New York Times editors. Though it did not alter their main fiction list, in 2007 a “trade” paperback section was unveiled, which was supposed to shine a light on a certain brand of fiction. Here was the description used by the New York Times’s own editors upon its release: “This issue also introduces a new bestseller list, devoted to trade paperback fiction. It gives more emphasis to literary novels and short-story collections. . . .”

The counterpart to the “trade” paperback was the “mass-market” paperback. A book qualifies for the “mass-market” bestseller list based not on its genre or potential audience, but if it’s printed within certain parameters (smaller pages, cheaper paper; often they are those pocket-sized editions you tend to see in grocery stores). And it just so happened that genre paperbacks tended to be printed as mass-market paperbacks. However, the market for these inexpensive books has since shrunk with the rise of ebooks, so more and more genre or commercial books are instead being published in the trade paperback format—that is, as higher quality paperbacks meant to be more lasting. As a result, the trade paperback list has not lived up to its initial selling point. As I wrote this chapter, the number one book on the trade paperback list throughout was the infamous erotica novel Fifty Shades of Grey. It was followed by Fifty Shades Darker and Fifty Shades Freed. All three have been on the list for more than 100 weeks. The rest of the list had some more literary fiction, but also works by authors Gillian Flynn, Nicholas Sparks, and James Patterson, who seem to defy the list’s goal of giving “more emphasis to literary novels.”

If the New York Times wants to accomplish that, they’re going to again need to adjust their categories. Perhaps it’s time to bite the bullet and try to define that elusive “literary” genre rather than base their decisions on the book’s physical format. If they wish to hold on to their cultural perch, they’ll likely need to change again as they have done before.

The broader question that I keep thinking back to, however, is: Should we worry at all about the overall reading level of the fiction bestseller list?

For this question, I say no. I have devoted an entire section to showing how bestsellers have become . . . dumber. It would be easy for me to lump the New York Times reading level decline in with the rise of knee-jerk arguments that the country’s intellect is at an all-time low.

But I don’t think this is fair. Remember, the reading level is supposed to be a rough cutoff for who is excluded from a text. You don’t have to be in sixth grade to read a book written at a sixth-grade level. Books with simpler texts can appeal to a wider audience.

Simple can be great. It includes more people. Writing doesn’t need to be complicated to be considered either powerful or literary. The winner of the 2014 Pulitzer Prize for fiction, The Goldfinch, was also a number one bestseller and has a reasonable reading level of 7.2. While many classics do have high scores (The Age of Innocence at 10.4, Oliver Twist at 10.1, The Satanic Verses at 10.1), just as many have surprisingly low scores. To Kill a Mockingbird has a reading level of 5.9, The Sun Also Rises at 4.2, and The Grapes of Wrath measures down all the way at 4.1. All three of these books are revered by the literary community, but are accessible enough to be taught in high school classrooms across the country.

This inclusion is needed to reach broad audiences. It’s logical that our most popular books are not complex, and I would not expect the future of popular reading to revert back to the lengthy sentences of George Washington’s first State of the Union Address. Kerouac’s most popular book, On the Road, scores at a reading level of 6.6 on the Flesch-Kincaid scale. And while I don’t think Kerouac was referring to sentence structure when he said it, I still think that the following line is worth considering in this discussion: “One day I will find the right words, and they will be simple.”

I. About 15 % of books from the earlier decades are missing from the sample because they are not available in digital form.

II. Up until the creation of radio and television the State of the Union was often a written document sent to Congress.

III. The 2010s only cover 2010–2014.

IV. About 15 % of the books from the first few decades were not available in electronic form and were not included in this analysis. However, even if they all were written at an extremely low level it would not be enough to move the median of these decades below modern levels.

V. The cutoff to make the chart above was seven bestsellers by the end of 2014. There is a possible skew in the data due to the fact that in order for a writer starting to write in the 2000s, he or she had to write much more quickly (and therefore possibly more simply) to achieve seven bestsellers by the end of 2014.

VI. Conjugates of verbs are accounted for. Proper nouns are discounted.